BLOCKADE: THE DEFEAT OF SCURVY AND NAPOLEON

ON THE CLEAR, GUSTY MORNING of October 21, 1805, twenty-seven British ships of the line—massive floating castles with hundreds of mariners, red-coated marines, and as many as one hundred blackened iron twenty-four- and thirty-two-pounders protruding from the gun ports—closed on an equally impressive French and Spanish fleet of thirty-three warships that hastily assembled into a ragged battle line off Cape Trafalgar, near Cadiz on the south coast of Spain. Admiral Pierre Villeneuve commanded the combined French and Spanish fleet, while the celebrated Horatio Nelson commanded the British fleet. Nelson ordered his signals midshipman to raise on the halyard a final communication to the well-trained commanders of his ships. The anxious midshipman raised the series of coloured flags on the quarterdeck of the Victory and spelled out the message “England Expects That Every Man Will Do His Duty.”

ON THE CLEAR, GUSTY MORNING of October 21, 1805, twenty-seven British ships of the line—massive floating castles with hundreds of mariners, red-coated marines, and as many as one hundred blackened iron twenty-four- and thirty-two-pounders protruding from the gun ports—closed on an equally impressive French and Spanish fleet of thirty-three warships that hastily assembled into a ragged battle line off Cape Trafalgar, near Cadiz on the south coast of Spain. Admiral Pierre Villeneuve commanded the combined French and Spanish fleet, while the celebrated Horatio Nelson commanded the British fleet. Nelson ordered his signals midshipman to raise on the halyard a final communication to the well-trained commanders of his ships. The anxious midshipman raised the series of coloured flags on the quarterdeck of the Victory and spelled out the message “England Expects That Every Man Will Do His Duty.”A good number of the British sailors, hardy tars who had known war with France for more than a decade, had seen battle before, and

they knew what lay ahead—multi-layered oak hulls burst asunder by spiralling iron balls; ships’ decks raked with grapeshot; great guns overheating and shattering, exploding near the gunners; bodies and limbs pulverized by shot and pierced by wooden shrapnel from splintering walls and masts; a horror of chaos and carnage, followed by the whimpering moans of the wounded. As the fleets drew near, the decks were sanded rough to prevent sailors from slipping in the anticipated slush of blood and gore, the bulkheads and walls of the officers’ quarters were cleared for action, splinter netting was hung to prevent fighting men from being crushed by falling debris, and sharpshooters nestled into the rigging of each ship.

Nelson had divided his force into two squadrons. The Victory and the equally large first-rate Royal Sovereign led their warships towards Villeneuve’s battle line at a ninety-degree angle in an attempt to break through and attack from both sides and isolate the French vanguard from the battle. It was a strategy that ran counter to the accepted and formalized rules of naval warfare (which held that the two lines should be parallel and sail past each other with guns ablaze), but it had proved brutally effective twenty-three years earlier at the Battle of the Saints and during Nelson’s other celebrated engagements with the French at the Battle of the Nile and the Battle of Cape St. Vincent. Although the lead ships would have to withstand five or six broadsides before returning fire, when they did unleash their first broadside it would rake through the stern of the enemy ship. Nelson was counting on superior British gunnery and sailing expertise once they had broken the battle line.

The first broadsides were fired at the Royal Sovereign as she ploughed through the French battle formation. Firing a raking shot into the stern of the Santa Anna in return, the Royal Sovereign delivered a devastating blast that killed or wounded four hundred mariners and dismounted twenty great guns. Thirty men were wounded and fifty dead on the Victory, meanwhile, and terrible damage was inflicted to the prow of the ship before she too ploughed through the French line and fired her first broadside into the stern of the Bucentaure.

After the British ships shattered the French line, the battle degenerated into a furious melee between individual ships amidst clouds of acrid smoke, deafening cannon roar, and screaming men. Stripped to the waist in the sauna-like interior of the gun decks, with dirty bandanas wrapped around their heads to shield their ears, gunners raced to reload smoking hot cannons, cringing each time the blast shook the foundation of their wooden world and lobbed hundreds of pounds of iron shot in a fiery blast. Cutlass-swinging warriors flung themselves across the distance between ships, crawling through gun ports, scrambling over the gunwales, or clinging to dangling rigging and broken masts to engage the enemy hand to hand and take ships by force.

After nearly five hours of relentless battle, hulks of ships lay mashed, lurching aside with water flooding in through gaping holes. Masts and rigging were a tangled, crumpled mess; corpses were strewn about the blood-soaked decks. In the dark and swirling water, bodies bobbed between the wreckage and debris of the once majestic ships. One huge vessel burned uncontrollably, flames flickering in the evening sky and sending coiling plumes of oily black smoke upward. The moaning of dying and maimed men was a terrible dirge.

