26

Civil Rights and the Great Society

When President John F. Kennedy spoke of a “new frontier” in his acceptance speech at the 1960 Democratic National Convention, it seemed that the nation was preparing to turn a page. Eight years of mainstream Republican politics were about to be replaced with the administration of the fresh-faced, forty-three-year-old Democrat. But Kennedy was also a firm cold warrior. “We shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty,” he declared in his 1961 inaugural address. One of the most resonant moments of Kennedy’s presidency came when he visited West Berlin in 1963, declaring in solidarity, “Ich bin ein Berliner.” The city had become a democratic island in the midst of communist East Germany. Two years earlier East Germans with Soviet support had erected the Berlin Wall to keep its residents from fleeing to freedom on the western side.

The “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech was an important symbol of Kennedy’s opposition to communist power, but the greatest international challenge of his presidency had come in 1962, with the Cuban missile crisis. In 1961, Kennedy’s administration had tentatively backed an attempt by anti-communist Cuban exiles to overthrow Cuba’s communist regime, headed by Fidel Castro. But Castro’s forces had destroyed the invading force at the Bay of Pigs in southern Cuba in April 1961. The Bay of Pigs fiasco had convinced the Soviets to begin an escalation of defenses in Cuba to ward off any future American or American-backed attempts to dislodge Castro. This precipitated the US-Soviet clash over Cuba, which one historian has called the “most frightening military crisis in world history.” This was the moment the Cold War came the closest to going hot, with the possibility of unfathomable destruction if Russia or the United States had used nuclear weapons.

By mid-1962, the Soviet Union was installing nuclear missiles and launchers in Cuba. The weapons easily could have reached the US mainland. (The United States likewise had missiles in position to hit Cuba.) US intelligence underestimated how formidable the Soviet presence on Cuba was. For example, the Soviets had a military force of 42,000 on the island, twice what American officials believed. Kennedy insisted that the Soviets not put nuclear missiles in Cuba, and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev denied that they had. American spy planes revealed otherwise. Kennedy and his advisors debated a range of strategies but settled on enforcing a blockade (technically, a “quarantine”) of Cuba, preventing the Soviets from bringing more military equipment to the island. The world watched breathlessly as Soviet ships moved toward the island. But at the last minute, the ships turned around, as the Soviets decided not to provoke the ultimate confrontation.

But nuclear missiles remained in Cuba, and Kennedy demanded that these be removed or the United States would launch a strike to eliminate them. Tensions reached their highest point in late October 1962 when the Soviets shot down an American U-2 spy plane over Cuba. Khrushchev finally agreed to remove the missiles, however, if the United States would commit to not invading Cuba. (Kennedy also secretly let the Russians know that he would remove US missiles from Turkey.) Khrushchev had overplayed his hand, as he was unwilling to face the consequences of placing nuclear missiles in Cuba, perhaps hoping Kennedy would not respond decisively. The outcome of the Cuban missile crisis undoubtedly contributed to Khrushchev’s removal as Soviet premier in 1964. Kennedy, likewise, has been criticized for letting the Cuban situation get out of control and for failing to make clear to the Soviets early on that the United States would not tolerate nuclear missiles in Cuba. Some military leaders and Cuban exiles also fumed that Kennedy had missed multiple opportunities to invade Cuba and remove Castro, allowing Castro’s oppressive government to stay in place. Whatever else we might say about Kennedy’s and Khrushchev’s roles, however, the great Cold War powers had come to the brink of nuclear war, and thankfully they had backed away.

The Kennedy Presidency

Although Kennedy continued America’s commitment to countering the communist threat, his presidency undoubtedly represented a new era of American politics. Kennedy was from a prominent family of Catholics in Massachusetts, and the nature of his faith became a major issue in the 1960 election. Some critics suggested that a Catholic was necessarily divided in political loyalties between the United States and the Vatican, the seat of power of the Roman Catholic Church. Kennedy vociferously denied that he would be a tool of the pope. Speaking before a Houston ministerial association, he said he believed in an “absolute” separation of church and state. “I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for president, who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters—and the church does not speak for me,” Kennedy declared.

Kennedy’s explanations were enough to help hold together Franklin Roosevelt’s Democratic coalition of the urban North, African Americans, and the white South. He defeated Richard Nixon of California, Eisenhower’s vice president. The staunch segregationist Harry Byrd of Virginia did draw away some electoral votes from Kennedy in the Deep South, but Byrd did not attempt a coordinated campaign, so his outcome did not match that of Strom Thurmond’s “Dixiecrat” candidacy of 1948. Helped by his vice-presidential nominee, Texas senator Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy won most of the South. He also won parts of the Midwest and much of the Northeast. He won the Electoral College by more than 80 votes, but out of almost 69 million cast, Kennedy only garnered 100,000 more popular votes than Nixon.

Kennedy was an ideal candidate for the new era of televised politics. In September 1960, Kennedy and Nixon met in the first televised presidential debate in American history. Kennedy seemed relaxed and nimble during debate, while Nixon was visibly uncomfortable. Although Nixon performed better in subsequent debates, a negative public impression about Nixon had already formed. From 1960 forward, presidential candidates had to cultivate an image that would translate well on live television and, more recently, on the internet.

Much of Kennedy’s presidency was devoted to countering Soviet ambitions in foreign affairs, military buildup, and the space race. Kennedy called on NASA to land a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s, but the Soviets still seemed to have the edge in space exploration. Just as they had put Sputnik in orbit as the first space satellite, the Soviets also flew the first manned space mission in 1961. But in 1962, the United States sent the former Marine pilot and future senator John Glenn on a successful mission to orbit the earth. Many in America saw Glenn’s Mercury Project mission as the moment America caught up with Russia in exploring the heavens. During Richard Nixon’s first term, the Apollo missions would fulfill Kennedy’s vision of a moon landing. In late 1968, Apollo 8 astronauts read from Genesis 1 during the national telecast of their moon orbit. Then, on July 20, 1969, astronaut Neil Armstrong, commander of the Apollo 11 mission, became the first person to walk on the moon. Armstrong said that stepping onto the surface of the moon was “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Figure 26.1. Astronaut John H. Glenn Jr. dons his silver Mercury pressure suit in preparation for launch of Mercury Atlas 6 rocket, January 20, 1962.

Like Truman and Eisenhower, Kennedy was committed to stopping the growth of communist influence. This desire played out most obviously in the Cuban missile crisis. But it also led the United States to seek to protect South Vietnam from communist takeover. During his tenure Kennedy oversaw the expansion of US military personnel in Vietnam from 1,000 to almost 17,000. For a time Kennedy’s administration sought to work with the corrupt and unpopular South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem. But when a coup removed Diem in 1963, US officials did nothing to stop it or to save Diem’s life. Kennedy seemed to believe he could not turn the civil war in Vietnam in favor of the anti-communists in South Vietnam without a major influx of hundreds of thousands of American troops. He was hesitant to do this, especially without a reliable partner in South Vietnam. But he was also convinced the United States should not abandon South Vietnam to communist power. By the end of his presidency, it was unclear which direction Kennedy would have taken in Vietnam, whether withdrawal or escalation. Johnson, Kennedy’s successor, would choose escalation.

