19

The Progressive Era

The Progressive Era, which lasted from the 1890s to the 1920s, was inspired by the conviction that America’s ills could be solved by hard work, creative planning, and moral zeal. One of the reformers’ most basic tasks was to bring the darker aspects of American life to light in order to touch the consciences of average middle-class Americans. The “muckrakers,” those journalists and writers who sought to expose the abuse of American workers and the plight of America’s poor, specialized in stories that stirred Americans’ hearts with compassion for America’s downtrodden classes.

One of the most effective exposés was novelist Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906), which revealed horrid conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking plants. Sinclair painted revolting scenes of butchers with swollen joints and missing fingers and “men who worked in the cooking-rooms, in the midst of steam and sickening odors, by artificial light; in these rooms the germs of tuberculosis might live for two years, but the supply was renewed every hour.”

The conditions were worst of all for the men who worked at the enormous cooking vats. “Their peculiar trouble was that they fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting. Sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as ‘Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard!’” Sinclair’s account was so sickening that he worried that he had failed in his muckraking aims. He wanted to draw the nation’s attention to the “wage-slaves” in the food industry, but instead all the focus went to the horrific corruption of the food supply. “I aimed at the public’s heart,” Sinclair confessed, “and by accident I hit it in the stomach!” From the factories to impoverished farms, and from immigrant ghettos to the cotton plantations, Progressives saw outrages that demanded action.

Changes in American Industry

The American economy had begun to recover from the depression caused by the Panic of 1893. The continued growth of American industry in the early 1900s created difficult and dangerous conditions for many workers, especially recent immigrants, the poor, and the uneducated. The scale of American business continued to escalate and consolidate in the early decades of the twentieth century, creating behemoths such as J. P. Morgan’s U.S. Steel Corporation.

New technologies kept revolutionizing the marketplace too. Perhaps the most distinctive technological change in the early years of the 1900s was the coming of the automobile. The key figure in the automobile industry was Henry Ford, the child of Irish immigrant farmers who grew up in Dearborn, Michigan, outside Detroit. In Detroit, Ford went to work for the Edison Illuminating Company, where he learned from Thomas Edison’s vision of pairing invention and the production of consumer products. Ford was a talented engineer and machinist, and in 1896 he unveiled his prototype car, called the Quadricycle. In 1903, he founded the Ford Motor Company, believing he could design cars that would be affordable for middle-class American families. “I will build a car for the great multitude,” he said. “It will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one—and enjoy with his family the blessings of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.” Until that point automobiles were exotic luxuries. In 1895, only four cars total were operating on the nation’s roads.

Although Ford’s Model N car was a commercial success, in 1908 he introduced the Model T, a product that would permanently transform American life. His company produced 6,000 Model Ts in 1908, each selling for $850. As Ford streamlined the production process, he ratcheted up the number of cars he was making and slowly dropped the price. By 1916, Ford Motor Company was making almost 600,000 cars a year and selling them for $360 each. Along with competitors like General Motors and Chrysler, Ford not only revolutionized American transportation but also transformed many other sectors of the economy. Demand shot up for gasoline, oil, rubber, and other car-related products. The landscape of American towns and highways changed, with shops lining newly paved roads. Traffic signals coordinated the unprecedented flow of automobile traffic passing through cities.

Ford realized that the traditional way of making machinery like a car, with a small number of craftsmen working on each stage of assembly, was inefficient. His factory standardized each stage of the car production process to make it quick and reliable. Individual workers each performed a simple task, like turning bolts or putting on a single part of the automobile. Ford also installed conveyer belts so the cars moved automatically down the assembly line to the next task station. Workers no longer moved from their stations. The car came to them. By 1920, Ford factory workers could construct a Model T in one minute.

Like many industrialists, Ford feared worker unrest and union movements. So he decided in 1914 to raise his factory laborers’ pay to five dollars per eight-hour workday. At the time this was triple the average amount an industrial worker was making in America, and Ford figured that it would help him attract and keep the best workers. All his innovations made Ford the pioneer of mass production. In 1923, 2 million Model Ts rolled off Ford assembly lines.

Corporations, trusts, and other large businesses were the only ones that could invest in the kinds of infrastructure, equipment, and laborers required to perform mass production of affordable products. Local craftsmen and small-shop industries became less and less common. On the eve of the Great Depression of the 1930s, incorporated businesses were responsible for making 92 percent of the manufactured goods in America. The 200 largest corporations held a fifth of America’s combined wealth.

Mass Production and the Workers

Some workers, like the higher-paid ones at the Ford factory, benefited from the expansion of mass production. Others found the transition challenging at best. The simple nature of mass-production factories meant that an individual worker ideally learned to do just one task as expertly and quickly as possible. If that meant turning one bolt on one car part countless times a day, that meant more efficiency. But many workers found that kind of work mind-numbing. (Part of the reason Ford raised wages in 1914 was because they were already seeing massive rates of turnover among the workers.) Increased efficiency could also make old-fashioned jobs superfluous, leading to layoffs. Other factory employees, like Upton Sinclair’s meatpackers, found themselves working in extraordinarily dangerous conditions.

The dangers for factory workers were illustrated by the horrors of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 in New York City. The fire began on the eighth floor of a ten-story building. There a labor force made up mostly of immigrant Jewish women sewed “shirtwaists,” a popular kind of women’s blouse. The fire was of uncertain origin, but it swept through the factory and its abundant supply of flammable materials. Lacking any kind of modern alarm or fire-extinguishing equipment, the panicked workers found many of the factory doors locked, as owners were trying to cut down on unscheduled breaks, thievery, and unwelcome guests. An elevator and a fire escape were both inoperable at the time of the fire. The New York City fire department was ill-equipped to counteract a blaze so high up in a building. Desperate women leapt to their deaths out of factory windows. Some of those left inside were burned beyond recognition. One hundred forty-six shop workers died in the conflagration. Many of the dead were teenagers. Factory owners were charged with manslaughter, but they were acquitted. They settled charges in a civil lawsuit by paying seventy-five dollars for each dead worker.

Eighty thousand people marched in the New York City funeral procession for the Triangle factory workers. A twenty-nine-year-old labor organizer named Rose Schneiderman said that the good wishes of civic and religious leaders in the city did nothing to help. Though the Triangle fire was one of the worst industrial accidents in American history, Schneiderman argued that it was hardly exceptional. “Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers,” she said. “Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death. . . . It is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.”

Figure 19.1. Rose Schneiderman, between 1909 and 1920.

Although episodes like the Triangle fire did inspire some reforms in workplace safety, the early 1900s were not an era of growth for the labor union movement. Corporations such as Ford Motors were successful at adopting strategies to keep unions at bay. The prosperity of the 1910s and 1920s also meant that joining a union seemed less urgent to many workers. Key Supreme Court decisions weakened legislative and constitutional protections for workers too. One of the most significant decisions was Lochner v. New York (1905), which struck down a New York law that had tried to cap the maximum allowable working hours for employees at bakeries. The court’s majority argued that this kind of law violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of “due process” and an individual worker’s right to make contracts of his or her choosing.

Legal historians often call the next three decades of Supreme Court jurisprudence the “Lochner era” because of a series of decisions that tended to favor business owners over workers and that limited the effectiveness of unions. In decisions such as Loewe v. Lawlor (1908), known as the “Danbury Hatters’ Case,” the court sometimes applied antitrust legislation to the efforts of unions and workers to boycott companies that prohibited union organizing. Antitrust legislation, including the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890), was originally designed to break up monopolies that suppressed competition. In cases such as Loewe, however, the court applied antitrust principles to forbid groups such as the United Hatters union and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) from organizing national boycotts against nonunionized companies. Doing so, the court contended, violated such companies’ ability to participate freely in interstate commerce. The court also made clear that individual workers, not just their unions, could be held financially accountable for violating antitrust provisions. This had a chilling effect on workers’ willingness to get involved in strikes and boycotts.

