CHAPTER 4

We Shall Go into the Storm of Battle with Brave Hearts

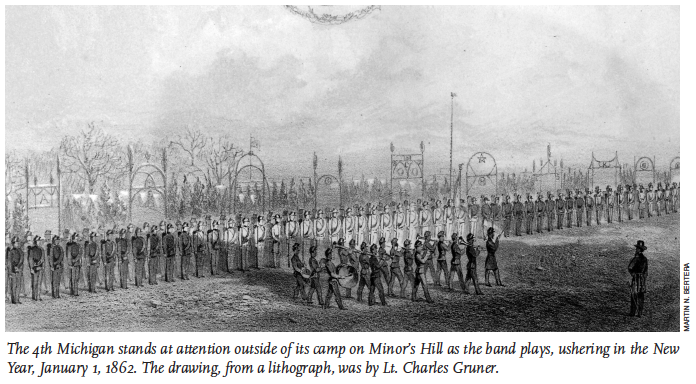

OFFICERS OF THE 4TH MICHIGAN TREATED THE MEN TO A FEAST ON WHAT WAS UNDOUBTEDLY FOR many their first Christmas away from home. Turkey, chicken, and oysters were main dishes, and Silas Sadler of Company G called the meal “Jolly good.” The day was clear and mild, and Sgt. Jonas Richardson said tables were set outside in the streets of the regiment's camp. He and others had been busy “making wreaths, globes, letters and stars to decorate Co. D's street.” The camp was a grand sight to see, for “each company built a large arch over the front of their street.” Henry Seage of Company E also noted the raising of the evergreen arches and that some got into the holiday spirit with drink along with the good food. “Company C tight,” he recorded. “Oysters for Christmas Dinner one Pint to each Man.”

The diary of Sgt. William Limbarker of Company F reflected the homesickness many felt. Though he was allowed to go to Washington on Christmas, where he enjoyed comfortable lodgings and a concert by the Christy Minstrels, he nonetheless wrote that he missed his ex-wife and daughter. “O God don't I wish I would see my famley this winter,” he noted. “I would give all I have to do so.” By now Colonel Woodbury and other regimental commanders had brought their wives into winter camp. “[H]er cheerful and refining presence adds an attractive picture of comfort,” an anonymous officer wrote about Mrs. Woodbury. The effect “takes off the rough edge of campaign life.”

Sadler's parents sent him a box of food that arrived on January 3. “I have been eating Jell[y] and buck wheat cakes ever since,” he wrote. Still, there was duty to attend. “New Years we was out on picket, we watched the old year out and the new year in.” William F. D. McCarty of Company E said it was an eventful duty, with the 4th Michigan's pickets bringing “in thirteen rebel prisoners.” Many officers were allowed leave back to Michigan, but Woodbury and Adjutant Earle remained in camp during the holidays. Both received presents of swords from the officers. Lt. George Monteith, assigned to the division headquarters at nearby Hall's Hill, witnessed the comic mock drill and dress parade put on by the officers and men of the 44th New York for the holiday, calling it “the most ludicrous affair I ever saw.”1

Changes came with the New Year. Major Samuel DeGolyer resigned and left the regiment, reportedly to join the staff of another Union general in the west, though soon he would get authorization from Michigan adjutant general John Robertson to lead a new artillery battery. But there was an unhappier and political subtext. Not only had Colonel Woodbury expressed dissatisfaction with DeGolyer after Bull Run, the major had been arrested before Christmas for allegedly taking lumber from a nearby civilian's cabin. For this he was brought up on charges. “Our Major has Got in to a fix and I think he will be Dismisst from the Armey for snaring lumber[—]they would call it stealing in Michigan[—]and he has been ordered before a board of examiners and it will be a killer on him to leave to go home now,” Sergeant Limbarker wrote.2

What is ironic about his recording of this news is that Limbarker himself had “been out a snairing some doores and window's for a long cabin” a week earlier. But as far as Michigan officials were concerned, DeGolyer, now an abolitionist after his experience as a prisoner, was a heroic leader, and he would prove himself an able artillerist in the Union Army of the Tennessee. In DeGolyer's place, Capt. James H. Cole of Company B, recovered from the wound he received when he'd accidentally shot himself, was the new major. Capt. Charles Doolittle of Company H agreed with Cole's promotion. “A very satisfactory appointment,” he noted. Sergeant Limbarker was even more emphatic in his feelings about the former major: “Sam DeGolier has gone and I am damnd glad of it,” he wrote, “for he was a fool in military maters.” Historians have disagreed. Author Edward Bearss called DeGolyer “one of the best artillery officers” in the Union army during the fighting at Vicksburg.

Another change came in mid-January when Capt. John M. Oliver of Company F, a Monroe man who'd started out as a lieutenant, was commissioned colonel of the new 15th Michigan Infantry Regiment. “He is a good one,” Limbarker wrote of Oliver, “and I am sorry he left this Company for there will be some Damnd fool in his place.” These and other resignations and vacancies triggered a series of promotions and movements between some of the companies' commissioned and noncommissioned officers. Lt. Simon B. Preston, the other officer from Company F who'd been captured at Bull Run, was exchanged and released from Confederate prison late in January, one of at least four 4th Michigan prisoners freed that month. He went home. Others returning to Michigan early in 1862 included Capt. George Lumbard, who recruited for the regiment in Adrian, and Captain Doolittle of Hillsdale. Doolittle had started his service as a lieutenant in Company E, but was promoted late in the summer; he spent several days with his wife and children. “How pleasant to be with those we love,” he noted. The diary of Enoch Davis, the Ohio farmer who'd enlisted with the Indiana men, reflected dramatic changes in the Virginia winter during the early weeks of 1862, when it sometimes turned bitterly cold and snowy. The regiment could be inactive one day because of mud and rain, but busy drilling the next.3

But perhaps the most important change for the 4th Michigan came when new Springfield rifles arrived on January 11, replacing the obsolete muskets, some of which dated back to the 1840s. “It would have done your soul good to have seen the happy faces in our regiment when our rifles were distributed,” Sgt. Eli Starr of Company C wrote; “they are of the Springfield pattern with elevated sights. Our shots [i.e., marksmen] Geo. W. Akers etc. will strike the size of a man's hand with ease at 100 yards. With such guns and such a cause we would be less than men were we to give the Old Peninsula cause to blush…. We are satisfied now, and shall go down into the storm of battle with brave, strong hearts.”4

Sgt. Jonas Richardson of Company D agreed—the rifles were far more accurate than the muskets, and the impact on the men's morale was great. The secessionists, he warned, “had better prepare themselves for the long road.” Corporal Irvin S. Miner, 23, from Hillsdale County, was one of the men who could handle the weapons with some skill. “Shot at target I hit the bulls eye at one hundred yds off hand,” the Company F man noted two days after the new rifles arrived. A few days later, he wrote that he was making even longer shots. “Shot at target off hand at 250 yds. I hit two inches below bulls eye.” In the weeks that followed, Miner would record that he hit targets at greater distances.

