DISASTER AND VICTORY IN THE SOUTH SEAS : LORD ANSON’S TERRIBLE VOYAGE

ON MARCH 7, 1741, after weeks of fine sailing, an English squadron cruising around Cape Horn, the southern tip of South America, was buffeted by erratic gusts of wind from the south, the forerunner of a terrible storm. The sun was slowly enveloped in cloud and mist, the waves grew ponderous and dark, and the wind rose to a ferocious moan. The autumn gales of the southern hemisphere had begun. It was, according to the official chronicle of George Anson’s expedition, “the last cheerful day that the greatest part of us would ever live to enjoy.”

ON MARCH 7, 1741, after weeks of fine sailing, an English squadron cruising around Cape Horn, the southern tip of South America, was buffeted by erratic gusts of wind from the south, the forerunner of a terrible storm. The sun was slowly enveloped in cloud and mist, the waves grew ponderous and dark, and the wind rose to a ferocious moan. The autumn gales of the southern hemisphere had begun. It was, according to the official chronicle of George Anson’s expedition, “the last cheerful day that the greatest part of us would ever live to enjoy.”For the men of those five warships and one sloop, it was the beginning of a three-month battle for their lives. The ships struggled southwest against the incessant wind and surging currents that threatened to drag them back east onto the jagged, rock-bound coast. Winds tore at the rigging from erratic angles; purple-and-black clouds rolled across the sky, making navigation impossible;

and ragged froth was whipped across the deck. The ships pitched in the wild sea, water pouring in the hatches as they pounded into rising waves. For weeks the tempest raged, keeping them at sea far longer than they had planned. The ships were spun about uncontrollably, occasionally teetering on the precipice of the curling tongue of a “mountainous overgrown sea” before plunging into the heaving valleys between the waves, the timbers shuddering and groaning under the impact. “The fury of all the storms which we had hitherto encountered seemed to be combined,” reads the chronicle of the voyage, “and to have conspired our destruction.”

As the storms increased in severity beyond the wildest imaginings of the mariners, who were already enfeebled by dysentery and typhus, scurvy began to spread its ugly tendrils. Just when they needed their strength the most to battle the furious storm, they grew weaker by the day. The lower decks were awash with sickly bodily fluids, and men lay prostrate in the slime, sluicing about as the ships bucked and spun in the gale. Several of the oldest sailors were horrified when old battle wounds sustained decades earlier began to bleed anew and shattered leg bones separated again, causing bewilderment and excruciating pain. “This disease … so particularly destructive to us, is surely the most singular and unaccountable of any that affects the human body. For its symptoms are inconstant and innumerable, and its progress and effects extremely irregular.” At first only a third of them lay ill, swaying in their hammocks in the reeking bowels of the ship. Soon their teeth became wobbly, their gums turned black, and they lost the will to man the ship. “Some lost their Senses, some had their sinews contracted in such a Manner as to draw their Limbs close to their Thyghs, and some rotted away.”

Seldom did a day pass that a man did not expire in the dim, fetid hold where their hammocks were strung up. They perished with agony frozen on their ghastly countenances. The log of the largest warship, the Centurion, records death from scurvy as a routine entry, often several per day. April 18: “Richard Dolby and Robert Hood seamen and William Thompson marine deceased.” April 28: “Robert Pierce, John Mell, seamen deceased.” May 13: “Arthur James, Vernon Head seamen deceased. The latter died suddenly.” Finally, after a month and a half of daily deaths, even their names were too much bother to write down in the ship’s log. May 28: “Two more seamen died and three soldiers.” Some of the dead men were sewn into their hammocks and pitched overboard, but as the disease progressed, the living mariners became too enfeebled to deal with the dead. Many were tumbled into the hold, where they stiffened and washed about, while others lay stranded on the deck, lurching from side to side with the motion of the ship. In the month of April, the Centurion lost forty-three men to scurvy, and in May, as the ship turned north and the men hoped that with milder weather, “its [scurvy’s] malignity would abate,” they lost perhaps twice that number. The squadron was blown about the wind-whipped ocean, with barely a handful of days of stable weather, until the end of May, when the storm finally eased and the skies momentarily cleared.

