3 A New Century and New Labour Awareness

With the newly European-dominated population of 170,000 people, the province’s industrial muscle was in full swing. Settlers, workers and entrepreneurs poured in. Exports had soared from about $3 million in 1885 to $17 million by 1900. In 1901, fifteen years after burning to the ground, Vancouver had supplanted Victoria as the province’s largest city, with twenty-seven thousand residents. The end of the line for Canada’s transcontinental railway and the gateway to Asia, the city continued growing at a phenomenal rate, more than quadrupling its population over the next ten years. As for BC itself, by the outbreak of World War I nearly half a million people lived in the province.

The scattered skirmishes of the previous twenty-five years—when only the resistance of Vancouver Island’s coal miners stood out—were replaced by a harder edge that spread to most regions of the province. It was marked by a growing embrace of socialism by the working class that went beyond reforming capitalism to overthrowing capitalism and waves of industrial strife.

Unions deployed new weapons to fight for change: direct and political action, provincial and city-wide labour organizations to foster solidarity, civil disobedience, sympathy walkouts and general strikes—and on occasion, violence. They were stronger too, with organizers more committed than ever before. And socialism made its first appearance as a political force beyond impassioned rhetoric at rallies and meeting halls.

The fiery James W. Hawthornthwaite, first elected as a labour candidate in a 1901 Nanaimo by-election, soon became a committed socialist. Running under their anti-capitalist banner, he was returned to Victoria four more times by the coal miners of Nanaimo. During his first year as an MLA in 1902, Hawthornthwaite mustered enough votes for the passage of Canada’s first Workmen’s Compensation Act. Covering only railway, factory, mine, engineering and construction workers, the act nonetheless provided compensation levels for injured workers regardless of fault, and benefits equivalent to three years’ salary for families of workers killed on the job. Although there were holes in the act that ultimately lessened its effectiveness, it was a significant step forward for workers and an example of what could be achieved through political action.

Successful labour and socialist politician James W. Hawthornthwaite from Nanaimo was elected five times to the BC legislature. He was a sponsor of Canada’s first Workmen’s Compensation Act in 1902 and a founding member of the Socialist Party of Canada in 1904.

Image A-02210, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

Chinese fish plant workers unload salmon for a cannery along the Fraser River in 1897.

Stephen Joseph Thompson photo, City of Vancouver Archives 137-57.

The Socialist Party of BC—with a platform calling for female suffrage, old-age pensions, an eight-hour day for all workers, exclusion of Asians and an end to capitalism—elected members in each succeeding provincial election until 1916. In 1903, socialist and labour candidates received an impressive 15.9 percent of the total popular vote despite fielding far from a full slate, declining only slightly to 14 percent in 1907. Hawthornthwaite’s longevity was matched by fellow socialist Parker Williams, who was elected five times by working-class voters in the adjacent Nanaimo riding of Newcastle. Despite labour’s stepped-up fervour, nothing came easily. Arrayed against them were ever more prosperous and ruthless companies, pro-business governments, an anti-union press and authorities easily persuaded to unleash soldiers, police and special constables to preserve the existing order. Inevitably, setbacks occurred.

There was also the downside of labour’s ongoing campaign against Asian immigrants, a campaign that commonly included overt racism and once, in 1907, along with other citizens, a frightening rampage through Vancouver’s Chinese and Nikkei areas. While some, notably the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), preached that workers were workers regardless of race, that tolerance did not prevail. As shown by strikes in the fishing industry and other disputes where Chinese strikebreakers were used, this deep-seated racial division continued to be used by employers to keep unions at bay.

The Fraser River Fishermen’s strike of 1900 was the first major confrontation of the new century in British Columbia and the province’s first significant strike outside the mining industry. It marked not only the beginning of two years of open warfare on the water, but the start of twenty years of unsurpassed radicalism in the province’s long history of union struggle. After their defeat in 1893, fishermen were determined to reverse their fortunes, particularly with the dramatic changes that had overtaken the Fraser River fishery. Canners had lost their campaign to restrict fishing licences, and by 1900 they were being handed out like candy at Christmas. Close to thirty-seven hundred licences had been issued, more than triple the number in 1893. Most fishermen were now paid per fish.

Since there were only so many salmon, the licence explosion meant lower catches for everyone. Hardest hit were Indigenous fishermen, who had seen their share of the fishery severely diminished by the dramatic influx of fishermen from Japan. In seven short years, the Nikkei had gone from a few hundred licences to become the largest fishing group on the Fraser. Indigenous fishermen were left with only a third of the allotted licences. But tensions were inflamed among all fishermen when canners organized themselves into the Fraser River Canneries Association to set fixed quotas for each cannery and to unilaterally impose a maximum price for caught salmon.

