AN OUNCE OF PREVENTION : JAMES LIND AND THE SALISBURY EXPERIMENT

SOCIAL HIERARCHY aboard Royal Navy ships was rigid and strict. A ship’s roster listed all hands, their positions and duties, and their pay. At the top, a virtual dictator with control literally over life and death, was the captain. He lived alone in a commodious private cabin at the stern of the ship. A red-coated marine stood guard at the entry to this illustrious compartment, where the captain hosted officers for formal dinners and conducted the vital business of running the ship. Next in line were the ship’s lieutenants, usually aspiring younger men but occasionally an older man who, though trained and experienced enough to be a commander, lacked the social standing or funds to purchase his advancement. They ate their meals and spent most of their leisure time in the wardroom, which was situated in the stern, directly under the quarterdeck. Marine officers were also present on warships, and although they had no role in sailing the ship they dined

with the other officers in the wardroom. One notch below the marine officers were the young gentlemen, or midshipmen, usually boys or young men who had not yet passed their exams for lieutenant.

SOCIAL HIERARCHY aboard Royal Navy ships was rigid and strict. A ship’s roster listed all hands, their positions and duties, and their pay. At the top, a virtual dictator with control literally over life and death, was the captain. He lived alone in a commodious private cabin at the stern of the ship. A red-coated marine stood guard at the entry to this illustrious compartment, where the captain hosted officers for formal dinners and conducted the vital business of running the ship. Next in line were the ship’s lieutenants, usually aspiring younger men but occasionally an older man who, though trained and experienced enough to be a commander, lacked the social standing or funds to purchase his advancement. They ate their meals and spent most of their leisure time in the wardroom, which was situated in the stern, directly under the quarterdeck. Marine officers were also present on warships, and although they had no role in sailing the ship they dined

with the other officers in the wardroom. One notch below the marine officers were the young gentlemen, or midshipmen, usually boys or young men who had not yet passed their exams for lieutenant.The list of non-commissioned warrant officers was extensive. These included the purser (responsible for provisioning both the crew’s food and the ship’s supplies, such as spare timbers for masts, rope for rigging, tar, coal, and timber planks), the gunner, the carpenter, the cook (usually a disabled pensioner who had no cooking skills whatsoever), and the master (who was responsible for navigation and directing the course of the ship, but never for making important decisions). Ships also were manned with what could be termed civilian officers, such as schoolmasters, chaplains, and surgeons; they also dined with the officers in the wardroom, but they did not have the authority to command. Marines were also part of the ship’s hierarchy, although their role was primarily to enforce the captain’s authority and to act as troops during combat. Lower still, only one notch above the common sailors, was the surgeon’s mate. The surgeon’s mate dwelt within the bowels of the ship, in a six-foot-square canvas enclosure in the cockpit on the orlop deck, directly above the hold in the front of the vessel, where the rocking was greatest, the air foulest, and the natural light faintest. It was barely large enough to contain a sea chest and a medical chest, and the canvas walls pinned to the overhead beams provided scant privacy from the general crew. The surgeon’s mate had no uniform, and though he was listed on the ship’s roster alongside warrant officers such as the gunner or the carpenter, he received less pay. Neither surgeons nor surgeon’s mates were highly regarded in the naval hierarchy, since the health of the crews was of little consideration and the benefits not entirely understood or appreciated.

It was as a surgeon’s mate that James Lind entered the Royal Navy in 1739. Although it was not a prestigious or well-compensated position, it was one of the best ways for a young medical professional without influential family connections to gain experience. Lind was

born the second child and first son of a well-to-do family of middle-class merchants in Edinburgh on October 4, 1716. He was well educated from a young age and perhaps took his interest in medicine from an uncle who was a physician. When he was fifteen years old he was apprenticed to a well-known Edinburgh physician and surgeon named George Langlands. By then he had acquired a solid foundation in Latin and Greek, the universal languages of learned professionals, particularly in medicine, and at least a reading knowledge of French and German. For eight years he learned the practical trade of a surgeon from Langlands, dressing and cleaning wounds, setting bones, mixing drugs, and letting blood. He studied the theoretical side of medicine under the handful of young physicians who had recently begun teaching at the University of Edinburgh.

These young and energetic physicians, who were appointed by the town council as “Professors in the University,” had all studied in Leiden, Holland, under the famous Dr. Hermann Boerhaave. They established the medical tradition at the University of Edinburgh and provided Lind with the theoretical and academic grounding that gave structure to his future studies. Langlands, coincidentally, was also a student of Boerhaave’s, as were most of the respected Edinburgh physicians at that time. Whether he agreed with them or not, Lind spent years learning Boerhaave’s theories on the humoral concept of disease, and they became the lens through which he viewed medical problems, including scurvy.

Although Lind began as a lowly surgeon’s apprentice, from an early age it was clear he had much grander ambitions. He studied languages and expressed an interest in medical theories, rather than concentrating purely on surgical work. In the eighteenth century there was a distinct separation between physicians, who concerned themselves with internal bodily functions and the theory of disease, and surgeons, who were concerned with fractures, cuts, and other physical injuries that could be helped by manipulation. Physicians were more educated and held a much higher social status than

surgeons. They earned more money and generally belonged to more respectable or richer families.

