22

The Great Depression and the New Deal

The Great Depression was arguably the most crushing economic downturn in American history. Its devastating impact did more than ruin many family’s finances. It tore apart families themselves. Pauline Kael was a student at the University of California–Berkeley in the 1930s. She noticed how the Depression had left many students fatherless, both functionally and literally. Some fathers had left their families to seek work elsewhere. Some had permanently abandoned their wives and children, in part because of their distress and embarrassment over being unable to provide for them. Men who were once comfortably middle-class could not cope with the stress of abject poverty. Some even committed suicide, she recalled, with the despairing thought that at least their families could collect their life insurance.

At Berkeley, some of the students had nowhere to stay, so they slept under bridges on the campus. Even Kael, who had a scholarship to Berkeley, had to skip some meals due to her lack of money. She worked as a teacher’s assistant for seven courses per semester, which earned her fifty dollars a month. Stewing with economic and political resentment, Berkeley was becoming a “cauldron” for socialist and communist thought in that era. “You no sooner enrolled than you got an invitation from the Trotskyites and the Stalinists,” Kael remembered.

The Crash of 1929

It is easier to describe what happened in the financial disaster of late 1929 than to explain why it happened. Scholars ever since have disagreed about whether the government could have done more to avert, or at least to alleviate, the meltdown. Some of the problems at the root of the Depression were caused by the immense changes in the American economy since World War I. It is doubtful whether any Republican or Democratic administration could have designed policies that would have addressed all the economy’s structural weaknesses. The 1920s had seen enormous increases in consumer spending on goods such as automobiles and household appliances, but the huge increases masked deep fractures undermining the economy.

Many people, especially in the middle and upper classes, had put a great deal of money into the stock market. Although the market for consumer products had slowed down in the years before the crash, stock values continued to crest. Total share values on the New York Stock Exchange went from $27 billion in 1925 to $67 billion at the beginning of 1929. The number of active traders in the market (about 500,000 people) remained a small fraction of the American population, but the sales volume still surged from about 236 million trades in 1923 to more than 1.1 billion in 1928. Much of the stock was being sold on speculation. You only had to put a fraction of the dollar value down to buy stocks on the assumption that the value would continue to soar and you could make a killing without needing much money up front. Banks similarly engaged in dangerous lending practices. The economy was becoming a house of cards, precariously built on risky credit and rising stock prices. But few realized the risks. The Wall Street Journal issued an infamous forecast in August 1929 that “the outlook for the fall months seems brighter than at any time in recent years.”

Instability shook the stock market in September, and then in late October the house of cards collapsed. Top stocks such as the Radio Corporation of America and Westinghouse dropped by half almost instantly. By mid-November the market’s industrial sector overall had shed half of its stock value compared to September. Some expected speculators to return and boost the market once again, but the stomach-churning decline continued for years. The department store and mail-order company Montgomery Ward, for example, eventually saw its stock price drop from a high of $138 to just $4.

The Great Depression

The market crash began a crippling spiral of economic contraction that lasted for years. Banks that survived had to cut back on their lending. Reducing the amount of lending meant less spending by consumers on everything from homes to entertainment. Reduced spending meant that factories and service providers had to cut back on their operations, and they laid off many workers and cut the wages and hours of others. That led to further reductions in consumer spending, and the vicious cycle continued. America’s gross national product (the value of the total amount of goods and services produced) fell by two-thirds. Steel and auto plants were often operating at 20 percent of capacity, or even less.

Unemployment shot up to 25 percent by 1932. In some towns, especially in the industrial Midwest, unemployment was much higher. Half of the working-age population of Cleveland, Ohio, was unemployed. In Toledo unemployment hit 80 percent. African American unemployment in the cities was twice the rate of whites, as factories tended to lay them off first. Desperate unemployed whites became more willing to take what had traditionally been seen as “Negro jobs,” such as being household servants or garbage collectors. Conditions were even worse for poor black and white laborers in the rural South. The flow of African Americans to the urban North continued during the Depression in spite of the lack of ready work there.

In the Southwest the Depression reversed the flow of Mexican immigration into the United States. By 1930, some 1.5 million Mexican immigrants lived in the United States, mostly in states from California to Texas. Mexico (like many other nations) was also hit hard by the Depression, so returning there offered no particular economic advantage for these immigrants. Frustration over the economic suffering encouraged another wave of anti-immigrant backlash, however. Like blacks, Mexicans were often the first to lose their jobs. Even before the stock market crash, Congress passed the Deportation Act (1929), which gave local authorities enhanced powers to expel Mexicans and other immigrants. As the hardships of the Great Depression deepened, many argued that the country could not afford to provide immigrants with social services and welfare benefits. Between 1929 and 1939, some 1 million Mexicans and Mexican Americans were deported from the United States. Perhaps another million left because of duress caused by unemployment and the denial of social services. Many of those who left or were forced out were US citizens or could have claimed US citizenship. Immigration officials routinely engaged in Hispanic roundups. If those suspected of being Mexican could not produce proof of residency, they were sent to Mexico. Four hundred worshippers at Los Angeles’s La Placita Church were detained and deported as they left Catholic mass one Sunday in 1931.

Many Jews, Catholics, and Protestants sought to expand their traditional efforts to minister to the poor during the Great Depression. Abyssinian Baptist Church, the largest church in Harlem and one of the largest Protestant churches in the country, had for years provided services to the poor and the elderly in its largely African American community. But when the Great Depression struck, Pastor Adam Clayton Powell Sr. insisted that the church needed to do more. Citing a phrase from Jesus in the Gospels, Powell warned, “The axe is laid at the root of the tree and this unemployed mass of black men, led by a hungry God, will come to the Negro churches looking for fruit and finding none, will say cut it down and cast it into the fire.” Powell said he was committing a third of his annual salary to help those suffering. Emotional congregants responded with generosity, and the church increased its programs to give home heating fuel, food, and clothing to the poor. During 1930–1931 alone, Abyssinian Baptist assisted more than 40,000 people. Even heroic efforts like these, however, could not keep pace with the crushing burdens of the Depression.

