Although it has been rightly criticized as the truest evidence of their collective inclination toward superficiality, Generation X’s obsession with popular culture, at least as seen in films made by members of their number, really is a manifestation of the great theme that runs through the cinema of Generation X. Knowing some of the economic and cultural factors that make these people feel disconnected from society, it follows that they might feel a collective desire for escape into a made-up society of their own—hence the use of pop-culture references as a coded form of language. Because Gen Xers, speaking in the most general terms, aren’t tethered to family and other institutions in the ways that their predecessors were, they create a comforting cocoon of artifice.

They also, interestingly, create other replacements for the warmth and security of family life, even as they exhibit deep ambivalence for the traditional concept of what an American household should look like. Specifically, Gen-X filmmakers have made a handful of disturbing observations about the dynamics of American families, with a particular concentration on what happens in the nation’s suburbs. The fixation on the ’burbs is telling, because a fair number of this generation’s filmmakers seem to have emerged from the affluent milieu of America’s middle class. Just as they sometimes display an insular affection for pop culture, they sometimes betray a sheltered perspective of what constitutes hardship.

The characters in Sam Mendes’s American Beauty, for instance, have it rough not because they’re poor, starving, or diseased, but because they’re not “fulfilled.” While it would be wrong to belittle the need for personal fulfillment, creative release, and professional satisfaction, the manner in which some Gen-X filmmakers treat the petty crises of the privileged as high drama is occasionally distasteful. (This trend reached an apex in The Game, David Fincher’s movie about a rich man who gets thrown into a life-or-death role-playing game because his brother thinks the protagonist needs to be shaken free of his constricting lifestyle.) Given the depth of need in countless parts of America and the rest of the world, films that portray comfortable, affluent lifestyles as oppressive are themselves oppressive, because of their tunnel-visioned perspectives.

Several interesting ideas emerge in these navel-gazing studies of suburbia, but some of the most resonant Gen-X films about family involve characters from further down the economic ladder. For instance, Jodie Foster—the exquisite screen actress who has been a familiar presence in American cinemas for so long that it seems odd to include her in a group so new to sociological discourse as Generation X, but who nonetheless fits in with that group chronologically—directed two thoughtful films about the issues facing blue-collar families. Her directorial debut, Little Man Tate, explored the peculiar quandaries facing the working-class mother of a genius child, and her follow-up, the mostly disappointing Home for the Holidays, looked at a less unusual, but more dysfunctional, nuclear family.

Both films make statements about the power of individualism and the need for family members to help loved ones unfurl their wings instead of clipping them, but perhaps the most important link between the movies is Foster’s strong assertion that family takes many forms: The unit formed by the genius and his mother in Little Man Tate is as enduring as that formed by the extended nuclear family in Home for the Holidays.

The ability to draw strength from unconventional family units is a key topic for Gen-X filmmakers. This is unsurprising, given the number of Gen Xers whose homes were cleaved by divorce, and given how many were raised by two working parents—meaning that as children, these Gen Xers often were left to fend for themselves or commiserate with peers while mom and dad were at the office. Sometimes, the shift from the traditional family unit is depicted as a tragedy (the protagonist of Fight Club suggests that men raised by women are by definition emasculated), and sometimes, the shift is reflected hopefully, as in stories about surrogate families. Such tales illustrate that love can create bonds as deep as those created by blood.

All Gen-X stories about family, however, need to be examined through the prism of the question that drives the generation: “Who am I, and where do I belong?” As so many societal factors made vast numbers of Gen Xers feel unwanted—they were abandoned, actually or metaphorically, by parents who left the home following a divorce; changes in schools and the workplace forced them to grow up fast, in effect truncating their childhoods; the corporatization of America made huge numbers of workers feel disposable; and so on—the ache that drives many Gen-X stories about family is poignant and sometimes heartbreaking.

The caveat to all this talk of profundity, of course, is that family is one of the basic themes of American popular culture, particularly television. Even if attention is focused solely on movies and TV shows of the 1970s, for instance, there is plenty of iconography related to that most crucial of issues, divorce. The Brady Bunch depicted a “blended” family created by the second marriages of a father and a mother; Alice, and the movie from which the sitcom was derived, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, showed a woman and her young son venturing out into the world following a failed marriage; the acclaimed feature Kramer vs. Kramer dramatized the effect that a divorce and its pursuant squabbles has on a young boy. This body of films and TV shows about new types of American families represented a substantial leap from the happy homes portrayed in such 1950s sitcoms as Father Knows Best and Leave It to Beaver. However, allowing that Generation X’s exploration of family isn’t an unprecedented foray into a new social frontier doesn’t diminish what the filmmakers belonging to this generation have to say. Quite to the contrary, this contextualization allows viewers to see how Gen-X movies about family deepen the discourse that came before.

