10

Learning and Belief in Antebellum America

In the early republic, Americans’ connections between learning, religion, and virtue remained inseparable. Intellectual life was dominated by debates over theology and how faith related to society, science, and reform. Even westward migration had religious and educational significance. As we have seen, when Congress organized the Northwest Territory in 1787, they called for systems of education as settlement moved west. America needed education to keep up with westward immigration because “religion, morality and knowledge [was] necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind.”

Three decades later the Connecticut legislature spoke for many when it exhorted those moving west to “plant the foundations of literature and religion” as they went. They enjoined the immigrants to think about a time, a century or two in the future, when they might be able to look down from heaven upon their American descendants living everywhere “from the Alleghenies to the sources of the Missouri; from the banks of the Hudson to the shores of the Pacific:—to behold them everywhere enlightened and pious and happy, under the mild reign of the PRINCE of peace.” They might even participate in establishing the millennial kingdom of Christ, a “bright summer which will not set for a thousand years!” Underneath that kind of spiritual confidence in America, however, there were divisive currents about issues such as the fate of traditional theology and the connection between the Bible and chattel slavery.

Dating to the colonial era, New England led the way in education. The Puritans had established schools to encourage basic literacy for both boys and girls. Theirs was a religion of literacy. All believers needed to be able to read the Bible for themselves. The Puritans and their descendants set the pace in college education (originally for men only), with the creation of Harvard College in 1636, and Yale College in 1701. A desire for nonsectarian higher education appeared in the eighteenth century such as when Benjamin Franklin helped to found the University of Pennsylvania in 1755. But more commonly, new schools grew out of the ferment of the Great Awakening, including Princeton (1746), Brown (1764), and Dartmouth College (1769). The evangelical founder of Dartmouth originally designed it as a charity school for Christian Native Americans, but that vision for Indian education faded once the school relocated from Connecticut to New Hampshire in 1770.

In the early republic states often proved slow to fulfill the kind of vision of spiritual education cast by the Connecticut legislature. In most cases churches and denominations continued to fill the need for “public” education. The Sunday school movement of the early 1800s sought to provide literacy and Bible knowledge to hundreds of thousands of children. Typically these schools met on the Christian Sabbath, with the assumption that this traditional day of rest was the best day to reach children with religious education. The Sunday schools were run by denominations or nonsectarian Protestant organizations such as the American Sunday School Union. Individual churches only adopted Sunday school programs later.

African Americans’ and Native Americans’ educational options were more limited than whites’, and they came almost exclusively through churches or religious charities. Missionary societies such as the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions set up schools among tribes, including the Cherokees. But those missionary schools ran afoul of the Indian removal crusade under Andrew Jackson’s administration. Sunday schools made some (controversial) efforts to reach out to black children and adults, especially in the North. In an age when education for girls was still limited, formal learning opportunities for African American girls were perhaps the rarest of all. Nevertheless, encouraged by abolitionists, an educator named Prudence Crandall opened a short-lived and much-maligned school for African American girls in Connecticut in 1833. The Connecticut legislature passed a law requiring a town’s assent before anyone could run a school for out-of-state blacks. Crandall was forced to close the school in 1834.

“Secular” American Education

At every level, close connections between religion and schools persisted in early national America. Such connections were hardly prohibited by the establishment clause of the First Amendment. That clause (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion”) only prevented the Congress from establishing a national denomination. Until the mid-twentieth century, American law interpreted the First Amendment as giving latitude to the states to maintain connections with religion or even to maintain an established state denomination. Several of the New England states continued to give preferential treatment to the Congregationalist Church into the early 1800s. Government support for “religious” schools was unexceptional in the antebellum period.

Nevertheless, some Americans wanted to create separation between government and denominational schooling. An important milestone in this secularizing story was the Supreme Court case of Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819). A fracas over the administration of the college had prompted the New Hampshire legislature to get involved and to defend Dartmouth’s embattled president. This intervention raised the question of whether Dartmouth was fundamentally a church-run private institution or an agency of the state of New Hampshire. Before 1819, it had features of both a public and a private college. Daniel Webster, a graduate of Dartmouth, argued before the Supreme Court that the state legislature had no right to tamper with the college’s internal governance. The Court agreed, protecting Dartmouth from public interference. This secured Dartmouth’s legal standing as a private religious college, but it also suggested that public schools could not also be church affiliated.

