21 Picking on the Public Sector

The BC Liberals who took over government from the NDP had little in common with their federal Liberal namesakes. They were a centre-right coalition united, like the BC Social Credit Party, by a common desire to keep the NDP in opposition and promote free enterprise. Their leader Gordon Campbell, a three-term mayor of Vancouver, was committed to dramatically lowering taxes and significantly reducing government.

During the 1996 election campaign, which he had lost to Glen Clark, Campbell had vowed to scrap the Health Labour Accord, the landmark deal between the NDP and health unions to protect jobs during hospital downsizing. But just before the 2001 campaign, he surprisingly reversed himself. Asked point-blank by HEU communications director Stephen Howard whether he still wanted the accord gone, Campbell replied, “I don’t believe in ripping up agreements. I said I disagreed with [it]. That’s just the way it was. I am not tearing up any agreements.”

Then, shortly after taking office, the Liberals did precisely what Gordon Campbell had promised they would not do. Without the slightest notice to the union, the Liberal government rammed through legislation stripping key contracting-out protections from the Hospital Employees’ Union’s collective agreement. Hospitals were now free to contract out and privatize the jobs of thousands of hospital employees. More than 80 percent of the positions affected were held by women. They included many women of colour, older women and immigrants. When the premier and his government had finished using their massive majority to enact Bill 29 just before dawn on January 28, 2002, the HEU’s contract lay in tatters.

Gone was the celebrated Health Accord, including the Health Labour Adjustment Agency, which had done such an efficient job of retraining laid-off workers for positions elsewhere in the system. Gone were seniority bumping rights dating back to the days of W.A.C. Bennett. And gone too were restrictions against contracting out that were first negotiated under Bennett’s son Bill. It was, said The Globe and Mail, an act of “legislative vandalism.” Hospitals wasted little time taking advantage of the opportunity to ditch the union and contract out services. Almost overnight, in Vancouver and the Fraser Valley, long-term service contracts were signed with multinational corporations who made their large profits by squeezing workers.

Laundry, dietary and housekeeping employees who had been earning $18 an hour found themselves on the street. If they wanted to keep working, they were forced to reapply for their old jobs, now non-union and paying about $10 an hour, with no guarantee they would be hired. The hospitals were cheered on by health minister Colin Hansen and other ministers who said there was no justification for paying hospital support workers $18 an hour. Ten dollars an hour was fine.

At the same time, the government began closing long-term care facilities, where staff knew and cared for the residents, forcing seniors into a vaguely defined future of assisted-living facilities where demand exceeded supply. Heart-wrenching stories filled the media about couples married for decades being separated by the transition. The Liberals’ pre-election promise to create fifty-five hundred more long-term care beds proved as hollow as Gordon Campbell’s pledge not to rip up agreements. Not even the venerable May Bennett Home in Kelowna, named after the wife and mother of BC’s two Bennett premiers escaped the chopping block. Meanwhile, HEU members at the long-term care homes were losing their jobs.

Community pressure sometimes stalled the process, and occasionally there was a change of heart. But mostly the closures rolled forward. Province columnist Mike Smyth observed, acidly, “This government is desperate to kick old people out of nursing homes to save money.”

HEU members fought back against the loss of unionized laundry, kitchen and housekeeping services to low-paying, non-union private corporations with protests, short-term occupations, picketing and large, spirited rallies. Secretary-business manager Chris Allnutt, president Fred Muzin and financial secretary Mary LaPlante were arrested for taking part in a union blockade that put bales of hay across the road at a Chilliwack industrial park where trucks full of dirty laundry were scheduled to roll to Calgary. Given a ten-year private contract to provide clean laundry for four Fraser Valley hospitals with no local facility, K-Bro Linen Systems had to truck millions of tons of laundry hundreds of kilometres to Calgary and back, taking forty-three local union jobs with them.

The BC Children and Women’s Hospital in Vancouver was so anxious to shed union jobs that they awarded a housekeeping contract to an American company owned by Cecilia von Dehn, an ardent anti-abortionist with a long history of harassing abortion clinics. Fine, except that abortions were performed at the hospital. After a public outcry, health minister Colin Hansen admitted due diligence had not been done. The contract was cancelled with ninety days’ notice. Until then, extra security was hired to ensure the safety of women seeking abortions and of staff.

