To the uninitiated, football can seem quite confusing. The advanced features of the game—plays, formations, and strategies—have been likened to chess in their complexity. Likewise, the fundamentals, such as scoring, downs, and penalties, are themselves far from readily apparent on initial viewings.

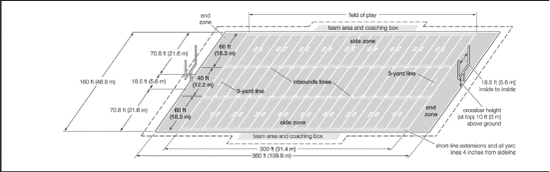

The field for American football is 120 yards (109.8 metres) long, including two 10-yard (9.1-metre) end zones, and 53.33 yards (48.8 metres) wide. A coin toss at the beginning of the game determines who will put the ball in play with a place kick from the 30-, 35-, or 40-yard line (at the inter-collegiate, professional, and scholastic levels, respectively) and which goal each team will defend.

Following the kickoff, the centre of the team in possession of the ball puts it in play by passing it between his legs to the quarterback, who hands it off to another back, passes it to a receiver, or runs it himself. Opponents try to stop any advance toward their goal line by tackling the runner or by batting down or intercepting passes. The offensive team earns a “first down” by advancing the ball 10 yards in four downs or fewer and can retain the ball with repeated first downs until it scores or until the defense gains possession of the ball by recovering a fumble or intercepting a pass. Failing to make a first down, the offensive side must surrender the ball, usually by punting (kicking) it on fourth down.

Football field according to NCAA specifications. Professional field varies slightly. Courtesy of the National Collegiate Athletic Association

The offense scores by advancing the ball across the opponent’s goal line (a six-point touchdown) or placekicking it over the crossbar and between the goal posts (a three-point field goal). After a touchdown, the ball is placed on the three-yard line (the two-yard line in the NFL), and the scoring team is allowed to attempt a conversion: a placekick through the goal posts for one point or a run or completed pass across the goal line for two points.

New York Jets player Marquice Cole (No. 34) reaches the ball across the goal line (known as breaking the plane) for a touchdown during a 2011 game against the Buffalo Bills. Al Bello/Getty Images

The defense can score by returning a fumbled football or an interception across the other team’s goal line for a touchdown, by tackling the ball carrier behind his own goal line (for a two-point safety), or by returning a failed conversion attempt across the opponent’s goal line (two points).

Another kickoff, by the scoring team, follows each score, and the same pattern is repeated until playing time for the half expires (30 minutes for intercollegiate and professional football, 24 minutes for scholastic). After an intermission of 15 or 20 minutes, a second half follows, with the team that lost the initial coin toss choosing to kick or receive. The team that has scored the most points by the end of the game is the winner, and tie games are settled by additional play, determined by varying rules at the different levels.

Detailed rules govern all aspects of the game: lining up and putting the ball in play, kicking and receiving, passing and defending against the pass, blocking and tackling. Penalties for infractions of the rules may be the loss of 5, 10, or 15 yards or half the distance to the goal line, the loss of down (for a foul committed by the offensive team), an automatic first down (for fouls against the defense), the awarding of the ball to the offended team at the spot of the foul, and disqualification. The most serious penalties are for various forms of excessive roughness.

The rules governing football in the NCAA, NFL, and NFHS have several minor variations. Time is stopped at the end of the first and third quarters, when the teams change goals. Each team is also allowed a number of optional timeouts, and time is automatically stopped for a variety of reasons during play and for commercials during televised contests. The result is that games last well beyond the actual playing time. In the NFL, games routinely exceed three hours.

The game is supervised by seven officials in the NFL, four to seven in the colleges, and as few as three in high school. All officiating crews have a referee with general oversight and control of the game, who is assisted by umpires, linesmen, field judges, back judges, line judges, and side judges.

A referee, in the white cap, discusses a play with a head linesman. Referees are in charge of officiating football games, with support from umpires, linesmen, and judges. Greg Fiume/Getty Images

The referee is the sole authority for the score, and his decisions on rules and other matters pertaining to the game are final. The referee declares the ball ready for play and keeps track of the time between plays when it is not assigned to another official. He administers all penalties.

The play on the field underwent continual innovation. Lacking the cachet of “college spirit,” the NFL since the 1930s had always placed greater importance on entertainment. The NFL formed its own rules committee in 1933 and immediately moved the goal posts to the goal line (to make field goals easier), liberalized the rules on passing, and spotted the ball 10 yards from the sidelines when it went out of bounds. Until that time, the ball was placed at the sideline, and a play had to be wasted in order to move it to closer to the middle of the field.

