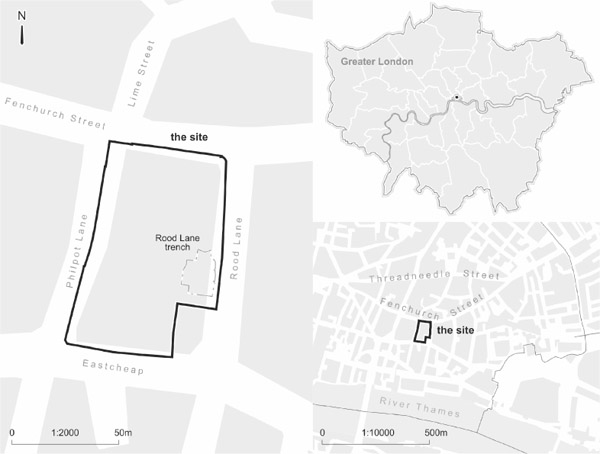

Figure 27.1 20 Fenchurch Street: site and trench location (left). © MOLA.

As the Great Fire of London raged through the narrow, mainly wooden-built streets of London in September 1666, it reduced all the buildings and businesses on Rood Lane in the eastern part of the city of London to cinders. Here, as elsewhere in the city, new buildings soon grew up on the site, mirroring precisely the same property demarcations as the old street. A cycle of partial reconstructions and renewals continued over the next couple of centuries until, in 2008, a major new build was planned (Figure 27.1). But this reconstruction took place in a very different disciplinary and legislative planning environment, requiring construction companies, once they had cleared the site, to allow archaeologists a period of investigation before building could go ahead.1 Consequently, after the previous building was demolished, a team of archaeologists from MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) proceeded to uncover the extended history of Roman to seventeenth-century London that had survived and lain long forgotten in the ground below.

The MOLA team however discovered that, far from destroying everything in its wake, the heat of the Great Fire had caused one wall of a brick-lined cellar in the Lane to collapse inwards, sealing its original contents in situ and largely intact (Figures 27.2 and 27.3).

Subsequent identification, cataloguing and analysis of the remarkable contents by a raft of MOLA artefact specialists, including one of the current authors, led to the finds being interpreted as indicating a retail drinking establishment on the site.2 The Rood Lane cellar materials included up to 20 stoneware bottles and six to eight pitchers imported from the town of Frechen in the Rhineland,3 up to four black-glazed redware mugs that were probably Essex manufactured,4 11 clay tobacco pipe bowls of the later seventeenth-century bowl type5 and a number of immensely delicate sherds (or shards) of several hand-blown and trailed façon de Venise glass cylindrical beakers6 in addition to a similar enamelled vase, an object which provided more difficult to parallel.7 As is typical of most archaeological digs, no pewter or silver objects were found in the cellar. Though such valuable objects were certainly present in many metropolitan retail establishments, they were valued as objects for display as well as use and were unlikely to have been stored out of sight in a cellar such as this.8 It is always possible, however, that such items were simply removed in the post-fire era by builders involved in the long cycle of city reconstructions, which could equally account for their absence throughout the archaeological record, a question to which we will return.

In this chapter, two scholars, one an archaeologist specialising in glass, clay tobacco pipes and ceramics and the other a historian of drinking and its material culture have come together to discuss how, from their different but complementary disciplinary backgrounds, they might approach these remarkable finds. Given the short space available, we have focussed in particular on a single sherd (as an archaeologist would have it) or shard (as a historian might) of one of the façon de Venise cylindrical beakers recovered from the cellar (Figure 27.4).9

How does the archaeologist approach the sherds (or shards) of pottery and glass that appeared among the items in the cellar? The present-day landscape of archaeology in the UK is a relatively new one. Its emergence as a profession from its antiquarian origins was spurred by the need to record the unprecedented quantity and diversity of archaeological sites and remains uncovered during the post-war reconstruction of Britain’s bombed towns and cities. This coincided with the foundation of departments dedicated to its academic study among the new universities and colleges. As a practice, archaeology has a long and illustrious history, one that has had an enormous impact on the discipline, moulding the questions and approaches taken by modern scholars and practitioners. While for historians the seventeenth century is central to the ‘early modern’ period, for archaeologists it falls within the much longer ‘post-medieval’ period of study, a term which covers the ‘archaeology of late medieval to industrial society to the present day’,10 which, since the 1990s, has witnessed significant developments, especially the emergence of ‘a renewed self-confidence in the distinctive perspectives of archaeology in all forms, and its abilities to combine alternative approaches’.11