Men like Eli Starr were impatient to go on the offensive, but Sergeant Major James Clark, who became a lieutenant in the coming months, wrote that muddy road conditions would prevent them from going anywhere soon, especially with artillery. By now deaths from illness had declined somewhat and occasional mild days graced January and February, but snow and rain predominated. Silas Sadler of Company G said standing with the advance guard on the Leesburg Turnpike was awful on the night of January 23. “Had the worst time on picket we ever Had,” he noted in his diary, “rained and Hailed all the time.”5

Though Sgt. Bill Limbarker's marriage had ended some years previously, his thoughts that winter often were about his ex-wife Harriet. He expressed in his diary his worries and prayers about her and their daughter Eva, who'd been sick with diphtheria. But his more immediate concern as a soldier was that he facing court-martial, charged with providing alcohol to a soldier on guard duty back in November. Typically Limbarker noted the usual camp life details—target practice, picket duty, inspection, and dress parade. One of his more unusual entries that season was when the chaplain, the Reverend Dr. Henry Strong, paid him a visit in order to learn to handle a rifle. “I told him he aught to shoot with spiritual balls in Sted of lead,” the sergeant noted, “but he says they are not so good for Sesesh [secessionists] as lead ones now[.] Bully for him.”

On February 24, a cold day, high winds knocked over a nearby sutler's shanty. Soldiers made the most of the confusion, grabbing items that would have otherwise cost plenty. “My diary records that I had stole a cheese from the sutler,” Albert H. Boies wrote, tongue-in-cheek, nearly 25 years later, “but I think that must have been a mistake.” Boies admitted there were men who remembered that morning and wondered who left a quarter section of cheese outside their tent. Sgt. Orvey Barrett of Company B also profited from the sutler's disaster, snatching two boxes of cigars, some figs, a jackknife, and other items. The angry merchant stalked off to complain to Colonel Woodbury that soldiers were stealing him blind. Of course, the soldiers thought the sutler had been doing the same thing to them for months.6

For some time since their last brigade commander, William Tecumseh Sherman, had been sent west, the 4th Michigan was part of a brigade under Brig. Gen. George W. Morell. The regiment served with the 9th Massachusetts (a Boston-Irish regiment), the 62nd Pennsylvania, and the 14th New York. One soldier in the 9th Massachusetts, Irish-born Timothy Regan, sometimes mentioned the 4th Michigan in his diary.7

Together these regiments comprised the Second Brigade of Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter's division. By early March, President Lincoln ordered the organization of the army into several large corps, so their division was part of the Third Corps commanded by Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman. But pressure was building on Lincoln's administration to show progress in putting down the rebellion. The president demanded action from McClellan, and even common soldiers knew that as the weather improved, they would be on the march. “I expect, Mr. Editor, to date my next [letter] somewhere near Manassas,” Martin Blowers wrote early in March to a newspaper.8

Elements of the Army of the Potomac began to move out a few days later. McClellan planned to advance his forces in a manner that would force the Confederates to abandon their positions and open the road to Richmond, but incur minimal bloodshed. On the morning of March 9, the 4th Michigan was sent several miles to the town of Vienna, a few miles from Fairfax Court House, to guard and work on repairs to the railroad to Alexandria. That same evening, Confederate forces under Gen. Joseph Johnston, who held Manassas and Centreville, gave up their positions and began to withdraw. Early the next morning, the Union army began to move forward.

The 4th Michigan was ordered back from the bivouac at Vienna to Minor's Hill, where the men quickly picked up their gear. Then they marched back out again to rejoin their division, which advanced toward Fairfax. The road was very bad, wrote the regimental correspondent who signed his dispatches “Y,” in “many places the mud was knee deep.” It was a long, weary day, and they halted two or three miles from Fairfax Court House. The men bivouacked in a pine thicket, sleeping on what one soldier called “our couch of boughs” and joined their brigade and division the next morning near Fairfax. “The report is this morning that Centerville is in our hands & also that the rebels are deserting their works at & retreating from Manassas,” wrote Company B's George W. Millens, 22, from Lenawee County. But what caught the attention of reporters was the revelation that abandoned Rebel “cannon” were actually logs painted and propped up to look like artillery. That suggested McClellan had been held fooled, kept in place for months by the mere illusion of Confederate strength. Lincoln responded to this embarrassing news by taking away McClellan's authority as general-in-chief of all Union forces, leaving him in command of just the Army of the Potomac.9

Officers and men who were sympathetic to McClellan believed that taking Confederate positions without loss of life was proof his tactics worked. “[T]he wisdom of McClellan's long delay becomes apparent in that without sacrifice of life or treasure, he now is nearer Richmond than by another path,” wrote Edward Taylor of Company A. For the next few mid-March days, the 4th Michigan remained with its division at Fairfax, drilling and undergoing a review by McClellan. “Provisions are scarce and [prices] very high,” complained the soldier who signed his letters “Y.” Tea cost $5 per pound; coffee, $1.25, while butter was running between 40 and 50 cents and sugar from 30 to 40 cents.

