Chapter 13

Openness

“I’ve Been Hiding Behind a Mask”

A mask is a false face—a feeling projected to others that’s different from what you’re really feeling. Some masks are appropriate; others are inappropriate. Masks may protect you from emotional pain you feel or fear, but wearing masks takes a great deal of emotional energy. Masks distance you emotionally from others, keeping you from building intimate relationships. When you remove your mask appropriately, you find intimacy, rather than emotional pain.

After my divorce, looking for ways to meet new people, I took a small part in a little theater production. One night at rehearsal, I suddenly realized that’s what I’d been doing in my marriage: reciting lines. I wasn’t myself; I was a character in a romantic comedy-tragedy.

—Scott

At this point in our climb, most of us have learned a lot about ourselves and our former love relationships. You probably have a good idea of what happened, and we hope you’re starting to think about how you’ll avoid similar mistakes in the future.

One key element in successful love relationships is openness. Were you really honest with your partner? Are you really even honest with yourself? Or do you often hide behind an “everything is okay” mask?

Masks and Openness

All of us wear masks at times. Sometimes you just don’t want others to know what you’re feeling, and a “mask” is a convenient way to hide what’s going on inside—a protective shield. So the mask projects a different attitude or feeling on the surface, protecting you from the pain underneath. The pain may be fear of rejection, fear of somebody not liking you, fear of feeling inadequate, or maybe just a feeling that nobody really cares.

Young children don’t wear masks as adults do—that’s one of the reasons it’s enjoyable and delightful to be with them. We develop our masks as we mature and become “socialized.” It’s not a conscious effort to deceive; the idea is simply that the masks will help us to interact with people more effectively.

However, some masks are not productive in helping us to connect with others. Instead, they keep us at a safe emotional distance from others. Openness, after all, can be pretty scary at times.

What Color Is Your Mask?

What are some examples of the masks we’re talking about?

There are some people who, as you become emotionally close to them, immediately start making jokes and cracking humor—the humor mask.

A similar mask is the Barbie-doll face. Whenever you start getting real with such a person and start talking about something important, you immediately see the happy, smiling, unchanging face that looks like a Barbie doll.

Many people going through divorce put on the strength mask. They project an image that says, “I’m so strong”—in control at all times and never showing any weakness—but underneath lies the real turmoil of confusion and helplessness.

Like nearly all divorced people, Connie had been close to the fire of emotional intimacy. When she was married to Chris, he made her feel really warm. Then she was burned by the fire, and she grew afraid to become emotionally close to warmth from another person again. Now she distances other people emotionally in all kinds of sophisticated ways. Her “don’t mess with me” angry mask has a reputation for miles around; it’s very effective in keeping others at arm’s length.

Who’s Masking What from Whom?

Some masks are not very productive. In wearing them, we fight against the very things we long for: closeness, intimacy, a feeling of being safe with another person. But because we’ve been hurt, we’re also afraid of that same intimacy and closeness.

Marian projected a mask and thought she was fooling people; that they didn’t know what she was really feeling. She learned, however, that not only did others see through the mask, they saw her more clearly than she saw herself. That’s one of the strange things about masks: we often fool ourselves more than we fool other people. The mask Marian thought nobody could see through allowed others to know—better than she knew herself—the pain she was feeling underneath.

A mask may keep you from getting to know yourself, rather than keeping somebody else from getting to know you. When you wear one, you are actually denying yourself your own hurt. It’s kind of like the ostrich: with his head in the sand, he thinks no one can see him just because he can’t see them.

Masks Can Be a Burden

Sometimes we invest a great deal of emotional energy in wearing our masks.

You’re carrying around a great big burden all the time by trying to act the way you think you “should” act instead of just being yourself. The emotional energy that is put into carrying a mask is sometimes almost overwhelming. You spend more energy carrying the mask than you do learning about yourself, achieving personal growth, or doing anything more productive.

Think about how lonely it is behind a really big, thick mask. A person is more or less living in his or her own world, and there is no one else who really knows and understands that person deep underneath the big mask. Often the more lonely you feel, the more of a mask you create around that loneliness. There seems to be a direct connection between the amount of loneliness you feel and the thickness of the mask you’re wearing.

Anybody who has been carrying around a really heavy mask and then takes it off—in counseling or in sharing and talking with a friend—discovers a great feeling of freedom after unloading the burden. It leaves a lot more energy to do other things in life.

Jeff started wearing a mask as a child. He learned early that he had to exhibit certain “acceptable” behaviors in order to get the love or the strokes or the attention that he needed. He learned to take care of other people when he really wanted to be taken care of himself. He learned to excel in school, even though he really didn’t care whether he got A’s or not. He learned to keep all his feelings inside rather than open up and share himself with others. Jeff grew up with the idea that love was not related to being himself. It came to him when he wore his “good boy” mask. He sure learned well not to value openness.

We develop most masks because we have not felt loved unconditionally just for being ourselves.