The events leading to this momentous battle had been set in motion months earlier by the diminutive Corsican general and tactical genius Napoleon Bonaparte. It was his attempt to end the stalemate at sea that had endured since England and revolutionary France went to war in 1793. Britain, in a shifting series of Continental alliances, had been at war constantly throughout this time (apart from a brief period of official peace between March 1802 and May 1803), and it

would remain at war until Napoleon’s defeat by a combined British and Continental army at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Napoleon rose to prominence in the revolutionary government of France after brilliant military victories in the 1790s. He was a virtual dictator by 1799. He finally dispensed with the egalitarian ideals of the revolution altogether and crowned himself emperor in 1804. Ruthless and ambitious, he wanted nothing less than total European dominion, an accomplishment that remained elusive as long as Britain was free and supporting dissent through financial subsidies, with military supplies, and occasionally with troops. “Let us concentrate our efforts on building up our fleet and destroying England,” Napoleon proclaimed in 1797. “Once that is done Europe is at our feet.”

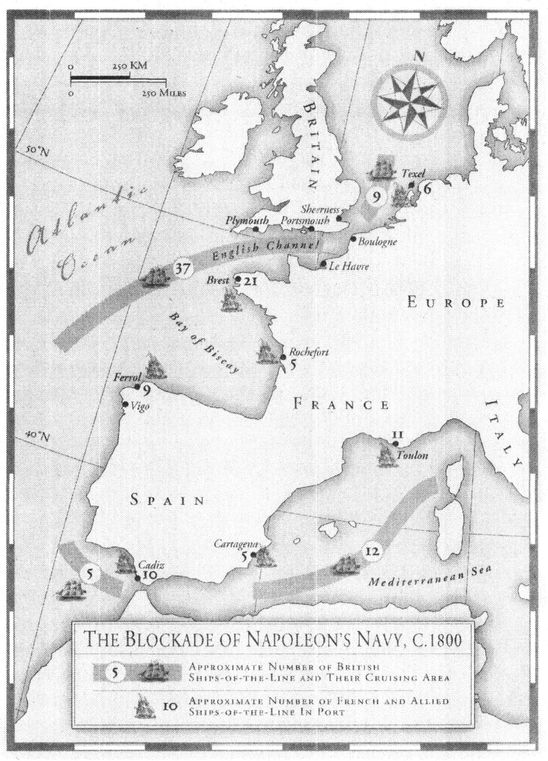

On land Napoleon was nearly invincible, but at sea British fleets controlled the trade routes and maintained a year-round watch on French ports. Although Napoleon had 130,000 troops in two thousand flat-bottomed invasion barges massed along the northern coast of France, he had been unable to transport them across the Channel because of the constant vigilance of and threat posed by the superior force of the Channel fleet. The Channel was only a few miles wide, and in good weather even unseaworthy barges could safely cross in a single day—assuming they had control of the Channel to protect them as they made the crossing. The French army was superior in numbers to British land forces, and vastly more experienced. Had troops landed in England, their victory would almost have been assured. The vast bulk of the French navy, however, and the ships of her Spanish allies were sheltered in ports ringing western Europe, from Texel in the English Channel to Toulon in the Mediterranean. The Continental blockade was intended not to prevent all ships from entering and leaving French and Spanish ports, or to destroy or harry Continental commerce (both Britain and France authorized thousands of independent privateers to prey on enemy commercial shipping), but to contain Napoleon’s warships in port

in small fleets and never to allow them to congregate into a single force without first having to contend with a British fleet of superior force. Although employed successfully in a limited capacity in the Seven Years’ War half a century earlier, the blockade was a calculated gamble, and despite some early success in the late 1790s no one knew until 1805 whether it could repel an organized and concerted invasion effort.

The blockade had wearily dragged on for ten years before Trafalgar and would drag on for ten more. Fleets of ships of the line cruised for up to six months at a time back and forth along the same stretch of coast, through weather foul and fair, through spring, summer, and fall, and all through the winter gales, hoping to tempt a smaller force of enemy ships out into a battle to capture or destroy them. Fast-sailing frigates, cutters, and sloops prowled close to land, spying for evidence of a fleet leaving port, and rushed back to communicate with the ships of the line stationed farther out to sea. Transport ships occasionally brought new lemon juice supplies to the fleet. Through fortune of geography, Britain was in a position to dominate the seas of western Europe and block other European ships from crossing the Atlantic, and when storms lashed the coast, blowing blockading ships off station, the prevailing winds kept French and Spanish ships from leaving port.

