28

Reagan’s America

Since the colonial era, America had been part of a global economy—just think of the British-shipped tea, grown in China and India, that had helped cause the American Revolution. Or how the South dominated the world’s trade in cotton before the Civil War. But the 1980s marked a distinct escalation in globalization for America and the world. The American automobile market, once dominated by Detroit-based companies such as Ford and Chevrolet, had already seen a growing presence of foreign competitors, including Volkswagen (Germany), by the 1970s. In the 1980s, Japanese-based Toyota and Honda threatened to displace the Detroit carmakers at the top of the industry.

“Buy American” sentiment was common during the 1980s, as American automakers struggled to keep up with the increasingly popular Japanese models. The notorious assault and killing of Chinese immigrant Vincent Chin in Detroit in 1982 was said to have been provoked by resentment against growing Asian power in the auto industry. One of Chin’s assailants was a supervisor at a Chrysler plant. American politicians accused the Japanese of unfair trade practices, but Japanese companies blunted those charges by setting up more Japanese-owned factories in the United States. By 1988, more than 300,000 American citizens worked for Japanese businesses in US-based offices and factories. In a watershed moment in 1989, the Honda Accord became the best-selling car in America, the first foreign model to achieve that rank.

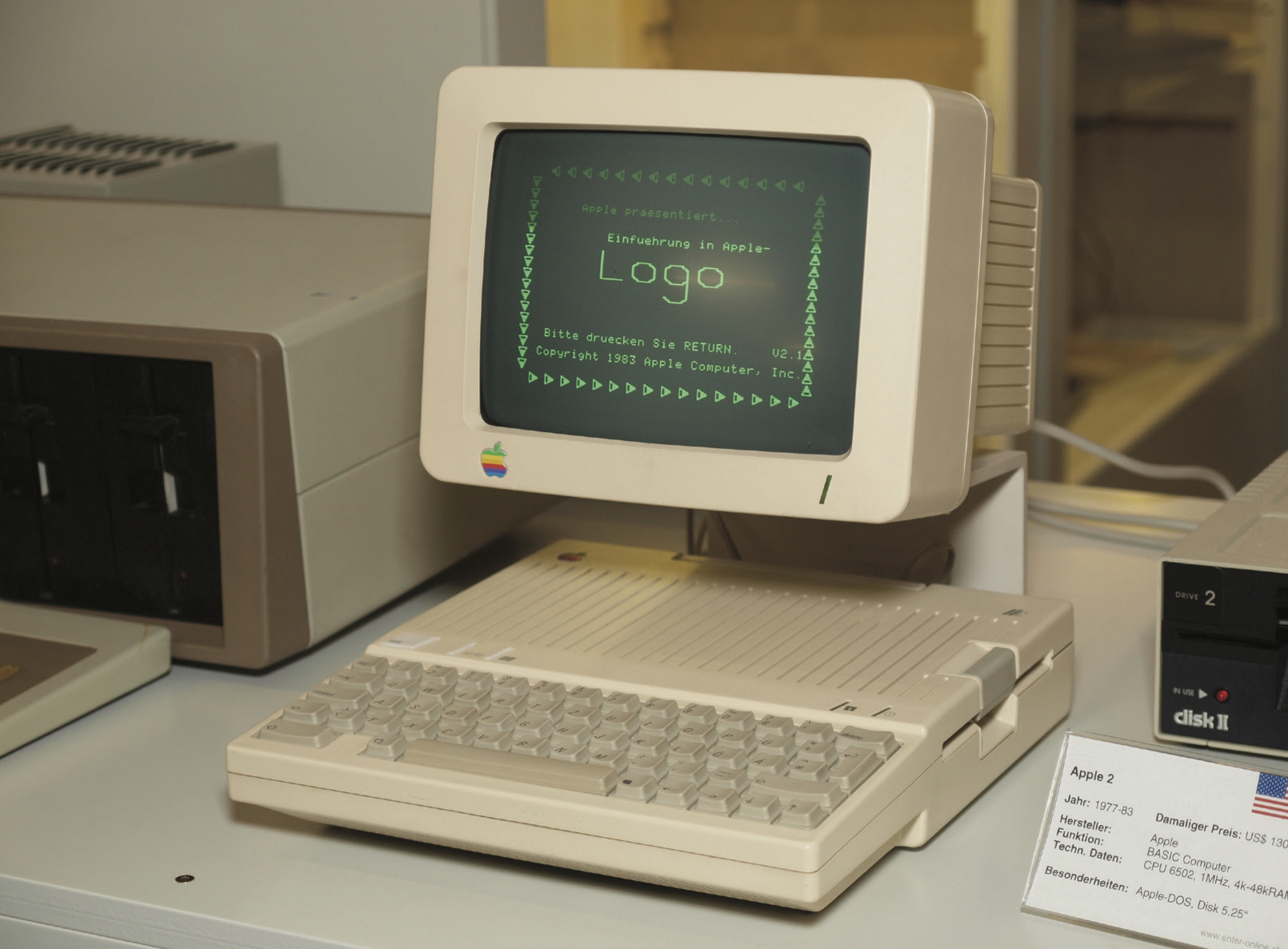

In technological fields the United States was also bringing products to market that would change the global economy as well as everyday life around the world. The Cold War had accelerated the use of computers in weapons and space flight systems, but in “Silicon Valley” in California, some entrepreneurs dreamed of introducing personal computers to the consumer market. Among these were Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, who founded Apple Computer in 1976, and in 1977 they introduced the Apple II computer. Unlike previous home computer kits, which only hard-core electronics enthusiasts could build, the Apple II was designed to be accessible to anyone. About 2 million Apple IIs eventually sold. In 1981, International Business Machines entered the market with the IBM PC, which eventually became the most common computer model used in American businesses. IBM PCs and their numerous “clones” would generally use the operating system made dominant by Microsoft, founded by Bill Gates and Paul Allen in 1975. Later, Steve Jobs helped design the Apple Macintosh, or “Mac,” which put Apple computers into even more homes and schools.

