4

The Coming of Independence

Many of the most recognizable Founding Fathers owned African American slaves. Most of the major southern Founders did, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. Even Benjamin Franklin owned some slaves for much of his life, though at the end of his career he became involved with the antislavery movement. Some of the slave-owning founders such as the brilliant Virginia orator Patrick Henry openly admitted that slavery contradicted the ideals of the American Revolution. But that admission did not typically lead to action against slavery.

Massachusetts patriot soldier Lemuel Haynes did not attempt to reconcile slavery and the American Revolution. Haynes, the child of an African American father and white mother, had no doubt that slavery was wrong. Haynes had never been a slave, but he had worked as an indentured servant. This gave him enough of a taste of the “miseries of a slave” to know that it could be “a hell on earth.” When the Revolutionary War broke out in the mid-1770s, Haynes joined the Massachusetts militia first and then America’s national army, the Continentals. About the same time, Haynes experienced a dramatic conversion as he accepted Christ for salvation.

Haynes fell under the influence of New England ministers who were the successors of Northampton’s Jonathan Edwards, who had died in 1758 shortly after becoming the president at the College of New Jersey in Princeton. Haynes started training to become an evangelical pastor. The combination of evangelical and revolutionary ideas gave Haynes a powerful vocabulary with which to denounce slavery. After the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence, Haynes seized upon the notion that “all men are created equal” to frame his essay “Liberty Further Extended.” In it Haynes proclaimed that liberty was a jewel as precious to blacks as to whites. Before God all people stood equal, and they all found bondage equally revolting. During the revolutionary crisis the Founding Fathers routinely warned that the British authorities were trying to turn them into economic pawns, or “slaves.” Haynes and other American critics of slavery reminded the nation that many hundreds of thousands of Americans already knew the denigrating depths of real chattel slavery. Taxation without representation was a legitimate complaint, but did actual slaves not suffer much worse?

French and Spanish Expansion

In mainland North America, the long-term rivalry between the French and the British had to resolve before the tensions between Britain and its colonists could come to the fore. Although French settlement in America never matched the population of the English colonies, the French presence in America and the Caribbean continued to grow in the 1700s. The French island of Saint-Domingue (or Hispaniola, the island shared today by Haiti and the Dominican Republic) became the Caribbean’s largest sugar producer and the world’s largest coffee grower. Its plantation masters imported almost 400,000 slaves between 1680 and 1730. The French also founded new settlements in the Great Lakes region, including Fort Detroit in 1701. On the Gulf Coast they founded New Orleans in 1718.

Figure 4.1. Lemuel Haynes.

The Spanish also slowly expanded into the American Southwest, returning to New Mexico in the 1690s after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. They founded the presidio (fort) and Catholic mission at San Antonio, Texas, in 1718. The farther the Spanish moved into Texas, however, the more risks they faced from the Comanches, arguably the most formidable Native American power on the continent. The Comanche “empire” centered on the grasslands of what would become northwest Texas. The Comanches depended heavily on horses, which Europeans had only introduced to the continent in the 1500s. They played Spanish and French officials and traders off each other, and in a sense they played the role of the dominant imperial power against the weaker European settlements. That regional Comanche dominance continued well into the nineteenth century. In the mid-1800s, the Comanches finally fell victim to waves of epidemic disease, the decimation of buffalo herds, and growing pressure from the United States government to move them onto reservations.

The creation of New Orleans near the mouth of the Mississippi River split Spain’s North American colonies of Texas and Florida in two. Both the Spanish and the British viewed France’s expansion warily. New Orleans’s location with regard to empire and the river made strategic sense, even if it was (and has ever since been) not an ideal location in terms of flood risk. When the Mississippi flooded in 1719, much of New Orleans stayed underwater for six months. The city has since made a variety of efforts to build flood-control levees. But the levees did not prevent Hurricane Katrina from devastating New Orleans in 2005, in what became the costliest natural disaster in American history to that point.

Once the 1719 flood waters subsided, New Orleans in the 1720s became a village dependent on slavery. Louisiana slaves grew tobacco and rice, moved goods up and down the Mississippi, and helped dig New Orleans’s first dams and canals. The Louisiana colony in 1724 adopted the Code Noir to help regulate the slave system, taking many cues from earlier laws adopted in Saint-Domingue. As in the British colonies, slaves who ran away or who committed violence against whites could face gruesome retribution. At the same time, the Code Noir enjoined Catholic priests and planters to provide Christian instruction for the slaves. Authorities formally frowned on sexual relationships between French settlers and Africans, but they generally ignored the common intermarriages of the French and Native Americans in Louisiana. French-Indian unions seemed to help strengthen trade and diplomatic alliances.

