WE’RE ON THE road, babe! It’s heady stuff. New blood, new places, new faces. Direct from San Francisco, ladies and gentlemen, the one and only Grateful Dead! Our audience is growing daily. After the Monterey Pop Festival and the Summer of Love, the word goes out and all of a sudden the Grateful Dead are — rock stars! Sort of.

We’re getting our first taste of what the future holds in store: a steady diet of greasy burgers and cardboard in-flight dinners, burrowing from one backstage cinderblock bunker to another through interchangeable airport lounges and indistinguishable hotel rooms — that terrifying painting of windmills that follows us from town to town! And just think, if we’re lucky we may be doing this shit for a very long time to come.

Bill Graham indulges us by setting up our first international tour. Okay, Canada isn’t exactly an exotic foreign land (and we’ve been there once before, for a phony Trips Festival in Vancouver). Still, it’s our first big, official (as we can get) road trip.

July 31 to August 5,1967. A week in Toronto’s O’Keefe Center with the Jefferson Airplane as headliners. It’s Graham’s first out-of-town promotion, the beginning of his true world-class megalomania.

The O’Keefe Center is a newly constructed concert hall, plush and huge,just like Radio City Music Hall. We aren’t all that well attended in Toronto. The first couple of nights are sold out, but after that the hall is barely half full. Bdl Graham has been perhaps a wee bit optimistic.

There is a hippie area in Toronto called Old Town that’s similar to the Haight-Ashbury, filled with American kids escaping the draft. They tell us the real action is in Montreal and we all want to go so Graham reluctantly books us for an afternoon gig at the Youth Pavilion at the Montreal Expo. We’ve already got a head of steam going about doing a free concert. Word has spread, and we are constantly asked about it, especially by the underground press.

“We hear you play for free in the park in San Francisco — are you planning on doing anything like that in Canada?”

And Lesh goes, “Hell, yeah, we’ll play some free concerts.You guys get it together and we’ll do it.” Thanks, Phil!

On Sunday, the morning after the last gig at the O’Keefe, both bands pile on a bus and head for Montreal. We get off at the Place Ste. Marie, a square downtown between two featureless skyscrapers. There is a fountain and iron railings and brickwork everywhere. It’s clearly going to sound horrible. In the middle of the square is a tiny stage about the size of a Frisbee with thirty or forty thousand kids milling around it. I guess word got out!

It’s so crowded it’s scary. We have to carry in the gear by passing it over the heads of the crowd. There is no place to get on and off the stage. Each band manages to play for about an hour and then we pack the equipment up and wrestle it all the way out again, and put it on the bus to the Expo.

After the Expo Show (on a rotating stage!) the Airplane, stars that they are, head down to do a Canadian Broadcasting System show. We are cordially not invited along, and they unceremoniously dump us on a sidewalk.

“Fuck it,” says Jerry, “this calls for Millbrook.”

Millbrook is LSD East,an estate in upstate New York where Timothy Leary is living. We’ve been talking about going to see the Reverend Tim, on our way down to New York. Ron Rakow, our confidant, and his girlfriend, Peggy Hitchcock, are on tour with us, and it’s at the Hitchcock family estate that Leary is holding court. Peggy comes from one of the richest families in America and Ron is a banker who’s taken acid and dropped out.

Our next date is in Detroit, Michigan, several days off. We have some free time and it is still easy to talk ourselves into doing some really off-the-wall thing. It’s an amazing lark and I don’t think we’re ever quite like that again. Everything from here on in will be a little more plotted, and as a group only once will we ever put ourselves in such jeopardy again.

Peggy Hitchcock knows some people in downtown Montreal, so we schlep all the gear over there in taxis and pile up our suitcases and equipment in front of their house. Fortunately Peggy has credit cards, and she and Ron run around town picking up enough rent-a-cars so that we can load all this stuff up and get out of town. In the meantime we are basically camping out on the sidewalk in front of a fancy town house.

I take the last car to drive down with Peggy, Ron Rakow, Garcia, and Bobby Weir. We’re getting ready to go and suddenly discover Weir is not on the bus. He’s wandered off somewhere in the jungle of downtown Montreal. It is his nature to get lost. We find him sitting cross-legged in a comic book store.

“Hey, man, dig this, the Incredible Hulk, ish number three!”

We don’t get out of Montreal until nightfall, and then drive all night in a convoy of rented cars down the New York Thruway. With me in front are Pig, driving, and Veronica riding shotgun. In the back are Peggy, Jerry, Mountain Girl and Sunshine, and the other car has everyone else. We all go in tandem down to the fabled acid palace of Millbrook.

We call Billy Hitchcock on the way to ask if we can stay in the bungalow and he says no. So we go there anyway! It’s a five-hour drive to Millbrook, and we arrive around six in the morning, seriously frazzled and dingy from smoking STP. STP is the new drug this summer and it’s what keeps us rolling. Like DMT, it’s an instant trip. It has about a two-hour life, but it doesn’t reek like DMT. DMT has this terrible smell when it burns. The band forbids its use onstage because if you smell it you can have a flashback right on the spot. STP comes like a big stick of chalk from which you whittle powder and roll it in a joint and smoke it. We are doing it on airplanes because it doesn’t have a telltale smell. You can roll it with tobacco. And it keeps you up, which we definitely need.

Our initial reception is very cool indeed. Egad! the Hirsute Simian Horrors have descended on us! Peggy takes us to her brother’s big old stone mansion on the grounds, which are huge. The back of the house looks on to rolling hills, with patios and decks and stone terraces cascading down to the swimming pool. Beyond that there are lawns stretching out for miles. Those of us who want to sleep stumble into bedrooms and pass out. Garcia crashes as soon as we get in.

Out of karma or whatever reason, Jerry and Mountain Girl happen to get Billy Hitchcock’s room, the big bedroom in the bungalow. The next day Jerry goes poking around in Billy’s closet, and what does he find but a big fat bag of Acapulco Gold from which Mountain Girl rolls us a couple of bombers and we get really fucking loose and spend a very nice day in the country!

