The Magic Quirt

GIT up, there, you, Mac! Gieup, Bessie! Carnsarn ye for a pair of busted-down, walleyed, spavined ignorantipedes! Gettin’ so a man can’t even git ten winks on his own chuck wagon without you buzzard baits clownin’ up!”

Old Laramie curled twenty feet of whip into a powerful pop about their ears and the pair of swaybacks began to pull once more. The chuck wagon clattered and rolled over the last small hump and started down the curving, treacherous trail which led into and through Daly Canyon.

A horse is often wiser than a preoccupied man and Bessie or Mac might have had something to say if they could talk. For two wagons wouldn’t pass on this narrow, precipitous trail. They let the whip pop away their caution and downward they shuffled.

Old Laramie had not liked being disturbed. It was just about dusk and shortly he would be elbow deep in the onerous duties of the cook of the Lazy G.

When the horses had shied and stopped he had been halfway through a little book titled: The Secret of Power, A Twenty-Five Lesson Course in the Occult Sciences, Giving the Student Positive Control of His fellow men.

That was for Old Laramie. By gad, if he didn’t get some control over somethin’ pretty soon he was going to turn Digger Injun complete with breechclout and let ’em all go to the devil. For ever since Lee Jacoby had come as foreman to the Lazy G the life of Old Laramie had been worth less than a secondhand chaw of Old Mule.

“Hey, you cookie!” Lee Jacoby would howl. “Do you call this chuck, or did you make it to shoe horses with?” Or, “My Gawd, cookie, I didn’t know you was a expert on mixin’ poisons. Boys, we ain’t got a cook, we got a apothecary! Throw it out and get me some ham and eggs.”

It was the quality of the wit which injured. For as an old-time chef of the cow camps, Laramie was not unused to joshing. But ye gods, it ought at least to be funny. And it never, never, never ought to be followed up with dumping perfectly edible chuck on the ground.

The punchers of the Lazy G followed the leader. They weren’t the old crowd. Ever since the Kid’s pa got killed in Laredo, old hands had been drifting. First came Lee Jacoby with his cock-o’-the-walk brutality and then followed rannies who better suited the foreman’s taste. They never consulted the Kid.

Young Tom Gregory had lost his mother when he was born and his old man when he was thirteen. And now at fourteen he was owner in title only, the Crawford County Bank—meaning old man Williamson—actually running the spread. It was all legal enough but things were happening. One of these days the Kid would have to drift, penniless. And Old Laramie was trying hard to stand by.

“By cracky,” sighed Old Laramie, thumb in the book and eyes vacant, “if I could do just one-sixteenth the things this Hindu feller says I can, I could run that Lee Jacoby plumb off’n the range. And Williamson to boot.” He looked back into the book, read a moment and then growled with determination, “And the Bolger twins likewise!”

Rapt in this glorious dream, he didn’t even begin to hear what was happening ahead. He drew an imaginary gun from an imaginary holster and said to the imaginary Gus Bolger, the same that had shot the Kid’s pa, “Ye’re powerless! With the magic wave of my left paw I creates you a statue! With a quick thumbin’ of my right, I creates you a corpse!”

BANG! BLOWIE!

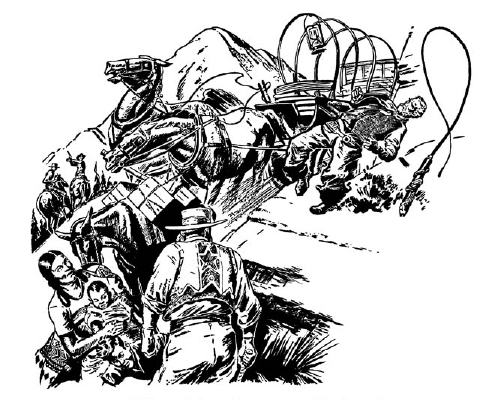

But it wasn’t Old Laramie’s imaginary gun. It was a real, honest-to-gosh shootin’ iron. And Bessie and Mac recognized it as such, reared against the remorseless weight of the unbraked wagon, got shoved ahead, reared again and then, bronc fashion, scared to death, lit out like the Cannonball Stage straight down the curving road.

Whoever it was that had shot was not in sight. The road’s curve hid him. But the speed with which Old Laramie was traveling would very shortly remedy that.