The Seven Years’ War and the Contest for Empire

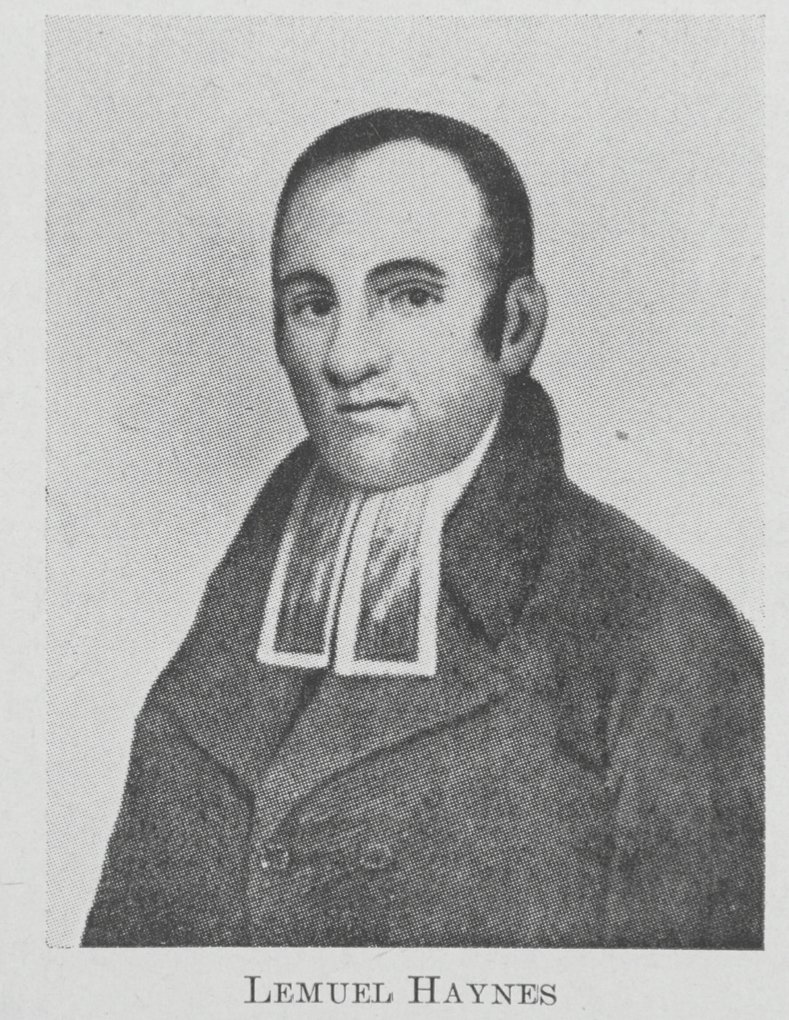

With French settlement extending from Quebec in the northeast to Fort Detroit in the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi to New Orleans, the British colonists had the distinct impression that the French were trying to encircle them. Areas such as the Ohio River Valley region in western Pennsylvania became among the most disputed grounds between the two powers, leading to George Washington’s 1754 expedition and defeat as well as the rout of British general Edward Braddock’s army in 1755. Even as Washington was struggling to stave off the French in 1754, British colonial officials met in Albany, New York, to foster concerted colonial action against the French. At this “Albany Congress,” Benjamin Franklin proposed a plan of union that would have created a new intercolonial government headed by a royally appointed president. This government could more effectively act against military threats that faced all the colonies. Although Albany delegates liked the plan, it met with little support in the colonial assemblies or in London. The colonies did not wish to give up their individual powers, while some in England feared giving the colonies a way to act as one. Who knows what impact it might have had on the unfolding of the American Revolution if the Albany Plan had been adopted?

After Braddock’s defeat, Protestant Britain and Catholic France declared war on each other in 1756. Although the fighting in the war began in 1754, the Seven Years’ War formally lasted from 1756 to 1763. It was arguably the first truly global war in human history, with battles transpiring in North and South America, the Caribbean, Europe, and Asia. In the opening years of the war in North America, the French brought many more troops into their campaigns than did the British. They also successfully convinced many Indian tribes to join them in the fight (thus the “French and Indian” War). In 1757, a large French force, assisted by thousands of Native Americans, besieged Fort William Henry, a British installation in upstate New York between Albany and Montreal, Canada. When the fort fell after a week’s bombardment, the French commander, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, offered the British troops conventional terms of surrender. But the Indian fighters, according to their typical wartime practices, expected to take booty and captives. That misunderstanding led to the Fort William Henry “massacre.” Even as French troops sought to stop them, Indians tomahawked some of the surrendering British soldiers as well as women, children, and black slaves and servants who lived in the fort. Nearly 200 of the British at Fort William Henry died in the episode, and another 500 were seized as prisoners. The native allies of the French were still angry about the episode. They wondered why they should keep helping the French if they were not allowed to take the full spoils of war. Fort William Henry was a turning point in the war because many Native Americans abandoned the French. The incident inflamed British resentment against the French and their remaining Native American allies.

After Fort William Henry, William Pitt became the new leader of the British administration in London, and he vowed to put maximum effort behind the war effort in America. He took out massive loans and raised taxes in Britain to fulfill this promise. The second half of the war would see major improvements in Britain’s American campaigns and also in the American domestic economy. In 1758, the British, with George Washington participating again, conquered Fort Duquesne in western Pennsylvania. The British renamed it Fort Pitt, or Pittsburgh. The key clash of the North American war was the Battle of Quebec in 1759, when the British conquered the center of French power on the continent. British general James Wolfe faced off with the French general Montcalm, the commander in the siege of Fort William Henry. Quebec City had some of the most formidable defenses on the continent, so Wolfe devised a plan by which he would take thousands of troops past the city’s cannons under cover of darkness and scale high cliffs to get to the opposite side of the city at a lightly guarded area called the Plains of Abraham. The next morning the normally steady Montcalm panicked at the unexpected sight of Wolfe’s army and ordered his troops to leave the city’s walls and attack the British. Wolfe and Montcalm both died in the assault, in which the British easily defeated the French. Soon the great citadel of French Canada fell to the British army. A year later, so did Montreal, sealing France’s fate on the North American mainland.

Figure 4.2. This political cartoon (attributed to Benjamin Franklin) encouraged the American colonies to join the Albany Plan for Union. From the Pennsylvania Gazette, May 9, 1754. Abbreviations used: South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and New England. This is a somewhat odd division: New England was four colonies, and Delaware and Georgia are missing.

After the fall of Canada, most of the fighting shifted to the Caribbean, where the French, their Spanish allies, and the British fought for control of the sugar islands. British ships laid siege to Havana, Cuba, in summer 1762. Havana was the hub of Spain’s Caribbean traffic in slaves, sugar, and silver. The siege climaxed in a remarkable British plot in which they dug a tunnel underneath Havana’s central fortress and exploded it by surprise. Havana’s fall to the British was the Spanish Caribbean’s equivalent of Quebec’s defeat in Canada. America’s British colonists rejoiced at the defeat of the twin powers of Catholicism.