This kind of operation was tiresome and tedious work for the tens of thousands of mariners crammed together on their ships with only their duty to keep them occupied. Although warships had grown in size throughout the century, so did the number of men needed to sail them. Anson’s flagship, the Centurion, in the 1740s held sixty guns and about six hundred sailors, while at the Battle of Trafalgar sixty years later Nelson’s flagship, Victory, had one hundred guns and more than nine hundred sailors. Larger, more heavily manned ships, combined with the need to remain at sea for months at a time, multiplied the critical responsibility for effective provisioning. At one time, ships were refitted and reprovisioned in the winter following the summer battle season, as was the case when Blane first sailed to the West Indies in 1780. During the wars with revolutionary and Napoleonic France, however, ships were in action year-round to keep up the blockade.

The diminutive Corsican general Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) was a military genius who seized power in France in the late 1790s. He finally dispensed with the egalitarian ideals of the French Revolution altogether and crowned himself emperor in 1804.

The blockade had thwarted several small-scale invasion attempts before 1805. In December 1796, more than thirteen thousand French troops and seventeen ships of the line cruised off Bantry Bay in Ireland but did not land. They were waiting for the Irish revolutionaries to revolt and feared retaliation from the larger Channel fleet. In 1798, after the Irish rebellion, twelve hundred French troops did land at Bantry Bay, but they were taken and reinforcements by sea were blocked by the Royal Navy. In 1797, a small French force came ashore in Wales but was also hastily defeated. In October 1797, Napoleon ordered the construction of the flat-bottomed invasion barges to transport his troops across the Channel. The threat of invasion was real and direct and tangible, and the long-suffering mariners of the Royal Navy were called upon as never before to defend their homeland.

By 1805, Napoleon’s invasion army had been camped in northern France for nearly two years, and in March of that year, he issued orders to combine the disparate components of his navy into a mighty battle fleet that would then provide safe passage for his troops across the English Channel. He ordered Admiral Villeneuve in Toulon to evade the blockading Mediterranean fleet, sail west to Cadiz, drive away the smaller British squadron, liberate the Spanish ships, and quickly flee across the Atlantic to Martinique. Admiral Honoré- Joseph Ganteaume was to sally forth from Brest, escaping the Channel fleet, and proceed south to the northern Spanish port of Ferrol, liberate the fleet contained there, and head to the rendezvous in Martinique. And Admiral Edouard Thomas Missiessy was to lead the French fleet from Rochefort directly to the rendezvous. If all went according to plan, Napoleon’s grand fleet would comprise about eighty ships of the line and more than twelve

frigates. By crossing the Atlantic first, Napoleon hoped to cause some damage to British shipping in the West Indies, but most important he hoped to confuse the British fleets and conceal his true intentions. The grand fleet was then to recross the Atlantic and cruise up the English Channel in sufficient force to crush the Channel fleet and secure the strait for his troops. It was a strategically sound plan that would have worked had it not proved impossible for many of his ships to escape the British blockade.

Ganteaume’s twenty-one ships of the line were met by a superior British force each time they manoeuvred out of Brest and so were unable to free the nine warships in Ferrol and proceed to Martinique. Although Missiessy succeeded in crossing to Martinique with his five warships, he grew tired of waiting for the other squadrons and returned to Rochefort when they failed to rendezvous in May. Villeneuve and his warships successfully eluded the Mediterranean fleet, freed the Spanish warships at Cadiz, and crossed to Martinique, but they arrived after Missiessy had returned to Rochefort. Villeneuve then received new orders to prey on British shipping in the West Indies for a month before sailing to relieve the ships at Ferrol and then Brest, and continuing with the invasion plan. In June, however, he learned that Nelson and the Mediterranean fleet had followed him west across the Atlantic, after first searching for him near Egypt, and so he departed immediately, hoping to elude them again. Villeneuve’s month-long voyage back to Europe was disastrous, with storms, scurvy, and fevers killing a thousand of his sailors and weakening thousands of others. On July 22, in thick fog near Ferrol, he encountered a small British fleet of fifteen warships under Sir Robert Calder. Disoriented, with damaged ships and weakened men, Villeneuve fought to escape after losing two ships and then retreated to the nearby port of Vigo, where he recuperated and repaired his damaged fleet. Villeneuve knew that pressing on with the original plan would be hopeless, as the entire British fleet now knew of the invasion scheme and would be lying in wait at

the entrance to the Channel. He decided to cruise south to Cadiz, arrivingon August 22—four and a halt months after leaving Toulon, most of which had been spent at sea.

