2

England and Its Colonies

The great eastern Virginia Indian chief Powhatan (or Wahunsonacock) had a daughter named Pocahontas. She was probably about ten when the English colonists established Jamestown near her home. The girl came to Jamestown frequently, bringing gifts of food or notes from her father to the English leaders. Pocahontas would play with the English boys (few girls or women came to early Jamestown), teaching them to do cartwheels. She also became an intermediary between the Algonquian-speaking Powhatans and the English. In a time of surging tension, the English plotted to hold Chief Powhatan captive, but the Powhatans turned the tables and captured Virginia leader Captain John Smith instead. When Smith came before Powhatan, the chief ordered two large stones to be dragged before him, and Powhatan’s men grabbed Smith and forced his head onto the stones, “being ready with their clubs, to beate out his braines.”

Pocahontas suddenly intervened, cradling Smith’s head in her arms. She “hazarded the beating out of her owne braines to save mine,” Smith wrote gratefully. What Smith read as an act of romantic chivalry, however, was likely a preplanned ritual. Powhatan was signaling Smith’s adoption into the tribe as a lieutenant for the chief. This would have obligated Smith to serve and cooperate with Powhatan. Europeans, Indians, and Africans lived in a world full of misunderstandings. These unfamiliar cultures clashed with each seeking to tip the balance of power in their favor, even as they struggled to understand what the other side intended. This confusion and competing for power was a formula for escalating violence.

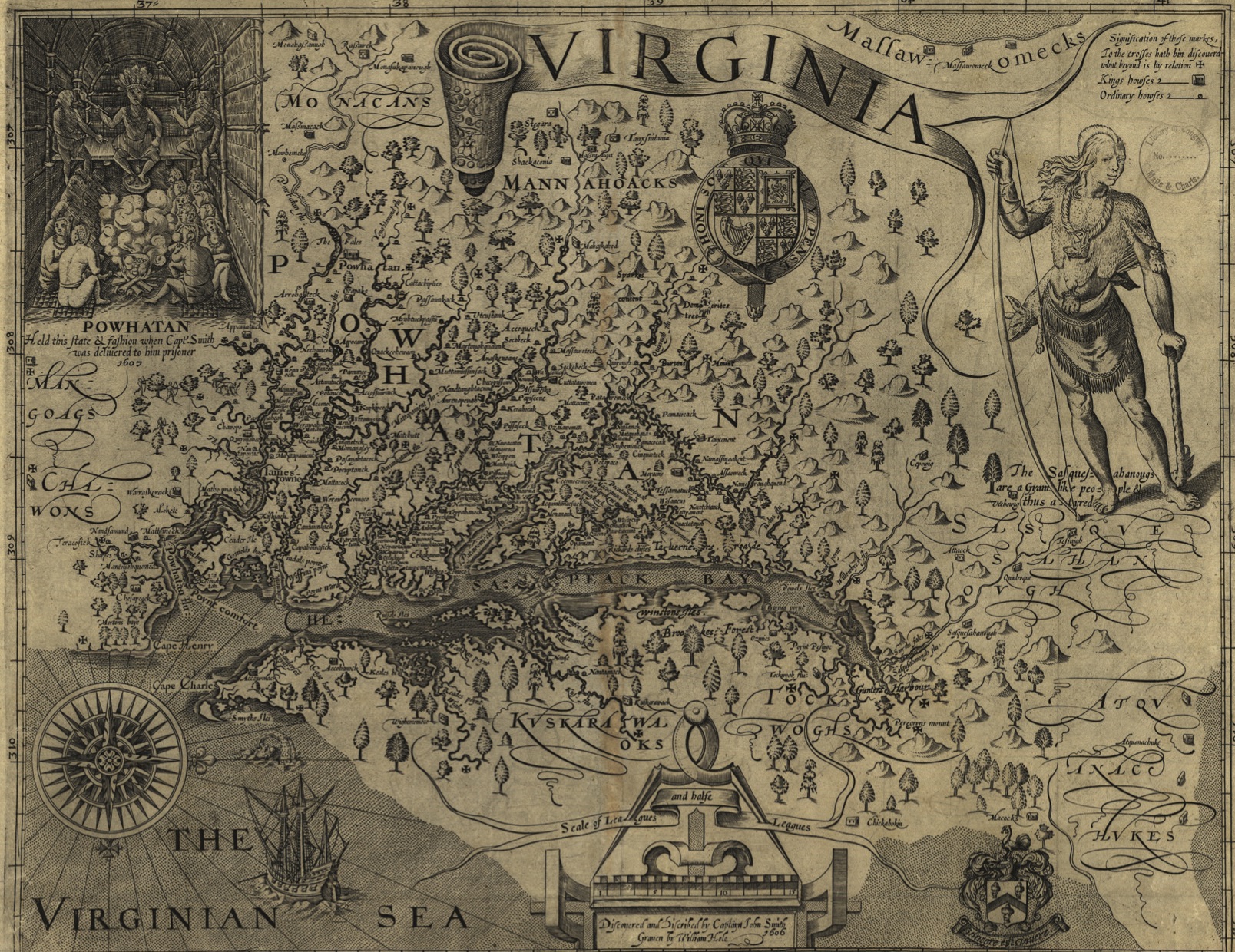

Virginia

When King James I succeeded Queen Elizabeth I in 1603, he focused England’s attention more closely on founding New World colonies. The English, like the French and Spanish, saw American colonies through the lens of mercantilist philosophy. Even if they did not always produce the gold and silver of which the earliest explorers dreamed, colonies could supply raw goods such as agricultural products, furs, or timber, and they could expand the available markets for English refined products. The colonies could also help the English address besetting social problems of homelessness, crime, and religious unrest by encouraging undesirable people to immigrate. Land was abundant and cheap in America, or it would be once the colonists had dealt with the indigenous people who currently lived there.

Following up on the disappointment of the Roanoke Colony in the 1580s, King James I in 1606 authorized the creation of the Virginia Company of London. This was an example of a new financial venture called a joint-stock company, which would solicit many investors in a common enterprise such as starting a colony. In 1607, 104 men and boys arrived in Virginia. They sailed up a river they named the James and built a settlement, called Jamestown, on the bank. The site made sense to the settlers since it was defensible from Spanish and Indian attacks. But it was surrounded by salty marshes, perfect breeding grounds for disease-carrying mosquitoes, thus ensuring horrifying early death rates at Jamestown and demonstrating that not only Native Americans suffered from disease and malnutrition in early America.

Between 14,000 and 20,000 Indians lived in eastern Virginia when the Jamestown settlers arrived. The Powhatan confederacy of tribes was one of the most powerful Indian groups along the whole Atlantic coast at the time. They demonstrated repeatedly that they were capable of countering and even defeating English power in Virginia. Before the colonists even entered the James River, they erected a cross on the shore of Chesapeake Bay to indicate their claim on the land. One of Jamestown’s leaders stated that the English planned to inform the Powhatans “of the true God, and of the way to their salvation, and finally teach them obedience to the King’s majesty.” But the English colonists, even those driven primarily by religious motives, tended to do less direct missionary work with Indians in America than did the Catholic Spanish or French colonists. The Jamestown colonists had ministers and a church but no missionaries per se.

