In the early days of the Behavioural Insights Team, Rory was finding that his commute from the London suburbs combined with long hours at the office and the occasional post-work drink meant that he wasn’t getting as much exercise as he was used to. The regular football and rugby training sessions that Rory always had at school and university were on the wane and he started to notice that he was developing a serious beer belly. So Rory did something that a lot of us do at some point in our lives: he joined a gym. This gym had pretty high monthly membership fees, but Rory actually viewed this as a plus point. Just knowing that this monthly expense was burning a hole into his pocket would be enough to keep him using the treadmills and pumping iron. He would always feel the need to get his money’s worth. Or at least, that’s what he thought.

Several months and hundreds of pounds later, Rory decided to end his subscription. He was barely ever going. And in any case, he felt that he’d worked out what the problem was and how to fix it. Rory reasoned that the issue wasn’t his lack of motivation or the gym per se, it was its inconvenient location. So when he discovered that there was in fact a gym in the basement of the Treasury building in which the Behavioural Insights Team was then based, he decided to join up there instead. It wasn’t as snazzy as the first gym, but it being so close to his desk would mean that he could arrive early for work, do a quick workout and then head up to the office feeling bright and fresh. He could even pop downstairs during his lunch hour to help work up an appetite and burn a few calories. It seemed like a brilliant, flawless plan. And it was, for at least the first week, when he managed a couple of workouts before work and squeezed in a lunchtime run. But by the second week, he was already finding his attendance waning and thereafter he started to find that he was going even less regularly than he was going to his old gym.

Ironically, the fact that the gym was so close turned out to be more of a hindrance than a help. Because it was right there, he could always tell himself that he’d go tomorrow. It’s just that tomorrow never came. Something always seemed to come up. He’d need to finish a report or a briefing for a minister. A Behavioural Insights Team colleague might suggest they talk something over at the pub rather than leaving it till the next day. Rory’s wife Elaine might suggest they go for dinner after work. All these things seemed to be either more important or more enjoyable than running on a treadmill surrounded by Lycra-clad Treasury colleagues. Especially when he could always go to the gym tomorrow. Once again, Rory was, in the words of a famous paper on this exact subject, ‘paying not to go to the gym’.1 But thankfully, he happened to know a technique that would help him navigate around them. He was going to commit himself to going to the gym in the future by putting in place a ‘commitment device’.

Rory decided that, to get back to his previous levels of fitness, he would need to go to the gym at least twice a week. Given that he’d failed to go to the gym more than a handful of times for the previous year, this felt stretching but realistic. He then commandeered the Behavioural Insights Team white board, which at the time was located on the wall in the middle of the office, and turned it into our first commitments board. Rory wrote his commitment on the board: ‘I will go to the gym twice a week for three months’ it read. By writing down his commitment and displaying it publicly, Rory was well aware that he was subjecting himself to a classic behavioural technique which would make it more likely that he’d achieve his goal. He knew that, once a commitment has been made, written down and made public, he would feel a strong sense of duty to remain consistent with his pledge.

He then did something else that he knew would make it even harder to back down. He appointed a commitment referee to help police his efforts and judge whether or not he’d been successful, and set a penalty were he to fail. Owain stepped up to the mark to play the role of commitment referee, which meant that he would judge whether or not Rory had indeed fulfilled his initial pledge, and whether he deserved the penalty he had set himself should he fail. We’ll go much deeper into the question of how to penalize or reward yourself in later chapters, but for now it’s enough to know that Rory’s penalty was a severe one: he would have to don the shirt of the football team he loathed (Arsenal – the nice twist being that this is Owain’s team), get it made up with the number and name of their best player (who at the time was Robin van Persie) and wear it to the office for a day. At first, it remained a struggle mustering up the energy to head to the gym twice a week, but the pressure to fulfil his pledge coupled with the potential pain of the Robin van Persie shirt outweighed any of the initial suffering. Then, after a few weeks, Rory found that he had begun slipping into a routine. Suffice to say that Rory achieved his goal and Owain never got to enjoy the moment of seeing Rory in an Arsenal shirt. Perhaps more importantly, since then we have both used commitment devices in our personal and professional lives, from helping us to save money, to setting up overseas Behavioural Insights Team offices, to spending more time with our families.