Jobs left Apple in 1985 but would return as CEO in 1997 and went on to play a major role in the development of the smartphone, a combination of computer and cellular phone technology. Older phone technologies had depended on landlines, but the cell phone concept allowed users to take their phones with them wherever they went. Wireless phones were first approved for commercial use in the United States in 1982, but their early functionality was low and expense was high. International companies such as Finland’s Nokia produced affordable cell phones in the 1990s. In the 2000s, a Canadian company successfully introduced the BlackBerry, one of the first smartphones, with a small physical keyboard on the phone for email and text messaging.

Figure 28.1. Apple IIc, 2012.

In 2007, Jobs and Apple introduced the iPhone, with touch screen technology and a suite of “apps” that grew exponentially over time.15 The iPhone and related technologies dramatically transformed the global personal electronics and phone markets and turned Apple into the largest company in the world. Parts of the iPhone were designed in places from the United States to Germany and Japan, but for its first ten years, most of the phones were manufactured in China. Globalization meant alluring products at affordable prices, but the associated decline of America’s manufacturing sector presented one of the most difficult economic and political problems of the post-1960s era in American history.

Reagan’s Presidency

Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, presiding over a nation in considerable economic distress. Reagan believed the key to revitalization was supply-side economics, or “Reaganomics.” This philosophy included the idea that a booming private sector, not government spending, was essential to true economic health. Reagan helped push through tax cuts as well as tens of billions of dollars in government spending cuts in areas such as social welfare, job training, and transportation. Reagan sought to encourage more private-sector competition through actions such as the 1982 settlement that resulted in the breakup of the American Telephone and Telegraph company and its monopoly over much of the telecommunications business. Although the nation went into a deep recession in 1981–82 and the federal budget deficit went up sharply, the rest of Reagan’s tenure was generally marked by economic growth, increasing employment, and reduced inflation.

Reagan’s presidency had barely gotten started when he was nearly assassinated. In March 1981, a mentally unstable man named John Hinckley Jr. opened fire on Reagan outside a Washington, DC, hotel. Several in Reagan’s entourage were wounded, including Reagan himself, who took a shot to his left lung. Reagan was bleeding badly and was saved only by a two-hour operation. Ironically the attempt on his life made Reagan more popular than ever, as he projected courage and good cheer throughout the ordeal. He parlayed his injuries into political capital that helped him pass his budget and tax cuts. As he lobbied Congress, Reagan successfully wooed conservative southern Democrats, whose votes he needed to pass legislation in the House of Representatives.

The high drama of Reagan’s first year continued in August 1981, as he faced down the air traffic controllers’ union, which threatened to strike in order to obtain better hours and pay. During his film career, Reagan had served a number of terms as the head of the actors’ union, the Screen Actors Guild. Union workers had typically voted Democratic, but many of them had warmed to Reagan’s candidacy in 1980. But in his standoff with the air traffic controllers, he showed a steely resolve that delighted many business leaders and conservatives and dismayed union representatives. Believing the controllers’ walkout would cripple America’s transportation system and freeze many business activities, Reagan also noted that as federal employees, the air traffic controllers could not legally go on strike. The president gave the controllers an ultimatum: return to work within two days or be fired. When only a minority of controllers returned to work by the deadline, he fired the rest, which was more than 11,000 workers. The action wrecked the controllers’ union and put the rest of America’s unions on notice that they should not trifle with Reagan. The number of strikes afterwards dropped to some of the lowest levels since the beginning of the American labor movement.

Although Reagan wanted to curtail domestic government spending, he wanted to increase military spending. He felt that America had become paralyzed by the failure in Vietnam and that it still needed to confront the threat of Soviet communism with robust military power. The Republicans called their military philosophy “peace through strength,” or the idea that only by maintaining a formidable military could America challenge and forestall the aggressive acts of nations opposed to US interests. Critics argued that military buildup only made war more likely. When Reagan won congressional approval for a new class of nuclear weapons, hundreds of thousands of protestors joined a rally in New York’s Central Park in 1982, calling for a freeze in the development of nuclear arms.

Reagan’s Foreign Policy

Reagan embodied the Cold War conviction that Soviet power represented a grave threat to the United States and that the Soviets were looking to expand their sphere of influence around the world in countries such as Afghanistan, Nicaragua, and the West African nation of Angola. Addressing a meeting of evangelical Christian leaders in 1983, Reagan called the Soviet Union an “evil empire” and the “focus of evil in the modern world.” He also positioned more missiles at US outposts in Europe, countering the Soviets’ missile installations that threatened America’s European allies in NATO. Reagan boosted investment and research into the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a futuristic program that would have employed satellite-based laser beams to destroy incoming Soviet missiles. Critics mocked SDI as “Star Wars,” a term derived from the wildly successful space film of 1977. But without an effective missile defense system, the Reagan administration contended, the United States would simply have to accept the nightmare scenario of a nuclear attack leading to the mutually assured destruction of much of America and the Soviet Union.