European negotiators brought a formal end to the Seven Years’ War with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. France and Spain were able to regain some of their valuable Caribbean holdings in exchange for ceding territories in mainland North America east of the Mississippi River. In particular, France gave up its claims to Canada. In arrangements seeking to restore a balance of power in the Western Hemisphere, France gave up New Orleans and the vast Louisiana Territory to Spain. But now Britain controlled Canada and what would become the eastern half of the United States. (The negotiators did not consult Native Americans who lived in many of the territories in question.) In 1763, the new American nation was still not in view, as most colonists were delighted with the outcome of the war. If anything, British patriotism was at its apex among the colonists in 1763, with some predicting that the British empire in America would continue to flourish for centuries to come under the blessing of God. Massachusetts pastor Thomas Barnard exulted, “Here shall our indulgent Mother [Britain], who has most generously rescued and protected us, be served and honored . . . till time shall be no more.”

The British Empire and the Seeds of Revolution

If 1763 was the height of British patriotism in the colonies, how did the colonies descend into revolution against Britain a mere twelve years later? The seeds of the revolution were planted in the British government’s attempts to balance its budget and to consolidate its gains in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War. The war had settled the imperial status of eastern North America, but it destabilized Britain’s relationship with Native Americans. Many Indians had been aligned with the French, even after Fort William Henry, and the French surrender threw the American interior into turmoil. British officials assumed that since the French were gone, they no longer needed to provide extensive supplies of gifts to Native Americans to maintain a favorable relationship. But Indians took the cessation of gifts as a violation of long-standing agreements. In 1763, Indians attacked a string of British forts from western Pennsylvania to Lake Michigan. Historians usually call this episode “Pontiac’s Rebellion,” named for the influential Ottawa Indian leader who worked to unify a number of tribes against British power. The rebellion faltered due to poor supplies, disease, and the British decision to renew gift giving and more generous trade practices. Pontiac died in the Illinois territory in 1769, murdered by a Peoria Indian.

Indians and British colonists both committed outrages, especially in unstable frontier regions. In late 1763, vigilantes called the “Paxton Boys” set upon a group of Conestogas in eastern Pennsylvania. Even though the Conestogas were Christian converts and uninvolved with the frontier violence, the Paxton Boys showed them no mercy, murdering, scalping, and burning six people. Authorities tried to protect other Conestogas in a Lancaster, Pennsylvania, jail, but the Paxton Boys broke in and killed fourteen more, including eight children. Hundreds of men then marched on Philadelphia, looking for more Indians, but colony officials and British troops put down the murderous uprising. Benjamin Franklin took a great deal of political heat when he denounced the Paxton Boys as “Christian White Savages.”

Pontiac’s Rebellion helped convince the British administration that they needed to maintain a strong military presence in the colonies and that they should stem the flood of American colonists pouring across the Appalachians in order to avoid lawlessness and conflict with Indians. In a widely ignored dictate, the Proclamation of 1763, British officials prohibited colonial settlement beyond the Appalachian Mountains. As with so many British regulations, the colonists had become accustomed to a lack of enforcement. Many land seekers just kept crossing the mountains into the Ohio country.

The primary British concern following the Seven Years’ War was the national debt, which had ballooned during the conflict. Not only had the war been enormously expensive, but keeping part of the British army stationed in America promised even more costs and debt. Different officials would offer a range of financial and tax plans into the mid-1770s to address the crisis, but Britain’s young King George III tended not to maintain the same administration for long. The first strategy came from finance minister George Grenville, who in 1764 devised the Sugar Act. Grenville designed this act to crack down on the common colonial practice of smuggling molasses. The Sugar Act lowered the trade duty (or tax) on molasses but put measures in place to require colonists to pay it. It also placed new duties on goods such as coffee, wine, and sugar. Some Americans such as Benjamin Franklin thought the new measures were warranted. But the Sugar Act precipitated some grumbling in the colonies. James Otis of Massachusetts wrote that Parliament had no right to tax the colonists. Drawing on John Locke’s theory of government, Otis insisted that if anyone could tax him without his consent, then “he deprives me of my liberty, and makes me a slave.” Otis and other patriots began to develop the theory that only a people’s elected representatives could justly wield the power to tax.

“No Taxation without Representation”

The slogan “no taxation without representation” gets to the heart of the disagreement between Britain and the colonies. The British administration took the view that the colonists were represented in Parliament, even though the colonists did not actually elect members of Parliament. Historians call this a theory of virtual representation. British officials noted that few people in Britain could actually vote for Parliament, either. Women, children, poor men, and many others could not vote in British elections, yet Parliament was bound to look out for the interests of all British people. That included the colonists. But the property-owning men who championed the revolution did not accept the concept of virtual representation. They wanted actual representation. Few people imagined that America would ever send representatives to Parliament, if for no other reason than the difficulties of transatlantic travel and communication. And the patriots acknowledged that at some level governments needed the power to tax in order to raise revenue. But they argued that taxation was such a dangerous power it threatened the rights good government was supposed to protect. In Locke’s theory these basic rights included life, liberty, and property. The patriots contended that they would be willing to pay taxes but only those passed by their own representatives in the colonial legislatures. If those local taxes were unjust, then the people could vote the legislators out of office.

British officials and rebelling colonists would never resolve this fundamental disagreement about the powers of government. The furor over the new taxes went to greater heights with the adoption of the Stamp Act (1765), which taxed many kinds of printed goods and legal documents in the colonies. While the effects of the Sugar Act filtered down slowly to regular American consumers, the Stamp Act touched many American families directly. Printers were most immediately affected by the tax, and they were also in the best position to lodge protests against it. The Stamp Act roused protests across the colonies, not least in Virginia. There, Patrick Henry introduced inflammatory resolutions against the act. Newspapers added other resolves to Henry’s list that were even more extreme than those he actually introduced. In Henry’s speech attacking the Stamp Act, he suggested that friends of liberty had always risen up to confront tyrants, whether Brutus against Caesar, or Cromwell against King Charles I. The implication was clear: Henry was saying that if King George III did not back off, someone might try to assassinate him. Although it would take a full decade before most Americans were prepared to reject the king’s authority, radical statements like these began to erode the crown’s authority in the colonies.