The methods of the archaeologist are scientific and orderly. During excavation, the focus is to recover artefacts and eco-facts (animal, vegetable and mineral remains). Deposits are carefully recorded in order to understand the site’s taphonomy (the study of processes which affect organic materials such as bone after death) and stratigraphication (the laying down or depositing of strata or layers one above the other which should provide a relative chronological sequence).12 After excavation, the artefact specialist views and rigorously catalogues the objects (which are usually only partial) by their material (for example ceramic, glass, copper alloy, bone); by object type (for example belt-buckle, hair-pin, comb) or form (for example bottle, jug, bowl, plate). Accurately determining the object type or form is critical in assessing its function and is achieved by comparing careful observation of the object against a battery of published typologies that place particular classes of material into either chronological or developmental sequences in order to map design and technological change.13 While the function of a lowly cellar in early modern London and what it contained may not appear a particularly attractive subject to most, to archaeologists cellars are important spaces. As almost all the city’s above-ground buildings of timber-framed construction were destroyed in the conflagration that swept through London during that fateful first week of September 1666, the majority of the archaeological evidence for the Tudor and Stuart metropolis has commonly survived in either wholly or partly subterranean cellars by virtue of their stone or (later) brick construction.14 In the case of the Rood Lane cellar, many of the stone bottles and the earthenware mugs survived as large joining sherds, so that a considerable proportion of these vessels could be fully or almost fully reconstructed; this is significant as it suggests that most were perfectly useable at the time of the cellar wall’s collapse. The glass sherds (or shards) had belonged to several different vessels, but although they are individually quite large – for example, a whole glass foot, or as in our case study, a whole foot and large glass section – they were much less complete than the bottles and mugs. This may have been because they were more vulnerable to crushing or the remaining pieces were perhaps so small or fragile that they were not retrieved during excavation.

Archaeologists are extremely familiar with taphonomic questions arising from objects that have been discarded as rubbish but, unusually, these objects had been sealed under a collapsed wall, presenting a very different set of questions and possible conclusions. By looking carefully at the types of materials that were present, the archaeologists were able to reconstruct a sense of this place when it was thriving and not when it had already come to an end. But what kind of a place was it? Soon after its discovery, it was presumed that the Rood Lane site represented a retail-drinking establishment, but was it a lower-scale alehouse, an up-market tavern or a much more elaborate establishment such as an inn?15 The placement of the cellar and the building it once served, located halfway down a narrow medieval street, would not have been a suitable place to site an inn, as these premises were usually situated on wider thoroughfares and required large courtyards for stabling and coaching facilities and other infrastructure.16 The function of this property could not be determined through the surviving historical administrative archive; a reminder that the coverage afforded by documentary evidence is often just as fragmentary as the sherds (or shards) of glass in the cellar. Consequently, the interpretation of the ‘assemblage’ and the functions it implied took centre stage in the investigation.

Overall, the composition of the Rood Lane cellar assemblage in terms of the range of materials represented, the function of the objects and their (largely foreign) source of supply was found to be very similar to the make-up of two other assemblages from previous excavations definitively linked to known drinking spaces in London: the storage vaults of the Guildhall (the principal administrative and commercial centre of the city of London) and the cellars of The Bear Inn, in Basinghall Street.17 Critically, like the Rood Lane property, these sites were both destroyed by the Great Fire of London, and the stock of ceramics, glass and pipes discovered in their cellars reflect their contents at the point the buildings above were consumed by flames in September 1666. By comparing the Rood Lane finds with the fixed points afforded by the Guildhall and the Bear Inn assemblages, we can see that all three premises offered almost the same range of vessels to their customers (Rood Lane and Bear Inn) or at banquets (Guildhall), with ales, beer and perhaps wine served in black-glazed mugs, stored and poured from the ubiquitous German stoneware bottles of the period. Additionally, all three premises contained varying quantities of smoked clay tobacco pipes.18

A feature of the assemblages in all three sites was the remarkably international sources of supply for most of the ceramic and glass. In Rood Lane, many of the stoneware bottles were decorated with medallions depicting the commonly applied arms of the Duchy of Julich Kleve-Berg and the City of Amsterdam, alongside traditional bearded face-masks.19 While Frechen stonewares are among the most recognisable and ubiquitous finds in mid-sixteenth- to seventeenth-century dated archaeological sequences in London and elsewhere (on sites as geographically diverse as Amsterdam, the American colonies and the Caribbean) the archaeological record suggests that the quantities of glass bottles in circulation in the pre-Fire capital were rather limited. While glass recycling could be an important factor here, the typical glass containers (known as ‘shaft and globe’ bottles) of the newly founded English bottle industry in our noted London retail drinking establishments – Rood Lane, the Guildhall and the Bear Inn – were limited to a few examples in the cellars of the Bear Inn.20 Yet common to all three premises was a small quantity of glass cylindrical beakers of façon de Venise style.