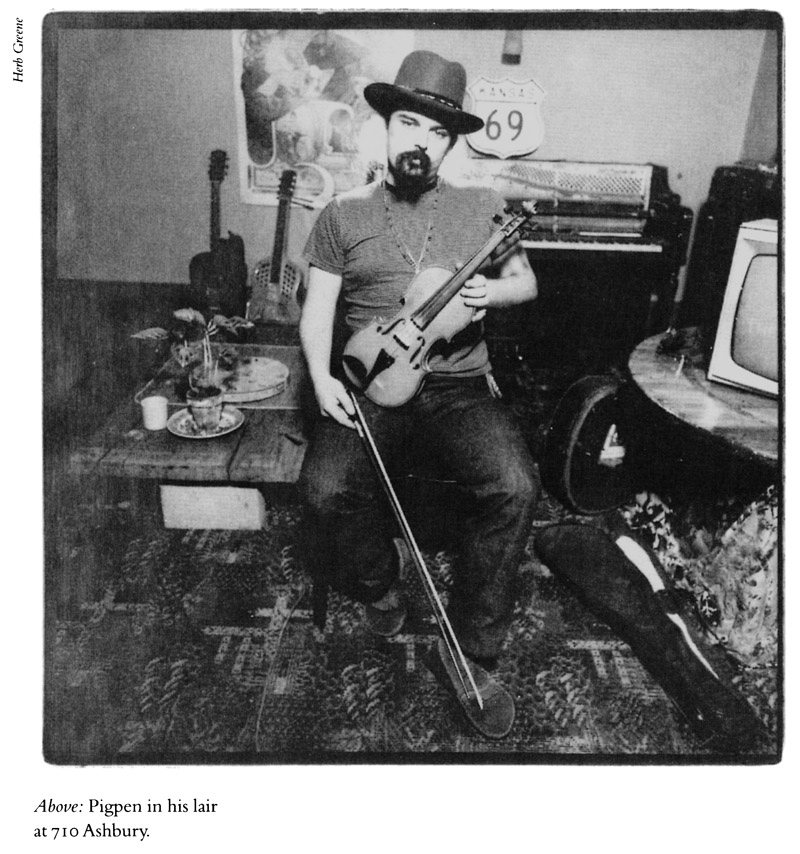

Pigpen is asleep within minutes of arrival. He always looks after himself that way, has to have his critter comforts as he calls them. Raids the liquor closet to get whatever he can find and then repairs to his own bedroom with lots of pillows. Only after he has his crib totally together will he scope out the wenches, see if maybe the maid is amorously inclined.

The rest of us stay up. Lesh and I walk all over the grounds, which are so huge you drive between one residence and the next. We go over to see Tim Leary, who’s ensconced in the main house. It’s a giant wooden structure, three or four stories high, with a huge painting of the Buddha stretching the entire height of one wall. Inside it’s a huge rambling sixty-eight-room mansion where Leary and his flock hang out. He’s all dressed in white and bare feet. Delighted to see us and wants us to set up and play, but we’re all sooo ragged. Nobody wants to haul all the gear out of the cars and put it all back again. Especially me.

On the walls of the Learyites’ abode are little life-affirming aphorisms: a copy of the Desiderata, the latest bulletin from the League of Spiritual Discovery (“You have to be out of your mind to pray”), posters of hairy swamis. There are Hindu ragas playing on the turn-table, and Buddhas and Shivas all over the damn place. And then — what’s this? — there’s a large candlelit room off the kitchen with mattresses on the floor.

“Jesus,” Lesh says, “take a look in here. They’ve got a fucking orgy room, man.”

One of Leary’s acolytes corrects us: “That’s the Psychodrama Room, actually.”

“Yeah, well like I said . . .”

Did we see Tim’s poem, “Homage to the Awe-full See-er” in The Psychedelic Review? Why, no, we must have missed that one.

“How does it go, man?” Like I really gotta know.

Tim sits cross-legged on a beanbag while somewhere in the back ground a sitar drones. Dear God, he’s actually going to recite the damn thing!

At each beat

in the earth’s rotating dance

there is born. . . .

“. . .”

Here he pauses for the entity, the thing in the space between the quotation marks, to enter the room. A heady moment! With breathy articulation, he continues:

. . . a momentary cluster of molecules

possessing the transient ability to know-see-experience

its own place in the evolutionary spiral.

Such an organism, such an event,

senses exactly where he is

in the billion-year-old ballet. . . .

Just as it’s getting truly insufferable, in walks Pigpen. “Hey, where are all the chicks, man?”

Millbrook has become more a small village than an estate. Not only is Leary incapable of turning anybody away, he is by now more famous than the pope. He’s the pope of dope, actually, and we have revised his catchphrase “tune in, turn on, drop out” to read: “plug in, freak out, and fall down.”

Millbrook is just jammed with people and it’s not exactly a fastidious crowd. I’m amazed the place hasn’t burnt to the ground. There are candles and joss sticks burning all over the house not to mention sloppily rolled joints spilling out of ashtrays and balanced on window ledges.

The weather is warm and a lot of Leary’s tribe have lit out for the woods. A mile hike through the forest and we’re in a small Indian village. Hippie Indians. Eight or nine tepees, plus makeshift tents and ramshackle lean-tos. Everybody is into living the tribal life. Babies, dudes, chicks, and dogs. Sitting around smoking pipes and beating on tom-toms. Everybody getting high on Cannabis americanus. Hippies from New York and San Francisco and Mount Shasta and Sweden, all living stark naked in the woods. Loincloths, buckskins, and moccasins are the only acceptable outfits. Here authenticity is everything, but not every aspect of Indian life is faithfully duplicated. These are supermarket hunter-gatherers.

Despite the fact that he hadn’t wanted us here in the first place, the following evening Billy Hitchcock calls everyone he knows in New York and tells them “The Grateful Dead’s at my house in Millbrook and they’re gonna play for us!” provoking a great exodus of affluent acid-eaters and the curious rich from New York City.

The band sets up in a corner of the living room of the bungalow. “Living room” being another colossal understatement. It’s actually a great hall large enough for Beowulf and his soldiers to carouse in. All Billy Hitchcock’s rich friends and all the Learyites file in to see us play. There must have been seventy-five people, plus the seventy-five that were already living on the property. So, that night we sing for our supper. It’s that or wash dishes. I am standing on the terrace smoking a joint when weir straggles in: “Shit,” he says, “this is like a fucking gig!”

The next day we head on down to New York City, to the Chelsea Hotel. Everybody stays at the Chelsea, everyone who has been touched by wings of madness. Painters, perverts, dopers, dealers, poets, poseurs and transvestites (and the odd Belgian traveling salesman who’s misread his guidebook).

On the Chelsea roof there is a penthouse with awnings and a view of the Hudson River. We’re going to play, heaven help us, a free concert on the roof. It is our intention to hit up the hipoisie for contributions to the Diggers’travel fund (Trip Without a Ticket). The invitees have all been instructed to bring their checkbooks.

It’s amazing out there on the roof. A tent has been set up and champagne is flowing. The crowd is principally stockbrokers and bankers and wealthy heads come to see and hear the Dead. All these dressed-up society folks, and here we are literally at the end of our rope, having come from the wilds of Millbrook half drunk and totally stoned on the STP. And we’re trying to make small talk with these people.

“Is it true, Mr. Garcia, that people stoned on acid are immune to radiation?”

“Oh, definitely. Want some?”

“Is it true, Mr. Garcia, that Grace Slick put LSD in the punchbowl at Tricia Nixon’s wedding?”

“That’s a damn lie! I put it in. . . .”

These guys have seats on the Stock Exchange, their great-great-grandparents’ great-great grandparents came over on the Mayflower, they own pet-shop chains, or even whole cities out on Long Island. But we seem to have a wicked effect on these people; they never should have come.

“Jerry, I’d like you to meet Roger Lewis. . . .” The aforesaid Roger subsequently sells his seat on the Stock Exchange and gives away all of his money (well, almost all of it). Later he gets busted in England for selling LSD and moves to Nevada.

“Phil, this is Huntington Hartford’s daughter. You know, the A&P heir? She’s a big fan of yours. . . .”

“Rock, do you know Thayer Craw? You two should really hit it off. . . .”And that, my friends, is the end of that famous old name. She ends up marrying one of the Pranksters.

MEMO TO JOE SMITH, WARNER BROS. RECORDS

FOR OUR NEXT ALBUM WE RE PLANNING SOMETHING VERY SPECIAL: A MUSICAL INTERPRETATION OF AN LSD TRIP. COME ON, GUYS! YOU’RE ALWAYS PROMOTING US AS A PSYCHEDELIC BAND, SO NOW WE’RE GIVING YOU A PSYCHEDELIC RECORD. IT’LL BE THE HAIGHT’S ANSWER TO SGT. PEPPER. ONLY WE’RE GOING TO DO IT IN REAL TIME. A TEN-RECORD SET. AT LEAST!