It was clear from the beginning that the Jamestown colonists had gotten in over their heads. Expecting to find a virtual paradise in the New World, some imagined their stay in Virginia would be short and they could return to England as wealthy men. Thus, few of the early colonists envisioned that they would need to cultivate the land. Few knew the skills of farming, anyway. Early searching for precious metals and a river passage into the far west proved futile. Desperation set in within a year, and by the end of 1608, probably more than half of those who had come to Jamestown had already perished. Violence with Indians compounded the dire situation. The “Starving Time” in winter 1609–10 saw three-quarters of the remaining colonists die. In the bleak winter conditions, starvation led to horrors: people ate whatever moved, including snakes and rats. Rumors circulated that some Virginians resorted to cannibalism. Recent excavations of an early Jamestown trash pile found human remains scattered alongside the butchered bones of rats, dogs, and horses. The human bones had knife marks on them, which archaeologists think may confirm that cannibalism did occur.

Jamestown settlers scrambled to find more sustainable economic ventures than the elusive quest for gold. They experimented with mining iron and copper, harvesting timber, and making wine. But in the mid-1610s, they finally realized that the “stinking weed” the Spanish called tobacco would become their economic salvation. The Upper South and Chesapeake proved to have an ideal climate for growing tobacco, which had a ready market among Europe’s smokers. By 1617, an observer noted that the small colony’s “streets and all other spare places are planted with tobacco.” Growing prosperity meant that the colony needed more laborers. At first these workers came primarily from England as indentured servants. These impoverished laborers agreed to a term of indenture, usually four or seven years, in exchange for transport across the Atlantic. During their term of indenture, they would work at the command of their master.

The everyday life of indentured servants often looked like that of a slave, including the threats of being beaten or chained. The primary difference between servants and slaves, besides the length of service, was that English servants could file abuse claims in court. Such suits pepper the legal records of early America. One Maryland servant, Elizabeth Sprigs, wrote that she was sometimes “tied up and whipp’d to the degree that you’d not serve an animal,” and that sometimes the slaves were treated more humanely than servants. Once their term was up, assuming they survived, the indentured servants could gain their freedom. They could even dream of owning their own land, an aspiration that was impossible for the poor in England. The southern labor system took an important turn in 1619, however, with the arrival of “20 and odd Negroes” in Virginia. It is not clear whether these workers were considered slaves or indentured servants. It would take decades for Virginia’s tobacco planters to turn primarily toward African slaves as the basis of field work, but the wealthiest planters were doing so in the mid-seventeenth century.

The growth of the tobacco economy also meant that the English put growing pressure on local Indians to surrender their lands. Colonists vacillated between their stated goal, evangelizing Powhatans, and warring against them. A hopeful moment seemed to come when the English captured Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas and convinced her to accept Christianity. In 1614, she married the English settler John Rolfe in the Jamestown church, which was the first Protestant church building erected in America. (Archaeologists at Jamestown only rediscovered the foundations of that church in 2011.) In 1616, John Rolfe and Pocahontas, now known as “Lady Rebecca Rolfe,” went to England to stir interest in the work of the Virginia Company. But the twenty-year-old Pocahontas died before the couple could return to Virginia.

During the colony’s most desperate times, company executives ruled Jamestown under martial law. Some of its most severe threats of punishments were directed at blasphemers. For example, anyone who violated the third commandment by taking the Lord’s name in vain could have his or her tongue cut through with a knife. The colony introduced a system of representative government, however, in the late 1610s, with the creation of a general assembly. In 1619, the legislature began meeting in Jamestown’s church, which was affiliated with the Church of England. Among their first items of business were requiring church attendance on Sundays, encouraging further evangelization of the Powhatans, and regulating the colony’s crops, including tobacco.

The Powhatans’ conflict with Virginia had festered for fifteen years, and in 1622, they finally struck in a coordinated assault on nineteen of the colony’s settlements along the James River. Some 350 English colonists died, or about a third of Virginia’s white population. Angry survivors determined they should destroy the Indians “by all means possible,” as Captain John Smith put it. The era of Christian evangelization in Virginia largely came to a close because of the Powhatan uprising. But political changes came too. King James I realized that of the 14,000 people who had migrated to Virginia as of 1624, only about 1,100 survived and remained in the colony. The Virginia Company was bankrupt and floundering. So the king dissolved the company’s charter and took Virginia over as a royal colony. After 1624, the colony began to stabilize, powered by profits from the tobacco trade. The respective territories of the English and Indians were strictly demarcated. But as the English population grew, the Powhatans faced continuing pressure to move further into the interior.

Maryland

Although religion was pervasive at Jamestown, the colonists did not come primarily because of their faith. Religion was more central to the mission of Virginia’s neighbor to the north, the Maryland colony. England’s government had been aligned with Protestantism since the beginning of Elizabeth I’s reign. But King James I and his son, King Charles I (whose reign began in 1625), were more sympathetic to English Catholicism. Thus, Charles was willing to grant the Catholic proprietor Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore, land between the Potomac and Delaware rivers for a new colony in 1632. The name “Maryland” honored England’s last Catholic monarch.

The Calverts ruled and owned Maryland as hereditary proprietors. They aspired to make Maryland into a haven for English Catholics. The colony set the pace in honoring religious liberty when it adopted the 1649 Act Concerning Religion. No Christian would be persecuted for belonging to any particular denomination, the law said, nor would authorities deny them the “free exercise” of religion. Maryland’s assembly enjoined the colony’s residents to stop using religious epithets against one another, and they forbade anyone from using blasphemous speech. The Maryland proprietors took a lesson from the persecution of Catholics in England: if you did not appreciate being persecuted for your religious beliefs, then you should not persecute others for theirs. Political pressure and relatively small numbers of Catholics led to the end of the distinctly Catholic character of Maryland by the early 1700s, however.

The Maryland Assembly also passed a 1639 law stipulating that “all the inhabitants of this province being Christians (slaves excepted)” would have the same rights and liberties as “any natural born subject of England.” The Chesapeake colonies of Maryland and Virginia were both developing into tobacco-based economies that increasingly identified African slaves as a group set apart from the English. The early years of Chesapeake settlement saw greater dependence on indentured servants and sometimes on Native American slaves. Indentured servants were generally less expensive to acquire than African slaves. Given the high death rates for laborers, planters were hesitant to make substantial investments in individual workers. Perhaps as many as half of the indentured servants in the Chesapeake settlement in the 1600s died before their term of service ran out, often succumbing to diseases such as malaria. Native American slaves were in short supply, and enslaving native people who lived in relative proximity to the English tended to exacerbate the ever-present conflicts. Wealthy planters were the first to move toward buying African slaves. If the slaves survived, planters would own them and their labor, as well as their children, for life.

