MATERIALS AND METHODS

HABITATS AND COLLECTING LOCALITIES

Most of the surveying took place in the expansive and diverse Santa Cruz Department. Primary collecting localities are listed here with their coordinates and elevations and depicted on the map below (Figure 1) by the associated numbers (note that “a” and “b” are used for the same number when the specific localities are so close to one another that they would not show up on the map as distinct). There is a relatively large cluster of localities in west-central Santa Cruz Department around Amboró National Park. This region has been the most productive, providing over 90% of the Bolivian species of longhorned beetles:

FIGURE 1. Map of Bolivia showing primary survey localities, numbered as described in text.

1. Santa Cruz Botanical Garden, Andrés Ibáñez Province, 17°47’S, 63°04’W (375 m)

2. Potrerillo del Guenda Reserve, Andrés Ibáñez Province, 17°40’S, 63°27’W (370 m; Figure 2c)

3. Flora and Fauna Hotel, Ichilo Province, 4–6 km south-southeast of Buena Vista, 17°30’S, 63°38’W (400 m; Figure 2d)

4. Concepción vicinity, Ñuflo de Chávez Province, 16°08’S, 62°01’W (380 m)

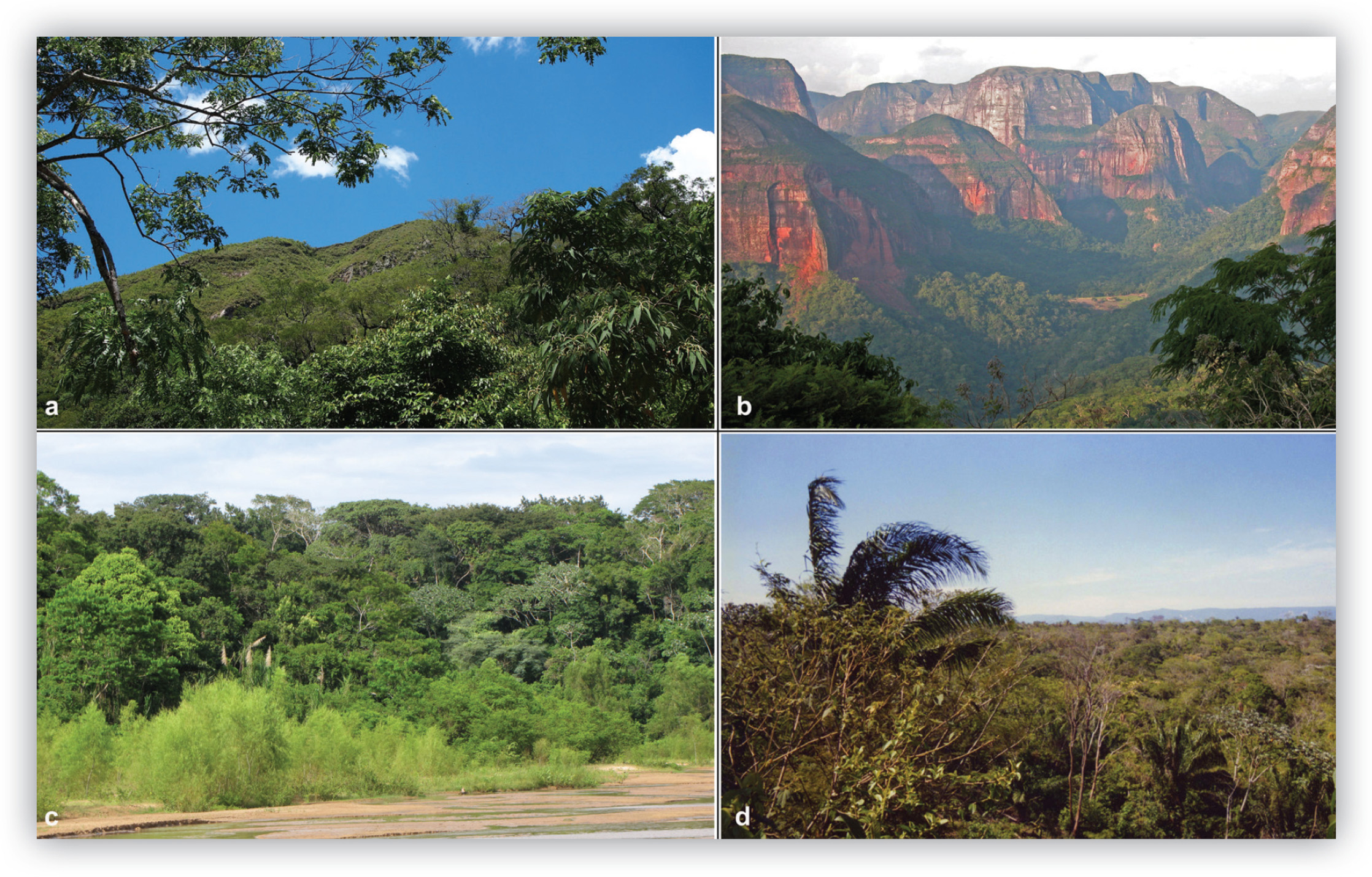

5a. Cuevas vicinity, Florida Province, 18°12’S, 63°41’W (1,310 m; Figure 2a)

5b. Refugio Los Volcanes Reserve, Florida Province, 18°06’S, 63°36’W (1,000–1,200 m; Figure 2b)

6a. Achira Sierra Resort, Florida Province, 18°09’S, 63°49’W (1,350 m)