Thomas Jefferson also dreamed of founding the University of Virginia (1819) as a nonsectarian school, although it would be a stretch to call the university “secular” at its inception. On one hand Jefferson did not want the university to employ any professors of divinity or theology. But he acknowledged that the school would offer study of the biblical languages and Latin as well as ethical instruction in moral precepts “on which all sects agree.” He envisioned each major denomination building a divinity school at the university. Under that system individual denominations could avail themselves of the university’s services without Virginia having to promote the theology of any one church. Jefferson had hoped to employ his friend Thomas Cooper as one of the first professors at the University of Virginia, but traditional Christian critics protested that Cooper seemed to be a Unitarian (one who did not believe in the Christian doctrine of the Trinity). Cooper instead became the president of another public southern school, the University of South Carolina, which had been founded in 1801. He served for more than a decade there. In 1833, Cooper also had to step down at South Carolina partly due to controversy over his unorthodox beliefs.

In spite of examples such as Virginia’s and South Carolina’s public universities, denominations were the sponsors behind most academy and college openings in the antebellum era. In 1815, there were 33 colleges and universities in the United States. By 1848, there were 113. Protestant denominations led the way, but Catholics also founded their own institutions. The Catholic ( Jesuit) Georgetown University was founded in 1789 and accepted its first class in Washington, DC, just months after the founding of the federal city on the Potomac. As settlement proceeded west, denominations tried to keep pace with churches and colleges. To cite just a few examples, Congregationalists founded Oberlin College in Ohio (with the revivalist Charles Finney serving as one of its first professors) in 1833, Catholics started Notre Dame in Indiana in 1842, and Baptists established Baylor University in 1845, chartered by the Republic of Texas.

A distinctive feature of antebellum education was the study of “moral philosophy,” based on the “common sense” strain of thought coming out of eighteenth-century Scotland. This intellectual system assumed there was unity between the truths revealed in Scripture and those understood by human reason. Moral truths were objective. All honest, educated people could know those truths, even if they had not experienced salvation through Christ. Some traditional Christians hesitated to embrace “common sense” wholesale. They wondered whether people could truly know all of God’s truth outside of a conversion experience and saving faith. But most educators believed moral philosophy was as subject to scientific investigation as any discipline.

Though most instructors of moral philosophy affirmed traditional Christian beliefs, many downplayed the need for a dramatic conversion experience. Moral philosophers also tended not to emphasize issues on which Protestants disagreed such as the interpretation of the Lord’s Supper or baptism. They gravitated toward those truths to which most Protestants assented. Perhaps the most influential writer in the antebellum collegiate curriculum was Brown University president Francis Wayland, a Baptist minister whose Elements of Moral Science textbook (1835) was used widely across the North and South. Even though Wayland conceded that we need the Holy Spirit to illuminate God’s truth, he presented reason and biblical revelation as two paths that led to the same harmonious truth. Wayland taught many future politicians and educators, including James Angell, who would serve from 1871 to 1909 as the president of the University of Michigan (founded in 1817).

As we have seen, some female academies had begun to appear in northern towns during the late 1700s. A handful of religious colleges made college education available to women in the antebellum era. Oberlin College began admitting women several years after its founding, making it the oldest coeducational college in the United States. Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (later College) opened in Massachusetts in 1837, the same year Oberlin admitted its first women. Mount Holyoke is the oldest educational institution originally chartered as a college for women in America. Mount Holyoke’s founder, Mary Lyon, was committed to the “New Divinity” strand of evangelical Calvinist theology. This was the theology that animated much of the Second Great Awakening in New England. Thus, Lyon’s educational philosophy was more rooted in the need for conversion, and the mandate to evangelize, than was the perspective of many male colleges at the time. Although voting rights for women were slow to materialize, educational opportunities for women (at least white women) steadily improved. By 1880, one-third of all college students in America were female.

The “Common School”

Most Americans in the nineteenth century, even most white men, did not go to college. Of broader popular significance were trends in educating children. Before the antebellum era, outside of New England, childhood education outside the home was spotty and non-compulsory. Whig education reformer Horace Mann became the champion of the “common school” movement in the 1830s. Beginning with his own state of Massachusetts, Mann envisioned creating state-supported schools that all used the same curriculum and textbooks and that employed teachers trained at state-run schools. He especially wanted to employ women as teachers because they represented a ready labor force. People were used to the idea of women training children, in any case. Women teachers were paid lower wages than men, so they also appealed to politicians needing to fund the common schools. Thanks in part to Mann’s ideas, teaching became the first common profession outside the home for American women.