“Let’s Do Lunch: My Mask Will Call Your Mask”

Imagine somebody trying to kiss you when you have a mask on. That’s a good image for how hard it is to get close to another person when either of you is wearing a mask. It gives an idea of what a mask does for the communication between you and another person. Think of all the indirect and devious messages that are sent because of our masks. So much for openness!

There are appropriate masks and inappropriate masks, of course. An appropriate mask is one that you wear at work while dealing with other people. You project the feeling of efficiency, of competence, of “I’m here to serve you”—an evenness and a calmness that makes your work with other people more effective. But when you get off work and go home to be with a friend or a loved one, the same mask becomes inappropriate. It emotionally distances you from your partner, prevents straight communication, kills openness, and doesn’t allow either of you to be yourselves. That could be appropriate when you need time just for yourself, but it’s tough on intimacy!

A Matter of Choice

A mask that you choose to wear is probably an appropriate mask, but the mask that chooses you is probably inappropriate. It chooses you because you are not free to expose the feelings that are underneath. And in that sense, the mask controls you. Many times, you are not aware that you’re wearing a mask that controls you.

Are You Ready to Take Off Your Mask?

How does one decide to take off a mask? At some time during the divorce process, it becomes appropriate to take off some of the masks you’ve been wearing—to try openness instead. Is that time now?

What would happen if you took your mask off? Why not try it with some safe friends? Take off a mask and see how many times you find acceptance from those friends rather than the rejection you expected. See how many times you become closer to somebody rather than being hurt. See how many times you feel freer than you felt before.

Here’s an example of how to take off a mask with a friend you can trust. You might say something such as this: “You know, there have been times when I’ve not been very honest with you. When you come close to me, I become a joker. The ‘joker mask’ is a defense I use to protect myself from getting hurt. When I’m afraid or feel that I’m about to get hurt, I start making jokes. When I make jokes at inappropriate times, it keeps me from knowing you and you from knowing me. I want you to know about my mask. When I tell you about it, it destroys some of the power of the mask. I’m trying to take off the mask a bit by sharing this with you.” (Later in this chapter, we’ll give you an exercise in “lifting the mask.”)

Some friends may hurt you when you take the mask off. Those people are not able to handle the feelings you’ve been covering up with the mask. But if you had your choice, which would you choose? To continue to wear the mask and not get to know that person? Or to take off the mask, be open, and risk being hurt or rejected? If you are at a point emotionally where you can think ahead to a possible love relationship in the future, what kind of a relationship would you like to have? One that would include openness, intimacy, and trust? Or one in which both of you wear masks of one kind or another? You do have the choice!

If you are wearing a mask to cover up pain, then part of removing the mask must be to deal with that pain. As counselors, we prefer to help our clients try to get in touch with the pain behind the mask and to express and verbalize it.

When Sharon was going through a divorce, she was trying to be the strong person, always in control. Her therapist encouraged her to talk about the pain and confusion she was feeling underneath, and she did, hesitantly. She learned that maybe it is appropriate to be confused when going through a confusing situation and that taking down the mask and dealing with that confusion is productive. It took her several sessions in therapy to fully acknowledge her pain and to build some constructive coping strategies that allowed her to keep the mask off.

Many who have been hurt at the end of a love relationship put on more masks than they were wearing before. Part of climbing this mountain we’ve been traveling is learning to take off some of the masks you may have put on to cover the pain of ending your love relationship.

Your Self Behind the Mask

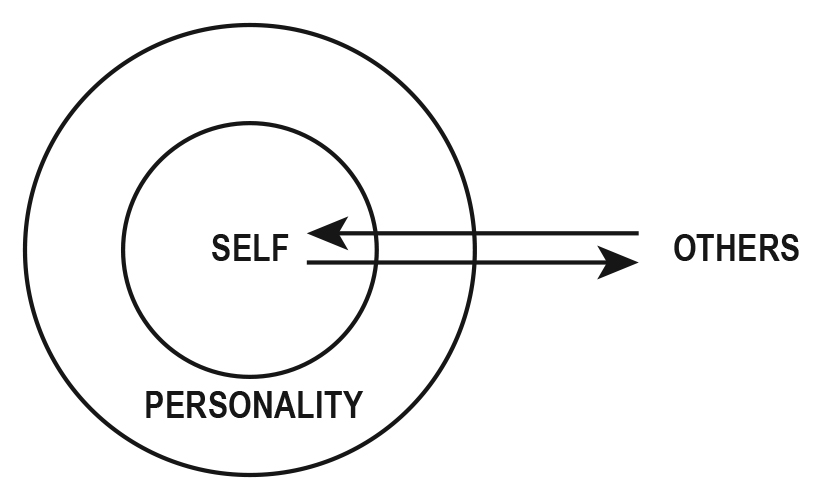

We all have a distinct self inside us—not yourself, but your self—the real person deep down inside. We all develop our personalities—the face we show to the rest of the world—around this essence of self. We communicate outward from that self down inside, through the personality, to the people around us. Ideally, the communication is two-way, from one person’s self to another’s.

When you develop a thick shell or facade to “protect” your inner self, your communication is blocked by that mask. Instead of messages going from self to other back to self, they go from mask to other back to mask. (Of course, the other person may be wearing a mask also!)

