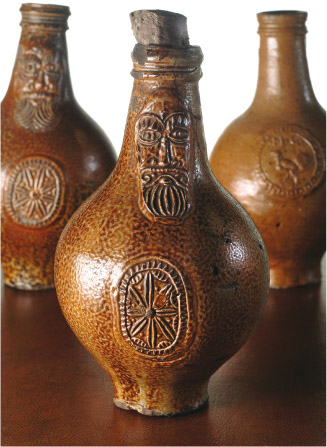

A bearded face grimaces threateningly from the speckled stoneware surface of a bottle. Aside from various external chips, this vessel and its cork are in relatively good condition – the engraved eyes and face of the bearded man, above the rosette medallion printed on the bulbous stomach, are still menacingly clear. Inside, the bottle holds 400-year-old contents: 11 bent pins and nails; a heart-shaped piece of fabric. The bottle was not originally designed to contain these items, yet the durability and ubiquity of this vessel type encouraged its appropriation for various purposes. One such purpose was as a cure for bewitchment in early modern England.

This vessel, imported from Frechen in Germany, was originally designed to hold drink. It was found in the St Paul’s Wharf area of the River Thames and is now in the Museum of London. In its material, form and decoration it is typical of hundreds of extant examples known as ‘Bartmann’ or ‘Bellarmine’ jugs and bottles, all with the distinctive stamped face of a bearded man. Its contents, however, single this object out as a rare example of what scholars have typically described as a ‘witch-bottle’, characterised as a superstitious ritual and folkish charm, a facet of popular magic.

However, a close analysis of this strange object, its accompanying practice and contemporary literature reveals that this bottle was not simply an apotropaic or prophylactic tool of the ignorant used merely to ‘ward off’ witches but was a scientifically and medically grounded cure for the specific disease of bewitchment. This remedy would act to alleviate the patient’s disease whilst also causing great pain and even death to the witch who had inflicted it. The contents of a bottle such as this would have varied but commonly included urine, pins, nails, cloth hearts, human hair or fingernail parings. These ingredients would have been added to this vessel before being heated or buried into the walls or floors of a house or grounds in order to activate the cure.

Three main factors demonstrate the function of such bottles in this curative procedure. Firstly, through examining the primary literature both materially and contextually, it is evident that the texts that discuss the cure were situated amongst elite, intellectual and scientific systems of knowledge, read by a range of people across wide social and spatial geographies, and owned and considered by an educated readership (Blagrave 1671; Glanvill 1681). Secondly, the bottles used for this cure – such as this vessel from central London – have been found across the country, not only in rural dwellings of the less-educated lower orders but also in larger houses of the wealthy and in educated urban centres. Finally, a material examination of the bottle and its contents reveals the incredible equivalence between this cure for bewitchment, and other contemporaneous scientifically and medically grounded remedies.

The material characteristics of these bottles have often been overlooked in accounts of their function as witch-bottles. Yet the physical attributes of this vessel demonstrate much about the cure for which it was used. The cork, bottle, and the formidable anthropomorphic mask imprinted upon it were key components in the curative process, which worked through ‘sympathetic links’. The notion that the universe was a network of correspondences was a recognised idea in the early modern world, promoted by Paracelsus, one of the most influential medical scientists of early modern Europe. According to this theory, advocated by the Royal Society, all beings were bound together by sympathetic links, so that any action brought about in the virtue or spirit of one would affect others. Thus the shape of the bottle – resembling a human bladder – held significant power in harming the bladder of the witch: when this vessel was filled with pins and heated or buried, the witch would feel corresponding pain.

Blagrave, Joseph (1671) Blagrave’s Astrological Practice of Physick, Discovering the True Way to Cure all Kinds of Diseases and Infirmities which are Naturally incident to the body of man. Being performed by such herbs and plants which grown within our own nation, directing the way to Distil and Extract their Vertues and making up of Medicines. Also a Discovery of some notable Phylosophical Secret worthy our Knowledge, relating to a Discovery of all kinds of evils, whether Natural, or such which come from Sorcery or Witchcraft, or by being possessed of an evil spirit: directing how to call forth the said Evil Spirit out of any one which is Possessed with sundry Examples thereof (London).

Glanvill, Joseph (1681) Saducismus Triumphatus: Or, Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions. In Two Parts, the First Treating of Their Possibility, the Second of Their Real Existence […] (London).