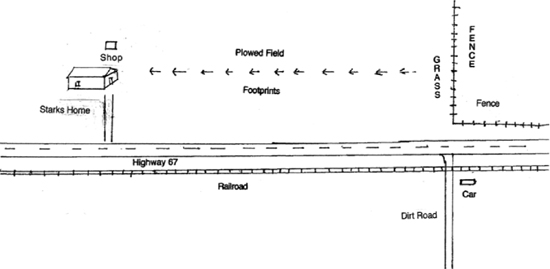

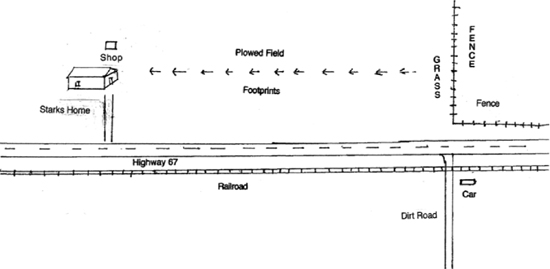

As Lt. Miller of the Arkansas State Police worked in and around the house the following morning, Chief Deputy Sheriff Tillman Johnson began about two hundred yards away, near where the suspect car had been parked the night before.

A fence almost directly across the highway from where the car had been parked divided Starks’s land from his neighbor’s. It was about a thousand feet from the fence to the house. Johnson strode across to the fence line. A portion of Starks’s land had been plowed, then dampened by rain, about a third of an inch the previous day. Johnson checked the plowed ground from the edges, looking for any sign. Along the fence row a long, narrow strip of grass provided a firm buffer between the fence and the plowed land.

He walked on the grass while studying the plowed ground. About a hundred feet from the highway, he found what he was looking for—footprints crossing the plowed field, in the direction of the house. He felt sure he’d found the killer’s route. He’d come directly from across the highway where Tackett and Boyd had seen the parked car. The man had taken that route so as not to be seen from the highway.

Recent plowing, along with the rain, had left the soil soft and in rows. Johnson stepped carefully alongside the tracks, following them without going close. None of the prints was ideal, though one was better than the others. It would be difficult to match, but he thought it possibly was a boot print with the heel worn on one side. He couldn’t be sure. The condition of the soil precluded making a precise model.

He followed the tracks across the field. They ran in only one direction, toward the house and outbuildings. Johnson, calm and cool in most situations, suddenly grew excited. These were definitely a man’s footsteps. He felt certain it was the killer’s path.

It appeared the stalker had risked the softer soil of the plowed ground in order to avoid being seen by a passing car on the highway. He had first headed straight for the house. This would have taken him near or into the welding shop where Starks frequently worked.

The gunman had a flashlight, which would have facilitated inspection of the shop. Although there had been some rain earlier, the plowed ground wasn’t boggy, though definitely softer than the grassy strip. Johnson, six-foot-one and weighing almost two hundred pounds and wearing cowboy boots, didn’t bog down at all but walked easily across the plowed field. Once he’d crossed the field, the killer could have wiped the mud off his shoes by dragging his feet over the yard and continued on his way.

After entering the grass of the yard, the tracks couldn’t be traced farther. Finding no tracks around the house, Johnson looked for tracks leading back to where the car had been parked. None crossed the plowed field in the returning direction. Apparently the killer had fled over the yard and crossed the highway and the railroad track to reach his car.

As for the strip of linoleum with a bloody shoe print sent to the FBI lab, no identification ever resulted. Johnson, for one, was never convinced that it was the killer’s footprint. Too many men were milling around inside and outside the house that night. Almost any of them could have left the print. But those across the plowed field, imperfect as they were, had to belong to the killer, Johnson reasoned.

The tracks were distorted. Mud further blurred the evidence. Two plaster casts were made of the imperfect tracks. One track looked like a walking boot with a heel worn off on one side. But they couldn’t take the cast and make a positive. It would be difficult to prove that a given boot or shoe had made it. The ground was too soggy. Only one thing was certain: the killer had muddy or damp footwear, whether he had washed them off or discarded them.

