Everything is not as simple as you assume.

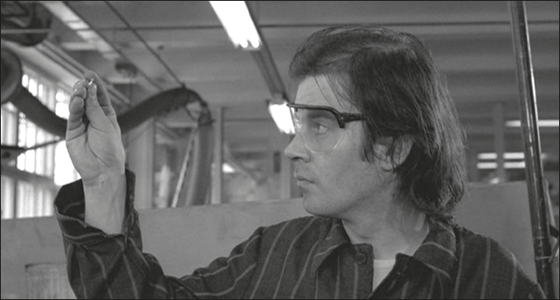

Antti Kalervo Rahikainen in Crime and Punishment1

Many critics have argued that Kaurismäki’s cinema opposes the culture that surrounds it and that nostalgia defines the films’ oppositional stance. One Finnish critic writes, ‘a sharp oppositional attitude to mainstream films has been characteristic of Kaurismäki from the very beginning. That comes from Robert Bresson and Luis Buñuel. Kaurismäki’s films are completely different from the mainstream…’ (Koski 2006). In this account, a nostalgic affirmation of these idiosyncratic filmmakers positions Kaurismäki outside contemporary cinematic culture. The Finnish film critic Peter von Bagh makes a similar point about The Match Factory Girl, arguing that the film’s minimalism is antagonistic to fashionable styles promoted in contemporary commercial media.

During a time in which the diarrheic language of television series is repeated all over the place and with ever decreasing critical awareness, and the premise of understanding as a condition governing language and communication is continually disparaged, [The Match Factory Girl’s] expressions and attitudes express a certain militancy. When someone speaks in The Match Factory Girl, it means something, and speech can create fateful consequences. (2002c: 143)

Kaurismäki’s cinema thus expresses a nostalgia for authentic communication, and in doing so attacks institutions of the present, television among others. Von Bagh maintains that ‘out-of-touch, increasingly technocratic and forgetful’ Goliaths use television ‘to keep the people quiet, and in place’ (ibid). In Kaurismäki’s diminutive nostalgia, television meets its David, implies von Bagh.

These readings of Kaurismäki’s cinema have proved influential; it is axiomatically taken to express nostalgia. Literary scholars Riikka Rossi and Katja Seutu sum up scholarly opinion in a fine collection of articles on Finnish literature titled Nostalgia (2007). Kaurismäki figures as the first example in their introduction – along with Proust. Rossi and Seutu write:

Although the protagonist of Kaurismäki’s Man Without a Past remembers nothing of his past, he is ensconced in a shared, secure-feeling past, which finds expression in the film through old music, cars, commercial items, and bygone urban and social images, in which a worker is paid in cash once a week. Desire for a unified community is a defining mark of nostalgia. (2007: 7)

This reading suggests that the film’s nostalgia gives material form to a wish for belonging, which transcends the wealth and power of the banks, the corporations, and state. Nostalgia here positions the community outside capitalism. The old music, cars, and commercial items associate this community with the past, and differentiate it from what does not appear in Kaurismäki’s films – the accoutrements of wealth and power: technology, glamour, eminence.

According to these observations, Kaurismäki’s nostalgia is a means of creating an oppositional position exterior to economic and political discourse and institutions. In this view, the power of Kaurismäki’s intervention lies in the position’s temporal exteriority. Aligned with the forgotten past, Kaurismäki can supposedly see differently than the empowered of the present day. He does not depend on social networks or the rules of the system, and so can speak freely. And he is liberated from conflicts of interest, which might silence him. Nostalgia hence serves to vouch for the moral soundness of Kaurismäki’s critique.

A key problem evident in such arguments about nostalgia, however, is that the temporally exterior position always remains unspecified. On the one hand, nostalgia invokes a longing for something not present, the ‘past as foreign country’: yet in being absent, the longed-for object is defined simply as an alterity, something other than what is present, something different than the current order. On the other hand, in fetishising the longed-for object of the past, nostalgia strips that object of a complex, potentially contradictory context. The nostalgic object can be longed for intensely because it figures against a whittled down background, before which it is simply an idealised goodness. If its context were specified, the nostalgic object could not sustain the idealising affective investment that makes it attractive in the first place. Aligned with such an object, the exterior position and the idealisation go hand in hand.

This chapter challenges such constructions of nostalgia and seeks to situate Kaurismäki’s cinema and his nostalgia in relationship to some influential arguments about nostalgia and the representation of time and space in film studies. It then seeks to show that Kaurismäki’s nostalgia is more complicated and embedded in mainstream cinema and culture than the definition of an exterior and oppositional position tends to acknowledge. Finally, it lays out an argument about the significance of Kaurismäki’s nostalgia by likening it to the ‘tactic’ as theorised by Michel de Certeau. The argument seeks to demostrate the interest of Kaurismäki’s cinema for film studies. At the same time, the argument contributes to Kaurismäki studies by bringing together arguments about a key theme in his cinema, and suggesting another perspective on them.

Nostalgia and Late Modernity

There are many examples in Kaurismäki’s films that suggest his nostalgia fits within late modernity and its systems, rather than seeking to define a position exterior to it. These examples suggest that we ought to reconsider the rationale motivating Kaurismäki’s nostalgia.

Kaurismäki’s films continually construct relationships between objects, attitudes, and institutional practices that we often think of as belonging to discrete historical moments of the twentieth century. In The Man Without a Past, for example, the main character M arrives in Helsinki by train in a ‘blue’ passenger car dating to the 1970s, the oldest style of car in use on Finland’s national railway (VR). VR has been replacing this equipment with Intercity and Pendolino trains. As film scholar Anu Koivunen astutely observes, M’s costume includes a style of leather boots and work clothes associated with an earlier generation of men (2006: 135); and arrival by train in Finland’s capital city also belongs to a historical narrative of the 1960s, not the 2000s. Yet M soon makes his home in a shipping-container village: the container was invented in 1956 and became the universal infrastructure for international shipping by the early 1980s (see Levinson 2006: 239). Containerisation has furnished the infrastructure for just-in-time manufacturing and the globalisation of consumer-oriented trade; the volume of goods shipped in containers quadrupled between 1980 and 2000 (ee Levinson 2006: 271). The container has transformed harbours around the world by providing a means of automation ten times less expensive than established bulk cargo loading, shipping, and unloading systems. The container can be read as a symbol of late modernity, that is the system of globalised capitalism involving broad, deep, and speedy flows of capital, deterritorialised relationships of production and distribution based on inexpensive labour costs, computerisation and automation, and a global consensus around economic policy tending to favour the interests of capital, that is, a neoliberal system. In featuring the container, The Man Without a Past includes images of Finnish modernisation and globalisation.