Civil Rights

Kennedy was conflicted about how aggressively to move on civil rights issues as well. He was sympathetic to the civil rights movement, but he also did not wish to alienate white southern Democrats, on whom his political fortunes in the South depended. But civil rights protestors persisted in their attacks on Jim Crow segregation. By 1961, the Supreme Court had repeatedly ruled against segregation on buses and bus terminals, yet many bus stations remained segregated and closed to blacks. Believing they had the law and a rising tide of public opinion on their side, activists decided to launch the “Freedom Rides” in 1961. Freedom riders insisted on gaining access to segregated bus terminal facilities. Leaders affiliated with groups including the Congress of Racial Equality informed the Kennedy administration that the rides were going to happen, hoping to secure some federal protection from the violence that was likely to ensue. The administration took little action, however, permitting vicious attacks on the riders—both blacks and whites—by white adversaries in places such as Anniston, Alabama. In Birmingham dozens of men affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan assaulted the freedom riders with chains and pipes. The activists had to call off the rest of the trip, fearing for their lives. But hundreds more activists followed in their wake, finally prompting the Interstate Commerce Commission to order an end to segregation in the bus stations.

Figure 26.2. Integration at Ole Miss[issippi] Univ[ersity] / MST, by Marion S. Trikosko, October 1, 1962. Photograph shows James Meredith walking on the campus of the University of Mississippi, accompanied by US marshals.

The Kennedy administration tended to react to events in the civil rights movement rather than taking the initiative. The administration’s hesitancy opened the door for more episodes, such as the clash over integrating the University of Mississippi in 1962. An African American Air Force veteran named James Meredith sought to become the first black student at the university, but Mississippi governor Ross Barnett vowed to stop it from happening. He called the defense of segregation a “righteous cause” and promised that Mississippi whites would not “drink from the cup of genocide.” Barnett vowed to keep order at the university as Meredith prepared to enroll, but then he allowed Mississippi state police to withdraw when white rioters clashed with federal marshals on the campus in Oxford. Hundreds were injured, and two people died in the ensuing violence before attorney general Robert Kennedy sent in thousands more federal personnel to keep the peace and protect Meredith. Meredith, guarded by federal officials, managed to stay at the university and graduated in 1963 (he had come in with significant transfer credit).

In 1963, Martin Luther King and other leaders targeted Birmingham, Alabama, for the next great campaign against segregation. Birmingham had a reputation as having the most entrenched system of segregation and white supremacy in the nation. King guessed that when the campaign began, hostile whites led by Birmingham police commissioner Bull Connor would try to silence the protestors through violence. This would draw more sympathy to the civil rights movement from a national audience. Early in the Birmingham campaign, King was arrested and wrote his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” the most influential essay of his career. Addressing his “fellow clergymen” who were asking civil rights activists to moderate their approach, King explained why the activists could wait no longer for change. They had been waiting since the founding of the American colonies for an end to racial oppression, he said. The champions of civil rights were “standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence,” he argued. They were not extremists, King said, unless you considered figures such as Jesus, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln as extremists too.

The civil rights activists ratcheted up the pressure in Birmingham when they sent 1,000 students and young children on a march into the city. Bull Connor arrested most of them and ordered the leaders not to send anyone else marching into the city. When the protestors disobeyed Connor’s order, Connor snapped and turned the city’s police and firefighters against the marchers. Using clubs, attack dogs, and high-pressure hoses, the city forces brutalized many of the marchers, including some children. Many of the marchers, including prominent Baptist pastor Fred Shuttlesworth, were knocked unconscious by blasts from the water cannons. Some of the protesters were so incensed by Connor’s tactics that they gave up on nonviolence and began retaliating, though with far less force (generally they threw rocks and bottles at the police).

Much of the violence in Birmingham was shown on national television. It embarrassed many who were watching, including President Kennedy. Kennedy determined that it was time for him to throw his weight behind a new civil rights bill to prohibit segregation in public facilities and to ban discrimination on the basis of race, religion, or sex. Civil rights activists knew that to receive this kind of presidential backing represented a major milestone. But their joy was dampened the night Kennedy announced his support for the bill when World War II veteran and NAACP worker Medgar Evers was shot in the back outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi. The murderer, Byron De La Beckwith, was not convicted of the crime until the 1990s, as all-white juries originally deadlocked in trials in 1963. Evers was buried in Arlington National Cemetery outside of Washington, DC.

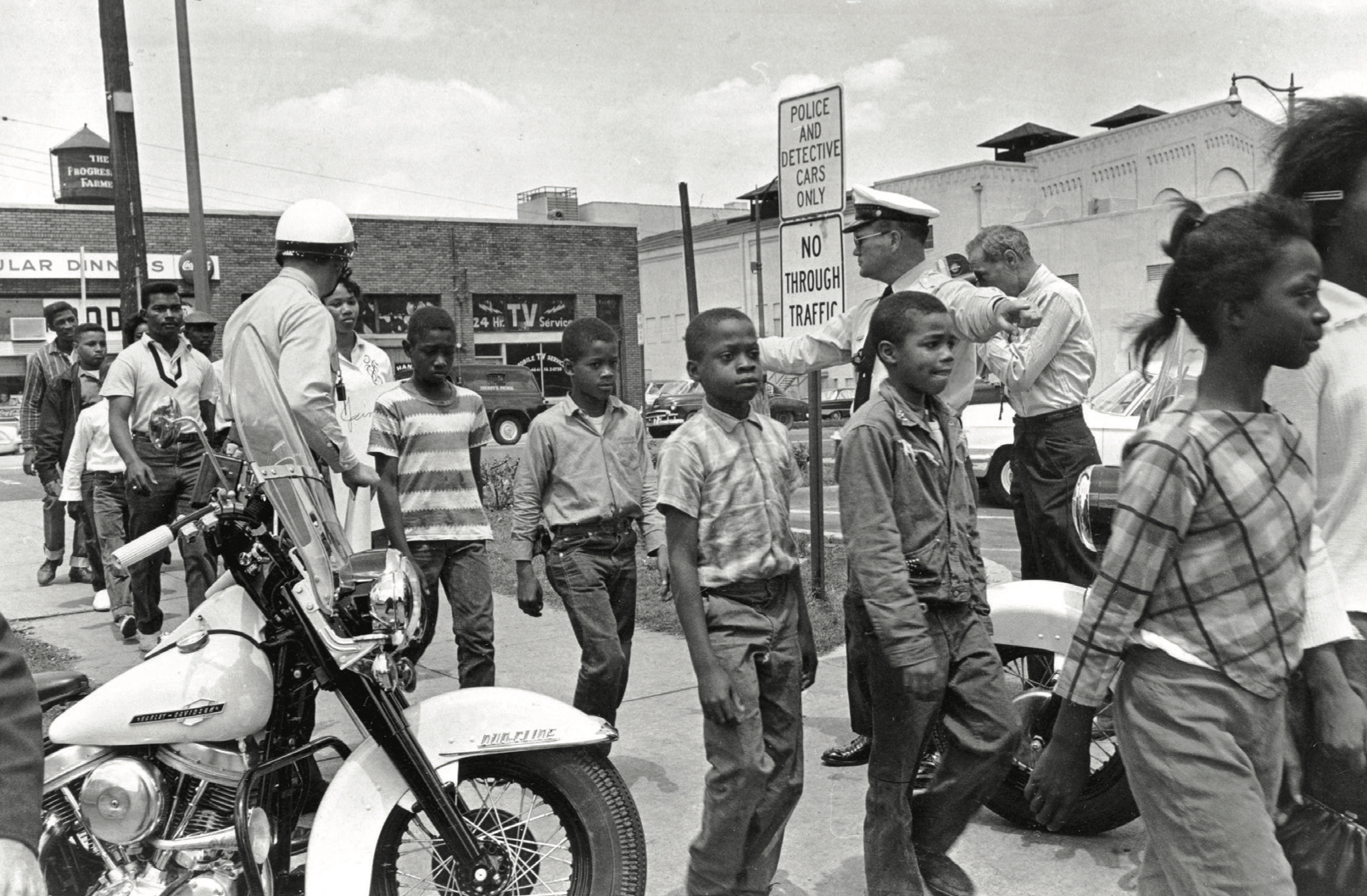

Figure 26.3. In this May 4, 1963, photo, police lead a group of black schoolchildren to jail after their arrest for protesting against racial discrimination near city hall in Birmingham, Alabama.