JUST KIDDING (I THINK).

YOURS, GRATEFUL DEAD

As soon as we’re back home from the tour the pressure is on for new material for the second album. We have an idea, we just don’t have any songs. The contract calls for an album a year for five years. There are men, serious men in white shoes, waiting for product. And I, most recklessly, have told these impatient souls they shall have their vinyl calf before the first full moon in December. Jerry, man, what are we going to do next?

For rock groups the second album is always the crunch. Or maybe it’s the third (I hope). Anyway, by hook or by crook we have to come up with another album. We used up all our old chestnuts on the first album. Plus we are going to wear this material out. By the time the record’s out and in the stores, the band is way tired of it. They’ve already been doing “Silver Threads and Golden Needles” for a year and a half, at least.

Most of the songs the band comes up with are developed in rehearsal and are taken to the stage almost immediately. From the start the Dead have an incredible ability to just be balls out, playing stuff at gigs they’ve only dicked with during practice. I’ll hear a riff at rehearsal and two days later they’re doing it at the Avalon or at the Fillmore. Pretty risky, especially because none of them will ever cop to not knowing the words. They’ll just make up what they can’t remember, and then in the dressing room afterward everybody’s talking at once, going, “Jeez, that was interesting. What was that you were singing out there?”

What the hey, it came out better on Friday than it did on Wednesday, didn’t it? So they try it again Saturday, and on Saturday it’s different (again), but the goddamn thing is actually evolving, just wending its gnarly way toward becoming a Deadsong.

But now, my friends, we must to have many Deadsongs, so epic of Grateful Dead can continue. We must to have — dare I say it? — new material. Never-before-heard, minty stuff. And where is it going to come from? We can’t just count on members of the band periodically forgetting songs and having to make up new stuff onstage, now can we?

Coming up with the words is the hardest part for the Dead, so they start bringing in outside lyricists like Robert Hunter. Hunter’s an old friend of Jerry’s from the Palo Alto days when they used to live in their cars and bum around the folk clubs. A couple of months ago Hunter mailed Jerry a bunch of lyrics from New Mexico, among them some of the verses that will become “Alligator.”

In August 1967 we go up to the architect John Woerneke’s ranch on the Russian River to do a bit of woodshedding. He’s an old friend of the band and he foolishly turns his whole place over to us. Oh well, I rationalize, he’ll have this colorful past to remember after he gets reeled back in by his family’s wealth.

It’s a wonderful place, right down on the river. It is a very hot summer and the river is really cold and as Hemingway used to say it was good. There’s a fleet of canoes and a little pagoda sundeck thing right at the edge of the river. That’s where the equipment is set up, in that little gazebo place, and that’s where the boys rehearse and try to come up with songs. Everybody is crazy on this one. They try out “Alligator” and all these silly tunes that they pull out of their sleeves. They finish up “Alligator” right out of the scene in the river, all these boaters and punters and inner-tubers floating downstream.

Pigpen lies around like an alligator in the shallows and waits for an inner-tubing party of girls to come floating down the Russian. There are a lot of naked ladies floating down that river. He waits patiently, under the water up to his eyeballs. They can’t see his long hair or his tubbiness or any of that. He lays in wait and finally they come around the bend drinking beers and smoking joints and he goes “AAAAAAAAAAAGGH!!!” and scares them half to death.

Mountain Girl and all the chicks make huge meals and we eat outside on the grass and it is very bucolic and scenic and a wonderful place for tripping, but it is also a rough time. We are not getting along all that well up here. It’s too claustrophobic, and there’s nothing else to do. There’s no place for us to go. No way out!