As in the nonsectarian colleges, the common schools would teach ethics and morality based on common assumptions of Protestant Christians. Otherwise the schools de-emphasized theology and prioritized the virtues of democratic citizenship and American patriotism. Some critics saw Mann’s common schools as elitist social programming and wanted to give individual towns more latitude to educate children as they saw fit. But the rampant population growth and tide of immigration from Europe gradually overwhelmed these complaints. Mann and his disciples warned that if Americans did not receive a common education, America’s republican culture was at risk.

The common school advocates worried about the influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany in the antebellum era and wanted to inculcate more properly Protestant values in those families’ children. Understandably, Catholic families were hesitant to cooperate with what seemed like a reeducation program that sought to steer their children away from Catholicism. Especially in large northern cities, Catholics built an elaborate network of parochial schools to avoid the common schools’ generic brand of Protestantism. State legislatures in the nineteenth century began steering funding away from sectarian schools of any kind. Legislators worried that Catholics might make a convincing case that their schools should receive state funding if Protestant schools also received public funds. Defenders of the common schools insisted that they did not promote any particular denomination, even though they typically had readings from the King James Bible and other religiously themed works. Whatever the religious implications of the common school movement, it undoubtedly reduced illiteracy in America. In 1840, illiteracy stood at less than 10 percent of white adults.

Faith and Science

Whether they chose to emphasize theology or reason, conversion or virtue, most American educators before the Civil War assumed there was a comfortable relationship between science and religion. Following the model of great scientists such as England’s Isaac Newton, they believed scientific knowledge revealed God’s glory in creation. One of the era’s most popular science textbooks was Englishman William Paley’s Natural Theology (originally published 1805). It popularized the concept that the natural world had innumerable evidences of divine design. As of the American Revolution, there were effectively no atheists in America, if by “atheism” we mean people who literally believed there was no God. Even deists would affirm the existence of the “Creator” God of the Declaration of Independence, who was the author of nature’s laws. How involved that God was in everyday life or how Jesus of Nazareth related to that God were different questions.

Christian academics and theologians disagreed about specific issues such as the age of the earth. Some affirmed the “days” of Genesis 1 as literal twenty-four-hour periods; others saw these days as representing long ages. Likewise, some scientists affirmed that God had created humans and animals in their current form at creation, while others argued that different species developed over long periods of time (though still by God’s plan). Even when Charles Darwin published his landmark On the Origin of Species (1859), scientists’ and theologians’ reactions to Darwin’s theory of evolution ranged across a wide spectrum. Harvard professor Louis Agassiz rejected Darwin’s model of natural selection and evolution in favor of the special creation of the species by God. Another Harvard professor, botanist Asa Gray, became one of Darwin’s chief promoters in America, in spite of Gray’s traditional Christian beliefs. Gray argued that evolution was merely God’s way of bringing humans and the various animal and plant species into being.

Many Christian theologians also accepted Darwin’s theory of evolution as just one more facet of God’s plan in creation. Others, however, saw Darwin as opening the door to a purely naturalistic, even atheistic, view of the natural world. Charles Hodge of Princeton Seminary warned traditional Christians not to accept Darwinism’s dangerous implications. “The great question which divides theists from atheists—Christians from unbelievers—is this,” Hodge declared: “Is development an intellectual process guided by God, or is it a blind process of unintelligible, unconscious force, which knows no end and adopts no means? In other words, is God the author of all we see, the creator of all the beauty and grandeur of this world, or is unintelligible force, gravity, electricity, and such like?” Other Christians, including Harvard’s Asa Gray, saw no necessary contradiction between God’s intelligent design of the species and evolution. Hodge was not so sure. The Princeton theologian developed his anti-Darwinist argument in his 1874 book, What Is Darwinism?