The BC Fishermen’s Union emerged in the spring of 1900. Its many locals included Aboriginal fishermen from Cowichan and Port Simpson. Frank Rogers, a driven twenty-eight-year-old longshoreman and socialist, was hired to prepare for the looming confrontation. Rogers was a rare trade unionist with no outward racial animosity toward the Nikkei. Knowing no strike could be successful without their support, he quickly set to work to bring them on board. With an interpreter, he made the rounds of their rough bunkhouses, urging them to join the union and explaining the need to stand firm on prices. Instead, the Nikkei formed their own association, the Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Society. Although less a union than a cultural and social welfare group working to build a hospital and school for the swelling Nikkei community in Steveston, the society also functioned as an advocacy group for their fishermen.

But Rogers’s efforts bore some fruit. All three ethnic groups—Nikkei, whites and Indigenous—united on a demand for twenty-five cents a fish throughout the season. When the canneries stuck to their usual guns of refusing to negotiate, the historic strike was on. By the time it ran its course nearly a month later, the dispute had seen just about everything. Shortly after the strike began on July 8, 1900, a group of Nikkei fishermen went out to fish anyway. Union patrol boats herded them back. A parade of union fishermen, accompanied by an interpreter, repeated Rogers’s bunkhouse visits to explain the strike. The next day, all Nikkei boats remained on shore.

The strike remained solid for the next two weeks. Fundraising and food donations helped feed hundreds of strikers every day, many of them Nikkei. Regular meetings at the Steveston Opera House buoyed spirits, and a large, uplifting demonstration in Vancouver drew more than a thousand marchers led by the famous First Nations brass band from Port Simpson. Stunned by the solidarity, the canneries became increasingly anxious. After attempts to have the militia sent in failed, they reluctantly appointed a negotiating committee and began talks with the union. At one point, the gap narrowed to a mere two cents per fish—eighteen cents from the canneries to twenty cents demanded by the fishermen’s committee. But talks broke off when the companies declared their offer final. Nikkei, white and Indigenous fishermen all rejected the canners’ ultimatum; never before had so many, across all races, held out for so long to force a better price for the fish they caught.

A mass march of fishermen toward the village of Steveston during the big showdown with Fraser River canners in 1900.

Henry Joseph Woodside/Library and Archives Canada/A016346.

The pace of events began to quicken. On the evening of Friday, July 20, one of the Bell-Irving canneries deliberately sent two non-union boats out to fish, protected by three tugs carrying ten special constables. A union patrol boat went after one of the vessels and forced it to shore, where Frank Rogers and an agitated crowd awaited. Rogers hauled the skiff’s boat-puller up on a soapbox and cuffed him about, amid loud jeers of “Scab!” The strikebreaker was then jostled by the fishermen before being let go. The trivial incident prompted a flurry of hysterical pleas to Victoria urging that forces be sent in to curb a “state of lawlessness” on the river that risked “a great loss of life and property.”

The canneries were also preparing an-other final offer. This one promised twenty cents each for the first six hundred fish caught each week, and fifteen cents per fish after that. More than thirty-five hundred Nikkei community members, by far the largest crowd in Steveston’s short history, gathered to consider the new offer. After ninety minutes of speeches, including a forceful address by the driven, outspoken secretary of the Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Society, Yasushi Yamazaki, the offer was accepted unanimously. The ensuing cheers could be heard a mile away. A huge, spontaneous procession wound through the muddy streets of Steveston to celebrate. Once again, the canneries had managed to drive a racial wedge between their adversaries.

Two hours later, members of the BC Fishermen’s Union marshalled a force of their own. On short notice, six hundred white fishermen crowded into an angry meeting, calling for hundreds of trade unionists from Vancouver to rally to their aid. More than a few threatened to throw any Nikkei found fishing into the Fraser. The boats of white and Indigenous fishermen would remain tied up after an overwhelming secret-ballot vote to hold out for twenty-five cents. It was a critical turning point in the most intent effort thus far by Fraser River fishermen to crack the stranglehold that the corporate canneries had imposed on the rich salmon fishery.

The canneries quickly cajoled three compliant local justices of the peace to requisition two hundred militiamen to protect the Nikkei fishermen the next morning. Ammunition was handed out and the troops took up positions around the docks. Out sailed the Nikkei fleet, likened by a reporter to “a large and beautiful crowd of butterflies, against the western sky.” Somewhat less entranced, striking fishermen watched helplessly from shore. With fifteen hundred Nikkei boats now hauling in salmon, the strike appeared lost. But there was no loss of spirit. White and Indigenous fishermen amassed on a local meadow that afternoon, vowing continued resistance.