“You just couldn’t get a good plain track out of it,” said Johnson. “Mine looked the same, going along beside it. But it did put us into the idea that the man in that car had walked down to the house. We couldn’t track him anywhere else.

“We found some tracks leading from the house, but whose they were, we couldn’t determine. We couldn’t know they were the same person’s.

“It appeared that he would have gone across the railroad tracks and then gone back to his car. There was a lot of grass and water and it was wet through there and you just couldn’t tell much about it.”

Officers found several cigarette butts near where the suspicious car had been parked, indicating that, if the butts had been left there by the killer, he—or they, if anyone had been with him—had smoked them while waiting to ease across the highway. He may have arrived before it was fully dark and waited till darkness so that he could explore with impunity. There was also the possibility that someone dealing with a bootlegger had smoked the cigarettes, but it was another suggestive clue and, if true, indicated that the Starks home invasion was a premeditated, carefully calculated crime, whatever may have been the major motive for this or any of the other murders.

An approximate layout of the murder scene followed this rough map.

Howard Giles, son of Arkansas-side Police Chief R. Marlin Giles, served with the Navy in Washington, D.C., as a fingerprint specialist. At war’s end, he was assigned to Europe to help identify German Storm Troopers, using fingerprint records. He was there for about six months before discharge, after which he joined Texarkana’s Arkansas-side police department. Just after the Booker-Martin murders, he took over from Bryan Westerfield, who had filled in during the war. As it happened, he was in place when the Starks murder occurred and was sent out that night to collect any fingerprints he could.

On Monday after the shootings, with Katie still in the hospital in serious but improved condition, more than five hundred persons attended solemn funeral services for Virgil at the First Methodist Church, Arkansas. More than sixty of the mourners were relatives of the couple. The Reverend Edward W. Harris, who earlier had railed against the “criminal element” in Texarkana, conducted the services.

“This tragedy is the third of its kind that has struck our community,” the pastor said. “Each of us in a community way more than in the usual manner feel a sense of kinship with you in the sorrow you feel today,” he said to Mr. and Mrs. Jack Starks, parents of Virgil Starks. “It is a sorrow that weighs upon every home in this community.”

He expressed, for the family, confidence in officers and newspaper people, and all others “who bear the responsibility in the community for ending the reign of terror.”

Somber faces in the audience at times were streaked with tears.

On Tuesday morning, Sheriff Davis had a long talk with Katie Starks in her hospital room. She was in reasonably good spirits, considering what she had been through. She told the sheriff again that she hadn’t seen the man who shot her. She said she had started to get a pistol, but her vision had been so obscured by blood that she couldn’t be sure where she was going. By then she felt she was going to be killed. She wanted to leave a note before she died. But instead she decided to flee as she heard the intruder rip the screen from the back window, whereupon she flung caution to the winds and ran out of the house as fast as she could.

The Arkansas State Police’s forensics lab in Little Rock confirmed that the .22 caliber gun that killed Virgil Starks was an automatic or semi-automatic weapon. But the bullets were in too rough a condition for them to concretely determine if they came from a rifle or pistol, as the men who collected the bullets initially feared. If the bullets indeed came from a rifle, it was a common weapon that almost every family in the county owned.

It possibly was of foreign make, the ballistics expert said, but in his opinion it was a .22 Colt Woodsman. The weapon in the other four murders had also been a Colt, but a .32 caliber. “I think this is what you’re looking for.” It resulted in a search for the death gun by locating and firing hundreds, starting in the Homan community. Only if the gun itself was found could a definite identification be made.

Dr. C. L. Winchester, a veterinarian serving as coroner, an elected position, signed Virgil Starks’s death certificate. The stated cause of death was no more revealing than it had been in the deaths on the Texas side.

“Gun in hands of unknown person.”

Suspects were in short supply. As in the earlier murders, a clear motive was elusive. Starks’s reputation in the community was solid.