Many English planters treated indentured servants, Native American slaves, and African slaves in similar (and often brutal) ways, which suggests there was not a hard-and-fast racial division in the early Chesapeake labor regime. Black and white laborers often interacted and saw themselves as having much in common. In rare cases blacks who gained their freedom in the seventeenth century even went on to own slaves themselves. Whites’ rigid association of “black” with “slave” had not yet arrived. Still, Maryland’s “slaves excepted” note suggests that even in the early 1600s, ideas were emerging about the natural link between slavery and Africans, who were presumed to be non-Christians. (The fact that many African slaves had some background in Catholicism did not register with most English colonial lawmakers.)

Early Virginia was dominated by male settlers, including both planters and servants. Maryland’s proprietors tried to encourage more whole families to settle there. Virginia also took occasional measures to try to address the gender imbalance and dearth of marriageable women. In 1621, fifty-seven women and girls came from England and were effectively sold off to planters as wives in exchange for payment of the cost of the woman’s Atlantic voyage. Small numbers of female indentured servants also came to the Chesapeake. They found themselves especially vulnerable to abuse: one Virginia female indentured servant reportedly received an astounding 500 lashes as a punishment in 1624. In Maryland and Virginia, servant women frequently appeared in court to answer the charge of having given birth to children as unmarried mothers. Often their master, or a fellow servant, was the father, but such women could suffer fines or whippings for bastardy. If they lived out the term of their indenture, however, servant women occasionally found more opportunity for upward social mobility, usually through marrying a landowner, than they would have had in England.

New England

Religion undoubtedly motivated the little band of 102 colonists who founded Plymouth Colony in 1620. They represented the first wave of European settlers in New England, or the colonies to the east of New York. People often call the Plymouth settlers “Puritans” or “Pilgrims.” But the best name for them was “Separatists,” radical Protestants who had become convinced that the Church of England was so spiritually adrift that they could no longer attend its services. Many Separatists fell under severe persecution in England when they set up independent churches. Some Separatists left for the freer climes of the Netherlands. But even there, many of the Separatists feared that their children would fall into the temptations of Dutch culture. So a group of them left the Netherlands to travel to America, planning to go to Virginia, where the colony would afford them land. But the colonists ended up much farther north than they expected, at Plymouth, in what would become Massachusetts. There the adult men signed the Mayflower Compact, agreeing that the colony’s chief goals were “the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honor of our king and country.” The “people” compacting together to create a government was a key precedent for the US Constitution. But that note about devotion to King James I, and to England, reminds us that this was not a modern democratic venture.

“Puritans” and “Separatists” peopled early New England. Of course, Native Americans lived there already, and some of them had already suffered the dreadful effects of the new diseases. A Patuxet Indian village had once stood where the Separatists built Plymouth, but all that remained of the earlier native settlement were bones and derelict lodges. The Algonquian-speaking tribes of southern New England, from the Mohegans of Connecticut to the Nipmucks of Massachusetts, were more subdivided and locally organized than the Powhatans’ confederacy in Virginia. This made collaboration against the English more difficult. Like Indians farther south and west, the New England Indians had long since come to depend on corn, beans, and squash, but their proximity to the coast supplemented their diet with abundant fish and shellfish. The New England Indians’ interactions with European newcomers continued to have a distinctly maritime cast into the late colonial era. New England colonists looked to Native Americans as guides, couriers, and suppliers of food.

Among the most famous early interactions with Indians took place between the Plymouth colonists and the Patuxet Indian named Squanto (or Tisquantum), who greeted the colonists in surprisingly fluent English. By the time he met Plymouth’s pilgrims, Squanto had already ventured involuntarily through much of the European American world of the colonial powers. In 1614, English buccaneers had captured Squanto and taken him to Spain, where they attempted to sell him into slavery. Somehow Squanto ran away to London, where he learned to speak English, before making his way back to New England. When he returned to the Patuxet town, he found it deserted, with unburied skeletons lying about. An epidemic had wiped the settlement out while he was gone. When the Plymouth colonists arrived, Squanto took up with them as their interpreter, arranged a trading relationship for them with Indian fur trappers, and gave them advice about the best planting practices, including using fish for fertilizer. In 1622, Squanto died while traveling with Plymouth settlers on a trade mission. Like the French Canadian colonies, the trade in beaver and otter furs sustained Plymouth in its early decades. Squanto and many other Indian figures operated as intermediaries in trade systems that connected Native Americans to the European market for animal pelts and other commodities.

Both the Plymouth Separatists and the much larger contingent of Puritans who would found the Massachusetts Bay Colony were products of the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation had engulfed England in controversy starting in the mid-1500s. King Henry VIII led England’s formal break from the Roman Catholic Church in 1533, when the pope would not grant him an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, with whom he had failed to father a male heir. The English Reformation, then, had gotten off to a rather worldly start. Many English Protestants, for a century and more after the 1530s, believed the Reformation needed to go further in England. The Church of England, with its elaborate rituals and hierarchy of bishops and archbishops, retained too much of the trappings of Roman Catholicism and needed more purifying in accordance with the Bible. The term “Puritan” was a mocking name that opponents gave these advocates of biblical reform in the church. But for our purposes, the name is handy: the Puritans wanted to purify the Church of England, while the Separatists believed true Christians should separate from it.

In American popular culture, critics have often stigmatized the Puritans as killjoys and witch-hunters, basing their impressions on literary sources such as Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850) and Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible (1953), both of which cast the Puritans in a decidedly negative light. Whether we ultimately agree with the Puritans’ interpretation of Christianity, we must understand that they were trying to bring the whole Bible to bear on their families, churches, and societies. When they got the opportunity to establish a new society in Massachusetts, the Puritans believed they were obligated to make the Bible the rule of the entire colony. Like all Protestants, they emphasized access to the Bible for all people in their vernacular languages. Literacy rates for women and men were unusually high in colonial New England because of the priority given to Bible reading.

The sovereign power of God was the key doctrine of Puritan theology. As devotees of Calvinist theology (derived from the French reformer John Calvin), they believed God ruled over all things in the universe. Nothing was out of God’s control, not even the eternal fate of human beings. Like most Protestants, the Puritans believed in the principle of salvation by grace alone. But they had a particular idea of how God’s grace worked. The Puritans (and many Calvinists) taught the doctrine of predestination. God had “elected” a certain segment of humanity for salvation and left all other people to their own desires. But people are so corrupt that no one would choose God on their own. The non-elect always preferred separation from God and condemnation in hell. If God had not predestined the elect to salvation and graciously regenerated their hearts, they would never have accepted God’s forgiveness through Christ. Over the course of the eighteenth century, increasing numbers of anti-Calvinist critics said the concept of predestination was unfair: if everyone was sinful, why would God only predestine some and not others to salvation? Some people in Calvinist churches found predestination a source of anxiety, wondering if they could ever be saved. But many more have found it a comforting doctrine, knowing that God was absolutely in control of their salvation.