Farmers and the Dust Bowl

Urban dwellers were not the only ones to endure the ravages of the Depression. Poverty and want were perhaps most pervasive among the farming and sharecropping people of rural America. Farmers’ income in America dropped by two-thirds between 1929 and 1932. Reporter Lorena Hickok toured rural areas during the mid-1930s and was stunned by what she saw. In the South she observed starving blacks and whites who would “struggle in competition for less to eat than my dog gets at home, for the privilege of living in huts that are infinitely less comfortable than his kennel.” The Depression took its toll on such sharecroppers and farmers, of course, but the economic collapse was also just perpetuating problems that dated back to the era of slavery.

The statistics of the era reveal deep patterns of poverty and a lack of education and sanitary facilities for many Americans. In 1934, the average annual income per person in farming families across America was a mere $167. Only a tenth of farmhouses had an indoor toilet; “outhouses” remained the standard. Only a fifth of farmhouses had electricity. Many rural Americans suffered from ailments related to malnutrition that doctors could have easily cured if doctors were available. In more than 1,300 counties in rural regions, there was not a single hospital. In rural America almost a million children between the ages of seven and thirteen were not attending school. Older children attended school even less frequently.

The climate and overworked soils across much of the Southwest and Great Plains only exacerbated the economic trials of the 1930s. For the first half of the decade, those regions endured the “Dust Bowl,” a prolonged drought that wrecked the fields and livelihoods of countless farming families. The 1920s had seen more and more intensive farming, which left topsoil more vulnerable to drought and erosion. When the rains stopped, the soil became bone-dry and powdery, and winds swept it away in massive dust storms. John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939) immortalized the experience of the Joad family of Oklahoma and the “Okies’” great out-migration to California. But farmers from Colorado, Kansas, Texas, and Arkansas also had to leave, often with virtually no possessions, to find work elsewhere—usually in California.

The Dust Bowl migration gave California’s culture a new dose of southern character. The parents of the great country singer Merle Haggard, for example, left Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl and moved to Bakersfield, California. In 1937, Haggard was born in a train boxcar the Haggards had converted into a home. The Dust Bowl and the migration west remained a staple theme of Haggard’s music. He was probably best known for his 1969 hit “Okie from Muskogee,” which extolled the simple values of small-town America.

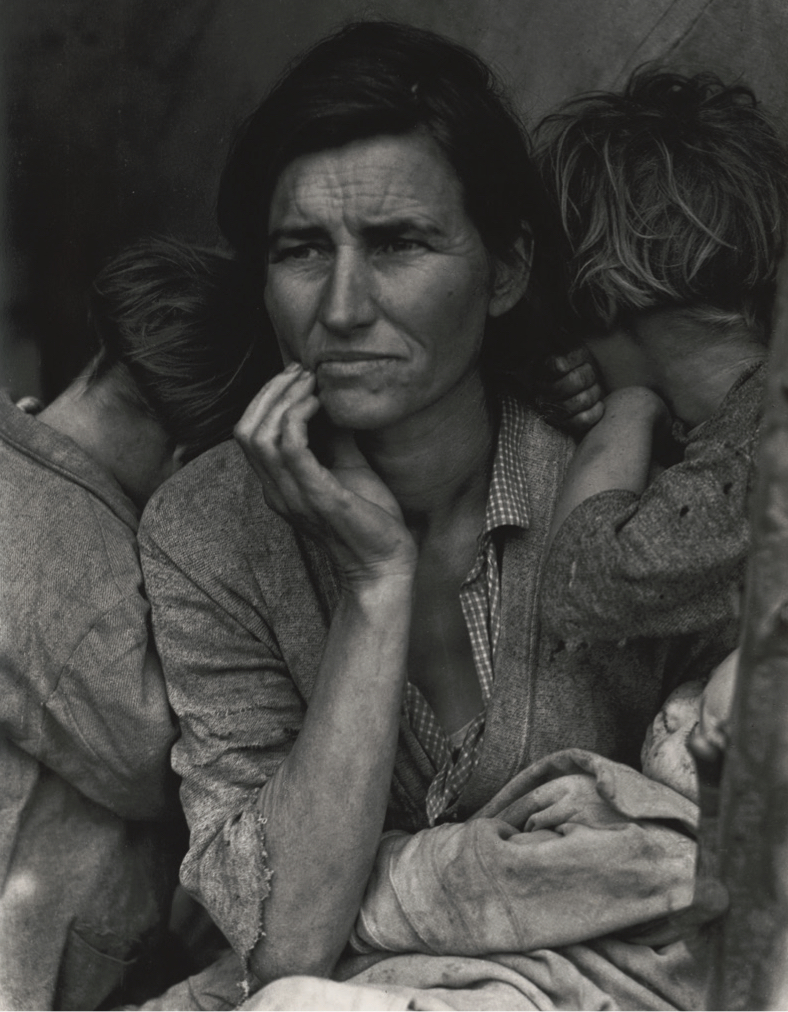

Figure 22.1. Migrant Mother. Iconic Dorothea Lange photo of a thirty-year-old California pea picker and mother of seven. February 1936.

The Political Response to the Depression

President Herbert Hoover has gained a somewhat unfair reputation as having done nothing to avert the economic collapse of the Depression. That criticism presumes that the national government could have enacted a better plan than Hoover’s to stave off or at least alleviate the worst of the Depression. That it could have done so is highly doubtful since the nation really did not emerge from the Depression until World War II, well into Franklin Roosevelt’s long presidency. Hoover did act against the Depression, although he preferred to leave jobs and relief in the hands of businesses and private agencies rather than the government. Even so, Hoover ramped up federal construction programs to create more jobs and signed major legislation establishing farmers’ cooperatives to help stabilize agricultural markets. He also encouraged the creation of the National Credit Corporation, which was designed to keep small banks afloat. He pleaded with businesses not to lay off more workers and to maintain a basic minimum wage for employees. Drawing on his experience in coordinating relief efforts in post–World War I Europe, Hoover helped coordinate private agencies’ assistance to the poor and unemployed. He also implored local governments to take care of their own people. But Hoover was reluctant to get the national government involved in direct handouts of assistance, believing that would only worsen the economic malaise, escalate the national debt, and create a culture of dependence on government assistance that would prove hard to break.

