4 The Great Vancouver Island Coal Strike

Vancouver Island coal miners had not lost their burning sense of injustice over their treatment by the Dunsmuirs. Their deep-seated hostility had been further powered by another dreadful gas explosion, this one south of Nanaimo at Extension in 1909. The tragedy claimed thirty-two lives. One miner’s wife remembered bitterly, “You don’t forget when you see thirty graves, all new, dug in a row waiting to be filled with men you’ve known all your life.”

Despite their past defeats, many felt the time was right to take on the owners yet again. In 1911, the miners had called in the tough, seasoned United Mine Workers of America in hopes of triumphing at last in their long fight for union recognition. Hundreds flocked to join. With antagonism toward the company sky-high, the stage was set for the Great Vancouver Island Coal Strike. Lasting just short of two years, the confrontation turned into the most protracted, fiercely fought labour dispute in the province’s history. It was bare-knuckled class warfare of the old school, with neither side willing to give an inch. It all began with a member of the miners’ safety committee named Oscar Mottishaw.

In June 1912, Mottishaw reported gas in one of the shafts at the deadly Extension mine. By then, James Dunsmuir’s coal-mining operations had been bought out by Canadian Collieries, a conglomerate dominated by the Canadian Northern Railway. But there was no shift in the company’s ruthless anti-unionism. Although a mines inspector confirmed Mottishaw’s report, the veteran union man was soon out of work. Shortly after he hired on in September as mule driver for a contractor at the company’s mine in Cumberland, Mottishaw was sent packing once more. This dismissal ignited the strike.

While seemingly a trivial matter to set off such a reaction, his firing underscored two issues Island coal miners had been fighting for since they first rose up against the Dunsmuirs in 1870: mine safety and the right to join a union without being blacklisted. On September 16, miners at Cumberland and Extension called a one-day “holiday” to demand Mottishaw’s reinstatement. The company told them not to bother coming back. Within three days, sixteen hundred Canadian Collieries workers were off the job and the war was on.

The owners quickly unleashed the tried-and-true tactics of the Dunsmuirs. Miners in Cumberland were evicted from their company-owned homes, forcing families into crude tents. Chinese miners initially stayed out too. Faced with threats that they too would be thrown out of their homes and already ostracized by the strikers, they soon went back to work. Strikebreakers were also brought in along with special constables to protect them. As usual, the government knew which side it was on. Brushing off entreaties from union and socialist MLAs to intervene, Premier Richard McBride told a confidant he believed it “intolerable” for coal miners to make demands of the mine owners.

Arriving strikebreakers were greeted by raucous protest parades, and were further harassed on their way to work by loud, discordant music and relentless heckling. Strike pay was $4 a week with extra money for wives and children. A multitude of activities were organized to keep the restless strikers out of the saloons as much as possible. In Ladysmith, where most Extension miners lived, the union rented a large hall with games rooms, a library and a piano for regular concerts. There were sports days, and at Christmas the hall hosted a large, festive gala with music and dancing to the wee hours for the adults and toys, candies, clothes and oranges for the children. Premier McBride donated the grand sum of $10 to the miners’ Christmas fund to show what a merry old soul was he.

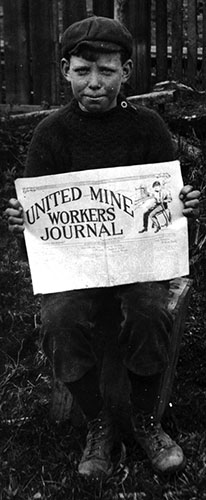

A small boy holding a union newspaper near the beginning of the coal strike in 1912.

Cumberland Museum and Archives, C110-128.

Wives, daughters and sisters turned the Women’s Auxiliary into a formidable force. They raised money, staged support marches and social events, and harassed authorities and strikebreakers. Two fiery women were fined $20 by the courts for persistently calling the pit bosses “scabs.” Many women also took on work outside the home to help their families survive. Their strong backing of the strike, accompanied by growing agitation for women’s suffrage, was critical to keep the union pot boiling. After eight months, however, with no budge from the mine owners, matters were becoming desperate. Staffed by Chinese labour and other strikebreakers from as far away as Italy, the Cumberland mine was back to normal production. The mines at Extension were running too, albeit with limited production. The union decided it had to expand the strike.