Mistakes continued to cause casualties. On March 12, Pvt. Samuel Tyler of Company H, only about 25, was “accidentally shot through both legs” by a cavalry trooper there at Fairfax. William F. Robinson, by now promoted to lieutenant, wrote that Tyler (whose last name was also given as Taylor) was taken to a hospital in Washington, but he died less than six weeks later, leaving his wife Mary a widow. “[H]e was a fine fellow, well loved by all his mates, and also by all of his Officers,” Robinson wrote. That same day Tyler was shot, McClellan rode by Porter's division, and the men cheered him enthusiastically. While they were aware that Republican leaders weren't happy with their commander, they appreciated McClellan's concern for them. “The men love him as one man & would die for him if necessary,” Millens wrote. More importantly, McClellan now adapted his plans: He would load his men onto ships and sail down the river to Chesapeake Bay, moving the army south to the tip of the Virginia peninsula formed by the York and the James rivers. A large Union stronghold on the coast, called Fortress Monroe, was located here, not far from the town of Hampton. From this secure place, with mountains of supplies and big guns, the Army of the Potomac would advance on Richmond. By divisions and brigades, thousands of Union soldiers were shifted toward Alexandria for the journey.10

The wet, muddy march of the 4th Michigan to the port began on March 15, with the men moving some 14 miles to the town of Cloud's Mill. Here they moved into a comfortable camp of tents equipped with stoves, previously occupied by a New York regiment. Within another day or so, they shifted to a hillside called Camp California within three miles of Alexandria. The town was thronging with thousands of troops, and the loading of so many men onto ships took time. As did many soldiers, a number of 4th Michigan men had thrown away coats, ponchos, rubber gum blankets, and other gear thought to be unnecessary on the long march from Fairfax—the weather had been mild then. But now a cold front blew in, bringing rain and discomfort. Writings of Henry S. Seage of Company E and musician Noah Cressey of Company F reflect their misery, since there weren't enough tents or sufficient shelter. Silas Sadler noted that the men were issued “rations of Bitters”—whiskey—to take their minds off the sodden chill.

After marching all day with heavy packs from Cloud's Mill to Camp California in the rain, Cressey told his brother, the men, soaked, had to try to lie down “and Sleep all Dripping in water.” He called it one of the hardest things he'd ever experienced. The next day Henry Seage wrote that men who tried to leave camp to get out of the weather “were tied up.” Officers tried to keep the men busy with drill. Finally, after delays and standing in the rain and mud for hours, the men boarded the steamer Daniel Webster on March 21. One of a flotilla of transports, it was also the flagship of their division commander, Gen. Fitz John Porter. Colonel Woodbury and his officers considered it an honor to accompany him. The Webster pulled away from the docks and anchored in Chesapeake Bay that night, as did others, waiting for the completion of the boarding of the troops. The next day this fleet of steamers, schooners, and tugboats got underway as ladies on shore waved their handkerchiefs and men cheered.11

The transports moved down the Potomac, sailing by George Washington's historic farm, Mt. Vernon, and old gun emplacements once held by the Confederates. Union gunboats escorted the ships when they reached Chesapeake Bay. “The passage of 25 steamers tugs & schooners down the river & especially their appearance at night exceeds anything in Grandeur I ever beheld,” wrote Lt. George Monteith. Cpl. Charles Phelps of Company D noted that there were “ducks enough to patch Hell a mile” and he enjoyed watching the porpoises “jump up in the water.” But another man in his company, David Webster, about 26, said that “the boys amused themselves a shooting” at those porpoises. Martin Blowers wrote that “a thousand or more passengers made our boat rather crowded for comfort, but the pleasant weather and fine prospects…conspired to keep us in good spirits and make the trip agreeable.”

The flotilla arrived at Fortress Monroe on Sunday, March 23, and the men saw the famous ironclad the Monitor, which earlier in the month battled the Rebel ironclad, the Merrimac (renamed the Virginia by the Confederates). “It is the queerest looking craft that I ever saw,” wrote Sgt. Jonas D. Richardson to his brother. “She is only about two or three feet above, and about ten feet below the surface of the water, being constructed apparently more for service than for ornament.” While many described the ship's turret as “a cheese box,” it reminded Richardson of a revolving tanning vat. The soldiers were also impressed by the big cannon of the massive Fortress Monroe.12

The ships offloaded the thousands of soldiers, and the 4th Michigan with its division marched that afternoon through the burned-out town of Hampton into the country to camp in a clover field. The weather was fine initially but with spring fickleness changed to rain and cold over the next few days as the Union army gathered, probed, and advanced. McClellan prepared to move northwest up the narrow peninsula against the Confederate defenses that blocked the way. This Rebel line stretched from Yorktown on the York River across those few miles of land to the James River. Yorktown, of course, was a historic place, where the Continental Army and allies from the French army and navy forced the British army under Cornwallis to surrender 80 years earlier.

The men of the 4th Michigan shifted their bivouac, standing guard and trying to find things to eat until supply lines were established. Harrison Daniels of Company G remembered that by March 26, the only thing soldiers had left in their haversacks was some coffee—everything else had been eaten and no rations were yet available. “The third day we got desperate and dug muscles [mussels], boiled them and drank some of the broth,” Daniels wrote. Two days later, the regiment was part of a force making an advance toward Confederate positions at the town of Big Bethel. The Confederates pulled back on that hot spring day as Union troops approached up the road from Hampton. “We did not get a chance to see a Rebel, but there has been a large number of them there,” George Millens wrote after returning to camp on March 28. In the heat of that day's march men threw away whatever extra clothing, coats, and blankets they had left, and slaves seeking protection came in large numbers to the Union camps.13

The regiment had a few days of quiet. Edward H.C. “Ned” Taylor, Democrat and McClellan supporter, was convinced the general's approach to the Confederate capital would end the rebellion. “Very soon we will [go] ‘on to Richmond,’ turning their position by moving from east and south…. Success can hardly fail to attend our advance and soon victory will end the war,” he predicted. Two days later McClellan ordered his army to move on Yorktown. The 4th Michigan and its brigade led their division, the troops rising before dawn and marching beyond Big Bethel toward another set of Rebel positions. As the soldiers of Morell's brigade reached Howard's Bridge over the Poquoson River, skirmishers went out and Confederates opened fire from their trenches. According to Morell, General Porter ordered the 4th Michigan to extend the brigade's line of battle to the river. As they did, Union artillery opened up on the Rebels, who fled. It appears that the men of the 4th Michigan might not have fired a shot in their first confrontation with the Confederates on the peninsula, though Henry Seage wrote that they “took two prisoners.”14

Their brigade marched on. As they moved by the abandoned Rebel positions near Howard's Bridge at a place called Cocklestown, the soldiers discovered barrels of peanuts and molasses hidden by the Confederates. Albert H. Boies later wrote some of these treats were hidden in an outhouse, while others simply recorded they were found the barrels in area buildings. Men from the 14th New York were among the troops who joined the Michigan men in the enjoyment of the peanuts and molasses. Boies said the two regiments kidded each other about it afterward. When the Michigan soldiers marched by the 14th New York, someone invariably would call out, “Hello there, who got the peanuts?” New York soldiers yelled back, “Who stole the molasses?” Henry Seage made note of the day's treat in his diary: “Molasses had to suffer.” Their brigade advanced another three miles toward Yorktown, with the 4th Michigan camping that night in the woods.15