Over time, an estimated eight thousand HEU members would be bumped from their jobs by private non-union contractors. It was the most extensive privatization of health services in Canada and, some said, the largest mass layoff of women workers since the end of World War II. In a controversial effort to ease the bleeding, HEU leaders worked out a tentative deal to accept major mid-contract concessions, including deferment of scheduled 4.4 percent wage increases, lengthening the workweek to 37.5 hours with no hike in pay (effectively, a 4 percent pay cut), and a two-year extension of the current contract to 2006. In return for these payroll savings of $500 million, health employers agreed to better severance and bumping rights for laid-off workers and to cap the number of contracted-out jobs at a still substantial thirty-five hundred full-time positions. This was nevertheless a big improvement over the government’s original target of twenty thousand jobs, according to union leader Allnutt.

When the Gordon Campbell government broke its pre-election promise and unilaterally stripped contracting-out protection from members of the Hospital Employees’ Union in 2002, thousands of hospital laundry, dietary and housekeeping employees lost their decently paid union jobs. Many of them were immigrants.

Hospital Employees’ Union.

But he was unable to sell the so-called Framework Agreement. Members unaffected by contracting out were less than thrilled by the prospect of working longer hours for less pay. Others felt the union was giving up too much for too little. The package was voted down by 57 percent. In the meantime, a little-noticed constitutional challenge to Bill 29 by the HEU and allied health unions was beginning to wind its way through the courts. The unions argued that the unilateral removal of contract provisions by the government violated their right to freedom of association guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The BC Supreme Court dismissed the unions’ case, as did the BC Court of Appeal. Without a lot of hope, the unions appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada.

After the collapse of the Framework Agreement, the pace of layoffs quickened. The largest privatization took place at Vancouver General Hospital, where 950 union housekeeping positions disappeared, replaced by a now familiar contingent of low-paid, non-union employees hired by the US-based multinational Aramark Corp. By the time bargaining for a new HEU contract reached a head in the spring of 2004, twenty-five hundred more members had been shown the door. Among them was Deanna Graham. In an emotional letter to the HEU’s Guardian periodical, the veteran cleaner at Vancouver General decried her fate: “Despite popular opinion, I do not believe eighteen dollars an hour is substantial after twenty-five years of labour. $9.50 an hour is not only insulting, but impossible to raise a family on.” Bill 29 did more than strip away their contract rights, she said. “It attacked our very identity. I am not an overpaid cleaning lady pushing a broom. I am a dedicated employee, a team player, a loving mother, and a compassionate human being.”

At the bargaining table, the HEU offered wage rollbacks similar to those in the Framework Agreement, but with better security, bumping rights and severance pay. When employers responded with demands for even more concessions, union members’ frustration and rage boiled over. Following a massive 89 percent strike vote, picket lines went up at hospitals across the province on April 25. Three days later, the government brought in back-to-work legislation. Passed at six o’clock the next morning, Bill 37 imposed a two-year contract on the hospital workers and ordered an end to their strike.

In 2004, the BC Liberals’ back-to-work legislation and two-year contract imposed on striking members of the Hospital Employees’ Union, already devastated by government-sanctioned contracting out of thousands of their jobs, prompted threats of a general strike and the largest May Day march in Vancouver in years.

Kim Stallknecht photo, Province newspaper.

Its terms might have been drawn up by Ebenezer Scrooge. Union members were thumped with a wage cut of 11 percent plus a longer workweek, amounting to another 4.4 percent reduction in their hourly rate. There was no cap on layoffs, no provisions for severance pay. To rub more salt into the wounds, the wage rollbacks were retroactive to April 1, meaning members would owe the government money on their return to work.