Though they were incomplete, archaeologists reconstructed the shape of the original glass beakers among the Rood Lane assemblage through drawings based on indications of the glass fragments themselves and other published examples found elsewhere from excavations in England.21 These were then catalogued ready for publication.22 The sherd (or shard) being considered here (Figure 27.4) survived as a complete base, with some part of the glass. It was made of a good quality colourless light-grey tinted glass and decorated with opaque white glass vetro a fili spiral trailing, a technique also applied to the underside of the base.23 It was thought to be most comparable to a cylindrical beaker with an applied rigaree-patterned base-ring of the type depicted by archaeologist Hugh Willmott, who considered it to have been imported from the Low Countries, where it was commonly made.24 Low Countries origins also seemed most likely in that our sherd does not match the London-made products by late-sixteenth-century immigrant Venetian glassmakers Jean Carré or Jacob Verzilini.25 These houses certainly made Venetian-style drinking glasses, but archaeological evidence for their products has either not survived or is yet to be determined. A few surviving examples attributed to Verzelini’s stewardship are displayed in museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum or in private collections, but these do not match our object.26 The same can be said for the seventeenth-century glassware made in the Broad Street, London, glasshouses of Robert Mansell and Jeremy Bowes.27

Could the cellar itself have been a space for drinking? Its function could not be determined through the archaeological evidence: the cellar was found in a partial and fragmented state with no evidence of fixtures and fittings and could only be partly excavated, as the remainder survives under the present day Rood Lane. Other sources were therefore used in order to determine the possible range of functions it might have had. In Schofield’s analysis of Ralph Treswell’s various London Surveys of property made between 1585–1614, he found just two examples of cellars being used as anything other than storage spaces (one a kitchen and another a dwelling).28 Cellars were often accessible from the outside; some had trapdoors, but many had short stairs leading up to the street.29 Inventories, though not a straightforward source, do provide further evidence hinting at what cellars typically contained and make it clear that at least some functioned as drinking places. Historians often turn to contemporary diarists, such as John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys, for understanding the rituals and routines of drinking; both diarists refer to visits to Thomas Povey’s well-appointed wine cellars in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where it can be presumed they took a glass or two from the wine bottles kept there.30 Similarly, Pepys noted many instances of communal drinking in other cellars (not least his own), for example joining ‘My Lord (Sandwich) with Colonel Strangeways and Sir Richard Floyd, Parliamentmen, in the cellar drinking, where we sat with them’,31 in addition to taking wine with Mr Dalton in the old wine cellars at Whitehall, for example, when on 5 January 1663 Pepys ‘took Sir W. Batten and Captain Allen into the wine cellar … and there drank a great deal of variety of wines, more than I have drunk at one time, or shall again a great while’.32 If more ordinary cellars too were used as drinking spaces, perhaps small quantities of glass were kept there just for that purpose?

Archaeological practice tends to place significant weight on an ‘assemblage’ as a whole. Indeed, this was important in the case of Rood Lane, as it enabled the comparative framework by which this collection of objects could be linked to the Guildhall and the Bear Inn. However, an emphasis on the collective can serve to muffle the role an individual pot or glass vessel may have had. While the glass, ceramics and pipes with their emphasis on drinking and smoking in the Rood Lane cellar were a) clearly stored together, and b) have thus been considered together as an assemblage, do these objects look as if they would have been used together in the same space and at the same time in the rooms of the building that once stood above? This is just the sort of question a historian might ask.