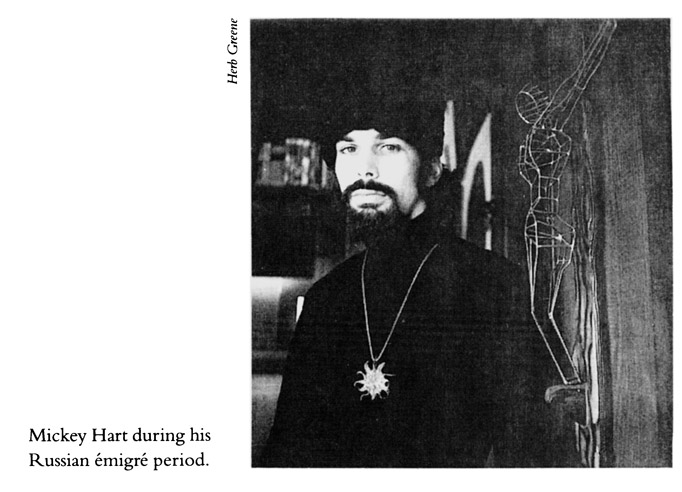

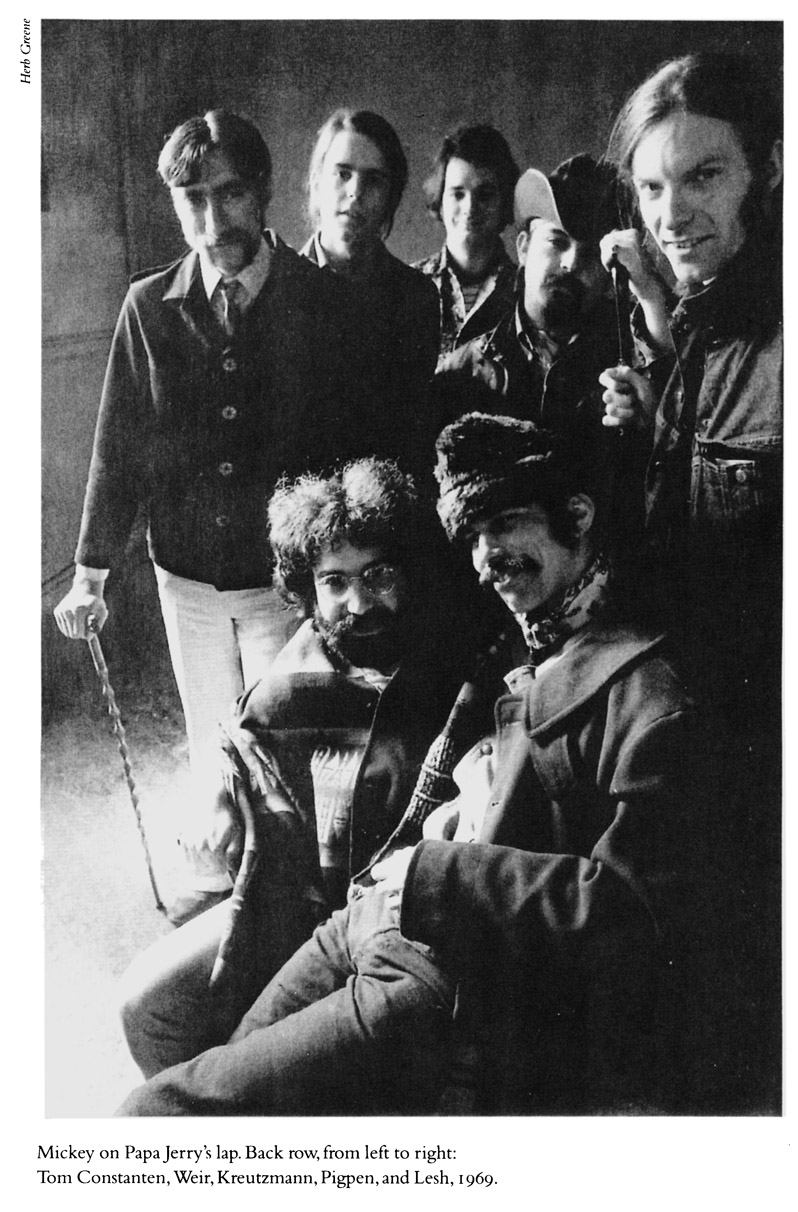

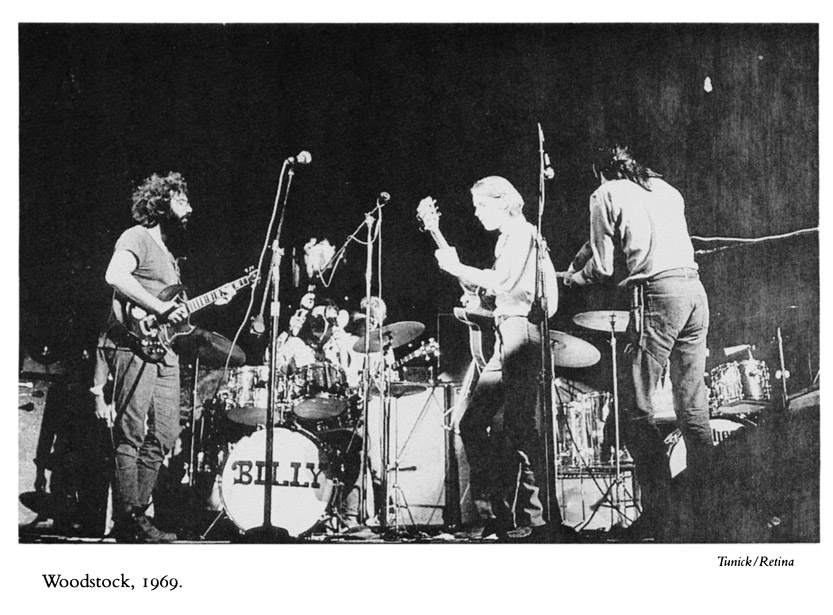

So it’s back to the city. One day we’re playing at the Straight Theater —now known as the Grateful Dead School of the Dance in one of our more strained attempts to circumvent the limitations that the city of San Francisco keeps placing on live music —and a young drummer shows up and asks if he can sit in. Everyone is high on acid and it’s the usual befuddlement. All very casual. Too casual; the band’s sound has begun meandering wildly. We’re a bunch of beatniks who started out drinking red mountain burgundy and smoking pot, and moved on to acid and MDA and DMT and other brain-numbing psychedelics, and by this point we’re dangerously laid back. We’re taking it easy, as usual, when suddenly in roars a B-52 in the person of Mickey Hart. And Mickey turns out to be the shot in the arm we so desperately need. He has that New York energy, a driving force that lights a fuse under us. He’s a “different drummer,” all right. It is strange, given the drive differential, that he gets along so swimmingly with the band. Soon Mickey and Billy Kreutzmann are the tightest of buddies. Their styles of playing are way different —Kreutzmann’s more fluid —but Kreutzmann loves that.

Mickey’s very disciplined. He counts it off, one-two-one-two, whereas Kreutzmann is a downtown swing drummer, a trap drummer essentially, whose heroes are jazz drummers. Mickey, on the other hand, is a stone percussionist. He’s used to playing military marching music and he’s right on the count. He’s a black belt karate guy to boot. He drops the martial arts and loosens up a bit when he joins the Grateful Dead, needless to say.

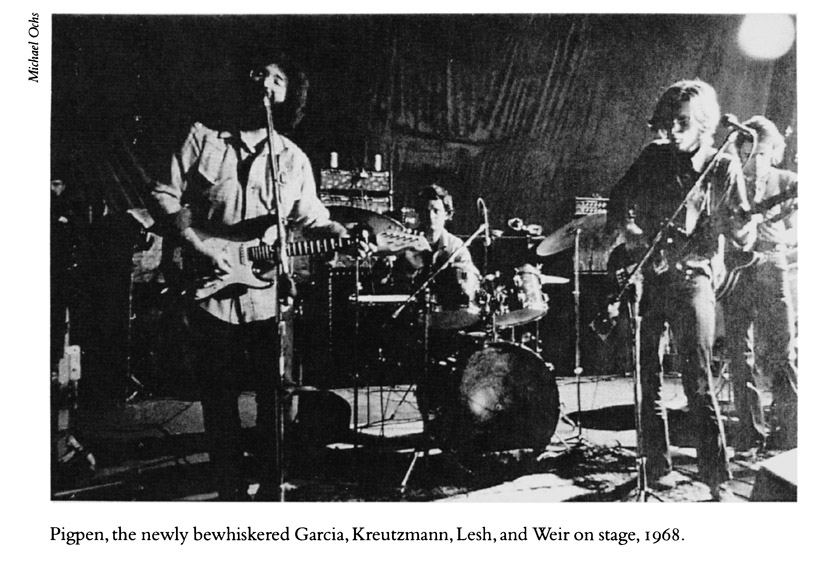

There aren’t many bands that have two drummers, much less two very different drummers playing in different styles. Trust the Dead to go for such a nutty setup! But the Dead desperately need the punch Mickey brings to their sound, in part because of the “Bobby Problem.”

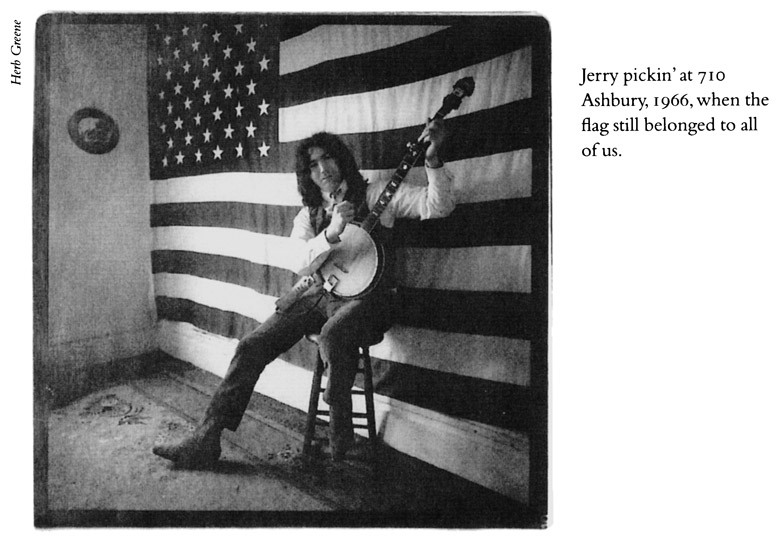

Like Jerry,Bobby Weir started out playing acoustic instruments,but for Jerry the transition from acoustic to electric is an easy one. He has more years of experience than Bobby, plus his playing is more intricate. He is a picker and thus a natural lead guitarist. And from his exposure as a banjo player in jug bands and bluegrass bands he knows how to pick and comp the rhythm at the same time.