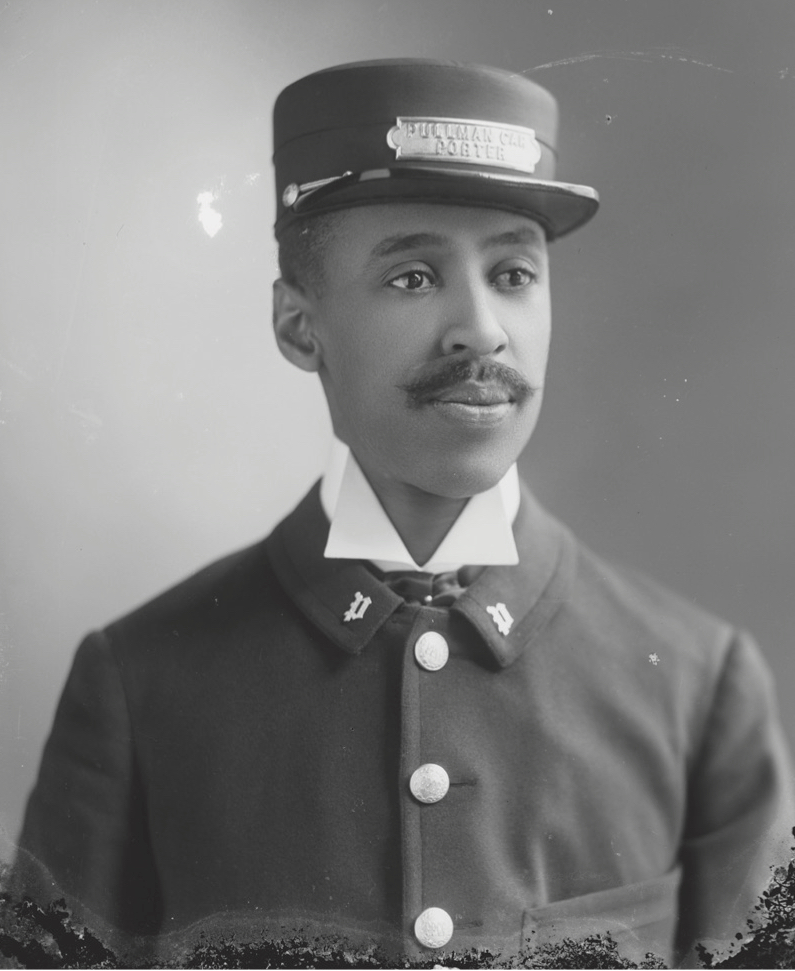

The labor union movement was also hampered by internal divisions. Some groups—for instance, the Industrial Workers of the World (the “Wobblies”)—were openly radical and socialist. Socialists sought to recruit unskilled workers, nonwhites, and women, segments of the working population that organizations such as the AFL tended to ignore. Early efforts at organizing more marginalized workers resulted in unions for women, such as the Women’s Trade Union League, or for African Americans, such as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, organized in 1925 by A. Philip Randolph. Randolph was influenced by the writings of nineteenth-century German philosopher Karl Marx, who had addressed the perpetual struggle between capital and labor. But the horrors of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in the 1910s sobered Randolph, who became an outspoken anti-communist even as he sought to organize African American railway workers.

Figure 19.2. J. W. Mays, Pullman car porter.

In a 1926 speech on the sesquicentennial of the Declaration of Independence, Randolph cited the Declaration’s principle that “all men are created equal” and insisted that blacks should share fully in that ideal. To those who would exclude African Americans, Randolph declared that the “Negro is, doubtless, the most typically American. He is the incarnation of America. His every pore breathing its vital spirit, without absorbing its crass materialism.” But blacks were also the most exploited workers in American history. So Randolph predicted that “the Negro’s next gift to America will be in economic democracy. . . . Experience and necessity are teaching him of the value of labor organization. . . . This will rescue him from the stigma of being regarded by organized white labor as the classic scab of America.” In 1929, Randolph would affiliate the Sleeping Car Porters union with the AFL, tapping into the broader national power of the white-led labor movement. In 1937, the Sleeping Car Porters union also won a labor contract with the Pullman Company, the key employer of the brotherhood’s members.

Immigration

Waves of new immigrants kept supplying much of the unskilled, and least unionized, segments of the American workforce. Since 1900, much of that immigration was coming from southern and eastern Europe and from Mexico. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, a record-setting 14.5 million immigrants arrived in the United States. Some of these came as entire families, with no plan to return to their place of birth. Some immigrants came by themselves, hoping to earn money to help their families back home or to earn money in America that would help them get established once they returned to their land of origin. Companies like Ford offered English-language instruction and courses on American culture to help immigrant employees get acclimated. But some union activists believed these courses were mainly intended to produce compliant workers. On the West Coast, Japanese immigration outpaced Chinese because of laws specifically prohibiting Chinese settlement. By 1920, more than 100,000 Japanese people lived in the United States, mostly in California.

Mexican immigration had begun to pick up after 1900, especially as southwestern ranches, farms, and businesses needed more labor to replace the excluded Chinese. Then in 1910, the Mexican Revolution began with the ouster of Mexico’s longtime ruler Porfirio Díaz. The Mexican Revolution would continue to convulse the nation for ten years as Mexico went through multiple revolutionary regimes. The violence and instability sent tens of thousands of Mexican immigrants across the US border. There was no effort to tally up US border crossings until 1907, and there was no border patrol until 1924. Thus, the numbers of immigrants and of Hispanics living in the United States were difficult to track. Nevertheless, the total number of Mexican-born people in the United States probably went from fewer than 5 million in 1900 to about 15 million on the eve of the Great Depression in the late 1920s. They spread out across the country from Alaska to the East Coast, but the preponderance of Mexican immigrants lived in the Southwest, from California to Texas.

In the southwestern states, the number of Mexicans was often doubling every decade between 1900 and 1930. In some places the growth was even faster. Mexicans often settled in barrios, or Mexican-majority sections of southwestern towns. The barrio in El Paso, Texas, was called Chihuahuita, a name derived from the Mexican state that lay directly south across the Rio Grande. Chihuahuita grew quickly from the 1890s forward, with most adult men in the neighborhood working in the railroad industry. Others used barrios such as Chihuahuita as a transit point: once having crossed the border into the United States, Mexican workers might fan out to wherever they could find seasonal work and then return to the border town in the off-season. A visitor to Chihuahuita in 1900 noted that most of the Mexicans there lived in dirt-floor adobe huts with outhouses and little sanitation.

Christian churches and missionary organizations worked to alleviate some of the problems in the barrios, offering spiritual help and social assistance of various kinds. St. Ignatius Catholic Church was one of the key parishes serving the Chihuahuita neighborhood, whose residents were overwhelmingly from a Catholic background. Tens of thousands of Catholic Mexicans would participate in Corpus Christi parades each June in the 1910s in El Paso. Protestants also sought to make inroads, and by the early 1900s virtually every major Protestant denomination had founded a church designed to reach out to El Paso’s Mexicans. Probably more successful than the churches were the efforts of the YMCA to attract young Mexicans in Chihuahuita. The YMCA offered Bible and English-language classes as well as various sports leagues and other forms of entertainment. Although much of this activity was designed to foster “Americanization,” the YMCA did put Mexican Americans in leadership positions. It also accommodated Mexican culture by sponsoring events such as a Cinco de Mayo celebration each May. By 1920, tens of thousands of Mexicans were participating in YMCA functions in El Paso.