Making a commitment is relatively simple to do. But it won’t surprise you to learn that there are a number of small things that can help to strengthen your commitment, and make it more likely that you’ll follow through. The three golden rules are:

Make a commitment. The first step is to make your pledge, and to ensure that this is clearly linked to your headline goal and the small steps you have created to help you achieve it.

Make a commitment. The first step is to make your pledge, and to ensure that this is clearly linked to your headline goal and the small steps you have created to help you achieve it.

Write it down and make it public. You’re more likely to stay true to your commitment if you write it down and make it public in some way.

Write it down and make it public. You’re more likely to stay true to your commitment if you write it down and make it public in some way.

Appoint a commitment referee. A referee will help you stay true to your core objective. The ideal person is someone you trust but who will not be afraid to mete out penalties if you fail.

Appoint a commitment referee. A referee will help you stay true to your core objective. The ideal person is someone you trust but who will not be afraid to mete out penalties if you fail.

Rule 1: Make a commitment

Imagine that it’s a Wednesday night. You’ve had a hard day at work, and don’t have much food in the fridge. So you decide that you need to unwind: you’re going to get a takeaway and watch a film. You order a pizza, turn on the television and are confronted with a choice. On one channel is a film that you know will be entertaining, but lowbrow. Let’s imagine it is Pitch Perfect or Batman v Superman – neither of which will leave you analysing the complex plot line once it’s over. On the other channel, however, is an entirely different type of film. Much more highbrow. Let’s say it is 12 Years a Slave or Lincoln. Both these films score lower in terms of sheer entertainment, but you’ve been meaning to watch them for a while, and you think they will be interesting and entertaining in a way that Pitch Perfect is unlikely to be. Faced with this choice, after a hard day at work, which do you go for? Highbrow or lowbrow?

If you’re anything like behavioural science professors Daniel Read and George Loewenstein and their collaborator Shobana Kalyanaraman, you will have experienced always intending to watch a more highbrow film, but then, when push came to shove, typically winding up watching the lowbrow alternative. Highbrow movies, people reason, are those that they have always intended to watch or would have liked to have seen in the past (and probably wouldn’t regret having seen, once the film was over), while lowbrow movies are likely to be more immediately ‘fun but forgettable’. The researchers explain that, when they first started discussing the highbrow film phenomenon, they observed that many of their friends intended to see Schindler’s List, but many took weeks before they finally did see it, and many often never got around to it at all.2

Like all good behavioural scientists, Read, Loewenstein and Kalyanaraman did not stop at making an insightful observation and then moving on with their lives. They decided to devise an experiment to see how the phenomenon might pan out when people were confronted with different kinds of decisions. So they gathered a group of students, randomly divided them into two different groups and got all of them to choose three different movies to watch on three different nights. But there was an important twist in the two groups. The first group would choose each of the films on the day that it was to be watched. These students would be the equivalent of the person coming home from work, deciding there and then which film to watch. But the second group chose all three movies on the first day. So while the first day was effectively the same for both groups (choosing the movie on the same day that you watch it), days two and three were different – the second group were making choices about what to watch in the future, whereas the first were always grounded in the present. The question was whether, by encouraging the students to commit to future choices, the decisions that they took would better reflect what they intended to do (Schindler’s List) rather than what they chose to do on the spur of the moment (Batman v Superman). And that is exactly what happened. In the first group, the one that got to choose a film every day, most of the students chose a lowbrow film each time. But in the second group, a lowbrow film was only chosen most frequently on the first day. For subsequent days, when the students were thinking more about what they intended to do, they were more likely to choose a highbrow film.3