Another example of this symbolic combination is apparent in Drifting Clouds. Capital moves out of the Restaurant Dubrovnik, leading Ilona to lose her job and experience a humiliating chain of events, but the former owner of Dubrovnik agrees to finance a new restaurant when Ilona runs into her, reconstituting a utopian, nostalgic space and social configuration. When finance capital returns, the moral venture and crisp style of Restaurant Work (Ravintola Työ), becomes possible. The nostalgic restaurant is not outside modern capitalism or an alternative to it; it belongs to a strand within it, a combination of disjunctive elements.

A similar disjunction is evident in the way Kaurismäki’s cinema symbolically combines disparate elements of the history of cinema. Kaurismäki’s characters in Drifting Clouds, The Man Without a Past, and Lights in the Dusk recall Chaplin at work in Modern Times (1936), George Bailey (James Stewart) in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) and Erin Brokovich (Julia Roberts) in the eponymously-titled film by Steven Soderbergh (2000). Kaurismäki’s characters fall, they struggle, they come to understand themselves and the world around them more fully, and in some cases they even triumph. Kaurismäki signals the relevance of the Hollywood tradition, calling it to mind directly in Leningrad Cowboys Meet Moses, when the director appears as the little tramp working on the factory line. About this cameo, Kaurismäki remarks that he combined Buster Keaton and Charles Chaplin (in Nestingen 2007). The characters mentioned above and Kaurismäki’s characters all share a defiant view of the capitalist system. It is not only Kaurismäki who has combined the history of the cinema with his own view. We can also see how other filmmakers intersect with Kaurismäki in their filmmaking, among them Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, Jim Jarmusch, Dagar Kári, Mike Leigh, Quentin Tarantino, and Jia Zhangke. The interest of Kaurismäki’s nostalgia and his cinema lies in their messy embeddedness in Euro-American and World society and cinema, and the films’ representation of their history and transformation, rather than in their total opposition to other forms of cinema.

There is another way of avoiding the ‘outsider’ argument about nostalgia, which usefully points in a fruitful direction, and so lays in the background of the case I seek to make here. The films can be read as existentialist texts, not seeking an exterior position, but rather carving out a space of subjective authenticity. On one such account, this existentialist space is a variation of Freudian and Kristevan melancholia, in which the lost object of the past belongs to modernity, yet nevertheless exerts a pull on the subject, which keeps him shuttling between past and present in a bifurcated existence. By staging images of longing for a lost object, Kaurismäki’s cinema prompts spectators to long for the past, allowing them to occupy a space of movement between the late-modern, capitalist present and a space of longing internal to it (see Kyösola 2004b). Akin to this argument is the claim that representations of nostalgia in Kaurismäki’s cinema clear a space for Heideggerian Dasein. In this view, the nostalgic objects in Kaurismäki’s cinema stage the construction of a dwelling that resists the instrumental logic of modernity, creating a space for authentic existence (see Vermeulen 2007). The strengths of these analyses notwithstanding, they depend on the premise that the past is out there and amenable to representation, rather than constructed through representations and claims that construct past, present, and future in contingent relations to one another.

A more convincing way of approaching nostalgia as a part of late modernity is suggested by the essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ by Charles Baudelaire. Kaurismäki has written about Baudelaire, mentioned Baudelaire’s work in interviews, and he dedicated the film Calamari Union to the memory of Baudelaire, as well as naming the dog in The Bohemian Life after the poet. Baudelaire was hostile to nostalgia, for he viewed the contingent experiences of life in the modern city as the source of artistic originality. This was because the variety of experience could be synthesised by the modern artist, creating a vision of modern life. In ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, Baudelaire suggests that nostalgic representations can separate an artist from contact with the society surrounding him and thus diminish his originality:

If a painstaking, scrupulous but feebly imaginative painter has to paint a courtesan of today and takes his inspiration (that is the accepted word) from a courtesan by Titian or Raphael, it is only too likely that he will produce a work which is false, ambiguous and obscure … Woe to him who studies the antique for anything but pure art, logic, and general method! By steeping himself too thoroughly in it, he will lose all memory of the present; he will renounce the rights and privileges of circumstance – for almost all our originality comes from the seal which time imprints on our sensations. (2008: 14)

Gazing into the past distracts the artist from the people, spaces, institutions, and struggles surrounding him, causing isolation. Baudelaire’s emphasis on contingency and ‘the seal which time imprints’ maintains that it is an observant sensitivity towards life in modern society, its changing people, spaces, and images, that is the artist’s chief faculty. The artist must recognise the relevance of the past, but not be distracted from the present.

As a post-Romantic thinker, Baudelaire’s double vision negotiates the problems of idealisation and realism. The artist must not be seduced by the past as the putative idealisation of some entity of interest, but finds his originality in depicting the contingencies of modern life. We see the way Kaurismäki does this in his representation of shipping containers and capitalist dynamics in The Man Without a Past and Drifting Cloud, but also in his contemporary adaptations of Dostoevsky, Shakespeare, and Murger, as well as in his films’ citations of TV news and newspapers. It is also wise to avoid placing too great an emphasis on the existentialist elements in Kaurismäki’s cinema. As a subjective philosophy, existentialist thinking has trouble with the social awareness and observation we see in Baudelaire and in his impact on Kaurismäki. Kaurismäki is not a patient and scrupulous filmmaker who seeks to depict a contemporary worker by modelling him or her on the work of Teuvo Tulio or Robert Bresson, Valentin Vaala or Jean Renoir, Frank Capra or Yasujiro Ozu. We should not take Kaurismäki’s use of nostalgic representations to depict contemporary life by way of images of the past, or as a subjectively oriented existentialism, but instead ask about the films’ relationship to ‘the seal which time imprints on our sensations’. What is the aesthetic and cultural political relationship between Kaurismäki’s representation of contemporary Europe and the use of nostalgic images, sounds, and styles?

Nostalgia and History

Kaurismäki’s cinema has the potential to contribute to discussions of nostalgia in film studies and cultural studies. The films’ multiple temporal registers encompass American and European inter-war and post-war culture and cinema, especially the latter’s formal elements, its narrative styles, and many of its moral assertions, making it aesthetically and culturally suggestive material. Further, these references seem to concern history less than they insistently link up with present-day issues and debates. Given these features, it is no surprise that only one of Kaurismäki’s films is explicitly situated in the past: the TV film Dirty Hands, the Sartre adaptation. Kaurismäki has distanced himself from the film over his lack of production control (see von Bagh 2006: 73–5). Despite Kaurismäki’s reputation as a nostalgic filmmaker, his films are neither heritage films nor costume dramas, the genres most strongly associated with nostalgic cinema in Finnish, Nordic, and European film since the 1980s. The critical tone, minimalist style, and pastiche features of Kaurismäki’s cinema do not mesh with the middle-brow sensibility and production values commonly associated with nostalgic genres like the heritage film.