Anson’s ship off South America.

During the terrible ordeal two of the ships had abandoned all hope of pressing around the Horn and retreated to the Atlantic, while a third was in serious trouble. Containing a great number of invalids and fever-racked patients even before scurvy broke out, the Wager was further disabled when the storm snapped her mizzen mast, leaving her with a shattered stump incapable of holding much sail. As the ship picked its way north along the jagged and desolate west coast of Chile, storms continued to rattle her, scurvy took most of the men out of commission, and the ship was in danger of foundering. On the fourteenth of May 1741, the Wager struck the rocky coast and was torn asunder, with many perishing horribly because they were too weak to scramble ashore against the rumbling surf.

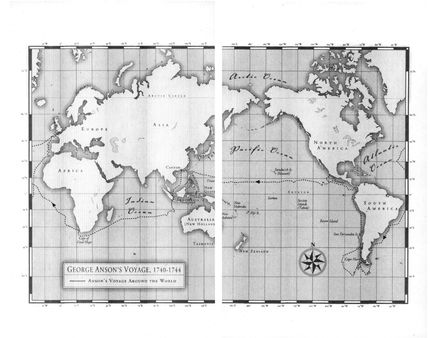

Commodore George Anson led a squadron of ships on a four-year voyage that historians have described as the worst medical disaster ever at sea. Most of Anson’s crew were killed by scurvy: only one of the five warships that departed England in 1741 made it home.

In late 1739, England and Spain had declared war over trade and sovereignty rights in the Caribbean, and George Anson, an as-yet-undistinguished officer of middle years, who had fought as a young man against the Spanish at the Battle of Passaro in 1718 and had commanded ships in trade-protection duties off the coast of South Carolina and Guinea, was commissioned to lead a six-ship fleet to the South Seas, the Pacific coast of South America. His mission was bold and unprecedented for the Royal Navy. After arriving in the Pacific, he was instructed to “do your best to annoy and distress the Spaniards … by taking, sinking, burning, or otherwise destroying all their ships and vessels that you shall meet with.” He was also commissioned to attack a few towns and, most important, to capture the Manila treasure galleon, the Spanish ship that hauled silver between Acapulco and the Philippines. Because of its immense value it was known as “the Prize of All the Oceans,” and it had been captured twice before by English privateers (Thomas Cavendish in 1587 and Woodes Rogers in 1709), but never in an official Royal Navy operation. Anson’s expedition was a dangerous and important military manoeuvre designed to strike at the heart of Spanish trade and commerce.

To accomplish this mission, Anson was given command of five two-decked ships of the line, one single-decked sloop, and two small supply vessels. Although Anson’s fleet did not leave Spithead, England, until mid-September, it began assembling in February 1740. The warships consisted of the massive flagship Centurion, at 1,005 tons and 60 guns; the Gloucester and the Severn, each at 853 tons and 50 guns; the Pearl and the Wager, at 600 tons with 40 guns and 24 guns, respectively; and the 200-ton sloop Tryal. The ships needed repairs to the masts and sails, and reorganized cabins and lower decks to accommodate the increased number of sailors and marines required for the mission. For months the ships were delayed in the dockyards, which were already overcrowded as the navy hurriedly mobilized dozens of ships for the impending war.

Finding the thousands of able-bodied sailors and marines proved to be an even more daunting task than repairing the ships. While the dockyards were working around the clock renovating aging ships, and the victuallers were furiously busy trying to gather provisions, press gangs prowled the warrens of dockside towns for new recruits. But the overcrowding helped the spread of contagious diseases such as typhus and dysentery, and sickness was wreaking terrible havoc in the seaside towns. The navy’s sick list was expanding faster than the press gangs could find or capture new recruits, so the tally of able-bodied mariners actually decreased throughout the summer of 1740. The shortage of manpower rendered about a third of the navy’s ships useless. Malnutrition was rife in the spring of 1740 because of a particularly long and cruel winter, and the cost of fresh food was unusually high, further compounding the problem. Many of even the healthiest members of Anson’s crew hadn’t eaten fresh vegetables or fruits in significant quantities for months, perhaps not since the fall harvest. They were not healthy men, even the best of them.