His old slouch hat whipped back in the hurricane and the chin thong nearly strangled him. He tried to grind home the brake shoe but he missed and had to use both hands and both feet to hold on. The reins were loosely tied to the brake and to reach them was impossible. He couldn’t reach his rabbit’s foot and his Little Jim Dandy Guaranteed Lucky Ring was carelessly left in camp!

Old Laramie once upon a time had been as tough as the next one, but three bullet holes, a sense of defeat and old age had ended that. He screamed like a wounded mountain lion and the scenery blurred by.

The chuck wagon finished the curve on two wheels, swapped to the other two, came back and tried to lean over the hundred-foot drop into the dry arroyo.

Straight ahead were six pack animals, clinging to the cliff beside the road as only burros can do. Directly in the track of the plunging wagon were two mounted men, holding guns on somebody or something out of Old Laramie’s view.

But the horsemen weren’t there long. They gave a white-eyed look at the cometing wagon and dug spur. Their outraged mounts reared and fought, to break away down the road in an uncontrolled run. The riders were out of sight and still going an instant later when Mac, tangling with a sideswiped burro, upset the chuck wagon entire, flat and loud in the middle of the road.

Old Laramie floated to an easy landing in sand and sagebrush. The sound of breaking crockery gradually ceased to echo in the surrounding arroyos. The dust dropped slowly down in the dusk.

Old Laramie floated to an easy landing in sand and sagebrush. The sound of breaking crockery gradually ceased to echo in the surrounding arroyos.

Old Laramie spat, sat up, felt of his bones and then swore luridly and long. That seemed to relieve him somewhat and he looked at his horses. They were bruised but had struggled to their feet with no bones broken. The chuck wagon, however, had spilled everything from frying pans to cockroaches.

“¡Ah, gracias, gracias!” wailed somebody. “¡Gracias, amigo! ¡Gracias infinitas para todos mandados!”

Old Laramie understood very little Spanish but he knew he was being thanked and he turned to find a small, fat Indian from over the line waddling up, bowing and advancing.

Three small children now rose wide-eyed from the sage and a woman, as fat as her man, came off a rock above the trail carrying a fourth child.

It was a very strange thing, thought Old Laramie. Sure these Mexican Indians didn’t seem to be good bait for the owl-hoots.

The flood of Spanish went on with much flinging of the arms, and when it seemed that he was about to get kissed by the woman, Laramie got gruff.

“Hell, wasn’t nothin’! Gimme a hand with this yere wagon.”

They gave him a hand. The three kids picked up groceries and pans while the man and his wife aided to rig a block and tackle to right the wagon.

It was quite dark when the task was done and Laramie, less breakage, was ready to proceed on his way. He was getting mighty anxious when he thought of how Lee Jacoby would take this. For he should have been at Camp Seven something before supper time.

The little Indian was jabbering with more thanks.

“Quit it,” said Laramie. “I would’ve done it for anybody. But just now I got to go.”

“¡Señor, su pago!”

“Pago yourself,” said Old Laramie genially. “But I got to go. I’m goin’ to be roasted, clothes, hoofs and hide, as it is!”

The Indian was pulling forth a fat sack. From it he poured a small torrent of silver and gold coins. Laramie’s eyes popped. So that was the bait! But he found that he was about to be paid. This unsettled him.

“Dang it, you ornery little cactus-eater. I didn’t do you no favor on purpose. My horses run away and…”

The Indian tried to push the money at him but he finally succeeded in pushing it back. There was an immediate conference between the Mexican and his wife and finally the man went to the sad little burros and dug into a pack.

The thing which he now extended to Laramie glittered in the starlight. And the man made a valiant attempt at English.

“See! Thees theeng. Látigo. Make beeg man. Muy fuerte man, látigo he take. Beeg man make. Muy fuerte. Me not Indian. Me Aztec. You savvy? You keep. You beeg, beeg man. Mucho lucky. Mucho!”

Puzzled, Laramie took the object and found it to be a silver-mounted quirt. He was too anxious to get to Camp Seven to delay and so, saluting with the quirt, hastily got started before the thanks began again.

Mac and Bessie picked their way amongst the rocks of the canyon and soon came out on the flat where, in the distance, a fire marked the whereabouts of Camp Seven.

Laramie drew up beside the blaze and found Lee Jacoby standing there, eyeing him with his usual evil glare and perhaps something more.