On September 28, Napoleon ordered Villeneuve to return with his fleet of thirty-three warships to the Mediterranean to help transport troops to Naples. Nelson and a twenty-seven-warship battle squadron waited offshore, and they clashed on October 21, off Cape Trafalgar. By that evening, nineteen of the French and Spanish ships had been destroyed or struck their colours and surrendered. Others burned, and in the coming days several more were taken or destroyed. The remainder of the combined fleet limped back to Cadiz, leaving the British victorious. But the victory was tempered by loss. At four-thirty in the afternoon, the great commander Nelson, the man who had led British fleets on their greatest string of victories in history, was blasted through the chest by a sniper. He later expired in the gloomy sweat- and blood-soaked cockpit deep in the bowels of his battered flagship. “Thank God I have done my duty,” he reputedly gasped with one of his final breaths.

Trafalgar would be Nelson’s greatest victory. The death toll was tremendous: 448 British seamen were killed and 1,241 wounded, while 4,408 French and Spanish were killed and 2,545 wounded. Another 14,000 French and Spanish were taken prisoner. A day after the terrible engagement, the wind picked up and pulled whitecaps from the turbulent sea. A great storm was brewing—a natural counterpart to the bloody massacre. Dark clouds rolled in from open water, wind shrieked in the rigging, and the sea surged, sucking the ships towards a rocky lee shore. Many of the ships were already badly damaged, with masts cracked, rigging tangled together, sails shredded, and water flooding through holes in the hull—not the best conditions for riding out a storm. And with the great number of casualties and prisoners, many of the ships could not be fully manned. For days the storm raged, and eventually the British officers ordered the tow cables to several of the French and Spanish

prizes cut. They were turned loose into the storm, some with wounded mariners still struggling to survive in the dank holds. Only a handful of Napoleon’s ships escaped the disaster of war and natural calamity. At Trafalgar the British tore the heart out of Napoleon’s navy, and the defeat of scurvy had played a significant role in their supreme victory.

Many of the naval commanders who led the Royal Navy to victory at Trafalgar were old enough to remember a time when scurvy was as great a foe, and perhaps more feared, than the enemy. Nelson himself nearly perished from the disease in 1780, when he was twenty-two years old and had been promoted despite his youth to captain of the twenty-eight-gun British frigate Albemarle during the War of American Independence. The ship had been eight weeks at sea, voyaging to Quebec for convoy duty. As the disease took hold, the young captain and his men became weakened and melancholy. Dark splotches appeared on their skin, and their gums began to swell painfully. The only food they had was salted sea rations, and they were in danger of perishing, leaving the ship a drifting bonebed. Before anyone had succumbed to the dreadful affliction, however, they were miraculously delivered from their predicament by the appearance of a small American vessel from Plymouth, Massachusetts. The American captain, perhaps pitying their miserable condition, graciously shared with them some live chickens and fresh vegetables. The men soon recovered, and the Albemarle continued on its voyage to the St. Lawrence. Fortunately, the foods and climate of Quebec, very near to where Jacques Cartier and his crew suffered from scurvy two and a half centuries earlier, was sufficient to recruit the young captain’s constitution. “Health,” Nelson wrote to his father, “that greatest of blessings, is what 1 never truly enjoyed till I saw fair Canada.”

The Battle of Trafalgar on October 21, 1805. The British tore the heart out of Napoleon’s navy and thwarted the invasion of England. The defeat of scurvy played a significant role in their supreme victory.

When Nelson died at Trafalgar, he was at the pinnacle of a brilliant naval career. He was Britain’s greatest commander, a national hero associated more closely than any other with naval supremacy during the Age of Sail. During the era of his stunning victories, in the late 1790s and early 1800s, scurvy was no longer a threat to the Royal Navy. It had been reduced to a menacing phantom, rarely occurring since Blane had persuaded the Admiralty to issue a daily dose of lemon juice as a preventative in 1795. Yet Nelson might easily have perished, like many others, before ever realizing his potential. Perhaps remembering his own encounter with scurvy as a young captain, he was devoted to the health of his men, which he knew contributed to the strength of his fighting force. He purchased additional supplies of lemon juice, above the Admiralty’s regular issue. In February 1805, just a month before he set off on the pursuit of Villeneuve that culminated in the Battle of Trafalgar, he ordered for the Mediterranean fleet an astonishing twenty thousand gallons of lemon juice to supplement the regular issue of thirty thousand gallons. Despite having been months at sea without any significant time in port, the British sailors at Trafalgar were free from scurvy.