This simple experiment might seem like a frivolous foray into the world of cinematography. But it also teaches us something profound concerning how we think about the future. We tend to prefer immediate ‘vices’ (lowbrow films, burger and chips, surfing the internet at work) to immediate ‘virtues’ (highbrow films, grilled chicken and salad, getting that final report written), ‘since the vice offers a larger reward in the present’.4 Behavioural scientists call it ‘present bias’ – we prefer rewards today over bigger gains tomorrow, and delay effortful decisions and actions, even when we know we probably shouldn’t. We prefer cake and relaxation today, and brown rice and exercise tomorrow. We spend money in our pocket today over saving for retirement. We fail to tackle global problems like climate change because the costs are borne upfront but the benefits of acting are felt long into the future. It’s almost as if we have a present self, who tends to like ice cream and beer, and a future self who has a different, more virtuous set of preferences, such as abstaining from dessert and drinking sparkling water. The problem, of course, is that at some point our future selves will in fact be our present selves. And this is the clever part of Read, Loewenstein and Kalyanaraman’s study. They were able to show that by getting our present selves to think about our future self, and bind them into a decision in advance, it is possible to overcome this temporal hurdle. That, in essence, is what a commitment device is. It’s a pledge made by your present self that binds your future self to a more virtuous path, in the knowledge that in the future it will be your present self taking the decisions.5

So if you know that you are going to find it hard, like Rory, to get to the gym regularly, or if you know that it’s going to be tough to keep up the language lessons because your future self might prefer going to the pub instead of conjugating verbs, you should think about setting yourself a commitment. In the next sections, we’ll learn about how to strengthen these commitments. But for now it’s enough to know that making a commitment – to go the gym, to attend your language lessons – is the important, first step. When you do this, you can either commit to your ultimate objective (running a marathon in under four hours), or you can link it with the most troublesome steps that you have identified to achieving that objective (going for a run three times per week). And you should link this commitment to the rewards or penalties you set yourself (how to set these incentives is the subject of the ‘Reward’ chapter). That is the best way of making your commitment binding, with definite consequences if you fail to follow through. If you do all of these things, you will likely find that you have a strong desire to remain consistent with the promises that you have made, and you will feel uncomfortable about breaking the commitment you make. This anticipated discomfort will help you stay on course.6

One of our favourite examples of a commitment device being used to help people achieve a stretching goal relates to savings and employs all of these mechanisms. Some 700 individuals were given the option of opening either a straight savings account or a commitment savings account, which required clients to pledge not to withdraw funds until they reached a specific goal they had set themselves. The savers could either decide to set a goal linked to when large sums of money were needed (such as Christmas or for school), or they could set one linked to a set amount of money. They had complete flexibility over what that goal might be, but once the goal was set, it was explained that the commitment would be binding. In other words, they would only receive the money if they met their target or once they reached their target date.7 After twelve months, the researchers measured the average bank account savings of those who had been offered the commitment accounts relative to a control group of people who had not, and they found that average savings balances increased by 81 per cent for those who’d been offered the accounts.

One of the reasons that we like this study is that no one was forced to take up the accounts. In fact, there were good grounds for thinking that no one would: they offered no financial incentives and prevented people from accessing money at short notice. And yet between a quarter and a third of everyone given the opportunity to open a commitment savings account decided to take up the offer. That so many people were prepared to take up the accounts was an important finding in its own right, demonstrating that a decent proportion of savers were sufficiently aware of their cognitive frailties to bind their future choices.8 And in fact when we stop to think about it, we routinely use commitment devices all the time. Disgruntled parents ask their children not just to tidy their rooms, but to promise to do so. We schedule workouts with a partner in part because we know that failing to follow through will disappoint the other person, or we enter half-marathons six months in the future as we know that this will force us to train. Similarly, we ask our colleagues what they will do before the next meeting, to increase the likelihood they will follow through. There is even evidence showing that people are starting to buy their food online in part because it helps them to commit to purchases that are in line with their future self’s preferences, and thus to avoid making the impulse buys that their present self craves.9

So it appears that, in all kinds of fields, we seem to understand intuitively that we will face temptations in the future that our current selves would rather our future selves avoided. We also seem to understand that a good way of avoiding these paths is to commit to future action. So, once you have set your goal and worked out the steps you need to achieve it, you should commit to achieving that goal and/or the separate steps to get there.