The Bible and Slavery

Americans before the Civil War were aware that some skeptical elites questioned the authority of the Bible. Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason had done so publicly. Even though Thomas Jefferson kept his skepticism private most of the time, his private correspondence revealed an admiration for Jesus’s moral teachings along with a deep distrust of the Christian tradition, including Scripture. Even Jesus’s own doctrines “were defective as a whole,” Jefferson wrote in 1803, “and fragments only of what he did deliver have come to us mutilated, misstated, & often unintelligible” in the New Testament and Gospels. Three decades later some Americans read the German writer David Strauss’s Life of Jesus (Das Leben Jesu) (1835), which denied Jesus’s divinity and miracles and had therefore scandalized traditional Christians in Europe. But most Americans, aside from a few intellectuals influenced by the emerging movement of “higher criticism,” believed the Bible was completely true and authoritative. It was the book that most white and black Americans were likely to know well, even if they had little formal education.

Figure 10.1. Charles Hodge. Engraving by Henry Howe, 1880.

In the antebellum era, however, it was becoming evident that American Christians could not agree on what the Bible taught about slavery. The Bible neither denounced nor overtly endorsed slavery. It seemed to assume its existence in forms common to the ancient world. The Bible’s lack of a clear stance on the issue enabled advocates for and against slavery to use Scripture for their arguments. British and American Christians had been engaging in these disputes since at least the late seventeenth century. Once the national debate over slavery’s future became heated during the Missouri Compromise, however, more Christians on both sides of the debate weighed in with increasing volume and vitriol. Because so many had come to accept the precepts of “common sense” philosophy, they could not account for Christians’ disagreeing on such a fundamental social issue. Shouldn’t the Bible’s teaching be clear on such a matter? By the 1830s, debaters often accused their opponents of dishonesty and corruption in their methods of biblical interpretation.

One of the last reasonably restrained American debates over slavery came in 1846, when Brown University’s Francis Wayland, and Richard Fuller, one of the founders of the new Southern Baptist Convention, published Domestic Slavery Considered as a Scriptural Institution. Fuller acknowledged that many slave owners committed sins of cruelty, but that did not make slavery immoral at its core. “The Bible did authorize some sort of slavery,” Fuller wrote, so there was no possibility that slavery per se was sinful. If slavery were sinful in every form, then the Bible was endorsing sin. Wayland countered that slavery was immoral because it denied the basic equality of slaves, who were all created in God’s image. Wayland was a relative moderate on slavery, however, as he stopped short of accusing all slave owners of committing sin simply by owning slaves. More radical critics of slavery such as Theodore Dwight Weld did not hold back. Weld was a convert of revivalist Charles Finney, who married the antislavery and women’s rights activist Angelina Grimké. In The Bible against Slavery (1837), Weld argued that slavery was always wrong because it violated the Bible’s commands to love one’s neighbor. Weld also argued that the Old Testament’s many “bondsmen” actually were paid servants, which would mitigate against the Bible’s seeming acceptance of slavery.

These debates inevitably raised tensions within the major national denominations. Could slaveholding Christians also remain in good standing within the churches? Most white southerners said yes, but growing numbers of northern Christians said no. In 1844, the Methodist Church split when officials voted to suspend a bishop who had married a woman who owned slaves. That action led to the creation of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Given that the Methodist Church was the nation’s largest Protestant denomination, this was an ominous development.

While English Methodist founder John Wesley had denounced slavery in 1774, Baptists in America had a more ambivalent history on the issue. Some early Baptists in the South expressed revulsion against slavery, and early Baptist churches gave authority to African American members as exhorters and elders. But as with white Methodists in the South, the antislavery white Baptist impulse faded as the Cotton Kingdom grew in the early nineteenth century. Many African American Baptists continued to believe slavery was wrong, of course, but growing numbers of southern white Baptists such as Richard Fuller emphasized that Christians could own slaves without committing sin in doing so. In the 1830s, certain Baptist churches and associations in the North came under abolitionist influence and declared that they would maintain no fellowship with slaveholders. Since slavery was either banned or was on a path toward gradual elimination in most of the northern states, these abolitionist Baptists were really targeting the proslavery white Baptists of the South.