Kaurismäki’s films do include diverse temporal registers and objects belonging to different historical moments; this combination causes them to seem timeless in some ways. Yet at the same time the films are often specifically situated in their moment of production by way of topical references or diegetical dating. In Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatiana and Juha, for instance, the mise-en-scène of 1960s’ rural Finland figures centrally and certain aesthetic features conjure a sense of the past, for example the black-and-white image track and Juha’s production as a silent film. Yet the films also include narrative events and images that tie them to the present. In Tatiana, Manne spontaneously returns to Estonia with Tatiana, but without a visa, a journey not possible before Estonian independence from the USSR in 1991. In Juha, a microwave oven and a plastic package of meatballs roughly locates the diegesis historically. In Drifting Clouds and The Man Without a Past, a television broadcast and a newspaper masthead nail down specific dates, which heighten the clash with some of the older elements of mise-en-scène. This temporal mixing raises questions about how to approach Kaurismäki’s work in the context of some predominant theories about cinema and nostalgia.

Discussions of nostalgia often argue that it is a mode or representation that critiques history, but such arguments do not necessarily help unpack Kaurismäki’s cinema. In her influential and suggestive book Screening the Past, for instance, Pam Cook (2005) reads film texts’ nostalgic representations of the past in relationship to history. Cook makes the case that analysis of nostalgia is necessary to understand changes in notions of media culture and spectatorship. Shifts in the theorisation of media culture and spectatorship help make visible a variety of spectatorial relationships to history. Cook contrasts such arguments with apparatus theory and psychoanalytic film theory of the 1970s, which maintain that film texts overpower docile spectators, constructing a uniform relationship to history for them. Nostalgia, argues Cook, involves active viewers’ diverse uses of films to do memory work. Analysis of nostalgia allows us to discern the spectator’s historical self-construction in ways that link up with counter-narratives and critiques of canonical historiography. The richness of Cook’s argument notwithstanding, its concern with analysing nostalgia as a form of historiographical critique can distract us from the other kinds of nostalgia less concerned with history, such as Kaurismäki’s. Furthermore, the focus on history tends to emphasise the particular, or in Kaurismäki’s case, national history, which would only reinforce arguments about his exterior and distinct cultural position.

Another way to tackle nostalgia in Kaurismäki’s films is to approach it as melancholia, as Satu Kyösola and Anu Koivunen have done. Koivunen has suggested that Kaurismäki’s films give voice to a sense of the ‘loss of an ideal, be it the political project of the welfare state or the leftist revolutionary dreams’ (2006: 144). This melancholia finds seductive expression in nostalgic images and music, which Koivunen situates within a discussion of Fredric Jameson’s (1991) and Vera Dika’s (2003) related notions of the nostalgia film. Kaurismäki’s eclectic musical choices, ‘technicolor-inspired, carefully planned frames…’, as well as the immobile camera, and ‘lighting and setting produce elaborate compositions for the spectator’s pleasure’ (ibid.). The image track and soundtrack create a sensual experience, which generates a seductive, emotional register through which melancholic loss can be experienced. For Koivunen, however, the nostalgia and melancholy are only part of the picture. Kaurismäki’s films are an eclectic pastiche also combining sentimentality, irony, and political critique.

One of the points implied here is that nostalgic representations also use images of the past to create affective relationships to institutions and figures in the present. A compelling framework for this line of analysis is David Harvey’s argument about the consequences of time/space compression in his classic study The Condition of Postmodernity (1989). A defining feature of late or post-modernity is its systematic control of temporality – the capacity to make things happen rapidly by moving money, goods, commodities, people, and images around the world in short time spans. Time/space compression, impacts the temporality of social relations. Objects, relationships, and experiences become ephemeral, obsolescent, and disposable, because change can be brought about easily and inexpensively through resupply, replacement, realignment, or recontextualisation. As a consequence, the capacity to appear to resist change, to project durability, rises in value. In this context, the nostalgic image and the heritage industry gain cultural capital, in their capacity to create the appearance of durability. Harvey’s argument stands in contrast to Cook’s, for Harvey is concerned with the way images of the past are used instrumentally in political and economic discourses of the present, rather than to engage in historical debate. Kaurismäki is working within Harvey’s frame of reference.

Harvey’s argument about time/space compression bears directly on the production and marketing strategies of national cinemas in an era of globalised cinema, which is part of its relevancy to Kaurismäki. In Film History: An Introduction, David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson point out that small-nation cinemas have long used location shooting and narratives drawn from national history and literature to differentiate their films from mainstream American and European productions (2003: 78–9). Such an argument echoes Harvey by maintaining that nostalgia can generate distinction in the marketplace. At the same time, Bordwell and Thompson’s formalist account of nostalgia can overlook the dynamics created by asymmetries of history, business, aesthetics, and cultural politics, which distinguish Hollywood production and distribution from national and small national cinemas. The Hollywood majors and boutique producers have also registered the value of national nostalgia, which is visible in such films as The Lord of the Rings trilogy (Peter Jackson, 2001–2003), the Harry Potter films (various directors, 2001–2011), Chronicles of Narnia (various directors, 2005–2008) or nominally art-house hits like Babel (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2006) and Slumdog Millionaire (Danny Boyle, 2008). An earlier instance of the same phenomenon is Sydney Pollack’s adaptation of Isak Dinesen’s (Karen Blixen) memoir Out of Africa (1985), as Mette Hjort has argued (2005). Nostalgia is a key aspect of national cinema, as Bordwell and Thompson suggest, but also an overdetermined and contested element in a globalised film culture.

What we need then is a frame of reference for situating Kaurismäki’s nostalgia within the present, and in relation to the debates and critique his cinema involves, but also a framework that includes movement between multiple registers, as Koivunen argues.

The Temporality of Double Occupancy

Theories of nostalgia assign different roles to contemporary discursive actors. While some minimise their role in shaping our notions of the past, other maximise their role, making the past the construction of present-day actors. The latter approach is relevant to Thomas Elsaesser’s arguments about identity politics. In European Cinema: Face to Face With Hollywood (2005), as well as in an article on Kaurismäki’s Man Without a Past, ‘Hitting Bottom’ (2010; 2011), Elsaesser develops a notion he calls ‘double occupancy’. All European social identities involve displacement and multiplicity, because of Europe’s violent and migratory internal history. As the metaphor of two people holding or contesting one space indicates, double occupancy works in Elsaesser’s analysis primarily to discuss spatial relationships in film concerning identity discourse – the term is also a critique of ‘Fortress Europe’ and multiculturalist arguments (2010: 109–10). Elsaesser does not explore the temporal dimensions of the term, but developing an account of double occupancy’s temporal dimension helps illuminate Kaurismäki’s nostalgia and its relevance for film studies.