The Puritans believed Christian governments were obligated to enforce social morality. This is hardly unusual: all societies with legal codes designate certain behaviors such as murder and stealing as criminal and beyond the pale. But the Puritans embraced a more comprehensive view of morality. People who took advantage of the poor, showed contempt for authority, or engaged in behavior that might offend God could face penalties in seventeenth-century Massachusetts. As best they could, the Puritans sought to have the Ten Commandments and other biblical precepts reflected in their laws. Thus, Puritan officials would prosecute people for offenses such as Sabbath breaking. They believed leaving such sins unpunished would invite God’s judgment on their land. Private immorality was a public matter to the Puritans.

Because of their respect for biblical morality, one could easily get the impression that the Puritans were killjoys. (The early twentieth-century writer H. L. Mencken once defined Puritanism as the “haunting fear that somewhere, someone may be happy.”) Whether we would ultimately want to live among them, the Puritans did engage in some stereotype-busting behavior. One was that they drank alcohol, as did virtually all English people of the time. Of course, they were mindful of the Bible’s prohibitions against drunkenness, but they saw no problem with daily consumption of beer or hard cider. In an age of often-contaminated water supplies, alcoholic beverages were typically among the safest and most nutritious options for the colonists. Moreover, unlike their dour clothes in today’s movies, many Puritans wore brightly colored clothing, including satins and silks. And while the Puritans were against sex outside of marriage, they highly valued marital intimacy and romantic love between husbands and wives. The great Puritan poet Anne Bradstreet spoke of her love for her husband as one “that rivers cannot quench.”

As biblical “primitivists,” the Puritans wanted to implement what the Bible said to do and to lay all other traditions aside. Like many Christians through time, they believed the best model for Christian practice was the early, or “primitive” church. To them the early church appeared to be much simpler than the Roman Catholic or Anglican hierarchies of church officials. The church in the book of Acts had no sources of wealth or political might. Thus, Puritans believed the church needed to get back to a congregational form of church government. Church members, led by pastors and elders, would govern themselves instead of submitting to bishops and archbishops. Church membership was hardly automatic to the Puritans, unlike in the Church of England’s parish model. In the parish model, if you were born into an Anglican parish and received baptism there (as an infant), you were considered part of the church. The Puritans only admitted those to church membership who had hopeful signs that they had experienced conversion, or a transforming work of God’s grace. (This high standard explains why church membership in early New England remained fairly low, even though church attendance was legally required.) The Puritans of New England did not endorse separatism and did not formally repudiate the Church of England. Their journey across the Atlantic functioned as a declaration of their independence from the power of England’s church rulers, however.

The Puritans needed that functional independence because in the 1620s England’s political and churchly authorities had become increasingly antagonistic toward them. King Charles I named the anti-Puritan minister William Laud the archbishop of Canterbury (the top leader in the Anglican Church). Laud’s goals were, in many cases, the exact opposite of the Puritans’. He wished to bolster the power of the church hierarchy and to make ministers closely observe the traditional Anglican rituals of the Book of Common Prayer. Ministers who would not comply faced expulsion from their pulpits, and some Puritans began to wonder if England was preparing to go back to Roman Catholicism, which they associated with the spirit of “Antichrist.”

The Puritan Migration

The majority of Puritans never did leave England. Some left for New England, or the Caribbean, and then returned to England several years later. But in 1629, an influential group of Puritans decided to form a colony in the New World where they could practice their faith in peace. Massachusetts governor John Winthrop, a lawyer, told his wife that he believed God was creating an American “shelter and hiding place for us.” Winthrop helped create the Massachusetts Bay Company, and in 1630, he and 700 other Puritan sympathizers sailed for New England. At some point, on the eve of the voyage or during the journey itself, Winthrop delivered his celebrated address “A Model of Christian Charity.” In it he charged the Puritan migrants that they must “follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God.” God and the people of England were watching. Citing Matthew 5:14, Winthrop said, “We shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God . . . we shall shame the faces of many of God’s worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are a going.” This was a sacred mission with dire consequences if they did not remain faithful to their calling.

New England was not the only possible destination for Puritans. Some Puritans appeared in places such as Virginia and Bermuda. Others founded a distinctive but short-lived colony at Providence Island, off the coast of Nicaragua. Massachusetts and Providence Island were founded the same year, in 1630. But while Massachusetts took on the character of a refuge, Providence Island was more oriented toward confrontation with Spanish colonial power. Proprietors said that Providence was ideally located for Protestant forays against the Spanish “man of sin,” referring to 2 Thessalonians 2:3. But the governors and pastors of Providence could never agree whether power, moneymaking, or piety was the main purpose of the colony. Conflict with the Spanish marked the whole history of the colony, culminating in Spain’s conquest of Providence Island in 1641. Unlike the New England colonies, Providence Island became deeply dependent on slave labor by the mid-1630s. The New England Puritans had slaves, too, but in small numbers. The climate and soils of New England did not lend themselves to large plantations and cash crops. If they had, the future course of American history could have been different with regard to regional cultures of slavery. As it was, New England’s farmers tended to grow food for their families and local markets. The key New England exports were furs and timber for shipbuilding.

Although most New Englanders would never achieve the kind of wealth southern planters did, the early history of New England was more stable than that of Virginia or the Caribbean colonies. Entire families generally came to New England, rather than single men. Puritan men were often middle-class professionals, including lawyers such as Winthrop, or the learned clergymen who presided over the churches of each New England town. The chilly climate also meant disease-bearing mosquitoes were less of a problem than in the southern colonies. Fewer people migrated to the New England colonies in the first half of the seventeenth century than to Maryland and Virginia, but by 1660, New England and the Chesapeake had roughly similar populations of about 35,000 English colonists.

Early New England was no tranquil paradise, though. Almost immediately, Massachusetts faced conflict with Native Americans and internal disagreements over theology. The seal of the Massachusetts Bay Company had featured a Native American saying, “Come over and help us,” a reference to a vision the apostle Paul had in Acts 16:9. But New Englanders did comparatively little to evangelize Native Americans. Little time passed between the founding of the colonies and the outbreak of war with the region’s Indians. In the mid-1630s, English colonists allied with Mohegan and Narragansett Indians and sought to destroy the Pequots of Connecticut. (Connecticut was founded as a Puritan colony in 1636.) The war was gruesome. Its most horrific episode came in 1637 with the English attack on a Pequot settlement at Mystic River in Connecticut. Most of the fighting-age men were absent from the Mystic village, leaving hundreds of elderly, women, and children behind. Nevertheless, the English set fire to the Pequot dwellings, burning most of the villagers there to death. They finished off the rest with their swords. Most of the Pequot tribe was exterminated in the war, but some of those who remained alive were sent to work as slaves on Providence Island.

Theological Division in New England

Massachusetts also endured great public controversies over theology and Christian practice. The Puritans had come to America for the freedom to practice biblical religion themselves. But they did not believe in extending religious liberty to dissenters. No one had the right to openly disregard the principles of God’s Word, they thought. If anyone disagreed with the Puritans’ interpretation of Scripture, they had full freedom to leave the colony. If they would not leave, the Puritans would banish them. This was the fate of dissenters including Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson.