The HEU instructed its members to maintain their picket lines. Outside Vancouver General, Allnutt told cheering strikers, “We undertake this because the government has introduced legislation that is unprecedented, is draconian, and is taking away the fundamental freedoms and rights that we have in a free and democratic society.” Geraldine Ross, a sixty-two-year-old unit clerk at Women’s Hospital, said Bill 37 would cut her wages by $3.50 an hour with no job security. When a manager tried to serve her with a warning of disciplinary action, she turned her back. “We consider ourselves part of the health-care team,” Ross told a Vancouver Sun reporter. “What we get paid, we earn. This legislation is demeaning. It’s like a kick in the stomach.”

The harshness of the legislation and the HEU’s decision to defy it spurred spontaneous outbreaks of industrial action. As the weekend approached, thousands of CUPE members walked out, shutting down municipal, school and library services around the province. “The government stepped over the line, and it’s time we stand up for what we believe in,” said Vancouver garbage collector Doug McNicol. Some sawmills, a pulp mill, a power-generating plant and scattered transit services were also struck. The BC Federation of Labour was swamped by phone calls from other unions clamouring to join in.

The result was a hastily cobbled-together action plan leaked to BCTV’s Keith Baldrey and the Vancouver Sun that threatened mass walkouts of public- and private-sector workers in the week ahead. Emblazoned across the top of the Sun’s Saturday edition was the headline, “Blueprint for havoc.” For the first time since the days of Operation Solidarity more than twenty years earlier, the province was facing the spectre of a general strike. Saturday was also May Day. The pending confrontation produced the largest, most spirited “workers’ day” rallies in years. Trade unionists were fired up and ready to go.

Not for the first time, the threat of a wide-scale, militant labour response, coupled with pressure from a worried BC Employers’ Council, tempered the BC government’s previously inflexible approach. On Sunday, last-ditch talks took place to try to settle the bitter dispute before Monday’s D-Day. Adding to the urgency for the union was a rare Sunday decision by the BC Supreme Court finding the HEU guilty of contempt of court for defying the back-to-work order. The court threatened the union with punitive fines if its members remained off the job.

Shortly before midnight, Allnutt and BC Federation of Labour president Jim Sinclair announced that the union had a deal. The government agreed to cap the number of layoffs at six hundred over the next two years, eliminate employee paybacks by moving the effective contract date up to May 1, and provide a new $25 million severance fund for those let go. Given the uncertainties of waging an all-out illegal strike, the two union leaders decided these improvements over Bill 37 were enough. With less than nine hours to go, the solidarity walkouts, along with the strike, were called off. “This was the best we could achieve,” said Allnutt. “We were faced with a law and a government determined to privatize health care. We have limited that, and that is a victory for working people and patients in this province.”

But the abrupt end to a swelling protest movement, when emotions had been building all weekend in anticipation of Monday’s “big bang,” angered some HEU members, who were particularly furious that the settlement left their pay cut and longer workweek intact. “I feel betrayed,” said medical lab technician Susan Barron, sobbing bitterly as she returned to work. “We’ve been sold out by the government and our leaders.” At Royal Jubilee Hospital in Victoria, single mother Jade Cabico collapsed into the arms of a colleague, venting her anguish at the settlement and the likelihood of losing her job in the fall. “I’m not going to go begging for my job back. I give up. I’m sick of it.”

Dissident pickets closed HEU offices for the day, while protest lines at some hospitals stayed up well into the afternoon. Six weeks later, for the union’s several days’ defiance of the back-to-work order, Supreme Court Justice Robert Bauman fined the HEU $150,000, then the largest fine imposed on a union in BC history. Not long afterward, Chris Allnutt was replaced by Judy Darcy, who had moved to BC after twelve years at the national helm of CUPE, the largest union in Canada. Darcy restored calm and unity to the fractured labour organization.

A feature of the HEU’s resistance had been strong community support, even in Liberal-leaning areas like the Cariboo. Diana French, a columnist for the Williams Lake Tribune, touched on why. “In a small community like ours,” she wrote, “the HEU workers aren’t the faceless ‘unskilled, overpaid workers’ the government wants us to believe they are. Most of us know them as good, decent, caring and hard-working citizens. They are our friends, our relatives, our neighbours.”