White-owned businesses were eager to use Mexican labor, but many whites expressed concern about the cultural and racial influences Mexicans brought to America. In particular, white men worried about Mexican men and their potential desire to marry white girls. One Los Angeles agricultural official during the era assured constituents that Mexicans “don’t try to marry white women” (though he thought that Filipino men did try to do so). A San Diego school superintendent was not so sure, saying that “American parents don’t want their lily-white daughters rubbing shoulders with the Mexicans with their filthy habits.” Such sentiments encouraged the segregation of Mexicans into their own schools and neighborhoods in the Southwest.

Progressives

The Progressive movement responded to a host of issues raised by rapid urbanization, industrialization, and immigration. Progressivism was a large and not always consistent movement. It ran the gamut from admirable causes, such as alleviating the worst abuses of factory workers, to troubling ones, such as restricting the birth rates of “undesirable” races. Progressives worked in political offices, journalism, academia, churches, and social relief agencies.

Progressives focused on at least three major areas of social reform. One was regulating big industry and business. The successes of companies like Ford Motor and Standard Oil depended on the freedom of businesses to grow and compete as they saw fit. But Progressives argued that there came a point where business success undermined human dignity and the public good. Theodore Roosevelt declared that the government must resist those businessmen who believe that “every human right is secondary to his profit.” Progressives argued for reforms of child labor practices, workplace safety, and the maximum working hours and minimum pay laborers could expect. Some Progressives believed the government must take an active role in breaking up monopolies for the good of the economy and the individual consumer.

A second major focus of Progressives was ensuring responsive, democratic government. In this priority they drew on parts of the legacy of Populism from the late 1800s. Progressives lamented corruption in politics and the power of Democratic and Republican party operatives over the people at large. They sought to put more political power in the hands of more people, advocating for causes such as the direct election of US senators and the right of women to vote.

Finally, Progressives sought to address the problems created by immigration, urban crowding, and poverty. Some initiatives took a positive approach, offering basic services to the urban poor and to immigrant newcomers. The settlement house movement encouraged education, job training, health, and safe living conditions. Some reforms took a more negative approach, seeking to restrict immigration, especially of Jews, Catholics, and Asians. Others sought moral reforms that seemed especially pressing among the urban population, such as prohibiting the sale and consumption of alcohol. Progressives were often split among themselves on issues such as racial integration and voting rights for nonwhites. Many of the Progressives’ concerns were not new in American history, but the Progressive movement became the first nationwide effort at systematic reform since crusades such as the temperance cause of the pre–Civil War era.

The Progressives produced a remarkable cadre of female leaders, pioneered by Frances Willard, the leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which had already become the nation’s largest women’s organization by the 1890s. Jane Addams’s Hull House in Chicago also cultivated key female leaders in the Progressive movement. One of them, Florence Kelley, lived at Hull House for much of the 1890s before becoming the head of the National Consumers League from 1899 to 1932. Kelley’s organization campaigned for labor and educational reform but was especially known for restricting the use of young children as laborers in factories.

Kelley, who was influenced by European socialist thought, explained the tumultuous changes coming to America if the nation did not give due attention to suffering workers:

We are nearing the point at which the blind movement of industrial development must involve us in utter social chaos, the means of production all concentrated in a few irresponsible hands . . . the army of the unemployed swollen to such proportions as to burden and cripple all industry. . . . The old order of society is passing away, the new has yet to be evolved. The transition may excel the horrors of the French Revolution, or be ushered in as calmly as the dawning of the day. That will depend upon the insight of the workers and the women of the nation.

To ease the transition, Kelley insisted, the children of even the poorest Americans must have access to public schooling. Americans should not allow children, forced by economic need, to go into the factories at an early age, which was common in the late 1800s. In a successful national campaign, Kelley’s league also put labels of approval on consumer products from companies that did not exploit workers or children.

New experts like Kelley (who earned a law degree from Northwestern) touted scientific analysis as key to alleviating social ills. They performed unprecedented surveys of cities such as Chicago and New York, documenting patterns of poverty and unsanitary conditions. Although some Progressives still emphasized that no one could hope to escape poverty without making good individual choices, many of the new reformers pointed to structural and generational causes of the impoverished classes’ struggles.

The studies of poverty reflected a broader trend toward creating academic, scientific, and professional societies of all kinds across America. Hundreds of such societies were founded between the end of Reconstruction and the US entry into World War I. Among the most influential was the American Bar Association (1878), which has set many standard practices for the law profession. The American Medical Association (AMA) had been founded in 1847, but a 1901 reorganization of it helped turn the AMA into a major advocate for standardized protocols of doctors’ care and use of medication. Because of its focus on “professional” medicine, the AMA has also historically been resistant to the recognition of “alternative” medical practices, such as naturopathy and chiropractic treatments.

The Muckrakers

One of the most powerful tools of the Progressive movement was publishing. The men and women who wrote exposés of the abuses in industry and politics were labeled “muckrakers” in 1906 by Theodore Roosevelt. This was initially a negative term that referenced the character of the “Muck-raker” in John Bunyan’s spiritual classic The Pilgrim’s Progress. Although Roosevelt had his own Progressive inclinations, he thought that some muckraking authors were too negative about the corruption and exploitation in America. But muckrakers such as Upton Sinclair and Ida Tarbell (the nemesis of John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil) found a ready audience for their work in popular newspapers, magazines, and books. The muckrakers spun lurid and sensational but usually fact-based stories about the appalling suffering in the nation’s cities and leading industries.