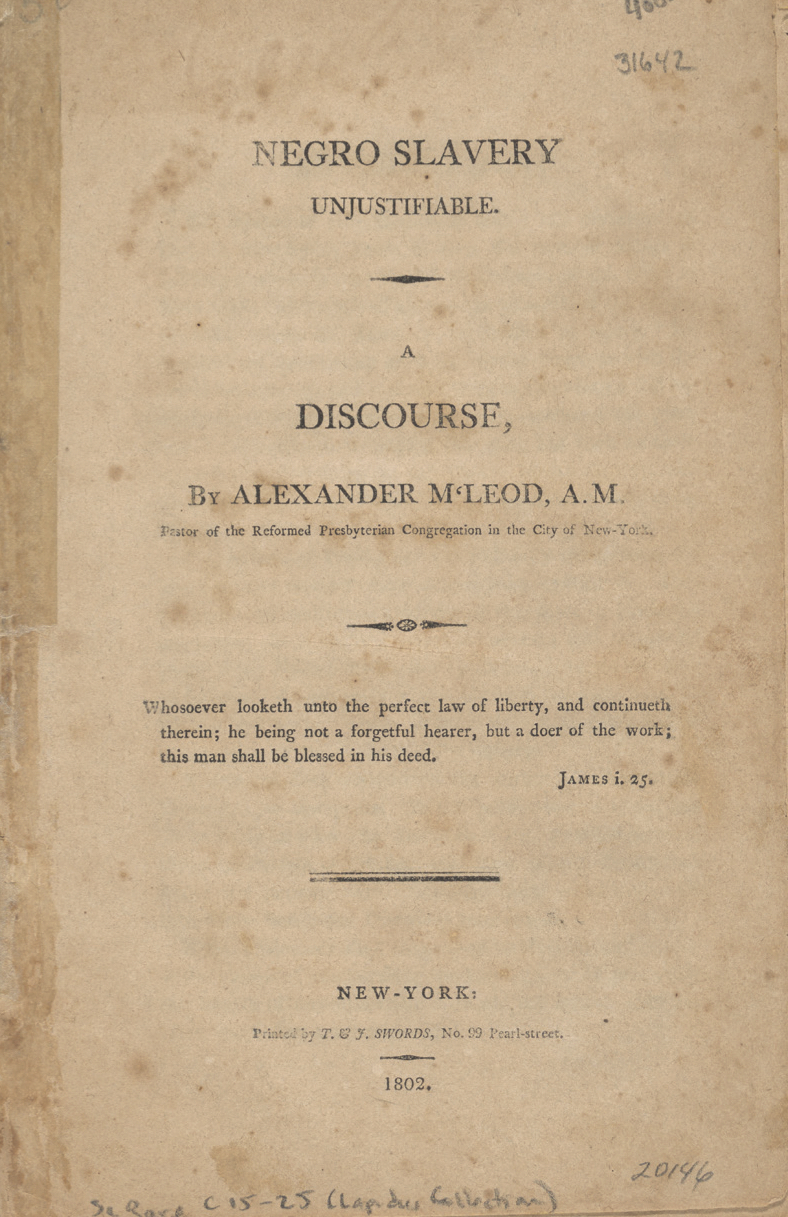

Figure 10.2. Title page to Negro Slavery Unjustifiable: A Discourse by Alexander McLeod, 1802.

In 1840, a radical antislavery Baptist pastor from New York became the head of the national Baptist foreign missions board. He proclaimed that Baptists in good standing should not fellowship with slaveholders. Other officials in the Triennial Convention, the organizational framework of the national Baptist denomination, tried to maintain harmony between pro- and antislavery Baptists. Baptists in the South argued that the antislavery activists were injecting partisan politics into what should be spiritually focused denominational agencies.

Baptist tension over slavery came to a head in 1844, when southern delegates sought to ascertain whether slaveholders could be appointed as domestic or foreign missionaries. When those missions agencies signaled they would no longer appoint slaveholders to such posts, white Baptist leaders in the South declared that the Triennial Convention and its agencies had taken sides against the proslavery brethren. An assembly of about 300 white Baptists met in May 1845 and announced the formation of the Southern Baptist Convention. They professed they were not creating this new convention to defend slavery but to stop the pointless controversies precipitated by abolitionist zealots. But they also believed owning slaves should not prohibit anyone from serving in a missionary or ministerial position in Southern Baptist churches or agencies. The Southern Baptist Convention eventually became the largest Protestant denomination in America. In 1995, the denomination would formally repent for the “role that slavery played” in the denomination’s beginnings.