Supporters of the Stamp Act faced intimidation and vandalism in the colonial cities as the date approached for the tax to go into effect. In August 1765, a Boston crowd ransacked the homes of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson and the appointed stamp agent, Andrew Oliver. Resistance organizations called the “Sons of Liberty” organized some of the protests and encouraged colonists to boycott British goods as long as the Stamp Act remained in effect. Representatives from nine colonies met in New York City in October 1765 to frame an intercolonial response to the crisis. This “Stamp Act Congress” was the first meeting of its kind since Ben Franklin’s failed Albany Congress in 1754. The delegates took a respectful, conciliatory tone but still affirmed that only their elected representatives had the power to tax them. The combined effects of the formal and informal protests against the Stamp Act made it unenforceable. By November 1765, those responsible for enforcing the act had either resigned or had stopped appearing in public.

Changes in the British administration and pressure from British merchants signaled the end of support for the Stamp Act in London, too. Parliament summoned Ben Franklin, who was serving as an agent for Pennsylvania in London, to testify about the effects of the act. Franklin had suffered serious political damage for originally supporting the act, but his dazzling testimony redeemed him in the eyes of many patriots. “What was the temper of America toward Great-Britain before the year 1763?” members asked him. Franklin said, “The best in the world. They submitted willingly to the government of the Crown, and paid, in all their courts, obedience to acts of parliament. Numerous as the people are in the several old provinces, they cost you nothing in forts, citadels, garrisons or armies, to keep them in subjection. They were governed by this country at the expense only of a little pen, ink and paper. They were led by a thread.” The interrogation continued:

MP: “And what is their temper now?”

Franklin: “O, very much altered.”

MP: “Don’t you think they would submit to the stamp-act, if it was modified, the obnoxious parts taken out, and the duty reduced to some particulars, of small moment?”

Franklin: “No; they will never submit to it.”

Parliament was convinced that the Stamp Act had been a tactical mistake, so they repealed it in 1766. But they were not convinced by the colonists’ constitutional arguments about the power to tax. They added a “Declaratory Act” to the repeal, which asserted that they had “full power and authority to make laws . . . to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the Crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever.”

The Declaratory Act signaled that Parliament still intended to bring the colonies in line. Parliament still needed to address Britain’s massive national debt by imposing new taxes. Prime Minister Charles Townshend in 1767 devised the Townshend Revenue Acts, which placed import fees on goods such as paper, glass, and tea. American resistance to Townshend’s duties focused on boycotting British goods through nonimportation and nonconsumption agreements. These campaigns sought to mobilize American merchants as well as regular consumers, both female and male. Women often made day-to-day purchasing decisions related to household needs of food and clothing. They would also have to find ways to replace goods they declined to purchase from British importers. Making homespun clothing became a political statement and a sign of solidarity with the patriot resistance. The leader of the Sons of Liberty in Charleston, South Carolina, admitted that the key to the boycotts was “to persuade our wives to give us their assistance, without which ’tis impossible to succeed.” In Middletown, Massachusetts, 180 women produced more than 20,000 yards of cloth in 1769 alone. A pro-British critic lamented that even the pastors of New England encouraged “manufactures instead of the Gospel.” At the ministers’ behest, women and children “set their spinning wheels a whirling in defiance of Great Britain.”

American colonists were drawing on a set of ideas historians call republicanism to interpret what was going on in the crisis with Britain. Republicanism has meant many things throughout American history. At its core, republicanism was a belief that government should protect people’s liberties and that government itself was often the greatest threat to liberty. Republicanism had sources ranging from Greek and Roman antiquity, the Bible, the Renaissance, and British political opposition writers in the eighteenth century. In the classical theory of republics, the most virtuous, independent men of a society should govern because they were the best prepared to serve the public good. But when politicians and bureaucrats became corrupt—as they always did eventually—they would pursue conniving strategies to deprive the people of their liberty and to turn them into economic pawns. Republican thought complemented the biblical notion that people were not naturally good. If left unchecked, officeholders would inexorably abuse their power. Republicanism could feed a conspiratorial mind-set. Sometimes those influenced by republican thought assumed the worst about their enemies’ motives.

Republicanism accounts for the vast gulf between the patriots’ view of the tax programs and those of the British administration. The administration knew Britain had incurred huge expenses in defending the colonists from the French and Spanish during the Seven Years’ War, so they assumed the colonists needed to do their fair share to shoulder the financial burden. Patriots saw the tax programs as an ominous threat to their fundamental liberties. Some colonists admitted the taxes imposed were not that burdensome in and of themselves. But as one correspondent told Ben Franklin in 1769, “From what they have already done the colonies see that their property is precarious and their liberty insecure. . . . The very nature of freedom supposes that no tax can be levied on a people without their consent.” Resistance leaders believed that if they did not stand up against the first encroachments on their liberty, they would eventually find that they had lost too much power to resist any longer.

Nothing was more ominous in the colonists’ view than the British decision to move 4,000 regular soldiers into Boston in 1768. Republican political theory held that “standing” armies (that is, peacetime armies) were a sign of rising tyranny. Why do you need such a huge army—one soldier for every four civilians—if there was no war going on? colonists wondered. Boston minister Andrew Eliot exclaimed in 1768, “To have a standing army! Good God! What can be worse to a people who have tasted the sweets of liberty!” Bostonians such as the impoverished shoemaker George Robert Twelves Hewes found the military occupation annoying on a daily basis. Once, the soldiers stopped Hewes at night and would not let him go until he gave them some of his rum. Another time he saw a soldier rob a woman of a bonnet and other fancy items. Hewes and other working-class people in Boston viewed the soldiers as more competition in the town’s already-tight labor market, as the troops would do odd jobs in their off hours.