Weeks later, the FBI lab returned the killer’s flashlight to the Miller County sheriff’s department. The technicians hadn’t been able to find prints on the flashlight or its batteries. It was a heartbreaking report. It did, however, mean that they were dealing with an experienced criminal who had wiped off fingerprints or used gloves, an organized killer who had arrived at the crime scene determined to leave no clues.

The color and design of the flashlight was fairly uncommon, to the point that one like it could be identified, a two-celled flashlight with the tip of it red. Tillman Johnson checked every store in Texarkana. Only one store carried the brand, and the storekeeper didn’t remember selling that particular one. Johnson took the flashlight to J. Q. Mahaffey at the Gazette and asked if he would run a picture of the flashlight on page one. Mahaffey went to the publisher and owner, Clyde E. Palmer, who agreed to do so.

The Gazette also agreed to send a photograph of it, in color, over the Associated Press wire. The incident remained fixed in city editor Sutton’s memory for years afterward.

“The Gazette ran the first spot color photograph in the United States, of the flashlight left at the Starks home,” Sutton said. “Editor & Publisher magazine credited us with having been the first to do it. It was not a true color picture. We used two cuts, one of the shiny part of the flashlight, and one of the red handle.”

The Gazette ran a four-column photo ran on page one.

THIS IS A PICTURE IN DETAIL OF THE FLASHLIGHT FOUND AT THE SCENE OF THE STARKS MURDER. THIS IS A TWO-CELL, ALL METAL FLASHLIGHT, BOTH ENDS OF WHICH ARE PAINTED RED. THREE RIVETS HOLD THE HEAD OF THE FLASHLIGHT TO THE BODY OF THE LIGHT. THERE HAS BEEN ONLY A LIMITED NUMBER OF THESE LIGHTS SOLD IN THIS AREA. IF YOU HAVE OWNED OR KNOW OF ANY ONE WHO OWNED ONE OF THESE LIGHTS, REPORT AT ONCE TO SHERIFF W. E. DAVIS, MILLER COUNTY COURTHOUSE, TEXARKANA, ARK. YOU MAY BE THE ONE TO AID IN SOLVING THE PHANTOM SLAYINGS.

Nothing came of it.

The killing of Virgil Starks gave the case a new level of urgency. The Starks case increased the tension that the murderer still had not been caught, and brought in political figures. Congressman Wright Patman, a powerful U.S. representative who lived in Texarkana, Texas, made contact with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Attorney General Tom Clark, securing promises that priority would be given to the Texarkana needs.

The governor’s office in Little Rock beefed up the State Patrol contingent in the Texarkana area, assigning ten troopers to Miller County.

On the Texas side, Ranger Gonzaullas announced the arrival of a powerful mobile radio transmitting station—“one of the best in the country.” Ten more Texas DPS patrol cars, each with two men in it, arrived, equipped with three-way radio sets. Within the week, a Teletype machine in the sheriff’s office connected Texarkana with major law-enforcement offices all over Texas.

Texarkana had gained, albeit by dubious means, what very rarely happened—focused attention from both state governments, no longer a stepchild of two states.

The Texas crimes had already spread caution across the state line, especially after dark. On the night of May 3, Leslie Greer, campaigning for Miller County tax assessor, and his wife attended a fish fry and foxhunt in the rural southern part of the county. When two youths rode up on horses, the group went on alert. Alice Greer fetched her husband’s antique .45 revolver from the car, readying it for action. The young horsemen turned out to be harmless local residents, but the culture of fear only continued to grow with the latest murder.

“Regular” crime continued at a lesser pace. On Sunday night, May 5, two days after the Starks shooting, a 1941 Chevrolet coach was abandoned in the 300 block of West Broad, near downtown. It bore Louisiana license plates. It remained there for several days before police towed it to the station. Its owner was Joe Morgan of Shreveport. He was notified and went to Texarkana to retrieve his property. He said it had been stolen from him on Saturday, May 4. Phantom fears had slowed other crimes but hadn’t halted car theft, a seemingly endemic practice.