Anson needed around two thousand sailors, and by July 1740, though most of the major repairs had been completed on the ships, he was still several hundred short. He was anxious to depart as soon as possible, in order to have time to clear Cape Horn before the storm season began in March. But finding additional sailors and obtaining the final supplies were a bureaucratic nightmare, and he must have despaired of ever sailing. By early August he still could not fill his ships, and the Admiralty decided to clear out the pensioners from Chelsea Hospital and make them available for the mission. These five hundred men were veterans of earlier wars who had been maimed or driven mad, or who were too infirm to be on active duty. Many of them were over sixty years old, some over seventy. Some were incapable of walking and were carried aboard the ships on stretchers, begging to be released back to the hospital but unable to return themselves. They were, according to Anson, the most

“crazy and infirm” the hospital had to offer, and entirely unfit for active service.

Anson was appalled, referring to them as “the most decrepit and miserable objects … much fitter for an infirmary than for any military duty.” Offended and disgusted, he later wrote in the official account of his voyage that “without seeing the face of an enemy, or in the least promoting the success of the enterprise they were engaged in, they would in all probability uselessly perish by lingering and painful diseases; and this too, after they had spent the activity and strength of their youth in their country’s service.” The Admiralty was attempting to clear out the hospitals before the war to make way for the anticipated new wounded who would soon be arriving; certainly the navy must have been aware that very few of the invalids would be fit for the rigours of sea. In fact, only half of the released men arrived at Anson’s ships; most of those who could walk had fled certain death aboard the fleet for uncertain but probable death in the slums of Portsmouth. Some of the deserters later applied at the hospital to reinstate their pensions and were mercifully received back. By the time the ships had reached western Chile, within a year of sailing, virtually all of the pensioners on board had perished, the bulk of them during the scurvy epidemic as they battled the storms of the Horn, fulfilling Anson’s dire prediction. Entirely useless to the mission, the “aged and diseased detachment” contributed to overcrowding on the ships at the start of the voyage, which in turn helped to spread other diseases that killed many able-bodied seamen.

Anson was further dismayed when he beheld the contingent of marines who arrived to bolster his ship’s company. Nearly all of them were young, frightened raw recruits who were “useless by their ignorance of their duty,” and who had not “been so far trained, as to be permitted to fire.” The bulk of them were already sick with fever or dysentery and were soon clogging up the holds of the ships, deliriously sweating in misery in the dank depths. As it had with the

invalids, scurvy latched on to the marines with particular virulence and killed most of them; by the time the squadron reached Juan Fernandez Island, over 80 percent of them had perished. Tellingly, the Wager, the ship that was driven aground on the coast of Chile, contained the greatest number of invalids and marines; they outnumbered the able-bodied crew by 50 percent.

By late August the invalids had been settled aboard, the vast quantity of provisions needed for so large a crew had been secured, and the most grievous deficiencies in the ships’ structures had been repaired. The squadron was ready to sally forth on its dangerous mission. It must have been exciting news indeed to many of the men who for nearly half a year had been living aboard the stationary vessels, subsisting on ship’s rations enlivened by the occasional treat of fresh potatoes, leeks, or cabbage. Unfortunately, unfavourable winds kept them tethered to port for several more weeks, and then, in early September, Anson was unexpectedly ordered to chaperone a huge convoy of merchant and transport ships bound for the West Indies and North America. It was a tedious and slow business as 152 lumbering vessels clustered around Anson’s squadron and puttered west. By the time Anson’s fleet veered south to Madeira, off the southwest coast of Portugal, winds had again turned against him. The two-week voyage took nearly six weeks, and he did not spy the island until the end of October. Already men were dying aboard the ships, though scurvy had not yet manifested itself.