Reverend Eliot predicted that the British occupation of Boston would end in bloodshed. He was right. A series of violent altercations between soldiers and civilians finally culminated in the Boston Massacre of March 5, 1770. A fight broke out between a heckling crowd and a British sentry at a Boston customhouse, with the Bostonians pelting the soldier with snowballs and chunks of ice. Confusion descended on the street with some shouting (perhaps mischievously) that a fire had broken out. The British commander sent in more troops to protect the sentry, and in the chaos the soldiers opened fire on the crowd. Eleven Bostonians were hit; five eventually died. One of the dead was Christopher (Crispus) Attucks, a forty-seven-year-old man of African and Native American descent, who may have been a runaway slave. John Adams called Attucks the first “martyr” of the American Revolution. Boston silversmith Paul Revere produced a popular engraving of the shooting that reflected the bloody scene, lamenting how the city’s “hallowed walks” were now “besmeared with guiltless gore.”

The Boston Massacre might seem like a perfect catalyst for the outbreak of war, but it actually signaled the end of the first major stage of the revolutionary crisis. To assuage tensions, the British withdrew their troops from the city, housing them at Castle William in Boston Harbor. The British administration also decided in 1770 to repeal the Townshend Acts, except for a duty on tea. For about three years the colonies were at relative peace, but the basic constitutional question about taxes and political power remained in place. Patriot radicals kept reminding colonists of the danger that remained. Samuel Adams, a distant cousin of John Adams, had briefly and unsuccessfully worked in his father’s beer business before entering Massachusetts politics. Alarm over increasing royal authority in the colony led him to propose the creation of a “committee of correspondence” in 1772, which would “state the rights of the colonists and of this province in particular, as men, as Christians, and as subjects,” and “to communicate and publish the same to the several towns in this province and the world.” Other colonies would adopt Adams’s concept, and the committees of correspondence became key organizations for patriot strategizing.

Figure 4.3. Engraving of the Boston Massacre perpetrated in King Street Boston on March 5, 1770.

Tea Party

The second, more acute phase of the revolutionary crisis began in 1773 with the passage of the Tea Act. The controversy over the Tea Act was much more complicated than what many Americans may assume today. The act did not raise a new tax on tea. Instead sponsors meant for the act to bail out the powerful but struggling East India Company by reducing the tax on tea and allowing East India agents to sell tea directly to American consumers. This would make the tea cheaper for Americans, who had become accustomed to buying tea smuggled into the colonies from other sources. So what was the problem? First, the Tea Act cut out many colonial middlemen in the tea trade, depriving them of a major source of income. Also, the British named only a few tea agents, all of whom had demonstrated loyalty to royal authority. Finally, the tea tax paid in American ports (though not British ports) remained in effect. Patriots saw the Tea Act as an attempt to get Americans to accept the idea that Parliament could legitimately tax them. A Philadelphia newspaper thundered that Americans were “not ready to have the yoke of slavery riveted about their necks” and vowed to “send back the tea from whence it came.” Indeed, in Philadelphia and New York, menacing patriots were able to stop the East India ships from unloading their cargo and sent them away.

In Boston, governor Thomas Hutchinson, though a native of the city, was stridently committed to royal power in Massachusetts. Hutchinson wanted Bostonians to obey the Tea Act. He insisted that they allow the tea to be unloaded. Samuel Adams and other Boston patriots began holding massive resistance meetings once the first tea ship arrived. When it became clear that Hutchinson was going to force the unloading of the tea, Adams prompted a mob of dozens of men to take action. They dressed “in the Indian manner” and blackened their faces. Shoemaker George Robert Twelves Hewes recalled how he stepped into a blacksmith’s shop on the way to the ship to rub soot on his face. Then he borrowed a blanket to wrap around himself. One blacksmith’s apprentice in the crowd thought they all looked like “devils from the bottomless pit, rather than men.” The tea rioters boarded the ships, smashed open 340 chests of tea, and dumped their contents into Boston Harbor. The tea would have been worth about £10,000.

Britain responded to the Tea Party with the harshest measures yet: a set of laws called the Coercive Acts. King George III said that “the colonists must either submit or triumph.” One of the Coercive Acts was the Boston Port Bill, which closed the city’s port to all commercial ship traffic. The Massachusetts Government Act dramatically reworked the frame of the province’s government, putting much more power in the hands of royal appointees. In response, a shadow patriot government, the “Massachusetts Provincial Congress,” began meeting in defiance of the law. Another 1774 bill, the Quebec Act, was arguably the most provocative of all. It permitted the free practice of Roman Catholicism in Quebec (which the British had conquered in the Seven Years’ War) and extended Quebec’s southern boundary to the Ohio River. In the midst of the tension between Britain and the colonists, this opened a new front of suspicion: the fear of a Catholic conspiracy against Protestant Americans. American anti-Catholic belief had hardly died with the end of the Seven Years’ War. Young Alexander Hamilton, a student at King’s College (later Columbia University) in New York City, spoke for many when he wrote that the Quebec Act was designed to promote “arbitrary power, and its great engine, the Popish religion.” Few would argue that the American Revolution was a war of religion, but controversies like that over the Quebec Act led some patriots to speculate that dark spiritual forces were behind the attack on the colonists’ liberties.

Figure 4.4. Boston Tea Party by W. D. Cooper. Illustration for The History of North America. London: E. Newbury, 1789.