Offering a tonal contrast to the cynicism that oozes through his films, Paul Thomas Anderson uses hopeful surrogate-family imagery to great effect in Hard Eight, Boogie Nights, and Magnolia. In Hard Eight, ne’er-do-well John (John C. Reilly) gets taken under the wing of veteran gambler Sydney (Philip Baker Hall); Sydney steers John through dangerous adventures in a casino and even facilitates his young charge’s romance with waitress Clementine (Gwyneth Paltrow). The older man’s altruism seems at odds with his hardened character, so it’s no great surprise at the end of the film to learn that Sydney actually is John’s father, protecting the younger man to atone for abandoning him years before. In this case, what seems to be a surrogate family is revealed to be an actual family, suggesting that fate sometimes offers opportunities for the rebuilding of severed bonds. This material is especially poignant for Gen Xers raised by “deadbeat dads,” fathers who mostly avoided their parental chores following divorces.

Severed bonds are a recurring theme in Magnolia, Anderson’s multi-character epic about people suffering from emotional, mental, and physical decay in contemporary Los Angeles. In one story line, a dying patriarch (Jason Robards) is brought together with the estranged son (Tom Cruise) who despises him; in another, a lonely policeman (John C. Reilly) stumbles into a haphazard romance with a drug abuser (Melora Waters); in a third, a pathetic former quiz-show champ (William H. Macy) timidly courts a studly, unreceptive bartender. These plot lines, and the others with which they intertwine, all dramatize the human need for connection, so the very fact that Anderson connects them as intricately as he does is a statement in itself: These people who crave connection are tethered to others, even if they don’t realize it.

Magnolia offers a complex vision of family, because it shows that traditional bonds can be infuriating—the patriarch’s trophy wife (Julianne Moore) numbs herself with sex and drugs to wash away the taste of marrying for money—while showing that nontraditional bonds can be empowering. The patriarch’s male nurse (Philip Seymour Hoffman) feels such empathy for his dying charge that he runs a gauntlet of red tape to arrange the father-son reunion. Magnolia is filled with little epiphanies and catastrophes, and the cycle of recrimination and redemption seems endless until a supernatural occurrence forces the characters to step out of their bubbles—in Gen-X terms, their insular perspectives—and see what’s right in front of them. The narrative problem with Anderson’s approach, and the aspect of the film that made it a love-hate proposition for audiences, is that the supernatural occurrence—a Biblical shower of frogs cascading down from the sky—is so freakish that it clashes with the intense credibility created by Anderson’s mesmerizing dialogue and forceful camerawork, and the luminous contributions of his actors. Still, Anderson’s point about the way people simultaneously crave and repel inclusion in the human community is touchingly made.

A similar statement is presented in Boogie Nights, the most accomplished of Anderson’s early films. A sprawling epic about two decades of pornographic filmmaking, Boogie Nights depicts how well-endowed Dirk Diggler (Mark Wahlberg) gets taken under the wing of skin-flick mogul Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds)—shades of the patriarchal altruism in Hard Eight. Dirk is accepted into the community that makes Jack’s films, which includes the director’s coke-addicted wife, Amber Waves (Julianne Moore), seemingly airheaded starlet Rollergirl (Heather Graham), ambitious porn actor Reed Rothchild (John C. Reilly), and others. The ironies of this family portrait are myriad. First, and most obvious, is that these people converge not to create real emotional intimacy, but to fabricate and exploit sexual intimacy: They are bonded not by love, but by lovemaking in its crudest incarnation. Another layer of irony is that people in this clique, excepting the technicians, are accepted not for their personalities but for their physicality: Dirk fits into the group because his large penis makes him a valuable commodity, Rollergirl fits in because her girl-next-door looks enable her to enact widespread sexual fantasies, and so on.

The horrific obstacles he lays in front of his Magnolia characters comprise a kind of narrative overkill, but Anderson lets a sensible, if hyperbolic, narrative guide his hand in Boogie Nights. Cultural shifts such as the transition in the porn industry from shooting on film to shooting on video force characters to adjust their trajectories, which allows Anderson to illustrate how this particular “family” reacts to hardship. The Dirk character is used to dramatize the journey undertaken by nearly every adolescent who breaks from his or her family to pursue an individual path, only to find that walking away from “home” leads to loneliness. Even worse, in Dirk’s case, leaving the nest leads to impotence. His virility stems from the connection he feels to his surrogate family.