If appeals to the text of the Bible did not resolve the debate over slavery, appeals to Christian sentiment certainly helped solidify northern opinion against slavery. Christian sentiment against slavery undergirded the phenomenal success of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Stowe was a child of the venerable Beecher family, who had long been stalwarts of New England church life. Her father, Lyman Beecher, was a moderate Calvinist pastor, a great combatant of Unitarian theology, and an activist for temperance reform. Stowe’s sister Catharine was a key player in the crusade against Indian removal in the 1830s. But Stowe became perhaps the best-known person in her large family because of her antislavery novel. Uncle Tom’s Cabin captured many white and black northerners’ fears about the Fugitive Slave Act, a major feature of the Compromise of 1850, which empowered southern whites to track down anyone suspected of being a runaway slave in the northern states. One of the most affecting parts of the novel saw the slave Eliza and her child running away from their master, who had agreed to separate them in a sale. Uncle Tom’s Cabin first appeared as a newspaper serial. Within a year of its release as a book, it had sold more than 300,000 copies.

Stowe is not as well-known for her more theological novels. But after Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she also mused on the Calvinist faith of her upbringing. In The Minister’s Wooing (1859), Stowe raised questions about the eternal fate of the upstanding but apparently unconverted fiancé of the novel’s heroine. (Stowe and her family had endured repeated tragic deaths that provoked the same kind of questions about unconverted loved ones.) Was the fiancé lost forever in hell by God’s eternal decree? A traditional Calvinist pastor tells the fiancé’s grieving mother that if the fiancé is eternally condemned, it is by God’s plan and for the greater good. The mother angrily rejects this notion. “It is not right!” she announces. She wildly declares that she can no longer love God if predestination is true. “No end! No bottom! No shore! No hope! O God! O God!” she cries. Such attacks on Calvinism held the seeds of a rejection of the traditional Christian belief in hell or a rejection of biblical authority altogether.

Theological Liberals and the Transcendentalists

Stowe was hardly alone in her reaction against Calvinism. Although everyday Americans remained largely untouched by skeptical intellectual trends, in the 1810s and ’20s, the principles of Unitarianism, Universalism, and other heterodox movements were gaining traction, particularly among elite New Englanders. The exaltation of human reason birthed more and more criticism of traditional Calvinism and trinitarian doctrine. William Ellery Channing, a prominent Boston minister, delivered a sensational defense of Unitarian theology in 1819, at the opening of a new Unitarian church in Baltimore, Maryland. No other book, Channing insisted, “demands a more frequent exercise of reason than the Bible.” Reason demanded rejection of the Trinity and the notion that Jesus was part of the Trinity. Channing similarly rejected predestination and the belief that Jesus’s death atoned for the sins of believers. Channing’s controversial sermon became the most-read American publication since Tom Paine’s Common Sense (1776).

Traditionalist Christians offered serious challenges to Channing’s theology. Among them was Moses Stuart, the most accomplished biblical scholar of the era. Stuart taught at Andover Theological Seminary in Massachusetts, which had been founded as an orthodox alternative to Harvard’s growing theological liberalism. Stuart chided Channing for prioritizing reason over revelation. Stuart thought the Unitarians were really seeking to determine, via “common sense,” which doctrines are true and which ones false. Only then did they seek to prove that the Bible did not teach doctrines such as the Trinity. Stuart agreed that we should use reason as an aid to interpreting the Bible. But whatever the Bible taught Christians must believe. In spite of criticisms from Stuart and others, the tide of theological liberalism was hard to stop. Harvard had become committed to Unitarian theology by 1805. Even Andover Seminary had embraced such theological liberalism by the late nineteenth century.

Three years after Channing’s Baltimore sermon, Thomas Jefferson predicted that “there is not a young man now living in the United States who will not die a Unitarian.” This prediction was laughably wrong. Unitarians never became numerous in America, but their theological and cultural influence far outpaced their numbers. Elite institutions such as Harvard always put a premium on being on the leading edge of thought and learning, so theological liberalism and “higher criticism” often caught on fastest at the colleges with the most “symbolic capital,” or weight of societal authority. Unitarian theology also had enormous impact on intellectual and literary trends of the antebellum period. Many of those trends emerged from Concord, Massachusetts, the home of Transcendentalism.

