6

The Early National Period

One of the main reasons the Anti-Federalists did not derail the Constitution was because virtually everyone expected that George Washington would become the nation’s first president. Washington was the republican ideal of a political leader: a distinguished, experienced, honest, wealthy landowner. He would rather have stayed home at his Mount Vernon plantation, but he responded to the nation’s call to lead. In his first inaugural address in April 1789, Washington spoke of the great “anxieties” he felt regarding the weight of the new office. Washington regarded his personal faith as a private matter, and he almost never spoke of Christian particulars in public. Yet in his speech he told America of his “fervent supplications to that Almighty Being who rules over the Universe, who presides in the Councils of Nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect, that his benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the People of the United States.”

Washington’s administration was a shockingly small operation compared to today’s executive branch. He had a total of two staff members and occasionally had to write his own letters. Though Washington was constantly short on money (he was “land rich but cash poor”), he sometimes bought his own furniture for the executive office. Washington set precedents with virtually every action he took, beginning with the appointment of cabinet officers to head departments created by Congress. Most critically, he named Thomas Jefferson (recently returned from Paris) as the first secretary of state, and Alexander Hamilton, his trusted assistant from the Continental Army, as the first secretary of the Treasury. Congress also created a six-member Supreme Court. Washington nominated John Jay, the prominent New York diplomat and author of several of the Federalist essays, as its first chief justice.

Figure 6.1. Federal Hall, New York, 1789. First capitol building of the United States.

Jefferson versus Hamilton

Washington came into the presidency still assuming that, as a republic, America should seek to avoid factions and political “parties.” Governing by consensus, not by the defeat of political rivals, was the ideal. But Washington found that he could not eliminate ideological divisions, even within his cabinet. The preeminent division was between Jefferson and Hamilton. The basic disagreement between them was over the direction the nation should take. Hamilton emphasized the nation’s commercial power, while Jefferson favored agriculture and liberty. (Jefferson’s ideal of liberty presupposed the unfreedom of black agricultural slaves, however.) Hamilton preferred policies that supported American business interests and America’s stature on the world stage, while Jefferson wanted to protect the interests of farmers, whom he saw as essential to the ongoing health of the economy and the republic.

Hamilton did not start out as an entrenched defender of northern mercantile interests. He was born to unmarried parents in the West Indies. His father abandoned him, and his mother died when he was a teenager. His mentors, including a Presbyterian pastor, saw great promise in Hamilton, so they sponsored him to go to King’s College (later Columbia University) in New York City. After serving with Washington during the Revolutionary War, Hamilton became a prominent New York lawyer and married into a wealthy family. Hamilton was dismayed by the economic inefficiency under the Articles of Confederation and vowed to put the nation on a stronger footing as Treasury secretary.

The old system of requisitions had never provided adequate revenues for the government under the Articles of Confederation. In 1789, Hamilton devised a national tariff (a tax on imports) that would become the chief source of federal revenues in the new government’s early years. Tariffs had been among the most controversial of the tax programs instituted by the British, and a few southern congressmen grumbled about the unequal effects of tariff policy. In effect, tariffs benefited the (mainly northern) manufacturing sector of the economy, while hurting agricultural exporters. Tariff policy would remain a contentious political issue between North and South for decades. But Hamilton was convinced that not only were tariffs the best means to raise funds for the nation’s coffers, but they would help fledgling American manufacturing businesses get off the ground. He hoped tariffs would diversify the economy beyond farming, which remained the most common occupation for Americans.

Hamilton extended his economic program by crafting a complex plan for paying down national and state debts. The problem was that his scheme also disproportionately benefited the northern over the southern states. Many of the southern states had already paid off many of their debts incurred during the Revolutionary War. The House of Representatives, led by James Madison (only recently Hamilton’s key partner in writing the Federalist essays), rejected Hamilton’s debt plan at first. But Madison, Jefferson, and Hamilton eventually struck a deal. In exchange for the Virginians’ support for Hamilton’s debt program, Hamilton agreed to support placing the new national capital in the South, on the Potomac River between Virginia and Maryland. The national capital moved temporarily from New York City to Philadelphia in 1790 and then permanently relocated to the federal city of Washington, DC, in 1800. Hamilton’s financial program remained a source of sectional conflict, but by the mid-1790s it had also helped stabilize the troubled American economy.

Hamilton was not done, however. In 1791, he added to his grandiose plans for the nation’s economy by proposing that Congress charter a Bank of the United States. The bank would make loans, regulate currency supply, and boost the business sector. Not only did this proposal generate concern about favoritism, but Madison, Jefferson, and other critics noted that the Constitution did not give Congress the authority to create a national bank. The Constitution said nothing at all about a bank, in fact. Citing the Tenth Amendment, Jefferson insisted that if the Constitution did not delegate a power to the national government, then it was reserved to the states or the people. He wrote that “to take a single step beyond the boundaries thus specially drawn around the powers of Congress, is to take possession of a boundless field of power, no longer susceptible of any definition.” Hamilton countered that the national bank fit within the Constitution’s authorization of Congress to make “all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution” its delegated power.

This was the first appearance of a long-running question in American legal history. Should we take a “loose” or a “strict” interpretation of the Constitution and the national government’s powers? Was the Constitution fundamentally meant to restrict, or to empower, the federal government? With regard to the bank, Hamilton took a loose interpretation. Later, with regard to the Louisiana Purchase, President Jefferson would show that he too could adopt a loose interpretation when it suited his political goals. In the meantime Hamilton won the day. Congress chartered the bank, and Washington signed the charter into law, even though a majority of southern congressmen voted against it. The feud bred deep, personal animosity between Jefferson and Hamilton. They traded insults, and each appealed to Washington against the other. Jefferson recalled that “Hamilton & myself were daily pitted in the cabinet” like two roosters in a cockfighting ring.