Without palaver, Laramie got down, threw the back of the wagon open and hurriedly began to throw cold beans and sowbelly in the direction of the blaze. Working so fast he was nearly a blur, he had supper ready for tin plates in less than fifteen minutes.

With an occasional grin and gibe the punchers jostled each other past and carrying their handouts and coffee mugs to nearby stones, soon ended the meal.

All this time Lee Jacoby had said nothing. The silence was worse than a tongue-lashing and when Laramie had handed the big black-eyed devil his chuck, the old cook shuddered. But still Lee Jacoby said nothing.

Later, when he was cleaning up, Laramie ruminated upon it uncomfortably and the Kid, coming up, had to speak twice before Laramie heard him.

“Oh, hello, Kid.” He stopped and looked closely at the youngster. It was plain, even by the fitful firelight, that the Kid had been crying. “What’s up, Kid?”

“Nothin’, Laramie.”

“Workin’ too hard, mebbe?”

“Naw. Hell, it’d be a relief to work. I just rode out to see how things was doin’ here.”

“Somebody dress you down mebbe?”

“Naw. What do I care for these big stiffs?”

“Well, mebbe the bank, huh?”

The Kid was silent and quickly changed the subject. “That grub shore was welcome, Laramie. Ever since Sing Lee quit at the main ranch, I just about starve to death.”

“Sing Lee? Come on, now, Kid. Why would he quit? By jumpin’ sassafras, somebody…”

“Naw, Laramie. It just had to be that way, that’s all. Williamson said a private cook for the owner might have been all right when my pa was alive but it was silly payin’ a Chink just to feed one boy. It’s the beginnin’ of the end, Laramie. With stock disappearin’…”

“Kid, I been out in the camps for three solid weeks and today I was out of grub and had to go in to Crawford and that’s as near to news as I been in a month. Why in the name of Beelzebub didn’t you tell Williamson to go to hell? Why, if I’d been there—”

But he broke it off, suddenly ashamed. If he’d been there he would have done nothing. It was hell to have your nerve gone. There had been a time when he hadn’t been Old Laramie. Young Laramie had been a gentleman to walk soft around. But that was before Bill Thompson. If he’d been there, he wouldn’t have done a thing.

He got back to his dishes, the water raw and stinging on the scar of his gun hand.

The Kid started to dry on a flour sack. “Them damned Bolger twins rode through about an hour back,” he said conversationally. “Seemed like they were in a hurry. Horses all lathered…”

“By the Eeternal!” cried Laramie, slapping his thigh. “By the Eeternal! Them’s who it was!”

And he promptly told the Kid in confidence what had happened back in Daly Canyon. Nearly finished, he reached into the wagon and pulled out the quirt.

“Say!” said the Kid. “That’s foofaraw!” And he turned it around in his hands. “What’d he say?”

“He said…hell, I never could get the hang of that spiggoty stuff. He said he was a Aztec and that this here thing would make me a big man.”

“Aztec! Say, Laramie, there’s an Aztec priest lives over by Blue Butte. Regular medicine man he is. Cave full of bats and stone idols. I been over there six, seven times but I never had nerve to go right up to the place. But one day nobody was home and I rid close by and peeked in. And say, it’d make your blood run cold. Stone idols with big green eyes. I bet he makes human sacrifices and everything.”

Laramie looked wonderingly at the Kid and then at the quirt. For the first time he saw the design. The handle consisted of a coiled serpent whose head was the top and two great green eyes stared back at him. Suddenly he felt bewitched and thrust the gift from him.

“You’re lucky he didn’t put no spell on you,” said the Kid, sagely. “I remember when Sing Lee almost jumped out the window when that old Aztec come up to the door. Sing Lee said he was a devil with an evil eye. If I was you, I’d put that away mighty careful. There’s no telling what it might be.”

Half-hypnotized by the green-eyed serpent, Old Laramie shoved it out of sight, he knew not quite where in the darkness. He had not the benefit, any more than the unlettered Kid, of a higher education which sternly forbade superstition. And besides, that snake was enough to give anybody the creeps.

The fire burned low and the punchers took to their sougans. And Old Laramie soon slept between the wagon wheels, wondering about what would happen to the Kid, wondering about why Lee Jacoby hadn’t jumped him, and then tangling all in a series of dreams which culminated in a nightmare so horrible that it brought him stifled from out of his blankets, pawing for his foes, every hair erect on his head.