The Continental Congress

The patriots called the Coercive Acts the “Intolerable Acts.” But since much of the laws’ punitive force fell on Massachusetts, 1774 represented a critical time for the rest of the colonies. Certainly other colonies had shown some radical patriot tendencies, but would they come to Massachusetts’s defense? Many colonists were appalled at the harsh measures and realized that if the British administration could shut down the legitimately elected government of Massachusetts, any of the other colonies could be next. The patriot committees of correspondence began to call for a colonies-wide convention to discuss resistance tactics. All of the colonies except Georgia responded by sending delegates to the Philadelphia meeting of the First Continental Congress in September 1774. This brought together for the first time some of the colonies’ political luminaries, including John and Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, and George Washington. It was the first sign of Americans taking on governmental functions on a national scale. But few were yet willing to discuss rebellion or independence openly.

As they would be for the next twenty-two months before independence, the patriots at the Continental Congress were divided between radicals and moderates. Some, especially Samuel Adams, wanted to escalate resistance, while moderates wanted to avoid further provocations. Adams and the Massachusetts delegates won a victory when the Congress endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, brought from Massachusetts to Philadelphia by Boston patriot leader Paul Revere. The Resolves demanded that the Coercive Acts should be “rejected as the attempts of a wicked administration to enslave America.” They further agreed that the Quebec Act was “dangerous in an extreme degree to the Protestant religion and to the civil rights and liberties of all America; and, therefore, as men and Protestant Christians, we are indispensably obliged to take all proper measures for our security.” The Resolves encouraged military preparations for self-defense and a cessation of all commerce with Britain.

The Congress also adopted a Declaration of Rights, which drew on Lockean political theory to assert that the colonists were “entitled to life, liberty and property.” They should enjoy the same rights and liberties as Britons living in the mother country, they said. They would not give up taxes without giving their consent through elected representatives. The Congress went much further than merely stipulating rights, however, when it created the “Association,” a system for enforcing commitment to nonimportation and nonconsumption. This was the Congress’s first major act of governing the colonies. They committed to enforce the cessation of traffic in a host of products, including tea, wine, coffee, molasses, and most conspicuously, slaves. In the chattel system, stopping the importation of slaves could hurt British merchants as much as boycotting any product.

The Congress called for local Association committees to watch out for violators of Association policies and to publicly shame them as “enemies to American liberty.” When these committees went into action, they effectively became an alternative patriot government in many American towns. Some 7,000 men served on Association committees across the colonies. As in earlier phases of resistance, women participated by refusing to buy British products, arranging for substitutes for those products, and helping humiliate violators of the Association. Sometimes those who refused to comply with the regulation suffered tarring and feathering, which might seem like a quaint punishment but could cause horrific burns on the victim’s body. One pro-British violator in Connecticut was forced to walk twenty miles between towns, all while carrying a goose. He then had to pluck the goose before a hooting crowd before having tar poured over him and then being covered with the feathers he had just plucked. The mere threat of such punishments was enough to bring many reluctant Americans in line with the patriot cause.

Liberty or Death

Observing the unfolding resistance, King George III said that “blows must decide” whether the colonies—particularly New England—would be subject to England or independent. As he had done ten years earlier, Patrick Henry of Virginia helped set the radical tone of the crisis. Having recently returned from the meeting of the First Continental Congress, Henry in March 1775 reacted to a proposed petition for relief that some Virginia Convention members wished to send to Parliament. A disgusted Henry declared that the time for petitioning was over. Virginia, and all the colonies, should begin forming militias to prepare for war, he said. In his short “Liberty or Death” speech, Henry included many allusions to the Bible to emphasize the sacredness of the patriots’ cause. He concluded with a thunderous call to arms: “It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace—but there is no peace. [Here he referenced Jer 6:14.] The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? . . . Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God!” With this Henry raised his arms and proclaimed, “I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

As Henry had predicted, war did begin in Massachusetts less than a month later. Thomas Gage, the royal military governor of the province, had received instructions from Britain to snuff out hopes of patriot military resistance. So when Gage sent British soldiers (the “redcoats”) to capture Massachusetts militia supplies held in Concord, patriot sentinels, including Paul Revere, began to alert the countryside surrounding Boston. Unlike the old legend of Revere’s midnight ride, he almost certainly did not tell the patriots that the “British are coming!” The colonists still considered themselves British, so he probably said, “The redcoats are coming!”

In response to the sentinels’ warnings, Massachusetts militiamen (an assortment of farmers, old men, and boys, most with little to no military experience) gathered on the town green of Lexington, Massachusetts, during the night of April 18–19, 1775. Early on the morning of the nineteenth, redcoats arrived on their way to Concord and ordered the militia to disperse. They did not; the two sides began arguing with and insulting each other. Finally, a shot rang out. Americans have often called this the “shot heard round the world,” as it signaled the beginning of the American Revolution. We will never know who shot first, but in response the British soldiers fired a volley against the Massachusetts men, killing eight of them.

Figure 4.5. Give me liberty, or give me death! Patrick Henry delivering his great speech on the rights of the colonies before the Virginia Assembly, convened at Richmond, March 23, 1775, concluding with the above sentiment, which became the war cry of the revolution.

The Early Battles

From Lexington the redcoats moved on to Concord, where more Massachusetts militia, called “minutemen,” had assembled. A strong American stand at Concord’s North Bridge convinced the redcoats to begin retreating to Boston. The sixteen-mile trek turned into a deadly gauntlet for the redcoats. The whole surrounding country seemed to know what had happened at Lexington and Concord, and now militiamen and farmers shot at the redcoats from behind rocks, trees, fences, and out of windows. The shocked British sustained heavy casualties on the chaotic march back to Boston. Hundreds were wounded, missing, or dead. This battle was unlike most of the Revolutionary War clashes, in which the two sides typically faced each other in formal array. Nevertheless, the retreat from Concord gave the British army a taste of one of their most difficult challenges: how to subdue not just an opposing army, but a revolutionary people.