Lind’s surgical apprenticeship was more or less complete in 1739—the year Spain and England declared war and Anson began organizing his voyage. Rather than setting up a private practice in Edinburgh, difficult for a young, relatively inexperienced man, he applied to join the Royal Navy as a surgeon’s mate. A majority of surgeons in the Royal Navy at this time hailed from Scotland. Lind had no degree from his years of training, but this was not uncommon. He easily passed his examination at Surgeons’ Hall and was declared morally, physically, and professionally competent for the navy. For seven years he laboured as a lowly surgeon’s mate, learning the trade of a naval surgeon. “To the surgeon’s mate fell the most arduous duties and menial tasks,” wrote an early biographer of Lind’s named Edward Hudson. “He would boil the gruel, barley water, and fomentations, wash the towels and dressings, prepare and change dressings, mix and spread plasters, fill and carry the patients’ water buckets, sweep out the sick bay, and often be required to empty the buckets used as commodes. He was at the beck and call of the ship’s surgeon twenty-four hours a day.” It was also his duty to muster the sick each morning. A ship’s boy sauntered about the decks, ringing the sick bell and mustering the men for sick call, which was held in fine weather before the mast just below the quarterdeck. Anyone who was sick or injured presented himself to the surgeon and captain, justified and explained his injuries, and asked to be excused from his regular duties. The captain, in his impressive ceremonial uniform, with cocked hat athwart and sabre casually dangling (a uniform that cost as much as or more than the seaman’s annual salary), attended the muster to discourage sailors from faking illness and shirking duty (which was believed to be widespread in the navy but probably wasn’t, since sick mariners had their meagre pay docked and were sometimes charged for medications).

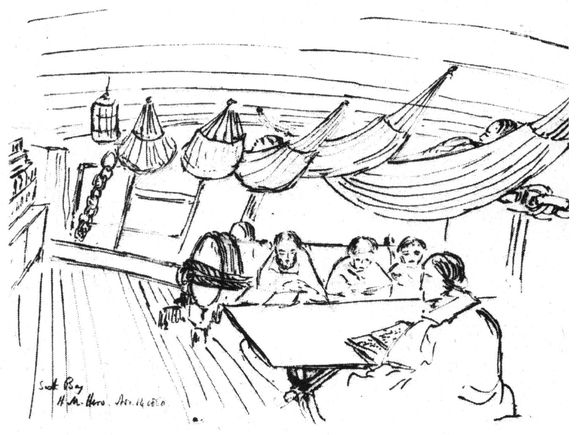

In the evening the surgeon’s mate made a round of the ship, inspecting the invalids in their quarters if they were officers or warrant officers and in the sick bay if they were common sailors. The sick bay was a damp, crowded, musty cell below the waterline where the fetid airs lingered and dim, smouldering lanterns provided the only light. The patients hung in hammocks suspended row upon row several deep with little over a foot of space between them. In it turbulent weather they might knock against each other. Sanitation was non-existent, and the patients, no matter their sickness or wounds, breathed the stale air and exhalations of their comrades, likely infecting each other and generally impeding any chance of quick recovery. In 1748 Tobias Smollett, who had entered the navy the same year as Lind, wrote Roderick Random, his classic tale of the life of a surgeon’s mate. It was a lurid and exaggerated account of the dreadful and morbid conditions aboard ships and the state of medicine. His description of the sick bay is a revealing, if overdone, account of what Lind himself would have been exposed to. “Here I saw fifty miserable distempered wretches, suspended in rows,” he wrote, “so huddled one upon another, that not more than fourteen inches space was allotted for each with his bed and bedding; and deprived of the light of day, as well as fresh air; each patient breathing nothing but a noisome atmosphere of the morbid steams exhaling from their own excrements and diseased bodies, devoured with vermin hatched in the filth that surrounded them, and destitute of every convenience necessary for people in that helpless condition.”

It must have been a startling and eye-opening initiation into the world for a twenty-three-year-old man from Edinburgh who had never been away from land before. Since Lind never wrote a memoir, we have no record of what he thought of this rude introduction to the harsh reality of life at sea—the foul food, stagnant water, harsh discipline, and, most important from a medical point of view, innumerable ailments from battle, fevers, and accidents. He dealt with the standard problems that are likely to arise in a group of several hundred close-quartered men of below-average health, pulling teeth, setting bones, issuing painkillers, treating venereal disease or the dreaded yellow fever, and calming those suffering from battle-induced dementia. He would have been able to saw off a mangled limb with good speed, quickly stitch up a gaping wound, realign a crushed leg bone, and, most important, know when a patient was beyond the help of his rudimentary medical abilities and call in the chaplain.

In the Age of Sail, the sick bay in a ship of the line was a damp, crowded, musty cell below the waterline in fetid air with dim smoldering lanterns providing the only light. Sanitation was non-existent, and the patients breathed the stale air and exhalations of their comrades, likely infecting each other and impeding any chance of quick recovery.