Several chiefs were among those who addressed the crowd. Other speakers made a point of praising Indigenous fishermen for standing firm. When Frank Rogers suggested it was time for their own march to match the militia’s parading about, one of the more colourful events of the strike ensued. Up to five hundred fishermen proceeded to the main military post outside the Gulf of Georgia Cannery. In a festive mood, they spent the afternoon parading around the soldiers. Mocking them as the “Sockeye Fusiliers,” they jeered and ridiculed the young, straw-hatted troops and serenaded them with a derisive rendition of “Soldiers of the Queen.”

Surprisingly, the canneries continued to fret, despite the Nikkei return to fishing. Many were failing to bring in much of a catch. As well, the salmon run stayed light. With more than half the fleet remaining on strike, the canners were still short of fish and worried they would be unable to take full advantage once the largest run of salmon hit the Fraser. They were also under intense pressure from an angry public, newspaper editorials and the legislature, miffed by the canners’ underhanded role in summoning the militia against mostly peaceful fishermen. Much against their will, they approached the white and Aboriginal fishermen once again.

Rogers, a realist and skilled strategist, knew it was time to settle. He persuaded the fishermen to propose a new bottom line of twenty cents per fish for the full season, plus recognition of the union. During two days of tense talks, the fishermen reduced their demand to nineteen cents, a cent less than the Nikkei were receiving for their first six hundred fish of the week, but it would be a firm price with no reductions. The canners agreed. Even then, hungry and broke, the strikers did not stampede back to the fishing grounds. In what historian Keith Ralston called “a last display of the discipline and loyalty to their organization that had brought them to a negotiated settlement,” the fishermen delayed their return for a day to allow for a formal vote on the agreement. They started fishing at the crack of dawn on July 31, 1900.

While the union failed to win union recognition and the price they wanted, unwilling canners had been forced for the first time to negotiate a fixed price per fish for the entire season. When the salmon run proved heavier than expected, the union’s deal turned out to be better than that accepted by the Nikkei. Heartened by their relative success, union leaders began plotting strategy for 1901. This would be what the industry called a “big year,” when the four-year cycle of salmon hits a peak, flooding BC rivers with astronomical numbers of fish returning to spawn.

In the fall of 1900, the Grand Lodge of BC Fishermen emerged as BC’s first coast-wide fishing union. First Nations fishermen from Cowichan and Port Simpson, with their ever-popular brass band, were among the most militant of the many locals. In fact, First Nations played a much stronger role in the 1901 showdown than they had in 1900. Following a large meeting in Chilliwack, thirty-three chiefs agreed unanimously to reject the canners’ offer of twelve and a half cents to start the season and a lower price once the heavy run began. The Nikkei settled first, accepting twelve and a half cents, but with a 250-fish daily limit after August 3, 1901. White and Indigenous fishermen held out for a firm price of twelve and a half cents for the full season. “At one time, the Indians owned the whole country, the rivers, everything,” declared Chief Jimmy Henry as he supported the call for strike at a mass union meeting in late June.

The celebrated Tsimshian brass band from Port Simpson marches along Hastings Street in Vancouver during a holiday parade in the city, likely Dominion Day. In mid-July, the same band led a thousand-strong march in support of striking fishermen, whose ranks included many Indigenous members. A few days later, the band was in Nanaimo to help rally local union coal miners to the cause.

John Tyson photo, City of Vancouver Archives, P120.1.

The resulting tie-up was shorter but far more intense than the previous year’s confrontation. Desperate to cut off delivery of fish by the Nikkei, striking fishermen went all out on the water. After one crew was severely beaten, a score of armed patrol boats sailed out to protect the Nikkei fishermen, rumoured to have been given guns. Frank Rogers called on picketers to arm themselves in self-defence. During the next few days, picketers boarded a number of Nikkei boats, cut their nets, tossed their weapons overboard and brought the men ashore, setting their boats adrift. On July 10, gunfire broke out on the waters off Point Grey. Six strikers found to be carrying four shotguns and a revolver were arrested by police on board one of the Nikkei vessels and charged with intimidation.

Nikkei fishermen at the old Ewens cannery on Lion Island in the south arm of the Fraser River, 1913. Many of their sons and grandsons became members of the Fishermen’s Union.

UBC Rare Books and Special Collections, 1532-1324.

Not long afterward, union picketers abducted as many as a dozen Nikkei fishermen and marooned them on Bowen Island. News of the kidnappings became a newspaper sensation. The drama was then heightened even further thanks to the ubiquitous Yasushi Yamazaki. After arranging their rescue, Yamazaki brought the abducted Nikkei fishermen to court, where they fingered Frank Rogers as one of the culprits. There to support the six strikers, Rogers was quickly arrested and charged with kidnapping and possession of a concealed weapon. The union leader was held without bail for six months as the Crown tried and failed twice to convince a jury to convict him. After the first trial, held in Vancouver, the Crown’s lawyer complained that it was impossible to convict Rogers in “a union town.”