Porter's division rose the next morning, April 5, at daybreak, marching into a heavy rainstorm and deep mud. Dr. Chamberlain wrote that the 4th Michigan led this march to Yorktown, which anchored the line of Confederate forts, breastworks, and trenches across the peninsula. “We came in right of the rebel works about ten o'clock in the forenoon,” he wrote. “When we were within about a mile of them, w-h-i-z came a shell over our heads, making most of the men dodge their heads, involuntarily. The next instant all were cheering. The dance was about to open.” The regiment's assignment was to support Capt. Charles Griffin's battery, part of their brigade's artillery, and soon these and other Union guns were firing back from a hill off the road. The Michigan men took positions to the right of the batteries, partially screened from the Rebel gunners by some pine woods and brush. Dr. Chamberlain wrote there were remnants of trenches here, dug back in the American Revolution. The men of the regiment quickly began to improve, extend, and enlarge these old works as the artillery blasted. “Pieces of shell were flying in every direction,” the doctor wrote. Edward Taylor said that Griffin's gunners silenced a battery of three Rebel cannon. “Every shell he [Griffin] threw exploded within their works,” he wrote.

The firing continued for two hours, lulled, and resumed sporadically. Major James Cole cracked a joke when his hat was blown off his head by the impact of an exploding shell. Another soldier felt something smack nearby and fall into his shirt—a small but spent iron ball, canister shot from a Confederate gun, dropping down his collar. He reached back, removed it from this shirt, and dropped it into his pocket, a souvenir of Yorktown. Some men realized there was nothing for them to do until their commanders called on them, so they lay down in their earthworks to rest. Others were so interested in the projectiles fired at them that they jumped out of their trenches and ran to retrieve expended Rebel cannon balls and shells that plunged into the ground without exploding.16

Capt. Charles Doolittle wrote that the Confederate gunners “have the range of our gun pretty well and strike pretty close to our men drawn up in line in [the] rear of Griffin's gun.” Several Union artillerymen were hit and sharpshooters also fired at the Rebel gunners. But for all the lead that was flying, the men of the 4th Michigan escaped injury until sunset, when a private whose name was given as “Joseph W. Thomskins” of Company C was wounded by a shell that exploded near the center of their line. Fragments struck him in the neck, shoulder, head, and groin. These wounds soon ended his service with the regiment. The 4th Michigan went on picket that night, moving quietly forward to what George Millens called “a short distance of their breastworks”—close enough that he could sometimes hear the voices of Confederates. Sharpshooter firing periodically cracked across the fields, and Rebel artillery fired three shots in the darkness toward the Michigan men. Finally they were allowed to bed down with their weapons close at hand. The regiment remained there the next day under sporadic cannon and picket fire. Dr. Chamberlain explained that there'd been talk of storming a nearby Confederate fort during these first days at Yorktown, and there was pride throughout the regiment when an artillery commander said he would choose the 4th Michigan to do the job.17

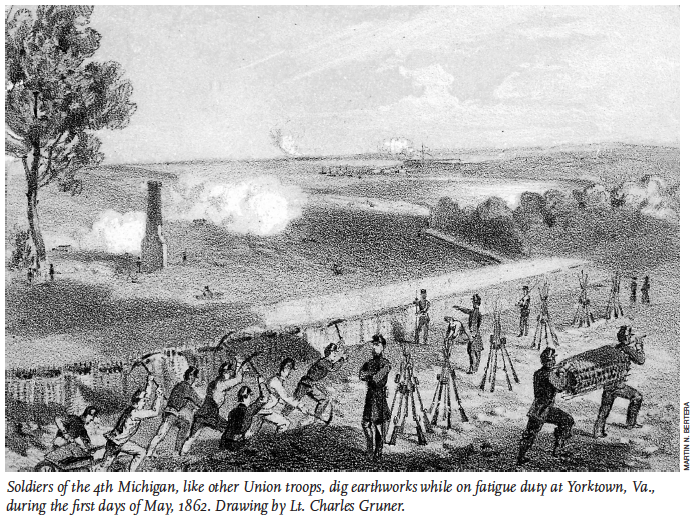

Though the men were convinced a large battle was about to be fought, there would be no storming these Confederate forts. Other than periodically trading picket fire, the soldiers worked, digging and extending trenches. General McClellan didn't order his army to attack; instead he ordered a siege, believing that there were tens of thousands of Confederate troops in the Yorktown defenses. For the next four weeks, the Army of the Potomac dug trenches, built roads, and erected bridges to bring up big guns to blast the Confederates out. The commander of the division of which the 4th Michigan was part, General Fitz John Porter, was McClellan's point man for the siege preparations. The regiment remained on the front with its brigade at Yorktown for the next few days, bivouacking in rain and cold. Most of the soldiers still had no tents. Often exposed to shelling, they came through it with only a couple of minor wounds. They were still short on food, since the army's supply system hadn't quite been finished, and they could build no fires at night. Brigadier General Morell expressed pride in his men for their conduct on April 5 and the way they bore up over the next several days. “They were raw troops, for their first time under fire,” he wrote, “and yet I doubt if their patience and coolness could have been surpassed by veterans.”18

Irvin Miner, who had recorded excellent target shooting in his diary, now put his skill to deadly use. “I was detailed as a sharpshooter to pick off the enemy's gunners. Was shot at five times. I hit one reb at 1100 yds,” he wrote. Early the next morning, April 8, Capt. George Spalding of Company B was wounded in the arm while he was out “on a scout” of the ground between the Union lines and the Rebel works, attempting to determine the number of heavy Confederate guns, but he recovered quickly. That same day, the 4th Michigan got praise from Gen. Samuel Heintzelman when their pickets “rustled” 19 or 20 cattle intended for Rebel sustenance. The cows were grazing near a Confederate fort, and it seems the Rebels inside were distracted when a carriage pulled up and they cheered the visitor. Capt. Charles Doolittle wrote that Lt. John Gordon of Detroit and 20 men drove off the cattle, “laying out 2 of the rebels” in the process. “It was handsomely done,” the general noted approvingly.