On May Day 1913, thousands of miners, their families and union supporters converged on Ladysmith for the largest parade and display of community solidarity the Island had ever seen. A brass band led the way. Children marched behind a banner proclaiming themselves “The Hope of the Future,” while miners and their wives followed with defiant banners declaring “In Union There Is Strength” and “Workers of the World Unite.” The day culminated that evening in Nanaimo. A thousand miners packed the town’s Princess Theatre for a tumultuous meeting that endorsed the union’s decision to broaden the strike to all three Nanaimo-area mines: Western Fuel, Pacific Coast Coal Colliery and the small Jingle Pot mine. The next day, thirty-seven hundred miners were off the job from Cumberland to Nanaimo.

Miners’ wives and children parade behind the union’s brass band as part of a mass procession down the main street of Ladysmith in 1913 during the Great Coal Strike of 1912–14. Their support was crucial to maintaining the long, difficult dispute.

Image E-02631, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

Yet more and more strikebreakers arrived. After eleven months on strike and determined to take on the scabs in pitched battle, the miners finally snapped. The turbulence began in Nanaimo when a large crowd of miners and their families swarmed the pitheads to dissuade strikebreakers from going to work. Several were injured in the scuffles that broke out. The next day at Pacific Coast’s South Wellington coal mine, hundreds of miners drove strikebreakers and their families out of town and into the woods. On their way back, they attacked company property and the bunkhouses of Chinese workers.

On the night of August 13, jeering strikers massed outside the Temperance Hotel in Ladysmith, where a number of scabs were staying. When police arrested one of them for singing, “Hurray, hurray, we’ll drive the scabs away,” the crowd hurled rocks through windows of the hotel and houses belonging to strikebreakers and mine supervisors. A short time later, someone tossed a small stick of dynamite into the bedroom of strikebreaker Alex McKinnon, where his five children were sleeping.

As McKinnon rushed to toss it outside, the dynamite exploded, blowing off his right hand and burning his face. (It emerged later that the culprits were not strikers but three non-union local men caught up in events after more than a few swigs of the bottle.) Miners also ransacked Ladysmith’s Chinatown, ordering its residents to get out of town. Crowds continued to surge through the streets all night and into the next day, prompting the mayor to call for the militia.

Back in Nanaimo, strikers forced the steamer Princess Patricia to return to Vancouver with its human cargo of strikebreakers and twenty-five special constables. Feelings reached a fever pitch on a false report that strikebreakers had shot and killed six strikers in Extension. Miners rushed to the scene. A tense standoff followed between strikebreakers holed up in a mine pithead and union men massed outside. Shots were fired at the strikers. Some strikebreakers retreated down the tunnel while others snuck away into the surrounding forest. Miners headed into the village when darkness fell, plundering and burning homes owned by the company, scabs and Chinese immigrants.

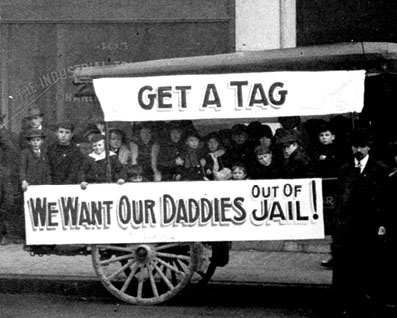

After the mass arrests of striking Vancouver Island coal miners, an outpouring of support came from the BC labour movement, particularly in Vancouver. This fundraising tag day outside the city’s Labor Temple on Dec. 20, 1913, was organized by the hastily formed BC Miners’ Liberation League.

City of Vancouver Archives, 259-1.

This mounted Maxim machine gun was part of the force brought in by the militia against unarmed striking coal miners after trouble flared in August 1913, one year into their strike. The gun was manned by members of the Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery.

Image A-03159, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

Once this violent outburst was out of their systems, strikers resumed peaceful picketing. That didn’t matter to Attorney General William Bowser, who immediately ordered in the militia complete with a pair of mounted Maxim machine guns. The deployment of the militia actually re-energized the miners, attracting an outpouring of support from the public and other unions. In a rhetorical outburst, BC Federation of Labor vice-president Jack Kavanagh told a large rally in Vancouver that mining communities were being “terrorized by half-clad barbarians armed with rifles and bayonets … No reptile ever evolved from the slime of ages resembles the spawn of filth now on Vancouver Island known as the militia.”