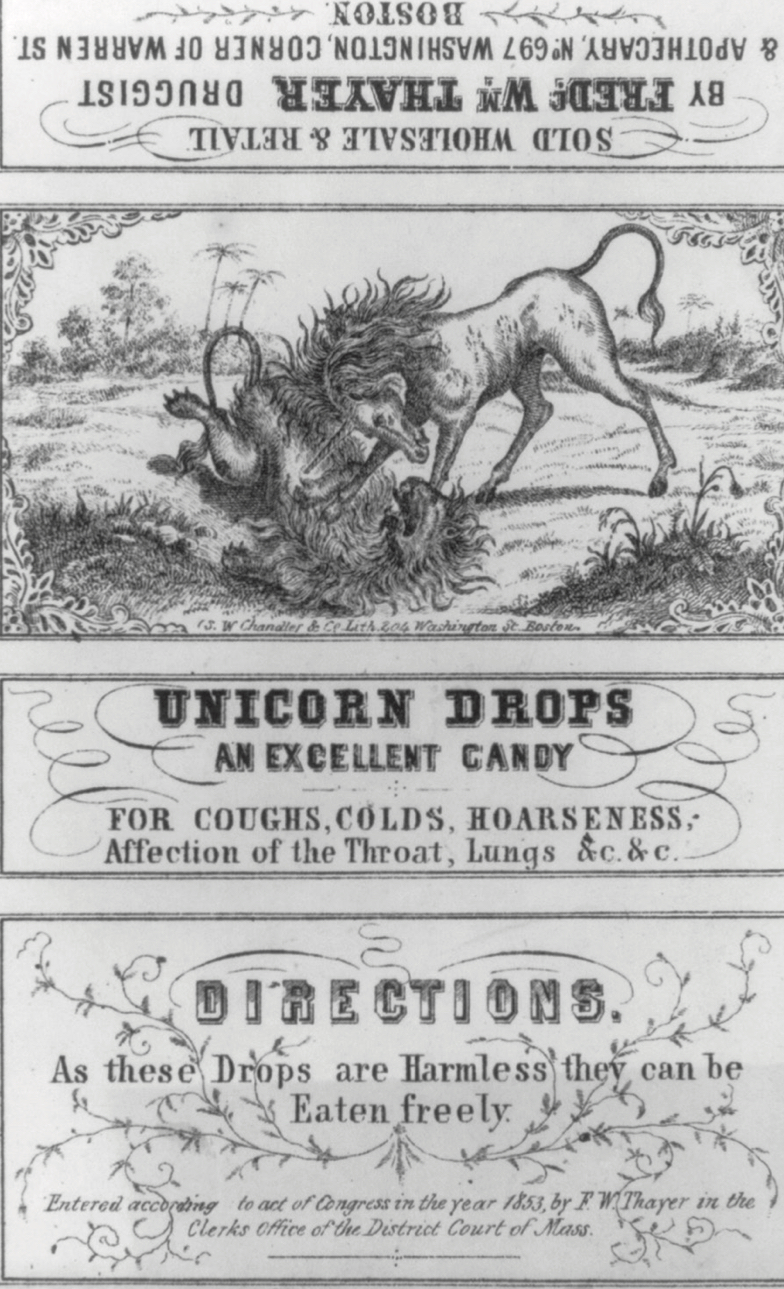

Writers such as Samuel Hopkins Adams lambasted the producers of patent medicines that were laced with alcohol and cocaine, which might bring temporary relief but also bred false hopes and addiction. Writing in Collier’s Weekly, Adams exposed the “Great American Fraud” of the popular remedies, including

the alcohol stimulators, as represented by Peruna, Paine’s Celery Compound, and Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey (advertised as an exclusively medical preparation); the catarrh powders, which breed cocaine slaves, and the opium-containing soothing syrups, which stunt or kill helpless infants; the consumption cures, perhaps the most devilish of all, in that they destroy the hope where hope is struggling against bitter odds for existence; the headache powders, which enslave so insidiously that the victim is ignorant of his own fate; the comparatively harmless fake as typified by that marvelous product of advertising and effrontery, Liquizone; and finally, the system of exploitation and testimonials upon which the whole vast system of bunco rests, as upon a flimsy but cunningly constructed foundation.

Adams’s work prompted the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which required that commercially sold medicines list their ingredients on the label. Another law in 1914 greatly reduced the use of cocaine and opium in common medicines.

The Social Gospel

As we have seen, by the late 1800s some American Christians were adopting the “Social Gospel,” or the belief that Christianity was best lived out in loving service. The Social Gospel blended with the spirit of Progressivism in the early 1900s. Social Gospelers believed that all Christians should seek the good of the most troubled communities and people in the nation. Some Christians went so far as to espouse socialism. Some of the same kinds of people attracted to the Populist movement of the late 1800s gravitated toward socialist principles. For example, in Oklahoma and other parts of the Great Plains, socialist candidates received the most support from Pentecostals and Primitive Baptists. These denominations tended to appeal to working-class Christians anyway, and some who felt left out of the burgeoning capitalist system combined the messages of Christianity and socialism. They scoffed at the more affluent denominations’ religion as the “church of greed.” One socialist appealed to ministers by saying that the time for choosing your allies was at hand: “If you are with the crowd that Jesus drove from the temple, you will have to show it, and if you want to come out from among the thieves and money changers and join the battle for humanity it’s time to show your hands.”

Figure 19.3. “Unicorn drops” medicine, ca. 1853.

The most famous Social Gospel advocates were not Great Plains farmers, however, but eastern Protestant theologians and pastors. Walter Rauschenbusch, a Baptist professor at Rochester Theological Seminary, produced some of the key works on the Social Gospel, including Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907). Instead of viewing Jesus’s teachings as focused on individual salvation or the afterlife, Rauschenbusch insisted that Jesus’s ethics were meant for the here and now. Christians should be known for working on behalf of the “least of these” (see Matt 25:31–46) and for economic equality and fairness. “Christianizing the social order,” Rauschenbusch explained in 1912, meant “bringing it into harmony with the ethical convictions which we identify with Christ. . . . These moral principles find their highest expression in the teachings, the life, and the spirit of Jesus Christ.” Of broader impact was the phenomenally popular novel In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do? (1896) by Congregationalist pastor Charles Sheldon. The book told the story of how a town was revolutionized when its citizens took up the challenge of asking, “What would Jesus do?” before taking any action. Sheldon’s novel went on to sell tens of millions of copies.

Although many of the Social Gospel advocates came out of traditional Christian backgrounds, the movement also became associated with some pastors who de-emphasized or even denied essential Christian beliefs. Some of the Social Gospel’s leaders, such as Congregationalist pastor Washington Gladden, positioned themselves as foes of the emerging “fundamentalist” Christian movement. For example, Gladden denied the infallibility of the Bible. He acknowledged that as of the late 1800s, the “great majority of Christians” believed in the Bible’s perfection and infallibility. But “intelligent pastors do not hold it,” Gladden said. This sort of critical view of the Bible led many fundamentalists to view the Social Gospelers with skepticism. As an essay in The Fundamentals put it, the church should indeed proclaim the “social principles of Christ.” But that did not “mean the adoption of a so-called ‘social gospel’ which discards the fundamental doctrines of Christianity and substitutes a religion of good works.”

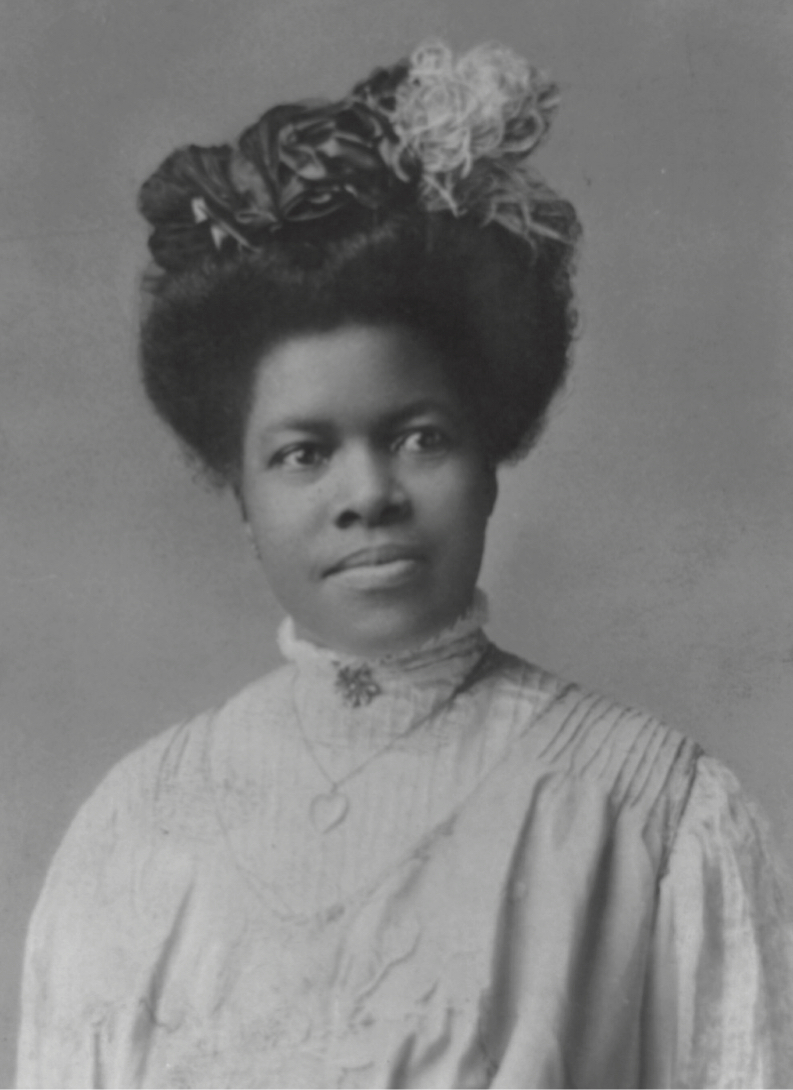

African American Social Gospel advocates were often influenced by the debates between W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington and disagreed among themselves about the best approach to black “uplift” in the era of Jim Crow. Leaders of the Women’s Convention of the National Baptist Convention (NBC), for example, called not only for equal treatment of women and African Americans but also for alleviating the struggles of the urban poor and factory workers. The Women’s Convention, the largest organization for black women at the time, was also evangelistic, sending missionaries to Africa and elsewhere. In her 1900 speech “How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping” at an NBC meeting, the Woman’s Convention founder and leader, Nannie Helen Burroughs, declared, “For a number of years there has been a righteous discontent, a burning zeal to go forward in [Christ’s] name among the Baptist women of our churches and it will be the dynamic force in the religious campaign at the opening of the 20th century. It will be the spark that shall light the altar fire in the heathen lands.” Burroughs recruited Booker T. Washington as a regular keynote speaker for National Baptist women’s meetings.