The surrogate family also cushions the blow that Amber feels when she fails to win visitation rights to her actual child. The powerful sequence depicting Amber’s courtroom hearing and its aftermath adds another layer of irony to the film, for while Amber comfortably inhabits her role as a “mother” to the members of the filmmaking collective, she’s unable to mother her true offspring.

The final level of irony to Boogie Nights is seen in context of Anderson’s career, because he employs the same actors from film to film: His movies about surrogate families are made by a surrogate family. Yet while he has run further with this particular subject matter than any other of his peers, Anderson isn’t the only Gen Xer to illustrate the poignancy of people simulating familial love instead of inheriting it.

Morgan J. Freeman’s affecting Desert Blue depicts how the denizens of a tiny desert town in California bond with a father and daughter from Los Angeles who get stranded in the town. Echoing the lyrical tone of Scottish director Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero, Freeman’s movie uses oddball scenes and unexpected conversations to show that people have the ability to connect with strangers when their souls are in sync even if their lifestyles are not. The movie ultimately is as bright as Anderson’s are dark, so its mellow tone might be an acquired taste, but the message of inclusion and open-mindedness that Freeman puts across is universal.

The movie begins with cable-TV starlet Skye (Kate Hudson) reluctantly touring remote regions with her dad (John Heard), a professor who studies kitschy roadside attractions. They hit the town of Baxter to see the world’s largest ice-cream cone, but get stuck there when a chemical spill outside town forces a quarantine. As hesitantly as she accompanied her father to Baxter, Skye befriends young townies including Blue (Brendan Sexton III), a shy, haunted sort trying to realize the dreams of his late father; Ely (Christina Ricci), a doom-and-gloom type who gets her kicks by setting explosions; and all-terrain-vehicle nut Pete (Casey Affleck), whose prizes in local races make him the town hotshot.

Adventures in the skin trade: Gen-X movies such as Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights, with Mark Wahlberg (left) and Burt Reynolds as partners in pornography, depict characters from disparate backgrounds forming surrogate families (New Line Cinema).

These characters comprise a surrogate family demonized by Empire Cola, a conglomerate that built an ugly factory outside of Baxter but didn’t hire any locals to work there. Prior to the factory’s construction, Blue’s father tried to develop Baxter as a tourist destination by constructing an “ocean park” with water from an aqueduct that runs through town, but when water was appropriated for the Empire factory, construction of the park stopped. This turn of events led, in part, to the demise of Blue’s father, and one of the most resonant aspects of the film is the way that Blue’s friends nurture him through the pain, confusion, and angst that have consumed him since his tragedy. This familial imagery is a powerful representation of the manner in which Gen Xers often became each other’s stand-in relatives during times when parents were nowhere to be found and educators failed to provide adequate guidance.

Moreover, Desert Blue is a celebration of Generation X’s inclusive attitude toward different ethnicities, sexual preferences, and religions. Minorities, both racial and sexual, made tremendous progress toward gaining public acceptance during the years when Generation X matured, so the various Gen-X movies in which surrogate families are melting pots of different personality types reflect the tolerance that, while not reflected in every member of the generation, is one of Generation X’s most progressive attitudes. Desert Blue illustrates the ability that people have to see past how others present themselves—the townies, for instance, see the soulful person beneath Skye’s bitchy facade—so by the end of the film, even seemingly demented characters are sympathetic because we see the pain in their souls, their deep connection to other people, or both.

The surrogate-family imagery of Desert Blue and Anderson’s films recurs in various Gen-X movies, from Reality Bites (about a clique of twentysomethings joined by their postadolescent malaise) to Reservoir Dogs (in which hoods played by Harvey Keitel and Tim Roth develop something akin to the bond between a father and son) to X-Men (about freakish “mutants,” cast out by society, forming a team to serve the greater good) to Girl, Interrupted (in which the female patients in a psychiatric-care ward bond by sharing their dysfunctions).

One interesting twist on the prevalent surrogate-family imagery is found in You Can Count on Me, Kenneth Lonergan’s Oscar-nominated directorial debut. The film explores the relationship between Sammy Prescott (Laura Linney), a single mother living with her son in a small town, and Terry Prescott (Mark Ruffalo), her directionless brother. The two were orphaned during childhood when their parents died in an auto accident, so they have a special link: Notwithstanding Sammy’s son, they are each other’s only family. So when Terry drifts into his hometown for an extended visit with his sister, only to reveal that he’s caught in a cycle of self-destructive behavior, Lonergan makes some pointed statements about the ways in which a surrogate family can be deficient.