Naval records show that Lind participated in at least one battle, the attack on the Spanish island of Minorca in 1739, and he likely experienced many other instances where storms, minor skirmishes, serious shipboard accidents, or infectious diseases laid low significant portions of the crew. During battle he would have joined the surgeon in the cockpit or sick bay, awaiting the wounded. As a surgeon’s mate he would have readied the battle dressing station, ensuring it was well stocked and supplied, and assisted the surgeon in any capacity required. The dressing station contained “water, lint, dressings, sponges, tourniquets, buckets of sand to absorb blood, tables for operating, and for instruments, a chest of drugs, and blankets on which to lay the wounded.” After several years of merely assisting, he might have actually completed his own surgeries. Following a battle, the cockpit was like a slaughterhouse. Screeching men—some with mangled or severed limbs, others with great oak splinters protruding from them, and still others with hideous burns—were brought down into the gloom, many never to return to the world above. Blood spattered over everything as the surgeons gouged into flesh to remove splinters and sawed and cut through bone and muscle. Wounds were cauterized with boiling tar.

The survival rate for serious injuries was very low, sterilization and anaesthetics other than rum non-existent, and surgical techniques in their infancy. It must have taken a philosophical and

practical mind to have thrived under such conditions. But thrive Lind must have, for not only was he promoted to ship’s surgeon but he eventually rose to become a prominent Edinburgh physician and then head of England’s largest and newest hospital. During his long years in the Royal Navy, on voyages to the West Indies, the Mediterranean, and western Africa, Lind learned the surgeon’s job well and spent considerable time observing shipboard conditions, undoubtedly laying the foundation for all his later studies and writings on naval hygiene and sea diseases. He synthesized a great deal of information during his tenure at sea. Many of his later essays and books are cogent and useful; they show a clear mind and a desire to understand the root of problems instead of being intoxicated by the heady vapours of theory so prevalent at that time. In his lowly capacity as surgeon’s mate, it is unlikely he ever made his opinions known—except perhaps in his own journal, which he was under a professional obligation to keep and which would have been carefully scrutinized by the medical examining board before he was promoted. Lind was a physician at heart, intrigued much more by the peculiar puzzle of understanding the causes of and cures for disease than by the mere treatment of physical wounds.

In late 1746, Lind turned in his medical and surgical journals and passed his examinations for surgeon. He was promoted aboard HMS Salisbury, for a round of duty in the English Channel and the Mediterranean. The Salisbury was a fourth-rate ship—that is to say, it was the smallest of ships considered ships of the line, or battleships, and just larger than the fifth or sixth rates, which were considered frigates. While the largest ships boasted more than one hundred great guns, with a displacement of 2,000 to 2,600 tons and capable of holding 850 to 1,000 sailors, the fourth-rate Salisbury had 50 to 60 great guns, was about 1,100 tons, and held about 350 mariners. It might have been only 150 feet long, making for very cramped living conditions and little privacy. Although it was not the largest ship Lind had served aboard, it was still a huge vessel,

and because of its size it afforded an array of sick sailors, including a large contingent of scorbutic patients who began to show symptoms several months into the tour of duty.

As ship’s surgeon, Lind, now thirty-one years old and competent by naval standards, dreamt up a remarkable scheme that reveals a great deal about his analytical and practical mind. Scurvy was no stranger to Lind after eight years in the navy, and as surgeon he would have been directly responsible for ministering to mariners down with the affliction. Scurvy probably reared up in every ship he served on, though there is no record of whether he himself suffered from it. Lind would have been familiar with all the common “cures,” and aware also that they seldom had any beneficial effect. Accordingly, showing an astonishing propensity for originality, for thinking outside the strict lines of contemporary thought, he planned an experiment to test and evaluate the effectiveness of the most common antiscorbutics. He was fortunate that his captain, the Honourable George Edgecombe, was a fellow of the Royal Society whose scientific interests meshed with his own. Lind could not have conducted his experiment without the complicity, or at least the blessing, of his captain. Many naval captains would not have been so open to new ideas, and most never would have permitted Lind the time and resources to conduct his experiment.

During April and May of 1747, the HMS Salisbury cruised the English Channel with the other ships of the Channel fleet. Though the ship was never far from land, scurvy began its insidious appearance. More than four hundred of the fleet’s four thousand mariners were showing symptoms, and most of the regular crew of the Salisbury were affected to some extent, with nearly eighty seriously weakened. On May 20, Lind, with the agreement of his enlightened captain, though not necessarily with the consent of the scorbutic sailors, took aside twelve men with advanced symptoms of scurvy “as similar as I could have them.” They “all in general had putrid gums, the spots and lassitude, with weakness of their knees.”

Lind hung their hammocks in a separate compartment in the fore-hold—as dank, dark, and cloying as can be imagined—and provided “one diet common to all.” Breakfast consisted of gruel sweetened with sugar. Lunch (or dinner) was either “fresh mutton broth” or occasionally “puddings, boiled biscuit with sugar.” And for supper he had the cook prepare barley and raisins, rice and currants, sago and wine. Lind also controlled the quantities of food eaten. During the fourteen-day period, he separated the scorbutic sailors into six pairs and supplemented the diet of each pair with various antiscorbutic medicines and foods.