The Rise of Political Parties

The rivalry between Jefferson and Hamilton also gave rise to America’s first political parties. During ratification the Federalists and Anti-Federalists had really been disorganized movements centered around people’s views of the Constitution. They were not formal organizations fielding candidates and devising strategy. Now the “Federalists” became identified with Hamilton’s financial program and support for a closer relationship with Britain in foreign policy matters. The “Democratic-Republicans,” or just “Republicans,” led by Jefferson and Madison, opposed Hamilton and favored stronger ties with France.

The coming of the French Revolution in 1789 focused Americans’ attention on European affairs. In spite of the Revolutionary War and French alliance, many Federalists wanted to foster close ties with Britain. They had never forgotten the older American hostility toward the French. Jefferson and his supporters saw in the French Revolution (at least before it turned violent and viciously anti-Christian in 1793–1794) a kindred movement to the American Revolution. They hoped it would become the next great step for liberty around the world. As war resumed between Britain and France, President Washington issued a proclamation of neutrality in 1793. He professed a desire to maintain a friendly and impartial relationship with both France and Britain. Similar to the debate over the national bank, Madison and Hamilton engaged in a public argument in 1793 over whether the president even had the constitutional authority to declare neutrality. (Madison argued this was the role of Congress alone.) The French ambassador to America, a man called Citizen Genêt, exacerbated growing concerns over French revolutionary violence when he used obnoxious tactics to try to draw America into the European war on the French side. Jefferson’s frustration with Washington, Hamilton, and Genêt led him to resign as secretary of state by the end of 1793.

In 1794, Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay as a diplomat to London to avoid open war with the British. The British, who still maintained forts on US soil, were attacking American ships trading with the French and were “impressing” hundreds of American sailors into service in the British navy. Over howls of protest by Democratic-Republicans, Jay struck a treaty with the British. To critics such as James Madison, the treaty only won meager concessions from the British in exchange for a seeming alliance with them against the French. One Virginia newspaper called the treaty an “imp of slavery begot in hell.” Over the negative votes of southerners and Democratic-Republicans, Federalists were able to pass the treaty through the Senate with the bare two-thirds majority needed. The House was not supposed to have a role in approving treaties. But Madison and his supporters threatened to deny funding in the House for the Jay Treaty’s provisions. Some Democratic-Republicans began to discuss the possibility of impeaching Washington. That overreach helped defuse the crisis and built sympathy for the revered Washington for the two years remaining in his presidency.

Conflict with Native Americans and Frontier Settlers

Before the British withdrew from some of their forts in the Great Lakes region, they warned local Indians that the United States would take their land if they did not resist. This brought about a new round of violence in the area. In the early 1790s, American forces suffered terrible defeats in the region that would become northwest Ohio and northeast Indiana. In 1794, General Anthony Wayne led a formidable US army of 2,000 regular soldiers and nearly that many Kentucky volunteers. On August 20, 1794, Wayne’s army smashed a combined force of about 1,000 Shawnees, Delawares, Miamis, other Indians, and British Canadian militiamen who had taken up a defensive position at a line of downed trees. This “Battle of Fallen Timbers,” which happened near present-day Toledo, Ohio, ended Native American resistance in the Great Lakes region for almost two decades. Under the Treaty of Greenville (1795), Indians ceded territory to the United States in what would become Ohio. Shortly thereafter, the last British troops evacuated their Great Lakes area forts.

The US government under Washington and Hamilton determined to show strength not only against Native Americans, but against frontier settlers who resisted tax policy. As part of his broader financial program, Hamilton had gotten a tax on “distilled spirits” passed in 1791. This tax was a hardship for many corn and wheat farmers, who supplemented their incomes by distilling and selling whiskey. Not only did Americans in the 1790s have an enormous thirst for alcoholic beverages, but bottled whiskey and other alcohol was easy for farmers to take to market and sell for a good profit. (They did not have to worry about the product spoiling, as they did with fresh-grown crops.) Reminiscent of Shays’s Rebellion in the 1780s, rural western farmers in northern states reacted angrily to the whiskey tax. When they could not get it repealed, farmers in western Pennsylvania openly revolted in the 1794 “Whiskey Rebellion” and threatened to attack Pittsburgh. The framers of the Constitution had written of the need to ensure “domestic tranquility” against such threats, and Washington and Hamilton were determined to show they would not tolerate tax rebellion.

They assembled a massive force of about 13,000 men—larger than the number of Americans Washington had commanded at Yorktown in 1781—and Washington personally led them into Pennsylvania. This was not a precedent future presidents would follow: Washington was the last sitting president to go into the field as commander in chief. The massive display of might became an embarrassment when the whiskey rebels declined to make a stand and wisely dispersed. Washington and Hamilton’s army could only find a couple of dozen rebels to round up and charge with treason. Democratic-Republican critics declared that the republic was already descending into tyranny, just six years after the ratification of the more powerful Constitution. Alarmed western voters gave more support than ever before to Jefferson’s party.

An Agrarian Republic

In spite of Hamilton’s vision of a powerful, commercial America, the nation in the early republic remained overwhelmingly rural and agricultural. About 90 percent of the American population worked on the land in 1790. The vast majority lived in tiny villages or farms in the countryside. Small-time farmers often produced much of their own food and clothing. Over the course of the 1700s, men’s and women’s roles in farm work had become more differentiated. In addition to raising young children, women often labored at tasks such as making clothes and tending gardens and chickens, all with an eye toward the needs of the immediate family. Men were more likely to handle work on a farm that grew crops or pastured animals meant for regional, national, or international markets. But for most free American farming families, men and women both labored within the sphere of the farm, close to the nuclear family.

Many Americans idealized agrarian life as key to the health of the republic. Thomas Jefferson wrote in Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), the only book he ever published, that “those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people, whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue. It is the focus in which he keeps alive that sacred fire, which otherwise might escape from the face of the earth.” (Jefferson did not explain how this vision of virtuous agrarian labor justified chattel slavery and the plantation system, where black workers did the hardest labor at the bidding of white masters.) Similarly, in Letters from an American Farmer (1782), the French immigrant to America J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur wrote that free Americans were relatively equal because “we are a people of cultivators, scattered over an immense territory. . . . We are all animated with the spirit of an industry which is unfettered and unrestrained, because each person works for himself.”