Both Williams and Hutchinson had come to Massachusetts as Puritans. The First Congregationalist Church of Boston even offered Williams their pastorate. But Williams was already developing Separatist convictions about the need to explicitly denounce the Church of England, so he spent a good deal of time among the Separatists at Plymouth (which remained distinct from Massachusetts until 1691). Although Massachusetts did observe some forms of church-state separation—ministers could not serve in political office, for example—Williams still felt that the entangling alliance between the Massachusetts government and its churches would inevitably corrupt the churches. The government should enforce laws about the way people interacted with one another, but no government should coerce anyone to worship God in a certain way. Williams also spoke out against Massachusetts’ abusive treatment of Native Americans. In the mid-1630s, Massachusetts officials banished him, so Williams founded the Rhode Island colony, south of Massachusetts. For a time Williams identified with the emerging English Baptist movement, so he founded America’s first Baptist congregation in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1638. (Baptists, banned from entering Massachusetts in 1644, were distinctive in their refusal to baptize infants, the standard practice of most other Christian groups at the time.) Rhode Island granted liberty of conscience to many different religious groups and refused to “establish,” or give legal advantages to, any one denomination.

Anne Hutchinson and her family had followed the popular Puritan minister John Cotton to Massachusetts. The dynamic Hutchinson soon began hosting home-based meetings in Boston to discuss Cotton’s sermons. Such women’s meetings were not unusual, but men also attended her informal teaching sessions. Hutchinson raised the ire of Puritan authorities when she began to suggest that only a couple of the town’s ministers, including Cotton, accurately taught salvation by grace alone, the distinctive doctrine of the Protestant movement. The Puritan pastors focused so much on morality, she said, that people got the impression that by being good, they assisted in their own salvation. This was bad theology, she insisted. People could do absolutely nothing to earn God’s grace. It was all up to God.

Puritan leaders, including Governor John Winthrop, thought Hutchinson’s teaching was subversive. They said it smacked of “antinomianism,” or the belief that Christians were not obliged to obey God’s moral laws. The two sides were not really that far apart: this was just the latest flare-up in a long-running debate among Protestants over the role of good works in the Christian life. Historians have long debated how much of the authorities’ rage against Hutchinson had to do with her being a woman. Women were taken seriously, comparatively, in Puritan spirituality. They were believed to have a direct relationship with God and could read and understand the Scriptures themselves. On the other hand, the Puritans (like most Christian groups) did not give women access to pastoral roles. Hutchinson had adopted a de facto ministerial position for her followers. Winthrop told Hutchinson that the meetings she hosted were not “fitting for your sex.”

The charges against Hutchinson ran along two tracks. One was her theology; the other was her public role as a female teacher. At her 1637 trial, the judges demanded to know where Hutchinson got her antinomian-sounding ideas. She replied that God had given her a prophetic gifting and that the Holy Spirit revealed spiritual truths directly to her. Again, most Christians would have agreed that the Holy Spirit lived inside true Christians, but the judges could not tolerate a woman claiming that the Spirit revealed special truths to her that contradicted the teachings of the official ministers. This was asking for chaos. Massachusetts banished Hutchinson and her family from the colony.

Dissent was difficult to suppress entirely in New England, but the Puritan colonies showed a great deal of religious unity in the early decades of settlement. Early New England was far more churched than was the colonial South, which had a reputation for godlessness. Still, almost from the outset, some Puritan ministers worried that Massachusetts and Connecticut were not living up to their calling as a “city on a hill.” Church membership remained low. Those who experienced conversion and joined the church as full members could participate in the Lord’s Supper and could have their children baptized. But as New England became filled with more church-attending nonmembers, it raised the question of what to do with their children. What would the churches do with legions of unbaptized children whose parents wished to raise them as Christians? Thus, in 1662, the Puritan ministers devised a plan called the Halfway Covenant, which permitted churchgoing nonmembers to have their infants baptized. Although the Puritans had insisted that they would correct the corruptions of the Church of England, some critics regarded the Halfway Covenant as a step back toward the parish model in England. In that model, people considered themselves part of a church—or even as heaven-bound Christians—simply because they lived within the parish boundaries of a church and were baptized there.