The first pair were ordered a quart of “cyder” (slightly alcoholic) per day. The second pair were administered twenty-five “guts” (drops) of elixir of vitriol three times daily on an empty stomach and also “using a gargle strongly acidulated with it for their mouths.” A third pair took two spoonfuls of vinegar three times daily, also on an empty stomach, also gargling with it and having their food liberally doused with it. The fourth pair, who were the two most severely suffering patients, “with the tendons in the ham rigid,” were given the seemingly oddest treatment: sea water, of which they drank “half a pint every day, and sometimes more or less as it operated, by way of a general physic.” The fifth set of sailors each were fed two oranges and one lemon daily for six days, when the ship’s meagre supply ran out. The sixth pair were ordered an “electuary” (medicinal paste), “the bigness of a nutmeg,” thrice daily. The paste consisted of garlic, mustard seed, dried radish root, balsam of Peru, and gum myrrh. It was washed down with barley water “well acidulated with tamarinds.” And on several occasions they were fed cream of tartar, a mild laxative, “by which they were gently purged three or four times during the course.” Lind also kept several scorbutic sailors aside in a different room and gave them nothing beyond the standard naval diet other than the occasional “lenitive electuary” (painkiller) and cream of tartar.

This experiment was one of the first controlled trials in medical history, or in any branch of clinical science. The results were surprising. The lucky pair who were fed the oranges and lemons (which, according to Lind, they “ate greedily”) were nearly completely recovered by the time the fruit supply dwindled after only a week. One of the men responded to the treatment so remarkably that although the “spots were not indeed at that time quite off his body, nor his gums sound,” he returned to duty after a gargle of elixir (oil) of vitriol. He was followed soon thereafter by his companion, and both were then “appointed nurse to the rest of the sick” for the remainder of the trial.

Those who had drunk the cider also responded favourably, but at the end of two weeks they were still too weak to return to duty. Still, they showed slight improvement, such that “the putrefaction of their gums, but especially their lassitude and weakness, were somewhat abated.” On an earlier voyage Lind had observed that cider did not fend off the advances of scurvy but seemed to slow its progress. A great number of sailors lingered long in sickness but did not perish as quickly as those who were not drinking cider, or who were drinking beer or rum punch instead. Modern researchers have shown that cider, particularly if not overly purified, pasteurized, or stored for too long, does contain small quantities of ascorbic acid, and therefore could have been a mild preventative. The unfortunate men who gargled and drank the elixir of vitriol found their mouths “much cleaner and in better condition than the rest,” but Lind “perceived otherwise no good effects from its internal use upon the other symptoms.” He also observed no positive effects from the vinegar, the sea water, or the electuary-and-tamarind concoction. His conclusion was that “the most sudden and visible good effects were perceived from the use of the oranges and lemons … . Oranges and lemons were the most effectual remedies for this distemper at sea.”

Most unusual was Lind’s decision to give sea water to the two worst cases in his trial. He suspecred, or hoped, that the easily obtainable sea water would prove to be beneficial—certainly this would have been excellent news to the Admiralty, as it was both cheap and of infinite supply. Lind later wrote of hearing tales of “numberless instances of giving salt water in very bad scurvies … with great benefit.” Sea water was still pronounced a viable and effective scurvy cure years later—in published accounts by professional physicians. In Lind’s official trial, however, he found that it had no effect whatsoever—not surprising, from a modern viewpoint, but perhaps disappointing to Lind. Elixir of vitriol was the most commonly issued antiscorbutic medicine used by the Royal Navy at the time, so for Lind also to have proven it entirely ineffective was a small advancement in itself, although it took six years of work before he published any of his findings, and even then, in spite of his seemingly clear proof, not everyone agreed with his conclusions.

In 1748, hostilities between England and Spain abated and Lind retired from the Royal Navy, on half pay for a number of years. He returned to Edinburgh, where he set out to complete his medical degree, producing a hastily researched and written thesis on venereal lesions titled De morbis venereis localibus, which proved adequate to satisfy the requirements. That same year he became “a Graduate Doctor of Medicine in the University of Edinburgh.” With a licence from the Royal College of Physicians to practise “within the City of Edinburgh & Liberty ye of without any trial or Examination,” he began to offer his services to the city and surrounding region on May 3, 1748. In his quiet, unpretentious manner, he thrived by virtue of good work and a dedication to his profession.

In 1750, Lind was elected a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. His private practice was thriving. He was a private man with little interest in attracting public attention, and very little is known of his personal life, other than that he was

extremely dedicated and hard-working, often continuing his scurvy research in the evenings after he left his office. Judging by the competence he later showed as a hospital administrator, and the thoroughness of his essays and books, we can conclude that he was a conscientious and responsible physician, willing to admit when an illness eluded his understanding—not necessarily the norm for the time. It was during his tenure in Edinburgh that he married awoman named Isobel Dickie. Little is known about her other than that she died two years after Lind, on March 6, 1796, at the age seventy-six—so she was in her late twenties or early thirties when they wed and would have likely come from a well-established middle-class family. The couple had one son, named John, who also became a surgeon and a physician.

After several years of working towards professional respectability and financial stability, Lind began to write an essay about his Salisbury trial and his observations on scurvy. When the voluminous information began to overwhelm him, he decided to turn his essay into a comprehensive book. He spent years collecting every known description of scurvy, from ancient times to the most recent, writing hundreds of letters to foreign colleagues, acquiring documents from around Europe and either translating them himself or having copies translated for him. The work contained a great bibliotheca scorbutica, a collection and review of every medical opinion and account of the disease that Lind could unearth. This in itself was no small task for a working doctor to do in his spare time, without reliable mail service and modern telecommunications tools. “What was intended,” he wrote, “as a short paper to be published in the memoirs of our medical naval society … swelled to a volume.”