Figure 22.2. Dust is too much for this farmer’s son in Cimarron County, Oklahoma.

Hoover’s modest federal initiatives, combined with private charity and local government assistance, did not do much to curtail the terrible crisis. States and cities found themselves swamped with new requests for public assistance, even as declining tax revenues made sustaining relief at their current levels difficult. By 1932, many cities had completely run out of funds to help the newly unemployed or destitute. Some cities, such as Dallas and Houston, cut corners by giving assistance only to white families, not to Mexicans or African Americans. Whether it was fair or not, Hoover took the blame for the Depression—he was the nation’s political figurehead, and he was president when the crash happened. His name became a term of derision for many Americans. Across the nation shantytowns called “Hoovervilles” sprang up. Migrants and the homeless living in Hoovervilles “squatted” on public lands, erecting tiny shacks with scrap and discarded materials.

The Depression and Radical Unrest

Given the grotesque deprivations of the Depression, it is no surprise that signs of unrest and radicalism appeared across the nation such as at Pauline Kael’s University of California. People across the socioeconomic spectrum began to consider socialism, Marxism, and even Soviet-style communism. After reading Karl Marx’s work, novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote that “to bring on the revolution, it may be necessary to work inside the communist party.” Communist operatives gained a hearing in seemingly improbable areas, such as in parts of the Deep South. The Bethel Baptist Church, in a predominantly African American neighborhood in Birmingham, Alabama, was riven by terrible controversies over communism. Several members in the early 1930s were communist activists, but the pastor, Milton Sears, was vehemently anti-communist. When the pastor helped police find an accused black suspect in a criminal investigation in 1933, Sears drew the ire of many of the city’s African Americans as well as Communist Party activists. Communists passed out a brochure calling Sears a “preacher for the Lord, spy for the police, and framer-up of workers.” When a communist-led crowd confronted Sears during a service, the pastor pulled out a shotgun and drove his antagonists from the sanctuary. (Two decades later Bethel Baptist was the church of pastor and renowned civil rights activist Fred Shuttlesworth.)

Figure 22.3. Home of Mexican squatters in San Antonio, Texas, made of scrap and discarded materials. Photograph by Russell Lee, March 1939.

In San Francisco frustrated longshoremen and dock workers shut down the city’s port for two months in 1934. When business leaders finally sent in substitute workers to try to break the strike in July, longshoremen attacked them with rocks and iron pipes. Police accompanying the strikebreakers struck back, opening fire on the dock workers and flooding the streets with tear gas. The police dispersed the workers, but two of the strikers were killed in the clash. Harry Bridges, the openly communist head of the International Longshoremen’s Association, called for a general strike in the city in response to the killings; 130,000 workers responded, representing a wide range of trades. Virtually all business in the whole city of San Francisco came to a halt until feuding between rival unions resulted in a resumption of work and negotiations for better working conditions also resumed.

The incident that best illustrated the breakdown of the relationship between many of the American people and the Hoover administration was the federal crackdown on the “Bonus Army” of veterans in Washington, DC, in 1932. Tens of thousands of out-of-work World War I veterans had descended on Washington in the spring of 1932 to demand early payment of a cash “bonus” that Congress had authorized to be paid to them. The bonus was not due until 1945, but the veterans argued that given the dire conditions, Congress should issue the payments early. Congress declined. Many of the Bonus Army’s members left the capital city, but a few thousand stayed in Washington. District police tried to remove them from their encampment in July, but some of the veterans refused to budge. In the ensuing violence two of the protestors were shot and killed.

Figure 22.4. Bonus Army marching to the US Capitol; the Washington Monument is in the background, July 5, 1932.

President Hoover summoned federal soldiers to assist the police confronting the Bonus Army. Tanks and infantrymen went in, led by Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur, who would later become famous for his roles in World War II and the Korean War. (MacArthur’s assistants in 1932 included future World War II generals George S. Patton and Dwight D. Eisenhower, who would also become US president in 1953.) MacArthur’s forces used tear gas to evict the marchers from their camp, and then they burned down the protestors’ ramshackle tent village. MacArthur’s tactics had clearly exceeded Hoover’s intentions, yet Hoover did not discipline him. MacArthur regarded the marchers as a “mob . . . animated by the essence of revolution” who threatened the stability of the federal government. The image of the administration turning the force of government against impoverished veterans was one of the last, and worst, public relations disasters for President Hoover.

The Election of 1932

Republicans reluctantly renominated Hoover to run for president in 1932. It is hard to imagine a candidate having less of a chance of winning. Unless the Democrats had committed some stupendous mistake, they were virtually guaranteed to recapture the White House for the first time since Woodrow Wilson. The Democrats committed no such mistake, wisely nominating the experienced and savvy New York governor Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) to run against Hoover. Roosevelt was from a wealthy New York family and was a distant cousin of former president Theodore Roosevelt, who had died in 1919. FDR had lost the ability to walk without assistance because of a bout with polio in 1921. His own struggles may have helped him identify with those of regular American people in spite of his elite background. Roosevelt had a clear, confident style of communication that worked superbly in the new radio era, and he was eager to employ new communication methods as a candidate and as president.