A formidable cadre of literary talent came out of Concord during the antebellum era, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Louisa May Alcott, Margaret Fuller, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. It was remarkable that a modest farming village such as Concord could produce such a list of writers in a short period of time. We may partly account for this phenomenon by remembering that Concord was near the academic influences of Harvard and the relatively cosmopolitan world of Boston. Concord still offered pastoral scenes of inspiration, not least Thoreau’s Walden Pond. The natural world was a major focus of the broader Romantic movement, of which Transcendentalism was a part. The Transcendentalists shared a desire to “transcend” religious tradition and suffocating social norms to find authentic harmony with God. Most of the Transcendentalists began as Unitarians, but some of them abandoned any pretense of remaining within the Christian tradition.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, for example, started off as a pastor at a Unitarian church in Boston. But he became increasingly disillusioned even with Unitarian church rituals, so he resigned and styled himself an intellectual, writer, and prophet of a new Transcendentalist faith. Emerson taught that nature was suffused with divine presence. Harmony with nature led humans into the life of God, whom he sometimes called the “Oversoul.” There was no fundamental need for mediation by a church or a holy book in Emerson’s piety—just the individual and God, as encountered in the natural world. In Emerson’s 1838 “Divinity School Address” at Harvard, he shocked even Unitarians by dismissing the importance of the biblical accounts, including miracles. “To aim to convert a man by miracles, is a profanation of the soul. A true conversion, a true Christ, is now, as always, to be made, by the reception of beautiful sentiments,” Emerson declared. He encouraged the pastors-in-training to “go alone” and to embrace their role as a “newborn bard of the Holy Ghost.” Conservative Princeton Seminary professors responded by saying they lacked “words with which to express our sense of the nonsense and impiety which pervades” Emerson’s address.

Literary dynamo Margaret Fuller was perhaps the best example of the activist strain of Transcendentalism. The daughter of a Massachusetts congressman, Fuller was one of the best-educated women of the era and could speak six languages. Emerson recruited her to edit the Transcendentalists’ literary magazine, the Dial. Fuller hosted regular tutorials to help educate local women in a time when formal education for women remained limited beyond the standard of basic literacy. Her feminist text, Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845), insisted that exclusive ideas about gender unnecessarily limited women’s vocational opportunities. She herself broke a vocational mold when she became one of the leading writers for Horace Greeley’s influential New York Tribune in 1844. The Tribune sent her to Europe as a foreign correspondent, where she covered widespread political upheavals on the continent in 1848. She established a relationship with an Italian man and had a child by him. But when the three of them traveled to America in 1850, they died in a shipwreck off the coast of New York.

Henry David Thoreau made his mark on Transcendentalism because of his stint in the 1840s living in a cabin on Concord’s Walden Pond, on property Emerson owned. For Thoreau simplicity was the key to transcending the dulling effects of conventional American life. “To be awake is to be alive,” Thoreau wrote, but he had “never yet met a man who was quite awake.” Why did he go live in the woods? “Because I wished to live deliberately,” he said, “to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

Aside from his themes of simplicity and living in nature, Thoreau is remembered for his essay “Resistance to Civil Government” (1849), commonly called “Civil Disobedience.” In it Thoreau reflected on the night he spent in the Concord jail in 1846 for refusing to pay a Massachusetts poll tax. Thoreau insisted that individuals should disobey laws that violated universal moral principles. If government “requires you to be the agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law. Let your life be a counter-friction to stop the machine,” he wrote. Thoreau’s views went on to inspire resistance movements such as Mohandas Gandhi’s in India and Martin Luther King Jr.’s campaign for civil rights.

Some Transcendentalists became disillusioned with the movement’s radicalism. One of the most striking examples of this disillusionment was Orestes Brownson. Brownson served as a newspaper editor and a Unitarian minister. Over time Brownson became most interested in socialist politics and defending the interests of the new industrial working classes. He controversially wrote that northern factory workers were actually treated worse than African American slaves in the South. Brownson was never comfortable with the radical individualism and irreligious tendencies of Emerson’s theology, however. Brownson shocked the Transcendentalists in 1844 by doing something truly original: he converted to Catholicism! The Church of Rome would seem to have been as far from Emerson’s naturalist individualism as Brownson could have gone. Brownson came to believe the basic problem with the Transcendentalists was their naïve belief in “unrestricted private judgment. They reject the authority of the church, the authority of the Bible, of the apostles, of Jesus—nay, all authority but that of the individual himself.” Brownson averred that people needed both revelation and church tradition to understand the truth about God and the Bible. Brownson went on to become the most articulate defender of Catholicism in nineteenth-century America.