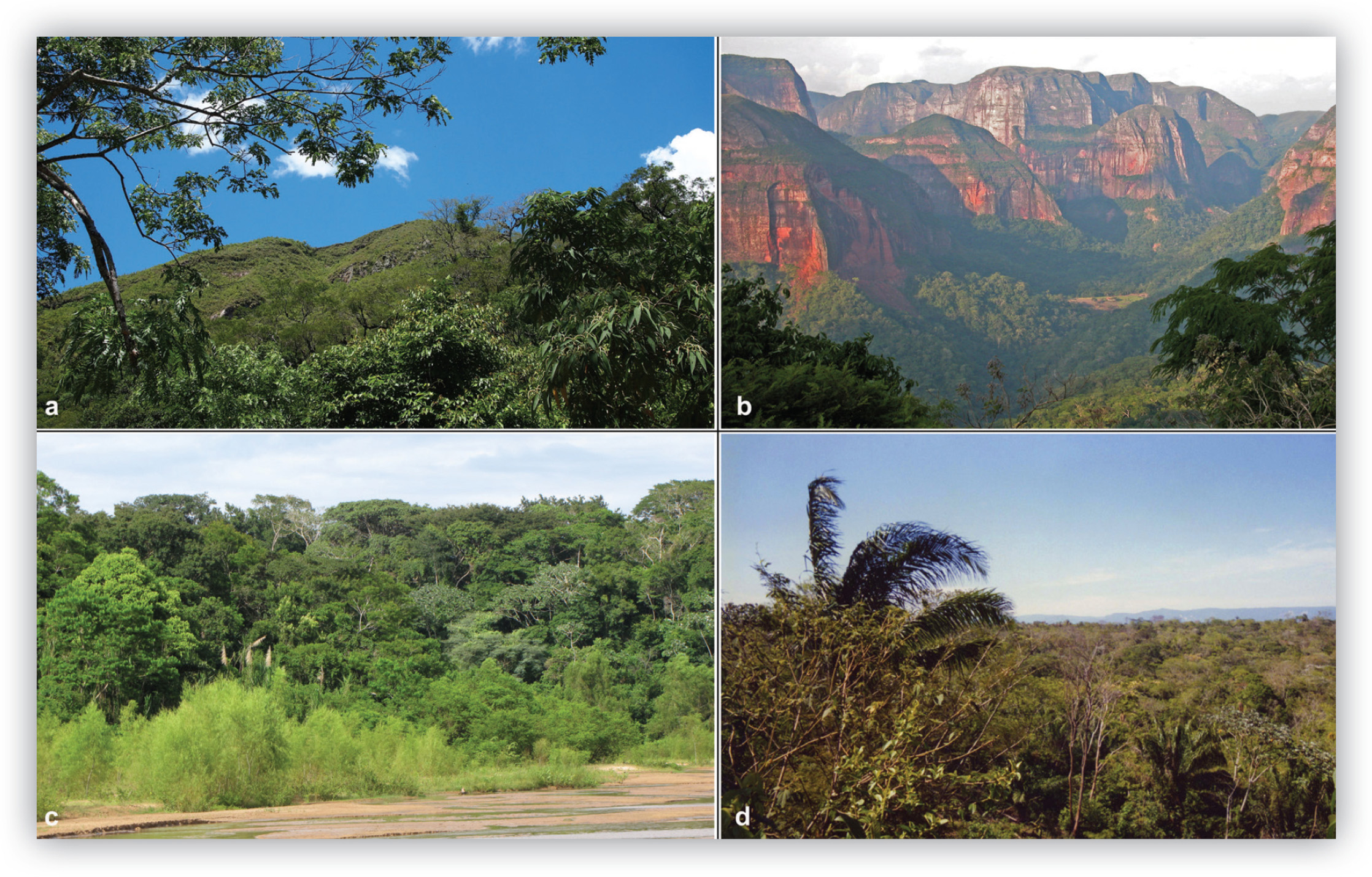

6b. Vicoquin area, road to Amboró above Achira, Florida Province, 18°07’S, 63°47’W (1,700–2,000 m; Figure 3c)

7. Samaipata and vicinity, Florida Province, 18°09’S, 63°52’W (1,620 m; Figure 3b)

8. Pampagrande and vicinity, Florida Province, 18°06’S, 64°15’W (1,700 m; Figure 3a)

9. Comarapa and vicinity, Manuel Maria Caballero Province, 17°58’S, 64°29’W (1,725 m)

10. Camiri vicinity (22 km northeast), road to Eyti, Cordillera Province, 19°53’S, 63°30’W (1,050–1,140 m)

11. Camiri vicinity (83 km north), road to Itaí, Cordillera Province, 19°21’S, 63°26’W (885 m; Figure 3d)

FIGURE 2. Collecting localities in Santa Cruz Department, Bolivia: (a) road to Bella Vista near Cuevas; (b) Refugio Los Volcanes; (c) Potrerillo del Guenda Reserve; and (d) Flora and Fauna Hotel near Buena Vista.

FIGURE 3. Collecting localities in Santa Cruz Department, Bolivia: (a) Pampagrande; (b) Samaipata; (c) above Achira (Vicoquin Region); and (d) north of Camiri.

Additional localities have been sampled in other departments including Tarija, Beni, Pando, Cochabamba, and La Paz, the most productive of which are listed here and depicted on Figure 1. These localities have shown the greatest percentage of new country records for Bolivia of species previously known from countries adjacent to Bolivia (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Peru):

12a. Riberalta vicinity, Beni Department, Vaca Díez Province, 11°00’S, 66°04’W (130 m)

12b. Las Piedras and Agua Dulce vicinity, Pando Department, 11°03’S, 66°11’W (129 m)

13. Villamontes vicinity, Tarija Department, Gran Chaco Province, 21°19’S, 63°15’W (360 m)