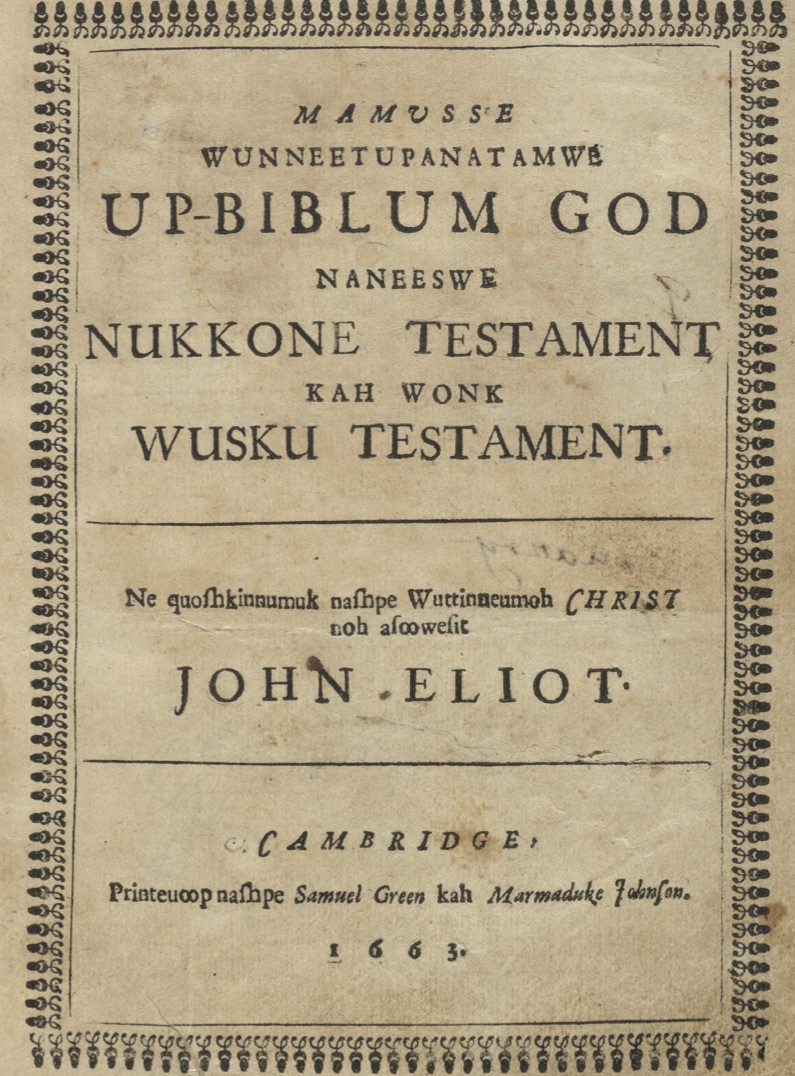

The mid-1600s also saw modest Puritan efforts at evangelizing the Indians who had survived the first waves of disease and the wars with the English. The key English figure in this evangelistic effort was the minister John Eliot. Eliot started to learn the language of the Massachusett Indians in the 1640s and planted fourteen “praying towns” for Christian Indians before the outbreak of King Philip’s War in the 1670s. Eliot, along with a Montaukett servant named Cockenoe and a Narragansett named Job Nesutan, produced the Massachusett-language Bible, called the “Eliot Bible.” This translation of the Geneva Bible was the first edition of the Scriptures published in English America. Historians are divided about how deeply Native Americans embraced the Christian message of Eliot and other missionaries. The Puritans were cautious about accepting native churchgoers as converted believers, partly because such a premium was put on a convert’s being able to articulate his or her conversion experience in theologically precise language. Nevertheless, the Puritans permitted the founding of native churches in Natick, Massachusetts, which was Eliot’s most prominent praying town, and on Martha’s Vineyard. In 1670, a Wampanoag convert named Hiacoomes became the first ordained Indian minister in the English colonies.

Figure 2.2. Title page from Mamusse wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God naneeswe Nukkone Testament kah wonk Wusku Testament, translated into the Massachusett language by John Eliot. Cambridge, MA: 1663. The Eliot Indian Bible was the first Bible printed in America.

The Middle Colonies

The English colonies between Maryland and New England, including New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, are typically called the “Middle Colonies.” As this generic name implies, there never has been as cohesive a story to tell about the Middle Colonies as the South’s plantations and New England’s religion. The Middle Colonies were ethnically and religiously diverse in ways New England and the southern colonies were not. Even among the region’s European-born settlers, no one group dominated.

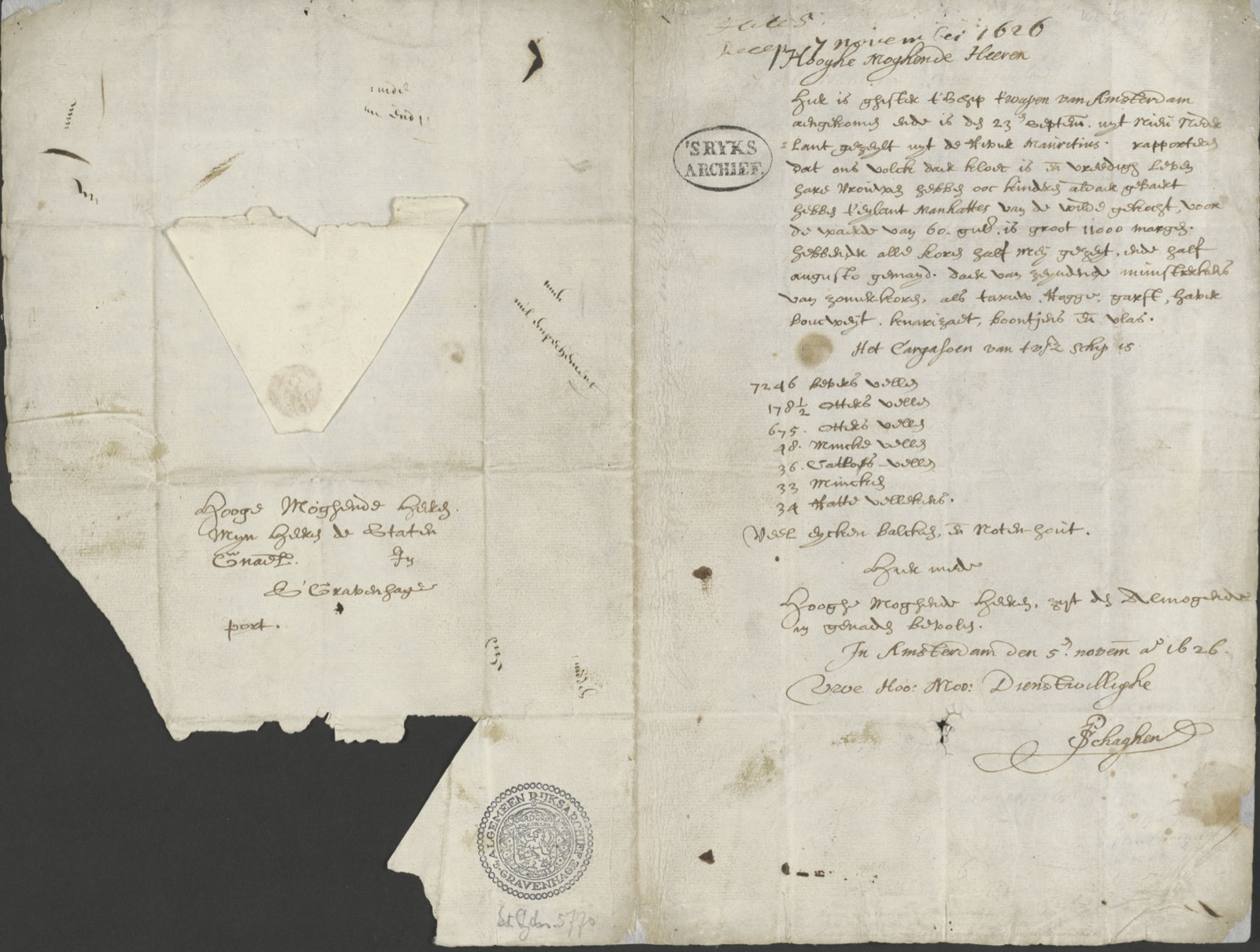

Among the Europeans the Dutch made the first permanent mark on the Middle Colonies with the founding of New Netherland (later New York) in 1624. English explorer Henry Hudson, working on behalf of the Dutch, had reconnoitered New York Harbor and the river that would soon bear his name in the early 1600s, hoping to find the ever-elusive water passage to Asia. He took the Hudson River as far north as the future site of Albany, where he realized the route was unlikely to get him to Asia. Still, the Dutch established a tiny trading post there called Fort Nassau in 1614 and began trading with the Iroquois Indians, especially Mohawks, for furs. This first Dutch settlement in America came chronologically between the English foundings of Jamestown and Plymouth.

The Dutch created the Dutch West India Company in 1621, charging its officers with establishing a Dutch commercial presence in the Western Hemisphere. They also wanted to challenge the colonial power of the hated Spanish, with whom the Dutch were engaged in decades of struggle for control of the Netherlands itself. In the early years of Dutch colonization, their major overseas project was in Brazil. But they also created a small settlement at New Amsterdam on Manhattan Island, which the Dutch “purchased” from local Lenni Lenape Indians for goods in the “value of 60 guilders.” Europeans and Indians had different ideas about what it meant to “buy” land. The Lenni Lenapes likely understood the presents as tribute, for which they would allow the Dutch to erect a settlement on the southern shore of the island. Most natives did not initially share the European concept of a person or people owning exclusive right to use a piece of property.

