2 British Columbia and Canada Take Root

The heart of the slow but steady expansion of BC’s emerging capitalism in the last half of the nineteenth century lay in the bounteous coalfields of Vancouver Island. And nowhere was working-class conflict more evident. From the beginning, the Island’s miners waged a continuous, uphill battle for better wages, an end to hazardous working conditions and the simple right to join a union. Although their many strikes failed to achieve all their goals, the coal miners’ tenacity passed on to future generations of industrial workers in BC a stout tradition of fighting hard to win the wages and workplace conditions they deserved.

The seeds of struggle had been sown at the Island’s very first coal-mining operation at Fort Rupert in 1850, when the small group of miners hired from Scotland, aghast at conditions, downed their tools and refused to work. Two were clapped in irons for breaking their contract. Barely a year into its operation, the mine had already seen the province’s first strike and the first punishment of workers for standing up for their rights.

Conditions in the early Vancouver Island mines were brutal, made worse by the paltry pay. Strikes occurred in 1861 (short), 1865–66 (six months) and 1870–71 (five months). The second dispute was a harbinger of things to come. For the first time, Chinese workers, many of them refugees from the end of the gold rush, were hired as strikebreakers. With the strike broken, they were kept on. Initially, the Chinese were paid the same wages as white miners. That didn’t last long. Ordering their pay cut in half, the mine’s general manager James Nicol explained, “If we are to pay the Chinaman the same rate of wage as the white men, there will be no use employing them.” After that, the Chinese presence was consistently opposed by most white workers; almost all subsequent strikes featured a demand to ban Chinese workers from the mines.

Meanwhile, Lady Luck smiled for good on the determined Robert Dunsmuir. On one of his regular prospecting forays in 1869, he stumbled over a large tree root. When he took a second look, he saw that the root was laced with coal. The ambitious Scotsman had discovered the famous Wellington Seam that made his fortune. The instant coal-mining community of Wellington was soon BC’s first company town. Small family homes, boarding houses for single miners and the general store were all built and owned by Dunsmuir, Diggle and Company. “A capitalist is one who lives on less than he earns,” Dunsmuir liked to boast and in his case, what he earned was immense. He soon built a fine house for himself and his large family overlooking Nanaimo.

Conflict between the miners below, many of whom brought their British working-class sensibility with them, and their master on the hill was rarely absent. An attempt to resist a pay cut fizzled out in 1876, but the next year the miners had a union, the Coal-miners’ Mutual Protective Society, the second such miners’ organization in Canada. This time, they took on Dunsmuir for real. When the mine owner rejected demands that their old rates be restored and the company fix a faulty scale, they walked off the job.

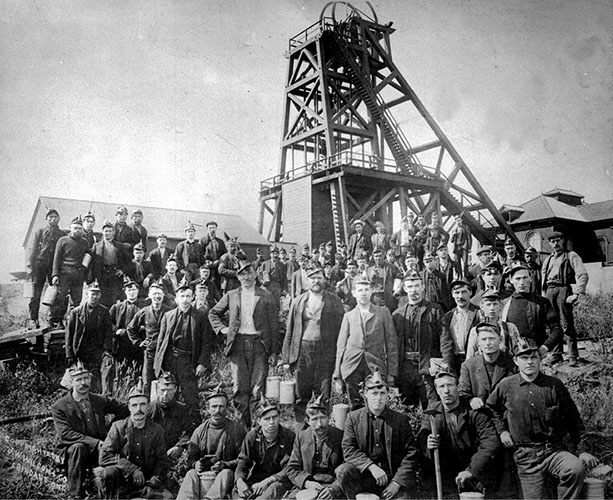

Nanaimo coal miners gather at the pithead of one of the area’s first mines in the early 1870s.

Image B-03624, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

It was Dunsmuir’s first serious labour dispute, and he responded with what became his standard hard-line response. Striking miners were ordered out of their company-owned homes, strikebreakers were brought in to keep the mine running and Dunsmuir served notice that anyone who dared strike against him would never be rehired. When the resolute miners began giving strikebreakers a difficult time, Dunsmuir added a fourth plank to his strike strategy, convincing the government to send in the militia. This early alliance between capital and the state to impede BC workers from asserting their rights set the tone for industrial relations in the province for years to come.

Shocked to learn of the death toll among Chinese labourers helping to build the Canadian Pacific Railway, recent Chinese immigrant Linglei Lu commemorated their toil in a series of oil paintings to mark Canada’s 150th anniversary. “I want people to remember not only the founding fathers but also the contribution of common labourers, especially the Chinese workers,” he explained. “They are all Canadian heroes.”

Linglei Lu, Great Iron Road, 2016, canvas oil painting 91.4 x 121.9 cm, courtesy of the artist.

In response, the miners had their courage, solidarity and a relentless quest for decent wages, safe mines and the right to join a union. They also had the active support of their wives and daughters. When a group of newly hired strikebreakers showed up during the 1877 strike, women gathered at the pithead, children clutching their skirts, and shouted, “Have you come to take the bread and butter out of our mouths?” When the militia first attempted to force miner families out of their homes, one cadet was thrown off a bridge while others were kicked and punched by a line of women as they passed by. But with dwindling resources and the mine still producing coal, the miners could not hold out forever. After four stubborn months, they called off their strike, managing to at least secure proper regulation over the scale that weighed their coal production for payment.