Although the Battle of Trafalgar was a stunning victory for Britain, the blockade strategy had already come to fruition a month earlier, on August 27, when Napoleon, realizing the total failure of his plan to combine the disparate fleets of his navy, ordered his invasion army in northern France to decamp to Austria, leaving Britain in command of the sea and free from the imminent threat of invasion. The blockade was a devastating strategy that kept Napoleon out of England and led ultimately to his defeat ten years later. “Those far distant, storm-beaten ships upon which the Grand Army never looked,” wrote the naval historian Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, “stood between it and the dominion of the world.”

Napoleon had thought it would be impossible for the British to maintain a year-round blockade. It was a terrible strain on Britain’s naval resources and shipyards. It was also a terrible strain

on Britain’s seamen, and would have proved an unbearable strain had scurvy not been virtually eliminated from Royal Navy ships. Only the blockade stood as a bulwark against Napoleon’s armies, and the fleet could not have done its job if the warships were continually scuttling back to port to discharge thousands of scorbutic sailors into hospitals and wait for them to regain their health before setting out again.

A single crippling incident such as what Lind dealt with in August 1780, when twenty-four hundred scorbutic mariners were landed at naval hospitals despite orders to keep at sea, could have broken the defence of the island and given Napoleon the opportunity to launch his invasion. But with the defeat of scurvy, the warships of the Royal Navy never deserted their posts and the majority of Napoleon’s navy was kept bottled up in half a dozen separate ports throughout the war. The blockade disrupted France’s commerce and communication with her colonies, damaged the French economy, and weakened the country’s capacity to pay for the ongoing war. The British economy, on the other hand, although fluctuating throughout the war, grew stronger as its exports and imports flourished with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Having the run of the sears, the Royal Navy protected Britain’s colonial interests while starving and isolating those of her enemies.

By the early nineteenth century the Royal Navy was consuming fifty thousand gallons of lemon juice annually, most of that coming through the naval base at Malta, one of the few Mediterranean ports not blocked by the French or the Spanish. Between 1795 and 1814, more than 1.6 million gallons of lemon juice were issued to Royal Navy ships. The juice was stored in bung-tight casks under a layer of olive oil, which although not a perfect preservative over a long time period retained enough ascorbic acid to fend off the advances of scurvy. Fresh lemons were salted, wrapped in paper, and stored in light crates or prickled in sea water or olive oil, their juice squeezed shipboard by the cook or the surgeon’s mate to be added to the grog. For the first few years after 1795, lemon juice was merely issued on demand to ships and fleets. In 1799, however, daily lemon juice became official issue to all ships of the Royal Navy because of the persuasions of Thomas Trotter, the physician of the Channel fleet, and Gilbert Blane’s continued agitations. It was expensive, but the benefits far outweighed the cost.

Horatio Nelson (1758–1805) was Britain’s greatest naval commander, a national hero more closely associated than any other with naval supremacy during the Age of Sail. During the era of his stunning victories in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, scurvy was no longer a threat to the Royal Navy.

The transformation of the health of British seamen following the introduction of lemon juice was immediate and remarkable. During the nine years of the War of American Independence, for example, the average annual ratio of sick and hospitalized mariners was about one in four, but in the nine years following 1795 the figure had been reduced significantly, to roughly one in eight. The naval historians Christopher Lloyd and Jack Coulter have made an interesting comparison of the incidence of fevers and scurvy at Haslar hospital. In 1782, scurvy afflicted 329 men per thousand while fever affected 112 men per thousand. In 1799, however, the proportion of men hospitalized with scurvy had fallen to 20 per thousand while fever had increased slightly to 200 per thousand (although fever was also on the decline by the early nineteenth century, owing to improved shipboard hygiene). Before the turn of the nineteenth century, scurvy accounted for less than 2 percent of mariners in the Royal Naval hospitals.

“Other causes,” Blane wrote decades afterwards, “particularly the improved methods by which fevers were diminished, contributed greatly to this decrease of sickness, so that it may be difficult to assign precisely what is due to lemon juice. But what admits of no ambiguity, is that, ever since the year 1796, scurvy has almost disappeared from ships of war, and naval hospitals.” By the early nineteenth century, most of the Admiralty sick lists did not even include scurvy as one of the common and standard sea diseases. Dr. John Lind, the son who took over Haslar hospital when James Lind resigned, informed Blane in 1815 that he had seen only two cases of

scurvy in the final four years of the war. Trotter wrote in 1802 that during his early days in the Royal Navy, “it was no uncommon thing in those times for a ship during an eight week cruise to bury 10 to 12 men in scurvy, and land fifty at a hospital.” But he noted that now when scurvy appeared, it was quickly treated.