Because the squadron had remained “in port” for months before actually sailing, the sailors on board were eating ship’s rations nearly devoid of fresh vegetables and fruit. Being in port did not have the same meaning for the crew of an eighteenth-century warship as it does for a modern traveller. Warships in port were anchored a considerable distance offshore for weeks or even months at a time, while the crew remained on board. They would have had little access to fresh foods and might not have been granted shore leave, except to join a press gang hunting for new recruits. Furthermore, the cost of food for so large a company was so expensive that quality suffered. So it was hardly surprising, and indeed Anson does not appear to have been much surprised, that disease, and particularly scurvy, had destroyed the vast bulk of his sailors, and hastened the wreck of the Wager, before he encountered a single Spanish ship. The Admiralty had ordered the standard antiscorbutic cures of the day: a daily draft of two ounces of vinegar, elixir of vitriol (sulphuric acid mixed with alcohol), and a potent patent medicine known as Ward’s Drop and Pill (a viciously strong purgative and diuretic that many sailors took as the ships struggled around Cape Horn). Anson “gave a quantity of them to the surgeon, for such of the sick people as were willing to take them; several did so; though I know of none who believed they were of any service to them.” Joshua Ward’s quack medication contributed to the unsanitary squalor belowdecks, weakening the men and hastening the death of those who might otherwise have survived.

Because of the size of the expedition and the extraordinary length of time it took to organize and outfit it, French agents in London passed word to the Spanish, who hastily compiled their own squadron to chase Anson and prevent him from taking the fabulous treasure ship. Admiral Don José Pizarro led five warships from Santander in October 1740 to intercept Anson and thwart his ambitions. There would be two fleets of battleships chasing each other around the world.

Anson’s squadron spent several months crossing the Atlantic and did not reach the coast of South America until December. Although they put into port on the island of St. Catherine’s, off the coast of Brazil, for about a month, the men remained shipboard for most of this time. On St. Catherine’s, “fruits and vegetables of all climates thrive here, almost without culture, and are to be procured in great plenty; so that here is no want of pine-apples, peaches, grapes, oranges, lemons, citrons, melons, apricots, nor plantains.” Anson

also purchased some onions and potatoes. But the produce was expensive because of the influence of the island’s Portuguese governor, who placed “sentinels at all the avenues, to prevent the people from selling us any refreshments, except at such exorbitant rates as we could not afford to give.” Anson and his pursers purchased only small quantities of these delicacies for the crew. Many of the sailors aboard ship, already sickly before coming aboard, had now gone at least six months with very little in the way of fresh foods that would have held scurvy at bay. Just as they were about to enter the most dangerous waters of the voyage, perhaps the most dangerous waters anywhere in the world—the notoriously fickle and turbulent passage round the Horn of South America—the crew were at their weakest and the seeds of scurvy began to germinate.

While Anson’s ships ploughed around Cape Horn, heaving bodies overboard almost daily as they went, the Spanish squadron under Pizarro attempted to intercept them first at Madeira and then along the coast of South America. The Spanish fleet also attempted to round the Horn into the Pacific Ocean, rushing to be ahead of Anson and lie in wait off the western coast of South America. Pizarro’s five ships had a gun total of 284, greater than Anson’s six ships at 220. It was a formidable battle fleet that included the flagship Asia, of perhaps 1,200 tons and 66 guns; the Guipuscoa, of similar tonnage and 74 guns; the Hermiona, of around 850 to 900 tons and 54 guns; the Espertinza, of about 800 tons and 50 guns; and the St. Estevan, of about 600 tons and 40 guns. In total Pizarro commanded about 2,700 sailors; in addition, several hundred foot soldiers had been sent to reinforce garrisons in Peru. Although the Spanish ships were proportionately larger than the English ships, they too were extremely crowded for such a long voyage. They were also poorly provisioned. In their haste to catch up to Anson’s fleet, they had rushed out of port in Spain provisioned for only four months, with instructions to obtain more food and water

in Buenos Aires. Upon hearing a rumour that Anson lay in harbour at St. Catherine’s, Pizarro rushed his ships from Buenos Aires before they were reprovisioned so he could try to sail around Cape Horn first.