Civil rights leaders were mixed in their view of Kennedy’s proposed law, with some fearing it would become a meaningless gesture without real legal authority. Bayard Rustin of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and A. Philip Randolph, a longtime labor and civil rights activist, organized the August 1963 March on Washington to promote the adoption of a far-reaching civil rights bill. They originally envisioned the march as including a sit-in at the Capitol, but the Kennedy administration worked feverishly to moderate the event’s tone and aims. By August 28, it had become a short march, concluding with a number of speakers at the Lincoln Memorial. Critics such as the Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X called it the “Farce on Washington.” Nevertheless, the March on Washington drew a titanic crowd of some 250,000 people to the national mall. Popular singers including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Mahalia Jackson participated. But Martin Luther King gave the most memorable address in his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.” Filled with allusions to the Bible and to America’s founding, it reads, in part:

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. . . .

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low. The rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; “and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together” [Isa 40:4–5]. . . .

. . . When we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last.”11

As moving as King’s speech was, it did not break the logjam in Congress over the proposed civil rights legislation. Three weeks after the March on Washington, in a brutal reminder of the enduring racial hostility in the South, an explosion devastated the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham on a September Sunday morning. The blast killed four girls ranging in age from eleven to fourteen. Federal investigators identified four members of the Ku Klux Klan as those who had planted the dynamite, but no prosecutions went forward until years later.

The Kennedy Assassination

Anticipating a tough reelection campaign in 1964, President Kennedy and his wife, Jacqueline, made a visit to Texas in November 1963. On November 22, the Kennedys took a ride in an open-air motorcade through Dallas. As their car passed the Texas School Book Depository building, the Kennedys and their entourage came under fire. President Kennedy suffered a fatal shot to the head. A man named Abraham Zapruder took the most complete video footage of the assassination, having brought a home movie camera to film Kennedy’s visit but hardly expecting to document an assassination. The gruesome scene captured in the Zapruder film has become one of the most studied and controversial pieces of video in American history.

Dallas police quickly arrested Lee Harvey Oswald, who worked at the book depository, and charged him with killing Kennedy. Just days later Oswald himself was shot to death by a Dallas nightclub owner named Jack Ruby when Oswald was being moved by police. (News cameras caught the killing of Oswald happening live.) The circumstances and gravity of Kennedy’s killing spawned an industry devoted to studying the assassination and proposing theories about how it happened and who was involved. President Lyndon Johnson appointed a commission led by Chief Justice Earl Warren to investigate. The Warren Commission determined that Oswald was the lone shooter and that he was not part of a larger conspiracy. Oswald was an unstable person with communist sympathies who had once lived in the Soviet Union for almost three years. Although US officials were generally content with the Warren Commission report, others have suggested that Oswald may not have been the only gunman or that he may have been part of a plot by the Soviets, Cubans, or organized crime members to kill Kennedy.

Kennedy had served as president for fewer than three years, so his accomplishments were necessarily limited. But the assassination and the remarkable dignity shown by Jacqueline Kennedy in the days following his death enshrined his status as an American martyr. Lyndon Johnson became the new president, sworn in on the presidential airplane Air Force One as it went back to Washington. Johnson believed the national government should honor Kennedy’s memory by fulfilling his legislative agenda, including in the area of civil rights. Echoing Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Johnson told Congress, “Let us here highly resolve that John Fitzgerald Kennedy did not live or die in vain.”

Johnson, Poverty, and Civil Rights

Kennedy had picked Lyndon Johnson as his vice president for regional balance on the presidential ticket and because of Johnson’s remarkable skills in dealing with Congress. Johnson grew up in rural Texas, was almost a decade older than Kennedy, and had little of Kennedy’s polish. But Johnson was a master of the legislative process in Congress and had an unparalleled gift for persuading congressmen and senators to support his proposals. That gift of persuasion did not entirely translate to the presidency; nevertheless, Johnson would oversee far more dramatic legislative change than Kennedy had. One of Johnson’s first moves was to drive through an $11 billion income tax cut that Kennedy had proposed, which boosted consumer spending and helped create a million new jobs per year.

Johnson also moved forward with another Kennedy initiative that Johnson called the “War on Poverty.” A little more than 20 percent of the nation lived below what experts designated the “poverty line.” The American poor did not make enough money to meet basic needs for themselves and their families. (Critics observed that many of those designated as “poor” certainly had more affluence than the abject poor of the Great Depression era.) Johnson was convinced, along with other political liberals, that the right government programs could better the lot of the poor. Instead of making people permanently dependent on government, liberals believed, the best kinds of “welfare” programs would empower the poor to improve their job status and income and to ascend out of poverty. Conservatives were wary, believing top-down government programs inevitably became bloated and often did as much damage as good. Conservatives supposed that if anyone could help the poor, it was the poor themselves, as well as “mediating institutions” on the local level: families, schools, and churches. National government bureaucrats could never understand how to be of real assistance. In spite of these criticisms, Congress passed the $1 billion Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which created the Office of Economic Opportunity and a host of job training and community development programs. Much of the bill’s funding went to pay program administrators.

Getting the long-stalled Civil Rights Act passed would be difficult. Johnson knew that many of his fellow southern Democrats would stridently oppose the measure and seek to kill it by filibustering in the Senate. (Filibusters entailed endless talk and discussion about the bill, which senators could only end by a vote for cloture, which at the time required a two-thirds majority.) In 1957, South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond had set the record for the longest filibuster by a single senator, speaking for more than twenty-four hours in opposition to another civil rights measure. But Johnson wielded his great powers of persuasion to bring enough Republicans on board, and Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The law prohibited racial discrimination by businesses that served the public such as restaurants, theaters, and hotels, and it directed states and towns to repeal remaining Jim Crow laws related to segregation. In what would become a common move by the federal government, the act warned that any school or other institution that received federal dollars could risk a loss of funding if they maintained any discriminatory policies. It also banned employment discrimination on the basis of race and color as well as sex or religion. The Civil Rights Act was a landmark measure, although it left many areas unaddressed such as voting rights. It also did not propose any substantive solutions to “de facto” segregation, meaning segregation that depended on local practice and custom rather than documented laws or policies (“de jure” segregation). De facto segregation was pervasive in many parts of American society outside the South. Segregationist policies were often more blatant in the South, but in some other areas of the country, they were just as entrenched.