Reagan’s tough stance toward the Soviet Union helped promote diplomatic breakthroughs with the communist nation in his second term. This was partly due to major changes in Soviet leadership. Longtime American rival Leonid Brezhnev died in 1982. After the quick deaths of two successors to Brezhnev, Mikhail Gorbachev finally became Soviet premier in 1985. The reform-minded Gorbachev would take the USSR into a new era of “glasnost,” or domestic freedoms and openness to the West. Gorbachev feared that his brittle, impoverished nation was going to collapse without serious change. Gorbachev also realized that Reagan’s aggressive military buildup could destroy an already-weakened Russian economy if the Soviets tried to keep up with the Americans’ pace in programs such as SDI.

Negotiations between Gorbachev and Reagan began in 1985, and in 1986 they met at a summit in Reykjavík, Iceland. The summit produced wildly ambitious talks about the Russians and Americans eliminating their entire stockpile of nuclear weapons. No firm deal was struck, though. Reykjavík did set the stage for a significant agreement in Washington in 1987, in which Reagan and Gorbachev agreed to draw down the intermediate-range nuclear missiles the nations had stationed in Europe. The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF Treaty, represented the first time during the Cold War the two sides had agreed to eliminate any nuclear weapons rather than just limit additional ones. Although some critics suggested that Reagan was going soft on communism, the Senate overwhelmingly approved the INF Treaty in 1988.

The INF Treaty left a great deal of unfinished business in US-Soviet relations as well as in the status of communism in Eastern Europe. The full collapse of the Soviet Union and of the communist regimes in Europe would transpire under Reagan’s successor, his vice president, George H. W. Bush. But even as he negotiated with Gorbachev about nuclear weapons, Reagan called for freedom and democracy in the Soviet bloc. One of Reagan’s most famous speeches came in West Berlin in June 1987. Standing in front of the Brandenburg Gate, one of the most recognizable symbols of the wall that divided Berlin into its democratic and communist sections, Reagan called on the Soviet premier to allow freedom to come to East Germany and to reunite Berlin. “Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate!” the president proclaimed. “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Similar to the policy of “containment” from the post–World War II era, the Reagan administration was determined to halt the global spread of Soviet power, especially in the Western Hemisphere. This concern came to a head in Nicaragua, where the revolutionary Sandinista government had received aid from the Carter administration. Reagan and his secretary of state, Alexander Haig, saw the Sandinistas as a conduit for communist power in Central America. The Sandinistas took assistance from the Soviets and Cubans even as they accepted American aid. So Haig stopped payments to the Sandinistas in 1981, which led them to align more firmly with the Soviet bloc. Reagan decided to put US support behind the Nicaraguan “Contras,” anti-communist revolutionaries trying to overthrow the Sandinistas. Congress was reluctant to give direct assistance to the Contras, however, fearing a repeat of the quagmire in Vietnam. The Central Intelligence Agency began funneling covert assistance to the Contras, but the wary Congress banned any unit of the American government from doling out assistance in Central America.

National Security Council (NSC) officials under Reagan remained resolved to help the Contras, however, and concocted secret plans to do so. Among these plans were illicit arms sales to Iran, which they hoped would simultaneously help them gain the release of American hostages in Lebanon and give them a funding source for the Contras. None of these plans worked well, and they came to light during Reagan’s second term in 1986, when an American plane carrying assistance for the Contras was shot down over Nicaragua. When one of the American crew members was captured, the story behind the American arms sales to Iran and funding for the Contras emerged in the international media. John Poindexter, head of the NSC, resigned, and Oliver North, the architect of the funding scheme, was fired. The “Iran-Contra Affair” damaged Reagan’s image, although he successfully deflected charges that he must have known about the elaborate NSC plans.

Turmoil in the Middle East and the threat of terrorism took on a new prominence during Reagan’s first term. Middle Eastern and North African political organizations and government-backed entities increasingly turned to terrorist acts in hopes of wearing down the resolve of enemy states. In spite of widespread antagonism against Israel by its Arab neighbors, Reagan was determined to support Israel in its struggle with the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), then based in Lebanon, launched attacks on Israelis. Israel responded by invading Lebanon in 1982, ultimately driving out the PLO from its haven there. The United States also stationed Marines in Beirut, Lebanon, as part of an international peacekeeping force. In early 1983, terrorists associated with Iran killed sixty-three people in an explosion at the US embassy in Beirut. Terrorists also detonated truck bombs at the Marine barracks in Beirut later in 1983, killing 241 American troops and dozens of French soldiers. A group calling itself “Islamic Jihad” claimed responsibility for the bombings, but the attacks clearly had the support of elements within Iran. Not wishing to start a new war when it was difficult to discern who had ordered the bombings, Reagan took no major actions against Lebanon or Iran in response to the Beirut barracks bombings. In 1984, Reagan withdrew the remaining peacekeeping forces from Lebanon.