The state of the fleet during the Nelsonian era of British naval supremacy was poles apart from its condition a mere two decades earlier, when Lind presided over the hospitalization of thousands of mariners of the Channel fleet in 1780. The Channel fleet, wrote Blane, “was overrun with scurvy and fever, and unable to keep the sea, after a cruise of ten weeks only; and let the state of this fleet be again contrasted with that of the Channel Fleet in 1800, which, by being duly supplied with lemon juice, kept the sea for four months without fresh provisions, and without being affected with scurvy.” Blane observed with great understatement that “the year 1796 may therefore be considered as an era in the history of the health of the navy.”

In the preface to an 1853 reprint of the narrative of George Anson’s voyage, the editor, after discussing the horror of that particular bout with scurvy, wrote that “the reader will be satisfied to learn, that the fatal disease which reduced Anson’s squadron to extremity, and has caused the loss of tens of thousands of our seamen, is now scarcely known either in public or private ships belonging to Great Britain. A due regard to cleanliness, warmth, and ventilation, but, above all, the free use of lime juice, or other acids, with fresh meat and vegetables as often as they can be procured, have almost, if not quite, annihilated the scurvy, which now but rarely appears, except under circumstances where these precautions are neglected, and may be said to exist only in the painful memory of those who have witnessed its fatal devastation.”

Although it is difficult to quantify the specific impact of the defeat of scurvy on the outcome of many of the key naval battles and engagements of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars,

there can be no doubt that it played a significant role. In addition to enabling the blockade, it ensured that experienced British seamen didn’t perish at an unsustainable rate during the years of the blockade. Blane calculated that if the severe mortality rate of British sailors during the War of American Independence had continued during the twenty-two-year conflict with France, the Royal Navy would have run out of sailors. “The whole stock of seamen would have been exhausted,” he wrote, “in which case men would not have been procurable by any bounties however exorbitant; for it has been stated, that if the mortality of 1813 had been equal to that of 1779, there would have died annually six thousand, six hundred and seventy-four men more than have actually died: which in twenty years would have amounted to 135,480, a number very nearly equal to the whole number of seamen and marines employed in the last years of the war.” If scurvy had continued to cull British seamen at its usual rate, the manpower of the Royal Navy would have been insufficient to meet the challenge of the prolonged war with France and the stresses of blockade duty. Britain had a population of only about nine million at the time, while France had more than twenty-five million. Writing after the Napoleonic Wars, the naval surgeon Robert Finlayson commented, “It is the opinion of some of the most experienced officers that the blockading system of warfare which annihilated the naval powers of France could never have been carried on unless sea-scurvy had been subdued.”

The victory over the most malignant and destructive of maritime diseases was so complete that within a few years of Blane’s recommendations being implemented, scurvy had lost its deadly and sorrowful connotations in the Royal Navy. It still cropped up occasionally on ships that were unable to obtain lemon juice or whose supply ran low on long voyages, but it was no longer the universally dreaded killer it once had been. Scurvy had been defeated.

Throughout the battles of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the ships of the Royal Navy routinely defeated the French. Not only were the British sailors mostly disease-free but the crews were better trained and more experienced, owing to their extensive time at sea. France had a shortage of experienced officers because many were of aristocratic lineage and so were killed or exiled during the revolution. The surviving officers and crews gained little sea experience while locked up in port by British blockades, so when they did emerge and engage British ships, they were outmanoeuvred and outgunned. The Royal Navy had better officers and stricter discipline, and the crews were highly motivated, partly by the prospect of prize money from captured ships. The French needed great numerical superiority to have even a fighting chance against the precision machines of the Royal Navy. At Trafalgar, for example, the Spanish ships contained a large number of recently pressed men from the slums of Cadiz, many of the gunners had never practised firing from a ship rolling at sea, and a typhus epidemic raged throughout the fleet. The Spanish captains also resented being under the command of a French admiral. It is not surprising that they lost the battle, Nelson’s innovative tactics aside.

Blane wisely pointed out that “it must however appear clear to every reflecting mind, that the care of the sick and wounded is a matter equally of policy, humanity and economy. Independently of men being sentient beings and fellow creatures, they may also be considered as indispensable mechanical instruments.” If the “mechanical instruments” that powered and controlled the ships and guns were faulty, in disrepair, and generally in poor and unreliable condition, then the overall fighting force would also fail to achieve its potential. It doesn’t take great imagination to picture the outcome of a battle between two ships of the line of equal size and armament, one with a vigorous, strong, and motivated crew, the other with a third of the mariners weakened, debilitated, and morose with scurvy.