Their brigade was pulled back the next day, shifting about a mile to the right, or east, to camp with Porter's division in a peach orchard on an old farm near the York River. The soldiers again went to work digging new trenches. Henry Seage of Company E wrote that a Confederate sharpshooter fired at the men from a hiding place high in a chimney of a burned-out house at the time, but the brigade's artillery commander, Charles Griffin, brought out a gun “and soon made a ruin of the chimney, reb and all.” The weather continued fair and foul, but at last new tents arrived.19

A new routine was soon established as big Union guns were brought up and thousands more soldiers arrived. The men of the 4th Michigan, like other troops, would leave their camp to stand picket, sometimes at night in the shrinking no man's land between the lines. Or they went on fatigue details, working on roads, gun emplacements, and earthworks. Of course, some soldiers have always tried to get out of work, and Dr. Chamberlain remembered an Indiana man named Orville Carver as notable in this regard. In order to dodge fatigue, Carver tied a piece of bandage around one of his toes to indicate he'd been injured. This worked for a while, since officers and the assistant surgeon himself assumed a man with a bandaged foot was unable to work. Unfortunately for Carver, it soon dawned on Dr. Chamberlain that he didn't remember bandaging the soldier's foot, so he asked to see Carver's “injured” toe. Of course, Carver was soon back digging trenches. But the weather improved and men could sometimes hunt for oysters down on the York River when they were off duty, or they could buy them from local residents. Once there was an established work-and-picket routine, officers quickly resumed inspections, drill, and dress parades.20

But the artillery roared as gunners dueled, sometimes trading shots at night, and squads of soldiers clashed in the darkness as they conducted reconnaissance between the lines. The men saw Union gunboats firing their cannon from the York River. On the night of April 17 came heavy firing from the Rebel entrenchments and forts. “Firing all night, on guard, hott as thunder,” Enoch Davis noted. A history of the 5th New York states that the 4th Michigan “took three hundred prisoners” that night when Confederates came out of their forts to attack the new Yankee trenches, but military records and reports and soldiers' accounts make no mention of such a significant capture by Woodbury's men—only sharp skirmishing. His regiment came through these scraps with barely a scratch.

But that kind of luck could not hold. Captain Abram R. Wood of Company C, about 35, had been sick when the Union army shipped out from Alexandria, but he improved and joined his regiment in mid-April. Wood became the regiment's first fatality at Yorktown when he walked out beyond his picket line on the night of April 18 and was shot by a soldier about 22 years old from his own company. That soldier—an odd fellow named Luke Barnes who didn't fit in well with others, according to family letters—thought Wood was a Confederate. “In posting pickets Friday evening he passed outside of our lines a few rods and was shot by one of his own men,” Martin Blowers wrote of Wood, who had a wife and children back home. “He survived but a few hours.” George W. Owen of Company A wrote that before Wood died, he stressed that his wounding was not the picket's fault. This case of mistaken identity was the regiment's only fatality at Yorktown. In the wake of Wood's death Lt. Harrison H. Jeffords was promoted to take his place. Luke Barnes may have paid an emotional price for his mistake, as his words would seem to indicate in the months ahead. Another member who suffered a terrible blow that month was the chaplain, the Reverend Henry Strong; he was notified that two of his children had died back at home.21

Though the morale of the regiment was high, an exception was Dr. William E. Clark, the surgeon. Clark was angry about his treatment by Colonel Woodbury, and he let Governor Austin Blair know it. “On reaching the regt. every obstacle was thrown in my way as my assuming my duties,” Clark complained. The problem appears to have been one of politics as well as personality, for Clark, like the governor, was an abolitionist and Republican, while Woodbury was a War Democrat. “I have been aware that his [Woodbury's] influence was against me from the first,” Clark complained. He had confronted Woodbury, but the colonel replied that he was satisfied with Clark as doctor and surgeon. But this didn't end the matter, and Clark and his brother Joseph B. Clark of Dowagiac, charged in subsequent letters that Woodbury spoke insultingly of Republicans and hoped to pressure Dr. Clark to resign. As a result, Clark wanted the governor to place him in another Michigan regiment. He would eventually get his wish, though he would prove to be even more unpopular there.

Was Dr. Clark treated as badly as he claimed? Had there been a kind of conspiracy among Democratic officers to make things difficult for him? Albert H. Boies, then a high-spirited teenager from Hudson, wrote years later that Dr. David Chamberlain suggested to Clark that he needed a helper to do chores. Chamberlain recommended Boies. In the three months Boies had the job, he drove Dr. Clark to distraction and cursing. Boies failed to salute the doctor when he was in the presence of a general. Asked by Clark to see if a pot of clean water was hot, Boies stuck his finger in it to check. Boies admitted that he and his friend Fred Duryee, Dr. Chamberlain's young assistant, enjoyed aggravating the high-strung Dr. Clark. “Fred and I practiced some amusing things upon the surgeon, who by the way, was very eccentric and absent-minded,” Boies wrote.22

The weather turned rainy. Nights were still sometimes very cold, while days could be hot and humid. Several men of the 4th Michigan had close calls as they dug rifle pits within range of the Confederate guns, sometimes directly in front of their forts, as soldiers extended trenches and roads for the artillery. Lt. William F. Robinson of Company H wrote his parents that “our boys look up and laugh and sing out ‘put him in the Guard House’ every time a shell bursts over their heads.” On the morning of April 29, shells dropped in among soldiers “working in full view of the enemies fortification distant about one half mile,” wrote George Millens. “The rebels threw shells at us all the forenoon striking the dirt & burying themselves in the sand & then explode [—] one shell cut a mans shovel handle off.” The Confederates were excellent shots, he noted, but none of them were injured. Edward Taylor said that the Rebel shells were so unreliable that Union soldiers generally had only to worry about being physically struck by the projectiles.

April turned to May and the rate of Confederate shelling increased. Officers like Lieutenant Robinson believed that the battle for Yorktown would soon begin, with the Union army having to fight as many as 100,000 Rebel defenders they believed were inside. “It will take some hard fighting to take the Rebel forts,” wrote Silas Sadler. “They are pretty strongly fortified but God will be with the right…. I am in hopes God will spare me through the great battle that is so close at hand.”23

There were nothing like those huge numbers of Confederate troops at Yorktown. When the Union army arrived in early April there had only been about 11,000 Rebel troops present, and they had been reinforced over the weeks that followed. But as McClellan prepared to open fire with his masses of artillery a month later, the Confederate commander, Gen. Joseph Johnston, ordered his men to evacuate their positions, covering the withdrawal to the northwest with the artillery bombardment that began on May 1.

As this shelling continued, Col. Dwight Woodbury made up his mind to confront Gov. Austin Blair about a subject that was very important to him—promotion. Woodbury started by saying he was surprised that a couple of officers in other outfits had been promoted to colonel. He had some very good officers in his regiment; why had they not been considered? Then Woodbury pointed out that he was Michigan's most senior colonel—he had served for a year and run a good regiment. Yet there was no sign he was going to be promoted to brigadier general.