Reagan sought to act more decisively against other state sponsors of terrorism when possible. When Israelis and the PLO continued to clash in the PLO’s new haven in Tunisia in 1985, terrorists representing the PLO-affiliated Palestine Liberation Front hijacked an Italian cruise ship, the Achille Lauro. When Israel refused to comply with the terrorists’ demands that they release Palestinian prisoners held in Israel, the terrorists on the ship executed a wheelchair-bound American Jew named Leon Klinghoffer, dumping his body into the sea. Negotiators agreed to give the terrorists safe passage in Egypt, but when the terrorists attempted to leave Egypt by plane, US jets forced the plane to land in Italy. Klinghoffer’s killers were convicted of conspiracy and murder in Italian courts. The Achille Lauro incident badly damaged the PLO’s international reputation. Its chairman, Yasir Arafat, subsequently issued a statement repudiating terrorism. The PLO maintained that it had the right to resist Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory, however. Palestinians would continue to employ tactics Israeli and American officials regarded as terrorism.

The United States repeatedly clashed in the 1980s with Libya and its leader, Muammar Gaddafi, over Libya’s involvement with terrorist attacks. In 1986, Libyan agents blew up a West Berlin disco known to be a popular hangout for US soldiers. The bombing killed three and injured hundreds, and two of the dead were US servicemen. President Reagan ordered retaliatory strikes in Libya, including the bombing of Gaddafi’s home. Gaddafi escaped unharmed, but he claimed the strike had killed his young daughter. Terrorists were also behind the destruction of Pan American Airways flight 103 in 1988, in which 259 passengers and crew died in a midair explosion over Lockerbie, Scotland. Among the dead were 189 Americans. After lengthy investigations, Gaddafi took responsibility for the bombing in 2003.

A Renewal of Conservatism

The 1980s saw a renewal of religious and political conservatism. Reagan helped inspire that renewal, but he was also a product of its success. The cultural changes of the 1960s and ’70s, including the challenges to traditional gender roles and the legalization of abortion, certainly sparked the conservative revitalization. Many conservatives and people of traditional faith saw America as a culture in decline and wanted to return to the great resources of the Judeo-Christian tradition and Western civilization as bulwarks against that decline. The Moral Majority, led by Jerry Falwell, was among the most visible organizations of traditional religion in politics, but the conservative renaissance of the era was far more varied and vital than the Moral Majority.

The conservative trend was not restricted to politics, either. Conservative Catholicism received a generation-defining boost from the papacy of John Paul II, who became pope in 1978. John Paul II (Karol Wojtyla), a native of Poland, was the first non-Italian pope for almost half a millennium. The worldwide influence of Catholicism had been drifting for some time, in spite of modernizing innovations introduced by the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s. But John Paul II’s winsome defense of Catholic orthodox teaching on moral issues such as the value of human life in all of its stages as well as his courageous opposition to communism in Poland and Eastern Europe energized many of the Catholic faithful and drew legions of young people into the church.

Although many Protestants still had concerns about problems in Catholic theology, John Paul II also had longtime connections with evangelical Christians and employed an evangelical style in his ministry. When the pope held a mass at Los Angeles Coliseum, a Hispanic minister named Isaac Canales was struck by the Protestant emphases in the service. “It could’ve been a Billy Graham crusade,” Canales said. He noted that the attendees sang distinctively Protestant hymns and the focus was on “Jesus rather than on the Virgin of Guadalupe.” Catholics in the Americas, including in the United States, continued to lose large numbers of parishioners to Pentecostal and evangelical congregations, however.

Among Protestants, the most remarkable conservative renewal movement of the 1980s and 1990s came in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). Whereas the other large Protestant denominations (including northern Baptists) had gone through the fundamentalist-modernist controversy of the early 1900s, the SBC had passed through that period fairly untroubled by arguments over social issues or theological innovations. This was partly because of the relative isolation of SBC churches within southern culture, which retained a heavy veneer of nominal Christian commitment into the 1970s. Official agencies of the SBC showed signs of cultural liberalism, however, and were slow to take a stand against Roe v. Wade and the legalization of abortion. Even as late as 1979, the SBC could not garner enough support to pass a resolution calling for a pro-life constitutional amendment. But that year theological conservatives began a campaign known as the Conservative Resurgence, during which conservatives would take the reins of the denomination’s top offices and seminaries and marginalize moderate and liberal leaders. The SBC conservatives prioritized uniformity on issues such as abortion, the inerrancy of Scripture, traditional marriage roles, and restricting the senior pastoral office to men alone.

American Baptist (or northern Baptist) churches became formally committed to ordaining women as senior pastors in 1989. The practice had become more common in the SBC as well, especially during the 1970s and the era of the Equal Rights Amendment. But conservatives insisted the Bible taught that God intended for men to occupy positions of spiritual leadership in the church and in families. The energized conservative movement in the SBC passed a resolution against women’s ordination at the denomination’s annual meeting in 1984, precipitating a mass showdown at the 1985 convention in Dallas for control of the SBC. Forty-five thousand Southern Baptist messengers attended the meeting, far beyond the previous attendance record. The moderates’ preferred candidate for convention president was no liberal, but he believed liberals and conservatives could coexist in the governing boards and seminaries. The conservatives insisted there could be no compromise with those who doubted any part of the Bible as the Word of God. Dallas pastor W. A. Criswell predicted that “whether we continue to live or ultimately die lies in our dedication to the infallible Word of God.” When a telegram went public in which Billy Graham (a longtime member of Criswell’s church) seemed to endorse the traditionalist candidate, Pastor Charles Stanley of Atlanta, conservatives reelected Stanley as SBC president with 55 percent of the vote.