Subsequent changes, in 1935 and 1972, eventually placed the ball even with the goal posts. (The colleges made similar changes but settled on a “hash mark” one-third of the field’s width.) As the new rules opened up play, the Chicago Bears, under coaches George Halas and Ralph Jones, assisted by University of Chicago coach Clark Shaughnessy, reintroduced the old T formation, which eventually replaced the single wing as the dominant offensive formation. Quarterback Sammy Baugh and receiver Don Hutson elevated the passing game to new levels, while most college teams still played in a lower-scoring conservative style.

In the 1950s the Los Angeles Rams’ head coach Sid Gillman exploited the passing game as never before, but in the late 1940s and ’50s it was the Cleveland Browns’ head coach Paul Brown who revolutionized professional football with organizational principles that were eventually adopted throughout the football world. Brown made the watching of game films a part of the entire team’s preparation, placed assistant coaches in the press box, even experimented with implanting a radio transmitter in the quarterback’s helmet—a tactic quickly banned by the commissioner, not to be legalized for another four decades. Brown invented “pocket protection” for his quarterback, with the linemen not aggressively blocking, as on running plays, but dropping back into a pocket to shield the quarterback. Vince Lombardi extended this principle to running plays at Green Bay in the 1960s, having his linemen block areas rather than specific men and having the running back read which way his lineman blocked his man at the point of attack. The basic principle of brushing defensemen aside rather than overpowering them gave new flexibility to the running game.

College football gradually adjusted to the more pass-oriented professional style. After World War II, college and professional coaches borrowed from each other, always looking for ways to exploit an offensive or defensive advantage. The Southwest Conference had been known for its wide-open passing attacks in the 1930s, but college football remained fundamentally a power running game into the 1980s. College coaches’ most distinctive innovations in the 1970s and ’80s came in offenses that featured running quarterbacks—the triple-option schemes such as the wishbone and veer (with the quarterback handing the ball off to a fullback, pitching it to a tailback, or keeping it himself), offenses that were unattractive to the pros because they put quarterbacks at physical risk.

The original defenses had simply mirrored the positions of the offense. In the 1930s a 6-2-2-1 alignment became dominant (6 linemen, 2 linebackers, 2 corner-backs, and 1 safety). In the NFL, to stop the increased passing that came with the T formation in the 1940s, the Philadelphia Eagles’ Greasy Neale developed the 5-3-2-1 defense, which was in turn replaced in the mid-1950s by the 4-3 (actually 4-3-2-2) perfected by Tom Landry as an assistant coach with the New York Giants. In this alignment the defensive tackles kept blockers off the middle linebacker, who became the dominant defensive player. The 4-3 defense made stars of such middle line-backers as Sam Huff, Joe Schmidt, Ray Nitschke, Dick Butkus, and Willie Lanier.

The 4-3, in turn, yielded to the 3-4 in the mid-1970s, moving the emphasis to outside linebackers rather than the middle linebacker. The New York Giants’ Lawrence Taylor became the prototype outside linebacker in the 1980s, with tremendous speed to cover receivers and tremendous power to rush the quarterback. By the early 21st century both defensive alignments were in practice, with roughly equal use throughout the league.

Pass defenses had always been either man-to-man or zone (each back covering an area). In the 1970s, when zone defenses virtually eliminated long passes, strong running games—featuring backs such as Buffalo’s O.J. Simpson, Miami’s Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick, and Pittsburgh’s Franco Harris and Rocky Bleir—dominated the NFL. Landmark rule changes in 1977—banning defensive contact with wide receivers more than five yards downfield and allowing offensive linemen to block with their open hands—returned the advantage to the passing offenses. Small, quick offensive linemen gradually disappeared, replaced by 300-pound (140-kg) hulks who could hold off charging pass rushers with their extended arms and hands. There were eight 300-pounders in the NFL in 1986 and 179 in 1996. In 2010, the vast majority of linemen in the league weighed more than 300 pounds.

Led by the so-called “West Coast offense” developed by Bill Walsh for the San Francisco 49ers, the passing game flourished as never before (in 1980 there were more passing than running plays for the first time since 1969). Other coaches developed run-and-shoot offenses, no-huddle offenses, and one-back offenses (with four wide receivers and no tight ends). Defensive coaches responded with “combo” pass defenses (combinations of zone and man-to-man), and the cornerback who could dominate a wide receiver by himself emerged as a new star. Deion Sanders became the prototype for this position. Running attacks increasingly featured a single back, making stars of such players as Tony Dorsett, Eric Dickerson, Walter Payton, Barry Sanders, Emmitt Smith, and LaDainian Tomlinson.

More so at the professional than the college level, football became increasingly specialized. To the kicking specialists who emerged in the 1960s were later added extra blockers for goal-line offenses, extra defensive backs for expected passing plays, and a variety of offensive and defensive specialists for the multiple alignments that all teams employed into the 21st century.