Sammy is the authority figure in this relationship because her life is on track, but her authority is diminished by her failures (including her marriage), and by the fact that she’s Terry’s sibling, not his parent. Terry resents her attempts at control and guidance, and dislikes that she judges him, so the sibling rivalry between the characters is exacerbated by Sammy’s endeavors to take on the surrogate-parent role. Yet for all his angst, Terry musters the strength at the end of the movie to declare what his sister’s love means to him: “It’s always really good to know that wherever I am, whatever stupid shit I’m doing, you’re back at home, rooting for me.” This confused young man has serious issues with the hand life dealt him, but in one of his clearest moments, he acknowledges that a having a surrogate family is better than having none at all.

One of the key factors behind Generation X’s collective makeup is the transformation of the traditional American family, and the ennui that consumed the millions of children who grew up feeling abandoned by their parents—and, by extension—by society at large. This ennui is given form in a memorable speech from Helen Childress’s script of Reality Bites, as spoken by quintessential slacker Troy (Ethan Hawke):

TROY: My parents got divorced when I was five years old, and I saw my father about three times a year after that. And when he found out that he had cancer, he decided to bring me here [to Texas], and he gives me this big pink sea shell, and he says to me “Son, the answers are all inside of this.” And I’m, like, “What?” And then I realize … the shell is empty. There’s no point to any of this. It’s all just a random lottery of meaningless tragedy, and a series of near-escapes. So I take pleasure in the details: a Quarter-Pounder with cheese … the sky … and I sit back and I smoke my Camel straights and I ride my own mount.

As Troy’s lament suggests, the dominant tone in Gen-X discussions of traditional families is cynicism, and the dominant family model featured in Gen-X movies is the dysfunctional nuclear clan infested with bitterness and resentment. The overrated, but nonetheless significant, American Beauty features perhaps the quintessential example of this skewed portrayal of family life in the United States.

Much of the attention earned by this Oscar-winning film was heaped on director Sam Mendes, a wunderkind Brit who secured his reputation with successful stage productions of Cabaret and The Blue Room. Both were sexed-up controversy magnets, and The Blue Room became a sensation in part because star Nicole Kidman briefly flashed her naked figure during each performance. Mendes therefore brought familiarity with handling stars and conjuring sensationalism to American Beauty, which was written by former sitcom scribe Alan Ball. Fitting his past employment, Ball brought superficiality and a penchant for one-liners. Together, the men crafted a breezily entertaining but insultingly obvious parable about the American middle class.

The story’s central character is Lester Burnham (Kevin Spacey), who loathes his job as a writer for Media Monthly magazine, and who is so devoid of hope that his long marriage to Carolyn (Annette Bening) will find new life that he masturbates in the shower every morning instead of trying to get intimate with his wife. Lester feels humiliated by everything about his existence, and wants badly to recover the hopefulness of his youth. He finds a possible mechanism for that recovery when he meets Angela Hayes (Mena Suvari), a pretty cheerleader friend of Lester’s daughter, Jane (Thora Birch). Emboldened by his flirtation with the precocious teenager, Lester quits his job, blackmails his employer, and even starts buying pot from Ricky Fitts (Wes Bentley), the haunted boy who lives next door. Meanwhile, Carolyn finds liberation of her own. Her career as a real-estate agent is stagnant, so she asks smooth-talking, handsome, successful homeseller Buddy Kane (Peter Gallagher) for advice. Her request eventually leads to a wild lovemaking session in a hotel room with her would-be mentor.

All of the story’s elements are clichés familiar from decades of soap operas, pulp novels, and disposable films: Lester pursues the tired mid-life fantasy of courting a cheerleader, then turns out to have a stronger conscience than expected; his would-be lover talks a tough line about sexual experience, but actually is a virgin; the pot dealer seems to be a burnout, but is in reality a soulful artist who finds transcendent beauty in the way a plastic bag gets caught in the wind. And Ricky’s father (Chris Cooper) is portrayed as a militaristic dictator with violent homophobia, so, naturally, he’s later revealed as a closeted homosexual.

Ball’s script deals almost exclusively in archetypes, then twists the archetypes predictably. The film’s limp message seems to be that true beauty is found in unexpected places, and that the sterile comforts of the American suburban lifestyle are truly ugly. The film’s final twist is that Lester, after throwing off his societal shackles and then proving his moral integrity by refusing to consummate his relationship with the Lolita cheerleader, gets killed by the homophobe whose same-sex advances he spurned. Lester isn’t punished for anything he did, but for something he didn’t do. The gimmick of the movie, which was used much more strikingly in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, is peeling back the plastic surface of suburbia to reveal festering dysfunction, but everything the film reveals is familiar and tame.