In spite of its small size (about 270 people in 1628), New Amsterdam quickly became the most diverse place in early America. In addition to the Dutch, there were Finnish, German, and Swedish residents as well as English migrants from New England and from England itself. The colony also absorbed the tiny settlement of New Sweden, Sweden’s lone American mainland colony, in 1655. Communities of free Africans as well as slaves appeared in New Amsterdam by the mid-1600s. The diversity fed instability in New Amsterdam, which endured rampant crime and conflict. At one point around mid-century, the town had about 200 houses, 1,000 residents, and a remarkable thirty-five taverns to feed residents’ taste for alcohol. The streets were filled with trash, dead animals, and human excrement.

Although New Amsterdam never seized on plantation agriculture, slavery became central to its economy. Many slaves lived in or passed through the city, and the colony of New Netherland became focused on supplying food for plantation colonies in the Caribbean and Brazil. New Netherland saw typical patterns of early violence against local Native Americans. Grotesque scenes replicated those of the Pequot War and the assault on the Mystic River village in the 1630s. The Dutch offered bounties for any decapitated heads of Raritan Indians that European fighters brought back to New Amsterdam. Dutch involvement in the fur trades destabilized the relations between the French, the tribes of the Iroquois League, and other Indian groups such as the Hurons. The resulting economic turmoil triggered the “Beaver Wars” of the mid-1600s, in which the Iroquois engaged in brutal conflicts against many of their Native American neighbors. This was the context for the Iroquois destruction of the French Jesuit mission at Sainte-Marie in the late 1640s, which we noted in chapter 1.

Figure 2.3. Island Manhattes document used as a deed for Manhattan Island, written by Pieter Schaghen, 1626.

Pieter Stuyvesant became colony director of New Netherland in 1647 and brought a measure of order to the unruly Manhattan settlement. He tried to regulate prices for foodstuffs, including beer and bread, and mandated that land purchases from Indians be subject to government approval. New Netherland’s diversity extended to its religious environment. The Dutch Reformed Church enjoyed official status in the colony, but officials permitted a wide range of religious groups to operate quietly and in private. Stuyvesant insisted that none of these groups—Lutherans, Catholics, or Puritans—should be allowed to meet openly or try to evangelize the Dutch Reformed. New Netherland even saw the arrival of small numbers of Jews in the 1650s, some of whom came as refugees after the Portuguese took over the Dutch colony in Brazil. Dutch authorities had the most difficulty with the Quakers, a radical Protestant group that flourished during the English Civil War of the 1640s and ’50s. The Quakers were notorious for refusing to obey orders to remain publicly silent about their faith. The colony warned residents to report the activities of any Quaker missionaries and to give them no shelter. This dictate resulted in the celebrated Flushing Remonstrance of 1657, in which the people of Flushing, New Netherland, protested the colony’s order, saying they would treat the Quakers “as God shall persuade our consciences.” The Flushing Remonstrance was an important early statement of the rights of religious conscience in American law.

The Dutch kept control of New Netherland for only forty years. In 1664, the English sent warships to conquer the small village on Manhattan Island. Pieter Stuyvesant called on the people of New Amsterdam to resist, but they refused. The transition to English rule went fairly smoothly, and the English allowed Dutch residents to maintain their property in “New York,” named for James, the Duke of York and brother of Charles II. Evidence of long-standing Dutch influence remained in English New York, in place names such as Brooklyn (originally “Breuckelen”), for example, and the road and neighborhood called the Bowery (“Bouwerij”), both of which dated to the seventeenth century.

The Quakers

The Quakers first made their presence known—often via boisterous preaching—across America in the 1650s. They appeared from the New England colonies to the Caribbean island of Barbados. Like “Puritan,” the name “Quaker” was a term of insult. It referred to the way the Quakers, who called themselves the “Friends of Truth” or “Society of Friends,” supposedly shook as they worshipped or preached. Most traditional Christians held that the Holy Spirit of God dwelled within Christian believers, but Friends contended that the “Inward Light” of Christ dwelled in every person, regardless of religion, gender, race, or social status. The doctrine of the “Inward Light” made the Quakers unusually egalitarian, or focused on the equality of all people. They accepted women as itinerant evangelists and were among the earliest Anglo-American critics of the transatlantic slave trade.

Massachusetts authorities despised Quaker agitation even more than New Yorkers did. During the period 1659–1661, Massachusetts executed several Quaker missionaries. These missionaries had provocatively returned to Massachusetts after receiving a sentence of banishment. Quakers played a major role in the early settlement of West Jersey (East and West Jersey were combined into a single royal colony, New Jersey, in 1702). But the primary Quaker venture in the New World was in Pennsylvania, founded by the Quaker William Penn in 1682. Penn, who converted to Quakerism in the 1660s, came from an aristocratic English family to which the English government owed money. King Charles II granted Penn a charter for the new colony as a means to pay off that debt. He also hoped to get some of the troublesome Quakers to leave the British Isles. In its original laws Penn’s colony guaranteed religious liberty to its residents. Pennsylvania promised that no one would be “prejudiced for their religious persuasion or practice, in matters of faith or worship, nor shall they be compelled, at any time, to frequent or maintain any religious worship, place, or ministry whatever.” Though Quakers would exercise great political influence in the colony, they did not make themselves into an established church. The colony’s religious freedom did have limits, however. Pennsylvania’s proprietors would not tolerate atheists, and they enjoined people to observe the Sabbath.

Thousands of Quakers and other religious asylum seekers poured into early Pennsylvania, helping the colony grow quickly. As in New England, the Pennsylvania Quakers tended to arrive as whole families. Soil and climate made Pennsylvania ideal for growing wheat, rather than the labor-intensive tobacco or sugar of the colonies farther south. Quaker qualms about slavery, and the cultivation of wheat, meant that Pennsylvania did not become dependent on slave labor. Pennsylvania also had a relatively peaceful relationship with local Native Americans for its first half century. William Penn wished for the colony to present a model Christian society to the Indians, one not marked by the violence of the Spanish colonies or the other English settlements. Surprisingly, the Quakers did not do much to evangelize the Indians. They did more to proselytize African slaves on Barbados, by comparison. The modest inroads the Quakers made among Africans in the Caribbean precipitated a backlash among some leading planters, who feared that Quaker Christianity would make the slaves rebellious.

The Colonial South and the Caribbean

We often neglect the English Caribbean colonies in the story of early American history because they did not join the thirteen mainland colonies in the American Revolution. But in the colonial era, most people in England would have agreed that the Caribbean colonies were the most important in the Americas. They made England the most money, and they directly challenged Spanish power in the Western Hemisphere. Among the early English Caribbean colonies, Barbados was the most significant. Founded in 1627, Barbados modeled a slave-dependent economy devoted to growing sugarcane. Barbados and the other Caribbean colonies helped feed Europe’s voracious appetite for sugar. By the late seventeenth century, the small island had a majority population of African slaves. The Puritan colony at Providence Island might have followed a similar path, had the Spanish not conquered it.