In this situation, your self is not really involved in the communication. If you keep the mask on, your inner self becomes starved and never sees the sunshine and never finds anything that will help it grow. Your inner self becomes smaller—or at least less influential—until it is so small that you may not even be able to find your own identity. Meanwhile, the shell around you grows thicker and harder all the time.

There’s another variation on this theme: you may mask certain areas of your personality but not others. In the diagram below, there are barriers to parts of your personality that prevent communication through them, but there are other parts of your personality through which you do communicate to other people.

To take another example from Bruce’s probation officer days, he found some juveniles very easy to work with, while others were very defensive around him. After a while, he noticed a pattern: A juvenile who was easy to work with usually had a good relationship with his father. He was able to communicate well with his probation officer, who was somewhat of a father figure. But a young man who felt uncomfortable relating to Bruce probably also was uncomfortable with his father. He had developed a powerful protective mask that prevented communication between his inner self and adult males in authority. This same juvenile might find it easier to work with a female probation officer, particularly if he had learned to relate well with his mother.

Who Are You?

Do you know yourself? Are you pretty sure of your own identity? Many people use masks because they lack a sense of identity. They can’t be open because they don’t know who they are or what they’re really feeling. They start wearing masks, and the masks begin to get thicker and thicker and the self inside gets even harder to identify. Pretty soon, these people have lost touch with their identities completely. They lack the support and encouragement needed for their identities to grow.

If you want to take off your masks, then you need to get as many feelings as possible out into the open. When you share things about yourself that you have not shared before, you are actually taking down a mask. And when you ask for feedback from other people, you often find out things about yourself that you did not know before, and this, too, takes down one of the masks that you have used to keep from knowing your self.

To get rid of some of the inappropriate and unproductive masks that you are carrying around, begin to open yourself up as much as possible to other people. Develop some relationships with other people that have a great deal of open, meaningful communication (not just talking about yourself endlessly). These connections with others will help you take off the masks, allow your inner self to grow, and place all your relationships on a foundation of honesty and openness—with yourself and with those you care about.

There are many people whose little boy or little girl inside is extremely frightened and fearful of coming out. If you’re experiencing that kind of fear, you’ll find it helpful to enter into a professional counseling relationship. Counseling is a safe place to let your scared little boy or girl out—to get open with yourself.

Homework to Help You Move from Masks to Openness

- Sit down and make a list of all of the masks you wear. Examine these masks and determine which are appropriate and which are inappropriate. Identify the masks that you would like to take off because they are not serving you well.

- Focus deep inside yourself and try to get in touch with your feelings. See if you can locate the fear or pain underneath the masks you wear. Why is it important to protect yourself from intimacy with others? The masks are probably hiding fear of some sort. Look at those fears and see if they are rational or if they are perhaps fears you developed from interacting with other people in unproductive ways.

- Find a friend or a group of friends with whom you feel safe—friends you can trust. Describe this exercise to them and let them know that you are going to try to share some of your masks with them. Explain that by revealing your mask, it will not have the same power over you as it did before. Share with these friends some of the fears that have kept you from being open and honest and intimate with others. Ask the other people to do the same thing with you. Open, meaningful communication between you and your friends will help you get free from the masks you’ve been carrying around and will help you recover some of the emotional energy they’ve required.

The Masks of Children

How open and honest are you with your children? Have you shared the important things happening in your relationship that directly affect them? How did you tell your children when you were ready to separate from your partner? How consistent have you been with them? Can they depend upon you to do what you say you will? In short, can they trust you?

In one workshop we conducted for children of divorce, a thirteen-year-old girl was asked what kind of an animal she felt like. “That’s easy,” she responded. “When I’m with my dad, I am one person. When I’m with my mom, I’m another person. I try to please both of them so they won’t be upset. So I’m a chameleon.”

It is so hard for us to really listen to our children when we are caught up in our own pain. We can easily be hurt and upset by their comments. No wonder they walk around on thin ice, being careful what they say and do. They often feel so responsible for us, so sympathetic with us, so afraid they will upset us even more.

Children should be encouraged to speak their truth and their thoughts and feelings, even when it’s hard for us to hear. If you can’t listen without judgment or criticism or getting upset, help them find another person—someone more detached and more objective—they can talk to.

Their whole world has been shattered. They wonder what will happen next. When they have open and honest communication with their parents—or at least with one understanding adult—they begin to feel a part of the solution instead of part of the blame.

How Are You Doing?

Before you go on to the next portion of the climb, ask yourself if you can agree with the following self-evaluation items:

- I’m beginning to recognize the masks I’ve been wearing.

- I’d like to be more open with the people I care about.

- I’m willing to face the fears behind my masks, even though it’s scary.

- I’ve risked sharing with a trusted friend a fear I’ve been hiding.

- I’ve asked a trusted friend for some honest feedback about myself.

- I’m beginning to understand the value of openness in relationships.

- Openness is becoming more natural for me.

- I can choose to wear an appropriate mask when it’s important.

- My masks don’t control me anymore.