But with Rogers in jail, Nikkei boats fishing and a massive salmon run on its way, union fishermen resentfully accepted the canneries’ terms and headed out to harvest what turned out to be the greatest run in the recorded history of the Fraser River. Despite a breakthrough in establishing the practice of negotiating fish prices, the fishermen’s bitter struggles of 1900 and 1901 ended with the canners ruling the Fraser. The next year many canneries consolidated into the formidable BC Packers Association, which would dominate the industry for the next ninety-five years.

Alone, it seemed, Indigenous fishermen kept fighting back. They regularly denounced weak union agreements and continued to demand Nikkei fishermen be gone from the fishing grounds. A major confrontation took place on the Skeena and Nass Rivers in 1904. Close to eight hundred First Nations fishermen refused to fish for the offered prices. As in all strikes involving the First Nations, Indigenous women cannery workers also refused to work. Once again, many Nikkei eventually began fishing and the strike died out. But three years later, with a labour shortage in the canneries, Indigenous women struck successfully for a higher wage on the production line.

But ethnic divisions among all BC fishermen continued to plague solidarity on the grounds. A 1912 strike by Indigenous drag-seine fishermen on Vancouver Island was undermined by white fishermen willing to fish for less. And a strike by Nikkei fishermen in 1913 foundered after Indigenous and white fishermen accepted the companies’ deal. According to newspaper reports, the Nikkei strikers used violence and intimidation to keep other fishermen from setting their nets. Such incidents were telling. There would be no chance of standing up to the fish companies on an equal basis as long as the industry was wracked by what fishing historian Geoff Meggs called “the corrosive effect of racism.”

Most early South Asian immigrants made their way in the province’s booming forest industry. In 1910, these men worked for the North Pacific Lumber Company at Barnet (today part of Burnaby).

Phillip Timms photo, Vancouver Public Library, 7641.

The early twentieth century also brought another influx of Asians from across the Pacific that drew white labour’s ire. Enticed by reports from visiting South Asian soldiers that British Columbia was a good place to work and live, upwards of five thousand immigrants from India, mostly South Asians from the Punjab, had made their way to the West Coast by 1908. Many found employment in sawmills, establishing themselves as hard-working, dependable and, yes, cheap labour. Their growing numbers set off the same racism and union opposition that dogged immigrants from China and Japan. Both the Victoria and Vancouver Trades and Labor Councils protested the entry of “Hindoos” into the workforce. Levelling the familiar charge that they undercut wages and conditions for white workers, the labour organizations called for banning “the hordes of Asiatics” from the forestry, mining and fishing industries.

Although citizens of the British Empire, South Asians were denied the right to vote by the provincial government in 1907, the same basic right Asian immigrants from China and Japan had lost earlier. The next year, an extraordinary order-in-council by the federal government restricted future immigration to those making a direct, nonstop passage from India. No such passage existed. When 376 South Asian passengers, many of whom boarded at ports outside India, boldly tried to challenge the restriction in 1914, they were left marooned in Vancouver Harbour for two months aboard the Komagata Maru before being escorted back out to sea by Canada’s only warship. A century later, the incident is widely recognized as a black mark on Canada’s and British Columbia’s racist past, along with the Chinese Head Tax, Nikkei internment and residential schools. All have generated formal government apologies.

Barely a thousand South Asians remained in 1920. But they continued to be a fixture in coastal sawmills, typically assigned to arduous tasks on the green chain or otherwise moving lumber while being paid significantly less than non-Asian workers, even at mills run by South Asians themselves. Only with the admission of women and children under a grudging family reunification program did BC’s tightly knit South Asian communities begin to grow.

South Asians on board the Komagata Maru during their ill-fated attempt in 1914 to secure landing rights in Vancouver. Expedition leader Gurdit Singh is at the top left, identifiable by his white beard and light-coloured suit.

Canadian Photo Company, Vancouver Public Library, 136.

The years following the fishermen’s strikes were relatively good ones for BC’s trade union movement. As industry boomed, the working class also expanded. Union membership rose to a record fifteen thousand workers in 175 separate unions. Strikes abounded. When the United Brotherhood of Railway Employees (UBRE) struck in 1903 for union recognition, their walkout for the first time sparked widespread sympathy action by other unions including Vancouver longshoremen, two hundred local teamsters, the BC Steamshipmen’s Society, and the Western Federation of Miners in the Kootenays, who refused to process coal shipments to the CPR. But the familiar litany of an employer importing strikebreakers protected by private security agents prevailed once more. After four months, the UBRE walkout collapsed.