Not surprisingly, no one relished the chance to hire Chinese workers for abysmal wages and use them to maintain production during strikes more than Robert Dunsmuir. By 1878 a third of his 240 miners were Chinese, often working underground as runners who pushed empty coal cars to the rock face. Testifying before a Royal Commission on Chinese immigration, Dunsmuir praised their work habits and willingness to take on unappetizing tasks shunned by whites. Their low wages were also attractive to the mining magnate. Mine owners would be unable to compete in the coal marketplace if Chinese workers were not available “at much smaller pay,” Robert Dunsmuir told the commission. “I consider their presence beneficial to the progress and development of the country.”

By 1881 there were 4,350 Chinese immigrants in British Columbia. They hailed from a handful of counties bordering the city of Canton in southern China. Desperate poverty, overpopulation and a series of violent uprisings drove them to try their luck abroad, willing to pay agents hefty sums for the passage. Almost all were men. Thousands more arrived to work on the massive project that, like the gold rush, was to fundamentally change the BC economy. A key to BC joining Confederation, construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway galvanized the province, facilitating access to markets across Canada and establishing its terminus, Vancouver, as a major port for exports.

But first it had to be built. With towering cliffs plunging straight to the raging river below, no section, not even Rogers Pass, was more difficult and costly than the route through the Fraser Canyon. The major contractor, an American by the name of Andrew Onderdonk, said the railway could not be built through the canyon at an affordable cost without hiring Chinese labourers at a dollar a day. Dubbed “thundering grasshoppers” by white workers earning at least twice the wages, an estimated seventeen thousand Chinese immigrants worked at various times on the railroad.

Their heroic labour, under conditions that could hardly have been worse, was a major contribution to Canadian history. Working in gangs of thirty and often assigned the most dangerous tasks, including tunnel blasting, they died in the hundreds, usually without medical care. Head engineer Henry Cambie recorded Chinese deaths during a somewhat uneventful two-month period: one knocked into the river by a falling rock, one crushed by a rolling log, one buried in a rock slide, another smothered in a cave-in, while an unknown number drowned when their boat overturned in the Fraser River. Typical of white attitudes that did not take note of Chinese workers, the Yale Sentinel reported “no deaths” had taken place over the same period. Restricted to a diet of vegetable-free rice and ground salmon, shivering in drafty tents during the winter, more fell victim to scurvy and other diseases. All told, as many as six hundred Chinese workers are estimated to have died before the CPR’s last spike was driven by the railway’s well-dressed, top-hatted directors at Craigellachie in 1885.

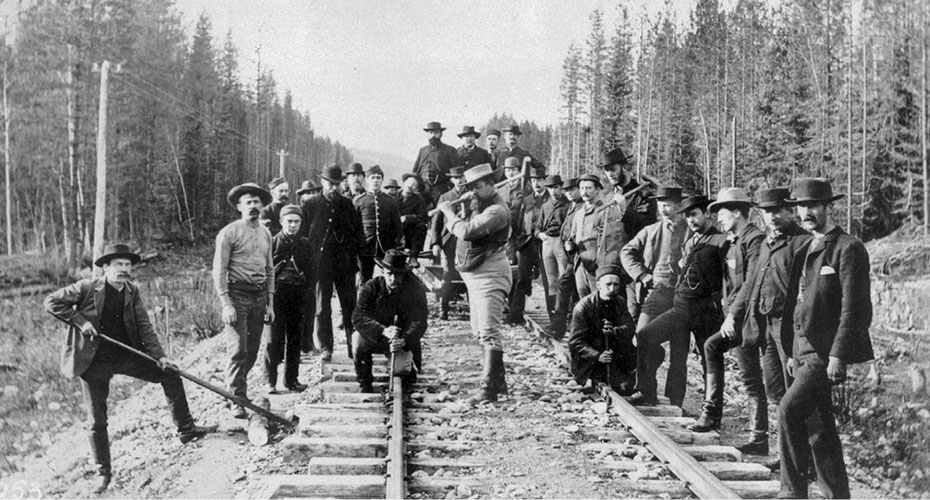

On the same day, Nov. 7, 1885, that CPR railway tycoon Sir Donald Smith drove in the last spike of the national railway near Revelstoke (top), some of the workers who built the railway posed for their own last-spike ceremony (bottom).

Images E-02200 and C-00618, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

From their princely pay of a dollar a day, Chinese railway labourers still had to pay for their passage from China, their contractor, clothes, tools and other incidentals. It was difficult to save more than $40 a year. Few made it back to China. Those in charge praised them as good, honest workers who mostly lived up to the terms of their contracts. But they were not passive. Brawls and work stoppages erupted if they felt they were being shortchanged or needlessly exposed to danger. It was estimated that hiring Chinese “coolies” saved Onderdonk and the CPR between $3 and $5 million while helping to suppress wage demands from white railway workers. “Either you must have this labour, or you can’t have the railway,” declared Prime Minister John A. Macdonald.