Rumors surfaced in the Starks case as they had in the earlier murders, threatening to dominate the investigation. Many of them assumed that a different criminal had perpetrated the latest one. Similar rumors had afflicted the Hollis-Larey beatings, even the Griffin-Moore murders, that a jealous suitor was to blame. That they were all unproved hardly slowed them. In the Starks case, rumors eventually embraced almost every variant possibility, without a shred of basis. An angry man wreaking vengeance on Virgil Starks hardly would have stopped shooting after firing only two shots that obviously had killed him. In so-called crimes of passion, the anger is so open, so volatile that the killer may confront his victim in broad daylight and shoot and shoot and shoot, usually until he is out of bullets. He also would have shot and run. No evidence was ever presented to prove any of the rumors. The loose talk also unjustly assailed the integrity of the victims.

Several distinctive features of the Starks case argued for its being a continuation of the earlier serial killings in Texas, rather than a grudge slaying or a crime of passion.

One of the case’s strangest aspects feeds into the argument. Despite the widespread terror over the region, Starks sat in a chair by a window with the shade up, at night with the light on inside, dark outside. Anyone could see inside; he couldn’t see outside. Clearly Starks displayed no fear of the “Phantom” or anyone else. He obviously lived in less fear of the serial killer on the Texas side than did all of the others in his community. He might well have been the only one in the region so vulnerable.

Tillman Johnson believed Starks might have felt protected by virtue of his house being close to a relatively busy major highway, the main route from Texarkana to Little Rock, too public for the killer to risk. And, of course, it was in Arkansas, not Texas—a fact that failed to calm most Arkansans that fateful night.

The light could be easily seen from the highway. For an impulsive, or compulsive, killer the temptation may have been more than he could resist. The Phantom, by then, whatever his level of intelligence, realized lovers’ lanes were more dangerous for him now, as they were now full of disguised officers setting traps in an area already teeming with lawmen.

Going by the tracks that Johnson had found, the killer appeared to have gone first to the welding shop, perhaps seeking a piece of equipment he could steal and sell. A thief would have done that. This also would have coincided with the noise Katie had heard outside. A man intent solely on assassination wouldn’t have bothered to check out a welding shop before hurrying to settle a score.

That said, the man may have intended to steal or rob, but he also came to kill. If he had not, he wouldn’t have been armed. He saw Virgil Starks’s light from the highway. He parked away from the house. He got out of the car with his .22 and flashlight. The flashlight indicated that he needed it to look around, in the shop or anywhere else, for items to steal. The gun suggested a more violent intention. If theft had been his only goal, he wouldn’t have needed a gun.

The killer must not have lived in the community or known much about it. He seemed unaware that the Starkses had a telephone—until Katie ran to the phone to call. A gunman with murder in mind, and thinking clearly, would have cut the phone line—if he’d known there was one. This argues for the view that a stranger did it. Rural telephones were so rare at that time that everyone in the rural community would have known who had one.

If he’d known of the phone but for some reason neglected to disable it, he arguably would have shot Katie as she came within range while near Virgil’s body. His first action did not come until she turned from the body and lifted the receiver and started to crank the mechanism to reach an operator. Then he shot her and broke into the house to finish her off. He may have gloated at her horror upon finding her husband dead, then panicked when he saw how fast the alarm could be spread and expedite his capture. If he could not kill the witness, he must escape, as soon as possible.

Had he killed Katie, no one would have known until the next day, much as had happened in the two Texas double murders. Based on this, his target was not only Virgil Starks but everyone else in the house. He would have had time to see her, watch her, then go inside and kill her up close at his leisure, much as he had done to his earlier victims. The phone, suddenly entering his perception, thwarted him. What may have seemed to be an easy mark at an isolated rural home became a dangerous boomerang. He didn’t have time to search for valuables, even to take Starks’s wallet or money.