Rule 2: Make your commitment public and write it down

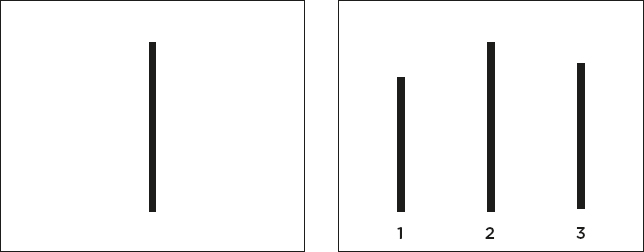

One of the most famous experiments in social psychology was a test of ‘conformity’ – in other words, of how susceptible we are to social pressure from a group. In the classic experiment, conducted by Solomon Asch in the 1950s, participants were shown two cards. One had a line on it, the other three lines. The challenge was to say which of the three lines matched the single line on the other card. It was a deceptively simple task, such that in normal circumstances, individuals matching the lines would make a mistake less than 1 per cent of the time (and to be honest, you have to question what the 1 per cent were doing when asked the question). You can try it for yourself below – which of the lines in the row of three matches the line by itself?

But this being a psychology experiment, the real test was not whether it was possible to match the lines. It was what happened if you got someone to contradict your judgement about which lines matched. In Asch’s experiments, an individual is put in a room with a group of actors who are instructed to get the answers deliberately and consistently wrong. The test is whether the individual participant is willing to give a clearly erroneous answer as a result of the social pressure exerted by the group. If this is the first time you have come across such experiments, you may be surprised by the core finding – which is that the individual accepted the misleading majority’s wrong judgements 37 per cent of the time. In the 1950s, in the aftermath of the Holocaust and the beginning of the Cold War, this was a worrying finding: it seemed we were much more likely to succumb to group pressure than we might like to think. ‘That we have found the tendency to conformity in our society so strong that reasonably intelligent and well-meaning young people are willing to call white black is a matter of concern’, wrote Solomon Asch.10 But while these headline findings were indeed surprising and potentially worrying for social psychologists at the time, it was also recognized that small changes in the way that an individual’s view was put forward would have a considerable effect on their willingness to stick to their guns.

Following in the lead of Solomon Asch, Morton Deutsch and Harold Gerard ran the experiments again, but with a series of subtle variations that were designed to examine whether different kinds of commitments might strengthen the resolve of the participants.11 Some people participated in the same way that individuals had done in the original experiments. They saw the lines, made a judgement in their heads and were then subjected to the views of others. But others had a slightly different set-up. Rather than just keeping it in their heads, they were told to write down their judgements before telling others what it was. The question was whether writing it down might strengthen the individual’s commitment to the answer they had arrived at and would prevent them being so easily swayed by group pressure.12 The experiment results, when no one wrote down their answers, were very similar to the original Asch experiments. Individuals felt the same pressure to conform and continued to make a series of erroneous judgements about the lengths of the lines they’d seen. But when the judgements were written down in advance on a piece of paper, the errors were hugely reduced – by more than three-quarters.13

This niche set of experiments, conducted sixty years ago, might feel a world away from the goals you set yourself. But they reveal a set of common truths about human behaviour that we can use to strengthen the commitments we make. The first, simple step, is to do exactly what the individuals in the re-running of the experiment did: write your commitment down. You can write it on a board in a public space, as Rory did with his gym commitment. Or you can write it on a piece of paper in front of your commitment referee (we’ll meet these characters in the next section). Writing down a commitment, and even going as far as signing your name against the pledges you make, is a surprisingly effective way of encouraging consistency in behaviour – one of the reasons that the technique is employed so frequently in modern life. We sign contracts committing us to employment, getting married and buying houses. These are only considered to be binding – to commit us to future action – once we’ve written, dated and signed our name. Organizations around the world ask their employees to set themselves objectives for what they will achieve through the year, which are written down and agreed with their managers. Even shopping lists seem to be effective ways of changing the way we shop. It’s not just that they help us to remember what to buy, they also help us to avoid impulse buys in a similar way that online shopping does: by pre-committing us to future action.14 So once you have made a commitment, write it down.