As the railway neared completion, however, the establishment’s real attitudes emerged. Once-valued Chinese workers were abandoned in their remote camps without transport and little food and water. Only intervention by some Vancouver charities rescued them from their plight. While the CPR was under construction, Macdonald had resisted persistent demands from British Columbians to restrict Chinese immigration. But when they were no longer needed, he moved quickly to impose a fifty-dollar head tax on Chinese immigrants. This made good on his avowal two years earlier that the federal government could stop Chinese immigration at any time “and therefore there is no fear of a permanent degradation of the country by a mongrel race.”

Back on the mining front, Dunsmuir had bought out the last of his original partners in 1883 and brought his sons into the operation. James Dunsmuir, who became mine manager, was perhaps even more anti-union than his father. The Dunsmuirs, and the mines themselves, did much to stoke workers’ militancy. Vancouver Island’s nineteenth-century coal mines were dank, dirty and exceedingly dangerous. Fatalities were so commonplace that the primary purpose of many early miner organizations was providing funerals and pensions for the widows. The mines provided such a steady flow of customers that one local furniture manufacturer ended up focusing on caskets and undertaking. Suffocating gases, flooding, rock mishaps, roof collapses and accidental explosions exacted a terrible toll. Mine inspections were lax, the dangers of certain work practices and coal-dust accumulation not readily understood. Safety lamps tended to be shunned by the miners, who preferred open-flame lamps because they provided more light.

On May 3, 1887, deep in one of the Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company slopes under Nanaimo Harbour, a poorly placed shot of black powder caused an outward blast that set off a series of escalating coal dust explosions that spread quickly through the entire mine. Those not killed immediately were trapped, scratching heartbreaking messages in the ground as their oxygen ran out: 150 men lost their lives, 46 women their husbands and 126 children their fathers. Among the dead were 53 Chinese workers, identified only by payroll numbers: “Chinamen 89, 100, 95, 84, 123 …” “I heard a sound like a heavy fall of rock, and then I felt the wind coming up the slope,” survivor Jules Michael reported. “When I felt the rush, I said, ‘My God, boys! What is coming on us now?’” Among the victims were many pioneers from the very beginning of coal mining on the Island, including Archibald Muir, one of those clapped in irons more than thirty-five years earlier in Fort Rupert. It remains the worst mining disaster in BC history and the second worst in Canada.

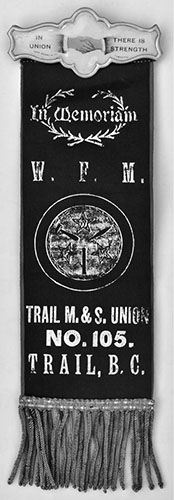

So common were mine fatalities that the reverse side of early miners’ union ribbons was black, so they could easily be turned into ribbons of mourning.

Courtesy David Yorke.

Barely eight months later, a second calamity rocked the close-knit mining community, this one at Dunsmuir’s operation in Wellington. A methane gas explosion ripped through the mine’s eastern slope, taking seventy-seven lives. These two catastrophic explosions occurring so close together gave tragic fuel to a long-simmering demand by the region’s white coal miners. Although there was no evidence implicating Chinese workers in either disaster, the cry to ban them from the area’s mines as a danger to safety soon swept aside any opposition. At a huge meeting in the opera hall, with emotions still raw from the heavy loss of life, not even Robert Dunsmuir could withstand the feelings of the community. To great cheers, he vowed to ban all Chinese workers from the payroll of his Wellington mine.

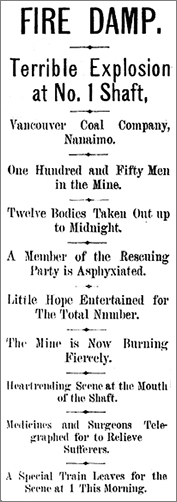

The front page of Victoria’s British Colonist newspaper headlines the Nanaimo mine disaster in 1887, the second-deadliest in Canadian history.

British Colonist, May 4, 1887, p. 1.

Crowds and families, including several Indigenous women, wait desperately for news after the lethal 1887 explosion at the Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company’s Number One Esplanade mine in Nanaimo. The blast claimed 150 lives.

Image C-03711, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

But the Dunsmuirs resolutely refused, even in the face of provincial legislation prohibiting all Chinese coal miners from working underground, to stop employing them at their large unionized mine in Cumberland. Eventually, in a landmark constitutional case, the British Privy Council overturned BC’s legislation, ruling that it was a matter of federal jurisdiction. In a brazen show of nerve, James Dunsmuir docked his Chinese miners fifty cents a month to help pay his court costs. They responded with a one-day strike and Dunsmuir relented.

In spite of their knock-downs, miners kept getting up off the mat and continuing to fight. They had struck and lost in 1883, and were again humiliated by Robert Duns-muir in a short-lived dispute in 1889. When a miners’ delegation tried to reason with him, he advised them, “Tell the men that I am a stubborn Scotchman, and that a multitude cannot coerce or drive me.” The words could have served as his epitaph, notes historian Jeremy Mouat. Three months later Robert Dunsmuir was dead, and the reins of R. Dunsmuir & Sons were taken over by his son James.

By then, coal production in the Nanaimo area was at record levels, split among mines owned by the New Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company (NVCMLC), the Duns-muirs and the small East Wellington Coal Company. Nanaimo was no longer a rough, isolated frontier town of small houses and muddy streets. There was a railway to Victoria, steamship runs to and from Vancouver, a real estate boom, schools, manufacturing, a good newspaper, electricity, sports teams, a renowned brass band and an opera house. But class tensions were ever-present, fanned by the Dunsmuirs’ fervent anti-unionism.