In Quesnel, one hundred kilometres farther north, as many as five thousand people walked out on Monday, despite the settlement. Schools, mills, government offices, non-essential hospital services and even major grocery stores were affected. “We’re just sick of the government,” explained local CUPE president Dan Weiman. Local teachers’ union president Brian Kennelly said Quesnel had been hit hard under the BC Liberals. “We’ve lost social workers, forestry workers, highways people, hospital workers,” said Kennelly. “We’re losing jobs, we’re losing families. There are empty houses. We even lost our Zellers store.”

The HEU set about organizing the thousands of non-union workers hired by the multinational corporations. It was not easy. The corporations filed countless complaints to the LRB. The union and privatized workers also had to battle against owners like those at Nanaimo Seniors Village. Whenever its employees organized, the owners ended their contract. Care aide Sheil Niehaus told a reporter she had suffered three firings in four years. Each time, she was hired back to do the same job for a different contractor for less money. In the Lower Mainland, 450 health aides employed by private contractors were dismissed after they joined the HEU and won higher wages. But the union persevered.

For four days, members of the Hospital Employees’ Union thumbed their noses at the government’s harsh contract and back-to-work order (Bill 37) passed on April 28, 2004, with escalating support from the rest of the trade union movement, before the union reached a settlement just hours before a wealth of further solidarity walkouts were to take place.

Hospital Employees’ Union.

When certification votes were eventually tallied, the HEU won almost all by lopsided margins. Hard bargaining, including a brave, seven-week strike by fourteen hundred dietary, cleaning and other support staff against the French multinational Sodexo nudged wages over $13 an hour, $3 more than most workers had been earning. Ten years later the HEU represented the vast majority of hospital employees working for the big four corporations: Sodexo, Aramark, Axiona and Compass. Succeeding rounds of negotiations managed to raise wages up to $16 an hour with significantly improved benefits.

Although it was the main government target, the HEU wasn’t the only victim of Bill 29. Unionized community social services workers were also swept into the Health and Social Services Delivery Improvement Act, a euphemism of the first order. With memories still fresh of their long strike during the last term of the NDP, they found their hard-won contract gains wiped out, their job security imperilled and their union successorship rights cancelled. And the province’s teachers had their own union-busting act to contend with.

Throughout the first fifteen years of Liberal government, no union was targeted more than the BC Teachers’ Federation. At times, especially during Christy Clark’s time as education minister during the early years of the Campbell administration, it appeared almost personal. Just months after chalking up their massive majority against the dispirited NDP, the Campbell government had proclaimed education an essential service, making it difficult for teachers to launch an effective legal strike. Teachers retaliated by refusing all voluntary administrative and supervisory duties.

The government did not take long to strike back. In late January 2002, at the same time Bill 29 came down the pike, the teachers were hit by Bills 27 and 28. The first imposed a three-year contract, providing minimal annual increases of 2.5 percent. But that was a mere glancing blow compared to the knockout punch delivered by the Public Education Flexibility and Choice Act (Bill 28), surely labelled by someone with a macabre sense of humour. As they had with health-care unions and community services workers, the government stripped key rights from the teachers’ existing contract with no notice or attempt to negotiate.

The teachers lost negotiated limits on class size, stipulations on class composition, support for students with special needs and staffing ratios for librarians, counsellors and ESL instructors, plus the right to negotiate them at all. If that were not galling enough, these were rights the teachers had won under the NDP by accepting a virtual wage freeze in their last agreement. Now they were without both the improved working conditions and the money they surrendered to achieve them.

In just a few days, the government had wiped out the work and struggle of a generation of teachers—many of whom had gone on strike to win similar conditions when there was local bargaining with individual school boards. Their fight to regain them would be prolonged and arduous. For the next decade and a half, there was no more persistent adversary of the Liberal government than the BCTF and its tenacious membership. And in the end there would be the best of victories.