The 1985 convention represented the beginning of the end for the liberal-to-moderate faction in the SBC. Conservatives ensured that new and existing faculty members at SBC seminaries affirmed the inerrancy of the Bible, that they affirmed the historicity of events such as Adam’s and Eve’s immediate creation by God, and that they did not present the miraculous events of the Scripture as myths or metaphors. Investigations suggested a significant presence of theologically liberal professors at half or more of the SBC seminaries. The flagship Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, became the biggest flashpoint for conservatives trying to restore full theological orthodoxy at all SBC institutions. The appointment of Albert Mohler as president of Southern Seminary in 1993 led to a nearly wholesale turnover in faculty and administration. Mohler’s presidency, and similar developments at other SBC schools, ensured far more theological and cultural uniformity and conservatism within the SBC.

Cultural and political issues such as abortion brought together Christians from across traditional denominational lines. Jerry Falwell presented the Moral Majority as an ecumenical organization, although it was dominated by evangelical Protestants and drew limited support from groups such as Roman Catholics. Nevertheless, traditionalist Protestants, Catholics, and even Jews often found themselves having more in common culturally with one another than with liberals in their own denomination or faith tradition. This sense of conservative commonality led to the founding of publications such as First Things (1990) by Father Richard John Neuhaus, a convert to Roman Catholicism and former Lutheran minister. First Things offered a platform to an extraordinary range of Christian and Jewish academics and clergy, with common concern for a traditionalist cultural witness, the Judeo-Christian intellectual tradition, and the primacy of theological orthodoxy. First Things coordinated the “Evangelicals and Catholics Together” statement of 1994, which admitted enduring differences between the two traditions yet affirmed a common commitment to basic principles of Christian theology, religious liberty, and the right to life. Neuhaus and the evangelical leader Charles Colson of Prison Fellowship were the key organizers and signatories of the document.16

The 1980s also saw a renewal of conservative thought in legal circles. Many judges and law professors felt that American courts had become shadow legislatures, imposing their opinions and preferences on American society rather than rigorously adhering to the law and the Constitution. The Federalist Society, one of the most influential conservative legal associations in America, began in 1982 with a mission to encourage judicial restraint and the principle that it is the “duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be.” President Reagan’s Supreme Court nominees had a mixed record on judicial restraint and cultural issues such as abortion, however. Reagan’s first appointee, Sandra Day O’Connor, was the first woman member of the Supreme Court. But religious conservatives were dismayed by her selection as she lacked clear pro-life credentials, and she went on to become a reliable vote in favor of abortion rights. In 1986, Reagan named conservative William Rehnquist, a Nixon appointee, to replace the retiring chief justice Warren Burger. Reagan tried to appoint the formidable conservative judge Robert Bork in 1987, but the Senate rejected Bork’s nomination after contentious confirmation hearings. Reagan then nominated Anthony Kennedy, who represented the court’s “swing vote” between liberal and conservative members for three decades before his retirement in 2018. On cultural issues such as abortion and sexuality, Kennedy typically adhered to the liberal activist position.

Ideologically, Reagan’s most significant Supreme Court appointment was Antonin Scalia, who joined the court in 1986. Scalia served for thirty years on the court until his death in 2016. During that time he became the most influential conservative legal voice in the nation. Scalia explained that the proper way of “interpreting the Constitution is to begin with the text, and to give that text the meaning that it bore when it was adopted by the people.” Scalia became best known for his biting dissents in cases such as Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the most important abortion decision since Roe v. Wade. In it the Court affirmed the “essential holding” in Roe that access to abortion was a constitutional right. Rejecting this idea, Scalia suggested that the Supreme Court’s liberal majority was “systematically eliminating checks upon its own power.” Characterizing the majority opinion as “standardless” and a “verbal shell game,” Scalia insisted that what really motivated the justices were “raw judicial policy choices concerning what is ‘appropriate’ abortion legislation.”

Figure 28.2. Antonin Scalia, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, August 11, 2005.

Society and Culture in 1980s America

Conservatives pointed to what they saw as the suffering and turmoil the cultural changes of the 1960s had unleashed. In addition to ongoing evidence of the breakdown of traditional family structures, the appearance of a newly public gay rights movement was followed by the AIDS epidemic. In the early 1980s, the American medical community diagnosed a deadly sickness called “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” (AIDS), which left patients vulnerable to infections and certain types of cancer. AIDS could be transmitted through a variety of means, including blood transfusions, needle sharing in drug use, and most any type of sexual activity. But in the 1980s, the most common victims were men engaging in homosexual acts. By 1990, some 100,000 people had died in America due to AIDS. Some Christians speculated that AIDS was divine wrath against homosexuals. But when Magic Johnson of the Los Angeles Lakers announced that he had been diagnosed with AIDS in 1991, it changed public perception of the disease. Johnson, one of the greatest basketball stars of the 1980s, said he had never engaged in homosexual acts. He admitted that he likely contracted the disease from one of a number of sexual encounters he’d had with women other than his wife. Treatment for AIDS improved significantly over time, meaning that people like Johnson with access to good care could live active lives for many years after an AIDS diagnosis. A cure for the disease remained elusive, however.