Women fit into this vision of an agrarian republic because they had critical roles to fill on farmsteads. Men and women writers also idealized women as “republican mothers” who taught their children Christian virtues and the precepts of liberty. Congress defined US citizenship in ethnic terms from the beginning, offering a path to American citizenship only to “free white” people in the Naturalization Act of 1790. So white women were undoubtedly citizens, even if (like African Americans and Native Americans) they had no formal political voice. As we have seen, women had few legal rights or professional opportunities either.

In the 1780s and ’90s, some women, especially those in wealthier northern families, saw advances in educational opportunities. Many in early America approved of basic literacy for women for the purposes of Bible reading and educating children, and the “republican mother” ideal also enhanced the value of female learning. The Philadelphia physician and patriot leader Benjamin Rush took an even more expansive view, believing that if educated properly, the ladies of the nation could “not only make and administer its laws, but form its manner and character.” A number of female schools opened in northern cities during the late 1700s. The Litchfield Female Academy, founded in Connecticut by Sara Pierce in 1792, trained more than 3,000 women over the course of four decades. Pupils there studied theology, hard sciences, logic, and math, in addition to more “ornamental” topics such as the arts and embroidery.

Religion in the New Nation

For many of the nation’s citizens, the routines of church life remained essential. Following the Great Awakening, many Americans had come to expect and to pray for periodic revivals. We often think of the Great Awakening as happening only in the early 1740s, and the (less well-defined) Second Great Awakening in the early 1800s. But significant, if not nationwide, revivals were happening between the “great” awakenings. For example, New England saw a massive revival called the “New Light Stir” in the latter stages of the American Revolution. One of the main catalysts of the New Light Stir was the “Dark Day” of May 19, 1780. On that day a gloomy pall, probably caused by wildfires, covered the whole region. The darkness was so profound that some birds returned to their nests, thinking night had fallen. In a culture deeply imbued with the apocalyptic themes of the Bible, the Dark Day spawned speculation that the end was at hand.

The Dark Day brought thousands of conversions and baptisms, especially in the growing Baptist churches of New England. But it also fostered more sectarian movements outside of the mainstream Christian denominations. Some of these were led, atypically, by women. One of these movements was the Shakers, led by the messianic figure Mother Ann Lee. She began her preaching ministry in England, where she had once worked in a factory. She and her followers fled from violent persecution and went to New England and eastern New York. The Shakers got their name for the charismatic scenes at their worship services, in which (like early “Quakers”) some participants would tremble in the presence of the Lord. Lee taught that sexual relations, even within marriage, were sinful. The Shakers’ celibacy has always been a serious obstacle to their growth. But they interpreted the Dark Day as the “first opening of the gospel in America,” and they recruited a number of evangelical Christians into the Shaker fold.

The followers of Rhode Island preacher Jemima Wilkinson also saw the Dark Day as a portent of the last days. Following a near-death visionary experience in 1776, Wilkinson declared that the Holy Spirit had taken control of her body. She began calling herself the Public Universal Friend, or the “P.U.F.” for short. Declaring that the prophecies of Revelation’s woman in the wilderness had been fulfilled in her, she also suggested that God’s calling had negated her gender. Wilkinson often dressed like a male preacher and wore her hair in men’s styles. Eventually, she and her followers established a communal village in the Finger Lakes region of western New York, where she remained until she “left time” (or died) in 1819.

The Methodists also saw massive growth in the 1780s, especially in states from Pennsylvania to Virginia. English Methodist founder John Wesley had opposed the American Revolution, so many of the new Methodist preachers in America had to lie low during the war. But in 1784, Wesley authorized the creation of an independent American Methodist Church. Baltimore, Maryland, the new nation’s fastest-growing city, saw spectacular Methodist revivals in 1788–89. Baptists and Methodists both enjoyed some success in attracting African American converts, more so than had the older Congregationalist or Anglican churches. One of the Methodists’ most significant converts in America was Richard Allen. He experienced the new birth of conversion as a slave working on a Delaware farm in 1777. Methodist leaders arranged for Allen to purchase his own freedom in 1783, and Allen began serving as a Methodist evangelist. Allen and his African American colleague Absalom Jones experienced discriminatory treatment in a white-led Methodist church in Philadelphia. They decided to found independent black Methodist Episcopal churches, including Allen’s Bethel Methodist Church. In 1816, Allen would organize the African Methodist Episcopal denomination, uniting Methodist-affiliated black congregations in the Philadelphia area.

In the midst of this religious ferment, America also saw new trends in liberal theology and religious skepticism. Among evangelical Christians, traditional Calvinism and the doctrine of predestination came under severe attack from new groups such as the Freewill Baptists. Some theologians and pastors also emphasized God’s love and benevolence so much that some even endorsed the universal salvation of all people. Longtime Boston pastor Charles Chauncy, the greatest antagonist of the revivals of the 1740s, waited cautiously for decades before publishing his universalist views in the 1780s.

A number of Americans, including Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, expressed doubts about other traditional Christian doctrines, including the Trinity, the idea that the one God exists in three persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Writing to Jefferson in 1813, Adams exclaimed, “Had you and I been forty days with Moses on Mount Sinai, and . . . there told that one was three and three one, we might not have had courage to deny it, but we could not have believed it.” The most aggressive skeptic of the era was Tom Paine, the author of Common Sense. In 1794, Paine published his sensational book The Age of Reason in America, in which he attacked traditional beliefs, including the virgin birth and the resurrection of Christ. The Age of Reason became another best seller for Paine. Traditional Christians lambasted Paine. Samuel Adams wrote him and asked whether Paine thought that by his pen alone he could “unchristianize the mass of our citizens.”