How does a historian of drinking and its material culture approach the questions raised by this glass shard (or sherd), entombed in a cellar alongside its stone- and earthenware companions in 1666? The idea of learning history from things is, of course, by no means new, but the incorporation of artefacts and the analytical methodologies used to study them is steadily becoming an important feature of economic, cultural, religious and political historical approaches, amounting to a ‘material turn’ to follow the literary and visual ‘turns’ of earlier years.33 One leading influence in promoting a material approach to early modern history over the last 30 years, at least in Britain, has been the extraordinarily interdisciplinary field of history of design, in particular emanating from the postgraduate programmes run by the Research Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Humanities School of the Royal College of Art.34

Like the archaeologist, the methods of the historian are orderly and rigorously questioning. An extensive (if not comprehensive) range of primary evidence, whether documentary, literary, material or visual, as well as the methodologies and conclusions of past scholars are subjected to strenuous conceptual and empirical analysis. Social and cultural historians are interested in the particular and the unique, in the ordinary and the extraordinary, but their end is to understand the broad nature and working of past societies and how they have changed through time. This requires an imaginative and theoretical as well as an empirical approach and often utilises a wide range of analytical skills in order to deal with the many different types of source.35 Building on the important work carried out by the archaeological team in locating, categorising, describing, comparing and interpreting the findings in the cellar, a historian might want to understand more about the wider social, religious or political significance of these objects and what they might reveal more broadly about the workings of an early modern alehouse or tavern in London.

Smoking and drinking were by their nature international activities, necessitating trade and exchange across Europe and with the New World. Even beer, though mostly made at home by the 1660s, had originated in Germany. Brewed in large quantities and, unlike ale, suitable for longer-term storage and transportation, by the seventeenth century it had overtaken native ale as the typical drink.36 Contemporary debates over the relative benefits of English ales and Spanish or French wines were common and were seen to be important in the creation of social, political and national identities.37 However, the material and decorative features of the Rood Lane assemblage are overwhelmingly northern European in origin, while many of the medallions on the stone bottles linked the objects to the Netherlands. At the same time, comparing the decoration on the ‘rigaree-cut’ foot of our ‘Venice glass’ shard against similar examples in the V&A’s and Museum of London’s collections showed that it complied closely with Dutch decorative tastes and techniques.

Since England and the Dutch United Provinces were in opposing diplomatic camps for much of the century and were actually at war over trade from 1650–1652 and from 1665–1666, these close material connections might seem rather odd at first sight. But at the grass roots level, whatever their governors might say, many Dutch and English people shared common interests, including the military defence of Protestantism, expansive naval trade, urban entrepreneurialism and drinking.38 Both sides liked to accuse the other of being heavy drinkers but, at the popular level, neither had much time for the more moderate drinking Catholic states of France and Spain or even the tee-total Ottomans. Unlike French and Spanish wines, Dutch and Rhenish pots were unquestionably, sometimes expressly, Protestant.39

The diverse materiality of the finds among which our glass shard sits is also significant from a social historical perspective. Historians increasingly agree that no easy line can be drawn between the service, fare or clientele to be found in early modern alehouses and taverns, or even coffee houses.40 While the archaeological team at first hoped that the material nature of the assemblage might help to establish whether Rood Lane was an alehouse, tavern or inn, it soon became clear from the archaeological record that in the three very different London sites examined – the Rood Lane cellar, the Bear Inn and the Guildhall – the pottery and glass objects that could be pressed into service when drink was called for were remarkably similar. This evidence points towards a socially diverse range of people coming into the Rood Lane alehouse (or tavern), who could, if they chose, drink from locally made black-glazed earthenware poured from German stoneware bottles, or, if they preferred, could experience the style and frisson of sipping from an immensely delicate ‘Venice glass’ (Figure 27.5).

What might make someone choose to drink from such a delicate glass rather than a vessel of some other material? Was an individual’s choice of drinking vessel a signifier of social class or perhaps gender? Perhaps, for most people, the only opportunity to drink from such a glass would have been in a tavern or alehouse. Why did taverns or alehouses feel obliged to provide such expensive facilities to their customers? By considering the language or discourse surrounding the idea of ‘Venice glasses’ in a variety of documentary, literary and visual sources, as well as the general prevalence of their ownership in wider society, we can go some way towards locating them in early modern drinking practices and uncovering their social significance.

In literary sources ‘Venice glasses’ were always imagined as fashionable, luxurious and immensely fragile objects. In 1587, historian Raphael Holinshed believed it was a mark of the sinful luxuriousness of his times that the rich had come to prefer items that were difficult to maintain, such as Venice glasses, rather than sturdier vessels made of intrinsically valuable materials such as silver or pewter.41 The delicate qualities of the Venice glass lent itself to moral metaphors. Moralists often repeated the story of a gentlewoman, overwhelmed by a sense of her own sinfulness, who used a brittle Venice glass to test the possibility of her salvation. She threw it to the ground but it remained miraculously unbroken, a testament to the power of God’s forgiveness.42 The beauty and frailty of Venice glass (‘often broken in the washing’) was often referred to as a metaphor for the constant care needed to maintain a good reputation,43 while playwright Thomas Dekker famously remarked that women were like Venice glasses – ‘one knock and they were spoiled’.44