The 1964 Election

Johnson wanted to secure a major victory in the 1964 presidential election, which would give him a mandate for his legislative agenda. His War on Poverty had fueled a backlash in the conservative movement, opening the door for Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona to win the Republican nomination. Goldwater defeated Republican opponents coming from the establishment/Eisenhower segment of the party. Goldwater was an articulate and remarkably frank defender of conservative orthodoxy, but he was unwilling to moderate his rhetoric to score political points, so he was an ideal opponent for Johnson to defeat by a large margin. Knowing that many had accused him of political extremism, Goldwater gladly embraced the label. “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” he told the Republican National Convention, and “moderation in pursuit of justice is no virtue.” Johnson trounced Goldwater in the Electoral College, 486 votes to 52. Johnson also won 61 percent of the popular vote nationally.

Goldwater’s losing candidacy was of enormous consequence, however, because it was an early indicator of massive shifts happening in regional political alliances. First, the Arizona senator’s nomination signaled that leadership in the Republican Party was moving toward the West and Southwest. Most of the party’s presidential nominees for the next four decades would hail from places such as Arizona, California, and Texas. One of those future nominees, Ronald Reagan of California, gave a major speech on Goldwater’s behalf in the fall of 1964, explaining his tough stance on communism and opposition to top-down government programs and high taxes.

Citing the Bible, the American Founders, and Abraham Lincoln, Reagan explained why America could never cut a peace deal with the Soviets or leave the people of Cuba and Eastern Europe to languish under oppression. “Should Moses have told the children of Israel to live in slavery under the pharaohs?” Reagan asked. “Should Christ have refused the cross? Should the patriots at Concord Bridge have thrown down their guns and refused to fire the shot heard ’round the world? . . . You and I have a rendezvous with destiny. We will preserve for our children this, the last best hope of man on earth, or we will sentence them to take the last step into a thousand years of darkness.”

Barry Goldwater’s candidacy also signaled the end of the “solid South” for Democrats. Even though Johnson was a Texas Democrat, his support for government expansion and for the Civil Rights Act alienated many white southerners, who began defecting to the Republican Party and to Goldwater. Goldwater’s only regional pocket of support was in the Deep South, where he won the states from Louisiana to South Carolina. Leading southern Democrats also shifted to the Republican Party: Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, for example, switched his affiliation to the Republicans during Goldwater’s campaign. Democrats retained a number of key offices in the South and could still win some southern states in presidential contests. But the long-term trend was toward a new “solid South,” this time in the Republican column.

The Great Society

In May 1964, as part of his reelection campaign, Johnson had explained his vision for the “Great Society” in America. “The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all,” Johnson declared. “It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time. But that is just the beginning. The Great Society is a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and to enlarge his talents. It is a place where leisure is a welcome chance to build and reflect, not a feared cause of boredom and restlessness. It is a place where the city of man serves not only the needs of the body and the demands of commerce but the desire for beauty and the hunger for community.” Spurred on by his overwhelming electoral victory in November 1964, Johnson set out to pass arguably the most ambitious legislative program since the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. One of his measures vastly increased federal dollars for education, as Johnson and his supporters saw well-funded schools as a key to getting kids out of poverty. Critics argued that all the federal funding in the world could not change the factors that made for the best education: motivated teachers teaching safe and healthy kids who were part of supportive family and social networks.

Johnson also wanted to expand the “safety net” for older Americans, a process begun in the 1930s with the creation of Social Security. Half of Americans sixty-five and older in 1965 had no health insurance, and serious illnesses or injuries could easily bring financial ruin to the uninsured. Of course, older people were more likely to develop serious long-term ailments, so it was difficult for many of them to afford health insurance. Relying almost exclusively on Democratic votes, Johnson passed the Medicare program, which increased Social Security taxes to cover hospital stays for the elderly and offered subsidized health insurance to help cover other types of medical expenses for older Americans.

Medicare has become a fixture of old-age medical care in America. But the rising percentage of Americans over the age of sixty-five and rising costs of medical services have combined to make Medicare enormously expensive. In recent years Medicare expenses alone (not including the “Medicaid” program for low-income Americans) represented about 14 percent of all federal expenditures. Critics have noted that widespread insurance coverage has fed the rapid rise in medical costs. Doctors and patients have little incentive to keep costs down when patients are covering only a fraction of those costs “out of pocket.” Battles over the 2010 Affordable Care Act suggested that Americans were still grappling with the tension between expanding health insurance coverage and the skyrocketing costs associated with doing so.

Democrats also pushed through immigration reform. At first glance the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 seemed to be of lesser short-term consequence than the other pillars of the Great Society. But this law would have transformative effects on the demographics of American society. The law was originally intended to even out the countries of origin of immigrants coming from Europe and to allow more people to come from southern and eastern Europe in particular. It abolished the previous national quota approach, which critics viewed as outdated and racist because of the preferences the United States had previously given to prospective immigrants from northern and western Europe. The 1965 law put the focus of immigration on people who had relatives in the United States and people with certain job skills. But the immigration law had many unintended consequences, and it set the stage for a new wave of immigrants from non-European nations. Unauthorized immigrants from Mexico and Central America continued to be an issue. But Mexico also became one of the top sources of legal immigrants to the United States, along with Latin American nations such as the Dominican Republic and Cuba and Asian nations such as Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan, and India. China produced the largest number of Asian immigrants after 1965. (The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act had been repealed during World War II.) By the time of the 2010 US Census, the number of Chinese Americans was approaching 4 million.

The Johnson administration also saw major new initiatives related to environmental regulation. Spurred by the book Silent Spring (1962) by marine biologist Rachel Carson, many Americans had become concerned about the damaging effects of mass American industry, farming, and transportation on the natural world. (Carson was especially focused on the threat posed by indiscriminate use of toxic pesticides in agricultural businesses.) The landmark 1963 Clean Air Act encouraged states and towns to control air pollution. Congress added a number of major amendments to the Clean Air Act over several decades, accounting for new threats and technological advances such as the ability to control pollutant emissions from automobiles. Congress also passed measures in the mid-1960s intended to encourage clean water and to stop the pollution of rivers, lakes, and oceans.

Likewise, the Wilderness Act of 1964 set aside millions of acres of land the government protected from development, believing it was important to maintain large tracts that are “untrammeled by man.” Over time the National Wilderness Preservation System has designated more than 100 million acres in America as protected wilderness. Critics of the wilderness system (and of the associated power of the president to designate areas as national monuments) say it hurts economic opportunity in the affected areas by cutting them off from even modest development. In 1970, Richard Nixon authorized the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, which would become the most influential environmental regulatory unit of the federal government.

Freedom Summer and the Voting Rights Act

Civil rights reform continued to be one of the most difficult and controversial parts of Johnson’s Great Society initiatives. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a major success, but activists believed they still had a long way to go to secure adequate education and voting rights for nonwhites. Led by the civil rights umbrella organization called the Council of Federated Organizations (including members from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and others), civil rights workers launched “Freedom Summer” in 1964 in Mississippi. They sought to register black voters and to set up “Freedom Schools” for African American children. The schools, meeting outside of the public school system—often in church basements—focused on civics and humanities education and inculcated the ideals of the civil rights movement. Freedom Summer led to another reaction among white supremacists, with Klansmen murdering three more civil rights workers near Philadelphia, Mississippi.