Kaurismäki’s Man Without a Past can be read as an allegory of double occupancy inasmuch as it depicts a community of citizens within the state, who are nominally bonded to the state by the social contract, but in practice living a citizenship under erasure. The protagonist M is governed by the laws and obligations of the Republic of Finland, yet is also a non-citizen, unable to receive any, which challenges recognition let alone benefit from his status as citizen. In this character, the political notion of citizenship is in conflict with the neoliberal economic discourse that has recast the citizen as consumer. In Elsaesser’s account (2010), Kaurismäki’s critique of citizenship is an instance of double occupancy, for it shows the emptiness of political and economic categories of citizenship at the same time as it elaborates an ethics of tolerance and humility that seeks to displace the political and economic discourses of citizenship. This argument places great emphasis on double movement, contestation, and ambivalence. Different concepts of citizenship are involved in a contest that will alter all notions involved, and will not produce a singular winner.

In speaking of double occupancy, Elsaesser discusses similar dynamics to the temporal and aesthetic ones theorised by Baudelaire, when the latter argues that no pure aesthetic models are available in the work of the masters of the past, but that the artist must shuttle between past and present, general and particular. Past and present are involved in a relationship of double occupancy within the artist’s creative practice. The allegory of double occupancy Elsaesser identifies in The Man Without a Past is also relevant to nostalgia in Kaurismäki’s films, for it gives us a way of recognising how nostalgia also works as a form of temporal double occupancy that disrupts – or to use Elsaesser’s term, interferes with – notions of homogeneity and singularity, and prompts us beyond the usual identity categories.

The categories and identities involved in double occupancies always have a history; a symbolically significant identity or place often carries importance precisely because of its temporal status, its salience justified by temporal claims. A place has always been the home of this or that ethnic group, creed, or language. Yet such histories are always fraught, subject to multiple claims. Institutions and cities take shape through histories of gender, class, ethnicity, construction, and inclusion, but also destruction and exclusion. The dynamics are evident in the built environment. To take a classic example, the financial operations of capital cities concentrate capital flows into specific areas, which require infrastructure and tertiary services facilitating capital flows. The investment bankers not only need their Bloomberg monitors, but the infrastructure, real estate, and amenities that define their social status. These latter often push older forms of culture and commerce out of the way, which alters the cultural and symbolic ecology. The present and the past make competing claims on the same urban space. In a different vein, the ‘smoking ruins’ of postiwar Finnish modernisation – the brutalist cement apartment blocks of eastern Helsinki, the Pasila district, or the town of Lahti, for example – seek to generate equality into the future by erasing the uneven development of the past, and its wooden construction. This is a version of double occupancy that bears on the definition of the nation as ‘modern’: old and new both make their claims on the same space. Nostalgia in Kaurismäki’s cinema stages such conflicting claims of past and present, and in so doing engages in double occupancy. Double occupancy, then, must also be understood to involve multiple and contested temporal claims on subject positions, spaces, and institutional status. Kaurismäki’s nostalgic images arguably interfere with or disrupt the temporality of the national and European narrative promulgated by officials, in which the Finnish welfare state, and the European Union, grow and enrich themselves, having moved from the welfare-state phase to successful competition in the global economy, according to the officials.

The temporal dimension of double occupancy is important, for it shows the perishability of national and supranational narratives of progress. In this case, the Finnish state and the EU continually present themselves as durable, whether because of their history or because of the institutional consensus on which they rest. Yet as they continually repackage their self-presentation, to respond to the issues of the news cycle, they also highlight their vulnerability. This temporal dialectic has been analysed by Andreas Huyssen. Huyssen writes that ‘as the more the present of advanced consumer capitalism prevails over past and future, sucking both into an expanding synchronous space, the weaker is its grip on itself, the less stability it provides for contemporary subjects … There is both too much and too little present at the same time…’ (2000: 33). If the leading edge continually razes the past to make room for new buildings, networks, lifestyles, images, and consumption, this tendency is also a kind of self-cannibalisation. The present attacks itself, because it gets old too quickly. Even a present-day expression of nostalgia for some past object or moment does not preserve the past in the present, but is an ephemeral representation in a present that quickly erases itself. Because ‘there is no pure space outside of commodity culture, however much we may desire such a space … [m]uch depends, therefore, on the specific strategies of representation and commodification and on the context in which they are staged’ (2000: 29). Nostalgia is also haunted by its contingency in relation to the past and the future. Discourses of nostalgia must struggle with the issues of durability, historical justification, and obsolescence typical of late modernity, and accordingly develop strategies of representation.

A good example of the temporal double occupancy in question is evident in fashion photography, and more broadly in manipulations of body image by way of powerful beauty products, plastic surgery, and other medical interventions. Kaurismäki rejects the standards of beauty promoted by the fashion industry and Hollywood. ‘People ask me, “Why do you use such ugly actors?” For me, they’re beautiful. I don’t know what people mean by beautiful actors. Bruce Willis, maybe?’ (in Romney 1997: 13). The notion here is one of authenticity in contrast to manipulation. The images of celebrities and models that appear on the covers and in the contents of fashion magazines are routinely manipulated with image-processing software to correlate with idealised and presumably impossible notions of beauty. These images entice consumers to aspire to a future appearance, but undermine one’s foothold in the present, which is defined by its lack and its possibility for transformation in the future. ‘Heartless retouching … has taken a much too big part in how women are being visually defined today’, says a fashion magazine art director commenting on a controversy created by several French magazines that rejected image manipulation (Wilson 2009). In other words, the present is too powerful, for the fashion magazines establish an impossible standard; but at the same time the present is too weak, continually inadequate in relation to the standards it projects into the future or nostalgically conjures from the past. Yet if this contested present results in nostalgia for authenticity, we can immediately see that nostalgia, too, is contested by multiple claims. Producing nostalgic and authentic-looking images leads to alternative forms of image manipulation and presentation, for example lighting and colour design, or layout and font, which of course also result in defining the present in terms of lack, inviting other, more fashionable representations. Nostalgia can be seen as simply another available tactic for product differentiation, and so subject to the same contradictory claims on its status.

Kaurismäki’s nostalgia provides a means of studying nostalgia as an intersection between a number of cinematic and cultural discourses. It stages a contestation of the present via the past in ways that arguably bolster several cultural-political outlooks. Arguments about nostalgia in Kaurismäki’s work have nevertheless tended to circumscribe his cinema in narrowly national terms, overlooking the multiple claims possible. Yet when we look at the struggles over this cinema, we will find that such limiting arguments continually run up against a disruptive aspect within the nostalgic articulation, a staging of double occupancy, if you will. By outlining three varieties of nostalgic stories told about Kaurismäki’s cinema – archivist, anachronistic, and ethical nostalgia – an alternative view of nostalgia in Kaurismäki’s cinema comes into view, what I call everyday nostalgia. Everyday nostalgia brings us back to the issue of double occupancy, which can be elaborated further to show the way Kaurismäki’s cinema calls for a category of national cinema, but also disrupts and undermines such a category.