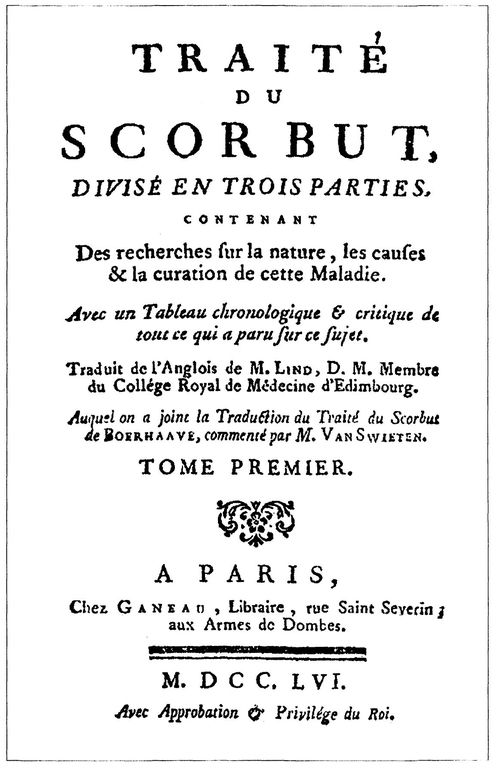

It was not until 1753 that Lind’s Treatise on the Scurvy, Containing an Inquiry into the Nature, Causes, and Cure, of That Disease Together with a Critical and Chronological View of What Has Been Published on the Subject appeared in Edinburgh. Other editions in other countries and languages soon followed. Six years had passed since he had

conducted his controlled trial aboard the Salisbury, but the incidence of scurvy in the Royal Navy had not changed in the slightest during the intervening years. Lind dedicated his work to “The Rt. Hon. George, Lord Anson,” who was at that time, a decade after his historic cruise in pursuit of the Manila galleon in the Pacific, the influential First Lord of the Admiralty. The published account of Anson’s voyage was released in 1748, the year Lind left the Royal Navy, and there is little doubt that Lind read the account, and that it stimulated his further inquiry into scurvy while he was in Edinburgh. Lind wrote in the preface to the first edition of his treatise that “after the publication of the Right Honourable Lord Anson’s voyage, by the Reverend Mr. Walter, the lively and elegant picture there exhibited of the distress occasioned by this disease, which afflicted the crews of that noble, brave, and experienced Commander … excited the curiosity of many to inquire into the nature of a malady accompanied with such extraordinary appearances.” He was aware of the terrible toll scurvy took on Anson’s crew, and it was one of the main reasons he began anew his studies into the dreaded disease.

The treatise was a four-hundred-page tome that, in addition to presenting a comprehensive list and analysis of current and historical theories and cures for scurvy, outlined Lind’s strong personal opinions on the benefits of a cure not only for individual sailors but for the Royal Navy and England in general. In case others had not yet grasped the significance, Lind spent considerable time making his case before launching into his assessment of the disease’s causes, prevention, and cure. Lind made his plea: “Common humanity ever pleads for the Afflicted … . But, surely, there are no lives more valuable to the State, or who have a better claim to its care, than those of the British sailors to whom the Nation, in great measure owes its Riches, Protection, and Liberties.”

Lind also wrote in his preface that “the scurvy alone, during the last war, proved a more destructive enemy, and cut off more valuable lives, than the united efforts of the French and Spanish arms.” The statistics on the incidence of scurvy in the Royal Navy during the Seven Years’ War a decade later, when more accurate records were kept, corroborate Lind’s claim. In hindsight, it seems preposterous that a sickness that was the acknowledged cause of such devastating loss of life and such a drain on naval power could be allowed to go so long without government intervention, but in the mid-eighteenth century the benefits of a healthy crew were not entirely appreciated by those in command, and prevention was considered a foolish waste of resources and time. Lind was clearly interested in preventative, rather than curative, medicine—if the distemper could be prevented, he reasoned, it need not be cured. But in this he was far ahead of his time. Ignorance of medical matters was rife in the officers’ ranks, as medical approaches and concerns were not part of their training.

The title page of an early French edition of Lind’s Treatise on the Scurvy, showing the influence of Hermann Roerhaave in mid 18th century medical circles.

Lind explained in his treatise that even when scurvy didn’t directly claim the lives of crew members, it weakened them, hindering their ability to do their duty with vigour and withstand other diseases. Scurvy, he wrote, “has not only occasionally committed surprising ravages in ships and fleets, but almost always affects the constitution of sailors; and where it does not rise to any visible calamity, yet it often makes a powerful addition to the malignity of other diseases.” It was a perceptive and accurate observation based on his years at sea. After outlining the benefits of finding a cure, Lind described in detail the particulars of his clinical trial aboard the Salisbury (including his conclusion that oranges and lemons were the best cures), and then listed his other suggestions for staving off the affliction and offered his theory of the disease.