The difference between the Dunsmuir mines and those of the NVCMLC was stark. Rather than Dunsmuir-style company housing, their larger rivals provided five-acre lots to their workers, limited underground shifts to eight hours and recognized their union. The Dunsmuir mines had longer workdays, lower wages, no gas and pit committees to look after safety, and of course, no union. Strikers were blacklisted and union sympathizers regularly fired. Despite these conditions and their humiliation just a year before, Dunsmuir miners were ready to take on the company yet again in 1890. While there was some grudging respect and even admiration for the elder Dunsmuir, few had a good word for the thirty-nine-year-old, hard-nosed James Dunsmuir.

On February 1, 1890, a thousand boisterous miners packed the new opera house to back a new union. The Miners’ and Mine Laborers’ Protective Association (MMLPA) represented a majority of all Nanaimo and Wellington miners for the first time. It was a heady start for the fledgling organization. Members successfully petitioned the legislature to ban Chinese underground miners. On May Day the union staged the grandest event in Nanaimo’s young history, a gala gathering at the opera house. A train was chartered for the Wellington miners. Brass bands played and dancing went on until four in the morning.

A few weeks later after another spirited day of marches and music, the union was ready to take on Dunsmuir’s Wellington mine for yet another round, demanding union recognition and an eight-hour day. “The day is [past] when we must go to the rich man’s door and beg,” vowed union leader Tully Boyce at a mass outdoor meeting. This time strike leaders had a strategy. In an impressive show of cross-border solidarity, union workers on the docks of San Francisco readily agreed not to handle Dunsmuir coal, strikebreakers were “talked to,” convincing many to leave, and public sympathy soared when the miners peacefully complied with notices turning them out of their company homes. The mayors of New Westminster and Victoria offered money and tents, and the freshly formed Vancouver Trades and Labor Council (VTLC) held a large public fundraiser.

Still, despite the union’s best efforts, Duns-muir managed to hire enough strikebreakers to resume mining operations in early August. A few days later, several hundred strikers gathered to accompany the scabs to the pithead, then jeered them back to town. Dunsmuir and his government allies jumped on the minor incident. A day later, fifty-five militia men were dispatched by magistrates in Victoria to keep the peace that already existed. Although five strikers were arrested for intimidation, the push to discourage strikebreakers continued. Among the successes was a group of thirty black labourers brought in from Comox who refused to work, while a number of strikebreakers hired in San Francisco wound up in the pub sharing a pint or two with the strikers instead, and headed elsewhere.

The militia’s presence actually increased local support for the strikers. Hotels offered the strikers free drinks, a travelling theatre troupe staged a benefit performance, and two thousand supporters participated in an exuberant September parade with myriad floats and banners proclaiming, “We Can Stand Cold and Hunger But Not Injustice.” So much donated money flowed in, along with a siphoned 10 percent of wages from non-striking NVCMLC miners, that the union was able to double its strike pay. The MMLPA union worked feverishly to muster national and international support. Leaders sent a three-person delegation to Ottawa to seek help from the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada (TLC). The group included Thomas Salmon, an Aboriginal union member who so impressed those he encountered that he met John A. Macdonald and was asked to chair a TLC committee.

The Nanaimo-based coal miners’ union and its inspiring strike, along with a new desire to increase the political clout of the working class, led to the formation of British Columbia’s first provincial labour federation toward the end of 1890. Twenty delegates from the labour councils of Vancouver, Victoria and host Nanaimo attended the gathering. MMLPA president Tully Boyce was elected to head the organization. Although the provincial federation did not last, it amplified the voice for key union issues such as the eight-hour day, opposition to Chinese immigration and expanding commitment to political involvement.

Farsighted strike leaders continued to work hard to expand union solidarity beyond Vancouver Island. Even legendary US craft union leader Samuel Gompers, not known for radical rhetoric, weighed in, calling the Dunsmuir operation “one of the most villainous, grasping corporations that ever lived.” But the company’s relentless efforts to import strikebreakers was paying off. Nearly three hundred were working at the Wellington mine by the end of the year. And the onset of rainy, chilly, sometimes snowy weather significantly worsened life in the strikers’ tents, strung out in the words of one observer like “a second Gettysburg.” When a procession of non-union members riding back to town was pelted with a flurry of hard-packed snowballs, the pro-Dunsmuir government responded by arresting sixteen strikers at their next march to the mine and charging them with intimidation.

Before the next union action could even begin, the Riot Act was read, making mass gatherings illegal. After a rousing version of “La Marseillaise,” the miners dispersed. A large number of women responded with their own “March for Female Suffrage” through the streets of Nanaimo. When a taunting youth struck one of the women with the back of his hand, she took after her assailant, calling him “a blackleg son of a bitch” and threatening him with a rock. But the ban on union marches sapped the miners’ spirits. Working miners began to question giving some of their wages to the strikers, whose ranks had dwindled as the strike dragged on into a second summer. Some hearts remained strong. “I am keeping the marrow on my bones, and not letting it go out,” said one. Yet they knew the jig was up. In November, strikers voted by secret ballot to end their eighteen-month walkout.