Of course, Woodbury needed Blair to approve of such a promotion because the War Department consulted with important state politicians on the question of generalships. These weren't just matters of military leadership and experience, they were also matters of politics. Woodbury believed he had the support of Michigan's congressional delegation, yet no promotion had come. That had to mean that Blair wasn't interested in seeing him become a general, and Woodbury wanted to know why. How Blair answered Woodbury is unknown—office copies of the governor's outgoing correspondence were destroyed by a fire in later decades—but Woodbury never got his brigadier general's star.24

The Confederate artillery kept firing into the early morning hours of May 4—and suddenly stopped. Sergeants Jonas Richardson and Irvin Miner were assigned to a detail digging trenches near Rebel positions that morning when the Union soldiers realized the Confederates were gone. “Was detailed to work on outer parallel, but came back to camp after visiting deserted fortifications,” Miner noted. “Yorktown evacuated.” Richardson was leading a fatigue duty detail to Union forts numbered 10, 12, and 13 when the discovery was made. “The firing had been so incessant during the night that we were expecting considerable hindrance,” he wrote, “but what was our surprise when upon clearing the breastwork to find our Pickets and sharpshooters almost under the shade of the Rebel fortifications at Yorktown. Soon one or more are seen to climb the walls and for [a] moment strain his eyes in all directions to see if it were possible to catch a glimpse of the enemy, but no, all is gone.” Pvt. Blowers of Company F wrote that “there was much rejoicing among the troops” over what he and others called “a bloodless victory.” Elements of the Union army moved out in pursuit, but Porter's division remained at Yorktown. Later they heard cannonading in the distance.

There was still danger at Yorktown, for the Confederates had left land mines or booby traps called “torpedoes,” made of artillery shells, planted around the works. As a sergeant and some men from another regiment were walking to Yorktown's fort, Charles Phelps wrote, “one of them struck something attached [to] or stept on one of those torpedoes which you have heard of.” The device exploded, “wounding 5 or 6 pretty bad,” he wrote. Dr. Chamberlain treated the wounded men.25

There was fierce fighting the next day near Williamsburg, where Confederates under Gen. James Longstreet fought a rearguard action against the pursuing Union troops, but the 4th Michigan remained with its division and others at Yorktown for another three days. On the night of May 7 the regiment packed and marched to Yorktown to spend the night in the abandoned works. The next day around noon they headed to the town's wharf, boarding the steamer Vanderbilt. The ship headed up the York River with other transports about 25 miles through the moonlit night to the town of West Point, Virginia.

The next day, May 9, the soldiers climbed into pontoon boats that took them ashore, where they camped on the grounds of a plantation. Here their division joined that portion of the Union army that had gone after the Rebels from Yorktown. The Michigan men watched the burial of troops who'd been killed in the fighting and witnessed the hanging of a black man accused of cutting the throats of wounded soldiers who hadn't been able to protect themselves. They cheered when General McClellan rode by their camp on May 11 but remained near West Point for two more days, when the next phase of McClellan's advance on Richmond began. The Union army rose before dawn, and having been issued three days' worth of rations per soldier, slowly got started as brigade after brigade moved out, wagons and caissons rattling along. The men of the 4th Michigan tramped on in the rising heat, some men falling out from exhaustion. The dusty road to the west took them through woods, and they covered 12 miles or more before stopping to bivouac in a field at Cumberland. Capt. Charles Doolittle complained that they had taken a wrong road that day and so had marched additional miles because of the error.26

Stopping, starting, waiting, and marching in rain and mud and heat, the regiment and thousands of other soldiers slowly moved over the next four days. On May 16 they marched only five miles on the muddy road, stopping that night at a place called White House Landing on the Pamunkey River. They camped in a clover field for two days, and here the men of the 4th Michigan learned on the 18th they were now part of a new army corps that had been created by General McClellan. This was the Fifth Corps, and it was commanded Gen. Fitz John Porter. In Porter's place, Brig. Gen. George W. Morell was put in charge of their division. Col. James McQuade of the 14th New York would command their brigade. Thus the regiment was part of the Second Brigade, First Division, Fifth Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

As the lead elements of the army reached the Chickahominy River, Confederate troops pulled back to the edge of Richmond, destroying area bridges. The Chickahominy, running from the northwest to the southeast, provided a natural obstacle to McClellan's men. In the days that followed, the army moved up for what soldiers assumed was going to be the siege of the Rebel capital. On May 19 the 4th Michigan slowly moved out from White House Landing with its brigade in rain and mud, marching several miles and reaching Turnstall's Station on the Richmond & York River Railroad.27

Again the brigade of which the 4th Michigan was part alternately marched, stopped, and waited as the army pulled itself along like a giant caterpillar. The soldiers were in camp one hot day, moved a few miles the next, and then were sent out, briefly, without their knapsacks on a march that seemed to promise a brush with the enemy. But this movement on May 22 was ordered to a quick halt. The men went back for their packs and continued on, marching about six more miles in a hard rain. The Confederate capital was only several miles away to the west. “We are now within twenty miles of Richmond,” wrote George W. Owen of Company A, “and will probably be in Richmond before next Saturday night.”28

They camped in a field surrounded by woods that night, not far from the town of Old Cold Harbor, a few miles east of the Chickahominy. They remained in their bivouac the next day and heard gunfire ahead, where Union columns were pushing on. But for the Michigan regiment the officers ordered a dress parade, and one soldier from Company B, Homer E. Fisher, an Indiana man, was court-martialed for fighting with Major Cole while they'd been on the march. Colonel Woodbury, who lived for a time in Ohio when he was a young man, was believed by some be the writer of a letter back to a small-town newspaper, using the pseudonym “Volunteer.” Volunteer confidently predicted that the men of the Union army “soon expect to be in the capital of the Bogus Government.” The writer mocked the Confederate generals for hurrying their forces back to Richmond from Williamsburg, rather than fighting. “[I]t is the wish of all the officers and men that they would make a stand,” he wrote, “for we feel confident that we could soon close the rebellion if the only give us fight.”29

The 4th Michigan's first real clash with the enemy was coming on May 24. Their mission was a simple reconnaissance, and the clash would be considered a skirmish, but it gained them national attention and praise.