African Americans had made a great deal of legal progress by the time Ronald Reagan came into office. But social and economic problems remained intractable, and informal kinds of discrimination against blacks and other ethnic minorities have remained common into the present day. Certain blacks began ascending to positions of major political power: New York City and Chicago both elected their first African American mayors during the 1980s. The Reverend Jesse Jackson won several Democratic primaries for president in 1984 before losing the nomination to Walter Mondale. But for impoverished African Americans, the prospects for advancement looked bleaker than ever in the 1980s. The disintegration of African American families continued, and the majority of poor black children lived in families headed by a single mother.

The aspirations and frustrations endemic to black culture helped produce rap music, one of the most distinctive musical forms in modern America. Rap was part of a broader hip-hop culture of art, music, and dance, first emerging from African American communities in New York City in the 1970s. Rap featured rhythmic speech over musical tracks. The first commercially successful rap song was the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” (1979). Rap musicians routinely focused on edgy themes of sex and violence, drawing criticism even from certain black leaders. With relentless profanity and misogynist talk about women, N.W.A.’s 1988 album, Straight Outta Compton, raged against police violence toward blacks and represented the “gangsta” culture of south-central Los Angeles.

African Americans maintained a strong position in mainstream pop music too. Michael Jackson, the son of working-class African American parents from Gary, Indiana, became the most popular pop singer of the 1980s. Tens of millions of listeners worldwide bought Michael Jackson’s 1983 album, Thriller, making it one of the best-selling American albums and best-selling albums globally of all time. The cable television station MTV, launched in 1981, greatly facilitated Jackson’s ascent as one of the country’s most popular singers. Jackson’s popularity and charitable work earned him a visit to the Reagan White House in 1984. With the rise of MTV, video became just as essential to a musician’s success as audio. The advent of cable television also signaled a new proliferation of media outlets, which would slowly challenge the dominance of the major television networks ABC, NBC, and CBS. The cable channels offered increasingly specialized programming as well. The all-sports network ESPN, for example, debuted on cable television in 1979.

Televised sports had taken on their contemporary format by the 1970s, pioneered by shows such as ABC’s hugely successful Monday Night Football, which started in 1970. With flamboyant announcers, slow-motion replays, and multiple cameras, Monday Night Football turned football watching at home into an entertainment event. Televised football now had appeal beyond hard-core fans and served as a revenue-generating event on its own, not just as an enticement to get people to pay to go to games. Sunday afternoon NFL games followed suit, all leading up to the season-ending ratings bonanza of the Super Bowl. By the mid-2010s, the Super Bowl was routinely drawing an average television audience of well over 100 million people. Many sporting events retained massive in-stadium attendance numbers too, with devoted fans showing up to watch sports from NASCAR auto racing to college football. Football games at schools such as Michigan, Penn State, and Tennessee routinely drew more than 100,000 fans.

Some combat-themed sports chose to adopt “pay-per-view” instead of broadcast television, requiring fans to pay to get direct access to live events. One of the first major boxing matches to be distributed as a pay-per-view event was the 1975 “Thrilla in Manila” fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. By the 1980s, headline boxing matches were routinely available only by pay-per-view. The best fights still generated enormous revenue, but boxing faded as a dominant national sport because it only reached a niche audience willing to pay to see top-billed events. Professional wrestling, led by the World Wrestling Federation (later World Wrestling Entertainment, or WWE), also pioneered the televising of arena events, bringing wrestling out of its former setting of small television studios. But the WWE still reserved their top matches for pay-per-view. “Wrestlemania” became the WWE’s preeminent annual event, and in the 1980s Hulk Hogan became the WWE’s top-billing star and the most recognizable wrestler in the world. Hogan headlined the early Wrestlemanias, including his match against André the Giant at Wrestlemania III, held in Detroit in 1987. That event showed that pro wrestling could produce both huge ticket and pay-per-view sales. The paid attendance at the Pontiac Silverdome in 1987 was more than 93,000 and the pay-per-view revenue exceeded $10 million, which was a pay-per-view record at the time. Wrestlemania has remained popular, with the 2016 attendance at “Wrestlemania 32” exceeding 100,000 people.

Perhaps the most celebrated athlete of the 1980s and 1990s was basketball’s Michael Jordan, who paralleled Michael Jackson’s celebrity in music. After growing up in Wilmington, North Carolina, Jordan starred for the University of North Carolina before joining the National Basketball Association’s Chicago Bulls. Jordan’s spectacular athleticism made him a fan favorite even before the Bulls began routinely winning NBA championships in the early 1990s. Jordan would show the lucrative potential for basketball players promoting sporting goods when he signed a major endorsement deal with the shoe company Nike in 1984. It was an agreement that would result in phenomenal profits for Jordan, Nike, and the NBA. Nike developed the “Air Jordan” line of shoes, marketed most effectively by the mid-1980s commercials directed by and starring the movie director Spike Lee. Lee’s character Mars Blackmon was determined to find out the secret of Jordan’s basketball talent, concluding, “It’s gotta be the shoes!”17 Jordan went on to become one of the wealthiest African Americans in the country, at a net worth of more than $1 billion.