The Presidency of John Adams

George Washington had endured more criticism as president than anyone expected, especially during his second term. Although the Constitution did not yet limit presidents to two terms (that would come with the Twenty-Second Amendment in 1947), Washington set a critical precedent when he decided to step down in 1796. To mark the occasion, Washington delivered his Farewell Address. James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay had all helped Washington compose the address. This made the speech arguably the “single most representative document” from the Founders, according to historian Jeffry Morrison. Washington urged Americans to avoid factionalizing into parties and to “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” He called on Americans to remember that true virtue, not political scheming, was the source of health for any republic. “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity,” Washington said, “religion and morality are indispensable supports.” Thinking of the skepticism of Tom Paine and the excesses of the French Revolution, he advised Americans to guard against those who would foolishly topple these “great pillars of human happiness.”

John Adams’s tenure as president raised more serious questions related to factions and foreign entanglements. Although they did not “run” for president in the modern sense, people understood that Adams (Washington’s vice president) was the top choice of the Federalists, and Jefferson of the Democratic-Republicans. Still using the original system of the Electoral College, Adams came in first and Jefferson second in the election. This meant that Jefferson became Adams’s vice president. Adams inherited tensions with France, whose representative in Philadelphia had advocated the election of Jefferson. Once Adams was elected, France began attacking more American ships, especially those heading for British ports. America and France both hesitated to formally declare war against each other, so this maritime conflict became known as the Quasi-War.

Adams sent a diplomatic mission to Paris to try to avoid all-out war. (France had already refused to meet with the US representative to Paris.) The French foreign minister still refused to see the delegation, which included future Supreme Court chief justice John Marshall. But anonymous agents of the French government, who became known as X, Y, and Z, met with the American envoys and demanded exorbitant bribes before negotiations could proceed. The indignant Americans returned to the United States. A popular slogan in response to this “XYZ Affair,” reportedly coined by a South Carolina representative, was “millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute.”

The furor over the Quasi-War and the XYZ Affair led the United States to the brink of widespread violence at home. Many Federalists advocated the crushing of political dissent. It was arguably the most volatile time in American politics until the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Adams and the Federalists passed a large new tax program to finance an army, which presumably would be used in the event of war with France. Adams had to send in a militia to suppress a tax revolt in eastern Pennsylvania, led mostly by German settlers. Many Federalists argued that the growing number of immigrants in the United States was destabilizing the nation and fueling the growth of the party of Jefferson.

These fears led the Federalist-controlled Congress, at Adams’s behest, to craft the Alien and Sedition Acts, the most notorious legislation of the 1790s. The Alien Acts promised to give the president expanded powers to detain and deport foreigners if war did break out. A new naturalization policy required immigrants to wait fourteen years to apply for US citizenship. This was clearly designed to delay the voting eligibility of the immigrants, who tended to prefer the Democratic-Republicans.

The most ominous of the measures, however, was the Sedition Act. This act represented the first great challenge to the First Amendment to the Constitution and its guarantees of free speech and a free press. It led Jefferson to call the 1798 furor the “reign of witches.” The Sedition Act made it a crime to “write, print, utter or publish . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States.” This was not just an idle threat. The government prosecuted twenty-five people for violating the Sedition Act, all of them Democratic-Republicans. One Vermont congressman spent four months in jail for writing about the “ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice” of the Adams administration.

The Sedition Act reminds us that the Constitution may guarantee basic rights and liberties, but maintaining or securing those freedoms often requires vigilance by the people themselves. Democratic-Republicans suggested extraordinary measures to respond to the Sedition Act, with some radicals proposing that secession (withdrawal from the Union) by the southern states might become necessary. Jefferson and Madison wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, respectively, making a strong case for the states’ ability to resist the national government. In the Kentucky Resolution, Jefferson said that the state wanted to escape the “fangs of despotism” but that it wished to avoid the dissolution of the Union. Implicitly, Jefferson was suggesting secession as a last resort. The states retained the right to review the constitutionality of laws, he maintained. When Congress adopted unconstitutional statutes, “nullification . . . is the rightful remedy,” he wrote.

The theory of nullification, which various northern and southern leaders would propound throughout American history, held that states could refuse to comply with patently unconstitutional laws. By the twentieth century, most Americans had accepted the idea that the Supreme Court was the final arbiter regarding the constitutionality of laws. (This supreme power of “judicial review” was not stated in the Constitution, but John Marshall articulated it in the foundational decision of Marbury v. Madison in 1803.) Until the Civil War, however, many Americans still believed that the states, the president, and the people had a role to play in interpreting laws and weighing them against the Constitution.

The Revolution of 1800

John Adams had better luck in negotiating with military leader Napoleon Bonaparte, who had taken over the French republic. But the damage of the Quasi-War, the Alien and Sedition Acts, and internal feuding among Federalists doomed Adams’s bid for reelection in 1800. The outcome of the Electoral College vote sent the presidential contest into chaos, however. Thomas Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, received the same number of votes and tied for first place. This threw the election into the House of Representatives, which the Federalists still controlled. Many assumed Burr would withdraw, but Burr saw a path to become president. So the House went through dozens of ballots before finally settling on Jefferson. The passage of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804 saved the nation from enduring another debacle like this one. Under its rule, Electoral College members would vote separately for president and vice president.

Whatever the disappointments of his presidency, John Adams set a critical precedent by not contesting the outcome of the 1800 election. He left office quietly. This was one of the first times in world history that an opposition party peacefully defeated its rivals in a legitimate election. It is easy to take this for granted, but among our most treasured traditions in American politics are fair elections and candidates abiding by the results of those elections. Margaret Bayard Smith, a political writer and wife of a Washington, DC, publisher, witnessed Jefferson’s inauguration and exclaimed that “the changes in administration, which in every government and in every age have most generally been epochs of confusion, villainy and bloodshed, in this our happy country take place without any species of distraction, or disorder.” Many other countries around the world do not enjoy such a tradition. Jefferson called the election the “Revolution of 1800,” believing that the tradition of the American Revolution had come under severe strain in the 1790s. He saw his election as a righting of the national trajectory.