The Stupid People

The name of this model comes from the book Tyhmän kansan teoria (Theory of the Stupid People), a thought-provoking 1994 study by the folklorist Seppo Knuuttila. In his critique of folklore, anthropological, and cultural theory, Knuuttila identifies a version of colonialist theorising that works by way of the critic identifying the text on which he’s commenting with a stigmatised yet also potentially positively valued representation of the past, at the same time as the critic designates himself as representative of that past. Knuuttila’s argument is reminiscent of Gayatri Spivak’s arguments about the subaltern. Elites can see the people as ignorant, static, parochial, and pre-modern. A romanticised view of the same people finds in them originality, custom, devotion, and authenticity. In Finnish national discourse, the Finnish-speaking, land-owning peasantry functioned as the central symbol and constituency for the construction of a national culture during the nineteenth century. Folklore studies were crucial in attributing this identity, for scholars of folklore could produce a folk and nation capable and worthy of bringing together the Swedish-speaking elites and the Finnish-speaking peasantry in a unified nation. Finnish-speaking academics and writers often sought to encourage identification with the folk by way of the ‘stupid people’ argument. The argument rests on the notion that the ‘ordinary people’, sub-alterns, left behind by modernity and stuck in the past, need an intellectual advocate to make their case to the elites. The people are too simple, or stupid, to represent themselves. Elites, for their part, need to learn from the ordinary people, for ordinary people’s connection with the past is not a liability, but in fact a connection to authenticity and tradition, which can be seen as a moral source for the nation. Because elites cannot fully appreciate the ordinary people, the latter’s champions must make elites see the masses’ inherent genius. This relationship is always tense in its normative aspirations.

The sociologist Pertti Alasuutari (1996) has analysed a similar phenomenon in discourses of Finnish national identity, although he places more stress on the power differentials involved. He argues that ‘suomalaisuus puhe’, or Finnishness talk, works in a twofold manner. Commentators define national characteristics in ways that essentialise the object of their discourse while elevating themselves to a position external and implicitly superior to the ordinary people. The power differential makes assuming the role of commentator highly valuable, for the commentator can speak in the name of the people to the empowered, while positioning himself outside both formations.

Stupid people arguments about Kaurismäki’s nostalgia became prominent during the 1990s, and in particular with the road film Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatiana. Such arguments can of course be made about his early films. One critic called a 1983 article ‘Crime and Punishment in Helsinki: The Past in the Present’, a title that indicates the extent to which what critics now call nostalgia was evident in Kaurismäki’s first films (Montonen 1983).2 Yet the archive of Finnish and international criticism on Kaurismäki from the 1980s treats him not as a nostalgic but examines his aesthetic and philosophical agenda. Analyses focused on the films’ intertextuality, the links to the French New Wave, Kaurismäki’s prolific production pace, his films’ connections to Finnish rock music, existentialist themes, the paternalism of the Finnish state, and the poor quality of Finnish cinema, among others. Stupid people accounts of Kaurismäki’s nostalgia correlate with the shift to the Third Republic, discussed in chapter two. This shift also correlates with Kaurismäki’s rise to international prominence on the film festival circuit. Suggesting that Kaurismäki spoke for the people, but that Finnish elites did not recognise this genius who had been recognised abroad, lent emotional force to stupid-people arguments.

The stupid people argument is strikingly present in a 1991 conversation between Kaurismäki and Peter von Bagh:

PvB: Your films’ characters, as well as the milieus, have a sort of ineluctable innocence, which is in no way a phenomenon of today’s Kingdom of Esko Aho.3 We don’t find the perverse types we find everywhere else nowadays.

AK: The most modern figures are from somewhere in the 1960s or 1970s. It’s figures from the 1970s who are the workers in my films, and that’s probably about right for today, too. Workers don’t change in the workplace, although that doesn’t apply to what they do in their leisure time. Workers still wear their coveralls, and happily they still do not use plastic in the production of industrial equipment, which means we can shoot on the factory floor. It seems pretty much impossible for me to put a computer terminal in the frame. I don’t know where I picked up my hate for contemporary design, including lived environments, buildings, cars, and clothing. Maybe it’s not hate for modernity so much as love for the past – which I’ve only seen in the movies anyhow. (1991: 10)

Von Bagh’s sarcastic political contextualisation of Kaurismäki’s cinema reveals several registers that recurrently turn up in the stupid-people arguments. Von Bagh’s comment asserts that Kaurismäki’s films transcend the political circumstances of the day – vouching for their aesthetic status. Second, von Bagh suggests that the source of the films’ transcendence is their guileless characters, who stand in sharp contrast to the politician and the perversity he represents. Finally, von Bagh stakes out an outsider position for Kaurismäki and himself by implying that appreciation of the films’ characters’ innocence is unusual in society at large. In the remark then we have an aesthetic argument, a political critique, and a discursive positioning as dissident. In these we find a link to a ‘foundational fiction’ of Finnish national culture, that elite and people are separated but should be united (see Koivunen 2006).4 By positioning the humble characters of Kaurismäki’s films against the ascendant politician and the narrative of erosion in which he figures, von Bagh asserts that Kaurismäki’s films are the corrective to the perversity. Von Bagh and Kaurismäki invoke a set of associated oppositions that structure their position and related nostalgia: metal versus plastic, artisanal craft versus automated production, labour versus capital, materiality versus abstraction, locality versus globalism, perversity versus moderation, past versus present.

Such a chain of associations also figures prominently in the work of critic Lauri Timonen, an associate of von Bagh. Timonen wrote the first book in Finnish on Kaurismäki’s cinema, and has written numerous articles on the director including several in The Finnish National Filmography, arguably defining the canonical view. He has also made a short film, produced by Kaurismäki’s Sputnik Ltd. Timonen puts nostalgia at the heart of Kaurismäki’s cinema, making him both outsider and spokesperson for the ordinary people; ‘The distinguishing mark of Aki Kaurismäki’s cinema is its “double-vision”, which seamlessly juxtaposes present and past, in which the latter stands as the measure of the former. Once things were better in the world and among people, and since things have declined, maybe forever’ (2005: 57). Timonen argues for a different double-vision than the kind analysed by Baudelaire or Elsaesser. Timonen maintains that what is at stake in Kaurismäki’s cinema is not only love for the past, but a pure and unsullied past, which stands as an opposite to the present. Such a view associates the past with an exterior discursive position, because it implies that that position in the past is characterised by harmony and wholeness. It is also an example of the theory of the stupid people, or ‘Finnishness talk’.