As the Union army reached the Chickahominy, its left wing, on the south, was able to cross the river to the side where Richmond lay a short distance away. But further north, the right wing of McClellan's force, including the Fifth Corps, almost due east of Richmond, hadn't crossed. The general's staff needed information about the disposition of the Rebels and needed to know where crossings could be made. As the 4th Michigan bivouacked near Cold Harbor on May 23, a group of engineers and officers, aides to McClellan and other commanders, were sent to investigate. One, a young cavalry lieutenant who lived in Michigan, was George Armstrong Custer. The Chickahominy was 40 or 50 feet wide and swollen with rain, but Custer successfully waded the river.

Now he was ordered to make another reconnaissance, further upstream to the northwest. This time, it was a reconnaissance in force. Custer would go accompanied by the 4th Michigan and a squadron of U.S. Army cavalry. On the rainy morning of May 24, the regiment awoke before dawn and soon marched on the main road that led from Cold Harbor to a Chickahominy crossing called New Bridge. This was one of the structures that had been destroyed by the Confederates. Hiram B. Fountain, a private from Company F who had enlisted from Hudson a year earlier at age 19, wrote that they were only to take their rifles and canteens. After moving about two miles from camp, the column stopped when they reached a house being used as General Porter's headquarters, and there Colonel Woodbury received his orders. The men thought they were going on picket duty, perhaps to work on the damaged bridges or fix roads, Fountain said.30

But instead of marching directly to the river, the men of the 4th Michigan turned off to the right, or northwest, moving on a road through the woods past the last Union pickets. The men left the road, moving into the trees that bordered the river. As they reached an opening in these woods—Sgt. Jonas D. Richardson described it as a wheat field—some of them saw Confederate pickets across the river, leaving open ground and disappearing into the trees.

By now the regiment had marched about a half-mile up the Chickahominy from New Bridge, the place where Lieutenant Custer decided the first troops would ford. He led the way, with Colonel Woodbury sending some 30 men from Company A with him. Many of these men were from Monroe and they recognized Custer as a neighbor. “Why, that's Armstrong Custer,” said one of the soldiers. “Hello, Autie,” said another. But there was no time for socializing. These soldiers, the First Platoon of Company A, were led by Capt. A. Morell Rose, 30. They emerged from the woods, waded into the water, and according to Colonel Woodbury, “crossed without difficulty at double-quick.”

Rain was still falling. The skirmishers, now on the Richmond side of the river, found no enemy infantry, though they saw some Rebel cavalry pickets on a hill in the distance. The First Platoon from Company A formed a line perpendicular to the Chickahominy and advanced through the woods, moving toward New Bridge. The other part of the company, Second Platoon, stayed on the opposite riverbank, moving in concert with their comrades and acting as a reserve. The rest of Woodbury's men stayed a short distance behind in the woods, marching on a parallel course back down the river on the Union-held side. For some minutes, the First Platoon skirmishers went undetected on the Rebel side of the Chickahominy.31

“The skirmishers approached within about 400 yards of the bridge,” Woodbury reported, “when they came upon the camp of the enemy, who were apparently unaware of our presence, being gathered in squads through the camp.” This was the bivouac of the 5th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, detailed to guard New Bridge. Part of a brigade under Brig. Gen. Paul J. Semmes, these Louisianans had three companies out on picket that morning, yet none detected the approach of the 4th Michigan. Now two of these companies were stunned to hear gunfire and look up to see Union troops—the 30 men from the regiment's Company A—firing at them from the woods.

Lt. Nicolas Bowen, a U.S. Army topographical engineer and one of the officers leading the reconnaissance, described that meeting tersely: “[W]e found the enemy and charged them.” He also said that Custer was “the first to open fire upon the enemy.” But though the Louisiana men were initially stunned and dropped back, their officers quickly reformed them and brought up their reserves. Another Confederate company on picket a fraction of a mile away hurried to the scene. In short order the Confederates came right back, engaging the 4th Michigan skirmishers. Woodbury, like some of the other officers, was on horseback, though Lt. William F. Robinson said the colonel got as wet as any of the men when he forded the Chickahominy. As the firing increased, the colonel committed more men to the fight, and it was Custer who rode back across the river to get them.

At the sound of the opening gunfire, Company A's Second Platoon, under Lt. William C. Brown of Monroe, broke into a run along the edge of the river toward New Bridge, where strong Rebel pickets were posted. Brown's men opened fire on them. When the rest of the regiment heard the skirmish fire, the officers halted and formed a line of battle in the woods at the river's edge. “[We] loaded our guns, fixed bayonets and were ready for the contest,” wrote Leister T. Scholfield, a 23-year-old soldier in Company H.32

Company B was ordered forward to cross the river, keeping to the left, toward New Bridge, while two other companies were sent across to the right to aid Company A's First Platoon. There are conflicting suggestions that these first reinforcing companies on the right were G and K or F and D; Jonas Richardson said they were Companies C, D, F, and I. Whatever the order of their arrival on the southern side, the men from Company B, wading the Chickahominy near the wrecked bridge, were most exposed to musketry of Confederate pickets. Richardson said the men gave a tremendous shout as they ran out of the woods into the river. “Our men crossed under a severe fire, the water in places being up to their armpits, obliging them to take off their cartridge boxes and hold them above their heads,” reported Lieutenant Bowen, the engineer, whose horse was shot from underneath him. Irvin S. Miner of Company F wrote that “we plunged waist deep in water with a shower of lead in our faces.” Charles W. Phelps of Company D noted the crossing was made in a hard rain and confirmed that the water was so deep in places that men had to swim, even while trying to keep their ammunition dry.

But the first three companies made it across to join Company A's First Platoon skirmishers, slogging out of the river into the belt of woods where their comrades were trading fire with the Confederates at their encampment. A short distance to the southeast, Company B reached the trees to establish the left of the Michigan line. Abel M. D. Piper, 25, a big man from Lenawee County nicknamed “Elephant,” was killed and several others were wounded, Cpl. George W. Millens wrote. But the company, under Capt. George Spalding, kept up a steady fire. Along with the other Michigan soldiers who had crossed, they pushed the Louisianans back by reason of their superior rifles and protection in the trees. Orvey Barrett wrote that Custer cheered them, shouting, “Go in, Wolverines, give them hell!”