The Council of Federated Organizations also worked to establish an alternative Democratic Party in Mississippi, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), to challenge the power of the white-dominated official Democratic Party in the state. The MFDP believed they had a real chance at some kind of recognition from the national Democratic Party in light of Johnson’s leadership on the Civil Rights Act. But Johnson saw the MFDP as troublemakers and tried to fend off any kind of formal participation by them at the party’s 1964 national convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

The controversy over the MFDP set the stage for the eloquent appeals for civil rights of Fannie Lou Hamer, who came from a poor sharecropping family in Ruleville. For her efforts at registering people to vote and speaking up for civil rights, Hamer was beaten and tortured by policemen and prisoners at a jail in Winona, Mississippi. A person of deep Christian faith, Hamer shared Bible verses with the jailer’s wife after the beating and asked the jailer himself, “[Do you] ever wonder how you’ll feel when the time comes [that] you’ll have to meet God?” The police who oversaw her torture were tried in court, but an all-white jury exonerated them. Hamer pressed on, working for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee for ten dollars a week. During the day Hamer would try to get sharecroppers to register to vote; at night she and other activists would meet in church rallies, singing gospel music and urging one another to keep going.

In August 1964, Hamer testified before the Democratic Convention on behalf of having the MFDP recognized. Her testimony and others were carried live on national television, and President Johnson was so concerned about the damage the MFDP was doing that he interrupted the coverage of Hamer with a press conference of his own on an unrelated topic. Hamer told the convention, “If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America.”12 The MFDP brought a total of sixty-eight delegates and alternates to the convention, but Democratic officials proved unwilling to give them anything more than token representation. The MFDP ended up getting no delegates seated at all.

In spite of the disappointment at the Democratic convention, civil rights activists kept working for reform, setting their sights in early 1965 on Selma, Alabama. Although that town of 29,000 had a majority of African Americans, fewer than 400 blacks were registered to vote in Selma. The white-run registration board would disqualify prospective voters for the most trivial errors in their applications. Civil rights leaders, recalling their experiences in Birmingham, expected Selma authorities to overreact and damage the segregationist cause. They were right. More than 3,000 demonstrators were jailed, including Martin Luther King and future congressman John Lewis. Selma police brutalized a number of protestors, beating them with nightsticks and shocking them with cattle prods.

In March 1965, King organized a protest march that would go from Selma to the Alabama state capital at Montgomery. As Lewis and other leaders led a crowd of 600 marchers toward the Edmund Pettis Bridge on the edge of Selma, Alabama police stood at the other end, telling them, “Go back to your church.” When the protesters did not disperse, the police advanced, swinging their clubs. A policeman struck Lewis viciously, leaving him with a fractured skull. The police also unleashed tear gas on the crowd. Seventy marchers were ultimately hospitalized with injuries from the clash on “Bloody Sunday” at Selma. Federal officials belatedly allowed the march to go forward with protection two weeks later, with tens of thousands of supporters finally gathering at the Montgomery statehouse and singing “We Shall Overcome,” a gospel song that had become one of the movement’s anthems.

President Johnson was always attuned to political timing, and he knew Bloody Sunday had opened the door again to major civil rights reform. In August 1965, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, which Congress had passed with bipartisan support over the resistance of southern members. The act authorized the Justice Department to take action against discriminatory practices in voter registration and in voting itself. The act increased the number of African American adults registered to vote. In the six Deep South states of particular concern to the Justice Department, the percentage of eligible African Americans registered went up from less than a third to almost half in one year. The original promise of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, that of color-blind voting rights, was being fulfilled.

Figure 26.4. Participants, some carrying American flags, in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965. Photograph by Peter Pettus.

The Limitations of Civil Rights Reform

By 1965, the civil rights movement had an impressive list of successes to its credit, from Brown v. Board of Education to the Voting Rights Act. But some worried that the legal changes could not address the intractable social and economic inequality of African Americans, a status that had its roots in slavery and the tribulations of the Reconstruction era. The inadequacies of civil rights reform were cast into sharp relief the same month as the signing of the Voting Rights Act, when the largely African American neighborhood of Watts in Los Angeles exploded in riots. The violence in Watts led to dozens of deaths and tens of millions of dollars’ worth of property damage from looting and arson. Where much of the civil rights movement had been animated by the principles of nonviolent resistance, the Watts rioters struck out against white motorists and businesses. This resulted in a harsh crackdown on black rioters by Los Angeles police, turning Watts into a veritable war zone. Similar episodes of violence and rioting spread to other American cities over the next few years.

Some observers suggested that the problems in black communities like Watts had less to do with a lack of political rights and more to do with a breakdown of family and social support networks. Assistant secretary of labor and future US senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan made this argument in his controversial 1965 report “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” Moynihan contended rampant divorce, out-of-wedlock pregnancies, and dependence on government welfare programs had been toxic to African American families. Moynihan said that the black family was trapped in a “tangle of pathology” that made it difficult for African American teenagers to break out of poverty. Moynihan asserted that if the federal government really wanted to bring about full equality for African Americans, it needed to do whatever it could to enhance the “stability and resources of the Negro American family.” Moynihan, who soon joined the faculty at Harvard, seemed genuinely interested in helping African American families. But critics saw the report as smug and patronizing. Congress of Racial Equality leader James Farmer saw Moynihan as blaming the oppressed instead of the oppressor. “We are sick to death of being analyzed, mesmerized, bought, sold, and slobbered over, while the same evils that are the ingredients of our oppression go unattended.”

Some disillusioned black critics questioned the goals of the civil rights movement itself. Returning to themes of the early twentieth-century debates between Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois, some argued that blacks would be better off if they remained separate from whites. Among the most provocative advocates of this view was Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X. The Nation of Islam was a distinctly American version of the Muslim religion. The Nation of Islam had emerged in urban America during the Great Depression. Malcolm was born Malcolm Little and was the son of a Baptist pastor, but he rejected his parents’ faith. While Malcolm was once serving jail time for burglary, his brother told him about the Nation of Islam. Malcolm converted to the Nation and changed his last name to X because he said his surname was a name imposed on his ancestors by slave owners.

Malcolm argued that blacks should build their own strong institutions and largely avoid cooperation with whites, whom they could not trust. He generated great controversy when he said President Kennedy’s assassination was a matter of “chickens coming home to roost.” He fell out with the Nation of Islam’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, but Malcolm also condemned Martin Luther King, calling him a “chump” and a “fool” for his focus on integration. Malcolm broke with the Nation of Islam in 1964, and after going on a traditional Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, he converted to a more orthodox form of Sunni Islam. In 1965, Malcolm was assassinated, likely by enemies from the Nation of Islam. Some have speculated that US officials may have played a role in Malcolm’s death.

Malcolm’s book The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965), which he wrote with Alex Haley, was one of the most compelling spiritual biographies in American history. It powerfully addressed the experience of African American alienation and the trials of Malcolm’s relationship with the Nation of Islam. Malcolm and the Nation of Islam attracted some high-profile African American converts, including the most accomplished heavyweight boxer of the era, Cassius Clay. Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964. Ali cited his commitment to the Nation of Islam in 1967 when he was drafted but refused to enlist in the army. He was stripped of his boxing title when he was convicted of draft evasion, but the Supreme Court overturned his conviction in 1971, arguing that Ali did not receive fair consideration for his claim of conscientious objector status. Like Malcolm X, Ali had gravitated toward a mainstream version of Sunni Islam by the early 1970s.