The Archivist

An interesting argument about the aesthetics of Kaurismäki’s nostalgia, which also involves some of the weaknesses of the stupid people theory, is evident in what Kaurismäki scholar Satu Kyösola has called ‘archivist nostalgia’. Cinematic authorship here is understood as a tool for expressing a personal outlook, which values conserving and preserving a disappearing past, which would otherwise be destroyed. ‘Archiving what will soon disappear is an attempt to refashion irreversible time, to master the ephemeral, to preserve the vanishing, to keep in memory what one is destined to forget, even if the task is condemned to failure’ (Kyösola 2004b: 47). Kaurismäki has spoken about his films in this way, as Kyösola shows. This argument links to the stupid people argument, for it supposes that the archivist must act on behalf of the people to identify and collect what would otherwise be lost, because the people would not preserve it.

The argument about archivist nostalgia understands nostalgia as a variety of realism. Cinematically, the argument is a version of André Bazin’s theory of film, and culturally it is a variety of what Svetlana Boym calls ‘restorative nostalgia’ (2001). In the cinematic dimension, the argument maintains that Kaurismäki fills the frame with outdated objects because he wishes to freeze the decline incurred by capitalist modernity’s creative destruction. This claim de-emphasises the aesthetics of representation and focuses on the way Kaurismäki ostensibly records objects and spaces on film, employing depth of field and long takes that allow spectators to register and contemplate objects and spaces, and the people using and inhabiting them. In its cultural dimension, the argument implies that the films ‘musealise’ as a way of compensating for loss; that is, the filmmaker collects and records as a means of creating an alternative cultural space in which values of the past are preserved and can continue to speak.

The plausibility of this argument is made plain in the films. In the opening sequence of Ariel, for example, we see the keskiolutbaari, the jukebox, Taisto Kasurinen’s cardboard valise, the transistor radio, and an old Cadillac. Indeed one of the recurrent settings in Kaurismäki’s films is the keskiolutbaari or ruokabaari, an institution associated primarily with rural Finland of the 1970s, as discussed in chapter two, but now largely gone. One book on the institution construes such beer bars as ‘the people’s living room’ (see Numminen 1986). Ilona works in such a bar in Drifting Clouds, Rahikainen eats lunch in one early in Crime and Punishment, Iiris has a beer in one in The Match Factory Girl, and M and Nieminen visit one in The Man Without a Past. As a ‘low’ cultural site, stigmatised by the alcohol regulatory discourse, such bars connote authenticity, suggests Anu Koivunen (2006). Not only are these places, things, and curiosities old, they carry an indexical realism: someone had to find them, register them, collect them, before they disappeared.

Kyösola puts emphasis on the combination of temporal, national, and cinematic discourses in Kaurismäki’s films. In a reading of Juha, for example, Kyösola argues that the silent film’s intertext introducing Juha and Marja as figures defined by their childlike happiness’ uses the Finnish countryside and material culture of the 1950s and 1960s to indicate that the past is a moral source of innocence and happiness (2007: 178). Home within the national past can be preserved by the cinema, even if the cinema can only substitute for this lost object. Kyösola emphasises the collecting practice necessary to Kaurismäki’s films’ mise-en-scène, linking the director’s project to the Snellmanian Fennomani collectors of the late nineteenth century, who sought to collect folklore and material culture as a means of documenting the richness of, and preserving, the national past (2004b: 47–8). This realism makes Kaurismäki’s cinema a sort of indexical representative of his nostalgic mentality: his films are the smoke which bears witness to the fire of the past. Kyösola points out that the dedication of a film like Ariel, to ‘the memory of Finnish reality’, or Tatiana, ‘a personal farewell to old Finland’, indicate the significance of the archivist project for Kaurismäki. Ariel, Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatiana, and Juha preserve a national innocence, which though lost continues to provide an aspirational ideal (see Kyösola 2007).

The story of archivist nostalgia also involves a problematic notion about the stability of the past, that overlooks the ambivalence we highlighted in discussing temporality and double occupancy. When we take for granted that the past can be represented through indexical realism, we assume that the past is given, unchanging, and uncontroversial. The past is reduced to a fetishised object: a jukebox, a Cadillac, a valise, which communicates a simple meaning. An old-fashioned beer mug in the keskiolutbaari stands for authentic community. But, as we saw in our discussion of the history of alcohol discourse in Finnish history, that beer mug and the context in which it is drunk from has been fraught with conflict. Such debates continually change in meaning as they are used in diverse contexts towards different ends. What, then, does a nostalgia premised on indexical realism show us? We cannot take present or past for granted, Elsaesser and Huyssen argue, for the past is a subject to double occupancy.

Anachronistic nostalgia sees Kaurismäki’s films’ nostalgia as constructed through mise-en-scène and formal principles that are purposely disjunctive in their representation of past and present. The disjointed temporal representation in the films works to question the historical narratives of triumph and progress told about Finland’s modernisation, Europeanisation, and globalisation between the 1940s and the 2000s. The anachronistic nostalgia story implies a similar claim to the one Pam Cook makes about nostalgia, maintaining that the aesthetics of Kaurismäki’s cinema critique historiographical constructions of post-war Finland. This understanding of Kaurismäki’s cinema might also be compared to Svetlana Boym’s (2001) concept of reflective nostalgia, which constructs self-aware gaps in its representation of the past, allowing for the pleasure of nostalgia but also providing the intellectual distance that putatively fosters critical examination of the relations between past and present. The argument has been advanced by the sociologist Ilpo Helén, and echoed to some degree by film scholar Anu Koivunen (2006). A version of it has also been elaborated by Henry Bacon (2003) in an analysis of the anachronistic representation of urban space in Kaurismäki’s films, which he speaks of as a poetics of displacement. Pietari Kääpä (2008) has also contributed to this view, arguing that the disjunctive spaces of Kaurismäki’s cinema cannot be reconciled in a single national space.

The evidence for the anachronistic nostalgia story is particularly clear in images that appear to date Kaurismäki’s films in a historically specific manner. The Match Factory Girl includes television images of the demonstrations at Tiananmen Square in June 1989, The Man Without a Past shows a dated newspaper. In Drifting Clouds, we hear a television news broadcast from Finland’s public TV1, which relates news of Typhoon Angela’s landfall in the Philippines and the execution of Ogoni author Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni activists by the Nigerian government. Included as diegetic sound, the news broadcast is an ostensibly authentic one which dates the film’s narrative precisely to TV1’s reporting of these events in November 1995. Yet this apparently specific dating also includes a disruptive anachronism. Presented as a single report on historical events that have occurred within the film’s diegesis, Typhoon Angela and Saro-Wiwa do not actually belong together, or in the same news broadcast. Typhoon Angela struck the Philippines on 2 November 1995, killing 882 people and resulting in damages worth 9.33 billion Philippine pesos before the storm dissipated in the Gulf of Tonkin on 7 November 1995. Saro-Wiwa was executed on 10 November 1995. In other words, the documentary referent has been constructed through editing, yet is presented to imply historical specificity. On the anachronistic nostalgia account, this construction shows us Kaurismäki’s method in microcosm. By constructing the film through disparate temporal units of meaning, which invite a realist reading and assumption of continuity, the films create apparent unities from parts that under analysis reveal clashes. The contradictions among the images and units of meaning disrupt the reality they appear to represent, thereby raising questions about the relationship between representations and their referents, signifiers and signifieds.