Adams and the Federalists did make one last attempt to maintain power, however, with a court-packing scheme under the Judiciary Act of 1801. This act increased the number of federal judgeships right before Adams left office, which Adams hurriedly filled. Some justices of the peace did not have their commissions delivered by midnight on the day Adams was to leave office, and Jefferson refused to follow through on the appointments. One of Adams’s intended appointees, William Marbury, took his case to the Supreme Court, asking that they force Jefferson to appoint him. In the case of Marbury v. Madison (1803), Marshall contended that an earlier judiciary act, which had given the Supreme Court the power to issue such orders (“writs of mandamus”), was unconstitutional. Marshall cleverly denied that the court had one relatively narrow power, the writs of mandamus, in order to claim a far bigger one: the right of judicial review. From then on, the Supreme Court sought to position itself as having the last word in debates over a law’s constitutionality.

Jefferson as President

Jefferson was the first president to be inaugurated in Washington, DC, which remained an isolated village on the Potomac River. He understandably tried to call for unity in the address, while also acknowledging the reality of the party divides. “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists,” he declared. In spite of his personal skepticism about faith, Jefferson cited the nation’s “benign religion” as one of its greatest sources of unity. That faith was “professed, indeed, and practiced in various forms,” he said, “yet all of them inculcating honesty, truth, temperance, gratitude, and the love of man; acknowledging and adoring an overruling Providence, which by all its dispensations proves that it delights in the happiness of man here and his greater happiness hereafter.”

Jefferson promised to do his part to lead a “wise and frugal government.” In both style and substance, he sought to model true republican leadership. He declined to adopt the aristocratic airs of Adams and Washington (who had died in 1799). Sometimes when guests came to the presidential residence, Jefferson would answer the door himself, wearing shabby clothes and slippers. He was committed to reducing the national debt and the size of the federal government, although by today’s standards the government under Adams was still miniscule. Among other cost-saving measures, Jefferson cut the size of the army by 50 percent.

Although his efforts to downsize the government worked, they did provoke criticisms that Jefferson was leaving the nation defenseless. This charge became especially pointed in the face of ongoing attacks on American ships by the North African Barbary pirates. North African pirates had long menaced European and American ships in the Mediterranean Sea. When the United States declared independence from Britain, its ships became vulnerable targets. Washington and Adams had been reluctant to confront the pirates militarily. Paying ransoms for captured sailors and tribute for protection became the standard practice of the US government. By the beginning of Jefferson’s presidency, payoffs to the Barbary states represented one-fifth of the entire US government’s budget. Jefferson refused to keep paying tribute, precipitating war with the ruler of Tripoli. US Marines saw action in naval and land battles in the region around Tripoli in 1804–5, leading to a peace treaty in 1805. But the United States still had to pay $60,000 to free American prisoners. Problems with Barbary piracy continued until naval action under President James Madison in 1815 helped bring attacks on American ships to an end.

Some Christian critics had railed against the idea of a Jefferson presidency, citing his skepticism about traditional faith. Early in his presidency, Jefferson made clear that he would remain a champion of religious liberty. He had received enthusiastic support from Baptists because of his record on religious freedom, and Jefferson used an 1802 reply to an appreciative letter from the Danbury Baptists of Connecticut to reaffirm his view on the issue. He told the Connecticut Baptists that he was sorry their state still maintained an established church. (The First Amendment had not restricted the states’ actions with regard to establishments.) But he wrote that he contemplated “with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between church and state.” This letter has become a standard resource for jurists interpreting the First Amendment’s religion clauses. But not even Jefferson wanted to prohibit religious expression in public life. Two days after sending the “wall of separation” letter, Jefferson hosted Baptist pastor John Leland, a longtime ally of Jefferson’s on religious liberty, for a sermon before Congress.

Jefferson and the West

Jefferson’s vision of an agrarian republic meant he wanted to secure more land for white settlers in the West, including the Mississippi River Valley. But France had acquired the vast Louisiana Territory from Spain in 1800. This area covered roughly the middle third of the continent, from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west. It also included the key port city of New Orleans. Napoleon Bonaparte originally hoped to use New Orleans as a base to expand the power of the French empire in the Americas. But Bonaparte’s plans floundered because of the success of the slave rebellion on Saint-Domingue, or Haiti, which Toussaint L’Ouverture had started in 1791. Bonaparte’s army, sent to crush the rebellion, lost tens of thousands of men by the end of 1802.

When American diplomats approached the French about securing the rights to New Orleans, they discovered that Bonaparte had grown weary of trying to control France’s holdings in North America and the Caribbean. The French foreign minister proposed selling the entire Louisiana Territory to the United States for $15 million, an enormous sum at the time. But given what it bought the United States, the Louisiana Purchase must be considered one of the greatest bargains in national history. Although Jefferson worried about whether acquiring territory this way was strictly constitutional, the Senate did not quibble much about it and approved the treaty in 1803. This was the most important event of Jefferson’s presidency, as it dramatically reshaped the nation’s size. The purchase also set the stage for festering conflict over the status of slavery in the Louisiana Territory and other areas in the West. One critical newspaper wondered whether Jefferson and the Republicans, “who glory in their sacred regard to the rights of human nature,” were purchasing “an immense wilderness for the purpose of cultivating it with the labor of slaves.” The residents of the territory, primarily Indians, were not consulted about the sale.

Like many Americans, Jefferson remained fascinated with the prospect of finding a transcontinental water route to the Pacific. In the midst of the negotiations over Louisiana, Jefferson tasked two Virginians, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, to explore the Missouri River into the northwestern interior. They set out from St. Louis in May 1804, accompanied by forty men, including a slave of Clark’s, whose name was York. When they met new groups of Indians, the expedition would explain to them that they should give allegiance to Jefferson, the “great Chief the President.” They gave many gifts to Indians, including American flags and medals with Jefferson’s image on them. By October 1804, the expedition had reached a large conglomeration of Mandan Indian villages in present-day North Dakota, where they wintered.