Frank Rogers’s death was front-page news in the Vancouver Daily Province.

Daily Province, April 15, 1903, p. 1.

In the meantime, the strike had also produced BC’s first labour martyr. Frank Rogers, who played such a prominent role in the recent fishing disputes, was felled by a shot fired from the CPR side of the tracks during the UBRE strike, when he approached the docks late at night to see what was going on. He died shorty afterwards in hospital. His rain-soaked funeral procession was the largest union gathering the city had ever seen.

Around the same time, while women workers remained rare outside the canneries in the new century’s first decade, those who did join the workforce showed that they, too, were not always prepared to turn the other cheek. No group carried the torch of female resistance higher than Vancouver’s telephone operators. They were all women, preferred by phone companies because they were considered hard-working and polite to customers. They could also be paid less than men. Local switchboard operators did not accept that view. As early as 1902, they formed a women’s auxiliary of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. Before the end of the year, they were on strike. For the first and only time in more than a century of subsequent labour turmoil, phone service was completely cut off by union job action, prompting another one-and-only occurrence: strike support from a business community desperate to have its phones back in operation.

With pressure from the Board of Trade, solidarity from other trade unions and public sympathy, the phone company caved in. Operators won a wage increase, paid sick leave and, most significantly, a closed shop. Four years later the phone company was ready to counterattack. This time, when telephone workers walked out, the company maintained service with strikebreakers and a few union members who stayed on. The strike collapsed after a few months and the “hello gals,” as they were known, said goodbye to their union. But not forever.

Switchboard operators at the BC Telephone Company in Vancouver, not long after the company broke their union in 1906. They reorganized in 1918.

City of Vancouver Archives, BU P498.

It was tough to sustain a strong labour movement in BC’s ever-cyclical economy so dependent on export markets. Union successes went up and down with the economy. At the same time, employers, government, the hysterical press and hired thugs took turns beating up on unions and workers who dared to stand up and fight for a better life. If they played by the book, they lost. If they took action into their own hands, they lost. Working-class views hardened. The system seemed stacked against them.

For hard-done-by members of the proletariat, the red card of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was a badge of resistance, hidden from employers but waved proudly over a beer. During the first two decades of the twentieth century, no one promoted class struggle more vigorously than the IWW. The “Wobblies,” as members were known, did not achieve the same inroads in BC that they did in the USA, but they certainly made their presence felt for a brief few years. For a time the IWW was the province’s largest union. The Wobblies also staged what was then BC’s biggest strike and were at the centre of one of Vancouver’s fiercest confrontations with civic authorities.

The Wobblies spread to BC after two miners from the Kootenays attended the IWW’s founding convention in 1905 in Chicago. One of them, John H. Riordan, was elected to the national executive and later took a leading role in the union’s shift to greater militancy. The IWW soon chartered half a dozen BC locals including the famous Bows and Arrows Local 526 representing mostly Indigenous lumber handlers on the docks of Vancouver. Except in scattered pockets such as Nelson, which became an IWW stronghold, there was not much Wobbly activity for the next few years. But many travelling and unemployed workers found a home in the union. Its premises in Vancouver served as a mail depot, job mart, reading room, lecture hall, dormitory, and a warm, dry place to chew the fat and share stories of life on the road.

The popularity of the IWW was also indicative of growing resentment of the prominence of the craft unions championed by one-time cigar-maker Samuel Gompers through his American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada. Organized on the basis of specialized trades, craft unions were mostly closed to unskilled and industrial workers. Their approach to trade unionism, political agitation and anything that smacked of socialism was cautious. To many of the workers toiling in factories, mines, the woods and other workplaces where sweat counted for more than the narrow skill of a trade, craft unions seemed part of a labour elite.

These feelings were particularly acute in British Columbia, where even the craft unions tended to be on the left. When Gompers came to Vancouver for a public meeting in 1911, he was shouted down, subjected to what the union leader called “the vilest language I have ever heard.” His raucous reception had been organized by local members of the IWW. The Wobblies argued that only when capitalism and its inherent “wage slavery” were exterminated once and for all could workers share properly in the fruits of their labour.

The IWW’s first big BC confrontation erupted in 1911 in Prince Rupert. The union led several hundred private sewer and road workers out on strike to demand wage parity with civic employees doing the same work. When the contractors imported scabs, the Wobblies organized a day of marches that coaxed many of the scabs off the job. At a site called Kelly’s Cut, however, strikebreakers refused to leave. Rocks were soon flying through the air, first thrown, many believe, by undercover Pinkerton agents who had infiltrated the union. Police and armed citizens counterattacked with clubs and scattered gunfire. One of the strikers was shot in the stomach, another in the shoulder. Many others on both sides were bloodied in the melee, which came to be known as “The Battle of Kelly’s Cut.” Scores of strikers were arrested. Since the local jail had only two cells, union carpenters were summoned to build a makeshift pen to hold all the Wobblies. At least, said a Wobbly wit, it was a union job.