It was a bitter defeat. More than twenty years were to elapse before the tough miners of Vancouver Island were ready to take on the Dunsmuirs one last time. In the meantime, they lost none of their class consciousness. Instead of strikes, they poured their energy into politics and the wave of socialism that was beginning to sweep the province. Nanaimo became a centre for radicalism and hostility toward the ruling class in British Columbia.

Although the fighting miners of Nanaimo spearheaded nineteenth-century labour resistance to the forces of capitalism, they had not been alone in the struggle to advance the cause of BC workers. In fact, the first appearance of a union occurred less than a year after the 1858 gold-rush flood engulfed Victoria, when a local newspaper notice announced formation of the Bakers’ Society, which resolved to protect its trade and regulate “the wages of journeymen” so they did not have to work on Sunday. What happened to the society after that is lost in the mist of time, but no record exists of an earlier labour organization. Other unions followed, representing workers such as printers, shipwrights and construction trades. Almost all were relatively small craft unions organized around a specific skill rather than covering an entire work site.

It was only with the dramatic charge to the economy brought on by the transcontinental railway that jobs increased and workers outside Nanaimo began to rally around the flag of the proletariat. Much of the fervour came from the arrival of the Knights of Labor. The Knights started out as a secret holy order for working people in the United States. It soon progressed to a high-profile force that pressed for labour reform, particularly an eight-hour day, and raising the status of workers in society. Unlike closed-door craft unions, the Knights of Labor was open to anyone who was white and worked for a living. At its peak in the mid-1880s, one in five US workers belonged to the Knights, before internal divisions and structural problems precipitated a rapid decline.

The Knights also struck a chord with BC workers, who were frustrated by a succession of losing strikes and failure to make any headway on such broad issues as shorter working hours, mine safety and wage competition from increasing numbers of Chinese immigrants. These matters, they began to realize, needed to be addressed beyond their immediate workplace. The Knights’ first assembly in BC was in 1883 in Nanaimo, where they operated a successful co-operative store providing members with goods that were cheaper than the Dunsmuir company store.

Over the next three years, a dozen other assemblies came into being, representing a cross-section of industrial workers stretched across the southern half of the province. The Knights had close ties with the province’s first labour newspaper, Industrial News, published in Victoria. The Knights also backed the first organized attempt to elect pro-labour candidates. Two in Victoria and two in Nanaimo, including Knights’ organizer Sam Myers, were nominated by the new Workingmen’s Party to run in the 1886 provincial election. Although all four were trounced and the party soon disappeared, historical researcher Thomas Loosmore points to its platform as the first political articulation in BC of conflict between “the toiling masses” and “the wealthier part of the community.”

The strongest rallying cry in the Knights’ growing ranks focused on putting a stop to Chinese immigration and their cut-rate wages. In testimony to a Royal Commission on Chinese immigration in 1885, Knights’ representative F.L. Tuckfield said that with no families and able to live “on a few cents a day,” the Chinese labourers “will make the white man powerless to compete against them for labor.” This anti-Chinese hostility fired much of their political agitation. In the new Vancouver rising from the ashes of its devastating 1886 fire, the Knights demanded pledges from mayoralty candidates to ensure a Chinese-free city and pressured employers not to hire Chinese workers.

Sometimes these feelings instigated vigilante action. In November 1887, members of the Knights of Labor were widely thought to be responsible for painting black X’s on the windows of houses employing Chinese workers and on the sidewalks outside stores and offices doing business with them. Early the next year, emotions erupted into violence when a contractor brought in Chinese workers from Victoria to clear a large tract of land in Vancouver’s West End. That night, in a precursor to the infamous 1907 Chinatown Riot, a large mob attacked and burned the Chinese camp, pummelling those who were slow to leave. As they dispersed under police orders, some rioters looted Chinese homes and set fire to a few buildings. Only the arrival of dozens of special constables dispatched by the provincial government allowed the land to be cleared and more Chinese immigrants to work in the city at other jobs.

During its relatively brief existence, the Knights of Labor attracted a diverse membership of miners, loggers and mill workers, teamsters, stevedores, railway workers and general labourers. As in the United States, the Knights of Labor soon faded, done in by its generalism and the rise of more specific unions. Despite its anti-Asian racism, it was nonetheless the first labour organization in the province to give workers a voice in fighting repression on a wider battlefield. The torch was there for the passing.

However short, the Knights’ success attested to the outbreak of new industrial activity in the province. Sawmills dotted the shores of Burrard Inlet, logging crews ventured into the dark, wet woods to harvest immense cedars and Douglas firs, workers laboured on the roughly built docks of Vancouver to load ships carrying BC resources to markets in Europe and Asia, railway lines proliferated, and the discovery of silver and other precious metals was transferring the Kootenays into a mining hotbed. Yet none of these topped the surge of the salmon fishery; what began as a fishery conducted almost entirely by Indigenous people quickly became the province’s number-two industry. Returning every year in numbers supplying both feasts and daily needs, the salmon were fundamental to First Nations’ existence throughout BC. Now the colonizers had decided to get in on the action to meet the growing demand for canned salmon overseas.

Because of the need for capital, organization and some technology, the canning rush was initially confined to only a dozen or so entrepreneurs. They were a hard, diverse lot. The names of John Sullivan Deas, an adventurous black man from the United States, and short, squat T.E. Ladner remain a part of the Lower Mainland today. Another canner, Henry Ogle Bell-Irving, who hated strikes with a passion, was the patriarch of one of the province’s most illustrious families of the twentieth century.