A useful elaboration of the argument is offered by Ilpo Helén in a reading of The Match Factory Girl. He argues that the representation of time in Kaurismäki’s films questions the possibility of community, which the films construe in quasi-Marxist terms as the construction of the ruling class:

The milieu inhabited by Iiris Rukka, her mother, and her stepfather appears as a working-class home from the late 1960s and early 1970s (albeit with a television broadcasting news broadcasts from the 1980s). Aarne, for his part, is a 1980s’ yuppie. These contradictory strata are tied together in the figure of Iiris. Yet the contradictions that constitute the ahistoricism contrast sharply: the 1960s and 1980s are not tied together by historical change and development, but by exploitation and alienation. (1991: 18)

For Helén, the films put emphasis on anachronistic contrasts that show how national elites have constructed the nation as a unified, historical agent. The contrasts make clear that the historical discourse of unity and collective agency is in fact built upon and sustains exploitation that secures the interests of the elite. The many anachronistic juxtapositions, suggests Helén, disrupt national historical narratives, raising questions about the narrative of national advancement, progress, and self-understanding. Helén’s argument can be compared to Harvey and Huyssen, for Helén argues that Kaurismäki stages a ‘failure’ of heritage-industry principles to show the way the state uses heritage-industry stories to create a narrative of national progress.

Yet if the purpose of Kaursimäki’s anachronistic nostalgia is to stage an interpretive dilemma, the dilemma created can easily lead to other construals of the nostalgia when we put greater emphasis on the aesthetics, and less on cultural politics. One aesthetic route is to note that the anachronisms contribute to a recurrent representation of isolation, which suggests an entirely different kind of nostalgia than we have discussed so far. A second route sees the anachronisms as constituting an aesthetic entirety that in sum gives proof of the artistic genius of Kaurismäki as a modernist filmmaker.

Nostalgia is a collective emotion, one which conjures shared experiences of the past. The Latin roots nostos and algia, points out Svetlana Boym, literally mean a longing for a home most often connoting a homeland, people, or ethnos (2001: 3). Desire for a unified community is a seminal feature of nostalgia in Kaurismäki’s cinema, suggest Rossi and Seutu (2007). Yet does the nostalgia express a desire for community? The films formally chop up and isolate their characters, often depicting social groups and institutions as the enemies of the isolated characters in the films. Henri Boulanger does not long to return to France (they did not like him there), the Leningrad Cowboys do not long to return to the plains of Ostrobothnia, and many of the films conclude with escape rather than reunion. This anti-communal dimension is evident formally in the films. Over and over, editing is used to depict characters as cut apart and cut off. In The Match Factory Girl, the composition of the shot depicting Iiris’s stepfather’s visit to the hospital cuts off his head, creating an image of separation and alienation – in addition to a cinematic pun.6 After M is beaten in The Man Without a Past, we see discrete images of his hand, his back, his feet sticking out in the bathroom, each of which emphasise his dismembered, dehumanised abjection. Nikander’s lonely execution of his daily routine in Shadows in Paradise – driving the garbage truck, shopping at the grocery store, preparing dinner for himself – use composition and lighting inspired by film noir to underscore the character’s isolation. In examining these themes and formal elements, it begins to seem that the object of nostalgia is not community, togetherness, or fullness, but loneliness, alienation, and exile. The disjunctions of anachronistic nostalgia can thus be seen to stage isolation formally, as a means of giving emphasis to the experience of men whose principles cast them ‘out of time’, hiving off their existence, the Raskolnikovs and Rahikainens.

In this version of anachronistic nostalgia, it becomes comprehensible in aesthetic terms as the articulation of a longing for the cinematic representation of isolation prominent in some American and European inter-war and post-war cinema, and in particular the auteur cinema, in which Kaurismäki finds his inspiration.7 We see this detachment in French poetic realism, for example. Isolation defines the characters of Jean (Jean Gabin) in Port of Shadows, as well as Gabin’s roles as the title character in Pepe le Moko and as Jacques Lantier in La bête humaine. Similar disconnection figures in the protagonists of Hollywood film noir too, for example Roy Earle (Humphrey Bogart) in the early noir High Sierra (1941), or Philip Marlowe in the adaptations of Raymond Chandler’s hardboiled fiction. Godard’s characters are also often deeply isolated, from Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) to Lemmy Caution (Eddy Constantine). Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel films are a study in isolation. We find similar representations through the canon of the European art film. In this view, then, the formal gaps and disjunctions that comprise anachronistic nostalgia can fetishise isolation as it figures in the history of cinema.

When we put the emphasis on the aesthetics of anachronistic nostalgia, yet a final and different account emerges. Film critic Markku Koski argues that the anachronisms are the mark of modernist, aesthetic originality. He draws on Georg Simmel to make this case, recalling how Simmel argues that art stands in contrast to design and craft, inasmuch as design is defined by consistency of stylisation and hence can be understood to represent the style of its times. The artist invents his own inimitable idiom, which attracts attention because of its comparatively exceptional and transgressive qualities. Koski writes:

The office of a large company, a government agency, or a furniture company’s display at a design convention must be carefully stylised; comparable unity of stylisation in a home would betray bad taste or social striving. A stylised home is not a home; it is a representational object … The images in Kaurismäki’s films, full of anachronisms and stylistic blunders, are realism that has been coloured in a unique way. Our homes, surroundings, and clothes are full of similar anachronism. (2006)

The problem with this account is that cinema is here reduced to a question of personal style by way of a metaphor that equates the film artefact with the home or one’s wardrobe. By finding an equivalence between decorating one’s home or choosing one’s clothes and making and putting into circulation hundreds of prints of a film, Koski reduces a broad cultural dialogue into an instance of personal expression. In so doing, the anachronistic nostalgia in question loses its social or political interest.

By creating gaps and disjunctions, Kaurismäki’s films can be seen to open holes that invite filling, that is to say dialogue. That process results in multiple claims and instances of double occupancy. The many layers of Kaurismäki’s films at least stage a problem of dialogue, which cannot be reduced to the singular statement or style attributed to the director. In making visible the rich layering of these films, the anachronistic nostalgia view pushes us beyond the kind of formalist reading advanced by Koski, and towards the open-ended questions raised by Helén, Koivunen, Bacon, and Kääpä. The issue is whether the questions made possible through anachronistic nostalgia are present for their own sake, or whether they figure in some broader project. In turning to a further account of nostalgia, the ethical nostalgia view, we find one description of what such a project may be.