Although by no means as typical as silver or pewter vessels, records of ownership of glass, especially ‘Venice glasses’, can be found among the middling sorts of society, both men and women, in probate and other legal records from Kent and Middlesex. For example, in 1642, Kent widow Sarah Thompson, obviously a great lover of things ceramic and glass, owned 18 glass bottles, several ‘galley pots’ (delftware jars) and as many as 28 glasses, some of which may have been displayed on her several ‘court cupboards’.45 In 1658, Robert Wright, Esquire, had a ‘set’ of 18 ‘Venice glasses’ worth 18 shillings.46 Though socially elevated, glasses were nevertheless discussed as being accessible to a wider populace. Waterman and poet John Taylor in a jesting pamphlet referred to Venice glasses being broken in drunken affrays in taverns.47 In one printed play, tricksters who had taken a large sum of money from their mark look forward to enjoying the heights of luxurious drinking, declaring they will ‘quaff in venice glasses’.48 That such glasses were regarded as an essential item with which to impress strangers is perhaps indicated by their inclusion in the lists of goods explorers to the new world were advised to take with them. Captured ships were also recorded as having Venice glasses among their goods.49

What would such a delicate object be doing in the rough and tumble of the alehouse or tavern environment? Court records can sometimes reveal the material transactions taking place in the alehouses and taverns of London and elsewhere. Taverns and alehouses seem to have made even their most precious cups available to all their clientele, regardless of their social status, while people might choose to drink from a number of different kinds of vessels over the same evening. In December 1684, for example, James Fulham ‘after having had a Pot and a Glass, desired a Silver Cup’.50 Did the type of drink being consumed dictate such choices, or was the material and size of a vessel to be drunk from affected by the reason behind someone’s drinking – for example, because a special event was taking place and a ‘health’ or toast was to be drunk? The typical practice of sharing vessels in such cases meant that a larger vessel than normal was required, perhaps made of something more precious than earthenware or specially decorated.51 The boisterous nature of healthing might suggest that a ‘Venice glass’ would not be the ideal for such a practice, although tall glasses, decorated with measuring rings so that drinkers could share the contents equally, do seem to have been popular in the seventeenth century.52 Nevertheless, several writers commented that a ‘roaring’ young drinker, with pretentions to gentlemanly status, having chosen to ‘drink to his Venus in a Venice-glasse’ (presumably to embody her delicate beauty) would then throw it ‘over his head’ and break it to prevent any other health being drunk from the same glass – or any other man approaching his love.53

While it seems that alehouses and taverns provided beautiful objects for the use of their customers, the question of what such valuable objects were doing in the cellar remains. A funeral sermon by pastor Thomas Gataker, metaphorically discussing the vulnerability of the soul, pointed out that ‘a Venice glasse, as brittle as it is, yet if it be charily kept, if it be carefully set vp, if it stand shut vp vnder locke and key, out of vse, out of harmes way, it may hold out many ages, it might last peraduenture euen as long as the world it selfe is like to last’.54 Those who were recorded as possessing glasses did indeed tend to keep them ‘charily’ locked away from harm in special pieces of furniture. For some a simple closet sufficed, as for Kent innholder Robert Jackson, who kept six glasses there in 1607, and also for widow Mary Allen in 1638, Parson William Master in 1641 and gentleman John Boughton in 1666.55 But many more kept their glasses in a specially made, probably wall-hung, wooden, ‘glass case’.56 This was so for Kent tanner Nicholas Mitchell and also James Jackson (trade unknown) along with many others of their contemporaries, especially tailor Thomas Hunt, who kept his three ‘Venice glasses’ there in 1608.57 On the whole, then, we would have expected to find any glasses in Rood Lane upstairs in the main room, on display in a wall-hung ‘glass case’.

Nevertheless, the idea was posited earlier on that glasses may have been provided in the cellar because sometimes cellars were also used as drinking places. Two instances can be found of Venice glasses being kept in proximity to cellars; in 1609, John Maselate was recorded as keeping ‘6 venice glasses, 18 wine pots and 2 silver cups’ stored in the ‘room over the wine cellar’58 while in 1638, Lord Elphinstone’s castle was recorded as having a wine cellar in which seven glasses were kept.59 Although, even in a cellar, we might still expect glasswares to be kept safely in a cupboard or case of some kind, the wood of any such cupboard or case would not have survived for several hundred years to be found by even the most diligent archaeologists.