If writing the commitment down helps to raise the stakes of a commitment, then making it public can turbocharge it. In other words, you shouldn’t keep your written commitment to yourself. Indeed, one of the things that made the written commitments powerful in the Deutsch and Gerard studies was the very real possibility that these prior commitments would be revealed publicly. To understand the mechanisms at play in a public commitment, we like to go back to a fun study using a scenario that will be familiar to us all, conducted by the psychology professor Thomas Moriarty.15 It was first brought to our attention by Robert Cialdini, whose classic book Influence has informed the work of the Behavioural Insights Team over the years.16

The scene is a summer day at Jones Beach in New York. Imagine that you’re there now and think about how you might respond to the following scenario. Out of the corner of your eye, someone comes and places a blanket on the beach within five feet of you and turns on a portable radio to a local radio station at a fairly high volume. After a couple of minutes, the person asks if you have a light for the cigarette they are about to smoke and then walks away, out of sight. A few minutes later, a shady-looking man appears. The man walks up to the blanket, picks up the radio (still playing loudly) and quickly walks away with it. What do you do? If you’re anything like most people in the study, you do nothing. You allow the thief to take the radio and do not intervene. Why would you, you might ask yourself – you could be risking personal harm, and you’re not sure who the radio owner is anyway. But now imagine exactly the same scenario, but with one subtle twist. Rather than asking you for a light, the antisocial radio enthusiast approaches you before they head up the beach and says, ‘Excuse me, I’m going up to the boardwalk for a few minutes…would you watch my things?’ In other words, they elicit from you a direct, public commitment. What do you do in this scenario when the thief appears to take the radio? If you’re like the beachgoers of New York, after publicly committing to watching the things of a total stranger you will become a completely different person. When the experiment was run, 95 per cent of people intervened – only one in twenty failed to challenge the thief.

Much like writing down a commitment in advance, making it public creates a stronger incentive to be consistent than if we had simply made the pledge in our heads. Whereas the process of writing down a commitment internalizes the social pressure in which we hold expectations about own behaviour, making it public exposes this internal pressure to others. It’s the consistency of our behaviour in the eyes of others that is important.17 You’ve said that you will look after someone’s things; now how will you feel when asked what you did by the person who you made the commitment to? The need to maintain public consistency is one of the reasons why hung juries are more likely to occur when jurors are made to express their initial opinions through a visible show of hands rather than by secret ballot. Once jurors state their initial views publicly, they become reluctant to change these views publicly.18 If we stop to think about it, we will realize that we already make use of public commitments – often for those things that are considered to be the most important of all the decisions we’re likely to make. There’s a reason, for example, why we invite people to our weddings to hear us say our vows, rather than just agreeing to be married to our spouse. There is even some evidence that shows an inverse relationship between the number of people you have at your wedding and your subsequent chances of getting divorced. Couples who elope are more than twelve times more likely to end up divorced than couples who get married at a wedding ceremony with more than 200 people.19 There are, of course, many confounding factors at play here – it may well be that couples who get married on their own are more likely to be doing so impulsively. Nevertheless, this is strongly consistent with other work suggesting that making your commitment public in front of a group of family and friends may provide you with the motivation and networks needed to make you more likely to stick together ‘for better or worse’.20 So think about ways you can make your commitments public – for example, you may commit to your team to send weekly updates on key decisions, or commit publicly on your organization’s website to publish annual reports.

As with many other aspects of a think small approach, however, the way you make your commitment public is important. Think back to how Rory made his commitment to get fit. He didn’t just announce his goal to his colleagues and be done with it. There is some evidence that just announcing your intentions to reach a goal in this way can backfire, and doesn’t create the requisite bind of consistency. It seems that we get a small buzz from telling people about our goals, regardless of whether we actually then follow through on our intentions – especially where these are likely to carry some social kudos (such as writing a novel or recycling more).21 But something different happens when we go a step further. So that’s why Rory didn’t just announce his good intentions. He set out publicly the steps that he was going to take to achieve his goal, by writing the latter down on the office whiteboard. This is the hallmark of a good commitment device. It’s also why it’s important, in applying a think small approach, to link your commitment to the plan-making and goal-setting activities that were the focus of the previous chapters. It makes a big difference to commit to undertaking the specific steps you need to make to achieve your goal, rather than simply declaring your intention to achieve something. As ever, the small details matter.

Rule 3: Appoint a commitment referee

There is a great scene in the American comedy series Curb Your Enthusiasm in which Larry David is asked by a friend to help her to avoid eating dessert by playing the role of her ‘dessert referee’.22 He is asked not to let her eat any of the fabulous desserts that she has prepared ‘no matter what’. However, later that evening, she heads to the dessert table and picks up a large piece of cake, which Larry spots and prevents her from eating, taking the cake out of her hands.