The fire was out and the night was still. A coyote answered another coyote and then a wolf, with a low, quavering moan, silenced all the lesser beasts. A gibbous moon cast a sickly light across the plains. It was still, it was lonely.

Old Laramie’s heart quieted down and he sank back. But the bed was uncommonly uncomfortable and he twisted about for minutes before he finally investigated.

It was the quirt. He had shoved it into his blankets in error and on retiring had mistaken it for a rock. He whipped it out and it glittered in the moonlight, the two green eyes glaring at him.

“Make beeg man!” the little Injun had said.

Old Laramie scowled. But it was a funny thing about the quirt. It didn’t seem to be so unfriendly now. As he looked at it a quietness stole over him.

Supposing, he sighed as he lay back and covered his head, supposing that was really true. Supposing that just by owning this quirt a man got to be big and powerful. That was a comfortable thought. Suddenly he sat upright and worked his blanket toward the tailboard. He reached up with a knowing hand and brought down one of his books.

He thumbed the pages in the unsteady light of a match.

…But amongst all other magical religions, that of the Aztecs was the most powerful according to record. Those tribes which lived in Arizona and New Mexico at the time of the Spaniards’ coming were found to be in possession of much black magic, accounts of which have come fragmentarily to us from the early explorers.

It is said that some of these Aztec priests could produce howling storms at will and it was in one such that five men of the party of Juan Pérez perished. They had also the power of amulets and charms which, in their use, would protect the wearer against evil and create him a demon to his enemies.

It is stated in the Pérez Journal that by the use of such a charm one priest was able to withstand the shock of five Spanish troopers riding him down at full charge with lances. Unaccountably two of the troopers fell dead during the attack. The feathered serpent played a large part in the rituals of Aztec magic….

Unsteadily Old Laramie grabbed the quirt. The flaring match showed him something he had previously overlooked. The serpent on the handle had feathers! Feathers which gleamed palely by the light of the gibbous moon.

Next morning, Old Laramie ladled out the hot cakes to the men with an air of grand disdain. It was early, still dark, and the punchers were either too sleepy or too hungry to notice. For once no one made fast comments on the quality of the food and when they came back for thirds Old Laramie banged down a lid and began to clear away. There was no argument.

The sun came up shortly after the last cayuse had been manhandled into servility for the day’s work. Old Laramie stood around the deserted camp flicking his scuffed boot with the quirt and admiring the scenery.

How clean and clear it all looked! Funny, but the sky hadn’t been as pretty as this to him for twenty years. Not since he was a kid riding range in the Panhandle. The crystal air was better than a jolt of bar whiskey and the sage smelled like perfume.

He sang contentedly as he strolled and so engrossed was he in the atmosphere that he didn’t hear Lee Jacoby come up.

“Cookie!”

Out of habit Laramie turned in fright. But his new courage was too strong to be put down.

“Well?” he said stiffly.

“Get out to the holding corral and give the boys a hand with the wire. It’s been cut in fifty places and we need help. Now get!”

Laramie looked coldly at the foreman. Flicking his scuffed boot with the quirt, he said, “Since when, Mr. Foreman Jacoby, does a cook mend wire?”

“Since now!”

“Well, Mr. Foreman Jacoby,” said the old man with great dignity, “there’s your chuck wagon and you know where you can put it. Me, I’m cuttin’ me out a hoss and driftin’ to town for amusement. I’ll take fifty-seven dollars and twenty-nine cents wages here and now.”

Jacoby blinked at the stern face. Suddenly he yanked a pad out of his levis and wrote a note with a pencil stub. This he threw at the cook. Without further conversation, Jacoby wheeled his bay and rode out of the camp.

Old Laramie grinned insolently. He gave the quirt a masterful spin and flicked the fallen note so that it rose to his hand.

Mr. Williamson:

Pay bearer $59 in wages. Also send me new cook today.

Jacoby at Camp Seven.

Laramie cut himself out a mean-eyed sorrel, pulled his saddle gear out of the chuck wagon and, with his worldly possessions on the cantle behind him, rode in great dignity due north across the flat to re-enter Daly Canyon.

He had gone about three miles and had just finished contemplating his scene of triumph in great magnification when hoofbeats rolled up the road behind him.

The Kid drew up beside him on a blowing American saddler.