Finally, we should consider the possibility that the glasses in the Rood Lane cellar were already broken when the cellar wall tumbled down. This returns us to the question of why only shards (or sherds) of glass could be found in the Rood Lane cellar when so many of the other objects were recovered more or less in their entirety. Even if they had become broken in the course of a drinking bout, why keep broken glasses? Natural philosophers exploited the fragility of Venice glass more practically than literary or moralising authors, and it was thought to have a number of important qualities, of use in areas not connected to drinking. The recipe for authentic Venice glass was well known,60 although by the seventeenth century, much was in fact made in France, the Netherlands and even London (known to glass specialists today as façon de Venise). These glasses were not necessarily regarded as inferior, however. Though not undisputed, experiments had revealed that a ‘Venice glass’ would break if poisons were put into it. At least one case of murder had been solved through this method.61 Ground Venice glass was also recommended for medical uses – especially as a salve for wounds. Thus, revered for its medical properties, our glass shard, and the others like it, may have been kept in the cellar ready for a very different use from that of convivial drinking; it seems unlikely that the broken glasses in the cellar had been used to detect poisoning, but they might have been kept ready for selling on as an ingredient for medicines. As such, though still valuable commodities, the shards (or sherds) were perhaps not valuable enough to risk heading down to the cellar to fetch them as the fire loomed ever closer.

In considering our sherd – or shard – how far have our disciplinary approaches differed and how far have they converged? What have we achieved by working together? While we very much share interests in materiality, function, space, technology and trade, and the agency of objects, our two disciplines take a very different view on the study of assemblages and the meaning of context. Archaeologists have a very long view on history. Any one archaeological site in the city of London could recover evidence of anything close to 1900 years of occupation; and archaeologists draw on an exceptionally broad knowledge of the material world, both chronologically and geographically. The archaeological notion of the ‘assemblage’ – a group of artefacts recurring together in a particular time and place, situated in a particular context (in our case, a cellar fill) – remains central to the discipline. This is very different from historians, who tend to be more specific in their interests as to time and place and who might explore an assemblage such as Rood Lane’s either in part or as a whole, depending on the broader social and cultural questions they are asking about their particular period. The archaeologist uses documentary and secondary evidence but also makes great use of typologies and evolutionary sequences based on material types and forms to give context for a particular object or an assemblage of objects, but the historian might range very widely in terms of sources and ideas in order to understand the wider social and cultural sphere in which any assemblage might play a small but important part. Dealing with shorter periods of time, historians are less reliant on the evolutionary concept implied in sequences and typologies, not only looking at periods when several types might be operating at once but also asking questions about change and continuity in designs and tastes. In the end, we can certainly agree that combining our two approaches in research, teaching and writing has proved exceptionally fruitful, offering a wider imaginative scope to the archaeologist and a more specifically contextualised understanding of the material evidence for the historian.

Research for this chapter was supported by the joint ESRC/AHRC Sheffield University & V&A Project Intoxicants and Early Modernity. Figures 27.1–2 were produced by Judit Peresztegt (MOLA). Site photography was by Gemma Stevenson (Figure 27.3) and studio photography (Figure 27.4) by Andy Chopping (MOLA). Figure 27.6 was produced courtesy of Crab Tree Farm, Chicago.

1 Planning Policy Guidance 16: Archaeology and Planning 1990, Department for Communities and Local Government (now National Planning Policy Framework, 2012): http://www.cheltenham.gov.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=693) (accessed 02 2014).

2See N. Jeffries, R. Featherby and R. Wroe Brown, ‘ ‘Would I were an alehouse in London!’: A Finds Assemblage Sealed by the Great Fire of London from Rood Lane, City of London’, Post-Medieval Archaeology 48:2 (2014), 261–284.

3David Gaimster, German Stoneware (London, 1997).

4W. Davey and H. Walker, The Harlow Pottery Industries (London, 2009).

5D. Atkinson and A. Oswald, ‘London Clay Tobacco Pipes’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 32 (1969): 171–227.

6H. Willmott, Early Post-Medieval Vessel Glass in England c.1500–1670, Council for British Archaeology Research Report 132 (2002), 36–42.

7B. Richardson, ‘ ‘The Glass’ in Jeffries, Featherby and Wroe Brown, ‘Would I were an alehouse in London!’ ’, 269–271; 277–278.