In the spring of 1805, the expedition secured the assistance of a Shoshone woman named Sacagawea, along with her French Canadian husband and their infant child. Sacagawea’s scouting and translating services were essential to the journey’s success. The passage across the Rockies and the Continental Divide posed enormous challenges, and at times the party was reduced to drinking melted snow and eating their own horses. They finally reached the Pacific Ocean (or the Columbia River estuary) in November 1805. By the time they returned to St. Louis in 1806, they had discovered and described hundreds of new species of plants and animals and laid American claim to the Pacific Northwest.

Figure 6.2. Map of Louisiana Purchase. A map of the historical territorial expansion of the United States, with future states listed.

Jefferson, Aaron Burr, and Political Intrigue

In light of the successes of Jefferson’s first term, he easily won reelection in 1804. But below the surface, political intrigues were swirling. Aaron Burr, a grandson of Great Awakening theologian Jonathan Edwards and Jefferson’s vice president, ran (unsuccessfully) as an independent candidate for governor of New York in 1804. Some Federalists supported Burr, but New York’s Alexander Hamilton opposed him, calling him dangerous and untrustworthy. Their feud escalated when Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel, a ritual that was often a stylized clash that led to no injuries. Historians have hotly debated the men’s real intentions at the duel. What we know for certain is that Hamilton shot at but missed Burr, and Burr then shot Hamilton, who suffered severe internal injuries. As he lay on his deathbed, Hamilton asked for an Episcopal bishop to visit him, requesting that the bishop serve him Communion. The bishop balked because Hamilton had never joined the church and because dueling was considered sinful. But Hamilton persisted and promised never to participate in a duel again if he survived. The bishop asked him if he would repent of his sins and put his faith in Christ, and Hamilton said that he did. He also said that he forgave Burr, after which the bishop gave him Communion. The next day, Hamilton died.

Burr fled to the South to avoid murder charges, but his political schemes were not finished. Still smarting over his political losses and the embarrassment of the Hamilton duel, Burr hatched a plot to get the southern part of the Louisiana Purchase, including New Orleans, to break away from the Union and to become an independent nation with Burr as its leader. But the confusing plan did not get off the ground before one of Burr’s conspirators notified the Jefferson administration, which ordered Burr’s arrest. Although Jefferson had once toyed with the idea of secession in the Kentucky Resolution, now he had Burr charged with treason, in a case heard by Supreme Court chief justice John Marshall. Because Marshall insisted on a high standard for the definition of treason, Burr was acquitted. But Burr’s once-promising career was ruined.

Jefferson also faced more conventional challenges from other members of the Republican Party, politicians known as the Old Republicans or “Tertium Quids.” They criticized Jefferson and Madison for betraying the old Jeffersonian principles of agrarianism and limited government once they got a taste of political power. The most colorful character among the Old Republicans was John Randolph of Roanoke (Virginia), who proclaimed that real Republicans stood for “love of peace, hatred of offensive war, jealousy of the state governments toward the general government; a dread of standing armies; a loathing of public debts, taxes, and excises; [and] tenderness for the liberty of the citizen.” Although Randolph is not well-known today, conservative political philosopher Russell Kirk called him “the most singular great man in American history.” Known to contemporaries as a “flowing gargoyle of vituperation,” Randolph developed a reputation as the most vicious purveyor of insults in Congress. Randolph displayed an exaggerated fashion of the southern gentleman in the English style, wearing long coats over white boots and spurs into Congress’s chambers, accompanied by a hunting dog, which slumbered under his desk as he gave his florid speeches. Randolph opposed most initiatives of the Jefferson and Madison (elected in 1808) administrations. His reputation for combativeness lasted for decades. He and Speaker of the House Henry Clay engaged in a duel in 1826. It turned out better than the Hamilton-Burr duel, as both participants fired and missed.

Embargo

Troubles with European powers that dated back to America’s victory in the revolution were the greatest source of strife in Jefferson’s second term as president. France and Britain both preyed on American ships, capped by the 1807 British attack on the American vessel Chesapeake outside of Norfolk, Virginia. When the British refused to apologize or compensate for the Chesapeake, Jefferson decided on a drastic course of action: he banned American ships from entering foreign ports. The Embargo Act (1807) overestimated both Europe’s dependence on American goods and Americans’ willingness to support this extraordinary move. The embargo threw the American economy into depression, with income from American exports dropping from $108 million to $22 million in one year. A few merchant shippers made fortunes off of a new smuggling trade, however. Doubling down on the embargo, Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans passed increasingly harsh enforcement measures that seemed to ignore the Constitution’s prohibitions against unlawful searches and seizures and its guarantee of due process of law. John Randolph declared the embargo the “most fatal measure that ever happened in this country,” and scoffed that the policy was like attempting to “cure corns by cutting off the toes.”

Congress finally acknowledged that the embargo had been a total failure, repealing it the day Jefferson’s presidency ended in 1809. As promising as Jefferson’s first term had been, his decision for the embargo and the accompanying intrusions into the economy had ruined his second term. Jefferson was delighted that his time in Washington was over. The Federalists (still strongest in the northern states) as well as Old Republicans like Randolph were delighted to see Jefferson go. Randolph proclaimed that no other administration, not even John Adams’s, had “left the country in a state so deplorable and calamitous.” Randolph and many Old Republicans supported Virginia’s James Monroe to succeed Jefferson. But Jefferson’s wing of the Democratic-Republican Party maintained enough power to elect James Madison as president in 1808, and the Democratic-Republicans also kept control of Congress.