The same storms that beset Anson’s squadron in March 1741 also lashed the Spanish fleet, sucking the Hermiona and at least five hundred men beneath the waves in the terrible tempest. The Guipuscoa, carrying at least seven hundred men, was likewise battered by the storm and sent grinding into the rocky coast, killing half of them. The other three ships were violently sucked back east into the Atlantic and eventually rendezvoused at Montevideo, Uruguay, at the River Plata, in May, about the same time that the ruined remnants of Anson’s squadron limped into Juan Fernandez Island. Pizarro’s squadron had fared even worse. Not only did the mariners have no fresh foods, but they had been placed on starvation rations when the four-month supply of ship’s provisions was depleted during their months-long battle with the storms of Cape Horn. There are no exact records of whether scurvy was rampant on the Spanish ships, but considering the time at sea and the lack of even standard rations, it is extremely unlikely that the Spanish sailors were eating anything fresh, and unlikely that scurvy could have been avoided under the circumstances. Undoubtedly, the weakened state of the mariners contributed to the loss of the two ships. Anson later wrote, after hearing a report of the Spanish commander’s ordeal, that “they were reduced to such infinite distress, that rats, when they could be caught, were sold for four dollars a-piece.” One sailor apparently concealed the death of his brother from the others for several days, sleeping in the hammock with the decaying corpse, in order to gain the man’s meagre food allowance. More than half the crew on the three surviving ships were dead by the time they reached Montevideo.

The St. Estevan was too damaged to proceed, and the others, with split sails and snapped masts, could be only partially repaired

during the summer. The following October, in 1741, the Asia and the Esperanza again attempted Cape Horn, but they were defeated and sent back a second time. Although Anson and the English fleet had no idea of the magnitude of the Spanish disaster in the spring of 1741, they had won their first victory, albeit not through any efforts of their own, but because the conditions and provisioning of the Spanish fleet were, against all probability, worse than their own.

After rounding Cape Horn, the remaining ships of Anson’s convoy, scattered during the terrible months of storms, limped independently north towards their rendezvous on Juan Fernandez Island, a small island several hundred miles off the Chilean coast, directly west of Santiago. There they hoped to regroup and recuperate before pressing on with their mission. Men were dying of scurvy at a rate of five or six a day on the flagship alone, their bodies unceremoniously flung into the sea. The mortality rate was even higher on the other two vessels. Misfortune continued to plague them, and they did not arrive at the island until June, several weeks later than expected, because of an inability to accurately calculate their longitude and find their position at sea. As the Centurion, sailed blindly about, searching for the island, about eighty more men succumbed to scurvy.

So many men had died from scurvy rounding Cape Horn that by the time the three ships anchored in Juan Fernandez Island, the Centurion had barely seventy men capable of duty. A second ship, the Gloucester, had “thrown overboard two-thirds of their complement, and of those that remained alive scarcely any were capable of doing duty, except the officers and their servants.” And the smaller sloop Tryal likewise had buried more than half her complement, and only the captain, a lieutenant, and two sailors could “stand by the sails.” The remaining mariners wept and stared in disbelief as

they neared the distant outcropping of land. “It is scarcely credible with what eagerness and transport we viewed the shore, and with how much impatience we longed for the greens and other refreshments which were then in sight.” Although the vessels were more wrecks than ships, with torn sails dangling from snapped masts and dying men crowding the decks for a glance at the long-sought laid, the ships quietly floated into a harbour and dropped anchor as night crept upon them. Scarcely believing their deliverance, the few reasonably able-bodied men began ferrying ashore the and supplies, a task that consumed many days because of their weakened condition. Fortunately they were blessed with fair weather, because, as noted in the official report, “we could not, taking all our watches together, muster hands enough to work the ship in an emergency.” Many of the mariners who hovered at death’s door passed quietly away as soon as they were brought from the befouled interior of the ship into the clean air.