American Beauty is worth discussing in detail not because it makes a powerful statement about American life, but because it has been celebrated for doing so when in fact it does exactly the opposite. Ironically, the least profound of the Gen-X films that depict family issues has a reputation as the most profound.

Dysfunction junction: An illusion of happy domesticity is shattered in Sam Mendes’s American Beauty, with (from left) Annette Bening, Thora Birch, and Kevin Spacey (DreamWorks Pictures).

Troy’s Reality Bites monologue about his father is not the only poignant commentary on nuclear families in the film about disaffected twentysomethings. A fair amount of discussion in the film is devoted to how shy homosexual Sammy Gray (Steve Zahn) will reveal his sexual identity to his conservative mother, a quandary faced by vast numbers of Gen Xers who tested their parents’ acceptance of alternative lifestyles. Viewers don’t see the revelation scene, but they do see its aftermath: Sammy speaks directly to the camera, which director Ben Stiller uses to represent the camera of fledgling documentarian Lelaina (Winona Ryder), and nervously explains that his announcement was met with anger, not acceptance.

SAMMY: I came out to her. She’s still a little bit upset. But you know, I think the real reason I’ve been celibate for so long isn’t really because I’m that terrified of the big “A” [AIDS]. I can’t really start my life without being honest about who I am…. I want to feel miserable and happy and I mean and I want—I want to be let back in the house.

Sammy is shunned because he’s different, and his pain echoes the feelings of abandonment that any child distanced from his or her parent feels. This feeling of familial disenfranchisement reverberates throughout Jodie Foster’s Little Man Tate, during which a genius child is separated from his mother, and Home for the Holidays, which depicts a gay character as the black sheep of his family. Films such as Foster’s and Reality Bites explore what happens when a child is cleaved from his or her family, and generally offer the homily that perseverance and love can nurture acceptance. For all their images of dysfunction, these films convey a vision of familial love conquering all—or at least surmounting the biggest obstacles separating relatives.

Stephen Soderbergh offered a unique take on the forces that bind and sever family members in his gorgeously realized period piece, King of the Hill. Adapted from A. E. Hotchner’s memoir of growing up in Depression-era St. Louis, the picture concerns a resourceful youth named Aaron Kurlander (Jesse Bradford). In quick succession, his tight but struggling family is divided: His mother (Lisa Eichorn), develops tuberculosis and is sent to higher ground for a cure; his younger brother (Cameron Boyd) is sent to live with relatives because the family can’t afford to feed two children; and finally his father (Jeroen Krabbé) departs to work as a traveling salesman. Aaron’s reaction upon being left alone is utterly credible: He approaches his solitude as an adventure, even as sadness about being abandoned rises in his soul.

Joining forces with his older friend, Lester (Adrien Brody), Aaron enjoys a series of exploits that make him feel like a young outlaw, but soon even Lester is separated from Aaron. While these events are germane within the Depression-era story line—and are in fact fictionalizations of Hotchner’s own youth—they have a special meaning within the context of Gen-X cinema. The rifts that split Aaron’s family have the same effect that divorce, war deaths, and other misfortunes had on families throughout the 1960s and 1970s, so Aaron’s reactions resonate with the unwelcome leaps into maturity that so many Gen Xers were forced to take during their youths. Little short of death and disease makes a kid grow up faster than a divorce, because the shock of losing the security of family, combined with the horror of seeing parents fight, often forcibly transforms children from the nurtured to the nurturing.

Therefore, the manner in which Aaron becomes his own parent, albeit only for a time, can be seen as a metaphor for any child shunted into premature adulthood. Accordingly, the ingenuity that he displays in bringing his family back together at the end of the film is a powerful illustration of how even the youngest members of a family can have a potent effect on their home environment. The fact that Aaron never truly entertains notions of living on his own, but rather keeps his eyes on the prize of rebuilding his nuclear family, accentuates the timeless concept that individuals draw their strength from the warmth of family. The film also speaks to the essential Gen-X concept of the importance of surrogate families. During the stretch of the picture that Aaron spends totally separated from his real family, he develops a support group including Lester, a sympathetic teacher, and colorful neighbors living in his building.