They did. “The enemy on the opposite side of the river cooperating with their forces on our flank, effected a crossing and drove our troops back about 400 yards,” Col. T. G. Hunt of the 5th Louisiana wrote. By now the 4th Michigan had four companies across the Chickahominy in a line of battle. “The fight continued from behind trees for a while in which the Rebels got far the worst of it, for our shots told every time,” George Millens bragged.33

Not only had these 4th Michigan companies established a strong line, they also cut off some of the Confederates and made them prisoners. Captain Spalding, whose left arm was still in a sling from his wound at Yorktown, said later that a Confederate officer indicated he was surrendering. But only 10 feet away from Spalding, the Rebel raised his musket and fired. The bullet ripped away the captain's pistol belt, causing him pain, but no serious injury. One of the heroes of the action in this vicinity, it was claimed, was Homer Fisher of Company B, who had been arrested and court-martialed in a “drumhead” trial the night before for his fight with Major Cole. Fisher begged his officers not to be left behind that morning, so he was allowed to go with his company. But he got separated from them as they forded the river, and he emerged from the water closer to New Bridge. Alone, he came across a five Rebels in the woods, reportedly “destroying” their picket post, according to an account published later, by killing, wounding, and capturing the lot. For his actions, Fisher's court-martial was commuted.34

At the skirmish line, Woodbury would write, the Louisianans were reinforced by two additional regiments, though Confederate reports state that the 5th Louisiana was in fact bolstered by three companies of the 10th Georgia Infantry. The Georgians advanced, but their smooth-bore muskets didn't have the range of the Union rifles; three of them immediately fell wounded. Colonel Hunt ordered his men to charge, and he claimed in his report this action forced the Union troops to pull back across the Chickahominy. Other accounts say the Confederate attack was repulsed and that the Georgians and Louisianans retreated to a safe distance, hundreds of yards away in the brush-covered ground. Pushing up from the woods along the river, the Michigan soldiers formed along an old fence that rose above a drainage ditch or channel from the river to a nearby field. The 4th Michigan's side of this fence, the ditch, was a swampy mess, though it provided some cover. Here, Leister Scholfield wrote, “we fought hard for two hours, in mud and water up to our waists.” Some soldiers stood in shallower sections. “The water was knee deep in this,” wrote Charles Phelps, “and right on the back was a fence which made a good breast work.”

The clash now reached its climax. Woodbury ordered most of the rest of his men across, leaving only one company on the northern side of the river as a reserve. Millens claimed that some Rebels on the other side “began to run & we all plunged in.” The accounts of soldiers and officers from the regiment indicate companies like H and D crossed the river late in the skirmish. “We commenced firing on them at this [ditch]” Phelps wrote; “the reg't all came across and opened on them[.] we kept up for about half an hour when the rebels run like the devil.” The 4th Michigan had been on its own in this day's fighting—the squadron of U.S. cavalry troopers, for whatever reason, did not ford the river and join in. But at last the Rebels brought up an artillery piece and opened fire on the Michigan men. This was probably the point at which the regiment withdrew across the Chickahominy.35

“The enemy, strongly re-enforced, advanced upon us, but we held him in check till our ammunition gave out,” Lieutenant Bowen reported. There was no reason to stay any longer. The soldiers of the 4th Michigan were running out of cartridges and they had shown infantry could ford the rain-swollen river. Woodbury said his regiment withdrew in good order, removing their wounded and 10 or 12 of the wounded Confederates. “We took some 37 prisoners, including 1 officer,” he reported. The 4th Michigan's officers believed they had killed 100 or more of the enemy, though a more conservative count by Confederate officers put their dead at 18 with another 26 men wounded and 34 or more missing. Rebel fatalities may have been higher than this; John Bancroft noted that 4th Michigan men found the bodies of eight more Confederate soldiers in the Chickahominy in that same vicinity three weeks later. That could mean that at least 26 Confederates were killed in the New Bridge skirmish.

Back on the north side of the Chickahominy, one of the Confederate prisoners spoke to Woodbury now that the clash was over. “I might have shot you half a dozen times,” the Rebel claimed.

“Why didn't you?” Woodbury asked.

“I took you for some damned common orderly,” the prisoner answered. If the colonel or any of the officers or men who heard that explanation laughed out loud, the record does not show it. News accounts and men's letters said that McClellan and Porter personally congratulated Woodbury and his regiment. Lieutenant Bowen, who reported on the mission to his superiors, was also impressed. “Too much praise cannot be given to Colonel Woodbury and his command,” he wrote. Writing back to an Ohio newspaper, Woodbury called the skirmish “a brilliant affair for us.”36

Incredibly, for all the gunfire exchanged, only two of the 4th Michigan's men had lost their lives at New Bridge. In addition to Pvt. Piper, a Lenawee County man, Franklin Drake, 20, of Company B was mortally wounded and died a short time later. Several more men were injured less severely. The mission had only been a reconnaissance and, as far as history was concerned, a mere skirmish. But it brought the name of George Custer to the attention of the press and the commanders of the Union army. “Lieut. Custer deserves praise for his coolness and bravery,” wrote a member of Company A. “It will do his friends in Monroe good to hear that he is already making his mark so soon after graduating [from West Point].”

This had been the 4th Michigan's first real fight as a regiment. They had pushed into Confederate-held ground, thrown the defenders back, and held their position with discipline. They had withdrawn in good order. Colonel Woodbury was proud of his regiment, and so were Generals McClellan and Porter. McClellan himself would transmit the news of their success on to President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. “The conduct of my own officers was, without exception, faultless, and both officers and men gave conclusive evidence of their coolness under fire,” Woodbury wrote.

General Porter warmly congratulated Lt. Col. Jonathan Childs as he turned his prisoners over for questioning that day, shaking Childs's hand. “The 4th Michigan is covered in glory,” Porter said proudly. “Covered with mud and water, too,” Childs joked.

Perhaps the only discouraging word about the skirmish seemed to have come from the brother of Dr. William Clark, the regiment's unhappy surgeon—and this was aimed squarely at Woodbury. Dr. Clark had gone across the river with the men of the 4th Michigan that day and had received kudos in the press for treating wounded men while under fire. Clark's brother, Joseph, claimed in a letter to Governor Blair that Woodbury hadn't really crossed the Chickahominy with the men who did the fighting, but was taking credit for having done so. Given the other statements that place the colonel with the skirmishers, this criticism of Woodbury cannot be taken seriously.37

For the other officers and men of the regiment, New Bridge was a great victory. Henry Seage of Company E, 17, recorded the skirmish in his journal in the typical brief style of a young Civil War diarist, but his pride was obvious in the last sentence of his entry for Saturday, May 24: “McClellan met us & said Boys you done nobly today.”38