One of the reasons few Americans were eager to declare independence in 1775 was that there was no independent military structure, which would be required for Americans to fight a war. But the (Second) Continental Congress began building an American national military, appointing Virginia’s George Washington as the general over the Continental Army in June 1775. Washington was distinguished and admired, with decades of military experience dating back to the beginning of the Seven Years’ War.

Coincidentally, just days after Congress chose Washington to lead the American fight, Massachusetts militiamen engaged the British in the first large-scale clash of the Revolutionary War, the (misnamed) Battle of Bunker Hill. Most of the action took place on Breed’s Hill, next to Bunker Hill, in Charlestown, Massachusetts, north of Boston. The militia had seized these strategic hills in hopes of bombarding British positions in occupied Boston. An evangelical chaplain, David Avery, saw his first action at Bunker Hill, just like many of the Massachusetts troops. But as British forces crossed the Charles River and began to ascend Breed’s Hill, Avery stood on top of Bunker Hill, arms raised and praying for the American soldiers. The patriots repulsed the first two British assaults, but when the British pressed against the American position for a third time, the patriots began to run out of ammunition. This was why the American commander reportedly told his men not to “fire until you can see the whites of their eyes.” Some of the militiamen were reduced to fighting without bullets, using bayonets or their fists. Eventually the British overran the Massachusetts soldiers, who retreated. But the British suffered awful losses, with more than a thousand casualties. David Avery wrote that, even though the British technically won the battle, God had been the Americans’ “rock and fortress: he covered our heads with a helmet of salvation.”

Even after Bunker/Breed’s Hill, the Continental Congress remained conflicted about how to handle the controversy. Did any chance of reconciliation remain? The Congress sent the king the “Olive Branch Petition” in July 1775, imploring him to enter negotiations with the colonists. The king dismissed the petition out of hand and instead declared that the patriots had already engaged in “rebellion and sedition” against Britain. By the beginning of 1776, many Americans had concluded that, as Abigail Adams told writer Mercy Otis Warren (the sister of early patriot leader James Otis), “The die is cast. . . . The sword is now our only, yet dreadful alternative.” All that was left to do, Adams wrote, was to make “penitent supplications to that Being who delights in the welfare of his creatures, and who we humbly hope will engage on our side.”

Declaring Independence

Even for those who had concluded that a major war was at hand, declaring independence remained a fearsome prospect. Although the colonies were more diverse than Britain, white colonists largely considered themselves to be British. Most spoke English and understood history, politics, religion, and literature from a British perspective. Particularly outside of New England, great numbers of Americans had received baptism in the Church of England and associated their rituals of birth, marriage, and death with that denomination. Anglicans prayed for the king as part of their regular Sunday services. Regardless of the troubles over taxes, many merchants’ and politicians’ fortunes were tied directly to Britain. It was not easy culturally, politically, or financially to consider severing that tie with the home country.