Despite their personality differences, the canning entrepreneurs shared a similar goal of amassing huge profits for themselves while keeping others out. These capitalists regarded free-enterprise competition as a virus to be avoided. In 1888 the wealthy canners formalized their oligarchy with the establishment of the BC Fisheries Association. Together they took on all comers: governments trying to regulate the fishery, newcomers wanting to get in on the action, and fishermen seeking better wages and prices. Subsequent cannery associations with similar goals followed for decades to come. Canning operations soon spread to rich salmon runs along the Skeena and Nass Rivers in the north and at Rivers Inlet on the central coast. By 1900 the Fraser supported forty-two canneries, the Skeena and Nass eleven each, and Rivers Inlet six.

Cheap labour was fundamental to the bottom line. The canneries provided an abundance of seasonal jobs for those at the bottom rung of the workforce: Chinese men and Indigenous women. Both groups were critical to the industry’s rapid expansion and the boost it gave the BC economy. Under intense pressure to maintain production as the fish piled up, their work was beyond strenuous: long days spent in dark and noisy assembly-line sweatshops. Mostly, First Nations women did the cleaning, trimming and canning, while Chinese workers did the butchering. The vitriol aimed at them in other industries was absent in the canneries, because no whites wanted these jobs. The canners were appreciative. “But for cheap labour, I do not think there would be so many canneries in existence,” canner Alexander Ewen told a second Royal Commission on Chinese immigration. Bell-Irving advised the commission that Chinese men, ostensibly content with rough accommodation, were less trouble and less expensive than whites. “I look upon them as steam engines or any other machine.”

During the canneries’ first fifteen years, Indigenous men did almost all the fishing. But as the demand for salmon soared and canneries multiplied, they gradually began to be crowded out by whites and fishermen from Japan. By 1893, Indigenous British Columbians made up but a third of the estimated 2,350 fishermen on the Fraser. The canners had taken advantage of the numbers to switch to paying many fishermen per fish rather than a daily rate. With intense competition on the fishing grounds, they kept lowering the price, pumping up their substantial profits even more. When the canners offered a mere six cents a fish before the 1893 salmon runs, fishermen from all groups—white, Indigenous and Nikkei—realized they had to take a stand. The result was the first major strike in the BC fishing industry.

White fishermen now had a union, the Fraser River Fishermen’s Protective and Benevolent Association. Numerous Indigenous fishermen also signed up. But racism complicated union resistance. Union members rejected their Nikkei counterparts’ request to join. Instead, they called for a complete ban on Nikkei fishing licences. Although the numbers of immigrants from Japan never approached those from China, their arrival in British Columbia had been both sudden and dramatic. From a mere handful before 1890, the number of Nikkei workers grew to several thousand in just a few years. Some worked in the Dunsmuir coal mine in Cumberland but most took up fishing on the Fraser, encouraged by the canneries to help squeeze prices paid to white and Indigenous fishermen.

Cannery employees take a break from their hard work on the wharf at Alert Bay, where totem poles still stood in front of some oceanfront houses as the 19th century came to an end.

Image E-07419, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

On July 14, 1893, despite the racial split, all fishermen came off the river, demanding an increase to ten cents per fish from the six cents offered by the canners. There is nothing quite like the drama of a salmon strike. Salmon pay no attention to above-water picket lines, heading upstream to spawn on their own biological clocks. If boats are tied up when their peak run passes, both canners and fishermen lose out big time. Each day the run nears, pressure for a settlement ratchets up like a high-stakes poker game.

Stunned by the strike, the canners were determined not to blink first. They immediately petitioned the local Nikkei consul to send in scab fishermen and Department of Indian Affairs officials to pressure Indigenous fishermen to abandon their tie-up. Although some Nikkei fishermen held out to the end, many were soon out on the fishing grounds after the canners agreed to a firm price of seven cents a fish. Most Indigenous fishermen continued to support the strike. At a large public rally in Vancouver, Indigenous union members told the crowd that Indian agents, who had been trying to pressure them back to work, should look after Indigenous interests and not those of the canners. A reporter’s account of the rally in the Vancouver World concluded, “The Indians fully understood the grievances of the white fishermen and being in sympathy therein, had joined the union.”

But with the big run approaching, with a worrisome number of Nikkei fishermen on the water and white fishermen also starting to trickle back, the union was out of cards to play. After a tough ten days leaders called off the strike. Among the last to return were militant fishermen from the Cowichan First Nation (who went on to form their own union local in 1900). Indigenous fishermen staged three further strikes on the Skeena and Nass Rivers before the century was out. As with many lost strikes in the nineteenth century, the 1893 fishing dispute was a significant struggle nonetheless. No longer would rapacious canners rule the rivers unchallenged. At the same time, the outcome revealed once more the difficulty of prevailing when workers were divided by race. These racial divisions were exploited by employers over and over.