“Gee whiz, Laramie. Gee whiz. You’re not walking out. Gee whiz, you’re the last man left of the old outfit! Come on, Laramie. Please don’t do that. You don’t know…”

“Sonny,” said Laramie, “if you want to take a ride, come along into town and watch my triumph.”

Saying which, Old Laramie produced a Colt .44 from thin air and blew a straggling cactus clean out of the ground. He whuffed the smoke from the barrel and slid the weapon into its holster.

“Gee!” said the Kid. And then worriedly, “What’s up, Laramie?”

The old puncher grandly ignored the boy and they rode through the warming day toward Crawford. After a couple hours the false-fronts and ’dobe of the town shimmered into sight through the heat waves.

Laramie tied the mean-eyed sorrel up to the rail in front of the bank. “You wait here,” he said, and, bowlegs creaking, waddled into the front door of the bank.

It was dim and cool in the interior and it took a moment for Old Laramie’s ancient eyes to accustom themselves to the gloom. Finally he saw Williamson beyond the counter at a desk.

Without ceremony Old Laramie shoved through the gate and dug the note from his belt to toss it on the desk.

Williamson was looking at him oddly. The man was bald and fat and he hid a deal of craftiness under a large amount of false bluster. He seemed to have no bluster left, however.

Without taking his fascinated gaze off Laramie, he picked up the note. After a little he distracted himself enough to read the words. His hand shook a trifle and he got up hurriedly.

“Give this man his pay,” said Williamson to the cashier. And then to Old Laramie, “Are you leaving town?”

“Don’t reckon I will for a spell,” said Laramie with a very tough scowl.

This seemed to give Williamson a great deal of reason to think. He retreated to his desk and sat there staring at Laramie. The puncher yanked his money to him and stuffed it in his belt. With one last truculent glare at Williamson he went out into the glaring sunlight and untied his sorrel.

“What’s it all about?” blinked the Kid.

“Everything just goin’ fine,” said Laramie. He led his horse down the street to the Oasis Saloon and tied him up again.

The Kid tagged in after him, wondering if Laramie meant to go on a drunk. But Laramie passed straight on by the bar and came up before a faro layout.

The gambler was amusing himself in the deserted house by betting small sums against his own bank. He had had a good lunch and felt peaceful. He smiled woodenly at Laramie, very glad to have a customer who might, even this early in the day, attract others.

Laramie glanced at the picture of the tiger on the wall and then at the thirteen spades face up on the layout.

“Like to do some gamblin’?” said the dealer unnecessarily.

With a flip Laramie threw the gold piece on the bar. The dealer swept the double eagle into the till and advanced twenty dollars’ worth of chips. He shuffled the deck, cut it and thrust it into the dealing box.

“Soda,” showing in the deal box, was the ten of diamonds. Unreasonably, since there were only three more tens in that deck, Laramie tossed five dollars on the spade ten on the layout.

The dealer grinned inwardly, for here he was sure he had a fool whose money would soon be parted. He laid soda aside, his long white fingers sliding it smoothly out of the box. The six of hearts came to view. This, being the losing card, he slid out and placed beside the box. And as it slid, the ten of clubs came startlingly into view. The dealer permitted no sign of surprise to escape him. He paid the bet, kept the case on a board beside him, watched for Laramie to make his next bet. He permitted, again, no sign of amazement. For Laramie let it all ride on the ten, to win.

Neatly, the dealer discarded the last winning card and disclosed the three of diamonds as the next loser. This he laid beside the box, starting a precise pile. He blinked ever so slightly. For there lay the ten of spades. There was just a hint of jerk in his hand as he tumbled out the chips.

He kept the case, saw that Laramie had left the whole pile on the layout ten and, with some slight impatience, discarded.

The next losing card was the three of spades and with a yank which he intended to be triumphant, the dealer pulled it and started to lay it in the neat pile. His hand halted midair. For the ten of hearts had been disclosed to full view.

Angrily the dealer thumped the chips down on Laramie’s bet and by now the pile was spilling both ways. Laramie raked it all in, unsmiling, confident, and laid four blues before him.

“Now I think I will try aces,” said Laramie.

The dealer permitted himself a private grin. He’d get that stack back. No fear of that. And so he put the discard aside, laid out the nine of clubs as the loser and then scowled blackly at the ace of diamonds which beamed at him from the deal box.