14. Ibibobo, Tarija Department, Gran Chaco Province, 21°32’S, 62°09’W (325 m)

15. Villa Tunari vicinity (Hotel de Selva El Puente), Cochabamba Department, Chaparé Province, 16°59’S, 65°25’W (340 m)

16. El Sacta, Cochabamba Department, Carrasco Province, 17°30’S, 65°00’W (220 m)

17. Rurrenabaque, Beni Department, José Ballivián Province, 14°26’S, 67°32’W (220 m)

Lack of logistics and difficulty of access dictated that most survey work be done at localities below 2,000 m. This combined with the need to work during the rainy season (the most important biological trigger for insect emergence) when primitive roads can become impassable makes it easy to understand the challenge of surveying mountainous terrain. Nevertheless, in the future such areas are likely to receive more emphasis from Bolivian Cerambycidae Project surveyors.

COLLECTING METHODS

Longhorned woodboring beetles have been collected using many different techniques. Species that are large or brightly colored and diurnal are easily seen moving on tree trunks and branches, fallen trees, or leaves and flowers during the day, when they can be hand collected or netted. However, most species are nocturnal and stay hidden during the day. The collecting technique that is most successful for many of these is lighting via mercury vapor and ultraviolet lights suspended over or in front of white sheets (or walls). Once the seasonal rains begin, it is common on warm, humid, dark nights to attract thousands of insects to these lights and not unusual for them to include 50 to 100 species of longhorned woodborers.