Although certainly the most dramatic, the decline in their share of the salmon catch was not the only evidence of diminishing economic opportunities for the province’s Indigenous people. As BC moved inexorably toward a functioning capitalist economy in the latter years of the nineteenth century, Indigenous workers were being swept aside by a flood of immigrants from everywhere, many with the colonialist attitude that the province was theirs. The accelerating demand for full-time, year-round workers, plus increased automation, loss of their rights and outright discrimination cut into the ability of First Nations people to earn a living. No longer were employers willing to adapt to Aboriginal employees coming and going with the seasons, leaving their jobs as winter approached for their annual round of village potlatches and ceremonial dances. Their right to vote had been extinguished. Deadly epidemics continued to slash their population and they were arbitrarily confined to small reserves, the only Indigenous people in Canada to have their traditional territories stripped away without a treaty. Slowly, their traditional hunting and fishing rights began to disappear too, victims of new regulations and requirements to have a licence. Indian superintendent A.W. Vowell put it bluntly in 1894: “The Indians do not now, nor can they expect to in the future, make as much money as formerly in any line of industry or business.”

Unions on the other hand were becoming more numerous and willing to flex their muscles. Many had international connections, like the Victoria local of the American Brotherhood of Carpenters that staged a successful strike for a nine-hour day in 1884. Other newly organized craft unions with international charters included the iron moulders, typographers, painters, plasterers, bricklayers and masons. All were soon agitating for the same nine-hour day won by the Victoria carpenters. Whether eight or nine hours, a humane, defined workday was a central plank in all labour platforms. Strikes over the issue were common. To up their organized clout, unions began establishing community labour councils, most prominently in Nanaimo, Victoria and Vancouver. It was time for political action.

On a fine day in May 1890, a straight- shooting, Belfast-born coal miner stood before a crowd of eight hundred fellow miners and sympathizers at a mass public meeting in Wellington. “Do not believe the capitalist will advance your interests and wants,” he told the meeting, to great cheers. “The only man who will do this is the workingman.” The gathering, organized by the new miners’ union, and Thomas Keith’s proclamation marked a turning point in the ongoing struggle of workers in British Columbia. After a succession of losing strikes to the Dunsmuirs and petition after petition ignored by the provincial government, Nanaimo-area coal miners concluded they needed to enter politics themselves.

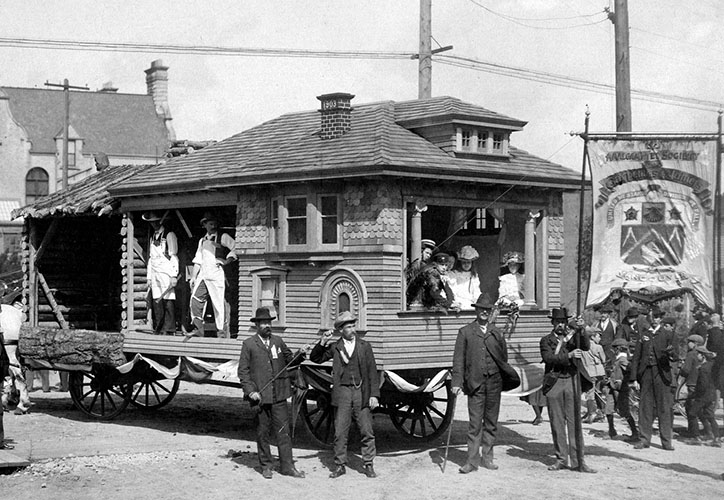

Proclaimed a national holiday in 1894, Labour Day in Vancouver, a negotiated day off for all union workers, featured a celebratory parade with bands, floats and marching trade unionists. This horse-drawn float fronted the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners contingent in 1903.

Alfred A. Paull photo, City of Vancouver Archives, F1 P2.

The meeting chose Keith, former miner Thomas Forster and farmer C.C. McKenzie as labour-backed candidates for the three Nanaimo seats in the coming provincial election. The candidates ran on a platform calling for shorter working hours, safer work sites, tough anti-Chinese legislation and fairer taxation, including an onerous tax on public land given away to corporate interests and a then-radical proposal for a graduated income tax. All three were successful. When Thomas Keith took his place in the provincial legislature, he was the first member of the working class to do so. During his four years in Victoria, Keith showed the worth and shortcomings of electing your own, a conundrum that has not changed much over the past 125 years.

None of Keith’s pro-worker actions succeeded, but the electoral triumphs of Keith and his associates and the raising of labour issues in the legislature did not go unnoticed by mainstream politicians. The government approved a few matters sought by labour, while opposition members began to espouse further restrictions on Chinese workers and more significantly, the principle of an eight-hour day. Although the three MLAs were blanked in the 1894 provincial election, the die had been cast; in the next five elections, Nanaimo returned pro-labour candidates to the legislature. The Vancouver Trades and Labor Council soon had some success of its own supporting candidates, and union forces in the newly emerging mining belt of the Kootenays chalked up other electoral victories.

Ralph Smith of Nanaimo—coal miner, union leader, gifted speaker, inveterate politician and moderate—pressed for labour reforms, including the eight-hour day, during his up-and-down career that straddled the 19th and 20th centuries. His wife, Mary Ellen, was a prominent pioneer of women’s rights.

Image A-02467, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

Members of Local 119 of the Western Federation of Miners take time out from their union meeting to pose for a group photograph, complete with a baby, in April 1901, in the West Kootenays town of Ferguson.

Vancouver Public Library, 100.