Hispanic Americans also found success in sports, especially in baseball, which was popular in many countries throughout the Americas. Hispanic baseball greats included the Panamanian-born Rod Carew and the Puerto Rican Roberto Clemente, who played his whole career for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Clemente was the first Latin American baseball player elected to the sport’s national Hall of Fame. Boston Red Sox great Ted Williams grew up in California with a Mexican mother, but he did not emphasize that part of his heritage. Latin America has produced legions of soccer stars, but those players have often gravitated toward Europe’s more lucrative professional soccer leagues. Soccer has become a popular sport to play in the United States, but it has not been as central to the American sports industry as football or other pastimes.

Hispanics and Immigration

The growing Hispanic presence in sports such as baseball suggested their growing numbers in American society generally. Hispanics continued to come to the United States in large numbers, with distinctive pockets of ethnic Latino communities emerging across the nation—Puerto Ricans and Dominicans in New York City, Cubans and Puerto Ricans in south Florida, and Mexicans in regions of the Southwest from California to Texas. The Hispanic population continued to swell through the 1980s with large numbers of immigrants and a higher birth rate than average American families. The 2000 census revealed that Hispanics had become the nation’s largest ethnic minority group, surpassing African Americans.

In the 1980s, there was growing political concern to do something about the millions of “undocumented” or “illegal” immigrants living in the United States, most of them from Latin America. The 1986 Simpson-Mazzoli Act, or the Immigration Reform and Control Act, sought to impose “comprehensive” immigration reform by giving long-term undocumented immigrants a legal status and by attempting to discourage traffickers who brought illegal immigrants across the US border. Any undocumented immigrant of “good moral character” who had been living in the United States since 1982 could establish a legal residency status by paying a fee and agreeing to learn English. The law resulted in about 2.7 million immigrants receiving “green cards” as permanent US residents. Critics called the program “amnesty,” but it represented the largest legalization of undocumented immigrants in American history and was signed by President Reagan. Millions of other undocumented immigrants were not covered by the Simpson-Mazzoli program, however, so they lingered in uncertainty. Moreover, the law’s enforcement measures, designed to discourage more illegal immigration, did not work well. By the 2010s, the number of illegal immigrants in the US rose to more than 11 million.

Hispanic immigration of any sort was normally fueled by a desire to reunite families or for adult men to earn money for families back home. But immigration could also happen in bursts prompted by political developments in Latin America. One of the most dramatic influxes came during the 1980 Mariel Boatlift from Cuba, which produced a flood of 125,000 Cuban immigrants to Florida in five months. Cuba’s communist dictator, Fidel Castro, had permitted Cubans wishing to leave the island to do so, but the Cuban government also actively sought to remove “subversives” from the island. These could include democratic activists, the mentally ill, homosexuals, and a host of others. Earlier Cuban immigrants to Florida had tended to be light skinned and middle class, while the Mariel immigrants tended to be dark skinned (with more African ancestry) and poor. Miami’s longstanding Cuban population was determined to distinguish themselves from the new marielito population.

Republican Electoral Triumphs

The US economy in 1983–84 was growing again after the early Reagan recession and the malaise of the 1970s. In 1984, Reagan faced Minnesota’s Walter Mondale, who had been Jimmy Carter’s vice president. Although Mondale could count on much of the Democratic base, and he made some inroads in recovering the white working-class vote, he had little chance against the popular Reagan. Reagan’s campaign produced the “Morning in America” TV advertisement, which observers regard as one of the most effective ads in American political history.18 Reagan staked his campaign on the idea that America was better off in 1984 than it had been at the end of Carter’s presidency. Mondale reminded voters that the national debt was rising quickly and honestly admitted that he would support tax increases if he were elected. Mondale named Democratic congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro as his vice-presidential nominee, the first woman candidate on a major party’s presidential ticket in American history.

In November 1984, Reagan won reelection in a landslide over Mondale, taking the Electoral College 525 to 13. Reagan received almost 59 percent of the popular vote. Although Republicans held the majority in the Senate until 1986, Democrats still controlled the House, forcing Reagan to look for bipartisan support for his agenda. Democratic soul-searching led some southern Democrats to conclude that the party had swerved too far to the left with the nomination of Mondale and that the party needed to bolster its moderate credentials and appeal to white southerners. This desire resulted in the formation of the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) in 1985. One of the rising stars of the DLC was Arkansas governor Bill Clinton, who would end the Republicans’ streak of presidential victories in 1992.

Reagan’s second term was marked by more struggles, especially because of episodes such as the Iran-Contra Affair. Yet Reagan remained generally popular, not least because of his uncanny ability for rallying Americans (and even people around the world) through his outstanding speeches. This was displayed in Berlin when he called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall.” Most poignantly, Reagan comforted a grieving nation when the space shuttle Challenger exploded just after liftoff on January 28, 1986. The disaster killed all seven crew members, including Christa McAuliffe, a New Hampshire schoolteacher whom NASA had chosen to go on the mission to bring renewed attention to the space program. Many American schoolchildren were watching the launch live. Reagan had been scheduled to give the State of the Union Address that evening, but instead he gave a tribute to the Challenger astronauts. The memorial was composed by Reagan’s speechwriter Peggy Noonan, who wrote a number of the most important speeches of Reagan and George H. W. Bush. After reassuring American schoolchildren, Reagan concluded his address by quoting the poet John Magee. Americans would never forget the Challenger crew, remembering how they “waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.’”