Concord and Transcendentalism also put their mark on a new age of American novel writing. Concord’s great fiction writer Nathaniel Hawthorne was reacting against his family’s Puritan heritage in much of his work, especially his best-known novel The Scarlet Letter (1850). In it Hawthorne told the story of Hester Prynne, who is publicly shamed for conceiving a daughter in an adulterous relationship. Prynne searches for a way out from under the “dismal severity of the Puritanic code of law.” Hawthorne’s novel, along with Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible, shaped a negative stereotype of the Puritans for generations of American students.

Hawthorne’s friend Herman Melville may have produced the greatest novel of the era’s “American Renaissance” with his 1851 Moby-Dick. This complex but compelling book seemed torn between Transcendentalist impulses and the power of the Calvinist legacy, which Melville had learned from his devout mother and the Dutch Reformed Church of his youth in New York. Captain Ahab’s obsessive quest to destroy the white whale is ultimately foiled by the eerie power of the whale itself. In the final confrontation the whale’s “predestinating head” wrecked the ship. “Retribution, swift vengeance, [and] eternal malice were in his whole aspect, [in] spite of all that mortal man could do,” Melville wrote. The dark ambivalence of Moby-Dick reflected Melville’s own struggles with faith. Hawthorne wrote that Melville was constantly assailed with concerns about “Providence and futurity. . . . He can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other.”

One of the greatest southern writers of the antebellum era was Edgar Allen Poe. Born in Boston, Poe was orphaned early and taken in by a family in Virginia. As his writing career proceeded, he cast himself as a philosophical opponent of the Transcendentalists. Poe became one of America’s masters of poetry, short stories, and literary criticism. He might have done much more had he not died at the age of forty from ailments undoubtedly exacerbated by his alcoholism. Poe was best known for his chilling 1845 poem “The Raven,” in which a mysterious raven exacerbates the narrator’s grief over lost love. The raven is apparently only able to say the word “nevermore,” which it keeps repeating in response to the narrator’s queries. The narrator becomes exasperated and cries out in despair, quoting a famous question from the prophet Jeremiah.

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there—is there balm in Gilead?—tell me—tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

Poe was contemptuous of the Transcendentalists’ optimism about human autonomy and divine potential. He also raged against what he regarded as the snobbishness of the Boston-area literary scene, especially their disdain for southern writers. Poe scoffed at the “miserable bedlamites in BOSTON—a clique of pitiable dunderheads, who go about babbling in parables.” They were, he concluded, a “set of thumb-sucking babies and idiots.”

The great figures of the American Renaissance enjoyed only occasional commercial and popular success. Because of the emerging crisis over slavery in the West and over the Fugitive Slave Act, the popular market for literature—at least in the North—was becoming focused on slavery and America’s future. In this genre the greatest southern author was Frederick Douglass. In addition to his popular autobiography of 1845, the former slave became arguably the greatest abolitionist orator and essayist. His speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” delivered on Independence Day in 1852, raised hard questions about how white Americans excluded blacks from the blessings of liberty. But it also called on Americans to live up to the principles of equality that Douglass hoped they could find in the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Bible.

On that Fourth of July, Douglass proclaimed that he heard “the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them.” Citing Psalm 137:5–6, he told the audience:

If I do forget, if I do not faithfully remember those bleeding children of sorrow this day, “may my right hand forget her cunning, and may my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth!” . . . The character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July! Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future. Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible, which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery—the great sin and shame of America!

Black and white abolitionists denounced slavery and the Slave Power in ever-louder tones after the Compromise of 1850. It remained to be seen what course slavery and freedom would take in the nation’s future.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass’s Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989.

Bowman, Rex, and Carlos Santos. Rot, Riot, and Rebellion: Mr. Jefferson’s Struggle to Save the University That Changed America. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013.

Goen, C. C. Broken Churches, Broken Nation: Denominational Schisms and the Coming of the American Civil War. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1985.

Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

Gutjahr, Paul C. Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Hamburger, Philip. Separation of Church and State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Koester, Nancy. Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Spiritual Life. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014.

Marsden, George M. The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Noll, Mark A. America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Turpin, Andrea L. A New Moral Vision: Gender, Religion, and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education, 1837–1917. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016.