The day Bill 28 became law, teachers walked off the job for a one-day protest. At a pumped, packed rally at the PNE Agrodome, BCTF president David Chudnovsky told thousands of cheering teachers, “This is not a one-day protest. This is day one of the protest.” Rather than charging out on an illegal strike, however, the BCTF opted to bide its time and prepare for the long haul. Membership meetings provided information and gathered feedback. Dues money financed a Public Education Advocacy Fund. The BCTF joined the BC Federation of Labour in 2003 and the Canadian Labour Congress two years later. The organization also launched an expensive but effective public information blitz during the run-up to the 2005 provincial election, highlighting the impact of school closures, teacher layoffs and funding restrictions in other areas. And the teachers initiated a constitutional challenge to Bill 28 as other unions did with Bill 29.

Teachers had also been flexing their muscles elsewhere. When CUPE support workers in twenty-nine school districts went on strike in 2000, nearly every teacher honoured their picket lines. In 2003, when education minister Christy Clark provocatively took steps to remove teachers’ control of the professional College of Teachers, BCTF members refused to pay their College fees. The government backed down.

By the time talks for a new contract fell apart in the fall of 2005, teachers were primed to take the government on, hardened by the treatment they had received over the previous four years. The BCTF began job action with a ban on administrative duties. That was to be followed by rotating district walkouts and a full-scale strike October 24.

They didn’t have to wait that long. In early October, for the second time in less than four years, the Liberals foisted a collective agreement on the teachers. Following the pattern of other public-sector contracts, Bill 12 froze their wages for two years while providing nothing in better classroom working conditions.

Furious at the government’s sledgehammer, teachers crowded hastily arranged membership meetings across BC. After careful warnings about the implications of illegal job action, members voted overwhelmingly to defy Bill 12 and go on strike. The 90.5 percent vote was higher than the first strike vote. A pre-emptory ruling by the BC Labour Relations Board that a strike would be illegal and the filing of a back-to-work order in BC’s Supreme Court were ignored. Teacher picket lines went up on Friday, October 7, just before the Thanksgiving weekend.

At the helm of the defiance was the BCTF’s fifty-three-year-old president, Jinny Sims. Born in a tiny village in the Punjab region of India, Sims was the first woman of colour to head a major union in BC. After her family emigrated to England, she was a good student, a community activist and an athlete, winning medals in fencing and a black belt in judo. Sims took up teaching. But the policies of then education minister Margaret Thatcher prompted Sims and her husband, also a teacher, to try Canada. The couple wound up in Nanaimo in 1977, where Sims established her career as a high school teacher and counsellor.

Sims was spurred to become active in the BCTF by the anti-teacher actions of the Vander Zalm government, dubbed “Vanderlism” on thousands of political buttons. In a few years, she was local president, tearing up her NDP membership card after the Harcourt government imposed province-wide bargaining. “They decertified seventy local unions with a stroke of the pen,” said Sims, still angry more than twenty years later. (Sims later rejoined the party, serving as an NDP MP in Ottawa and winning a seat for the NDP in the 2017 provincial election.) Gradually, she worked her way up BCTF leadership ranks until her election as president in 2004.

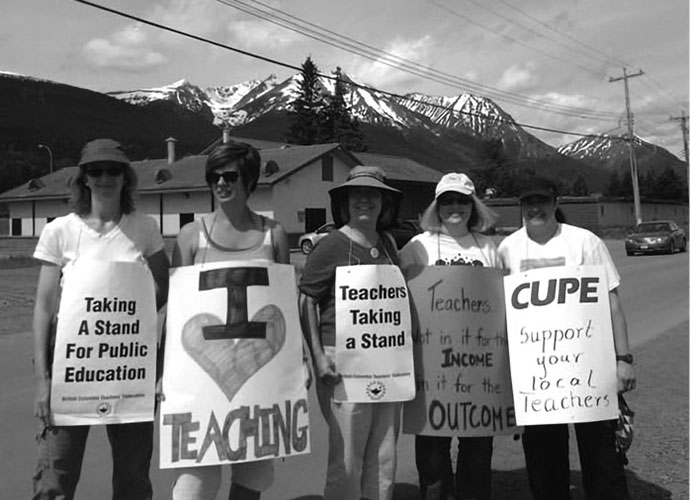

The teachers’ 2005 illegal strike was solidly supported by its members throughout the province, including this spirited group of teachers in the Bulkley Valley taking advantage of some rare October shirt-sleeve weather up north. CUPE school board workers joined them on the picket line.