Progressives and Race

In addition to concerns for the unfair treatment of the poor and other groups, black Progressives and muckrakers carried the additional burden of protesting the treatment of African Americans. Although many black workers were poor too, blacks also dealt with the additional burdens of segregation, disenfranchisement, and lynchings. Thousands of African Americans were murdered by lynching in the last two decades of the 1800s, with many of the victims subjected to torture in public spectacles. Ida B. Wells, a teacher and journalist in Memphis, gained notoriety in 1892 when she published the anti-lynching exposé Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. Wells not only documented many instances of lynching but insisted that the strategy of hoping to appeal to white people’s consciences was an insufficient plan of resistance. Under the category of “Self-Help,” Wells noted that the only way blacks had averted lynchings was when they took up arms in self-defense. A “Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home,” Wells concluded. “It should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give. When the white man who is always the aggressor knows he runs as great risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life.” Wells suggested that the common accusation of black men raping white women was a myth.

Figure 19.4. Nannie Helen Burroughs, between 1900 and 1920.

Many whites were outraged by Wells’s provocative publication. One newspaper declared that “the fact that a black scoundrel is allowed to live and utter such loathsome and repulsive calumnies is a volume of evidence as to the wonderful patience of Southern whites. But we have had enough of it.” A Memphis newspaper openly called for the editors of Wells’s newspaper, the Free Speech and Headlight, to be lynched themselves. Whites wrecked the office and equipment of the newspaper in 1892. Fortunately for Wells, she was attending a conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia when the attack happened, or she might have also become a victim. Realizing the risks of staying in Memphis, Wells permanently relocated to Chicago.

African Americans wanting a more aggressive approach to civil rights organized the Niagara Movement in 1905. Led by W. E. B. Du Bois, the group adopted a platform committed to “full manhood suffrage” (keeping distance from women’s suffrage), the “abolition of all caste distinctions based simply on race and color,” and the “recognition of the highest and best human training as the monopoly of no class or race.” That last point was a swipe at the views of Booker T. Washington. Washington opposed the Niagara Movement as a threat to his dominant role in the African American community.

The Niagara Movement struggled to gain traction and ceased to exist after several years. Of more enduring significance was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909 by black and white leaders, including Ida B. Wells and Jane Addams. Du Bois was the only African American on the executive board of the NAACP at the outset. But the NAACP and Du Bois’s magazine, the Crisis, became the vehicle by which Du Bois’s brand of civil rights activism overtook that of Booker T. Washington, who died in 1915. The NAACP engaged in legal efforts to enfranchise blacks and to expose and punish lynching. They struggled to get anti-lynching legislation passed in Congress, however.

The NAACP scored its first Supreme Court victory in 1915 in the case of Guinn v. United States. In this ruling the court struck down an Oklahoma grandfather clause that exempted voters from literacy tests if their grandfather was eligible to vote. This functionally meant that many illiterate whites could still vote while illiterate blacks (or those deemed insufficiently literate) could not. The court ruled that the Oklahoma law violated the Fifteenth Amendment, which banned racial discrimination in voting rights. The ruling invalidated similar grandfather clauses that many southern states had adopted since the Civil War, but it left many legal and extralegal options in place for states to keep nonwhites from voting.

Political Reform in the States

Most political activity in the late 1800s and early 1900s still took place in states and towns, not at the national level. Some of the most fundamental changes of the Progressive Era came from outside of Washington, DC. Beginning in 1902, the state of Oregon passed a series of Populist-style reforms that became known nationwide as the “Oregon system.” These included the ballot initiative, which gave regular citizens the power to propose laws; the referendum, which gave voters the opportunity to vote on some new laws at the ballot box; and a recall provision, which made it possible for voters to remove politicians from office for corruption, incompetence, or other reasons. Oregon also instituted a system of direct primary elections, which allowed voters instead of political bosses to choose a party’s nominee for various offices. Oregon followed the example of several other western states when it gave women the right to vote in 1912, before the passage of national women’s suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, in 1920.

Oregon also led the way in changing the method by which Americans choose US senators. The Constitution had stipulated that state legislatures would choose a state’s US senators. That meant senators, unlike US representatives, were not directly accountable to the people’s votes. There were routine accusations about the problems this caused, including the introduction of corruption, favoritism, and bribery into the process of choosing senators. Oregon modified the system by requiring members of the state legislature to promise to support the winner of a party primary for US Senate, making the legislature’s role a mere formality. The House of Representatives began adopting constitutional amendments for the direct election of senators in the 1890s, but the Senate would not agree to it until 1912. The requisite number of states agreed, and direct election of senators was ratified as the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913. Whereas the framers of the Constitution had imagined the Senate would be somewhat detached from the people by the senators’ indirect election and six-year terms, the Seventeenth Amendment made the character of the Senate more like that of the House.

The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt

As the youngest president in American history, Theodore Roosevelt made a major impact on international and domestic policy. With his vision of the presidency as the “bully pulpit,” Roosevelt broke out of the mold of a string of relatively inactive or ineffective presidents since Reconstruction. He believed government should be a force for moral good, although it could never substitute for thriving families and other units of society that stood between the government and the individual. Roosevelt explained in a 1910 book that

the object of government is the welfare of the people. The material progress and prosperity of a nation are desirable chiefly so far as they lead to the moral and material welfare of all good citizens. Just in proportion as the average man and woman are honest, capable of sound judgment and high ideals, active in public affairs,—but, first of all, sound in their home life, and the father and mother of healthy children whom they bring up well,—just so far, and no farther, we may count our civilization a success. We must have—I believe we have already—a genuine and permanent moral awakening, without which no wisdom of legislation or administration really means anything; and, on the other hand, we must try to secure the social and economic legislation without which any improvement due to purely moral agitation is necessarily evanescent.

On race relations Roosevelt embraced Booker T. Washington as an advisor and even hosted him for dinner at the White House. Such a move was repulsive to much of the white southern press. A Memphis newspaper howled that Roosevelt had “committed a blunder that is worse than a crime, and no atonement or future act of his can remove the self-imprinted stigma. This is a white man’s country. . . . Race supremacy precludes social equality.” Likewise, a New Orleans newspaper took the dinner as a “studied insult to the South . . . forcing upon the country social customs which are utterly repugnant.” But Roosevelt’s overall record on race relations was complex, as he struggled to negotiate an alliance with white southern Republicans, many of whom (the “lily-white” Republicans) wanted to purge the party of black voters. Roosevelt, wishing to be seen as tough on black crime, dishonorably discharged hundreds of black soldiers because of an episode of racial violence in Brownsville, Texas, in 1906. Though there was little evidence and no trial, Roosevelt still concluded that the “Buffalo Soldiers” from Fort Brown were to blame. He discharged them without honor from the army. Booker T. Washington told the president it was a mistake, and W. E. B. Du Bois called the action a “sin.”