After establishing a makeshift encampment on the wooded and hilly island, they began tending to the sick and taking stock of the disaster. They were in the unknown waters adjacent to South America, officially at war with the people who inhabited the often bleak and inhospitable coasts. Although their orders called for them to boldly harass Spanish shipping, for many weeks they cowered in fear of even the smallest Spanish ship spying their encampment. They knew for certain that a Spanish battle squadron of five ships of the line had been dispatched to chase them into the Pacific, and if it spied them now, they would certainly be captured and probably killed. Although the English mariners still had two huge man-of-wars and a heavily armed sloop, there were not enough healthy men to sail a single ship into battle it the occasion arose. Anson, although a determined and optimistic man, knew that things did not look good. Somehow a naval force of great strength had been reduced to a bedraggled, tattered trio of badly damaged ships, with more than a thousand sailors already dead, mostly from scurvy, and

hundreds more weak and limping about the shore scavenging for fresh foods. The prospect of completing their mission seemed dim as men continued to perish daily for more than a week after they landed.

Fortunately, Anson and the battered remnants of his expedition found Juan Fernandez Island to be a virtual paradise where grew “almost all the vegetables esteemed for the cure of scorbutic disorders … . These vegetables with the fish and the flesh we found here, were most salutary for recovering our sick, and of no mean service to us who were well, in destroying the lurking seeds of scurvy and in restoring us to our wonted strength.” Some of the mariners reputedly shuddered and convulsed when they sank their wobbly teeth into the juicy fruit. After several months of painfully and slowly nursing themselves back to health, the remaining English sailors had recovered from their horrible ordeal and prepared to leave their island haven. But the death toll was astounding: of the approximately twelve hundred men who would have been on the three ships, only 335 remained alive. The normal ship’s complement for the Centurion alone was around five hundred, and although enough sailors remained to sail all three ships, there were not enough to both sail them and man the great guns—each of these guns had a barrel around ten feet long, weighed about two tons, and needed a crew of six to ten men to operate. The Centurion, was a sixty-gun ship, and the Gloucester was nearly as large.

In mid-September a sail was spied on the horizon. For months they had been expecting discovery by the Spaniards, either by Pizarro’s fleet or by a patrol out of Peru, and it was only good fortune that had preserved them thus far. A makeshift crew was hastily assembled and loaded aboard the Centurion, which sallied forth to take it. It proved to be a lightly armed Spanish merchant ship voyaging from Lima, Peru, to Santiago, and it was taken without resistance after a few shots were fired over its bow. From the passengers, Anson learned the frightening news that a Spanish man-of-war had

indeed been waiting for them at Juan Fernandez Island, but it had departed only days before they had arrived, believing them to have been destroyed rounding Cape Horn. Oddly, Anson’s miscalculation of longitude, which had delayed the Centurion from landing at the island for nearly two weeks and cost the lives of perhaps eighty men, may have saved the entire squadron from capture and possibly death. Anson also learned of the terrible fate of Pizarro’s fleet, the information having crossed the continent by land. He sent aboard some crew to command the captured ship and distributed the Spanish sailors amongst his ships to help sail them. During the next few months, they took several other Spanish merchant ships and stormed the small Spanish town of Paita, Peru, burning most of it to the ground. Then they sailed north to Acapulco, Mexico, searching for the Manila galleon, but they failed to encounter it. During all this time the men remained healthy and free from scurvy, probably because they frequently ate fresh provisions captured from merchant ships and plundered from shore. Before Spanish authorities could mobilize a fleet to track him down, and because merchant ships were now becoming wary after hearing news of his attacks, Anson decided to leave the Pacific coast of Spanish America. He ordered the release of the Spanish prisoners but kept the West Indians and Pacific Islanders to bolster his meagre crew.