The chips nearly cracked as he paid the debt.

“Lettin’ it ride?” snarled the dealer.

“Nope,” said Laramie, matter-of-fact. “That next winner is goin’ to be a two spot.” And he bet eight blues to prove it. “And if you twist the deck around any, yore lungs shore could stand some ventilation.”

The dealer discarded, disclosing the jack of spades as the loser and then slipped this out to find the two of spades lying in full view.

The Kid understood very little of faro and cared less. He was uneasy at this change in his friend and, besides this, the sour smell of the saloon gagged him slightly. He wandered out into the street and watched two dogs fighting halfheartedly in the heavy dust of the road.

This was so slow that he glanced around for greater amusement and was rooted by the sight of Gus Bolger stepping out on the sidewalk before the bank, with Williamson at his elbow.

He knew it was Gus, for he was the smaller of the fraternal twins. The man’s face was narrow, his visage dark, his eyes light gray and cold. Everything about him seemed stealthy and shadowed. Gus Bolger turned from the banker and waved covertly to someone across the street. Then, keeping to the wall, Bolger came toward the Oasis, hand resting on his gun butt.

The Kid trusted he had not been seen. He backed hastily into the Oasis and sprinted to the faro layout.

“Laramie! Gus Bolger is comin’ in here!”

“Don’t pester me, sonny,” said Old Laramie with impatience. For he had just lost his first bet and though it had been small it bothered him. He was about to place his next and copper it to lose when the import of the Kid’s message came into his brain.

He heard a light footfall in the door and whirled.

Gus Bolger stood, lightly balanced, leaning slightly forward, gun hand tense and still, at his side. “You there at the table. Come outside. I want to talk with you.”

Laramie felt his heart start to climb and then the quirt brushed his leg. He steadied. “If yore so anxious to converse, I reckon this is as good a spot as any.” He was aware of the dealer ducking into cover and the lone bartender vanishing behind the glasses on the bar.

“Come along here,” snapped Bolger. “You wouldn’t want to make trouble.”

“I ain’t makin’ no trouble. But mebbe I’ll unmake some. Say your say, Bolger, or draw—if yuh ain’t too yeller.”

The Kid was shaking as he moved to one side. He had no gun and his only friend in the world was about to leave it. For Bolger was known for these things. And the Kid’s pa, though it was said in Laredo that the break was far from even, had been killed by this very man.

Bolger’s hand blurred, his left stabbed down to fan. But he never connected with his hammer.

Three shots, tight together and loud as doom, shook Gus Bolger back, back, back.

Bolger, dead even as he fell, lurched into the window and fell sideways amid a shower of glass upon the boardwalk.

The last piece shook free from the arch which said “Oasis” and fell with one last musical tinkle.

With a quick sprint Old Laramie reached the body, gun ready just in case. But his last shot had been high and there wasn’t any reason to suspect, from the look of the face, that Bolger would terrorize anyone again.

The Kid screamed, “Look out!”

Laramie dived sideways and a slug tore splinters from the walk where an instant before he had stood. Laramie wheeled toward the report, still falling sideways.

Across the street, Winchester raised and sighted, was Ray Bolger, striving insanely to get Laramie in his sights again.

But his horse was restive and shooting from the saddle was not good.

Ray Bolger dived out of leather and behind one of the fire barrels which lay at intervals in the street.

Laramie scrambled under a hitch rail and took cover behind the Oasis watering trough.

A slug struck a nail and glanced away with a shrill metallic yowl.

With an unsteady hand Laramie replaced the three empties in his .44. He saw the Kid hovering in the doorway behind him.

“Git out o’ that!” he yelled.

The Kid dived back into the shadows and another slug broke the remaining window of the Oasis. But the shot had cost Ray Bolger his cover for an instant and Laramie took a snap shot at the exposed gun barrel and hand.

The shot was too tough and the next moment another bullet yowled away from the trough. A third drove through the corner and a stream of water jetted out to raise dust as it hit.

Laramie gripped the quirt. He looked behind him and saw a three-foot opening under the high boardwalk. Snake-fashion, keeping cover with the water trough, he went under the walk and, in its shadow, worked his way ten feet to the left.

Anxiously Bolger was seeking his enemy, exposing part of his face, then his shoulder.