Lind’s detailed analysis of the explanations for scurvy found in ancient and more recent works was unusually cogent, and reading it would have given any physician a solid understanding of what was then known of the disease. It is a literature review of the period up to 1753. “Before this subject could be set in a clear and proper light,”

he claimed, perhaps as a justification for the years he spent collecting and reviewing every description of scurvy he could find, “it was necessary to remove a great deal of rubbish.” Much of what had been proposed by medical thinkers up to that point, and regrettably beyond, was indeed rubbish, and it could not possibly have been based on anything other than personal opinion or fashion.

Lind apologized to the many “eminent and learned authors” whose work he criticized, claiming that it was done not with “a malignant view of deprecating their labours, but from regard to truth and to the good of mankind.” For one prominent seventeenth-century Dutch writer, Severinus Euglenus, who attributed a great many ailments to the “scorbutic taint,” Lind reserved particular ire, claiming that “his vanity and presumption are indeed intolerable.” The disease was caused, according to Euglenus, by “divine permission, as chastisement for the sins of the world.” Certain men, Lind caustically observed, continued to follow Euglenus’s lead, and “they even exceed him in absurdities.”

Lind’s criticism of the many preposterous theories was a refreshing departure from the stultifying uniformity of medical thought at the time, and his insistence on having evidence and proof before accepting the validity of a theory ought to have been common practice. From a modern perspective, one wonders how it couldn’t have been. His clinical trial, although crude and rudimentary by modern standards, was a true advancement. There are examples of a handful of clinical trials dating from as early as the eleventh century, but somehow the concept never took hold. So it is all the more saddening and curious that, after providing a balanced and thorough critique of the medical theories on scurvy, a concise diagnosis of its symptoms and progression, and accurate and effective suggestions for cures, Lind then becomes derailed with a verbose and gaseous theoretical pronouncement on scurvy’s cause.

His complicated and peculiar theory is difficult to correlate even with his own observations. Perhaps Lind’s greatest failing was that

he didn’t turn his own critical analysis, so effectively deployed to demolish the erroneous presumptions of other physicians, on himself. Lind’s theory of the cause of scurvy is as preposterous and harebrained as any of the theories he so eloquently criticized. It seems to have been pulled from the air. Although it is difficult to coherently summarize, his convoluted and ornate argument is basically that scurvy is caused by blockage of the body’s natural perspiration, which leads to an imbalance in the body’s alkalinity. This unfortunate imbalance, he claimed, is caused by the dampness at sea and aboard ships. Although Lind had proven by trial and error that fresh greens and citrus fruits were the most effective antiscorbutics, his analysis of the root causes of scurvy was, unfortunately, an elaborate and foolish guess. It is easy to see Boerhaave’s influence on his theory of disease, though Lind mercifully put no stock in the malignant properties of foul vapours and he never referred to the spleen.

“An animal body,” Lind begins, “is composed of solid and fluid parts; and these consist of such various and heterogeneous principles, as render it, of all substances, the most liable to corruption and putrefaction … . For by the uninterrupted circulation of its fluids, their violent attrition, and mutual actions on each other, and their containing vessels, the whole mass of humours is apt to degenerate from its sweet, mild, and healthful condition, into various degrees of acrimony and corruption … . The most considerable of all the evacuations, is that by insensible perspiration; which Sanctorius found in Italy to be equal to five eighths of the meat and drink taken into the body … . And it is certain these excrementitious humours naturally destined for this evacuation, when retained long in the body, are capable of acquiring the most poisonous and noxious qualities … becoming extremely acrid and corrosive: and do then give rise to various diseases.”

It another physician had produced such a theory, Lind would likely have dissected it and dismissed it as “a great deal of rubbish.” But he probably felt that he needed an important-sounding theory

in order to be taken seriously in the medical community, which at this time conducted discourse in complicated, imprecise language. Perhaps Lind even believed this argument—though it runs counter to his rigorous observations and analysis of the work of others. Under his theory, all acids would have been scurvy cures, yet his own trial showed conclusively that vitriol and vinegar had no effect whatsoever on scorbutic patients. Oddly, Lind even acknowledged the flaws in his own reasoning. “For some might naturally conclude,” he admits, “that oranges and lemons are but so many acids, for which, vinegar, vitriol, etc. would prove excellent substitutes. But, upon bringing this to the test of experience, we find the contrary. Few ships have ever been in want of vinegar, and, for many years were supplied with vitriol. Yet the Channel fleet often had a thousand men miserably over-run with this disease … . Although acids agree in certain properties, yet they differ widely in others, and especially in their effects upon the human body.” Lind was confused, and as he attempted to patch up each new unravelling thread in the fabric of his theory, it became more and more difficult to reconcile with common sense. After acknowledging that, theoretical similarities aside, certain acids had a special “other property,” he failed to show what this other property was.

Lind’s greatest failure was his attempt to conform to the prevailing intellectual model for the theory of disease. To be respected by his medical peers, he had to explain scurvy and show how it fit within the greater framework of disease in general—to devise a theory that would apply not only in specific cases but could be the foundation for an understanding of all ailments of the human body. With such a lofty objective for medicine at the time, it is no wonder Lind failed to squeeze every symptom and observation into a grand synthesis of all sickness. He fell prey to the same tendency to theorize that he dismissed in others, and yet he seems to have been aware of his own failings. “Of theory in physic,” he admits, “the same may perhaps be said, as has been observed by some of zeal in religion,

that it is indeed absolutely necessary yet, by carrying it too far, it may be doubted whether it has done more good or hurt in the world.” While Lind came upon the cure for the disease, he was simply incapable, because of a lack of resources, knowledge, and the insight of other scientists, of deriving the cause. Taking his study further was beyond his capacity at that time.