Friend: ‘I’m just going to have a bite.’

Larry: ‘No, no, no. You told me specifically not to let you have any dessert.’

Friend: ‘I appreciate it Larry, but I changed my mind.’

Larry: ‘Yes, but you said “no matter what”.’

Friend: ‘But you know what, now I’m changing it. And I’m saying thank you for helping me but I’m going to have some cake.’

Larry: ‘But you can’t change it, that’s why you say “no matter what”. This is the “what”. That’s why you asked me and not those other people, because you knew I wouldn’t let you.’

Group: ‘Come on, Larry, let her have it.’

Larry: ‘But she said no matter what.’

Anyone who’s ever watched Curb Your Enthusiasm will not be too surprised to learn that, following Larry David’s intervention, the scene descends into chaos. But though his execution may have left a lot to be desired, he had stumbled across a number of principles that the latest behavioural science research is showing can be of great importance in helping you stick to your goals. The first was Larry’s friend’s recognition, at the heart of all good commitment devices, that her future self would face temptations that would be challenging to resist. The second was the understanding that you are more likely to be able to follow through on your commitment if you appoint someone to act as your commitment referee: someone who will monitor your compliance and determine whether you have succeeded in meeting your goal.

Two of the behavioural scientists who’ve thought most about the importance of commitment referees are Dean Karlan and Ian Ayres. They also helped to set up the website stickK.com, specifically to help people make and follow through on their commitments. StickK.com encourages people to create a commitment contract – a binding contract you sign to help you follow through on your intentions. This is very much in line with the principles we have already seen – writing it down and making it public. Over the years Karlan and Ayres have gathered lots of data on which commitment contracts are most likely to be met and have found that one of the most effective ways of achieving your goal is to appoint a commitment referee. People who have a referee are about 70 per cent more likely to report success in achieving their goals than those who do not.23 But as Karlan and Ayres have realized, and Larry discovered to his peril, the appointment of a referee can be fraught with complications. When Ayres came to present some of his latest findings to the Behavioural Insights Team, he gave two important pieces of advice. The first is that you have to trust that your referee will be fair. It’s no good appointing someone who will revel in your ill fortune, or conspire against you. A poor choice of dessert referee, for example, would be someone who enjoys waving tiramisu in your face in order to see you fail. The second, even more important consideration is that you have to believe that your referee will be prepared to enforce the commitment by following through on any penalties (or rewards) that you have set (the subject of the next chapter).

Many people might think that someone very close to them (such as a romantic partner) might be best placed to be their commitment referee. But while the evidence suggests that it is effective to make your pledge in front of a romantic partner (i.e. the make-it-public part),24 these same people can often make poor referees precisely because they are more understanding of any noncompliant behaviour (‘You’ve had a hard day!’). In other words, they may be more likely to conspire with you in unhelpful ways (‘Why do you have to go to the gym tonight when we could be going out?’) and are therefore more likely to be unwilling to enforce the terms of your commitment contract. So Ayres’ advice is not to designate ‘either an enemy or a soft-hearted friend to be your referee’. For this purpose, a trusted colleague might be less likely to conspire with you than your boyfriend or girlfriend. When Rory set about committing to his new exercise regime, for example, he knew that Owain was much more likely to enforce his penalty than his wife, who might be more understanding if he failed to visit the gym often enough – particularly if it was because, for example, they both had plans to visit the cinema or go for dinner that evening. In hindsight, the only mistake that Rory and Owain made in setting the terms of the commitment was that the punishment represented a conflict of interest for Owain: it would have given him a significant amount of joy to see Rory having to wear an Arsenal shirt. Thankfully for Rory, this never came to be.