The Supreme Court, Individual Rights, and the Public Exercise of Religion

The school desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education heralded an aggressive era for the Supreme Court, which routinely sought to expand the scope of the First and Fourteenth Amendments and of other constitutional protections for individuals. Sometimes the aggressive decisions of Chief Justice Earl Warren’s court were warmly received by a wide range of Americans, while other decisions caused controversies that persist in America today. Previous Supreme Courts had sometimes been profoundly traditional, even seeming to resist the plain implication of the Constitution on issues such as racial equality. Now the Supreme Court positioned itself as a leader on social change and individual rights in America. If legislators would not mandate cultural and legal advances, the Supreme Court might do so instead. For example, in cases such as Miranda v. Arizona (1966), the court came down on the side of the rights of people accused of crimes. In Miranda, a narrow majority of the justices mandated that a suspect must be advised of his or her legal rights before interrogation can proceed. They argued that the Fifth and Sixth Amendments protected the accused against self-incrimination and guaranteed them the right of representation and that law enforcement officials were obligated to tell the accused about those protections. The court in Miranda said police must inform alleged criminals that they have the right to remain silent, that any statements they make can be used against them in court, and that they have the right to consult with an attorney. This became known as the “Miranda warning,” which became a fixture of many arrest scenes in movies and on TV. Dissenting justices argued that the Miranda requirement went far beyond what the Constitution said about the rights of the accused and that it would set the stage for innumerable criminals to be released on technicalities.

The Supreme Court also made a key decision on the freedom of the press in New York Times v. Sullivan (1964). This case was intertwined with the ongoing controversies related to civil rights, as a city commissioner in Montgomery, Alabama, sued the New York Times for running an advertisement that characterized the white backlash and police crackdowns against civil rights protestors in Montgomery as a “wave of terror.” Under Alabama law this statement could be construed as libel because it damaged the reputation of a public official. Alabama courts found for the commissioner and awarded him $500,000 in damages, but the Supreme Court unanimously overturned the decision. They struck down Alabama’s libel law, contending that it violated the First Amendment. Libel in the press required clear evidence of “actual malice,” justices said, or knowledge that the statement in question was false, or at least “reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” This was a much higher standard for libel than Alabama’s definition, and New York Times v. Sullivan helped foster America’s no-holds-barred media environment when it comes to criticizing public officials.

Another of the court’s crucial decisions during this era was Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), in which the court struck down a Connecticut state law against contraceptives, including drugs or devices intended to keep a woman from getting pregnant. Estelle Griswold, director of Planned Parenthood of Connecticut, had been charged with distributing contraceptives. The Supreme Court overturned Griswold’s conviction and struck down the state’s law against contraception. The justices based their ruling on the idea that people had a constitutional right to privacy, even though that right was not stipulated anywhere in the Constitution. Neither did the Constitution suggest that the Supreme Court must strike down state laws that restricted privacy. Nevertheless, Justice William O. Douglas argued that the court could infer the individual right to privacy from the “penumbras” of rights guaranteed in the First and Fourteenth Amendments, among others. The penumbras were “formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.” The two justices who dissented in the case contended that since the right to privacy was not stated in the Constitution, it was beyond the power of the court to enforce such a right. While the immediate effects of Griswold v. Connecticut were somewhat limited, the decision was a critical precedent for future decisions related to morality, sexuality, and privacy. Most notably, the decision was foundational for Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision legalizing abortion.

Many of the most transformative judicial decisions of the 1950s and 1960s indicated a growing concern by the court to interpret the Constitution as protecting minority groups from unfair practices or laws supported by majority groups. Along these lines some of the court’s most controversial rulings of the early 1960s had to do with religion in public schools. In most parts of the country, there was broad-based support for religious teaching or Bible reading in schools. But small groups of dissenters argued that official promotion of religion violated their consciences and represented an “establishment of religion.” The First Amendment had forbidden Congress from making any law respecting an establishment, but the courts increasingly applied such restrictions on Congress to states and towns. (The legal principle of expanding the applications of the amendment is called the “incorporation” of the First Amendment’s guarantees.) At the time of the American founding, many states still had official tax-supported denominations, which was the original meaning of the term “establishment.” Now courts decreed that even generic public religious expressions represented unconstitutional breaches of the “wall of separation” between church and state, a phrase taken from an 1802 letter written by Thomas Jefferson. The courts gave less weight in these types of cases to the First Amendment’s guarantee of “free exercise of religion.”

One of the Supreme Court’s major decisions about religion in schools was Engel v. Vitale (1962), in which plaintiffs objected to a theistic (not explicitly Christian) school-day prayer sanctioned by public schools in New York. Although students could leave the room during the prayer or decline to participate, the court ruled that these protections were insufficient and that the prayer represented an establishment of religion. The decision did not intend to stifle student-initiated prayers or the silent prayers of any individuals at public schools. But the court determined that state officials could not compose prayers for students to recite.

The court followed up Engel with Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), which prohibited officially sanctioned Bible reading in public schools. Before Abington, it was common for American schools to have Bible readings as part of regular school-day activities. The majority of American states permitted such readings, and thirteen states required them. Typically teachers would read Bible passages without comment to avoid sectarian controversy. But since the Bible used was primarily the King James Version, groups that did not use or accept the authority of the King James, including Catholics, Jews, and others, sometimes felt excluded. At Abington High School in Pennsylvania, teachers actually used other holy texts besides the King James, including Catholic and Jewish versions of the Scriptures. But the Schempp family, who were Unitarians, protested that the Bible reading itself violated their consciences and represented an establishment of religion. (In a related case in Baltimore, an atheist family objected to Bible reading and a recitation of the Lord’s Prayer.) The practice of official Bible readings in schools disappeared in most areas of the country after Abington School District, although courts have given latitude for student-led Bible clubs. Courts have also permitted some Bible-oriented school content as long as it approaches the Scriptures as history or literature, not as devotional material.

Many Christians lamented the effects of Engel and especially of Abington School District. Some said they could accept Engel’s ban on generically theistic prayer. Prohibiting Bible reading seemed like a severer blow. The president of the National Association of Evangelicals said Abington was helping create an “atmosphere of hostility to religion” in the schools. The government was supposed to be neutral between religion and irreligion, but the decision opened “the door for the full establishment of secularism as a negative form of religion.” Numerous Catholic leaders also criticized the rulings in spite of some reservations Catholics once had about schools reading from Protestant Bibles. The Catholic archbishop of New York said the Supreme Court’s decisions had struck “at the heart of the Godly tradition in which America’s children have for so long been raised.” Jewish and mainline denominational leaders generally supported the decisions. Many Southern Baptists, due to their denomination’s historic antipathy toward any state collusion with religion, were content with the rulings, especially Engel. Some African American pastors regretted the court’s actions in Engel and Abington, although Martin Luther King Jr. thought the prayer decision was correct. “Who is to determine what prayer is spoken, and by whom?” he asked. Public schools were not in the best position to decide, he said.

Johnson and Vietnam

Johnson, Congress, and the Supreme Court initiated a host of transformative changes at home in America in the mid-1960s. Foreign policy, however, would prove Johnson’s undoing. Naval altercations between US and communist North Vietnamese forces in August 1964 led Johnson to propose the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, under which Congress authorized the president “to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression” in the region. Although critics charged that Johnson had exaggerated the nature of the August 1964 clash in Vietnam, Congress overwhelmingly approved the resolution. It effectively allowed Johnson to take America to war in Vietnam without a formal declaration of war. In the short term the Gulf of Tonkin resolution undercut Barry Goldwater’s assertion that the Democrats were weak on communism, boosting Johnson’s landslide victory in the 1964 election.