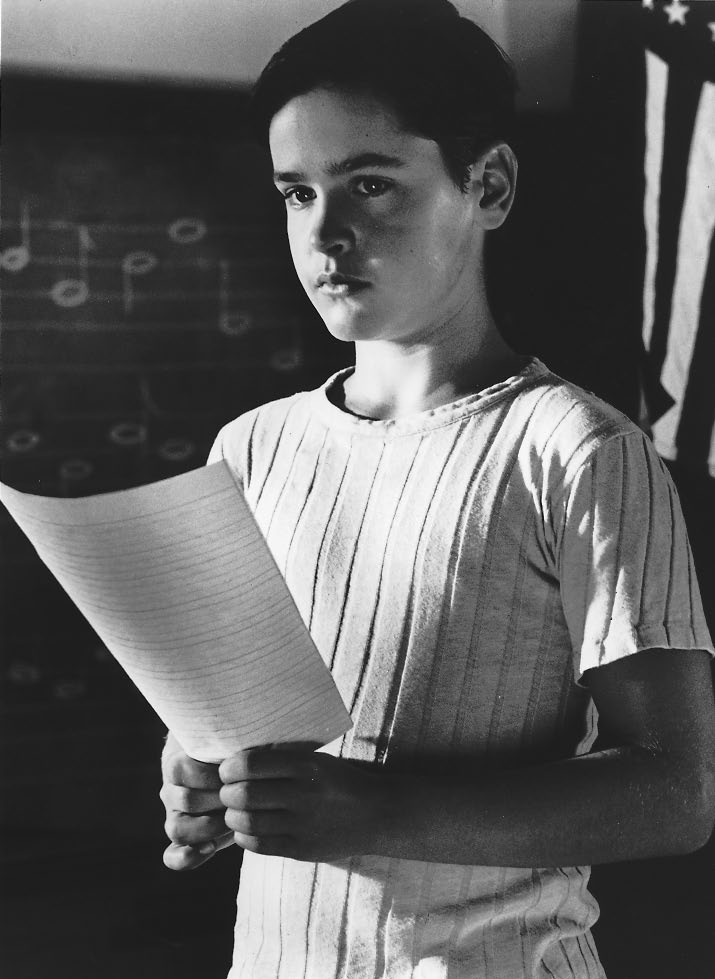

King of the Hill is about family, but even more than that, it’s about imagination. The film’s first image shows Aaron spinning a fantastic tale about a friendship with legendary aviator Charles Lindbergh. His deadpan fabrication flies over the heads of his classmates, but enchants his teacher; later, Aaron’s ability to imagine a world that’s brighter and more comforting than the real one is the skill that helps him survive his darkest moments. Key scenes show that his mother nurtures Aaron’s imagination by listening to stories he makes up at night, and this idea—of how children, and by extension adults, grow by applying their creativity to work, play, and life in general—is another one that has received memorable treatment by Gen-X directors.

Themes pertaining to the family have received significant treatment in numerous other Gen-X films, of course. Edward Burns’s gentle character pictures, including the well-received indie film The Brothers McMullen, are old-fashioned stories revolving around the trials and tribulations of such conventional units as an Irish-Catholic family. Ted Demme’s Beautiful Girls depicts how a young adult raised among blue-collar friends reacts to his old gang when he returns to his hometown older and wiser. John Singleton’s morality tale about life in South Central Los Angeles, Boyz N the Hood, shows a character caught between the conflicting guidance of a strong father and the surrogate unit comprising his friends.

Despite the turmoil that beset the family throughout Generation X’s formative years, some filmmakers from this generation have made loving odes to the power of blood ties: Robert Rodriguez’s popular fantasy Spy Kids, about a pair of preteens who use James Bond-style gadgets to rescue their loving parents from a criminal mastermind, puts forth such an unquestioning picture of familial devotion that it’s a bracing alternative to the pain that characterizes most Gen-X depictions of home life.

Movies about education become cloying when filmmakers hammer viewers with the same lessons that characters in the picture are learning, and an example of this pitfall is John Singleton’s ambitious sophomore film, Higher Learning. After making a splash with Boyz N the Hood, a smartly constructed parable, the gifted young director tackled the amorphous subject of the changes people experience in college. While his choice to treat the subject matter seriously was a welcome change of pace after years of insulting Animal House knock-offs, Singleton filled Higher Learning with suffocating piousness.

All by myself: Given the number of Gen Xers touched by divorce, movies such as Steven Soderbergh’s King of the Hill, with Jesse Bradford as a Depression-era youth who has to fend for himself, are especially poignant (Gramercy Pictures).

The picture follows three archetypal undergraduates during their first year at college, when each encounters a crisis. The black track star (Omar Epps) discovers that African-American athletes are treated like commodities by college sports programs; the pretty blonde from the suburbs (Kristy Swanson) dabbles in sexual experimentation with male and female partners; the impressionable white misfit (Michael Rappaport) gets recruited into a group of racist skinheads. In some of the story lines, an adult mentor provides portentous commentary at various steps along the journey; in others, contemporaries speak with precocious maturity. All of the vignettes are weighted down with the maddeningly obvious assertion that true learning often occurs outside the classroom, as well as the message that learning tolerance is among the most important steps in becoming a responsible adult.