There is evidence that the French and the Spanish knew of the antiscorbutic powers of citrus fruit but lacked the political will to implement the cure on an institutional level. A Spanish naval physician, Don Antonio Corbella, for example, wrote of his experience with scurvy in the hospital in Montevideo in 1794. A ship had crossed from Cadiz with “all its crew and staff infected with scurvy” to such an extent that “when they fell on the floor they could not get up and to many it was necessary for the nurses to feed them.” Although Corbella prescribed a laxative “to clean the stomach and the first part of the large intestine from putrid material which are formed there,” he also made “abundant use of lemonade” and “pure lemon juice … according to the strength of each one.” The ship’s surgeon had lacked the resources to cure the sailors during the voyage, and it was only when they reached port and the hospital that Corbella “was able to destroy this terrible disease and to free those unfortunate fellows who could now continue their voyage.” Unable to benefit from the fundamental institutional restructuring that had eliminated scurvy in the Royal Navy, the French and Spanish crews continued to be ravaged by the disease on long voyages.

Without the political will to change centuries-old traditions in victualling and the education of surgeons, no large-scale cure of scurvy would have been possible for any nation. Napoleon was a brilliant strategist, but his focus was always on land and his interest in the navy was primarily as a means to move his troops and to tie up Britain’s resources. If he had turned his strategic mind to reforming his navy, as he had reformed the organizational structure of his armies, the French and Spanish fleets would almost certainly have fared better in many of the numerous smaller-squadron or single-ship actions of the war. An invasion of Britain, however, would still have been dependent on breaking the Continental blockade and seizing naval control of the Channel, which would have been impossible without the failure of the Royal Navy.

Because of the blockade, a majority of French and Spanish ships spent most of their time in or close to port, seldom setting off on long voyages and so seldom suffering from scurvy. When they did venture forth on extended trips, such as during Pierre Villeneuve’s evasive cruise across the Atlantic and back in 1805, scurvy and other diseases eventually caught up with them. Napoleon never initiated a naval blockade of British shipping or ports, so the discovery of a cure for scurvy would have had little tangible impact on his naval strategy. The historian Richard Harding writes in Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650–1830 that “the practical problems of engaging in a trade blockade based upon squadrons of large warships were too great to be considered a reasonable employment of the state’s resources. Britain was probably alone in that a trade blockade converged with policies that were essential for its own survival—defence of its own trade and territorial integrity—and thus possessed the political will to develop the resources that made such a blockade possible.” The ball was in Britain’s court. The terrible outcome from not discovering a cure for scurvy on Royal Navy ships—an inability to effectively maintain the two-decade blockade of enemy ports—would have been borne by the British alone, just as the cure for scurvy provided them with the greatest benefit, their very survival as a nation.

What if Britain had discovered scurvy’s cure a decade and a half earlier, just after Cook’s return from his second voyage, when the evidence in favour of citrus juice and against wort of malt should have been compelling? Blane observed that by the early nineteenth century, it was commonly accepted within the navy that because of the reduced death toll and the improved health and strength of mariners after 1795, two ships of war were more powerful than three in “former times.” “When the Fleet could not keep the sea for more than ten weeks without being unserviceable by scurvy,” Blane wrote, “another force as nearly equal as possible had to be available

to replace it.” The former times that Blane referred to included the War of American Independence, during which, as we have seen, the Channel fleet in particular was in a shambles because of scurvy. A mere ten years separated that war and the Napoleonic Wars. The naval historians Christopher Lloyd, and Jack Coulter have concluded that “the state of the navy from a medical point of view was so bad between the years 1778 (when the war became general) and 1783 that it must be accounted partly responsible For the defeat which Britain suffered.”

What might have been the outcome of the War of American Independence had lemon juice been the official antiscorbutic at that time instead of the ineffective wort of malt? With the Royal Navy unhindered by scurvy, and the ships a third stronger in terms of manpower, would the entry into the war of France and Spain on the side of the American colonies have been great enough to secure their independence from Britain? The practical example of the Royal Navy’s blockade potency against Napoleon is compelling. The historian Paul Kennedy has noted in The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery that the British decision not to implement a blockade of France in 1778, which would have been virtually impossible without first solving the problem of scurvy, allowed “free egress for all the French squadrons which were dispatched to assist Washington, to intervene in the West Indies … . The saving of wear-and-tear on British warships simply transferred the problem of establishing naval control to more distant seas.” If the Royal Navy had been able to maintain a naval blockade of France and Spain as effective as the blockade that proved so devastating during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, a large French fleet would not have been able to freely cruise the Caribbean and sail to the aid of Washington’s army on the shores of Chesapeake Bay in 1781. Without the pressure wrought by several thousand French troops and twenty-eight ships of the line, General Charles Cornwallis probably would not have surrendered at Yorktown on October 22 and effectively

guaranteed the independence of the American colonies. Kennedy notes that “the interventions of the French navy, in the Channel, off Gibraltar, in the West Indies, off Yorktown, had clearly played a considerable part in Britain’s failure to win the war in America.”