The speedy crackdown on those suspected of fomenting trouble during the few days of violence was harsh. At Nanaimo’s Athletic Hall, bayonet-wielding soldiers stormed into a meeting of more than a thousand miners and ordered everyone out. To ensure no one escaped out the back, the rear door was guarded by one of the Maxim machine guns. A number of union leaders and ordinary miners were marched off to jail while soldiers ransacked the empty hall for weapons. They found none. Similar roundups took place in Ladysmith and Extension. All told, 213 strikers were arrested, charged with such offences as assault, obstruction of police, unlawful assembly and the heinous crime of picketing. Most were held without bail until their trials. In Ladysmith, Judge Frederic Howay imposed sentences that were severe even for those law-and-order times. Five men got two-year sentences, twenty-three received a year and many others three months in jail. When dozens of the prisoners returned from Oakalla prison to Ladysmith the next spring, they were joyfully paraded through the streets to a loud rendition of “La Marseillaise.”

Striking Ladysmith coal miners are marched off to jail by armed soldiers with bayonets fixed in place. Although some faced assault charges, most were charged only with unlawful assembly and picketing. All were held without bail until their trials. Many received prison sentences.

Image E-01194, Royal BC Museum and Archives.

Striker Joseph Mairs was not among them. Tragically, he died in Oakalla two weeks short of his twenty-second birthday, a victim of poor medical treatment after he fell ill. A funeral procession reportedly nearly a mile long accompanied his body to the Ladysmith cemetery, where he joined those killed in the Extension mine explosion of 1909. A large memorial commemorating Mairs still dominates the cemetery today. Part of the inscription reads, “A martyr to a noble cause—the emancipation of his fellow men.”

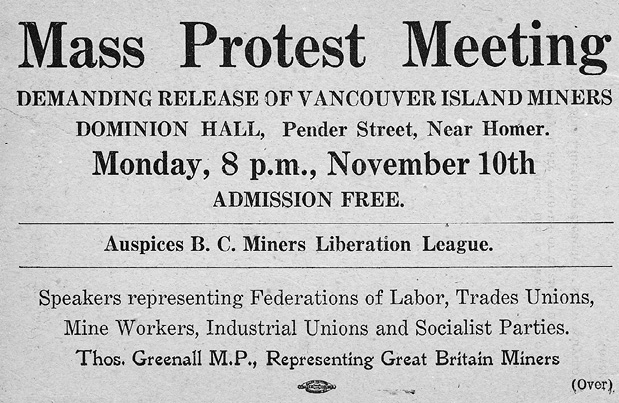

In spite of all their setbacks, the miners’ spirits remained strong even as the strike entered its second year. Sending in the militia was widely regarded as a declaration of war by workers throughout the province. That November, unions and left-wing organizations joined together to form the BC Miners’ Liberation League. Its elected president was a prominent member of the IWW. The League dedicated itself to raising money and public support for its beleaguered brothers on the Island and the release of those in jail. Public pressure grew for a fair deal to end the strike. Even McBride weighed in.

But the coal companies, by then enjoying near normal production, saw no need to bend. A visit in June by the famous American union firebrand Mother Jones briefly buoyed the miners. Local historian John R. Hinde speculates that her scorching rhetoric may have motivated their rejection of a status quo offer by the companies. Still, as the months continued to roll by, nothing could change the bleakness of the miners’ situation. The gathering war clouds in Europe doomed the Liberation League’s agitation for a forty-eight-hour general strike to back the miners, and the union began to run out of money. In July the UMWA local made a painful decision to cut off strike pay. A month later, two weeks after the outbreak of World War I, miners voted to return to work after twenty-three months of heroic struggle that remain unrivalled in the annals of BC labour.

Young cyclist and coal miner Joseph Mairs died in Oakalla prison in early 1914, three months into a harsh sixteen-month sentence for activities during the coal miners’ strike. This postcard was sold to raise funds for a large memorial headstone in the Ladysmith cemetery, saluting Mairs as a martyr to a noble cause.

Courtesy David Yorke.

A postcard for the public meeting organized by the BC Miners’ Liberation League to demand the release of arrested Vancouver Island coal miners. A featured speaker was British coal mining trade unionist and Labour Party politician Thomas Greenall.

Courtesy David Yorke.

The visit in 1914 to Vancouver Island by the famous “friend of the miners” made The New York Times.