But Weir is an acoustic guitar player who has yet to master the electric. He is still trying to play the electric guitar as if it were a Guild hollow body. Garcia is tearing his hair out. His constant refrain after practice is: “Uh, Weir, s’cuse me, but you gotta understand the nature of the beast. It’s an electric guitar.” He keeps saying it, as if maybe Weir just didn’t hear him last time, or hasn’t noticed.

As the rhythm guitar player, Bobby Weir should be the one holding down the groove, but Bobby’s too spaced and unfamiliar with the electric guitar to play straight-ahead attack rhythm. Nobody else in the band is nailing that beat either. Certainly not Pigpen. His Hammond organ is more fill than pulse, and Phil Lesh is playing complicated bass right from the get-go. Rather than keeping the bottom end together, he plays the bass more like a lead instrument!

There’s no bottom anywhere to rely on, no solid rhythm to lean on because Weir is playing late on the beat. More fill than rhythm. Fill is midrange sound, it comes after the attack of the beat, so it translates to the audience as filler. Between Bobby and Pig we are getting mostly midrange fill, which leaves the rest up to Jerry. Which means he can’t play all the leads he wants to play. Instead of being able to fly, he is constantly having to bring the rhythm back to earth. This seriously undermines the Dead sound, because it’s Jerry’s soaring that is the heart of it.

Jerry is overjoyed at Mickey’s arrival. With that extra drummer, the sound gets a lot sharper, and holding down the rhythm is no longer up to Kreutzmann and Garcia. We later find out that Mickey Hart was national drum champion. And his dad was a drum teacher. He knows the most complicated rhythm patterns imaginable and he is always on the money.

Mickey’s drive has the additional side effect of straightening Phil Lesh out. Lesh has been under the illusion that he is “leader of the rhythm section,” but he isn’t funky enough to tack down the beat. Phil wants to wax symphonic on four strings! But he’s got this very basic instrument. (That’s why they call it a bass. . . .) Also, Phil has been taking more lead vocals, which doesn’t exactly help him hold the bottom. Mickey and his energy galvanize the rhythm section and get the bass and the drums together.

Mickey Hart is the first musician that the Grateful Dead ever even considered for the band who doesn’t come from their own backyard. He has a sunny disposition, which makes it easy for him to blend into the group. But laid back, he’s not. He’s intense as hell. Here’s a guy from New York that has been in the military, a drummer in the Air Force Band, middle-class upbringing, middle-class values, impressed with all the wrong things. After he joins the Dead, he hires a limo whenever he visits his grandparents —so when he goes to his old neighborhood everybody will see him getting out of a limousine. He also brings his grandparents, the Tessels, backstage. Grandma Tessel bakes us chocolate chip cookies —they are dynamite cookies and we all gobble them up even though our mouths are dry and our noses are caked.

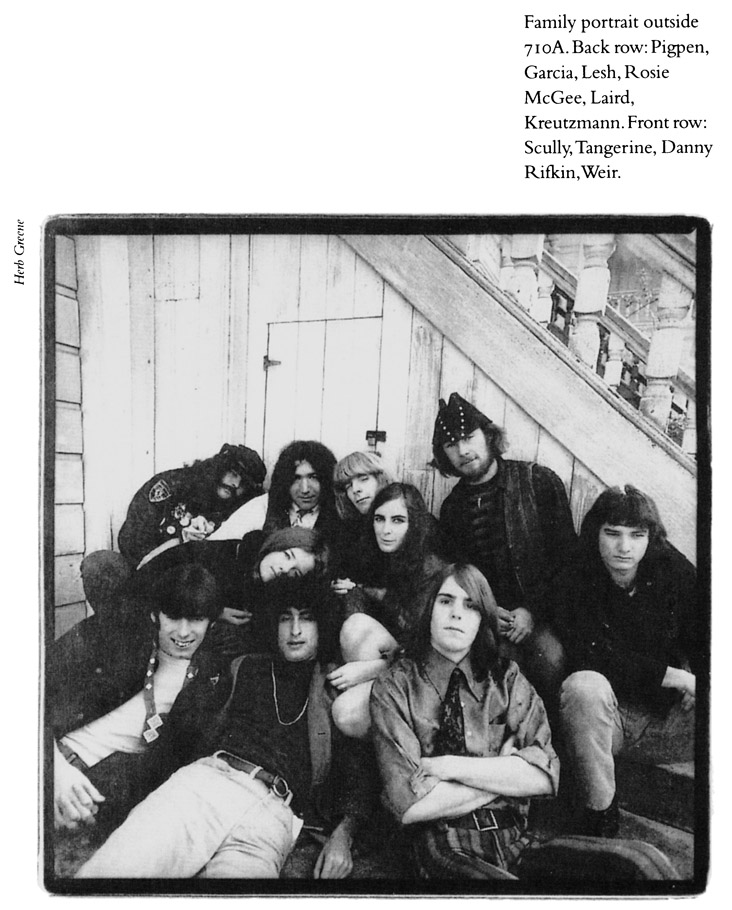

Almost immediately Mickey becomes part of the group and moves in with Phil Lesh and Billy Kreutzmann,just up the street from 710 Ashbury. One day Kreutzmann comes by 710 and I finally ask him something that’s been on my mind.

“Listen, Billy,” I say, “there’s something I’ve got to know. How in the hell do you guys play so perfectly in synch?”

“Hypnotism,” says Billy.

“You’re kidding.”

“No, man, I swear it. Mickey’s been hypnotizing me, that’s how it works.”

“Real hypnosis?” I mean this is a bit unusual even for the Haight. We all wonder about it. A lot. Whether or not this is how Mickey Hart got to be the other drummer. “YOU WILL HIRE ME AS THE EXTRA DRUMMER! YOU WILL MAKE ME THE NEXT DRUMMER OF THE GRATEFUL DEAD!”

Once we have a few songs ready we make our first false start on Anthem in a little studio in L.A., doing some of the basic tracks for the first side. We’re living in a fake Moorish castle in the Hollywood Hills. Thirty-foot living rooms, huge ceilings and white carpets everywhere. Ever so slightly crumbling, another one of those places where we are strictly without furniture. It’s Halloween and we’re right up the street from Bela Lugosi’s house. Jerry loves that —his favorite movie is Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. Lugosi’s house looks like the pyramids, with very imposing walls like those of a mausoleum with hieroglyphics on it. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

While we’re in L.A. we go check out the Maharishi. I think the Airplane got us tickets. As Jerry, Mountain Girl, Weir, and I go in, there are dozens of devotees swarming around, wearing little knee pads so they can crawl around in a perpetual devotional mode.

“Oh yes,” they say, “his holiness will be with you shortly.” He’s a sweet old guy, a bearded swami straight out of an R. Crumb cartoon. And then he says, “I must tell you something, children. . . .”We are all breathless, awaiting the sacred wisdom, and he says: “You must not be calling yourselves ’Grateful Dead.’ You must call yourselves ’Eternal Living’! And you must wear silken pajamas.” I’m serious! He gives us each our mantra —mine sounds like a phone ringing.

We try. Mountain Girl’s really into it: “You guys got your mantras together?” she asks us every morning. She even gets Jerry to go back for a second session. He hates it, but Mountain Girl is tenacious. For the next couple of weeks you can hear Mountain Girl saying to Jerry, “I got my little mantra, and it works. C’mon, if Ringo can do it, you can do it. Anybody can.”