Still, Roosevelt was eager to use the power of the executive branch to bring about reform in areas that captured his attention. Prominent journalist Walter Lippmann wrote that Roosevelt was the “first president who realized clearly that national stability and social justice had to be sought deliberately. . . . He was the first president to grasp the fact that justice, opportunity, and prosperity were not assigned to Americans in perpetuity as the free gift of Providence.” Convinced that the federal government and its agencies could serve as forces for social good, Roosevelt and his immediate successors presided over a doubling of the number of federal employees.

Some of Roosevelt’s most celebrated actions came against the power of the trusts and big corporations. Courts had been reluctant to rigorously enforce measures such as the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890). Even though Roosevelt recognized that big business was the source of much innovation and employment, he also believed with his fellow Progressives that unchecked corporate power could threaten workers, small businesses, and the general welfare. He pressured Congress into creating a Department of Commerce and Labor, which used its investigative powers to expose some of the worst abuses of large corporations.

Roosevelt also prompted the Justice Department to challenge J. P. Morgan’s gargantuan railroad trust, the Northern Securities Company. Roosevelt contended that Morgan was failing to abide by the Sherman Antitrust Act and its prohibition on monopolies. In the case of Northern Securities Co. v. U.S. (1904), the Supreme Court narrowly ruled against Morgan’s corporation, mandating that it be broken up into several smaller companies. The Roosevelt administration initiated similar actions against monopolistic trusts in tobacco, chemicals, and meat production. His suit against John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil eventually led to its breakup as well in 1911. Roosevelt was not always as consistent as his “trust-busting” reputation might suggest, however. For example, in 1907 he permitted Morgan’s U.S. Steel to acquire a key steel competitor in the South, explaining that the move was critical to avert an economy-shaking collapse in that sector. Morgan also donated more than $100,000 to Roosevelt’s 1904 campaign.

At times Roosevelt also acted aggressively on behalf of workers, especially when he regarded big business as acting against the nation’s interests. The most celebrated instance came in Roosevelt’s extraordinary intervention in the United Mine Workers’ (UMW) 1902 coal strike in Pennsylvania. Coal-rich northeastern Pennsylvania supplied much of the fuel for heating in America, so this product had a direct bearing on life in many American homes. Irish-born socialist and UMW organizer “Mother” Mary Harris Jones described the plight of many of the mine workers, noting that many of the miners were recent arrivals from Europe. “Hours of work down under ground were cruelly long. Fourteen hours a day was not uncommon. . . . Families lived in company owned shacks that were not fit for their pigs. Children died by the hundreds due to the ignorance and poverty of their parents.”

The UMW represented many of the coal miners in Pennsylvania. When the union called for a wage increase and an eight-hour workday, the mine owners would not make concessions, believing that doing so would damage the industry and perhaps send the American economy into a tailspin. One hundred fifty thousand miners went on strike. The head of the mining companies, George Baer, saw the strikers as criminals and called for prayer that “right may triumph, always remembering that the Lord God Omnipotent still reigns, and that His reign is one of law and order.” As the strike dragged into late summer of 1902 and winter loomed, the price of heating coal quadrupled in some areas of the country.

Roosevelt summoned the head of the UMW and the mine owners to the White House, but the owners still refused to negotiate. The president was incensed, and he directed the secretary of war to begin preparations to go into northeastern Pennsylvania with federal troops and take over the mines. Even as he prepared for such drastic measures, however, he asked J. P. Morgan to intervene on the administration’s behalf. The threat of military intervention and the nationalization of the mines broke the mine owners’ resistance, and they agreed to federal arbitration of the dispute with the UMW. The miners also agreed, and they went back to the mines in October 1902. Lawyers for the UMW, including Clarence Darrow (who would become famous two decades later for his role in the Scopes Trial over teaching evolution) pointed to the monopolistic collusion between the mine owners, the railroads that controlled them, and financiers such as Morgan who lorded over the whole system. Those were the forces keeping wages artificially low, Darrow argued.

The federal commission eventually awarded some concessions to the workers, including wage increases and fewer hours. It declined to give the UMW official recognition as the miners’ representative, however. Although this did not give the UMW everything it had asked for, the outcome of the strike was a victory for organized labor and represented one of the first times the federal government had intervened on behalf of striking workers. As Roosevelt explained later, he expected that “big business give the people a square deal; in return we must insist that when any one engaged in big business honestly endeavors to do right he shall himself be given a square deal.” The concept of Roosevelt’s “square deal” meant the federal government should take an activist role in curtailing the worst abuses of major corporations, especially when those actions threatened to impact the daily lives of many Americans. Roosevelt’s philosophy was not hostile to business in general, but it positioned the federal government as police and arbiters in business and labor disputes.

Roosevelt’s desire to curb the excesses of big business also explains his interest in the conservation of natural areas and sustainable land development. Roosevelt did not agree with the philosophy of preservationists, who touted the value of leaving land pristine and untouched. He wanted land used for the benefit of the people but in a manner that was sustainable. Dating back to his brief, ill-fated time as a rancher in the Dakota Territory in the 1880s, Roosevelt also believed in the restorative value of being in nature. The frontier was a staple theme in his prolific writing career, including his popular four-volume The Winning of the West (1889–1896). He also felt that the government should restrain the uncontrolled development of lands by big business, which, left unchecked, could harm the long-term economic prospects of the nation because of the depletion of forests, mines, and other resources.