Anson planned to spend two months crossing the Pacific to Canton, China, where the East India Company had a trading outpost. He ordered all the captured ships burned and scuttled; there were only men enough to provide a crew for the Centurion and the Gloucester. The prisoners were released near Acapulco, and the two ships, loaded with silver, gold, precious gems, and other valuable goods, headed west on May 6, 1742, late by several months for catching prime trade winds. Not surprisingly, they became becalmed, and during the dreadfully slow passage, scurvy again surfaced on the floundering ships. The surgeon and men alike were baffled because

they had been drinking good water and eating reasonably good food; the ships were also clean and uncrowded, and fresh fish were frequently caught. The ships’ logs make no mention of fresh fruits and vegetables, however. The first death occurred in the middle of the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean on July 5; and deaths continued at the rate of about five per day. Ward’s Drop and Pill needlessly weakened many of the men, and the vinegar and oil of vitriol were of course worthless.

The deaths from scurvy were as hideous and demoralizing as any ever recorded, and in mid-August Anson ordered the Gloucester abandoned because there were not enough men to repair the damaged masts and rigging. Of the Gloucester’s remaining ninety-seven men, only twenty-seven, including eleven young boys, could still stand on deck. The scurvy-ridden mariners were hoisted from the lower decks in nets and transferred to the ship’s small boat, while the others broke into the liquor cabin and drank themselves silly before torching the ship. The hulk burned all night and then exploded at about 6 a.m., when the flames reached the powder magazine. “Thus ended the Gloucester,” wrote one of the warrant officers, “a ship justly esteemed the beauty of the English navy.” Aboard the Centurion, the sole remaining ship, the wretched crew continued to drop off “like rotten sheep” at the rate of ten per day. The ship was heavily laden with all the captured goods and had sprung a leak, but the crew were too weak to both sail the ship and repair the damage. Anson himself, once the aloof commodore of a proud fleet, now laboured at the pumps alongside the few able-bodied men who remained. Although the ship’s log showed that they had sailed more than sixty-five hundred miles west from Acapulco, land was still nowhere in sight.

It was not until the end of August that the mariners spied the island of Tinian, in the Marianas chain. “I really believe,” wrote Philip Saumarez, a lieutenant aboard the Centurion, that “had we stayed ten days longer at sea we should have lost the ship for want of

men to navigate her.” When the crippled ship put in to harbour, Anson personally helped row the dying ashore. The able-bodied cut open juicy oranges and squeezed the life-saving juice into the ruined mouths of the dying sailors. Tinian offered “cattle, hogs, lemons and oranges, which was the only treasure which we then wanted.” It was not until the end of October that the men had recovered and the ship was reasonably repaired. Only a few hundred remained alive. Lieutenant Saumarez offered his own unprofessional opinion that scurvy “expresses itself in such dreadful symptoms as are scarce credible … . Nor can all the physicians, with all their materia medica, find a remedy for it.” Nothing, he claimed, was “equal to the smell of a turf of grass or a dish of greens.” Before leaving the island, Anson ordered the hold of the ship stuffed with oranges.