A more effective movie about education, Jodie Foster’s Little Man Tate, depicts a troubled time in the relationship between young genius Fred Tate (Adam Hann-Byrd) and his working-class mother, Dede Tate (played by Foster). The third important figure in this dynamic is educator Jane Grierson (Dianne Wiest), who persuades Dede that her son should be put in a special environment that stimulates his precocious intellect. The most heartbreaking stretch of the film occurs when Fred moves in with his educational benefactor, leaving his mother alone; the subtext to this sequence is that Jane thinks Dede isn’t intelligent enough to guide a genius’s education. Despite Jane’s valiant attempt to provide a comfortable home for her young charge, she only knows how to nurture the boy’s brain, not his heart. The separation wreaks havoc on the boy, who intentionally subverts his education to force a reunion with his mother, so the film’s ultimate message is that a loving environment stimulates greater growth than a purely intellectual one. (The film also is a rare example of a Gen-X director depicting a failed attempt to create a surrogate family.)

A similar message is put across in Good Will Hunting, written by and starring Gen Xers Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. The Oscar-winning picture follows Will Hunting (Damon), an angry, working-class Boston youth, through the journey that begins when Harvard math professor Gerald Lambeau (Stellan Skarsgård) discovers the boy’s mathematical genius. The prodigy just wants to enjoy an average life with his drinking buddies, but trouble with the law forces him to accept Gerald’s tutelage—and to undergo therapy sessions with gruff but empathetic shrink Sean Maguire (Robin Williams). The entertaining, sentimental picture examines whether Will is better served by a life of the mind or the humbler life he desires, and after much onscreen soul-searching, Will makes a choice that echoes the end of Little Man Tate: He abandons a lucrative opportunity to exploit his intelligence, instead choosing to pursue human warmth, specifically the love of a pretty Harvard coed.

Both Little Man Tate and Good Will Hunting offer the crowd-pleasing idea that love has a stronger pull than intellectualism, and though Tate tries to present a balance in which the title character is nurtured both emotionally and intellectually, the films can be read broadly as criticisms of excessive education. While neither picture goes so far as to say that education harms people, both make the somewhat obvious assertion that people need to find which level of education suits them as individuals. This assertion is interesting for two reasons.

First is the fact that Gen Xers are often referred to as a generation with too much education in impractical matters and not enough in practical ones. This widespread stereotype is rooted in facts that bear upon only an affluent, entitled segment of Generation X—those members of the generation who can spend several comfortable years in the womb of college because they don’t need to hurry into the workplace—but it is propagated by the images of Gen Xers shown in films and television. These fictional Gen Xers speak, as has been shown, in an idiom informed by over-saturation in popular culture, a form of excessive education.

All about my mother: Celebrated actress Jodie Foster’s directorial efforts include Little Man Tate, featuring Foster as the mother of a young genius (Adam Hann-Byrd) (Orion Pictures).

Therefore, if Gen Xers Foster, Damon, and Affleck indeed meant to put across a cautionary message about education, that message could be interpreted as a reaction to the information with which Gen Xers have been bombarded since youth. In that case, the message common to Little Man Tate and Good Will Hunting is more interesting than a knee-jerk condemnation of soul-numbing educators and soulless educational institutions. It is a pained cry for relief from the hurricane of soundbites, infotainment, and junk culture in which Gen Xers have been swept up since childhood.

Interestingly, author Geoffrey T. Holtz noted that educational standards suffered a marked decline during key years of Generation X’s youth. In Welcome to the Jungle, he reported that experiments with hands-off teaching (in which students were given greater authority to determine their own curriculum) and changes in grading policies (in which failing grades were eliminated, or at least used sparingly, to nurture students’ feelings of self-worth) compromised the quality of schooling that Gen Xers received. Additionally, Holtz noted, the parents of Gen Xers experienced a dangerous shift in attitudes that led them to fight school funding more vigorously in the 1970s and beyond than in any previous time. As Holtz wrote:

One paradox of stressing self-esteem came to light in an international math test given to thirteen-year-olds in 1988. American students were dead last among the nations who took the test, yet they led the pack in considering themselves “good at mathematics.” Korean children, only 23 percent of whom judged themselves good math students, also happened to be the highest-scoring students. [Gen Xers] may have developed some of that high self-esteem—perhaps arrogance is a more appropriate term—in school. Unfortunately, what they needed to learn may have been a little humility, and a lot more math.1

Such trends created an atmosphere in which respect for schools was greatly lessened, as seen in the contempt for educators and educational institutions that permeates such youth films as Animal House, Fast Times at Ridgemont High, The Breakfast Club, and Revenge of the Nerds, all of which became hits thanks to the buying power of Gen-X moviegoers. The anti-teacher attitude also appeared in such popular rock songs as Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out” and Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall,” both of which were radio staples during Generation X’s youth. This metaphor of classroom-as-battleground was the inspiration for several Gen-X pictures, beginning with Keith Gordon’s 1988 drama The Chocolate War, in which a strong-willed student and the inflexible headmaster of a private school challenged each other throughout a vigorous battle for dominance over their shared environs.