When he accepted the Democratic nomination in Chicago, Roosevelt immediately began speaking of how he would make a “new deal” with the American people. After several years of the Depression, it was a message the majority of American voters were eager to hear. In 1928, the New Yorker Al Smith had been unable to unify the Democrats’ traditional constituencies in the urban North and rural white South. Roosevelt put those constituencies back together again. Outside of winning a few northeastern states, Hoover lost badly in the Electoral College. Roosevelt won by a margin of 472 votes to Hoover’s 59, and Roosevelt won a clean sweep in the states of the Midwest, West, and South.

Roosevelt Confronts the Depression

The crisis of the Depression showed little sign of improving when FDR took office. A quarter of the American workforce remained unemployed, and states were routinely declaring “bank holidays” to keep their financial institutions from collapsing. Roosevelt himself had narrowly avoided being assassinated even before he took office (the assassin’s bullet did take the life of the mayor of Chicago). In his first inaugural address, which was filled with biblical allusions, Roosevelt set a decisive but reassuring tone for his presidency. “This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper,” Roosevelt declared. “So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Insisting that the time had come for aggressive national action against the ravages of the Depression, FDR indicated that he would ask Congress for “broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

One of FDR’s biblical allusions in the first inaugural was to the “unscrupulous money changers” in the financial sector who sacrificed the public good for personal gain. His first move as president was to secure the passage of the Emergency Banking Act, which sought to keep the banks solvent after a short national banking holiday. Congress hastily passed the law before some of its newest members had even settled in. FDR used the first of his “fireside chats,” delivered in national radio addresses, to assure Americans that they could safely leave their money deposited in banks. His assurances worked: the flood of withdrawals slowed when the banks reopened. Congress and the president followed up with other regulations that prohibited risky speculation by financial institutions, and they created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which protected people’s bank deposits from catastrophic losses.

Although FDR would soon authorize huge increases in federal spending under the “New Deal,” his early inclination was to cut spending and to generate new sources of revenue for the government. Remarkably, FDR was able to get a coalition of Republicans and Democrats to agree to cut payments to veterans, exactly the issue that had prompted the crisis of the Bonus Army late in Hoover’s presidency. But FDR was riding a wave of popularity that allowed him to do it, and Congress cleverly paired the budget cuts with the beginning of the end of Prohibition. Congress had passed an amendment repealing Prohibition before Roosevelt took office, based on the belief that the banning of alcohol had been a failure and that taxing the sale of alcohol represented an appealing source of government income. The required number of states had ratified the Prohibition repeal by the end of 1933, and it became the twenty-first amendment to the Constitution. In anticipation of that amendment, Roosevelt signed the Beer-Wine Revenue Act within two weeks of taking office, legalizing the sale and taxation of beer and wine in America.

The Hundred Days

With these early measures out of the way, FDR’s administration and Congress entered upon the “Hundred Days.” Whatever critics thought of their propriety and success, the legislation passed during the Hundred Days was the quickest and most transformative set of laws ever at the outset of an American presidency. During these months FDR put fifteen major requests before Congress, and Congress returned fifteen laws to him for signature. Some of them created institutional legacies that have persisted through the present day in America. These programs reflected the opposite of Hoover’s hope that relief could be handled privately or by the states. Although states were given increased recovery funds under the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Congress and the president created a dizzying array of agencies and federal employers that gave the New Deal a distinctly top-down, centralized tone. There were so many new abbreviated agencies such as FERA, TVA, CCC, and WPA that critics like former presidential candidate Al Smith said the national government was “submerged in a bowl of alphabet soup.”

The concept behind work programs like the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was to put people to work doing public jobs that would have lasting benefits but that employees of private businesses were unlikely to perform. The TVA took on the gargantuan challenge of bringing electrification and flood control to a large swath of Appalachia. It transformed the landscape of this region, centered on East Tennessee but extending to parts of seven states, by building hydroelectric dams and creating new lakes. The CCC, Roosevelt’s favorite, sent workers across the nation to engage in conservation projects in America’s national parks and national forests. It would eventually give work to almost 3 million people. CCC workers built countless trails, small dams, bridges, and miles of fencing and terracing. The CCC was eliminated in 1942 in the midst of the demands of World War II. But in the intervening years, they had left traces and structures that remain visible today in parks from coast to coast.

A man named Blackie Gold, who went on to become a car dealer with a comfortable middle-class life, experienced the depths of the Depression personally before enlisting in the CCC. His father died when Gold was an infant, and he and his siblings had to beg for heating coal. His mother could not afford to take care of Gold any longer, so she placed him in an orphanage where he stayed until he was seventeen. He joined the CCC in 1937. Gold traveled the country with the CCC, planting trees in Michigan and fighting forest fires in Idaho. The CCC provided for his basic needs, including three meals a day. “They sure made a man out of ya,” he said, “because you learned that everybody here was equal.” Gold thought this belief extended even to race relations. (The CCC usually operated in segregated units, but it did employ African Americans and Mexican Americans and paid them the same as whites.) “We never had any race riots,” Gold recalled. There were a “couple of colored guys there, they minded their business; we minded ours.” Black CCC workers did encounter overt hostility at some camps, however. Local white residents near Tennessee’s Shiloh National Military Park, which was hosting a team of African American laborers, asked that the workers be removed because “ours is not a negro community and we do not know how to handle them.”

New Deal Bureaucracy

Agencies like the CCC remained helpful and popular, but some units of the New Deal struggled to fulfill their intended functions. The National Recovery Administration (NRA), for instance, represented a vast national effort to coordinate industry and labor leaders into a system of pricing, hours, and production limits. NRA leaders hoped they could stabilize American businesses and ensure both profitability for industry and fair treatment for workers. In reality the NRA turned into an enormous bureaucratic mess. Compliance was voluntary, and many business leaders became convinced that America’s most powerful companies were dictating the NRA’s codes and regulations to their benefit. Workers also felt that the regulations were tipped in favor of business over labor. The NRA drowned in a sea of regulatory complexity, with thousands of NRA desk workers creating intricate codes for American businesses. Even obscure industries faced mountains of regulations: corkmakers alone operated under thirty-four sets of codes, each with its own lists of regulations. Within two years the NRA had produced codes that filled 13,000 pages with their rules. Critics said the NRA really stood for “No Recovery Allowed.” Journalist Walter Lippmann observed that because of top-down efforts like the NRA, the “excessive centralization and the dictatorial spirit are producing a revulsion of feeling against bureaucratic control of American economic life.”