For various reasons, not the least of which might have been Lind’s own convoluted theories of the causes of scurvy and his inability to explain why orange and lemon juice should cure the sickness, his recommendation for citrus juice as a preventative and his assertion that oil of vitriol had no antiscorbutic properties were not heeded. His practical cure was lost in the cloud of theories, including his own. Within a few years of the publication of Lind’s treatise, several other physicians produced essays that directly contradicted his suggestions, even for a cure. The lack of enthusiasm for Lind’s ideas within the medical community, which was caused by his own impolitic, though honest, criticisms of his peers, might also have delayed the acceptance of his conclusions. Lind didn’t shy from criticizing his contemporaries. Two men in particular did not appreciate his trampling on their turf.

In the same year that Lind’s treatise was published, a well-known and influential physician named Anthony Addington, a man who walked in high circles, as personal physician to William Pitt, the prime minister, and was well acquainted with several lords of the Admiralty from his Oxford days, published An Essay on the Sea Scurvy: Wherein Is Proposed an Easy Method of Curing That Distemper at Sea, and of Preserving Water Sweet for Any Cruize or Voyage. He dedicated his book to all seven lords of the Admiralty by name. It was an unusual tome from a man whose specialty was in mental disorders, and who had never gone to sea. His description and

analysis of scurvy was based on the very accounts Lind had criticized. Compared with Lind’s clear analysis of the symptoms and progression of the disease, Addington’s seems unlikely to have been published contemporaneously. “In the last stage,” Addington writes, “which is contagious, [scurvy] produces horrors of imagination; trembling, panting, convulsive, epileptic fits; weakness of memory and reason, lethargies, palsies, apoplexies; purple, livid and black spots; violent effusion of blood from every internal and external part of the body; putrid fevers, hectic, continued and intermittent: exquisite rheumatic pains, pleurisies, the jaundice, obstinate costiveness, colics, vomiting, diarrheas, dysenteries, mortifications.” One wonders, in Addington’s world, what symptoms were not the result of scurvy. Nevertheless, the influential doctor pronounced with authority that the best scurvy cures were sea water—both for drinking and for purging—and bloodletting, to reduce the hemorrhaging. To preserve sea water and prevent it from going putrid, and thereby contributing to scurvy, he proposed adding hydrochloric acid to a small quantity and then blending it with the ship’s drinking water.

Lind’s treatise was published only a few months after Addington’s essay, and Lind was not overly kind in his assessment of Addington’s analysis, dismissing it as valueless and ill-founded, which it was. A. P. Meiklejohn wrote in 1951, in the Journal of the History of Medicine, that “though there is no record of his [Addington’s] opinion of Lind, it was unlikely to have been favourable and somewhere, at some time, this might well have told against Lind.”

Lind also had a sour relationship with Charles Bisset, a peer and acquaintance from his days as a student in Edinburgh. Unlike Addington, Bisset had considerable experience at sea and in treating naval disorders. In 1755 he released A Treatise on the Scurvy, Designed Chiefly for the Use of the Brutish Navy, a tract influenced by Lind’s treatise and designed to counter what he considered Lind’s erroneous position. Bisset proposed that scurvy could take one of several

distinct manifestations, including “Malignant, Continued, Remitting and Intermitting Fevers and Fluxes” and scorbutic ulcers. He claimed as scorbutic many symptoms that clearly were not scurvy. The core of Bisset’s belief was that solar heat weakens the “vital powers,” and that they become “unequal to the density and tenacity of the gross navy-victuals: the animal juices which they prepare from this ailment are therefore crude, viscid, light and unequally mixed: the bile, and other chylopoietic juices become too oily, and much depraved: the ingested rancid oil of meat that is tainted retains its nature, and contributed with reassumed and acrid animal oil, to increase the unequal and preternatural mixture, and depravity of the circulating juices.”

It would be a painful task to try to clearly summarize the entirety of Bisset’s ponderous and pedantic argument, much of which appears designed to impress the reader with his use of uncommon, learned words. But on one point he is unmistakably clear: James Lind is not to be credited with understanding scurvy. “Dr. Lind reckons the want of fresh vegetables and greens a very powerful cause of the scurvy,” he writes condescendingly. “He might, with equal reason, have added fresh animal food, wine, punch, spruce beer, or whatever else is capable of preventing this disease.” Bisset, not surprisingly, had his own recommendation for the greatest antiscorbutic: rum or other suitable hard liquor, diluted with water and laced with sugar. Sugar “renders more aperient, detersive, and less heating, and highly antiscorbutic: for sugar, notwithstanding the groundless prejudice which many entertain against it, is aperient, detersive, demulcent, antiseptic, and consequently an excellent medicine against the scurvy.” Bisset also believed that rice has “very powerful antiscorbutic and restorative qualities.” Lind never responded to Bisset’s treatise.