Furthermore, if the killer had been someone known to the Starkses, with a grudge against Virgil, he likely wouldn’t have lingered to see Katie and possibly be recognized. If he didn’t know them, he’d have less fear of recognition—he was a stranger, after all, and one who intended to leave no witnesses.

After she fled, he didn’t know where she was or where she’d gone. He ran to his car. His actions indicated that he wasn’t familiar with the locale. If he’d known the Starkses and the community, he would have known where the other houses were and where she might have gone. But he was in the dark, in more ways than one—he’d also lost his flashlight.

Might it have been a “copycat” killing, a term that did not arise for decades? Unlikely, for the killer would run even greater risks, if he had a known motive. He then might be charged with the Texas slayings also.

As was to be emphasized later by Max Tackett, each of the Texas victims had been shot two times, as if the killer believed no more was needed to wipe out a life. Paul Martin had been shot four times but only twice at a time, the fatal series coming only when the killer, afterward, apparently saw that the boy was still alive from the earlier two shots. In Arkansas, the gunman had shot Starks two times, then Katie twice. He could have shot either more times but had not. A similar mentality seemed behind all of the crimes.

A parallel to the Griffin-Moore murders was that Starks also was shot almost point-blank in the back of the head, execution-style. The killer seemed to know it was the surest way to kill, not a difficult conclusion to reach but one that suggested knowledge gained through experience.

If the earlier murders were crimes of opportunity, the Starks shootings could be seen as continuing the pattern. The Starks home provided the easiest target he’d had. Similarities that appeared to link the cases were several: couples only as victims, killing or disabling the male first, two shots at each victim (except for Martin, killed in two series of two shots each), an automatic weapon, vulnerable victims at night, use of a flashlight in at least two, possibly all, cases.

A strong flashlight was a part of the gunman’s equipment in at least two of the cases, the Hollis-Larey beatings and the Starks shootings.

Though the caliber was different in the Starks case with a different gun, an automatic was used in the two double murders and probably in the beatings. The same .32 automatic killed four victims, a .22 automatic rifle or pistol in the Starks case. Knowing that the police were looking for a .32 automatic warned him to dispose of it, while a .22 rifle or pistol wasn’t suspicious—until May 3.

Arguments seeking to derail the one-killer theory pointed out that a different weapon was used in the Starks slaying, that the victims were at home in a house and not in a secluded lovers’ lane, and that the victims were older. But the argument only deflects, rather than refutes, the position that the same man did it all. The distinctions were superficial. He obviously would change his weapon to a more common, less conspicuous caliber. By then, he had a more restricted cast of potential victims from which to choose. Where else but in a home could the killer find a couple at this point, now that all the lovers’ lanes were being watched? Thousands locked their homes tight and shielded their windows after nightfall. Lovers’ lanes were too hot to explore. He had to hunt his game in a safer venue.

Additionally, the Starks killer appeared to be an experienced burglar, suggesting that he had committed a range of other crimes in the past, perhaps as a career criminal. He broke into the house as surely and swiftly as an old hand. He hadn’t needed that skill in the previous crimes. He also seemed to know the rural roads on the Texas side better than in the Homan community, suggesting that he had moved from his accustomed base of operations in Bowie County to a less familiar rural Miller County.

If the killer was a different one, settling a grudge against Starks, why did he linger just outside the window after he had shot Starks dead until Katie entered the room—to eliminate a witness? She had not witnessed the shooting. The shooter had not seen her until she entered the room. He could have shot and run and escaped before she appeared. What had he waited for, to see what she looked like? A grudge-holder would have known both Starks and his wife and what she looked like.

Did he shoot her to keep her from telephoning to spread the alarm? Undoubtedly. But if he had been a man who lived in the community he would have known the Starkses had one of the few rural telephones. He could have cut the phone line before he fired. The fact that he did not argues for his not knowing about the phone or knowing the couple. Everyone in the community knew of the telephone. A rank stranger would not have.

Officers never developed any evidence to implicate anyone who knew Starks. They thoroughly checked out every suspect. The Starks shootings were as motiveless as the earlier ones.