Drawing very careful aim, the old cowpuncher sighted and let the hammer fall. The bullet glanced from the side of the water barrel and tore flying splinters away. Blinded and crazed with the pain of his lacerated eyes, Bolger sprang up and took the second shot, instantly following, squarely in the chest.

Laramie cautiously sidled across the street, eyes leery for another attack. He rolled Ray Bolger over with his foot. The man was breathing hoarsely.

There was a flurry of action in front of the bank a moment later. Williamson caught up the Kid’s American saddler from the hitch rack, mounted and started to spur away.

Laramie blinked, saw the wild backward glance Williamson gave him which suddenly made sense.

He levered a new cartridge into Bolger’s Winchester and very carefully laid his sights. The target was a hundred yards off but traveling straight away.

Laramie squeezed the trigger. He thought he saw the banker lurch but he did not fall and the saddler went streaking out of range.

The dealer and other citizens came out to cluster around the dead man and the wounded gunman. A doctor came shortly, still in his shirt sleeves as he had napped after lunch. He shook his head over Ray Bolger but had the man taken into the Oasis and laid on a pool table.

The Kid was standing popeyed before Laramie. Several citizens stood back at respectful distances and stared. Laramie took a long breath, hit his boot with the quirt and, with something like a swashbuckling air, went down to the sheriff’s office to give himself up.

This gesture was not climaxed. For the sheriff was not there and a deputy, following discreetly, told Laramie in a courteous voice that he didn’t have any authority, not having a warrant.

“The sheriff, he went out to check on some rustling,” explained the deputy. “And he won’t be back for a couple hours or so. Have a seat, sir.”

Laramie sat down in the sheriff’s chair, put his spurs amongst the scattered reward posters and built himself a cigarette. He was grandly unconscious of the citizens who, too late for the shooting, tried to look indifferent as they strolled by and stared in. Soon a knot of small boys had to be dispersed by the deputy, who came back, heartened.

“Sheriff’s comin’ up the road now. Got somebody with him, looks like. If you’ll wait just a minute, he’ll be right here.”

The sheriff dismounted and, thrusting people to one side and the other, gained his office. He had already been told by only slightly coherent witnesses in the last ten feet that he had a big gunman in there waiting to give himself up.

“C’mon in, Lee,” he called.

Lee Jacoby looked nervous. He glanced at the people, trying to make out what was going on and then, with a cinch on his nerve, started to walk in.

“Them Bolgers,” said a loafer from the livery stable, “was just about the toughest customers we ever had in these parts. I reckon…”

Lee Jacoby stopped. He hesitated and began to back, hand on his gun.

“C’mon, Lee!” insisted the sheriff. “Why…what the hell…?”

Laramie had gotten out of the chair at the first mention of Lee. He cat-footed to the door and there in the glaring daylight saw the foreman backing.

“Stop him!” cried Laramie, more lights dawning. “Stop him quick!”

Sheriff Quail never moved quicker than the spectators. He stepped to one side in the cleared lane, not knowing which man might be what. The deputy got himself a desk as a bullet backstop.

“Drop yore gun,” yelled Laramie, “or I’ll blow you in half!”

Lee Jacoby foolishly grunted in relief. He had been expecting at least a US deputy marshal. But Laramie…

“Stand where you be, Sheriff!” said Jacoby. “First man makes a move to stop me is a dead ’un!”

He had reached his horse and was about to mount. “Come down or I shoot!” yelled Laramie.

The old man never saw Lee Jacoby draw. There was flame and a smashing blow on Laramie’s hip and another which spun him half around. He fell across the doorway.

“Next man that gets ideas gets the same!” shouted Jacoby and completed the mount.

He started to swing away, smoking gun covering them all, when three explosions almost together tore at people’s nerves. The sheriff ducked back and when he looked again Jacoby’s horse was running crazily at the boardwalk across the street and one Lee Jacoby was slowly falling into himself in the dust. The foreman’s fallen gun was turning like a small pinwheel in the dirt.

After a while, when they had thrown a blanket over the body, they tried to pick Laramie off the walk. But he was not in a mood to be manhandled.

“Git off’n me! By gollies, it’s gittin’ so a man can’t even rest without havin’ a whole stampede making a trail of him.”

They helped him to his feet and looked for blood. And there was blood. The slug had struck his cartridge belt, exploding two bullets which in their turn had given him flesh wounds in the left armpit. But even so, the bruises made it hard for him to walk.