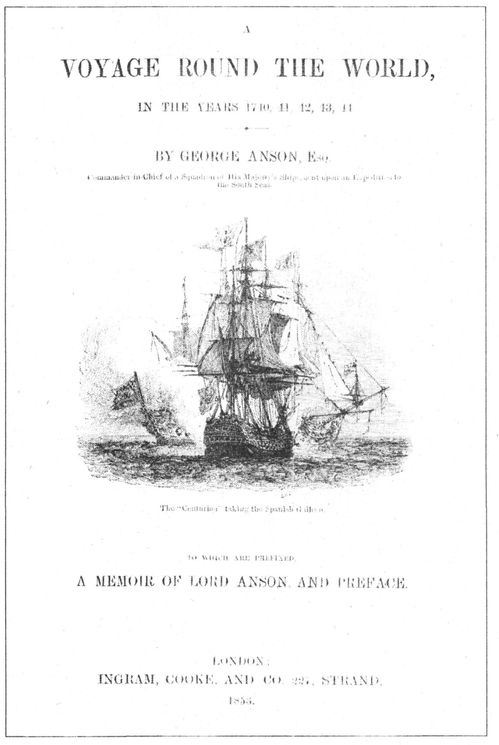

The bruised ship was barely seaworthy and limped into port at Macao, near Canton. After an interminable delay and much bureaucratic annoyance, Anson was able to secure help and supplies to properly repair the Centurion. In April 1743, he departed, still determined after all the hardships and danger, to attack the Manila galleon. With only 227 sailors on the Centurion, including several dozen young boys and some Dutch and Lascar seamen taken aboard at Macao, it was a foolhardy gamble. “All of us had the strongest apprehensions (and those not ill-founded),” wrote Anson, “either of drying of the scurvy, or of perishing with the ship, which, for want of hands to work her pumps, might in short time be expected to founder.” Yet on the twentieth of June, 1743, in an unspectacular battle where the galleon struck her colours after ninety minutes, Anson took the Covadonga, the “Prize of all the Oceans,” just off Cape Espíritu Santo in the Philippines. Only three of his men were killed in the battle and seventeen wounded, while sixty-seven were killed aboard the Covadonga and eighty-seven wounded. Although the Covadonga was a larger ship than the Centurion, and had a far larger crew, she was not a warship and her sailors were not warriors. Anson sailed both ships back to Macao, where the prisoners were discharged and the empty galleon sold.

The title page to Anson’s A Voyage Round the World showing the smaller Centurion blasting away at the Spanish treasure galleon Covadonga. Despite a sickly and short-handed crew, Anson was victorious and he and several hundred survivors became fabulously rich.

The total haul from the exploit was tremendous, and when Anson and his remaining men returned to England, they paraded through the streets of London, in thirty-two heavily laden wagons, two to three million pounds of bullion. Anson’s feat was the one shining success in a war that had seen few actions worthy of celebration. It was praised as a great victory despite the horrendous loss of life. Not only did the few hundred survivors become inordinately rich, but Anson, who received the lion’s share of the booty, became fabulously wealthy and his reputation was made. He was quickly promoted to Admiral of the Blue and, in 1751, First Lord of the Admiralty, a position he held until his death in 1762, and through which he tried to introduce progressive changes to shipboard hygiene and encourage scurvy research. Only after the jubilation faded did the sobering reality of the number of lives lost temper the wild celebrations. No more than a few hundred of the two thousand men who had departed four years earlier survived. Of those who did survive, many were maimed, and the officers in particular claimed to have never regained their health entirely.

The end result of Anson’s voyage, other than the usual riches and boost to national pride, was the beginning of a golden age of scurvy research in England. The voyage raised public awareness of the social cost of scurvy everyone now knew that more British sailors routinely died from scurvy than from shipwreck, storms, all other diseases, and enemy action combined. Furthermore, ships like the Gloucester, which Anson was forced to abandon in the Pacific when scurvy had killed so many of his men, were outrageously expensive. It was becoming apparent that even if the Admiralty placed little value on the lives of the sailors, it did place value on its ships. When too many men died too quickly far from home waters, valuable ships had to be abandoned. No matter how grand a ship was, it was useless without sailors and marines to properly sail it.

Throughout the eighteenth century the danger posed by the wars with the French, the Seven Years’ War, the War of American Independence, the French Revolution, and later Napoleon presented the greatest threat to England since the Spanish Armada two centuries earlier. Liberating the Royal Navy from the hobbling dominion of scurvy was paramount for national security. In the decades following Anson’s voyage, there were perhaps a dozen different physicians who wrote about the disease and its cure. This compared to the handful of new ideas offered up in the previous two centuries. Despite the growing fashion for research into naval diseases, however, scurvy remained as great a mystery as ever for decades after Anson’s voyage. Unravelling the intertwined threads of the scurvy problem meant tackling the very foundation of medical reasoning, for it in itself was a serious impediment to the advancement of new ideas, unsuited as it was to the problems and ailments of the new age being ushered in by the Industrial Revolution.