Figure 22.5. CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) workers putting up a fence. Greene County, Georgia, 1941.

In the 1935 case Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that many of the NRA’s activities were unconstitutional. The Schechter company was a kosher poultry seller in Brooklyn that had been charged with a number of violations of NRA regulations, including selling “unfit chickens.” The Supreme Court agreed that the rules, and the law enabling them, exceeded both the president’s and Congress’s powers to regulate local commerce. According to the Tenth Amendment, the court contended, such regulatory powers should be left to the states. Schechter was one of the first judicial roadblocks President Roosevelt faced in the implementation of his New Deal programs.

Roosevelt made similar centralizing efforts in farming with the creation of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). In farming a classic problem was that farmers always brought as much produce and meat to market as they could, though doing so reduced prices and profits for all farmers. By using subsidies, the AAA encouraged farmers to cut production, taking acreage out of use and in some cases even plowing under crops such as cotton and killing piglets so they would not become the bacon and pork of tomorrow. (Critics worried about the morality of such “pig infanticide” when millions of Americans did not have enough to eat anyway.) In the short term such tactics did help raise farm prices and revenue overall. The Dust Bowl ironically was one of the biggest aids to the AAA because the forces of drought and wind took so much land out of production involuntarily.

Like the NRA’s programs the AAA often benefited big agricultural companies and independent farmers and left poor farm workers and sharecroppers out. Owners were theoretically supposed to share the proceeds of their subsidies with workers, but in practice that often did not happen. Mexican workers were some of the most vulnerable, especially if they were recent arrivals to the United States or spoke little English. On Colorado’s sugar beet farms, which were the largest beneficiaries of the state’s AAA payments, farmers took so much acreage out of use that many Mexican workers were left without work. Unemployed Mexicans in Colorado and elsewhere were often specifically prohibited from receiving state or local relief funds, and they found it difficult to get approved for federal relief as well. In one Colorado county individual beet farm workers earned an average of seventy-eight dollars per year.

Perhaps the most important legacy of the AAA is that it put major farming sectors under the authority of the federal government. The government has continued to provide subsidies to keep crops and meats affordable, but the subsidies affect only certain kinds of grains and grain-fed meats. Historically, farmers who grow cotton, sugar, wheat, and soybeans have received the bulk of US agricultural subsidies, while fruit and vegetable farmers have been left out. Regardless of the relative nutritional merit of sugar and grains, they have remained cheap and have become ever more central to the American diet. Sugar and grains are especially common in processed and packaged foods.

Disparities in the recipients of farm subsidies have also persisted. Again big farming companies have been more likely to receive government payments than small family farmers. Large farming operations in the Midwest and Great Plains regions receive the bulk of the payments. Other farmers, whether large or small, in fruit- and vegetable-producing states such as Michigan, California, and Florida receive few subsidies. Since the creation of the AAA, Congress has been responsible for passing major farm bills every five years or so, but reform of the subsidies system has proven elusive.

Critics of the New Deal

The New Deal was massive and ambitious. By the end of FDR’s first term in office, the federal budget deficit had grown to $4.5 billion, 55 percent larger than when he became president. The total federal debt had also more than doubled since the time of Hoover. Yet many of the Depression’s problems had hardly budged. FDR’s policies inevitably drew out critics from across the political spectrum. Some socialists and communists welcomed the New Deal, while others thought it did not go far enough to rein in businesses. Many conservative Protestants echoed concerns like those voiced by Walter Lippmann about the consequences of government central control. Some even speculated that the New Deal was a precursor or a “rehearsal” for the evil one-world government headed by the Antichrist in the last days. Some fundamentalists suggested that the ubiquitous Blue Eagle symbol of the National Recovery Administration was a forerunner to the Antichrist’s “mark of the beast.” One fundamentalist writer conceded that the Roosevelt administration was well-intentioned in its desire to alleviate Americans’ suffering during the Depression but said that the New Deal was “preparing people for what is coming later . . . the big dictator, the superman, the lawless one.”

Detroit-based Catholic priest Charles Coughlin was one of America’s pioneers in using radio to spread a religious-political message. Originally an FDR supporter, Coughlin eventually used his vast radio platform of perhaps 40 million listeners to criticize the New Deal for not going far enough. Coughlin blamed “predatory capitalists” for much of America’s financial woes. FDR should have broken the power of the bankers and redistributed income in a just manner, Coughlin insisted. Calling FDR “Franklin Double-Crossing Roosevelt,” Coughlin accused him of being a faithless politician who had “promised to drive the money changers from the temple, [but] had succeeded in driving the farmers from their homesteads and the citizens from their homes in the cities.” By the late 1930s, Coughlin’s views had become progressively exotic, conspiratorial, and anti-Semitic (anti-Jewish). He spoke positively about the rise of Nazism in Germany and suggested that Jews and communists controlled the American government and economy. Once America entered World War II, the threat of arrest for sedition by the Roosevelt administration finally silenced Coughlin.