Nanaimo miner Ralph Smith, a skilled orator who went on to play a significant role in labour and politics both provincially and nationally, was a key figure in these events. Although a relative moderate, Smith knew which side of the class war he was on. During his successful campaign in 1898, he lashed out at R. Dunsmuir & Sons, reminding constituents that “the throats of the people of the province had been grasped by a corporation that was prepared to throttle them without mercy.” The election resulted in a sharply divided legislature, giving Smith and a few other pro-labour MLAs leverage to bring about five pieces of legislation that were in the interest of workers.

One of them imposed an eight-hour day as the maximum underground shift in the mining industry. But miners found that once they had the eight-hour day, it was hard to keep, particularly in the heavy-metal mines of the Kootenays that had proliferated following the discovery of multiple rich ore bodies toward the end of the nineteenth century. Mine owners there bitterly resisted the change. “The world is made for the rich, and the poor are to work for them and be grateful for the privilege,” said one. Miners were equally determined to retain the reduction in working hours.

Their fight was led by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), then the most radical union in North America. At mine after mine throughout the western United States, the WFM had waged pitched, often violent war against special cops, Pinkerton agents, strikebreakers and ruthless mine owners to secure better pay and working conditions for union miners. As American miners spilled across the border to work the mines of the Kootenays, they brought their hard-rock union with them.

By the turn of the century, the Kootenays had thirteen WFM locals, bringing significant unionization to workers beyond the West Coast for the first time. Local 38 in Rossland, the first metal mines local in Western Canada, had been organized by the WFM in 1895. Rossland was a strong union town. Even the local newsboys were organized, staging three successful strikes in a single year. In 1898, Local 38 was strong enough to pay for and erect a substantial wood-frame union hall on Rossland’s main street that still stands. The eight-hour day was fundamental to the WFM cause. If miners were human beings “able to read, think, and appreciate the good things of life, as others do, then eight hours is sufficient for men to work underground,” the WFM declared in a brief to the legislature.

As their first ploy against the shortened workday, mine owners cut the daily pay from $3.50 to $3.00. A hard-fought strike by WFM miners in the silver mines around Sandon managed to get the rate up to $3.25, but their efforts were hampered by strikebreakers brought in from the United States, in clear violation of the federal Alien Labour Act. Companies took a different tack in the mines around Rossland. To avoid the daily rate, they began hiring miners on contract with pay based on output.

By July of 1901, the Rossland miners had had enough. At a heated meeting in the union hall, tired of the owners’ anti-union activities and lack of commitment to the eight-hour day, they voted to strike. Both sides knew the stakes were high. WFM president Ed Boyce came up to rally the strikers with a call for a fight to the bitter end. “I care not what it takes, nor how we win. I am in favour of winning,” he declared, pledging $20,000 in strike assistance from the international union.

The mine owners were equally determined. Their spies and shotgun-toting police were everywhere in town. Trainloads of non-English-speaking immigrant strikebreakers began arriving from the United States to keep the mines running. As in Sandon, this contravened the Alien Labour Act. But the government refused to enforce the act. When two strikers had the effrontery to heckle arriving scabs, they were sentenced to two months of hard labour. Increasingly desperate and running low on funds, the union invited future prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, then a twenty-six-year-old deputy labour minister, to Rossland to investigate the company’s willful violation of the Alien Labour Act. King quickly fell under the sway of the owners, shrugging off voluminous evidence of illegally imported scabs and advising the union to call off its strike. The Sandon Paystreak newspaper slammed King as “a cultural dub with a university education, a picturesque name and a thrilling ignorance of labor as a concrete sociological force.”

A heart-rending funeral procession through Fernie in the Crowsnest Pass, transporting 28 victims of the 1902 Coal Creek Mine disaster to the community’s small cemetery. The explosion and resulting fire killed a total of 128 miners.

Image D-01630, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

The new year brought defeat. After nine months, with no more strike pay and the law stacked against them, the miners, some close to starvation, voted to return to work. “No man living outside Rossland can imagine the troubles [we] have been through,” said one union miner. The mine owners weren’t finished. In the imposing courthouse purposely built opposite the miners’ hall, the companies were awarded $12,500 in damages from Local 38, forcing it into receivership. Afterward, concluding that laws made by the workers were the only way forward, many Kootenays miners became ardent socialists, pursuing victory by the working class and an end to capitalism. They would fight more battles in the years ahead, not a few of them over the ongoing quest for a permanent eight-hour day.

Farther east, the rich coalfields of the Crowsnest Pass were being opened up to give the province a second major coal-mining resource. But it was just as susceptible to tragedy as the underground mines of Vancouver Island. During the night shift on May 22, 1902, a horrific explosion and coal-dust-fed fireball ripped through the mine at Coal Creek eight kilometres east of Fernie. The first victim carted out was thirteen-year-old Will Robertson. By the time rescuers had finished their grim task, the official death toll was 128, the province’s second-deadliest mining disaster. Over the next few days, Fernie was consumed by the building of coffins, the digging of graves and a series of sad funeral processions down its frontier main street. Grief and anger were rife. When a new police constable was overheard expressing a cruel wish that more had died, hundreds of miners and residents gathered outside the police station, refusing to leave until he was put on the next train out of town. It was the first example of the class solidarity that would turn Crowsnest Pass coal-mining communities into a resolute left-wing stronghold for many years.