“Sheriff,” said the doctor, “Ray wants a word with you before he passes…. What’s this? Another one?”

“It’s Bunker Hill Day,” said the sheriff grimly. He started to the Oasis.

“No,” said the doctor, “he’s in the Emporium. Said he didn’t want to die in a saloon with his boots on. So he’s in amongst the dress goods, if it makes any difference.”

The Kid helped Old Laramie to follow and they found the dying gunman holding on hard to what life remained.

“All right, Bolger,” said the sheriff. “What is it?”

“I got something to say. The old ’un…the old ’un got Lee, didn’t he?”

“Dead center,” said the sheriff.

“I ain’t no Sunday-school boy, but I got my ideals,” said Bolger. “Got any fault…fault to find with that?” he added belligerently.

“None,” said the sheriff.

“Well…I tell you. I ain’t goin’ to Hell with murder on my soul. Gus is dead. Lee’s dead and the sawbones says I won’t be long. It was me who done in Tom Gregory, this kid’s pa, in Laredo. Gus stood him up for a showdown and pretended to draw…. I shot him from an alley.” He brooded for a moment and then, “He never even seen me.

“And it wasn’t even because I didn’t like him. He was always straight with us. So…so I got another score to pay off. It’s Williamson. Go down and get him because it was him paid me and Gus to kill Gregory.

“Get Williamson. And hang him for murder. ’Cause he’s killed Gus and Lee and Gregory, and all because he wanted money.”

After a little he added, “Money ain’t worth a damn compared to a man’s life, is it?” He saw then that they knew he was crying because he wanted to live and the day was bright. “Get the hell out of here!”

“Wait a minute, Ray,” said the sheriff. “You say Williamson did something. But what?”

Ray Bolger looked at him incredulously. “You mean…you mean you wasn’t told? I…”

“What’s what?” said the sheriff.

“Why, hell. Williamson was the one that hired us to kill Gregory. He put Lee in charge as foreman of the Lazy G and then he hired us to rustle stock off the Lazy G until he could force out young Gregory.

“We run the stock over the border. But a Mex’s took it and sent the pay back by an old Indian. Aztec he said he was but I don’t savvy too much Spanish. Gus did that. Used a bunch of kids and pack burros as a blind and came up here to tip us off for the next drive and to bring Williamson the pay they wouldn’t trust to us.

“I…I don’t savvy nothin’. But…anyway the old Indian wasn’t satisfied with his cut. And he was blackmailing Williamson. So Williamson refused and sent me and Gus out to kill the blabber. But a wagon come down on us while we was doin’ it and we dasn’t stay. We thought we hit him but they wasn’t no blood out there this morning and we couldn’t find the Indian.”

Bolger looked with agonized eyes at Laramie. “He…he didn’t even tell you?”

“I don’t speak no Spanish,” said Laramie.

“Oh, my Gad!” wept Bolger. “All for nothin’…all…for…” He began to cough and Laramie turned away.

“Well, Kid,” said Laramie, “you got your spread all set. Because what Williamson got paid will be adjoodicated to be your’n. And I guess I better go back to buckin’ that tiger.”

“Laramie,” said the Kid. “Laramie, would you take the job of foreman? At a hundred and fifty a month?”

Laramie looked at the Kid and smiled. “Shore. Glad to. But now—”

“Old Aztec, huh,” the proprietor of the Emporium was saying. “Who’d have dreamt it? Why, that fat old geezer and his lardy wife used to come in here every couple weeks and sell me a lot of trash cheap. Like these.”

Laramie turned, suddenly interested, and found that the storekeeper was holding up a very interesting item.

“Fancy, huh?” said the storekeeper. “All the big ranch owners across the border carry them. Mark of a big man. Two-fifty if you want one as a souvenir, Mr. Lara— But I see you’ve already got one.”

Laramie was stricken.

“What’s the matter?” pleaded the Kid, afraid.

The deputy came in to find the sheriff. “We got Williamson. He was plugged so bad he fell off about a mile east of here and a puncher brought him in. Let’s— Hey! What’s the matter with you, Mr. Laramie?”

But Laramie was past hearing. His eyes, resting on a rack of silver feathered-serpent quirts, fifty just like his own, began to glaze.

The amulet slipped from his fingers to the floor and Old Laramie, in a dead faint, sagged down on top of it, out cold.