Another key Catholic figure of the era, Dorothy Day of the Catholic Worker Movement, was more reserved in her criticisms of FDR, focusing more on ministering to the poor themselves. Day had become a socialist in the 1910s, but in the late 1920s she converted to Catholicism. Day and French priest Peter Maurin founded the journal the Catholic Worker in 1933. The Catholic Worker advocated for pacifism and Catholic socialism and reached a circulation of 150,000 by 1936. Day renewed the older tradition of settlement houses in impoverished districts of New York and other American cities. She certainly preferred FDR to the Republican presidents of the 1920s, but she also thought FDR delivered too little on his promises to the workers and farmers. They saw him as a “savior,” she said. “The problem was . . . he wasn’t their savior. His policies were an emergency response to a situation that threatened the country’s stability. By the end of the 1930s the same problems were there, as serious as ever.” Day went on later to protest America’s roles in foreign wars and its nuclear armament buildup in the 1950s. In the 1960s, she became a vocal supporter of César Chávez’s United Farm Workers of America movement in solidarity with Mexican migrant laborers.

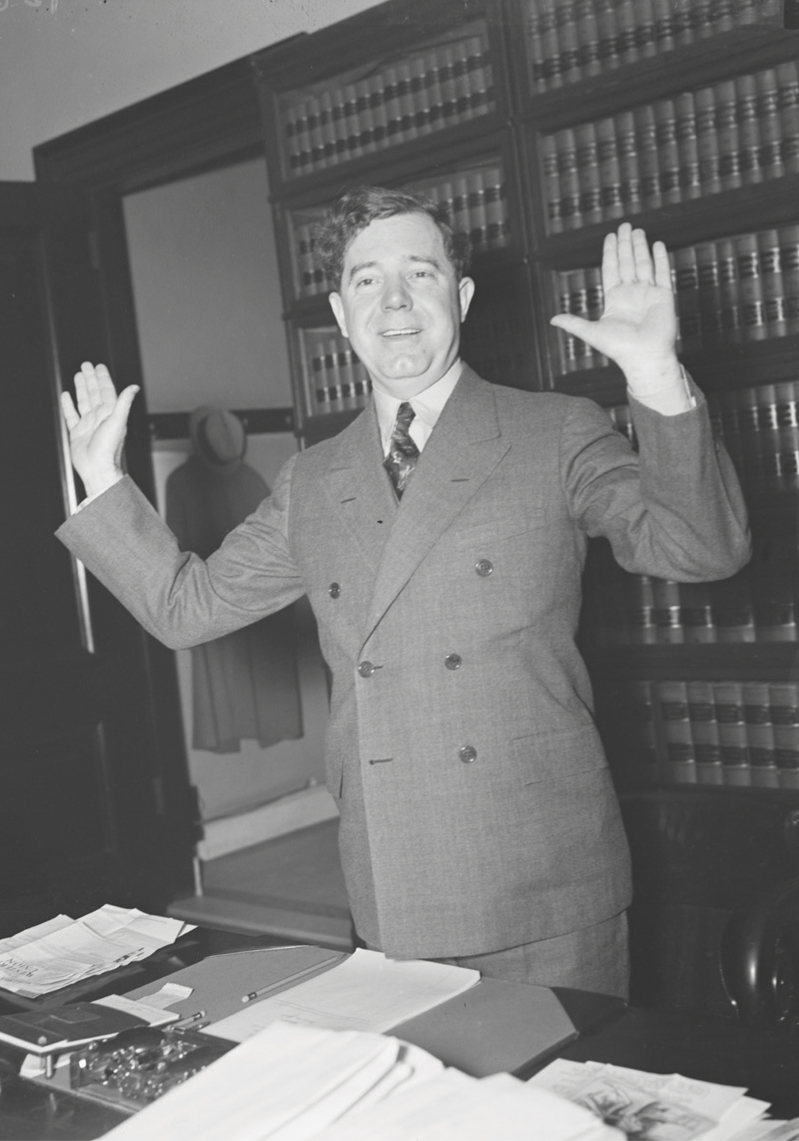

The most flamboyant critic of the New Deal was undoubtedly Huey P. Long, governor and senator from Louisiana. Long helped resurrect the populist tradition as the answer to his state’s woes during the Depression. Long was elected governor in 1928, running on a platform of opposition to elite financial interests before the Depression even began. (Like many southern states Louisiana still struggled with disproportionate poverty levels that dated back to Reconstruction.) Like his ally Father Coughlin, Long originally supported FDR but came to believe the New Deal was unduly favorable to big business. FDR, for his part, scoffed at Long’s “crackpot” ideas. In 1934, Long began to eye his own presidential run as he launched his “Share Our Wealth” program, which was based on high taxes for the rich and for business sectors such as the oil industry. Long envisioned massive redistribution of wealth and huge investments in public projects from roads to the facilities of Louisiana State University. He also called for a guaranteed minimum income for all people to maintain a basic standard of living for everyone. Long also built a ruthless and corrupt political machine, requiring payoffs from any person or business who wished to remain in good standing in the state. Long generated an enormous debt for the Louisiana state government. Even so, Long remained enormously popular in Louisiana when he was killed by an assassin in 1935.

The Second Hundred Days and Social Security

Mindful of critics like Long and Coughlin, and realizing that the effects of the Depression remained debilitating, FDR launched a new legislative program in 1935 that some call the “Second Hundred Days.” Congress raised taxes on businesses and the wealthy, with the top income tax rate reaching 79 percent. Much of the new spending was reflected in the Emergency Relief Appropriation Bill, or what FDR called the “Big Bill.” This spending measure cost $5 billion, which by itself was greater than the entire federal budget in the last year of the Hoover administration. The Big Bill gave new funding to agencies such as the Civilian Conservation Corps, but it also created the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which would eventually employ more than 8 million Americans.

Figure 22.6. Huey P. Long.

Critics noted that WPA funds became tools of local Democratic machines and party bosses. Nonwhites often suffered discrimination from local WPA agents. But for millions who had few employment prospects, the WPA supplied work for people building roads and bridges. Workers from the CCC and the WPA helped construct the iconic Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina and Virginia. At the behest of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the WPA also employed many out-of-work artists, musicians, and writers. One of the most valuable results of the Federal Writers’ Project of the WPA was an incomparable collection of thousands of interviews with former slaves. Although the interviews reflect biases of the WPA employees, the project produced 10,000 pages of recollections of life in the South that otherwise would surely have vanished from history’s written records.