Investigations into the Challenger explosion blamed a faulty fuel tank seal for the explosion. In 2003, the space shuttle Columbia also broke apart on reentry, signaling the beginning of the end of NASA’s shuttle program. In recent years the United States has increasingly depended on private space transportation companies such as SpaceX to perform missions, including resupplying the International Space Station, a joint venture of the United States, Russia, and other nations.

After Reagan’s two terms as president, Vice President George H. W. Bush of Texas was his clear successor. Bush was one of the best-qualified presidential candidates ever: he had served with distinction as a pilot in the Pacific during World War II, as a successful oil businessman in Texas, as a US representative, as ambassador to the United Nations, as head of the Central Intelligence Agency, and finally as vice president. Christian conservatives were lukewarm toward the moderate Bush, however, and in the primaries they tended to support New York congressman Jack Kemp or the religious broadcaster Pat Robertson, who ran an energetic campaign as the first candidate produced directly by the Christian Right. Robertson’s campaign attracted millions of supporters, but his charismatic theology turned away some Christians who did not like Robertson’s emphases on divine “words of knowledge” and prayers for miraculous healings on his 700 Club TV show.

Figure 28.3. Sharon Christa McAuliffe received a preview of microgravity during a special flight aboard NASA’s KC-135 “zero gravity” aircraft. A special parabolic pattern flown by the aircraft provides short periods of weightlessness. McAuliffe represented the Teacher in Space Project aboard the STS 51-L/Challenger when it exploded during takeoff on January 28, 1986, and claimed the lives of the crew members.

Bush came out on top in the Republican primaries, partly through cultivating his ties to Christian leaders such as Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell. The Reverend Jesse Jackson once again made a strong showing in the Democratic primaries but lost eventually to the Democrats’ nominee, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis. Dukakis was the son of Greek immigrants and had a reputation as a capable administrator with left-wing social beliefs. Dukakis established and then squandered a large lead in the polls over Bush. Once again television ads played a major role in the campaign, as Bush ads lampooned a Democratic photo op that had Dukakis looking a bit ridiculous as he rode around in a tank, grinning underneath his oversized helmet.19 The ad suggested that there was a big difference between the reality of Dukakis’s opposition to Reagan’s defense buildup and the image of his feeble attempt to show himself as a martial leader. Racially charged ads by Republican groups made much of a prison furlough program in Massachusetts that had given a weekend pass to an African American man named William “Willie” Horton, who had been convicted of first-degree murder. On his weekend furlough, Horton had raped a woman and stabbed her fiancé. These kinds of ads convinced many voters that Dukakis was out of touch and hopelessly liberal.20

Bush’s popularity paled in comparison to Reagan’s among the Republican base. But Bush undoubtedly profited from Reagan’s legacy in a strong economy and foreign policy achievements, and he ran a hard-edged general election campaign. Bush trounced Dukakis in November 1988, winning 426 electoral votes to Dukakis’s 111. Bush would have to deal with a Democratic majority in the House and Senate, however. His desire to compromise with the Democrats on taxes—which he had promised never to raise—ensured that George H. W. Bush would become a one-term president. In the short term, however, Bush’s election seemed the natural extension of Reagan’s America.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brands, H. W. Reagan: The Life. New York: Doubleday, 2015.

Busch, Andrew E. Reagan’s Victory: The Presidential Election of 1980 and the Rise of the Right. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2005.

Collins, Robert. Transforming America: Politics and Culture during the Reagan Years. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Hankins, Barry, and Thomas S. Kidd. Baptists in America: A History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Halberstam, David. Playing for Keeps: Michael Jordan and the World He Made. New York: Random House, 1999.

Harvey, Paul, and Philip Goff, eds. The Columbia Documentary History of Religion in America Since 1945. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

Himmelfarb, Gertrude. One Nation, Two Cultures: A Searching Examination of American Society in the Aftermath of Our Cultural Revolution. Upd. ed. New York: Vintage, 2001.

Patterson, James T. Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Scalia, Antonin, and Amy Gutmann. A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Wilson, James Graham. The Triumph of Improvisation: Gorbachev’s Adaptability, Reagan’s Engagement, and the End of the Cold War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014.

15 “Steve Jobs Introduces iPhone in 2007,” YouTube video, 10:19, October 8, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MnrJzXM7a6o.

16 First Things, “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium,” May 1994, https://www.firstthings.com/article/1994/05/evangelicals-catholics-together-the-christian-mission-in-the-third-millennium.

17 “Retro Michael Jordan and Spike Lee Commercial,” YouTube video, 0:30, August 15, 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Abr_LU822rQ.

18 “Ronald Reagan TV Ad: ‘It’s Morning in America Again’,” YouTube video, 0:59, November 12, 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EU-IBF8nwSY.

19 “Commercial—Bush 1988 Election Ad,” YouTube video, 0:30, August 4, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9LyYD166ync.

20 “Willie Horton 1988 Attack Ad,” YouTube video, 0:32, November 3, 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Io9KMSSEZ0Y.