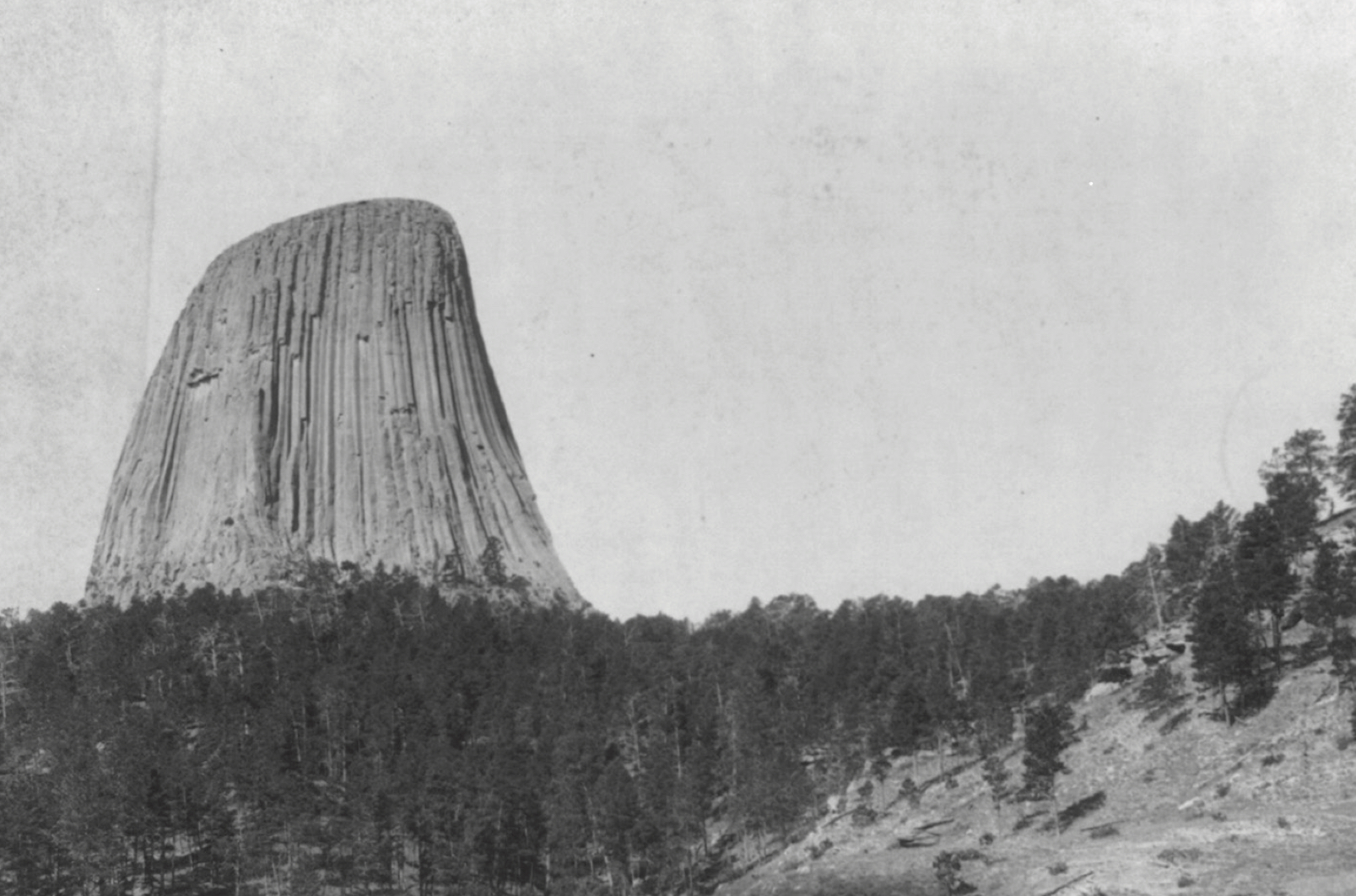

Roosevelt’s primary contribution to conservation as president was the creation of government preserves of land. The total amount of land in government-controlled preserves when Roosevelt became president was 45 million acres; by 1908, that number had swelled to 195 million acres. Much of that acreage protected forests, mining regions, and areas of special beauty or geological significance, such as the Grand Canyon in Arizona or Devil’s Tower in Wyoming. Roosevelt made Devil’s Tower the country’s first national monument in 1906. Much of the preserved land was in the West, where timber and mining companies and ranchers took a keen interest in the fate of acreage not yet used in their businesses. In 1907, Congress presented a bill that would prevent the president from adding any new national forests in the Northwest from Colorado to Washington State. Roosevelt signed the bill but not before creating or expanding thirty-two national forests, one of his most controversial moves. Western politicians were outraged, calling Roosevelt’s forests the “Midnight Reserves.”

The Taft Presidency

In the 1904 election Roosevelt trounced his Democratic opponent by two and a half million votes and more than doubling his rival’s total in the Electoral College. (The Socialist candidate Eugene Debs got no electoral votes but did receive 400,000 popular votes.) Having filled out most of President McKinley’s second term already, Roosevelt vowed not to seek reelection in 1908. His handpicked successor was his secretary of war, Ohio Republican William Howard Taft. In 1908, Taft easily defeated William Jennings Bryan, who was the Democratic nominee for the third time. But Taft’s comparatively laid-back approach offered an opportunity for latent factions among the Republicans to come to the surface. Most of his time in office, he struggled to contend with Republican infighting over tariff policy and the control of Congress.

Figure 19.5. Devil’s Tower. Devil’s Tower or Bear Lodge (Mato [i.e., Mateo] Tepee of the Indians), as seen from the east side. Located near the Belle Fourche River in Wyoming.

Nevertheless, Taft’s administration continued Roosevelt’s approach to extending American influence in the Caribbean, Central America, and East Asia. With a philosophy of “dollar diplomacy,” Taft argued that economic intervention was much preferable to using the military to get America’s way overseas. Thus, Taft got involved in debt crises in Honduras, Nicaragua, and Haiti. He also persuaded a group of bankers to help finance a major railway project in China, hoping to keep the Open Door policy alive in trade with the Chinese.

On the domestic front, among the signature achievements under Taft’s watch were the congressional passage of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Amendments to the Constitution, which authorized a federal income tax, and the direct election of US senators. Article I of the Constitution had prohibited Congress from passing “direct” taxes. An 1895 Supreme Court decision had ruled that an earlier income tax had violated that prohibition. In the nineteenth century the small federal government had largely relied on revenue sources such as trade duties and the sale of public lands. Tariffs continued to be a much-debated source of government funds, with opponents arguing that high tariffs impacted poorer people the most, partly because higher prices hurt those with the least money.

Progressives argued that it was only fair for those with the highest incomes to shoulder more of the tax burden. Opponents of the income tax and the Sixteenth Amendment worried that the government might eventually raise income tax rates to crippling levels. Some also contended that wealthier people should not have to pay higher percentages of their incomes in taxes—doing so was penalizing them just because of their wealth. Nevertheless, Congress passed the Sixteenth Amendment as a way to bolster government income in the face of lower tariff duties. The requisite number of states ratified the amendment by 1913, and Congress adopted a progressive system of tax rates, with gradually higher rates based on the amount of income people or companies earned. The issue of income tax rates has remained a perennial point of debate in American politics through the present day. Wartime rates have often gone particularly high, with the highest “marginal” tax rate on the top-earning Americans reaching an astounding 94 percent of income during World War II.

Disagreements with other Republicans kept dogging Taft’s administration, which inadvertently gave signals that it was trying to roll back parts of Roosevelt’s legacy. Most notably, Taft’s secretary of the interior, Richard Ballinger, engaged in an ugly feud with Gifford Pinchot, who had served as head of the forestry department under both Roosevelt and Taft. Ballinger sought to open up previously protected federal lands to miners and other businesses. Some Progressives suggested that Ballinger had a personal financial stake in opening these lands. Pinchot went public with his criticisms of Taft and Ballinger’s policies, and Taft subsequently fired him. Although Taft actually put a great deal of western land under federal protection and subsequent investigations exonerated Ballinger of the corruption charges, a public impression developed that Taft and Ballinger stood on the side of big business and against Roosevelt and Pinchot’s conservationist efforts.

The Return of Theodore Roosevelt and the Election of Woodrow Wilson

Progressive-leaning Republicans urged Roosevelt to consider another run for the White House. His frustration with Taft had pushed Roosevelt in an ever more Progressive direction, more so than when he was president. In 1910, he laid out a program of federal initiatives that Roosevelt labeled the “New Nationalism,” a philosophy that “regards the executive power as the steward of the public welfare,” Roosevelt explained. He advocated the kind of democratic reforms associated with the “Oregon system,” including the popular referendum and the option to recall elected officials. He also pushed for a progressive income tax, more aggressive regulation of large corporations, and protecting public lands from use by anyone but small-time settlers.

Roosevelt’s dissatisfaction with Taft and his continuing popularity in the nation made him a formidable challenger for the Republican nomination in 1912. Taft had secured the allegiance of many key Republican leaders in the states, however. Many states had not yet adopted the direct primary system, which tended to favor Roosevelt. So in mid-1912, the Republican Convention nominated Taft for reelection. The disgusted Roosevelt left the convention and decided to run a third-party campaign.