Although Johnson was aware of the perils of sending large numbers of American troops into Vietnam, he began to escalate the American presence there in mid-1965. He hoped to save the floundering South Vietnamese government from the communist Viet Cong rebels, sending 50,000 Americans into South Vietnam and indicating he would send more if necessary. By the end of 1967, the number of US troops committed to Vietnam had expanded to 500,000. The Americans had massive advantages over the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong, especially in air power. The American army dumped copious amounts of the defoliating chemical Agent Orange and the firebombing fuel napalm to clear out communists’ cover and deprive them of food supplies. (Agent Orange was toxic and left many American soldiers and Vietnamese people with chronic health problems.) But years of bombardment of the communist forces availed little. The communist rebels were masters of guerrilla warfare and ambush attacks.

The American army in Vietnam was young. The average age of the GIs in Vietnam was only nineteen. Most of the American soldiers came from poor or working-class families, and Hispanics and African Americans were disproportionately represented in the army. Men who were in college could typically get student deferments, while those who went to work after high school often got drafted and sent to Vietnam. Future president Donald Trump, for example, got four student deferments and one medical exemption (for bone spurs in his feet). American soldiers felt pride in their call to serve. But many also became disenchanted with the lack of clear objectives in the war and suffered under the constant threat of land mines and Viet Cong ambushes. Relations between the South Vietnamese and American forces in the field were often tense, as Americans suspected that South Vietnamese “allies” were actually communist sympathizers.

American commanders too often measured success by the number of Vietnamese killed, or what became known as the “body count.” This tempted soldiers to kill any Vietnamese person whether they were sure of their allegiances. If they encountered a Vietnamese person in the jungle at night, US soldiers assumed he or she was Viet Cong. One soldier expressed the frustration of many when he asked, “What am I doing here? We don’t take any land. We don’t give it back. We just mutilate bodies. What the f*** am I doing here?” Both sides committed atrocities against the other, culminating in episodes such as the US massacre of hundreds of unarmed Vietnamese civilians at My Lai in 1968.

Figure 26.5. A soldier of the First Infantry Division motions to a woman refugee to keep her children’s heads down during a fight with Viet Cong who had attempted to ambush the unit during a move through an area crisscrossed with bamboo hedgerows, January 16, 1966. Photograph by the Department of Defense.

Protests at Home

The stalemate in Vietnam gave a focal point for unrest in America about concerns that erupted among students and other activists. (Ironically, many of these protesting students remained home from the war because of student deferments.) Protesters held anti-Vietnam rallies on campuses across the country and staged assemblies at the Pentagon and other military sites. In 1968, activists took control of a number of buildings at New York’s Columbia University, shutting much of the school down for a week before police could regain control. The unrest fueled the expansion of a new “hippie” culture, rooted in the older “Beat” movement that had emerged in the 1950s. Hippie culture glamorized New Age religion and the use of drugs like marijuana and LSD, and it inspired new genres of popular rock and folk music.

Perhaps the signature moment of the hippie movement came at the Woodstock music festival in New York in 1969, advertised as “An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music.” Some 400,000 people attended the Woodstock festival, hearing round-the-clock musical performances from headliner acts such as Joan Baez, the Grateful Dead, and the African American guitar impresario Jimi Hendrix. Many Americans found the hippie and protest culture distasteful and unpatriotic. The idealization of America’s traditional small-town values was also expressed in popular music, such as in Merle Haggard’s 1969 country music hit “Okie from Muskogee.” That anthem opened with Haggard explaining that people in small-town Oklahoma didn’t smoke marijuana or use LSD. “We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street,” he sang, “’Cause we like livin’ right, and being free.” As president, Richard Nixon used the term “silent majority” to describe those average Americans who did not join the protests or the countercultural hippie movement.

Frustrations over Vietnam and the slow progress of social change energized a radical and sometimes violent phase of the civil rights movement. Some blacks in northern and western cities felt left out of the movement, which had focused so much on the racist practices of southern cities. Blacks and other minorities outside the South suffered under many of the same disadvantages in terms of economic opportunity, residential segregation, and tensions with police. Martin Luther King Jr. tried to take his movement to Chicago in 1965 and 1966 but found it almost impossible to bring about reform in the city’s segregated schools and neighborhoods. Chicago’s segregation tended to depend on local practices and habits rather than overtly racist laws.

Increasing numbers of blacks adopted the black nationalist philosophy of Malcolm X, calling for violence against whites when necessary. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee came under the leadership of Stokely Carmichael and repudiated its roots in King’s philosophy of nonviolence. Urban riots continued after the violence in Watts in 1965, with forty-three people dying in clashes in Detroit in 1967. Many whites who had not yet joined in the flight to the suburbs gave up on the cities in the aftermath of these riots, speeding up the founding of new white-majority suburban towns, school districts, and churches. “White flight” increasingly left the “inner cities” of America economically impoverished, with disproportionately large African American and Hispanic populations.

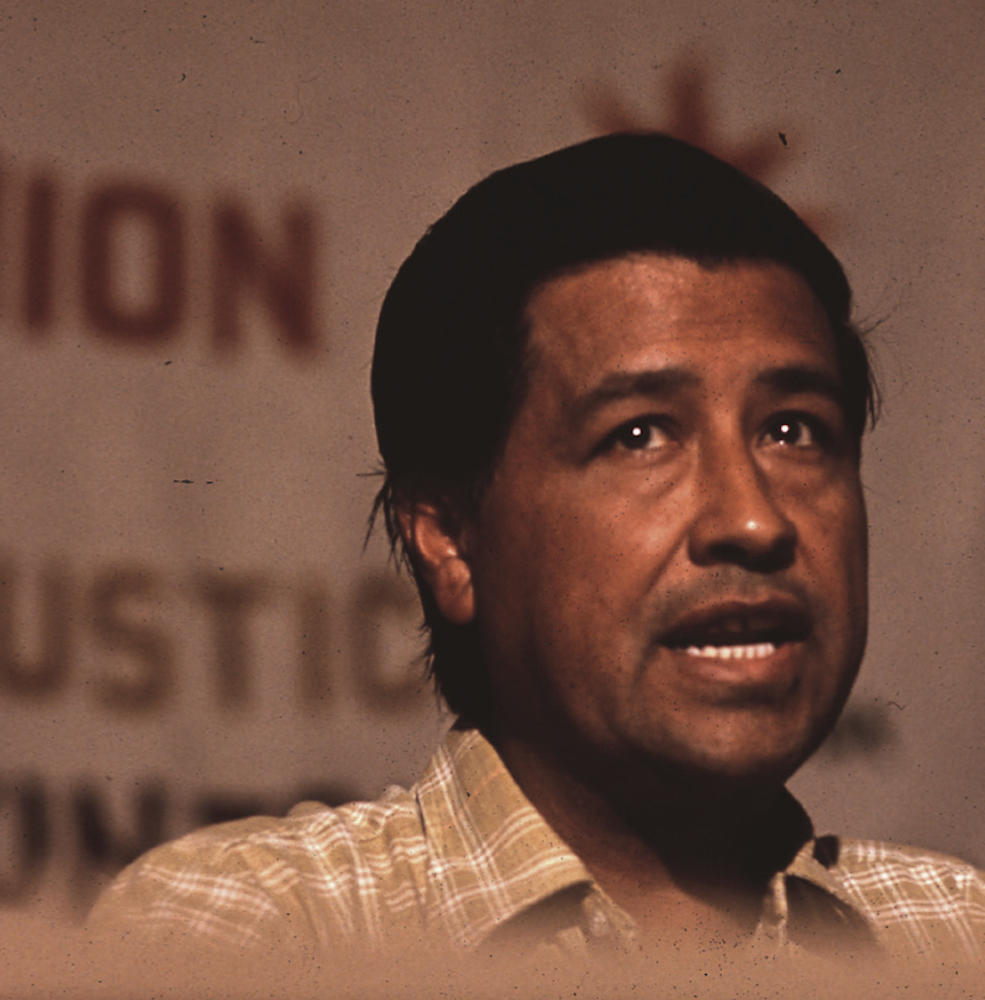

Mexican Americans also became a more politically cohesive force in the 1960s, led especially by farmworker activist César Chávez. Even though Chávez was a third-generation US citizen, Chávez’s family had endured segregation and discrimination while he was growing up in Arizona and California. In the early 1960s, Chávez quietly organized the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) among California field workers. The soft-spoken Chávez was an appealing figure to many because he did not seem like a radical. He wanted to enlist the help of Catholic churches, which held such a dominant presence in Hispanic communities. Chávez asked for the presence of the church and its leaders “with us, beside us, as Christ among us.”