In the final analysis, a logical marshalling of the facts gave greater credence, and a preponderance of evidence, to the same hand’s having committed all four incidents.

The Texas Phantom, whoever he might be, in all likelihood also was the Arkansas assassin.

Vexing times took different forms over the nation. In Georgia the Ku Klux Klan—“for white gentiles only”—burned five crosses on top of Stone Mountain as white-robed, masked Klansmen made their first public statement since Pearl Harbor. The Associated Press reported that seven hundred Klansmen initiated five hundred new members into the secret organization, with a thousand wives and children of the new members brought in by five chartered buses. The Georgia group was described as the “mother Klan” of all American KKK organizations.

The week after the Starks shootings, another body turned up, near Ogden, Arkansas, about sixteen miles north of Texarkana in adjoining Little River County. The body was mutilated, having been run over by a Kansas City Southern train. A Social Security card identified him as Earl Cliff McSpadden; an employment card gave Shreveport, Louisiana, as his home. His brother in Dallas identified him as a transient oil-storage-tank builder. The family had not heard from him since May 3. His letter of that date bore a Texarkana postmark.

The question immediately rose in lawmen’s and residents’ minds: Was he murdered and his body set on the train track to cover up the crime, or had he been struck by the train and killed instantly? Opinions differed. The coroner, Dr. Frank G. Engler, empaneled a jury that returned a verdict coinciding with his own conclusion that McSpadden had died “at the hands of persons unknown.” Dr. Engler believed McSpadden had been stabbed to death elsewhere and his body placed on the tracks to conceal the crime and perhaps make it look like an accident or suicide. The coroner said that although the body had been mangled, there were no bruises indicating that the man had fallen from a train. He cited a deep wound two inches long on the left temple, deep enough to have caused death, and cuts on the hands indicating the dead man had struggled with an assailant armed with a knife. He said McSpadden had been dead for at least two hours before the body was placed on the tracks, that there wasn’t enough blood around the wounds that caused the death when the body was found. The left arm and leg had been severed. A freight train had passed the Ogden station at five-thirty that morning. Blood was discovered on the highway a short distance from where the body was found early that morning.

Little River County Sheriff Jim Sanderson strongly disagreed. He felt sure that the train had killed him without help from anyone else. He believed the death was accidental. He felt “absolutely certain” of it and considered the matter closed.

By then, any suspicious death in Texarkana was likely to gain widespread attention, fueling the rumor mill with a new frenzy of speculation. Few believed this death was connected with the earlier murders, though. It simply did not fit the profile.

Forty-seven officers, most of them special deputies, patrolled secluded lanes. None would be quoted, but the Gazette reported that “general sentiment of the majority [is] that the motive for the murder was one of sex mania.”

An unnamed officer said, “I believe that a sex pervert is responsible.” Off the record, one said he thought that in the first murders Griffin’s pockets had been turned inside out in an effort to conceal the real motive.

In most minds, sexual assault, despite evidence to the contrary, was accepted as the chief motive. The news article built upon that existing belief.

“A diabolical killer,” the story began, “believed to be a sex maniac, who blasted the peace of a modest farm home into a nightmare of blood and horror Friday night, remained at large Saturday night and it was feared he might strike again at any moment, at any place, at anyone.”

On Sunday after the murder, three weeks since Betty Jo Booker and Paul Martin were shot to death, an eight-column, inch-high, all-capitals headline on page one of the Gazette proclaimed:

A three-column picture of Katie Starks in her hospital bed, her head swathed in so much bandaging that she was unrecognizable, commanded a portion of the front page under the headline.

The prison riot at Alcatraz, tagged as “the most spectacular in the history of federal prisons,” which had ended in the deaths of the convict ringleaders and two guards, with fourteen wounded, remained on page one but was swept from the main headline into a one-column story.

The Texarkana headline verified the suspicions and anxieties of thousands. Panic knew no bounds.