Courtesy BCTF.

As such, she found herself the public face and leader of a province-wide illegal strike by thirty-eight thousand teachers. The stakes were upped right away. In the midst of the holiday weekend, BC Supreme Court Justice Brenda Brown found the BCTF guilty of contempt of court for defying the back-to-work order. If citizens could choose which court orders to obey and which to flout, “anarchy cannot be far behind,” Justice Brown intoned. She put off penalties for the teachers until Thursday. “My mother was petrified I was going to be in jail,” Sims recalled.

But there was no weakening of resolve. “We are taking a stand against the unjust and punitive legislation of this government,” Sims maintained. “Sometimes a law is bad and we as citizens have to take a stand.” While the media and cabinet ministers thundered about the bad example teachers were showing their students by disobeying the law, polls showed a majority of the public supported them. This remained true throughout the strike, confounding the Liberals, who expected an anti-teacher public backlash.

On Thursday, October 13, BCTF leaders sat tensely in BC Supreme Court waiting for Justice Brown to hand down her punishment for their ongoing contempt of court. Instead, to their amazement, the judge moved against the BCTF’s strike fund. She froze the organization’s accounts, forbidding strike pay or any other financial assistance to teachers on the picket line. It was a continuation of Justice Brown’s surprising reluctance to fine or imprison union leaders while the dispute lasted. It was as if she were giving a signal to the parties to settle it themselves. Most teachers took the cut in stride. “This isn’t about wages or strike pay,” said French immersion teacher Erin Fitzpatrick. “If I wanted money, I wouldn’t be a teacher.” As the rain poured down outside her East Vancouver school, Grade 4 teacher Sylvia Seto echoed, “Fifty dollars a day [strike pay] is not what it is all about. We are here for public education and for the benefit of our province.”

BC teachers take their cause to the steps of the provincial legislature in Victoria during their 2005 strike that defied a back-to-work order for nearly two weeks.

Joshua Berson photo.

For some, however, losing their strike pay after a wageless summer was a monetary blow. But the judge’s unusual order prompted an outpouring of support from other unions and members of the public. So much donated food showed up on the picket line that some teachers reported gaining weight. In Dawson Creek, there was dismay when it seemed the local Tim Horton’s had run short of donuts, a staple of the picket line. It turned out a local car dealership had bought up most of the supply to distribute to the picketers themselves. In affluent West Vancouver, chauffeurs were reportedly delivering trays of catered hot food to the line. College faculty associations handed out $50 food vouchers, and a much-appreciated Hardship Fund was set up by the Canadian Teachers’ Federation for those in need.

The next day, a week into the strike, organized labour threw its collective weight behind the striking teachers. Flanked by fourteen union leaders, BC Federation of Labour president Jim Sinclair announced that other unions would walk off the job Monday, October 17, in Victoria for a mass protest on the lawn of the legislature. If the government maintained its steadfast refusal to talk with the teachers as long they continued their illegal strike, he vowed further action.

Withstanding a drenching rain, more than twelve thousand people rallied in front of the legislature on the big day. Much of Victoria was shut down. CUPE went even further, calling fifteen thousand members off the job on Vancouver Island and four thousand the following day in the north. Maple Ridge teacher Mary Johnston woke at 4 a.m. to board a crack-of-dawn bus to the rally. “We don’t feel like we’re breaking the law, because it’s a bad law,” she told a reporter. Premier Campbell’s plea to obey the law was ridiculed by signs displaying the premier’s mug shot from his well-known drunk-driving escapade in Hawaii. “This is what illegal looks like,” said one. A second sign read, “Bill 12, another example of impaired judgement.”

In an uncompromising speech, Jinny Sims told Campbell to call off his threats. “Stop trying to divide us. It will not work. We will not be broken!” She defended the illegal walkout as civil disobedience. “There is a big difference between breaking a law and having a law created to break you,” she told the energized crowd. Another sympathy strike was scheduled for Wednesday in the Kootenays, with a resounding show of union support set for the end of the week in Vancouver.