James Madison and the War of 1812

Madison inherited problems of trade and diplomacy from Jefferson. To replace the embargo, Congress passed a new act allowing trade with all European nations except for Britain and France. The United States reached a tentative agreement with France to stop seizures of American ships in 1810 but failed to do so with Britain. Madison exhorted Congress to declare war with Britain. (Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution had vested the power to declare war in Congress.) Madison argued that Britain had never shown America respect as an independent nation and that a war would finally show that Americans were no longer colonists. In 1812, Congress narrowly voted to declare war, depending exclusively on Democratic-Republican votes. The Federalists dismissed the conflict as “Mr. Madison’s War.” Disgruntled Republicans allied with Federalists to try to defeat Madison in the November 1812 election. Madison won reelection in a close national vote, however, taking the Electoral College by 128 to 89 votes over New York’s DeWitt Clinton.

Besides trade disputes, a major contributing factor to the War of 1812 was continuing violence between British-backed Indians and US forces on the trans-Appalachian frontier. Going back to the colonial era, Native Americans had struggled to present united resistance against white people’s incursions on their territory. In the early 1800s, however, the Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa led the most important pan-Indian movement of the early national period. Tecumseh was the more diplomatically minded of the two, traveling among both northern and southern Indian groups and calling them to stand against the power of the American nation.

Tenskwatawa was a native prophet and spiritual leader, calling on Indians to return to their traditional ways of life and to reject dependence on whites. “White men have corrupted us, and made us weak and needful,” Tenskwatawa proclaimed. “Our men forgot how to hunt without noisy guns. Our women don’t want to make fire without steel, or cook without iron. . . . Some look in those mirrors all the time, and no longer teach their daughters to make leather or render bear oil. We learned to need the white men’s goods, and so now a people who never had to beg for anything must beg for everything!” American forces led by Indiana territory governor William Henry Harrison struck a terrible blow against the brothers’ movement when Harrison destroyed Tenskwatawa’s village of Prophetstown, Indiana, in the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. The encounter earned Harrison the nickname “Tippecanoe,” a moniker that would play an important role in Harrison’s successful campaign for president in 1840.

The primary problem with the War of 1812 is that the United States, at the outset, was in no position to fight a war against Britain. In spite of the embargo, Jefferson and Madison had largely stuck to the policy of low taxes and small government, including a small peacetime military. Britain still had a powerful army and navy, and the British would enjoy the support of Tecumseh’s alliance of Indians. Still, the war’s backers imagined that it might enable the United States to expel the British from Canada and the Spanish from Florida.

American efforts to invade Canada in the first two years of the war led to a string of embarrassing defeats. Some good news finally came in 1813 with the American naval defeat of the British on Lake Erie, near the Ohio coast. William Henry Harrison followed up with a major victory over the British and Tecumseh’s Indian forces in Ontario, Canada, at the 1813 Battle of the Thames. Tecumseh perished during the battle. The war in Canada ground to a stalemate from this point forward.

In the South, US forces clashed with a pro-British faction of the Creek Indians called the “Red Sticks.” In 1813, the Red Sticks overran Fort Mims in south Alabama, taking scalps and massacring hundreds of white settlers and pro-American Creeks, including women and children. The atrocities at Fort Mims provoked US forces led by Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, whose soldiers called him “Old Hickory,” to hunt down the Red Sticks. In March 1814, Jackson’s army, aided by Creek and Cherokee supporters, surrounded a Red Stick camp on the Tallapoosa River in central Alabama. In the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson’s forces crushed the Red Sticks and shot many as they tried to flee across the river. Some 800 or 900 of the 1,000 Red Sticks at the battle died, rendering the Red Sticks unable to fight against US forces any longer. In the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson, the Creeks had to give up more than 20 million acres of land in south Georgia and much of Alabama.

Aside from the Gulf Coast and the US-Canada border, the third major theater of the War of 1812 was the mid-Atlantic coast. The British navy controlled much of the Chesapeake Bay region, assisted in part by runaway slaves. As they had during the American Revolution, some British commanders promised to grant slaves freedom if they left their masters and fought on the British side of the war. More than 3,000 slaves from Virginia and Maryland took them up on this offer.

In 1814, the British seized upon American vulnerability on the mid-Atlantic coast to invade Maryland and to destroy Washington, DC. Although the capital remained small during the Madison administration, it was still humiliating for the British to enter the city largely unchallenged in August. James and Dolley Madison escaped the White House just before the British troops arrived. The Madisons managed to save a portrait of George Washington and a copy of the Declaration of Independence, but the British burned the White House, the Capitol, and other government buildings.