Probably the most entertaining Gen-X spin on educational issues is Wes Anderson’s Rushmore, a satire so cheeky that it almost drowns in its own self-satisfied wit. Set at the prestigious Rushmore Academy, the picture tracks the exploits of one Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), a parody of every overachiever ever encountered in fiction and reality. The high schooler participates in a ridiculous number of extracurricular activities, but not because he excels in them; in fact, he’s stretched so far past his intellectual capacity that he’s in danger of flunking out of school.

Max isn’t daunted by his academic problems, however. During the course of the movie, he plunges deep into work with groups including the Max Fischer Players, a pompously named theater troupe that makes overblown stage productions such as a Vietnam drama complete with faux helicopters and explosions. Max also attempts to spark a romance with a pretty young teacher, Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams). His rival for her affections is Herman Blume (Bill Murray), a school benefactor as cynical as Max is optimistic. Just as Max lives beyond his means academically and artistically, he tries to inhabit a romantic identity beyond his years. He overreaches in every possible way, and his occasional successes owe more to perseverance and dirty tricks than aptitude.

Therefore, it’s possible to interpret Max as the ultimate manifestation of the animosity toward education that recurs in several Gen-X films. Max benefits not from traditional education, but from creating his own educational opportunities. Seen through conventional eyes, Max is a failure: His grades are poor, he doesn’t blend into the mainstream of the student body, and he doesn’t respect authority. But from a nonconventional standpoint, Max is a smashing success: He expresses himself without inhibition, is on his way to becoming a fully realized individual, and thinks for himself. Like the geniuses in Little Man Tate and Good Will Hunting, faux genius Max defies the stagnant, cold ideals of traditional education and makes his own path.

Yet on a poignant level, Max’s academic shortcomings amplify the danger of unchecked freethinking: By choosing to disregard the mainstream, Max diminishes his social opportunities and alienates many of his peers. The price for his individualism is isolation. The makers of Rushmore find a way to let Max have his cake and eat it too, albeit with a bittersweet aftertaste: Max loses Rosemary to Herman, but forms a romantic bond with a geeky schoolmate, essentially lowering his expectations sufficiently to embrace reality.

Max closely resembles another memorable Gen-X protagonist, Nebraska high schooler Tracy Flick, played to perfection by Reese Witherspoon in Alexander Payne’s scathing Election. Tracy is an intense overachiever who joins every organization, has an answer for every question in every class, and, despite being almost pathologically upbeat, never seems to have any fun. Most of the people in Tracy’s school pay her no mind, accepting her as part of the scenery. But one of her teachers, Jim McAllister (Matthew Broderick), finds her relentless ambition distasteful. And when it seems that Tracy is poised to coast past another obstacle by running unopposed for student-body president, he decides to take her down a peg—a biting dramatization of the antagonism that many Gen Xers perceive in their relationship with educators.

Payne uses a fittingly brash storytelling style throughout Election. During Tracy’s first scene, he freezes a close-up so that her face is contorted in mid-speech, then leaves the unflattering shot onscreen while Jim’s voice-over describes Tracy’s history. The director’s funniest touch is employing tribal voices as a musical leitmotif whenever Tracy fears that events are spinning beyond her control, a neat trick revealing the animal instincts burning beneath her cool demeanor. Tracy represents ambition unaccompanied by compassion (and, by extension, education unaccompanied by compassion), so she’s part of the wonderfully dark skewering of “heartland values” that distinguishes Omaha-born Payne’s work.

A final, albeit much more superficial, Gen-X reaction to education is seen in the films written and/or directed by Kevin Williamson. In The Faculty, which Williamson wrote, and Teaching Mrs. Tingle, which he wrote and directed, high school educators are depicted as monstrous villains. Both are escapist fantasies designed to help youths purge the angst they feel about their daily “tormentors,” and both are aftershocks of the high school films that were popular in the 1980s. Unfortunately, The Faculty and Teaching Mrs. Tingle are silly, bloody thrill rides, featuring little of lasting substance.