8Angela McShane, ‘Material Culture and Political Drinking in Seventeenth-Century England’, in Phil Withington and Angela McShane eds., Cultures of Intoxication, Past and Present Special Supplement (May 2014): 247–276, 263.

9This object and the rest of the finds from this site will be curated under the sitecode FEU08 in the London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre (LAARC), 46 Eagle Wharf Road, London, N1 7ED and can be viewed by appointment.

10As defined in the latest edition of the journal Post-Medieval Archaeology (2014).

11D. Hicks, ‘Historical Archaeology in Britain’, in D. Pearsall ed., Encyclopaedia of Archaeology (Oxford, 2007): 1318–1327, 1324.

12C. Renfrew and P. Bahn, Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice, 2nd edn (London, 1996), 546.

13Ibid., 25; 108; 114–116.

14J. Schofield, The London Surveys of Ralph Tresswell (London, 1987), 28.

15J. Hunter, ‘English Inns, Taverns, Alehouses and Brandy Shops: The Legislative Framework, 1495–1797’, in Beat Kumin and B. Ann Tlusty eds., The World of the Tavern (Aldershot, 2002): 65–82.

16J. A. Chartres, ‘The Capital’s Provincial Eyes: London’s Inns in the Early Eighteenth Century’, London Journal 3:1 (1977): 24–39, 25–26, 29.

17Jeffries, Featherby and Wroe-Brown, ‘ ‘Would I were an alehouse in London!’ ’.

18Ibid.

19Gaimster, German Stoneware, cat. 68, 220 and cat. 67, 220.

20See N. Jeffries and N. Major, ‘Mid 17th- and 19th-Century English Wine Bottles with Seals in London’s Archaeological Collections’, Post-Medieval Archaeology 49:1 (2015) 131–155.

21H. Willmott, Early Post-Medieval Vessel Glass in England c.1500–1670, Council for British Archaeology Research Report, 132 (2002), 35–42.

22Richardson, ‘The Glass’.

23Willmott, Early Post-Medieval Vessel Glass, 16–17.

24Ibid., 2002, type 1.8, fig 12, 40. For excavated examples from the Netherlands see P. Bitter, Gertworteld in de bodem Archeologisch en historisch onderzoek van een pottenbakkerij bij de Wortelsteeg in Alkmaar, Publicaties over de Alkmaarse Monumentenzorg en Archaeologie I (Zwolle, 1995), cat. nos. 154–156, 160–162; H. Willmott, ‘Anglo-Dutch Drinking Glasses: Comparisons of Early 17th Century Material Culture’, The Journal of the Glass Association 6 (2001): 7–20.

25H. Willmott, A History of English Glassmaking ad43–1800 (Oxford, 2005), 70–76; 94–95.

26 http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O5133/wine-glass-de-lysle-anthony/

27 http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O5286/drinking-glass-sir-jerome-bowes/

28Schofield, The London Surveys of Ralph Tresswell, 26.

29D. Keene, ‘Patterns of Building’ in J. Schofield, P. Allen and C. Taylor, ‘Medieval Buildings and Property Development in the Area of Cheapside’, Trans London Middlesex Archaeol Soc 41 (1990), 186.

30S. Ruggles-Brise, Sealed Bottles (London, 1949), 20.

31Ibid., 28.

32R. Latham and W. Matthews eds., The Diary of Samuel Pepys, 11 Vols (Berkeley, 2000), IV: 4; see also 31 August 1660, I: 235.

33Arjun Appadurai ed., The Social Life of Things – Commodities in Cultural Perspective, 2nd edn (Cambridge, 1986, 2003); S. Lubar and W. David Kingery eds., History from Things. Essays on Material Culture (Washington, 1993); W. D. Kingery, Learning from Things: Method and Theory of Material Culture Studies (Washington, 1996); John Brewer and Roy Porter eds., Consumption and the World of Goods (New York, 1993); Richard Grassby, ‘Material Culture and Cultural History’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History 35:4 (2005): 591–603; Karen Harvey ed., History and Material Culture (New York, 2009); Tara Hamling and Catherine Richardson eds., Everyday Objects: Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture and its Meanings (Farnham, 2010).

34Bringing scholars from museums and universities into fruitful dialogue, this partnership has directly influenced (and been mutually influenced by) a significant number of social, cultural and economic historians working in the field, including John Styles, Giorgio Reillo, Carolyn Sargentson, Karen Harvey and Sara Pennell. Indeed, by way of preparation for this essay, the authors devised and jointly taught a short V&A/RCA History of Design MA course in Spring 2014 on the ‘Material Cultures of Intoxication’.