The New Deal program with the broadest lasting significance was the Social Security Act of 1935. FDR entrusted the design of this program to Frances Perkins, who as the secretary of labor was the first woman ever appointed to head a presidential cabinet office. Perkins was a disciple of the settlement house reformer Jane Addams. In 1911, she had led an official New York state investigation into the horrific Triangle Factory fire, which had resulted in the deaths of 146 women workers. This had secured her commitment to Progressive principles and labor reform.

Until the Social Security Act, the nation had little in the way of old-age pensions or of unemployment or disability insurance. Although the Constitution spoke of serving the “general welfare,” what contemporary Americans think of as “welfare” programs were limited as of the early 1930s outside of pensions given to military veterans and their dependents. “Retirement” was not really an option for most workers. If Americans got too sick or feeble to work, the best option for many was depending on the help of adult children or other family members. The influential physician and reformer Francis Townshend had proposed that the government should start providing guaranteed old-age pensions of $200 per month. FDR thought the administration should consider a “cradle to grave” system of insurance and benefits so no one would become destitute because of a job loss, an injury, or old age. But any old-age program this comprehensive would be phenomenally expensive, and there was much pressure to leave pension and insurance plans in the hands of the states. So Perkins and other presidential advisors sought to craft an economically and politically feasible plan.

Figure 22.7. Mrs. Mary Crane, 82-year-old ex-slave, Mitchell, Indiana, between 1937 and 1938.

In the end the Social Security Act left the planning and distribution of unemployment and disability insurance mostly to the states. The administration originally imagined that the act might take on the enormous burden of health insurance too, but the final version effectively abandoned that issue. Government health insurance for the poor and elderly would wait another three decades until the advent of Medicaid and Medicare. The major part of the act that fell under direct federal supervision was the old-age pension system (a system that has become synonymous with the name “Social Security”). Americans would be required to make “contributions” to the old-age pension system. In fact, these were taxes on individuals, forcing them to contribute to the system. Social Security would theoretically provide a minimum income for them when they reached old age.

Critics noted that the burden of Social Security taxes fell hardest on poor Americans. But many of the poorest Americans, including farm workers and domestic servants, were explicitly excluded from coverage under the old-age pension plan. Disproportionate numbers of these workers were African Americans, leading the NAACP to comment that Social Security was like a “sieve with the holes just big enough for the majority of Negroes to fall through.” Amendments including the unrepresented workers were not adopted until the 1950s. Some of those workers who were not included did not object, however, because it meant they did not have to make compulsory contributions to Social Security. FDR realized that making the Social Security fund partly dependent on individual contributions would likely secure Social Security’s existence indefinitely. Once having paid into the system, workers became insistent (whatever their political preferences) that they get their fair share back when they retired. In 1940, a seventy-six-year-old Vermont woman received the first Social Security old-age support check. It was for $41.30. With annual payments today totaling in the hundreds of billions of dollars, Social Security (with its related health insurance programs added in the 1960s) went on to become the biggest expenditure in the federal budget.

Organized Labor and the New Deal

The Depression saw a revitalization of the labor movement in America. Depression-era workers (those who were able to maintain employment) felt the pinch of declining wages. They often saw themselves as having collective interests that were at odds with business owners. But unions had declined in importance during the 1920s, and in certain sectors, including automobiles and steel, union organizing was largely absent. The 1935 Wagner Act, or National Labor Relations Act, gave new life to the unions. It gave workers stronger access to collective bargaining with their employers and created the National Labor Relations Board, which was tasked with enforcing the law and policing anti-union tactics by businesses.

Leaders of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) were not interested in trying to organize assembly-line factory workers, prompting the creation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1935. CIO founder John L. Lewis was so angry at the AFL’s unwillingness to act that he got into a fistfight with another union leader at the 1935 AFL convention. Lewis, who served as the president of the United Mine Workers of America, led a cohort of eight unions out of the AFL to start the CIO. In 1937, the CIO sponsored a series of successful “sit-down” strikes in automobile factories in Flint and Detroit, Michigan, to get the car manufacturers to recognize the United Auto Workers union. The Roosevelt administration signaled an unwillingness to break up these strikes and others launched by the CIO. Its successes made the CIO more attractive to factory workers, and by the end of 1937, the conglomerate of unions had 3 million members. The CIO and other unions became closely aligned with the Democratic Party and helped many workers gain a number of basic benefits such as pensions, paid days off, and health insurance. The CIO entered a season of decline in the post–World War II era. It was torn by internal dissension over the presence of communists in its ranks, and the CIO launched a massive but failed attempt to extend union organizing to the South. The weakened CIO merged with the AFL in 1955.

The New Democratic Coalition

The New Deal helped forge an enduring coalition in the Democratic Party, uniting many who might have seemed to have contradictory priorities. Southern whites had been the base of the Democratic Party since the Civil War era. Now union members and many others in the urban North became solidly Democratic too. The most dramatic shift in allegiance came from African American voters, however. African Americans, when allowed to vote, had historically tended to vote Republican because it was the party of Lincoln and the abolition of slavery. By FDR’s reelection campaign in 1936, however, three-quarters of African American voters supported him.

The New Deal brought benefits to many African Americans, even though many parts of it discriminated against nonwhites in official and unofficial ways. Blacks and other nonwhite workers were often paid less than white workers in the same federal jobs. FDR’s agricultural programs were disastrous for many farm workers who did not own the farms. Again these workers were disproportionately nonwhite, though many poor whites also fell victim to the farming programs’ effects. Tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and migrant workers often found themselves without work as the government paid farmers subsidies to curtail production of crops and meat. And Social Security’s old-age program excluded many African Americans because they were farmworkers or domestic servants. Still, as many as four in ten African Americans did receive support or employment through New Deal programs. The WPA, in particular, gave jobs to more than a million blacks by the end of the 1930s.