In August 1912, Roosevelt received the nomination of the Progressive Party, sometimes also called the “Bull Moose” Party (so named because during the campaign Roosevelt said that he felt as strong as a bull moose). As with the Progressive movement generally, the Progressive Party drew people from many sectors of American life, such as leaders from both the business world and labor unions. The Progressive Party was committed to women’s voting rights. Settlement house reformer Jane Addams seconded Roosevelt’s nomination for president, an unusually public political role for any woman yet in American history. Roosevelt’s campaign took on a revivalist tone as the candidate cast his platform as a matter of good versus evil by citing the apocalyptic battle of Revelation 16:

Here in this great republic it shall be proved from ocean to ocean that the people can rule themselves, and thus ruling can gain liberty for and do justice both to themselves and to others. We who stand for the cause of the uplift of humanity and the betterment of mankind are pledged to eternal war against wrong by the few or the many . . . fearless of the future; unheeding of our individual fates; with unflinching hearts and undimmed eyes; we stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord.1

Realizing that the divisions among the Republicans signaled their best chance for victory since Grover Cleveland in 1892, the Democrats nominated Woodrow Wilson, the governor of New Jersey. Wilson grew up in the Southern Presbyterian Church, and his father was a key church leader. Wilson’s deep sense of morality and the obligation to serve animated his work as the president of Princeton University and as the reform-minded New Jersey governor. In many ways the Democrats’ priorities in 1912 resembled those of the Progressives’: balancing the need for business growth with the need to protect workers and consumers. Although Wilson had lived and worked in New Jersey in the 1890s, he was steeped in the states-rights tradition of southern politics. Therefore, he was warier of top-down schemes led by the federal government than was Roosevelt.

In the general election of 1912, Wilson only won 42 percent of the popular vote, but he dominated Roosevelt and Taft with 82 percent of the electoral votes. Roosevelt and Taft had so divided the Republican Party that they gave a resounding victory to Wilson. The sitting president finished third and managed to gain only eight electoral votes. The Socialist Eugene Debs made his best showing yet, with almost a million votes, but this also cut into the support for the Progressive Party. The Democrats also won control of both houses of Congress, and Wilson understandably believed he had a broad mandate to govern.

In his inaugural address Wilson offered an explanation for the Democratic triumphs of 1912. “The Nation has been deeply stirred, stirred by a solemn passion, stirred by the knowledge of wrong, of ideals lost, of government too often debauched and made an instrument of evil,” he said. “The feelings with which we face this new age of right and opportunity sweep across our heartstrings like some air out of God’s own presence, where justice and mercy are reconciled.” Wilson laid out a political program he called the “New Freedom,” centered on lower tariffs, limitations on monopolistic trusts in business, and Progressive reforms in the nation’s financial systems. Wilson and the Democrats backed up the “New Freedom” with laws such as the 1913 Underwood-Simmons Tariff, which dramatically lowered the duties charged on imported goods. Wilson promised that this measure would lower consumer costs for everyone, but he also forecast that lowering the tariff would induce other countries to do likewise, opening global markets to more American products.

Figure 19.6. President Woodrow Wilson throwing out the first ball, opening day, 1916.

Reformers had called for change in the American banking system since a devastating financial panic in 1907 had nearly swamped tens of thousands of local banks. Although the idea of a national bank operated by the federal government had been controversial since Alexander Hamilton had first proposed one in the 1790s, advocates insisted that a central banking system could help stabilize the economy and avert crippling mass withdrawals from the banks in times of turmoil. They also argued that the central bank would reinforce the American currency, as it could boost or reduce the money supply according to current economic conditions.

William Jennings Bryan and other populist-leaning Democrats argued that consolidating the banking system would put even more power in the hands of elite financiers in New York City. These critics worried that the proposed Federal Reserve would really serve to protect the interests of big bankers rather than common people. Wilson encouraged lawmakers to establish a dozen regional branches of the central bank in an attempt to allay the concerns of the populists. With this adjustment made, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 to establish the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve sets the “prime” interest rate for loans charged to banks, which influences the interest rates for consumers who wish to borrow money to make purchases. The Federal Reserve Act was the most important domestic legislation of Wilson’s presidency, especially in terms of its enduring significance in American history. The Federal Reserve remains the chief governing unit of the banking system in the United States. The power and biases of the “Fed,” and its performance during periodic financial panics since 1913, has remained a topic of heated political debate.

Wilson was also inspired to take on the power of the trusts and financial elites by his advisor Louis Brandeis, who in 1916 would become the first Jewish member of the Supreme Court. In a series of muckraking articles that became the book Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It (1914), Brandeis warned of the unchecked power of America’s “financial oligarchy” who by “gradual encroachments” of power had taken over vast sectors of the economy and who exercised undue influence in the workings of government. “It was by processes such as these that Caesar Augustus became master of Rome,” he wrote. “The makers of our own Constitution had in mind like dangers to our political liberty when they provided so carefully for the separation of governmental powers.”

At Brandeis’s urging, Wilson and the Congress created the Federal Trade Commission, which possessed broad investigative power over “unfair methods of competition,” and the ability to give cease-and-desist orders to businesses violating antitrust laws. Brandeis was disappointed in the relative lack of enforcement power given to the Federal Trade Commission, however. The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 extended the anti-monopoly policies of the federal government too. Most important, from the unions’ perspective, it limited the courts’ ability to stop labor activists from striking.

Wilson was reluctant to embrace more radical aspects of the Progressive agenda. Many African Americans were discouraged by his administration’s record on race relations. The Democrats remained a heavily southern-oriented party, and the Republicans had traditionally counted on African American voters. But higher numbers of African Americans and civil rights activists had supported Wilson, who had courted them during the election of 1912. When Wilson became president, however, many of his cabinet appointees were white southerners who objected to integration in federal departments. Postmaster general Albert Burleson of Texas suggested that the departments begin the process of racial segregation of offices, bathrooms, and other facilities, and Wilson did not object. When leaders such as Booker T. Washington and Oswald Garrison Villard (the head of the NAACP) objected, Wilson informed them that segregation was “distinctly to the advantage of the colored people themselves” and that he believed many African Americans supported the policy. Wilson further explained that he did not believe there was any “discrimination along race lines but that there was a social line of cleavage which, unfortunately, corresponds with the racial line.” More aggressive protests against federal segregation did move the administration to curtail some of the most egregious examples of discrimination, but Wilson’s reputation among African Americans was damaged.

During his 1916 reelection campaign, Wilson instituted more labor reforms, such as a law providing compensation for injured federal workers, restrictions on child labor, and an eight-hour workday for railroad employees. These measures helped secure Progressives’ support for him, and he narrowly defeated the nominee of the reunified Republican Party in the 1916 election. But since the outbreak of World War I in Europe in 1914, the domestic priorities of the Progressives had started to fade in political importance. Campaigning on the slogans “America First” and “He Kept Us out of War,” the issues of the 1916 campaign increasingly centered on foreign affairs and the question of US intervention in World War I. In that sense the 1916 election marked the beginning of the end for the Progressive movement. Muckrakers and social reformers remained attentive to the excesses of American industry, but the eyes of most Americans focused on events in Europe.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bissett, Jim. Agrarian Socialism in America: Marx, Jefferson, and Jesus in the Oklahoma Countryside, 1904–1920. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999.

Chambers, John Whiteclay, II. The Tyranny of Change: America in the Progressive Era, 1900–1917. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1980.

Curcio, Vincent. Henry Ford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

García, Mario T. Desert Immigrants: The Mexicans of El Paso, 1880–1920. Repr. ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981.

Gerin-Gonzales, Camille. Mexican Workers and American Dreams: Immigration, Repatriation, and California Farm Labor, 1900–1939. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994.

Greenwald, Richard A. The Triangle Fire, The Protocols of Peace, and Industrial Democracy in Progressive Era New York. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005.

Hankins, Barry. Woodrow Wilson: Ruling Elder, Spiritual President. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Leonard, Thomas C. Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Repr. ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

McGerr, Michael E. A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920. New York: Free Press, 2003.

Painter, Nell Irvin. Standing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877–1919. New York: W. W. Norton, 1987.

1 “Progressive Covenant with the People,” audio recording, 3:21, https://www.loc.gov/item/99391565.