And Jerry’s going, “But what would Madame Blavatsky say?”

After a few weeks we decide to call it quits with L.A. We have at least enough control to say we want to do our album in New York. We want New York because we’re playing at the something-a-go-go that later becomes the Cheetah, and we’re also looking for a studio with more than four tracks. The record company allows us to go because they want to get the record out, but they make the proviso that Dave Hassinger has to be the producer again.

We camp out in some falsetto group’s mansion in suburban New Jersey,Jay and the Americans, I think, not too far from the tunnels and the bridges. It’s on a tree-lined street and set back —and empty. Another one of those houses with no furniture where I have to rent beds for everyone. We commute into the city every day to record.

Relations with Dave deteriorate fast. He didn’t want to go to New York in the first place. We’re about two-thirds of the way through the material that comprises Side One —all that studio stuff —but the studio cuts aren’t making it. Hassinger is becoming more and more anxious because we are spending huge amounts of time doing things like stuffing quarters and feathers into the sound box of the grand piano to get those seldom-achieved sound effects.

Naturally much of this psychosonic experimentation looks to Hassinger like a big waste of time. We’re at Century Sound less than a week when things start to fall apart. Ironically, it is Hassinger’s little buddy, Bobby Weir, who provokes the violent reaction. As the band becomes less and less reasonable, Hassinger has come to see Bobby as the only one in his corner. Bobby is trying his best to be polite and isn’t (currently) smoking dope. Still, even reformed acid-eaters have strange thoughts.

“Born Cross-Eyed” is Weir’s first original song and he has some very specific ideas. But he doesn’t quite have the vocabulary to convey the ineffable idea he has in his head and whille listening to the playback says to Hassinger, “I don’t like the sound of that.”

Hassinger’s jaw drops open. “What are you talking about? There’s nothing going on there! It’s just air. Dead air or something.”

To which Weir answers: “Well, that’s what I want. I want the sound of, uh, heavy air, only more of it.”

“What the hell does ’heavy air’ mean, anyway?”

“It doesn’t mean anything, Dave. It means whatever you want it to mean. Uh, y’know, summer air with linnets’ wings. Like, a lot of bugs and the light filtering through.”

This sound-of-heavy-air business is the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Hassinger goes berserk. Mentally and physically falls apart before our eyes and becomes a mass of twitching enraged protoplasm. The guy loses it. He becomes speechless, literally unable to speak. The Dead can do that to people. He’s ahead of his time, one of the early casualties of culture shock. The guys running the record companies are a generation older than us and from an earlier school of making records. It isn’t just Dave Hassinger, it is us trying to mesh with that straighter, earlier generation world of how things are done.

The heavy-air effect is achieved by splicing a three-second strip of paper —called an “island” —in the tape, which in one enveloping “ooooooooosh” inhales the sound of a sultry August night.

After Hassinger goes belly up the whole thing is dumped in our lap, which is the way we want it anyway. We tell Warner Brothers: “Don’t send us any more guys in golf shoes.” It is time to move the Neanderthal recording industry into the next era. Dan Healy’s been taking care of our equipment, and he is an electronic wizard who speaks our language and the studio’s language, so he is the natural choice to take over. The only person really who might be able to deal with our overwhelming dilemmas. He’s not simply replacing somebody who went ballistic, he’s also replacing the way people go about making records.

Of course, who’s going to do what on the album is always a bit tricky when you’re dealing with a group of independent-minded people. Especially so with the Dead who have, at this point, four potential lead singers: Garcia, Weir, Lesh, and Pigpen. Juggling all this is a delicate operation. And don’t forget the drummers who don’t sing but want their piece of the pie, too.

It’s like a family anywhere. Someone is always feeling left out: “Hey, I got ideas, too!” Someone else is saying in a whiny voice: “How many songs does Weir have on this album?” And I’m like Mother Goose ladling out tracks in a singsong voice: the first track is Jerry’s, the next is Weir’s, the next is Phil’s, the next is Jerry’s, the next is Weir’s, the next. . .

It’s during the making of Anthem that Tom Constanten gets involved with the band. He’s a music school friend of Phil’s and in November, Tom starts playing piano on some of the tracks. In those days you ferreted out freaks in whatever area you could find them. But Tom is an oddity even for the Grateful Dead.

He has a ridiculous Napoleon Bonaparte haircut —with kiss-curl pulled down and trimmed ever so carefully across, wearing a four-button jacket buttoned all the way up with a new immaculate white collar. The rest of us are all shaggy, growing beards, wearing ripped T-shirts —clearly the man has no sense of appropriate studio attire.

He has an erudite wit, which doesn’t always chime with the prevailing acidic sense of humor of the Dead family. He perhaps takes things more seriously than we do, especially his new “religion,” Scientology. Probably a reformed speed freak like Monsieur con brio Lesh.

Anthem of the Sun evolves into a picture book of images that meanders all the way through a trip and comes out the other side. In other words, you can’t make head or tail of it, and that’s sort of the point.

And what would a trip be without sound effects? In the section after Jerry’s song “That’s It for the Other One,”we use UFO landing sounds and other strange noises. It’s a forerunner of the space jam.And a lot of this stuff —just plain guitar weirdness —the Dead do live. We have this box called the Insect Fear Device, that you can plug the guitars or microphones into and play or sing through it and it makes all kinds of unearthly sounds.

The prepared piano is pretty much Tom Constanten. The term “prepared piano” means doing things to the piano, but it is used in its widest sense here. Stuffing things in it, partially damping strings, causing strings to rattle against things. Tom puts quarters and half dollars and shit in between the strings or weaves cellophane through the strings and it makes really eerie cracking sounds. A grand piano is an amazing contraption. You can use a grand piano to actually launch stuff. There’s also a little prepared comb on this record. Pigpen is wicked on cellophane-and-comb combo. He plays a bit of jaw harp and all those little sort of trinkets that you horse around with.

And then there’s the sounds of destruction. Abusing and misusing equipment to come up with those strange and obscure noises. The Dead go through a whole period of demolishing microphones and seeing what sounds you can get ’em to make as they die. Dropping them, closing them in a door, that type of thing. Random destruction of the sacred cows of our parents’ generation. Our parents came out of the Depression and their motto was: “Take very good care of this stuff, you may never get another one.”

We were all raised with those pieties, so trashing your shoes or a piece of equipment or trashing your instrument is something that we all have to get out of our system. It’s the same as getting away with saying “fuck” on the radio, which we are doing a lot. Garcia gets sixteen “fucks” into one interview in Philadelphia.

It is a fragmented process because we’re jumping from studio to studio. Jerry doesn’t feel that we can do a good mix at Century Sound and prevails on me to call Paul Simon and find out if we could use one of the CBS studios. So that’s what we do, but all these scenes are unionized to the max and in the middle of mixing down “Cryptical Envelopment” Jerry just forgets and reaches over and touches a knob and bang! we’re outta there. We get thrown out of a couple of other studios for smoking grass —in quest of that elusive sound we hear all the time onstage. But we aren’t getting it on tape. The band are looking for that live sound in the studio, but the technology just isn’t up to it. Neither is the band. They’re used to playing together. We can’t isolate the drums so they don’t bleed into the microphones on the other instruments. To the Dead this business of listening to a drum track on headphones while playing guitar is downright creepy. And it’s at this point that it occurs to us, why don’t we use live tapes that already have that spontaneous feel?