The Roosevelt administration also gave unprecedented positions of power to small but influential numbers of African American leaders. One of the most prominent was Mary McLeod Bethune, who headed the National Youth Administration’s Office of Negro Affairs, which supplied jobs and training to hundreds of thousands of young blacks. Bethune was born to a cotton farming family in rural South Carolina. A devout Methodist, Bethune attended the Moody Bible Institute and once aspired to become a missionary to Africa, but she found doors closed to her because of her race. She returned to the South and became a leading advocate for Christian education for African Americans. In the early 1900s, she founded what became Bethune-Cookman College in Florida.

Taking on a variety of leadership positions in national education and civil rights organizations, Bethune befriended Eleanor Roosevelt. Bethune accepted her administration position with the National Youth Administration in 1936. With access to the president, by the late 1930s Bethune became arguably the most influential African American leader in the United States. She saw the church as having enormous potential for generating social change in the nation, but she insisted the church must live out its beliefs in order to be effective. “The church has been and must continue to be the great gateway to these spiritual influences which lead us to the realization of the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of Man. But this influence can be willed only by a living, breathing church that puts this concept into practice.”

Perhaps the most important symbolic moment for race relations during the Roosevelt administration came when Eleanor Roosevelt and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes arranged for a performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, by the great contralto singer Marian Anderson in 1939. Anderson had been refused the opportunity to perform at the city’s largest concert venue, the Constitution Hall of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the Daughters of the American Revolution over the episode. When Anderson performed on the national mall on April 9, a vast integrated throng of 75,000 spectators came to hear her sing. It was broadcast live on radio networks.4

Figure 22.8. Mary Bethune, in charge of the “Colored Section” of the NYA. Ca. 1938.

Challenging the New Deal

Regardless of the New Deal’s limitations, a majority of voting Americans believed Roosevelt had handled the Depression well. His new Democratic coalition led him to a landslide victory in 1936 over Republican presidential nominee Alf Landon. Winning all the states except Maine and Vermont, FDR trounced Landon in the Electoral College by 523 to 8 votes.

Feeling that the election had given him a renewed mandate, FDR set his sights on the primary obstacle to New Deal legislation: the Supreme Court. The court had struck down certain parts of the New Deal program. Roosevelt was frustrated by his inability to replace the aging justices, some of whom seemed determined to stay on the court as long as necessary to restrict FDR’s legislative agenda. Because the Constitution does not stipulate how many members the Supreme Court has, FDR asked Congress to institute a measure to expand the number of justices by up to six new members. This would have given FDR a solid majority of supporters on the court. But the scheme ended up damaging FDR politically.

Critics saw the “court-packing” plan as a crass politicization of the Supreme Court, which ideally was supposed to stand above the nation’s political turmoil. Even some Democrats resisted FDR’s proposal. The court, perhaps chastened by the threat of expanding its membership, approved the constitutionality of key measures such as the Wagner Act and the Social Security Act in the meantime, indicating that they were not going to stand in the way of every New Deal measure. FDR’s Supreme Court expansion proposal eventually died in Congress. By the end of the 1930s, FDR had been able to replace a number of retiring justices anyway, so the issue became moot. But Roosevelt had spent a lot of political capital on the battle, and it set the stage for the emergence of more effective political opposition to his agenda.

FDR’s electoral triumph in 1936 was clouded by the court-packing controversy. Then the United States spiraled into a renewed economic downturn in 1937. The recession brought into question whether all of FDR’s huge spending programs had been for naught. A group led by Democratic senators such as Josiah Bailey of North Carolina drew up a “Conservative Manifesto,” questioning the New Deal’s dependence on spending the public’s money as an answer to the nation’s economic woes. They encouraged policies that would lower taxes and encourage private investments in businesses and the stock market as well as balance the federal budget and restore confidence in the government’s stability. They urged the administration to steer away from the temptations of socialist state ownership of business and mass government employment programs. American private enterprises were not foolproof, they acknowledged, but “they are far superior to and infinitely to be preferred to any other so far devised. They carry the priceless content of liberty and the dignity of man. They carry spiritual values of infinite import, which constitute the source of the American spirit.” Increasing numbers of southern Democrats, along with the national Republican Party, wanted to keep the New Deal from undermining the American ideal of free market capitalism.

The “Conservative Manifesto” represented the beginnings of the modern conservative movement in America. From the 1930s forward, political battle lines in America were often drawn around the question of whether more government or less government was needed for citizens to flourish. The New Deal had undoubtedly alleviated some of the worst effects of the Depression, but it also represented a phenomenal increase in the size and intrusiveness of national government agencies. Of course, some Americans of a more radical persuasion wanted the New Deal to go further into state ownership and collectivism represented by socialism or communism. The Cold War, beginning in the late 1940s, would help many Americans understand the murderous extremes to which communism could run. In the meantime the specter of fascism and Nazism began to darken America’s international horizons.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Biles, Roger. The South and the New Deal. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Brinkley, Alan. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression. New York: Vintage, 1982.

Carpenter, Joel A. Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Greenberg, Cheryl Lynn. “Or Does It Explode?” Black Harlem in the Great Depression. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Kelley, Robin D. G. Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Leuchtenberg, William E. The Perils of Prosperity, 1914–1932. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1958.

McElvaine, Robert S., ed. Down and Out in the Great Depression: Letters from the Forgotten Man. Rev. ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Sitkoff, Harvard. A New Deal for Blacks: The Emergence of Civil Rights as a National Issue: The Depression Decade. Classic ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Terkel, Studs. Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression. New York: Pantheon Books, 1970.

Walker, Melissa, ed. Country Women Cope with Hard Times: A Collection of Oral Histories. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2012.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. 25th anniv. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

4 “Marian Anderson Sings at the Lincoln Memorial,” YouTube video, 1:50, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XF9Quk0QhSE.