In the daytime, beating trail-side or forest-edge tree foliage and branches and other vegetation is one of the best methods of collecting. By beating vegetation over a sheet, the specimens are dislodged and easily seen against the white cloth, where a fast hand or aspirator can collect desired specimens. This is a very productive means to collect many of the cryptic or smaller species, including nocturnal species that are not attracted to lights. Other productive techniques include Malaise, flight-intercept, and fruit traps. A Malaise trap is a strong tent-like apparatus that intercepts flying insects and funnels them into collecting bottles. These traps can be mounted on the ground or hung high from trees. A flight-intercept trap is a fine-mesh fabric stretched taught across a potential “fly zone” through a forest or trail; collecting trays below are filled with some type of preservative. Flying insects, not seeing the obstruction, upon encountering it drop into the collecting trays. Fruit traps filled with ripe bananas are successful for capturing species that are attracted to the smells of fermentation. The traps are constructed to allow attracted insects to enter the trap but not leave. Each of these trapping methods is likely to collect species not normally encountered by other means.

Last, when woody shrubs and some forest trees are in peak bloom they will attract a diverse fauna of insects. Among them are many species of Cerambycidae. As an example of the productivity of blooms, in 2013 we encountered a small tree along a forested road that was in peak bloom. It was buzzing with insects. By bagging the blossoms with a long-handled net we captured some 20 species of cerambycids in a few minutes. An hour later we repeated the process and were almost as successful. Two days later we revisited the tree and found it devoid of insects as the blooms were then wilting. These techniques, and others, are fully described and illustrated in Evans (2014).

SPECIMEN DEPOSITION

All the holotypes and approximately half of all recently collected material from Bolivia are deposited in the Museo de Historia Natural Noel Kempff Mercado in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia. Other specimens, including paratypes, are deposited in various museums in the United States and Brazil, including the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History (Washington, D.C., USA), the American Coleoptera Museum (San Antonio, Texas, USA), the Florida State Collection of Arthropods (Gainesville, Florida, USA), the Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), and the Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo (São Paulo, Brazil), as well as in author Steven W. Lingafelter’s personal collection (Hereford, Arizona, USA).

PREPARATION OF PHOTOGRAPHS AND FIGURES

For imaging, specimens were first cleaned using alcohol and a fine camel-hair brush. Habitus images were obtained using a Visionary Digital imaging system. The system consists of a 64 mm fixed macro lens affixed to a Canon EOS 40D digital SLR camera. A Dynalite M2000ER power pack and Microptics ML1000 light box provide illumination. Image capture software is a proprietary application of Visionary Digital; images were saved as TIF files, and the RAW conversion occurred in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 1.4. Image stacks were montaged with Helicon Focus 4.2.1. Further image processing and enhancement, including all maps, was done in Adobe Photoshop CS4 and CS6.

GUIDE TO SPECIES ACCOUNTS

The 500 species accounts that follow are grouped by subfamily and tribe (each noted in the heading) and are alphabetically arranged within those groups. Authorities are given for all species. Parentheses around the author and year indicate that the genus name is different from the original species description; no parentheses indicate that the species is in the same genus as originally described. Each record includes a photo of a pinned specimen (digitally enhanced and cosmetically improved to remove the pin and foreign objects). This photo is not necessarily to scale for individual specimens or relative to other photos in the book; rather, it is printed at the largest size that will show fine detail and still accommodate the text of the species account.

Each account includes a distribution map for Bolivia that shows each locality from which specimens were collected. The text of the species account includes, in approximate order: the size range; distinctive characteristics such as color, pubescence, and other structural features; comments on known biology, such as hosts, seasonality and behavior; indications of how specimens are collected, such as with lights or by sweeping vegetation; and an overview of the distribution of the species with specific reference to known localities in Bolivia.

Measurements (in mm) in the species accounts represent the length of the insect from the front of the head (or mandibles if they extend past the head) to the end of the elytra (or any protruding structures if they have them) but exclude the antennae. The diagram in Figure 4 and the glossary that follows label and define parts of the cerambycid anatomy that appear in the species accounts.

FIGURE 4. Anatomy of a typical longhorned beetle. Stizocera delicata Lingafelter, from Flora and Fauna Hotel, Santa Cruz, Bolivia.