The idea of pressing on with a studio album is not that appealing because the Dead are and always will be a live performance band and don’t flourish in a studio environment. The gigs are so much more fun and yield so much more interesting music. Trying to duplicate our sound in the studio seems futile.

The stigma against live recordings is entirely a record company thing, and needless to say it comes down to the scaly business of money. Since the songs in live concerts are usually rerecordings of material for the most part already on studio albums, there isn’t a new set of songs to scoop the publishing gravy off of. And because it doesn’t go through the normal channels, the producers and A&R guys don’t get a cut either.

Anthem in the end is part live/part studio, but we tell Warner Brothers it’s a studio album. This is possible because everything is so far out of whack that by the time it gets down to the fine point of what is actually on the album, it is ten light-years beyond the question itself. In the meantime we resolve to take recording equipment with us on our next tour and begin packing stuff up to head back to the West Coast.

Back home we find we can’t take the Haight anymore. There are tour groups passing by all the time. The Gray Line buses stop right infront of the house. And everybody who comes to the Haight has the idea that they can go and talk to Jerry or Janis anytime they like. Casual intimacy was one of the great things about the Haight, but once the population multiplies it is lost. You can’t be intimate with fifty thousand people. Most visitors to 710 are polite, sincere, and stoned, but eventually it does get to us. Even us hippies can’t be nice to everyone! The strain is so great that things are actually becoming tense in our very laid-back household.

Being Hippie Central does have its perks. People like Neil Young and David Crosby come up and visit us. Even Sir George Harrison comes and spends the weekend, and I end up showing him around the town. We are smoking as we go. Smoking, smoking, smoking. He can’t believe people openly rolling joints on Haight Street, people throwing joints at him. English visitors are always boggled by the whole pot scene. And he loves the fact that he can walk down Haight Street more or less without hassle. People just hand him joints and maybe walk along and chat for a minute and then let him go his own way.

On Divisadero we run into a couple of Hell’s Angels, Tumbleweed and Pete. Wow! Real sweaty, savage Hell’s Angels. The terror of the West. He’s impressed, all right. They’re impressed, too.

“Fuckin’ George Harrison, man!” Somehow in the heat of the moment George invites them to come and stay with him “whenever you’re in London, man.” You know, at George’s house! Now in England, this sort of invitation is taken for what it is: perfunctory politeness. Besides, he must have thought, when are two Hell’s Angels ever going to show up at Savile Row? But this is California, baby! The West — where a man’s word is a man’s word. . . .

“Well, Jesus, George, that’s real decent of you. Real decent. We’ve been planning a trip to check out swingin’ London, haven’t we, Pete?”

“Yeah, take the tour of the Triumph motorcycle factory and all. Hell, we’ll bring the Harleys, it’ll be a hell of a time.” Whereupon George proceeds to hand them . . .his card. A bit formal, I think, but the boys fall on it as if it were a fresh kilo of dope. They hand it to me—to sniff, I presume —and I notice it’s an Apple Records card. Oh well, I guess he’s not actually going to give them his home number, now is he? I mean, what if these guys actually show up?

We continue on down Haight Street. Kids are lying on the side-walk, dogs in kerchiefs are running up and down the street, people are panhandling. It’s so crowded in spots it’s hard to walk. George suddenly seems alarmed.

“How do the Dead deal with this?” I tell him we’re planning to bail out sometime soon, maybe move out to Marin.

The bus tours and crowds aren’t the only drawback to our becoming Big Stars in the Haight. It’s October 2, 1967, and Jerry and Mountain Girl have scored a big block of Acapulco Gold wrapped in beautiful blue cellophane. It’s the happiest weed imaginable. Hallucinatory pot where you see little halos around everything. We also have some really second-rate Cannabis arnericanus out on the table in the house. Real stringy with lots of stems and seeds. Jerry and Mountain Girl are sitting in the pantry with the colander out on the counter and the shoe boxes, cleaning this Mt. Shasta weed and rolling some doobies when there’s a knock on the door and, hey, it’s Hermit from the Pranksters.

“Listen, I’m out of grass and I thought maybe you guys . . .” Now, this is a little odd because Hermit hasn’t come by 710 before now, even to visit. But M.G. thinks, what the hell. “Hey, Hermit, sure. Help yourself to a couple of joints out of the shitweed on the kitchen table.” Which he does and then she gives him a baggie full of grass. But instead of going off whence he came and getting high, he starts asking what Mountain Girl is going to do during the day, like he’s going to hang out, which she definitely doesn’t want to encourage and anyway she’s going over to a store in Sausalito to look at fabric and buy some ribbons. She’s making a stage shirt for Jerry.

Right after Jerry and Mountain Girl leave, Hermit skips down to the corner and gives the bag to the cops and they bust 710. When Jerry and M.G. get back a couple of hours later they are about to set foot on the steps of 710 when Brian Rohan’s girlfriend, Marilyn, from across the street comes to her window and begins hollering to them, “Hey, you guys! Come on up! We’re waiting for you up here.” She lives right above the offices of HALO, the Haight-Ashbury Legal Organization. As M.G. and Jerry look out Marilyn’s window they see the heat, a lot of guys in suits pouring out the front door of 710. They used Hermit to come in and set up Mountain Girl and the rest of us.

Shortly afterward I show up. I’ve been out of town and when I get back to the house everything is strangely quiet. It’s already a bit weird that there’s nobody hanging out on the front steps and when I see all the news vans I get a little pissed off: “Hey, who’s havin’ a press conference without telling me?”

I come storming up the steps and the door is locked. That is also a little strange because we never even shut that door unless it’s freezing out, on account of people forgetting their keys. When I look into the office through the window and I can’t see anybody, I immediately know there’s trouble. I begin banging on the door: “Come on, you guys, open up!” The door flies open and a cop reaches out, grabs me by the shoulder, and yanks me inside the vestibule and says, “You live here?” and I go, “Uh, sort of.”

“You’re under arrest,” and he reads me my Miranda rights. They’ve got Florence, Pigpen, Bobby, and Sue Swanson. Danny and Bob Matthews and I are already in cuffs and they take us all downtown.

Nobody really thinks we’re going to be sent to San Quentin. We know we aren’t even going to spend the night in jail. They put us in a holding cell for a few hours and ask us lots of questions. There’s nobody in the slammer but us and we just sit there until Brian Rohan bails us out.

When we get back to the house we see to our amazement that the fuzz haven’t found the kilo of dope in the pantry. How is this possible? The last view I had of it, it was sitting open on the shelf right there among the plates and dishes with the weed falling out of it, and the blue wrapping all ripped and hanging down. At eye level. It’s inconceivable they could have missed it. We are very suspicious, and immediately think they’re planning to come back and bust us again. Somebody takes it out of the house and hides it, and we never find any of it again. It’s like they say: They’ll never legalize marijuana because no one can find the petition!

Since the Dead have no intention of forsaking the demon weed or anything else for that matter, they decide they’re just gonna have to think outlaw, and they keep that outlaw thing going forever. Especially Garcia. It’s very important to him. For him it’s a god-given American value. He says, “We’re a nation of outlaws. A good outlaw makes a new law, makes it okay to do what he’s doing.”