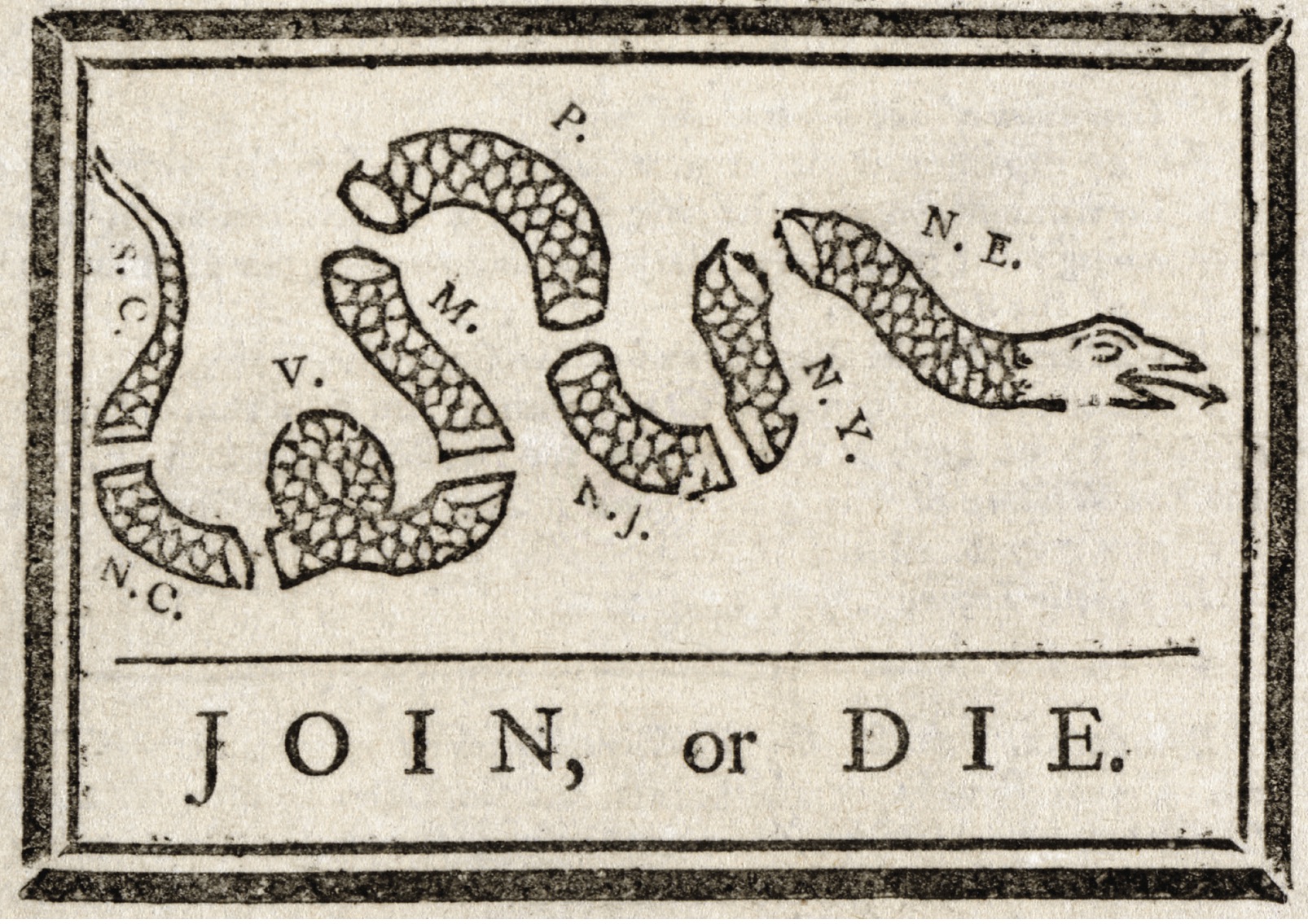

The turning point in shifting America’s discussion from resistance to independence was the publication of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in early 1776. This best-selling pamphlet became arguably the most important political essay in American history. Few publications have ever so deeply influenced the course of debate on such a momentous issue as independence. In gripping prose, Paine made the case for rejecting King George III and launching a new nation. Few had ever dared to speak contemptuously of the king in this deferential society, but Paine called him the “Royal Brute of Great Britain.” Paine would later become known as the most notorious anti-Christian skeptic in America, but Common Sense hinged on the idea that monarchy had never been God’s will. Paine directed colonists to 1 Samuel 8, where God had tried to convince unruly Israel that they did not really want a king, for a king would abuse them. Paine concluded that monarchy was a kind of political original sin. Now Americans had a chance to “begin the world over again.” George Washington noted in April 1776 that, based on correspondence he was receiving from Virginia, “Common Sense is working a powerful change” in the minds of many.

Across America, dozens of towns and entire colonies began declaring themselves independent from Britain in the spring and summer of 1776. In June the Continental Congress formally took up the question of independence themselves. Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee moved that the “United Colonies” declare themselves to be “free and independent states.” But Congress still needed another month to deliberate this epochal move. Finally, on July 2, they approved Lee’s motion. It was fifteen months since the battles of Lexington and Concord had happened, showing just how hard it had been for colonists to part ways with the mother country. Fighting against the fearsome British military was one thing; independence was another.

John Adams thought July 2 should be remembered as America’s national day of independence. Instead, we remember July 4, the day Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson of Virginia was the lead author of the Declaration, working with a committee that included Adams and Benjamin Franklin. The Congress also edited the Declaration, deleting an awkward section in which Jefferson blamed the British government for forcing slavery in the colonies and for vetoing colonial efforts to limit the slave trade. The Declaration still made an oblique reference to slavery, in its complaint that the king had “excited domestic insurrections amongst us.” This was a reference to an offer made in late 1775 by Virginia’s royal governor, who promised freedom to any slave or indentured servant who agreed to serve in the British army against the patriots. Nothing the British could have done in the South would have upset colonial slave owners more than this proclamation. The anger it generated was a critical step toward independence, even before Paine published Common Sense.

The Declaration of Independence came from a classic American combination of sources: “Enlightenment” rationalism, John Locke’s political ideas, classical republicanism, and the proposition that our rights come from God. The critical passage began in the second paragraph, which asserted the “self-evident” truths that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Here we see the action of God in creating people and endowing them with basic rights. No government or ruler could rightly deprive people of those rights because of our equal standing before God. Locke had identified life, liberty, and property as the basic rights government was meant to protect, but “pursuit of happiness” seemed to include more than just the acquisition of property. If there was any doubt about the British administration’s intentions in the tax programs, the Declaration asserted (in a line illustrating classical republicanism’s fear of the loss of liberty) that they evinced “a design to reduce [the people] under absolute Despotism.”

Figure 4.7. The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, by John Trumbull. Trumbull’s painting represents the presentation of the Declaration of Independence to the Continental Congress. The painting, which took decades to finish, pictures all of the members of the Committee for drafting the Declaration and attempts to include all of the delegates to Congress, though Jefferson was responsible for the majority of the Declaration and some of the delegates did not support independence.

Jefferson then included a lengthy list of the king’s violations of the colonists’ rights. Among them were depriving the colonists of their right to make laws for themselves, keeping a standing army and forcing the colonists to house British soldiers, and “imposing Taxes on us without our Consent.” Expressing bitterness over the British alliance with many Indians, the Declaration lamented that the king had “endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” The Declaration concluded by committing to “a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence,” and mutually pledging to one another “our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

The idea that “all men are created equal” has echoed down through American history, functioning as an American creed. Yet from the day Congress adopted the Declaration, people have questioned what it means and what “equality” requires. Soldier and pastor Lemuel Haynes and other African Americans were among the first to question how America could accept slavery if all men were created equal. (Most people would have agreed that this notion of equality by creation applied to all people, regardless of race or ethnicity, since most accepted the idea of a single origin point of humanity, typically the creation of Adam and Eve in the book of Genesis.) Women also began to wonder if they did not somehow fit into this equation, since God had created both male and female in his image. But there were no easy answers to these questions since chattel slavery and the legal advantages of men over women were deeply rooted in American society. Yet the Declaration of Independence had set a clear standard for human equality, based on our common creation by God. Americans would spend much of their subsequent history fleshing out the implications of equality by creation. In the short term, however, they had a war against Britain to fight and a new nation to form.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Fred. The War That Made America: A Short History of the French and Indian War. New York: Penguin, 2005.

Carp, Benjamin L. Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Dowd, Gregory Evans. War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, and the British Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Fischer, David Hackett. Paul Revere’s Ride. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Foner, Eric. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Gross, Robert A. The Minutemen and Their World. New York: Hill and Wang, 1976.

Kidd, Thomas S. God of Liberty: A Religious History of the American Revolution. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

Morgan, Edmund S. and Helen M. The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Powell, Lawrence N. The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.