35Ludovica Jordonova, History in Practice (New York, 2000); Garthine Walker ed., Writing Early Modern History (London, 2005).

36J.M. Bennett, Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300–1600 (Oxford, 1996); Phil Withington, ‘Intoxicants and Society in Early Modern England’, The Historical Journal 54 (2011): 631–657.

37See McBride, Ludington and McShane et al in Adam Smyth ed., A Pleasing Sinne: Drink and Conviviality in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2005).

38S.C.A. Pincus, ‘From Butterboxes to Wooden Shoes: The Shift in English Popular Sentiment from Anti-Dutch to Anti-French in the 1670s’, Historical Journal 38:2 (1995): 333–361.

39Andrew Morrall, ‘Protestant Pots: Morality and Social Ritual in the Early Modern Home’, Journal of Design History (2002): 263–273.

40J.R. Brown, ‘The Landscape of Drink: Inns, Taverns, and Alehouses in Early Modern Southampton’ Unpublished PhD Thesis (University of Warwick, 2008); B. Cowan, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (New Haven, 2005).

41Raphael Holinshed, The first and second volumes of Chronicles (London, 1587), 167.

42R. Bolton, Instructions for a right comforting afflicted consciences (London, 1631), 5.

43H. Burton, Conflicts and comforts of conscience a treatise (London, 1628), 22–25.

44Thomas Dekker, A tragi-comedy: called, Match mee in London (London, 1631), 13.

45Transcribed in Mark Overton et al., Unpublished Transcriptions of Kent Records Office Probate Inventories 1600–1800 (1998): [1872 $11.9.193/ Sarah Thompson, Widow, Wye, Kent, 3.2.1642]

46John Cordy Jeaffreson ed., Middlesex County Records, Volume 3: 1625–67 (London, 1888), 275

47J. Taylor, A iuniper lecture With the description of all sorts of women, good, and bad (London, 1639), 214.

48L. Barry, Ram-Alley: or merrie-trickes A comedy diuers times here-to-fore acted (London, 1611), Sig. G1+1.

49Richard Hakluyt, The principal nauigations, voiages, traffiques and discoueries of the English nation made by sea or ouer-land, to the remote and farthest distant quarters of the earth, at any time within the compasse of these 1500. Yeeres, 3 Vols (London, 1598), 107.

50McShane, ‘Material Culture and Political Drinking’, 263.

51Ibid., 275.

52Willmott, ‘Anglo-Dutch Drinking Glasses’.

53Richard Brathwaite, The English gentleman containing sundry excellent rules or exquisite observations, tending to direction of every gentleman, of selecter ranke and qualitie; how to demeane or accommodate himselfe in the manage of publike or private affaires (London, 1630), 42; Frederick Hendrick van Hove, Oniropolus, or dreams interpreter … After which follows the praise of ale (London, 1680), 79.

54T. Gataker, Abrahams decease (London, 1627), 41.

55Transcribed in Mark Overton et al., Unpublished Transcriptions, 2104 $11.3.7, Mary Allen, Widow, Elham, Kent, 11.3.1638; 1921 $11.7.59 William Master, Parson, Rucking, Kent, 25.5.1640; 2223 $11.28.31/ John Boughton, Gent., Lenham, Kent, 20.3.1666.

56Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture, the British Tradition: A History of Early Furniture in the British Isles and New England (Woodbridge, 1979), 338–341.

57Transcribed in Mark Overton et al., Unpublished Transcriptions, 1898 $11.8.139/ James Jackson, Canterbury, Kent, 11.6.1641; 2072 $10.72.414/ Nicholas Mitchell, Tanner, Chartham, Kent, 19.11.1638; 3147 $10.41.82/ Thomas Hunt, Taylor, Milton, Kent, 1608.

58Ibid., 4007 $10.45.416/ John Maselate, Goodhurst, Kent, 9.5.1609.

59Historical Monuments Commission, Lord Alexander Elphinstone, 16 February 1638 at Elphinstone (Dunmore), 9th report & appendix, part 2 (1884), 194, no.57.

60Francis Bacon, Sylua syluarum: or A naturall historie In ten centuries (London, 1627), 199, para. 770.

61Anon., Murther, murther, or, A bloody relation how Anne Hamton dwelling in Westminster nigh London by poyson murthered her deare husband Sept. 1641 (London, 1641), 5.