What type of man was responsible? The unknown factors promoted his mystique, making kings of rumors. The Gazette began looking for an expert who might offer insight. Two days after the Starks shooting, staffers found their man—Dr. Anthony Lapalla, a psychiatrist at the Texarkana Federal Correctional Institution.

Dr. Lapalla offered meager solace to a populace already up to their necks in fear. He predicted that the murderer was planning “something as unexpected as was the murder Friday night of Virgil Starks and the attempted murder of Mrs. Starks.” He believed the same man had committed all of the crimes. “He may lay low for awhile, but eventually he probably will commit another crime.”

He pegged the man to be about middle age, with a strong sex drive, a sadist. Such persons—intelligent, clever, and shrewd—Dr. Lapalla said, often are not apprehended.

Dr. Lapalla’s theory held that the murderer knew at all times what was going on in the investigation and realized the outlying roads were being constantly patrolled. That would explain why he had struck the Starkses in their home instead of waylaying persons on the roads.

Basing his theory on case histories of similar criminals, he noted that such criminals often divert attention to a distant community, causing people to believe the crimes are unrelated, or else he may overcome his desire to kill and assault women.

Dr. Lapalla doubted the man had ever been confined in a mental institution. He also doubted he was a war veteran because such “maniacal tendencies” would have been observed while in the service. The killer wasn’t necessarily a resident of the area, despite how well he seemed to know it. He could have come from another community but acquainted himself with the local situation before beginning his killing spree.

“This man is extremely dangerous, with a tremendous impulse to destroy,” Dr. Lapalla emphasized. “He works alone, and no one knows what he is doing because he tells no one. He might be thought of as a good citizen. He probably has reasoned that the only way to remain unidentified is to kill all persons at the scene of his crime.”

Although several black men had been picked up by then, Dr. Lapalla felt certain a white man was to blame.

With the unknown factor gnawing insidiously at every mind, Dr. Lapalla’s insights soothed few nerves and only brought into the open old hidden fears. The Phantom could be anyone! Residents wondered about the man across the street, the respected businessman, the minister’s son, or some returning veteran perversely reacting to his combat trauma.

Satisfied that the February beatings had been the early work of the same man who had attacked and killed other couples, J. Q. Mahaffey dispatched a reporter to Frederick, Oklahoma, to interview Mary Jeanne Larey, the young woman beaten in February. The editor contracted with Paul A. Burns, a printer, entrepreneur, and pilot, to fly Lucille Holland there. Burns’s 65-horsepower, two-place side-by-side Luscombe Silvaire had a three-hour range and he expected to reach Frederick, Oklahoma, before dark. A stout headwind, however, slowed the plane significantly. He had to stop once to refuel, then land at Frederick in the dark after buzzing the field to bring the airport manager out to train car headlights on the field.

The teenaged Mary Jeanne insisted that the February 22 attack on her and Jimmy Hollis was the first in the series of crimes committed by the Phantom. She was sure of it beyond any doubt. She still did not understand why officers didn’t believe her when she told them the man was black, an assessment with which Hollis had disagreed. But, she added, Texas Ranger Joe Thompson had flown to Frederick after the Martin-Booker murders and questioned her again.

“I believe now that the officers connect all of the crimes,” she said.

She was trying to lead a normal life, but for the first time in her life, her aunt said, Mary Jeanne was “extremely nervous” and would neither sleep in a room alone nor go upstairs by herself. “And in her dreams,” wrote Holland, “Mary Jeanne sees her attacker almost every night.”

The following morning, Holland’s story dominated the front page.

A week after the Starks shootings, the traffic death toll remained stuck at fifteen. None had died from traffic in May, with thirty-one days since the last death. A total of fifty-six had been injured for the year, three in May. Gunshots had claimed more lives than traffic accidents over the past two months, a dramatic turnabout. The Phantom, competing with thousands of motorists, seemed to be winning the death game, hands down.

A current movie title featuring Richard Arlen reflected the rising tensions, titled The Phantom Speaks.