Figure 26.6. César Chávez, Migrant Workers Union Leader, July 1972, by Cornelius M. Keyes.

In 1965, Chávez organized a boycott against grape producers to force them to recognize the NFWA. Although many workers suffered terrible financial hardship for their role in the union, Chávez and the NFWA finally broke through to a settlement with the grape producers in 1970. Poverty and language barriers had made Mexicans among the least unionized workers before the 1960s, but Chávez helped consolidate a new “Chicano” political and social identity. Chicano high school and college students began to demand representation of Hispanic figures in literature and history courses. Others insisted that schools accommodate Spanish-speaking elementary school students and that school districts work to hire more Hispanic teachers.

The 1960s helped spawn a reinvigorated women’s movement as well. Books such as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) detailed the dissatisfaction and even loathing some women felt for the conventional roles of wife, mother, and homemaker. Friedan shockingly claimed that the middle-class women “who ‘adjust’ as housewives, who grow up wanting to be ‘just a housewife,’ are in as much danger as the millions who walked to their own death in the concentration camps” of Nazi Germany. Many American women and men, of course, rejected such characterizations of American domestic life and traditional women’s roles. Evangelical women such as Anita Bryant and Beverly LaHaye defended distinct male and female roles in marriage and family. Traditionalists insisted that women’s desire for professional careers undermined God’s plan for most women, which was to be mothers. Ella May Miller’s I Am a Woman (1967), for example, said that “woman’s primary role and greatest contribution is that of being a mother.”

American women who did seek professional careers often encountered unequal pay or barriers to being hired and promoted because of their sex. Legislation sought to address these issues with the 1963 Equal Pay Act and a provision in the Civil Rights Act (1964) that prohibited employment discrimination on the basis of one’s sex. In reality these congressional measures were difficult to enforce without aggressive legal action. This difficulty was part of the inspiration for Friedan and other women to found the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966. NOW positioned themselves as a civil rights organization and demanded employment equality as well as the legalization of contraception and abortion. Most states had laws restricting abortion. But liberal women’s activists believed women and their doctors should have the right to “control their reproductive lives,” including the right to terminate an unborn infant’s life, as part of women’s broader access to contraception.

1968: A Year of Turmoil

The year 1968 opened with the Viet Cong launching broad-based attacks on the South Vietnamese. The attacks began at Tet, the Buddhist new year, so the Viet Cong campaign became known as the Tet Offensive. Although the American and South Vietnamese forces were able to repulse most of the Viet Cong’s assaults, the Tet Offensive brought American morale to a new low. Following the Tet Offensive, polling showed that only 32 percent of Americans approved of Johnson’s handling of the conflict in Vietnam. The conflict in Vietnam showed no signs of coming to a conclusion soon, contrary to what some leaders had told Americans. Popular CBS anchor Walter Cronkite, viewed by many Americans as a trusted and impartial observer, reported from Vietnam in February 1968 and suggested it was time for the United States to accept that the Vietnam War was unwinnable. When it appeared that Johnson might face major challenges in the Democratic primaries for president in 1968, Johnson made two major decisions. First, he decided to scale back his bombing campaigns in Vietnam and to approach the North Vietnamese about peace negotiations. Then he announced that he would not seek reelection as president.

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was killed by an assassin in Memphis, Tennessee, where King had gone to lead protests on behalf of poorly paid sanitation workers. In his last public sermon the day before his death, King spoke almost prophetically about what was to come. “We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long time. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now, I just want to do God’s will.”13 King was thirty-nine. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan would sign an act making King’s birthday a national holiday.

After Johnson decided not to run for president again, President Kennedy’s brother Robert, a US senator, emerged as one of the leading candidates for the Democratic nomination. Kennedy won the California Democratic presidential primary on June 5, but that night he was shot and killed by a deranged gunman named Sirhan Sirhan. Democrats were bitterly divided over the political contest that followed between the peace candidate, Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, and Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey (also from Minnesota). Humphrey supported Johnson’s measured approach to resolving the war in Vietnam. Humphrey won the Democratic Party nomination. But the Democrats’ national convention in Chicago in 1968 was marred by anti-Vietnam and anti-Humphrey protests, including televised clashes between protestors and police. Alabama’s former governor George Wallace, a firm proponent of segregation, also announced an independent bid for the presidency, once again threatening the Democrats’ traditional dominance of the Deep South.

The Republicans, by contrast, easily unified around the candidacy of Richard Nixon in 1968. Nixon had lost the presidential election of 1960 but had worked to bolster his national support among Republicans in the intervening years. Nixon indicated that he planned to bring the war to an end as well, but he offered few specifics about what approach he would take. Johnson’s decision in October 1968 to stop the bombing in North Vietnam did help Humphrey consolidate the support of antiwar Democrats, but in the end Nixon won the Electoral College handily. The popular margin was razor-thin, however, with Nixon winning 31.8 million votes to Humphrey’s 31.2 million. Wallace won five Deep South states and almost 10 million votes nationally. Nixon dominated the upper South, the West, and much of the Midwest. His election signaled the end of the era of expanding domestic government programs that had run from the New Deal to the Great Society. Nixon’s “silent majority” looked to him to restore order after the strategic disaster of Vietnam and to soothe the tumult of radicalization and protests the war had inspired. Some even hoped Nixon might restore the national hope and optimism that had prevailed at the time of John Kennedy’s inauguration, just eight years earlier. But Vietnam and presidential scandal would mire the nation even deeper in cultural “malaise.”

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Garcia, Matthew. From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Hale, Jon M. The Freedom Schools: Student Activists in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Herring, George C. America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950–1975. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2013.

Howard-Pitney, David, ed. Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and the Civil Rights Struggle of the 1950s and 1960s: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004.

Marsh, Charles. God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Patterson, James T. Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974. Repr. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Schäfer, Axel, ed. American Evangelicals and the 1960s. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013.

Williams, Daniel K. Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement before Roe v. Wade. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Young, Neil J. We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

11 Reprinted by arrangement with The Heirs to the Estate of Martin Luther King Jr., c/o Writers House as agent for the proprietor New York, NY. Copyright © 1963 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. © renewed 1991 Coretta Scott King.

12 “Fannie Lou Hamer’s Powerful Testimony | Freedom Summer,” YouTube video, 3:40, June 23, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=07PwNVCZCcY.

13 Reprinted by arrangement with The Heirs to the Estate of Martin Luther King Jr., c/o Writers House as agent for the proprietor New York, NY. Copyright © 1968 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. © renewed 1996 Coretta Scott King.