Still hoping to rein in the teachers with the long arm of the law, the government appointed Leonard Doust as a special prosecutor to consider laying criminal contempt-of-court charges against BCTF leaders. His appointment followed a remarkable decision by Crown prosecutors not to pursue the matter because of a possible conflict of interest arising from their own labour tussle with the government. Public support remained solid. A poll released during the strike’s second week found only 37 percent opposed to the teachers’ illegal walkout. On Wednesday, as planned, thousands of public- and private-sector workers in the Kootenays walked out in support of the teachers. The much larger walkout planned for Friday in Vancouver was ready to go.

But the prospect of growing labour tumult, now involving the private sector, had persuaded the Liberals to drop their long-held demand that teachers lift their picket lines before agreeing to talk. Troubleshooter Vince Ready was brought in to facilitate an end to the strike, while Gordon Campbell sent over trusted adviser Ken Dobell to represent the government. After a round of his patented marathon bargaining, Ready opted to issue his own recommendations, which was enough to put the Vancouver sympathy strike on hold.

Although he kept the government’s basic wage freeze, Ready threw in a lot of other money for the teachers and their issues: a major improvement in pay for teachers on call, $40 million to compress salary grids in the province, a one-time payment of $40 million to pad the teachers’ long-term disability fund and $20 million to help address class size and assist students with special needs. These were significant increases over the stringent contract imposed by Bill 12, but the government grasped Ready’s recommendations with relief, eager to extract themselves from the pit they had dug for themselves. The BCTF took its time. Some thought Ready’s proposals were not enough. In the end, a majority of the negotiating committee recommended that members accept the deal. They did, by 77 percent.

On Monday, October 24, the province’s teachers returned to their classroom duties with heads high. They had fought a two-week illegal strike against an intractable government and claimed a measure of victory. Although the wage freeze remained and former limits on class size and composition were not restored, few could deny the gains teachers achieved by fighting back against Bill 12. Almost lost in the end-of-strike bustle was the whopping fine ultimately handed down by Justice Brown for the BCTF’s defiance of the court: half a million dollars, one of the largest fines levied ever against a union in Canada.

Jinny Sims’s unyielding demeanour had played a big part keeping morale high during the difficult strike. Looking back, she said she was sustained through the trying times by starting every morning on the picket line. “There, I would talk to the teachers. That gave me strength, so I never felt like giving up. Jinny Sims didn’t lead that strike. The members led that strike.” Sims also credited the labour movement and the BC Federation of Labour for their mobilization. “When you’re right in the middle of something like this, that kind of support is overwhelming.” In addition to job action by private-sector workers and thousands of CUPE school workers who respected teacher picket lines, CUPE BC president Barry O’Neill called other members off the job for one-day walkouts on Vancouver Island, the Kootenays and northern BC, where “CUPE Day” saw fifteen thousand members in fifteen communities rallying to the teachers’ cause. “We thought we were going to be out there alone,” said appreciative Terrace teacher Veralynn Munson. “We cannot say enough about the role of Barry O’Neill. They were at our side right from the beginning. I will remember it for my lifetime.”

The strike was followed by a five-year respite from hostilities, thanks to a rare even-handed approach by the government and the teachers’ willingness to accept an unprecedented lengthy agreement. The deal, part of finance minister Carole Taylor’s pre-Olympics largesse, provided a 16 percent wage increase over its five years. Each teacher also received a $4,000 bonus. It proved a welcome calm before the storm resumed.

The 2006 softening of the government’s hard-hearted approach to public employees, including teachers, may have been prompted by the NDP’s strong electoral comeback the previous year. Under new leader Carole James, the NDP had rebounded from its devastating defeat in 2001, gaining thirty-one seats and boosting its share of the popular vote by 20 percent. The Liberals’ popularity dropped nearly 12 percent. Much of that could be attributed to the BC union movement.

During the Liberals’ first term, with the NDP reduced to two fighting but lonely MLAs in a sea of seventy-seven Liberals, labour had functioned as an unofficial opposition, taking on the government over its anti-union policies and rallying public support. Unions were heavily involved in the 2004 municipal elections, supporting candidates who swept Vancouver and won nearly two hundred council seats across the province. And the BC Federation of Labour’s million-dollar fund for grassroots organizing among rank-and-file union members brought many back to the NDP fold.