As much a social organization as a union, the Industrial Workers of the World hosted this smoker for Prince Rupert longshoremen at the IWW hall on Christmas night, 1911.

Courtesy ILWU Local 505, Prince Rupert.

Amid the IWW’s sporadic, often spontaneous strikes, nothing came close to matching the scope of the union’s effort to organize thousands of scattered, ill-treated, underpaid railway construction labourers. Most were recent immigrants from Europe, unskilled and with minimal English. They toiled long, back-breaking hours while living in deplorable camps provided by unscrupulous, profit-hungry contractors. No one disputed that their living conditions were a disgrace, not even a shocked parliamentary committee that looked into them. Established unions ignored them as too transient and too difficult to organize. But they were ideal for the Wobblies’ roving activists. The worst conditions existed along the Canadian Northern line. “Words can hardly describe the situation. It is almost beyond imagination,” said one occupant. “The air was so foul at night it was not uncommon for men to arise in the morning too sick to work.”

By 1912, CN labourers were not prepared to take it anymore. All that winter, IWW organizers had been signing them up and laying the groundwork for a strike. As spring approached, they were ready. To the amazement of contractors and other unions, nearly eight thousand railroad construction workers from Hope to Kamloops walked off the job. Although their demands included a nine-hour day and a minimum daily wage of $3, the driving force was the unspeakable state of their overcrowded, filthy work camps.

The Wobblies implemented tight discipline. In Yale, which served as the chief command post, hotels were warned not to serve more than two drinks a day to anyone on strike. Guns and ammunition were banned. To further keep the peace, Wobbly patrols walked the streets, backed up by a “people’s court” that handed out penalties to those who broke the rules. The leadership knew any trace of trouble or unruly behaviour would bring in cops and special constables to break up the strike. The union established its own camps, serving two meals a day. The local constable said he had never seen the town so law abiding. A journalist described Yale as “a miniature republic run on socialist lines, and it must be admitted that so far it has been run successfully.”

A week or so into the strike, legendary Wobbly songwriter Joe Hill showed up. It was his only known visit to BC, attesting to the admiration American Wobblies had for the railroad labourers’ stand. Hill hung around long enough to raise the strikers’ spirits with several on-the-spot songs, including his well-known “Where the Fraser River Flows.” They would certainly have been delighted at such verses as “For these gunny-sack contractors have all been dirty actors,/ And they’re not our benefactors, each fellow worker knows./ So we’ve got to stick together in fine or dirty weather,/ And we will show no white feather, where the Fraser River flows.” The Vancouver Trades and Labor Council, impressed by the IWW’s groundbreaking walkout, rallied to the cause too. They donated money. The British Columbia Federationist, the comprehensive weekly labour newspaper published jointly by the VTLC and the fledgling BC Federation of Labor, became the strike newspaper.

But a fierce counterattack was soon afoot. A month into the strike, hard-line BC Attorney General W.J. Bowser, who had never shown a whit of concern over conditions in the contractors’ camps, dispatched provincial health inspectors to the IWW camps. They were ordered shut for health reasons. When the strikers stayed put, police and contractor goons sworn in as special constables stormed in, ripped down the tents and marched the workers out by gunpoint. Following Bowser’s instructions to “prosecute and imprison on every possible occasion,” hundreds were arrested.

Judge Frederic William Howay demonstrated what BC workers were up against when they dared to challenge the boss. “We are a free and law-abiding people, and above all, we will not tolerate the red flag of anarchy,” he raged at IWW members brought before him. Despite no evidence they had seriously flouted any laws, many were jailed for terms the judge deliberately varied to thwart welcoming demonstrations if workers were released on the same day.

Contractors were bringing in more and more strikebreakers from the United States. The Wobblies responded with an astounding “one-thousand-mile picket line,” which had members picketing employment offices from San Francisco to Seattle to Minnesota to try to stem the flow of scab hires. But they continued to arrive. With newspapers regularly whipping up alarmist flames over non-existent armed strikers and calling for the government to repel the “invasion of the most despicable scum of humanity,” the IWW was beset on all sides. It became impossible to maintain the strike’s original solidarity. The union’s call for mediation was ignored. As fall neared, the strike petered out. A walkout in July by three thousand railroad construction labourers on the Grand Trunk Line up north met a similar fate. Thanks to their fight, however, workers hired back did return to camps that were much improved.