Spanish-English conflict in the Caribbean generated a number of such conquests in the 1600s. The English took Jamaica from Spain in 1655, and it would become another key sugar island as well as a haven for privateers and other pirates. The famous English pirate Henry Morgan, operating out of Jamaica’s Port Royal, marauded Spanish settlements and ships from Cuba to the northern coast of South America. But sugar was the main business of those who lived on the island, and by the 1680s, Africans outnumbered whites in Jamaica three to one. A hundred years later, 90 percent of Jamaicans were enslaved. The island and its brutal sugar regime could barely support any native-born population, since so many slaves died from the extreme conditions in the fields and from diseases such as smallpox.

The sugar islands quickly ran out of farmable land. The younger sons of planter families in Barbados often looked for opportunities elsewhere. One of their most common destinations was the new colony of Carolina, founded in 1670. (North Carolina would become a separate colony in 1712.) The lead founder of Carolina was Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper. Cooper worked with his secretary, John Locke, to develop the colony’s Fundamental Constitutions. Locke would go on to become the most significant Enlightenment philosopher in England. Locke and Cooper’s frame of government provided for religious toleration, reflecting a major priority in Locke’s later writings such as his 1689 Letter Concerning Toleration. Given its southern location and Caribbean origins, there was no doubt that Carolina would depend on slavery, so the law gave each planter “absolute power and authority over his negro slaves.” In 1680, the colony’s capital was settled at Charles Town (later Charleston), at the confluence of rivers that the English named the Ashley and the Cooper. Charleston Harbor would be the stage for the beginning of the American Civil War 181 years later.

The English in Carolina, like those in Barbados, Jamaica, and Virginia, were motivated more by commercial concerns than by religion. Although some Anglican missionaries worked among Native Americans and Africans, the enslavement of both people groups chiefly marked their relationships with the English in Carolina. The English bartered with southern Native Americans for deerskins and Indian slaves and provided the Indians guns and other manufactured products. As in New France, the English trade in animal pelts transformed the American interior and the Native Americans’ hunting patterns. While they had previously hunted deer for subsistence clothing and food, now Indians hunted more exclusively to get deerskins for export. Often they had no use for the surplus meat and bones, leaving stripped deer carcasses to rot in the woods. Farmers found that the Carolina low country around Charles Town was not ideal for growing either sugar or tobacco. Eventually they seized upon rice as the key crop for the colony. Cotton played only a minor role in the South Carolina economy until after the American Revolution, when the South became the “cotton kingdom.”

Death, enslavement, and economic disruption among southern Native Americans led to outbreaks of war between some tribes and the English. Starting in 1711, the Tuscaroras of North Carolina tried to push back English settlement there. North Carolina had virtually no defensive forces, so South Carolinians came to their aid, raising a militia composed mostly of Indian allies, including Cherokees, Creeks, and Yamasees. They destroyed the Tuscaroras’ most important town in 1713, putting to death more than 150 Tuscarora warriors and taking several hundred children and women back to South Carolina as slaves. (Tuscarora refugees soon made an alliance with the Iroquois League, becoming its sixth affiliated tribe.)

The English also turned against their Yamasee allies, precipitating the devastating Yamasee War of 1715. The Yamasees rebelled against the English, who held massive Yamasee debts and who were taking Yamasee slaves as payments. The Yamasees killed hundreds of frontier traders and settlers in Carolina. Embittered Tuscaroras helped the English and other Indian allies in the campaign to rout the Yamasees. But the Yamasees discovered that they had become fatally dependent on English guns. When the English cut off their firearms supply, the Yamasees were unable to fight. Yamasee survivors sought refuge with the Spanish in Florida, who were always eager to recruit new Indian allies against the English.

Georgia

Tension between the southern English colonies and Florida explains the founding of Georgia, the last of the mainland English colonies in America. Georgia’s founder, James Oglethorpe, believed Georgia could serve as a buffer against Spanish expansion and also provide a haven for Protestant refugees from the continent of Europe. In 1732, King George II gave Oglethorpe a charter for the new colony, which the Georgia trustees named for the king. The founders envisioned Georgia as a different kind of southern colony, so they originally banned both slavery and rum. Although the colony clearly had imperial and commercial purposes, Oglethorpe also wanted Georgia to become a model Christian community. Almost immediately the vision of the Georgia founder clashed with reality. Settlers clamored for slaves, seeking to enjoy the same profits as their South Carolina neighbors. Few of the early colonists in Georgia were of English background: many came from Scotland or Germany. They resented the way Oglethorpe and the colony’s trustees ruled from England by fiat. The colonists took to calling Oglethorpe the “perpetual dictator.” By the early 1750s, Georgia became a royal colony, and the ban on slaves was dropped. In the next couple of decades, Georgia’s economy and labor system started to look more like a typical southern colony.

The arrival of the English and other Europeans in eastern North America and the Caribbean unleashed massive transformations for Native Americans such as Pocahontas and her father, the chief Powhatan of eastern Virginia. The changes often began with epidemic diseases, but soon most eastern Indians faced pressure to give up land. The English economy also drew Native Americans into unfamiliar patterns of hunting animals for export and introduced them to new technologies, such as guns, that would add to the violence of the first century of English colonization. The English planters also demanded African and some Indian slaves to help grow tobacco, rice, and sugar. Thus, the European colonization of the Americas was a fully Atlantic event, bringing massive changes to Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

Although religious beliefs were pervasive, the English colonies were divided about their original purposes. The New England colonies and Pennsylvania, for instance, began with a clear religious mission. Others, such as Virginia, New York, and Carolina, had a commercial bent, even if colonial leaders were aware of their Christian obligation to evangelize Native Americans. Too often, wars between the English settlers dashed whatever hopes the white colonists might have had of bringing substantial numbers of Indians into the Christian fold. Europe’s imperial powers increasingly focused on a contest for control of North America. That contest would produce the Seven Years’ War.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bremer, Francis J. The Puritan Experiment: New England Society from Bradford to Edwards. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1995.

Carr, Lois Green, and Lorena S. Walsh. “The Planter’s Wife: The Experience of White Women in Seventeenth-Century Maryland.” William and Mary Quarterly 34, no. 4 (October 1977): 542–71.

Demos, John. A Little Commonwealth: Family Life in Plymouth Colony. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Dunn, Richard S. Sugar and Slaves: The Rise of the Planter Class in the English West Indies, 1624–1713. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972.

Horn, James. A Land as God Made It: Jamestown and the Birth of America. New York: Basic Books, 2005.

Jacobs, Jaap. The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009.

McIlvenna, Noeleen. The Short Life of Free Georgia: Class and Slavery in the Colonial South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Morgan, Edmund. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W. W. Norton, 1975.

Townsend, Camilla. Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma. New York: Hill & Wang, 2004.

Wood, Peter H. Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion, reissue ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996.