Although the Liberals still won a thirteen-seat majority, few doubted that the fight against their harsh policies had caused a rethink, at least for the moment. The government also had a healthy surplus thanks to a comeback in natural gas and resource revenues, after record deficits caused by its startling 25 percent cut in income tax. The result was finance minister Carole Taylor’s billion-dollar bonus for nearly three hundred thousand public-sector workers. Noting that they had paid an economic price for the government’s restraint program, Taylor said they should be rewarded now that budgetary times were better. Union members who reached new four-year contracts before their existing agreements expired, strategically taking them beyond the next election and the 2010 Olympics, would receive signing bonuses of around $4,000 each. This was more than chump change. Not a single public-sector union failed to meet Carole Taylor’s clever deadline in order to cash in.

Unions also took advantage of Taylor’s emphasis that there would be no “one size fits all” template to address built-up grievances. For the battered HEU, that meant annual wage increases of 2.6 percent, adjustments for those in high-demand positions, renewed limits on contracting out and the Taylor bonus, especially appreciated by those at the low end of the wage scale.

Then came the sweetest payback of all. Almost unnoticed, the health unions’ constitutional challenge to Bill 29 had made it to the Supreme Court of Canada. After the case was argued in February 2006, led by constitutional lawyer Joseph Arvay, it would be another sixteen months before the justices of the Supreme Court of Canada handed down their ruling. When they did, on June 8, 2007, the decision was a blockbuster. Nearly five and a half years after Bill 29 was rammed through the legislature, the Supreme Court struck down critical sections of the bill as a violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. By a solid 6–1 majority, the court agreed with the union that unilaterally removing protection against contracting out, eroding employee bumping rights and slicing layoff notices from six months to sixty days contravened the charter’s guarantee of freedom of association.

For the first time, Canada’s highest court enshrined collective bargaining as a constitutional right. The justices shredded Bill 29 because the Campbell government had made no attempt to negotiate with the unions before taking a legislative meat cleaver to their contracts. In clear, unmistakable language, the court declared, “Recognizing that workers have the right to bargain collectively as part of their freedom to associate reaffirms the values of dignity, personal autonomy, equality and democracy that are inherent in the Charter.”

This right was now constitutionally protected under the charter. In one of those great ironies occasionally delivered up by history, the unprecedented catastrophe for the HEU had culminated in the most significant legal victory for unions in Canadian history. No longer would governments be able to impose contract conditions willy-nilly on a union without first trying to reach a settlement through meaningful bargaining. The BC Federation of Labour has since proclaimed June 8 as Collective Bargaining Rights Day in British Columbia.

Union president Jinny Sims, speaking to the teachers’ mass rally at the legislature, never wavered in her strong leadership of the BCTF throughout its risky, high-stakes illegal strike in 2005.

Joshua Berson photo.

The Hospital Employees’ Union could scarcely believe the result. After so many dark days, so many members privatized onto unemployment lines in favour of workers paid barely half the union rate, it was truly a victory to savour. “I can tell you, my phone, my email, people coming into the building … they are jubilant,” secretary-business manager Judy Darcy told reporters. “They jump for joy, they cry, they shriek… They have been through absolute hell.” The Supreme Court provided the Liberals a year to set things right with the HEU and other involved unions.

Seven years to the day that Bill 29 received royal assent, the unions announced they had reached a settlement with the government. The package included $70 million for the thousands of workers who had lost their jobs through Bill 29, $5 million for retraining workers laid off within the current contracting-out cap, restored bumping rights, at least sixty days’ notice of further planned privatizations, and the right of health-care unions to propose alternatives in order to keep services in-house. This was the kind of fairness that had been missing in action in 2002, and HEU members voted overwhelmingly to accept it. There were more critical decisions to come. But after all those decades of courts giving workers the short end of the stick, who would have expected the Supreme Court of Canada to emerge as trade unionism’s great defender?