Although occasional strikes and organizing continued in other industries, even as the railway construction boom ended, the IWW was never to come close to the stature it had in BC in 1912. Overall, BC labour conflict peaked that year, with a record 490,726 workdays lost to disputes. The Crowsnest Pass area straddling the Alberta border had been convulsed the year before by an eight-month strike involving nearly seven thousand members of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) who toiled in the region’s deep coal mines, coke ovens and smelters and also worked for the railways. At the end of a historic struggle, the union won a small wage increase but not the union shop requiring all mineworkers to join the UMWA that they had been seeking.

Bobby-like Vancouver police patrol the Powell Street Grounds after charging into a peaceful free-speech rally with clubs and horsewhips to make arrests on Jan. 18, 1912.

Image D-06368, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

For the Wobblies, the tone for 1912 had been set earlier that year with a renowned fight for free speech in Vancouver. One of the union’s most effective recruitment tools was speaking directly to workers from street-corner soapboxes. Outraged by the public airing of such radicalism, civic authorities would usually ban the practice even as they allowed religious street preaching to go on unimpeded. The IWW traditionally answered with a procession of speakers. As each was arrested, another would take his place until city jails and the courts were clogged, driving municipal budgets haywire. More often than not, authorities capitulated.

The battle in Vancouver was more pronounced. Thousands of workers and free-speech supporters were caught up in battle against the city’s newly elected law-and-order mayor James Findlay, who had vowed to crack down on IWW soapbox preaching. In early January, the city banned all outdoor public meetings. Ten Wobblies were arrested for speaking out. The rest of the union movement viewed the arrests as an attack on them all.

On January 28, 1912, at a large protest rally on the Powell Street Grounds (now Oppenheimer Park), prominent labour leader Parm Pettipiece was arrested the moment he began to speak. A large force of waiting police brandishing clubs and horsewhips charged into the crowd. Those unable to flee “went down like ten pins before the irresistible onslaught,” a Province reporter wrote. Thirty protesters were arrested with bail set at a vindictive $500. More street meetings produced more arrests. Someone then had what seemed like a good idea at the time. To subvert the ban, protesters hired a boat and constructed a large megaphone to address crowds at Stanley Park from the water. But strong currents carried the craft off-course and those on board were arrested as soon as they came ashore, their message lost in the blowing wind.

But support for the IWW’s free-speech campaign kept growing. Labour and Socialist Party leaders scheduled another mass rally February 18 at the Powell Street Grounds. They dared city officials to shut it down. Nearly ten thousand people packed the park and adjoining streets to hear a dozen speakers, including several from the IWW. This time, the police stayed away. The crackdown on street meetings eased, and the right to speak freely in parks had been confirmed.

A large group of strikers is arrested near Savona in April 1912 during the battle by IWW railway construction workers against the Canadian Northern Railway. Their only crime seemed to have been their effrontery in going on strike.

Image E-00230, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

The free-speech struggle and the heroic railway strike were high-water marks for the IWW in BC. Once World War I broke out, patriotism trumped the Wobblies’ relentless opposition to the “capitalist war.” Their influence began to wane. The IWW was among those organizations that were banned outright. Every now and then, Wobbly activity would rumble in the lumber camps, but their glory days were done. They left behind a legacy of radical leaders, martyrs and a treasure trove of hard-hitting union songs that are still heard today, including labour’s standard, sung at every convention and picket line: “Solidarity Forever.”

Alone among labour organizations of the time, the IWW saw class as the issue, not race. “When the factory whistle blows, it calls us to work as wage-workers, regardless of the country in which we were born or colour of our skin,” said a Wobbly from Prince Rupert. It was a message that struck home among vast numbers of immigrant and itinerant workers who had been shunned by established unions—and would be again for decades to come. And the IWW’s brand of revolutionary industrial unionism was soon taken up by others.

For the province’s Indigenous people, the early years of the twentieth century were increasingly grim. Smallpox and other fatal diseases had taken a devastating toll. Estimated at seventy thousand strong in 1835, the Indigenous population of British Columbia had fallen to 25,488 in 1901. The Haida Nation was down to fewer than six hundred people. By the time the terrible scourge had run its course, a third of the province’s First Nations had died. “My grandmother told me she lived through it. Not many did,” elder Mary Augusta Tappage recalled in her memoir. “They died like flies.” Smallpox wasn’t the only disease. W̱SÁNEĆ elder Dave Elliott remembered tuberculosis “running like wildfire” through his community. He would wake every morning to the sound of someone “crying or wailing” and the sawing and hammering of casket making.

As well, after many years in which their labour had played a significant role building the BC economy, they were slowly being squeezed out of activities where they had previously flourished. The seal hunt, which brought a measure of wealth for the bold Nuu-chah-nulth sealers on the west coast of Vancouver Island, was banned by all countries in 1911. And BC’s dramatic economic expansion led inevitably to more demand for a stable, year-round workforce. Employers were less willing to tolerate the seasonal employment preferred by most Aboriginal workers, who would often head back to their home villages for traditional dancing, ceremonies and feasting that occupied the winter months.