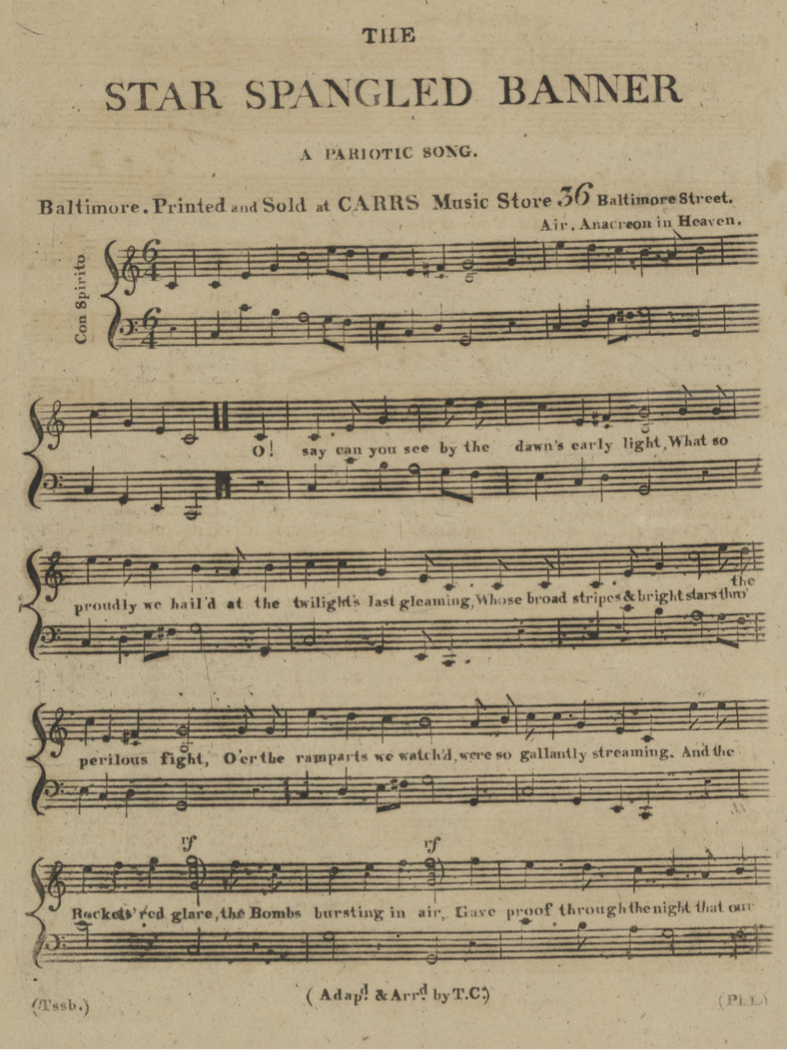

The British then turned north, descending on the burgeoning city of Baltimore, Maryland. In September 1814, they bombarded Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor, but the American defenders would not crack. Baltimore was saved. A Baltimore lawyer named Francis Scott Key had watched the bombardment and was moved to write a poem, “The Star-Spangled Banner” (or “Defense of Fort McHenry”), when he saw the American flag still flying over the fort at daylight. In 1931, Congress made the poem, which had been set to the tune of a popular English song, America’s national anthem.

The British failure at Baltimore as well as defeats in New York and Florida convinced the British to begin peace negotiations. In December 1814, American and British diplomats meeting in Belgium agreed on the Treaty of Ghent, which effectively endorsed the boundaries that existed before the war. The British promised to respect US territorial claims and to stop fostering Native American resistance in the Great Lakes region. The War of 1812 was basically a draw between Britain and the United States, but it ended the now-deceased Tecumseh’s pan-Indian alliance against American power.

The fighting in the war was not finished, however. Arguably its most important battle, the Battle of New Orleans, happened after the diplomats had signed the peace treaty because news of the peace had not yet arrived in America. In late 1814, Britain had begun planning an attack on the key Gulf Coast city of New Orleans. General Andrew Jackson devised an elaborate system of defenses to protect the city. The British attacked in January 1815, surging against Jackson’s motley army of US Marines, regular army soldiers, militiamen (who included hundreds of free African Americans from Louisiana), dozens of Choctaw Indians, and a group of pirates led by Captain Jean Lafitte. Jackson’s fighters and staunch barricades proved immovable. They dealt the British their worst defeat of the war, with thousands of British casualties, compared to only a few dozen American losses. The Battle of New Orleans did not influence the peace negotiations. It was, however, a critical psychological victory and a splendid conclusion to the war for Americans. New Orleans cemented Jackson’s reputation as a national hero, boding well for his political future.

Hartford Convention

The Federalists never supported the War of 1812, and their anger spilled over in late 1814 with the meeting of the Hartford Convention in Connecticut. There delegates from the New England states (where the Federalists were strongest) met to discuss measures to counteract “Mr. Madison’s War.” They also wanted to stop such a divisive war from ever happening again. The convention proposed a series of constitutional amendments that would limit southern power and curtail the president’s ability to start a war in the absence of broad national consensus. Among the amendments they proposed were the abolition of the three-fifths clause, which gave the South disproportionate political power by counting every slave as three-fifths of a person for representation in Congress and the Electoral College. (As at the Constitutional Convention, northerners generally opposed counting slaves at all for representation.) They also sought to require a two-thirds supermajority in Congress for declarations of war and to prevent successive presidents coming from the same state. This last measure targeted the power of Virginia, which would have one of its citizens as president (Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, each of whom served two terms) for thirty-one of the first thirty-five years under the Constitution.

Figure 6.3. Page of music to “The Star Spangled Banner,” 1814. Music by John Stafford Smith. Lyrics by Francis Scott Key.

Some radical Federalists spoke of trying to remove James Madison from the presidency. Some even proposed that the New England states could secede from the Union if Democratic-Republicans did not satisfy their concerns. Secession was not a new idea. After all, when America declared independence in 1776, that was a form of secession from the British Empire. During the ratification debates in 1787–88, some Anti-Federalists suggested secession from the Union if the Constitution was adopted. Thomas Jefferson had hinted at secession in the Kentucky Resolution of 1798. The New England radicals were proposing something that was not an unheard-of alternative. In any case, moderate Federalists limited their proposals to just the amendments, which they sent off to Washington.

Figure 6.4. Statue of Andrew Jackson in Jackson Square in New Orleans. Sculpture by Clark Mills.

The Federalists’ timing was exquisitely bad. Their demands arrived in Washington right around the same time as the news of the Treaty of Ghent and of Jackson’s spectacular victory at New Orleans. Madison and the Democratic-Republicans ignored the Federalists’ requests, which now seemed unpatriotic. Because of the Hartford Convention, the Federalist Party was fatally associated with disloyalty and disunion. By the 1816 election, the Federalists did not even field a formal nominee for president. Soon the party of George Washington, the “father of his country,” had ceased to exist. The War of 1812 helped accelerate changes that turned America into a much larger, and more democratic, nation than the one Washington had known.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cott, Nancy F. The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1780–1835. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

Dreisbach, Daniel L. Thomas Jefferson and the Wall of Separation between Church and State. New York: NYU Press, 2002.

Freeman, Joanne B. Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

Kukla, Jon. A Wilderness So Immense: The Louisiana Purchase and the Destiny of America. New York: Knopf, 2003.

McCoy, Drew R. The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980.

Sharp, James Roger. American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993.

Slaughter, Thomas P. Exploring Lewis and Clark: Reflections on Men and Wilderness. New York: Knopf, 2003.

———. The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Stagg, J. C. A. The War of 1812: Conflict for a Continent. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.