Bisset’s antipathy to Lind might have arisen out of a difference in political leanings. While Bisset served in the army on the Hanoverian side to repel Charles Edward Stuart’s rebellion in Scotland in

1745) Lind was likely a closet Jacobite. Although Lind never took part in any battles of the Jacobite rebellion, or left any record of his sympathies, A. P. Meiklejohn observed that “when the time came to have his portrait painted it was done, not by one of the great portrait artists of the day, but by a dispossessed Scottish Jacobite, Sir George Chalmers.” Bisset also had influential friends within the scientific and medical community, not the least of whom was the aristocratic Scottish physician Dr. (later Sir) John Pringle.

Pringle was at various times throughout his career the surgeon general of the English army, physician to King George III, and author of the groundbreaking book Observations on the Diseases of the Army, in which he emphasized sanitation and hygiene to improve the health of soldiers. Pringle also pioneered the concept that hospitals should be respected as sanctuaries by both sides during war. His clients included nobility and the influential lords of the realm. Even before he became president of the Royal Society in 1772, he was a man with clout, social stature, and influence. Pringle took a great interest in James Cook’s voyages and in scurvy throughout the 1770s, and he had considerable influence on the Admiralty’s choice of antiscorbutics during the era of the War of American Independence.

Men like Addington and Bisset were respected and influential, more so than Lind, and it is not surprising that in that day and age, when connections and social standing frequently counted for more than competence, their claims, pronounced without a shred of verifiable evidence, were given the same consideration as Lind’s. But Lind’s remarkable trial aboard the HMS Salisbury at least set a foot on the path to finally understanding scurvy—the evidence of his trial was published and available for others to read.

Before Lind’s experiments, scurvy was not clearly defined as a disease. The term was used as a catchphrase to include all manner of

nautical ailments. The seventeenth-century naval surgeon John Hall wrote in The Power of Water Dock against Scurvy that “if anyone is ill, and knows not his Disease, Let him suspect the scurvy.” Nevertheless, for years after Lind’s treatise was published, scurvy remained as much a problem as ever. But slowly the Admiralty began to take a greater interest in solving the scurvy problem. The growing body of information that painted scurvy, “this foul and fatal mischief,” as the greatest of all obstacles to the navy’s objectives was becoming too large to ignore, and the implications of not solving the problem were becoming increasingly significant.

Unfortunately, it was more than the preposterous foundations of medical reasoning that hampered the study of the disease. Lind had difficulty determining the exact cause of scurvy in part because mariners suffered from so many other diseases and dietary deficiencies that isolating the symptoms of one condition was a complex and bewildering task. But the officers and young gentlemen aboard ships suffered far less from scurvy than the general crew, and Lind speculated that this was at least partly because of their better overall health and diet.

While Lind recognized that the lack of fresh provisions was directly linked to scurvy, he also advocated warmth, proper rest, and proper ventilation in ships—all things that would no doubt have benefited the average sailor, reducing the body’s rate of consumption of ascorbic acid. But they would have been insufficient to cure or prevent scurvy on prolonged voyages. Lind knew instinctively that conditions inherent to a life at sea during the Age of Sail, such as cold, damp, infection, alcohol, discontent, and stress, directly contributed to scurvy. “As the atmosphere at sea may always be supposed to be moister than that of the land,” he wrote, “hence there is always a greater disposition to the scorbutic diathesis at sea than in a pure dry land air.” Life at sea was harsh and cruel and lonely, and Lind was very perceptive when he observed that it strengthened the clutches of scurvy.

In 1757. Lind. continuing his work on naval hygiene and disease and revealing his sympathy for the plight of the average seaman and the atrocious conditions in the Royal Navy, wrote a second book, called An Essay on the Most Effectual Means of Preserving the Health of Seamen in the Royal Navy. In this essay, Lind defined what he believed to be the responsibility of a naval surgeon, and he outlined his suggestions for ameliorating the harsh and foul conditions for common sailors aboard ships. He further developed his view that preventing disease was far more advantageous than curing it, and that cleanliness and better conditions for mariners would not only reduce the incidence of scurvy but aid in limiting other diseases as well. “The Prophylactic or preventative branch of medical science does,” Lind wrote, “in many instances, admit of as much, or even more certainty, than the curative part … . A medicine, which effectually prevents, deserves to be more esteemed than that which merely removes … . With regard to the Royal Navy, when men are preserved in health by proper management; Courage and Activity are the certain consequences.”

Perhaps most significantly, Lind argued for the quarantine of newly impressed sailors and convicts released from prison to prevent the new recruits from bringing infectious fevers into the crowded ships. He also accurately pointed out that the practice of loading a ship with double the number of mariners needed to sail it was a major cause of high mortality rates from disease. Crowded ships and poor hygiene fed on one another. Without good hygiene and proper food, Lind wrote, the navy would continue to need the extra men because they would continue to die at alarming rates. He was the first medical writer to point this out. Lind’s essay was a remarkably enlightened social document for the time, so it is unfortunate that most of his recommendations were ignored for many years.

Although Lind never returned to sea, he had an opportunity, perhaps unequalled by any other physician in Europe, to study

scorbutic patients and other naval diseases. In 1758, he was appointed chief physician to the Royal Naval Hospital at Haslar, the largest and newest hospital in the country.