The use of commitment referees has huge potential in all kinds of areas. We saw in the example that opened this book how commitment devices don’t just help you to meet your personal goals, but can also be useful for helping you to encourage others to achieve theirs at work too. The programme we put in place in job centres helped to get people back to work faster. At the heart of that new programme was a focus on setting stretching goals, breaking them down and then committing to each of the separate activities. Paul committed to working on his CV, making applications for jobs and buying new tools to help prepare him for the jobs he was applying for. He specified when he was going to do these things (part of his plan-making activities). And he did all of this in the presence of Melissa, his job advisor, who acted as Paul’s commitment referee. There is a world of difference between Melissa asking Paul whether he has undertaken a set of administrative tasks that are requirements for approving his benefit claims and acting as someone’s referee in relation to the goals that they themselves have committed to. When Paul signed his commitment contract with a pledge to ‘sign up to five job sites’ that week and to bring an updated CV and cover letter in for his next meeting with Melissa, it was him who was making the commitments. He’d be letting himself down if he failed to follow through, but equally Melissa would have a concrete pledge of Paul’s with which to hold him to account. Notice, however, that Melissa’s role was not to find out where Paul had gone wrong. She was not doing the equivalent of waving tiramisu in the face of someone who was trying to avoid eating cake. Rather, she was there to help and support Paul, but she was also able to step back and judge whether or not Paul had achieved his goals.

Up to now, we’ve assumed that your commitment referee will help you to monitor your progress and be present when you’re setting your goal in the first place. But we think that over the coming years, a range of new technologies may well start providing us with this service in ways that cut down on any of the administrative effort required. The rise of smart phones, wearable devices and apps enable us to track physical activity, spending, sleep and our weight. It might be that, over time, these new devices can be combined with the insights that show the benefit of having a trusted, nominated individual to help you follow through. There are already some emerging examples of this kind of interaction in practice – examples that combine smart technology with a nominated commitment referee. One such example is GlowCaps,25 which are designed to help people adhere to their medication. GlowCaps are wireless-enabled caps for standard prescription bottles that light up and play a ring tone to remind you to take your medication. The device records information concerning each time the medicine bottle is opened, and reminder calls are sent to the patient if the bottle isn’t opened within one to two hours of the designated time. In addition, patients are encouraged to nominate a commitment referee (for example a family member, friend, caregiver or doctor) who will also receive an emailed medication adherence summary each week. The hope is that the nominated referee will act as a form of external support to help boost medical adherence.

Commitment referees, then, can come in a number of different forms, but several principles seem to be important in ensuring that your referee will help you achieve your goals. In particular, we’ve seen how important it is to get the right kind of referee – someone who is fair but also willing to administer the penalties or rewards you set yourself. We’ve also seen how the previous steps, in particular writing down your commitment, help to ensure that everyone is clear about what the goal is, so that it can more easily be enforced. All of these small steps, we hope, should make it easier for you to stay motivated, and easier for your commitment referee to keep you on the straight and narrow.

Commitment devices are useful because our present selves seem to have different preferences from our future selves. If we weren’t aware of this conflict, it would be hard to commit to anything. But thankfully, it seems that human beings know full well their own frailties, which is why many of us seem prepared to lock ourselves into choices that bind future action, like opening savings accounts that keep our money locked up until we reach our savings goals. So commitment devices work, first and foremost, because we are prepared to enter into them due to an existing awareness of our self-control issues. But once we have made them, they work for a different reason; when we have made a commitment, we encounter pressures to behave consistently with the pledge that we have made and knowing this enables us to strengthen the commitments we make. By writing down our commitments and making them public, we not only increase the internal pressure upon ourselves to behave consistently with our commitment, but also feel interpersonal pressure to do the same. And this can be further enhanced by appointing yourself a commitment referee. Not someone who is there to trip you up or help find excuses, but someone who can provide the support you need to keep you on track. That commitment referee will also be the person who is best placed to decide whether or not you are deserving of the reward you set yourself. How you do this is the subject of the next chapter.

Make a commitment. The first step is to make your pledge, and to ensure that this is clearly linked to your headline goal and the small steps you have created to help you achieve it.

Make a commitment. The first step is to make your pledge, and to ensure that this is clearly linked to your headline goal and the small steps you have created to help you achieve it. Write it down and make it public. You’re more likely to stay true to your commitment if you write it down and make it public in some way.

Write it down and make it public. You’re more likely to stay true to your commitment if you write it down and make it public in some way. Appoint a commitment referee. A referee will help you stay true to your core objective. The ideal person is someone you trust but who will not be afraid to mete out penalties if you fail.

Appoint a commitment referee. A referee will help you stay true to your core objective. The ideal person is someone you trust but who will not be afraid to mete out penalties if you fail.