It can be argued that just as Britain owes its success against Napoleon and the dominance of the seas to the sagacity and perseverance of Gilbert Blane in 1795, the Thirteen Colonies and their allies in the War of American Independence owe their success against Britain to the overweening, stubborn pride, or wilful blindness, of Sir John Pringle, who influenced the Admiralty in favour of an antiscorbutic regimen that had little effect in reducing scurvy, which in turn severely weakened the strength of the Royal Navy.

Historians have pointed out that it is unlikely that the British could have held on to America indefinitely, regardless of their determination and strategy. Kennedy, for example, notes wryly that “by 1778 there were over 50,000 troops in North America and they were showing singularly little sign of achieving victory … . Even if the main rebel forces had been annihilated, there remained the difficulty of preserving this dominance over a resentful, populous and resourceful American people under such arduous geographical and logistical circumstances.” The war in America was an organizational nightmare for the British, with all the supplies for both the army and the navy coming, at unpredictable intervals, across the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean. As well, the British fleet had been allowed to deteriorate after the Seven Years’ War, and in the American Revolution, unlike previous wars, Britain fought without Continental allies to occupy France and Spain. The Americans were fighting for their homeland, and the determination of the colonists to shake off Britain’s yoke would have made it nearly impossible to subdue them indefinitely.

Bur with an effective British blockade of American, French, and Spanish ports, the American colonies would have had their victory delayed for years and would have agreed to different terms at the

eventual peace conference. At no other point in history did scurvy have the ability to affect world events to such an extent. In times of peace, the secret of scurvy’s cure would have spread quickly between navies and merchants, simply because sailors always changed ships and talked with others in their profession. But during the cauldron of war in Europe in the late eighteenth century, the timing of Britain’s discovery and implementation of a cure for scurvy on an institutional level in the national navy changed the course of world history.

In terms of its larger impact on world affairs, Blane’s daily ration of lemon juice for mariners was perhaps the single greatest medical and socio-military advancement of the era. After the defeat of Napoleon, Britain’s position as the leading European, if not world, power was assured—with this terrible bloodbath, the country was propelled to the pinnacle of political and commercial dominance, the only superpower of the era and the maintainer of “the peace of Britain.” The Royal Navy emerged as the strongest fleet on the globe, but, free from scurvy, the seas were opened to commerce, travel, and exploration for many nations. Knowledge of the practical cure for scurvy would have spread quickly once regular commerce and travel resumed in Europe—and it was a crucial development for world prosperity. With a lower death toll of mariners on long voyages, the expense of manning ships and shipping goods was greatly reduced. Without scurvy tethering ships to port, global trade expanded throughout the nineteenth century, fuelling the Industrial Revolution. Medical reasoning began a slow departure from the theoretical foundations that had stultified practical inquiry for centuries. And tens of thousands of lives all over the world were saved. The defeat of scurvy, and the concomitant increase in the time ships could spend at sea, was the keystone in the construction of the British-dominated global trade and communication network that flourished throughout the nineteenth century.

Many of the other technological improvements of the Nelsonian era, such as standardized signalling, copper sheathing on the hulls of ships, and the calculation of longitude through the use of an accurate naval chronometer, would have been of little practical use if the health of seamen had not also been correspondingly improved. “Without the supply of lemon juice,” Blane wrote, these advances which “do honour to the human intellect, particularly to the age and country in which we live, would be in a great measure frustrated.” What good was the ability to accurately calculate longitude and thereby remain at sea indefinitely if the mariners perished from scurvy because of it? What good would have been bigger merchant ships for transporting greater quantities of goods on longer voyages between ports if the sailors’ health was insufficient for the task?

The conquest of scurvy was certainly not the only factor in Britain’s defeat of Napoleonic France or her subsequent commercial expansion and rise in global power. Historians have studied and written in great detail about the complicated blend of factors, including geography, natural resources, taxation policies, government, and economics, that resulted in Britain’s preeminence in the nineteenth century. But the conquest of scurvy is an underappreciated foundation upon which these other achievements were built. It has been observed by the historian S. R. Dickman that “one might say the British Empire blossomed from the seeds of citrus fruits.” And given that the empire was maintained in great part by the effectiveness of its fleet, it is hard to disagree. The conquest of scurvy as a widespread occupational disease in the Royal Navy, and later for all the world’s mariners, was a crucial link in the chain of events that has led to the world as we know it.