As we’re getting to the end of our rope in the Haight-Ashbury, there is a definite shift from the psychedelics and experimental drugs to the hard-drive drugs. Coke is becoming common, and recently speed has been making quite a spectacular comeback in Hippie City. A lot of the momentum of the Haight had to do with methamphetamine; it’s something that we all experienced. Phil has been on speed for years, and Garcia and Bob Hunter could definitely have been called speed freaks during their coffeehouse days in Palo Alto. They lived on meth, grass, and cheap red wine.

When hard drugs come to town rumors fly around that some of us are doing smack. When Mountain Girl hears of this she has everybody on inspection. Weir,Lesh, Hart. At Winterland she catches up with me and nails me up against one of those vomitory ramps, slams me up against the wall, and rolls up my sleeve to see if I’ve been using a needle. Doesn’t ask, just does it. I’m not pissed off that she’s doing it, but I’m pissed off that she could believe that I’m using. I am proud to show her my arms. “Look, Mom, no tracks!” She scrutinizes me thoroughly, her eyes an inch from my skin. When the examination is over, there’s no apology or embarrassment about the search. But then this is Mountain Girl. All you get is a clean bdl of health: “Okay, you’re clean. Good, I was worried.” And you walk away very pleased with yourself.

But Mountain Girl has definitely picked up the right vibes. Hard drugs are humming through the scene. None of us are yet enough aware of their effects to be able to tell who is on what, and anyway everybody is tolerant of unforeseen mood swings even if we can’t put a finger on what’s causing them.

One afternoon I’m kibitzing with Peter Coyote and Emmett Grogan of the Diggers in the office at 710. There’s nothing going on, the phone ain’t ringing, and Peter and Emmett are getting antsy. Let’s go upstairs, they say. I think we’re going to smoke a joint. So we go upstairs and Emmett immediately starts cooking heroin in a spoon and I think, Ooohhhh, man, he’s going to shoot up, which just makes me queasy, but he’s enthusiastic about the stuff. He’s raving about it. “Gotta try this shit,Rock! How do you know you don’t want it if you never tried it?”

Emmett says it’s really cool, so of course I decide to try it. Story of my life! He ties me off and shoots me up and when he takes the tie off I feel this incredible hot rush and the next thing I know Pigpen’s in the room screaming and el ling at me. I guess I must’ve passed out. I am sweating all over, clammy and cold as a bitch, and Pigpen is just livid. He’s screaming, “What the fuck did you do to him? I’m going to go call an ambulance.”

Peter calms him down. “No, no, no, we don’t want to call anybody, for chrissakes! He’ll be okay, he’ll be okay.” I wake up with Grogan slapping my face and Pigpen’s on top of him, ready to kick his kidneys in. And that’s my first brush with smack. Scared me to death.

Drug-dealing had always been an easygoing, amateur affair in the Haight. You bought a few kilos of grass and sold ounces to your friends. But shortly after the Summer of Love a more sinister species of dealer moves in. It doesn’t take long for the career criminal element to figure out that these hippie kids have money and want drugs. Most of these kids don’t have a clue what pot is and by the end of that summer oregano is going for thirty-five dollars a bag, aspirins are being sold as LSD for five dollars a hit. Little hippie kids catching a buzz off Bayer. And in no time at all drug turfs spring up. When they find Super Spade’s body out in Marin County thrown off a cliff, we know we’re in trouble. Super Spade was a classic Haight-Ashbury dealer, pot and acid is what he dealt. It was a Mafia hit. Up until now there wasn’t serious money being made — except by chemists like Owsley. Mobsters didn’t know where to buy LSD and even if they could find it they didn’t know how to distribute it, but they soon found a way.

Crime comes in with a vengeance. Of the old hippie dealers only Goldfinger is left, up against this enormous group of gangsters who are trying to muscle in on Haight-Ashbury.

By the end of ’67 things are beginning to come apart very rapidly. It’s become a runaway train. We march in the Death of Hippie parade. It’s a Mime Troupe–inspired event designed to catch the attention of the news media and send a message that will hopefully say to kids thinking of coming to the Haight: “Stay where you are, it’s getting worse here by the moment. We can’t feed you, there’s no housing, there’s bad drugs.” Staging symbolic events is a Mime Troupe specialty, and in this we support them wholeheartedly. Not that it does a lot of good. The scene in the Haight will go on for a while, but after the Summer of Love invasion we just want the party to end. Turn out the lights and everybody go home.

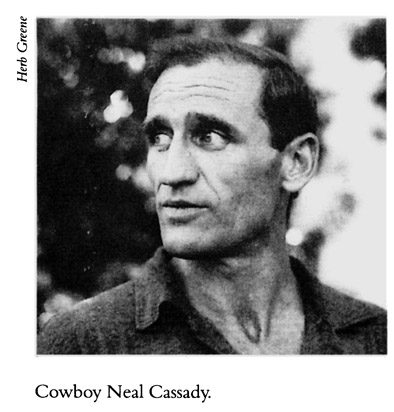

Thanksgiving 1967 feels like a last hurrah. The Airplane come, and the Charlatans, and Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley and Neal Cassady, our genius loci, presiding over all. We open all the big sliding doors that separate the different rooms — the front room from the dining room, the dining room from the back room, which is Pigpen’s room. We finally get to see Pig’s room. He has to clean up his room and make his bed and do all the things that he hates to do, because we are incorporating his room into the festivities.

We put together every table in the house, take doors off the hinges to make tables, and then cover the whole thing with motley tablecloths. We have tables winding through from the front of the house to the back, all on different levels. It goes up and down with the height of the different tables. People are sitting on easy chairs or towering over the tables on stools. Everybody brings something to this wonderful Thanksgiving dinner, their favorite thing or the best thing that they make.

The dinner is e1egant:pies and soup, rice and all kinds of exotic side dishes, from American Indian recipes and Zen macrobiotic to traditional American turkey and stuffing and sweet potatoes and gravy. Everybody eats themselves silly except for Neal Cassady. Aside from sixteen diet pills, he doesn’t eat a thing. For him those Desoxyn are the best brown meat, white meat, stuffing, mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes and pie and gravy and cranberry sauce imaginable.

Le tout rock ‘n’ roll of San Francisco comes. It’s probably the first time a lot of us have a celebration like this that isn’t with our families. It’s one of those moments where we realize that we’re making our own kind of family here.

Cassady never sits down. He’s up on the table, doing a little dance from corner to corner, rapping out his own Dada digest of the news. A futurist collage of an article on Vietnam and then on to movie reviews or 5ome book review and then back to how the folks at the White House are planning to celebrate Thanksgiving. This is our dinner music. Jerry loves it because you can talk over it or under it, relate to it or ignore it. Jerry and Phil, who are both well read,listen to it like instantaneous poetry and toss lines back to him and feed the frenzy. Cutup conversations pieced together out of the dross and everyday surrealism of American culture, a Mahabharata of gossip, mental mumbling, song lyrics, weather reports, and menus. You can see why Kerouac and Kesey loved him so much. The guy was a brilliant writer who never stopped long enough to write it down.

But under the camaraderie and high spirits runs a strain of melancholy. We know something we believed in with all our hearts has ended. The Haight is going all to hell and shortly the Dead farmly is going to be splitting up. We’re never all going to live together again. We are being cast out of Eden. Time to roll another joint.