Government policies were put in place to make it exceedingly difficult for Indigenous workers to share in the economy beyond a subsistence living. These policies were deliberate. Few made it clearer than Premier Richard McBride. When whites in Ootsa Lake, calling themselves the “bona fide” settlers, complained in 1909 that too many Indians were being hired for government road work, McBride replied, “Have issued instructions to our officials [that] white settlers must be considered first.”

Similar anti-Indigenous measures were applied in occupation after occupation. Despite a decline in Indigenous sawmill workers from the days when they were the backbone of the fledgling industry, hand-logging had continued to be a major source of income for coastal First Nations. They would take their saws, axes and other tools into the woods to harvest timber. In 1904, however, the province unleashed a major giveaway of accessible forest land while cracking down on hand-logging without a licence. Most licences went to non-Indigenous people, freezing out Indigenous loggers. Rubbing salt into the wound, the province prevented Indigenous people from logging without permission even on their own reserves.

At the same time, Indigenous people also lost the right to hunt whenever they wanted. They were now confined to specific seasons set by BC game wardens hostile to First Nations hunters. There was no need for Aboriginal people to hunt deer out of season in the fall, the province’s game warden told a Royal Commission in 1913: “In many places there is work for Indians haying and harvesting. Giving Indians permits to hunt deer at this time of year simply encourages them to do nothing else.”

There were pockets—such as the Vancouver docks, the northern fishing and canning industry, and Fraser Valley hop fields—where Indigenous labourers remained a significant part of the workforce. But new fishing restrictions were another hardship. Upstream fishing weirs, traps and reef nets that Indigenous fishers had used for centuries to catch returning salmon were banned. Indigenous people were prohibited from selling salmon caught during their food fisheries, which were heavily regulated as well. And the large majority of commercial fishing licences were now issued to individuals rather than through canneries; Indigenous fishermen found it hard to acquire these licences, granted almost willy-nilly to whites and Nikkei. Noting the bewildering array of regulations that governed their once untrammelled right to hunt and fish, elder Peter Webster lamented, “All of these things made it easy to get into trouble with the law. I think a lot of us became ‘criminals’ without really knowing the reason.”

A traditional Indigenous salmon weir across the Cowichan River in the late 1860s. They were later banned as part of a deliberate strategy to drastically reduce the Indigenous share of salmon they once had all to themselves.

Image C-09260, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

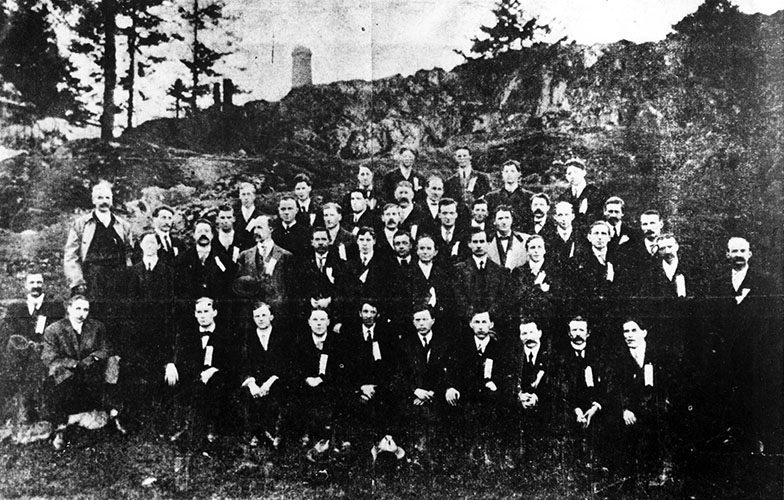

Ironically, amid all the division, there was a consistent call by union leaders during the first decade of the new century for greater unity to confront the forces of capitalism. On May 2, 1910, twenty-six delegates met in Vancouver to form labourers’ first province-wide organization, the BC Federation of Labor. Although the Federation would have several reincarnations in the years ahead, it was radical from the start. Pledging itself to unceasing struggle for the eight-hour day, the new organization declared that the future belonged “to the only useful people in human society—the working class.” Unions rushed to join. Within a year, it was able to take a 50 percent interest in the VTLC’s labour newspaper, The Western Wage Earner, and rename it The British Columbia Federationist, which became one of the most comprehensive labour publications in North America.

Delegates and officers of the BC Federation of Labor’s historic first convention at the Labor Hall in Victoria, March 13-15, 1911.

UBC Rare Books and Special Collections, 1429-1.