Ethical Nostalgia

Ethical nostalgia is well illustrated by an anecdote Kaurismäki tells about the Arriflex camera he purchased from Ingmar Bergman:

I still make films on Bergman’s old camera. When Bergman quit directing films with Fanny and Alexander I bought his old camera. I still make films with it, although I have a more modern camera. The one I bought from Bergman is just more beautiful. That is, I do not film with it because it is Bergman’s old camera, but because it is simply a beautiful camera. (In Puukko 2000: 474)

On one level, there is an ethos of craft in this discussion: the beautiful tool facilitates the craft by inspiring the artist. Mastery of the tool involves a quasi-feudal continuity of craftsmanship, as the apprentice dutifully learns his trade from the master.

In a second dimension, Kaurismäki’s comments on Bergman’s camera can also be understood as a nostalgia that contests contemporary filmmaking practice. By using Bergman’s camera, Kaurismäki creates a material link between his films and a specific tradition of visual expression, which Kaurismäki suggests differs from what he alleges is a contemporary decline of visual expression:

The trend has gotten to the point where during the last two decades there has been a conscious effort to cultivate generations of viewers who will only watch certain kinds of films. The film clubs were destroyed so that no one could inadvertently demand anything but what is being offered. Viewers are no longer aware of cinema’s magnificent history. (Ibid.)

Bergman’s camera serves as an object of dissent, a way of using nostalgia to claim a history that challenges viewers’ assumptions about the cinema, and proposes alternative modes of filmmaking. The tool of the filmmaker introduces an alternative, by which visual culture can be revitalised to undermine its predominant form of production.

Finally, the ‘beauty’ of Bergman’s camera also involves an ethos of intrinsic value. Bergman’s camera is not only a means of establishing continuity and unity with a craft tradition or history of visual expression; in providing no justification for its use other than its beauty, the camera expresses a self-reflexive opting out of discursive justification. It is simply beautiful. As a consequence, it is not only an affirmation of beauty, but dialectically a rejection of technological choices motivated by marketing agendas and audience tastes. Such choices are construed by Kaurismäki as cynical, soulless, and destructive of film culture. Films like Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (George Lucas, 1999) illustrate the target of Kaurismäki’s critique – a conceptually conservative text whose value arguably rests on its status as a brand and potential return as an investment instrument.

An argument about ethical nostalgia which takes as its premise some notion of opting out of commerce must confront Huyssen’s claim that there is no outside to the commodity culture. As we saw in the Introduction, Kaurismäki’s visibility in the domestic and transnational media has been built on the critical and commercial successes of his films primarily at the A-List European film festivals of Berlin, Cannes, and Venice. The festivals are crucial to the financial success of the films in the many markets in which they are distributed. The ethical nostalgia rejects the economic success that makes possible the visibility. But an art film that grosses €40million, as did The Man Without a Past, generates broad media attention (see Näveri 2002a, 2003). While Kaurismäki and his cinema advocate for simple values of the past, the platform for such advocacy, Kaurismäki’s cultural power, derives largely from his success and visibility.

Everyday Nostalgia

Halfway through Ariel a Finnish judge unjustly puts Taisto Kasurinen in prison for appearing to commit assault with a deadly weapon. The sentence ends the laid-off miner’s search for a job in Helsinki, and also disrupts his new relationship with Irmeli, who is working four jobs to repay multiple loans. One of the jobs is as a slaughterhouse worker, a metonymic occupation for a dehumanising capitalism in Kaurismäki’s cinema. Made with Bergman’s camera and adhering to Kaurismäki’s idiosyncratic aesthetic, Ariel might also be understood in terms of ethical nostalgia. There is another dimension of nostalgia in this film and in Kaurismäki’s filmmaking practice, however, which has gone unremarked but which enriches the account of nostalgia in Kaurismäki’s cinema. We can call it ‘everyday nostalgia’. The adjective everyday connotes an attitude, affective stance and set of practices motivating the nostalgic elements in the films and the filmmaking practice. Focusing our analysis on the attitude, its cinematic representation, and associated filmmaking practice helps capture the double occupancy and immanence in Kaurismäki’s nostalgia. Everyday nostalgia involves an attitude that leads to a many layered negotiation between past and present.

Everyday nostalgia is evident in Taisto’s entry into prison in Ariel. When Taisto arrives at the prison, a processing officer’s questions elicit the matriculating prisoner’s name and former occupation, while revealing he has nothing else: no religion, no place of residence, no home or address, no living family, no spouse, no children, and worldly possessions ironically comprised of a watch, a cigarette lighter, and a Finnish social insurance card in a wallet empty of cash. Is Taisto as a representative of the past, a melodramatic victim of the present? Should we read this scene as an allegory of an all-powerful capitalist system crushing a diminutive citizen? No, for Taisto is a scrapper and a survivor, rather than a lumbering monument of the past. There is a level of entanglement and negotiation between present and past in Ariel, also evident in the other films. Moreover, this negotiation points towards an analysis of Kaurismäki’s relationship to cinema. As a filmmaker, Kaurismäki can be seen as something of a Taisto, too.

The images, sounds, and dialogue that depict Taisto’s entry into prison are a portrait of stubbornness, but also stupid adherence to principle. Taisto lands in prison because he repeatedly does the wrong things, just as he drives across a snowy landscape from northern to southern Finland in a Cadillac convertible with the top down, because he cannot operate the roof. He gets mugged and robbed. He gets swindled. He gets arrested and thrown in prison. He allows his friend Mikkonen to take a risk that leads to Mikkonen’s death. Why does Taisto do all the wrong things? It is not a matter of naïve innocence and misplaced trust, for Taisto knows how to work, how to get up from a knockdown, and fire a handgun. What we have is inertia, a displaced man whose habits and ways are ill-suited to the world he inhabits, but who slowly refashions himself to inhabit a new social world. This conflict between habit and inhospitable social world recurs in Kaurismäki’s cinema thematically, through the director’s typically displaced characters, but also aesthetically, through Kaurismäki’s particular interpretation of the history of cinema aesthetics. His films are continually concerned with adaptation and coping. The negotiation between habit and social world also figures in the mode of production of Kaurismäki’s films, from their circumscribed budgeting practice to the stylised anachronisms of the films’ marketing material. Kaurismäki has stubbornly stuck to a filmmaking practice that is at once readily recognisable in its connections to underground filmmaking and auteur filmmaking, yet distinct in its adaptation of principles from these. These elements and practices engage in dialogue with current cinematic, cultural, political, and not least economic discourses, but use the past to resist assimilation to these discourses, seeking to push them in alternative directions – an argument already developed in our discussion of ironic bohemianism. This stubborn attitude creates a remainder, something which cannot be absorbed or assimilated by the discourses critiqued. We see this remainder in Taisto’s blank but animated look, his hunching gait, his clumsiness, and dumb luck, as well as the characters Nikander in Shadows in Paradise, Henri in I Hired a Contract Killer, M in The Man Without a Past, and Koistinen in Lights in the Dusk.

A compelling account of the remainder as relevant to nostalgia is suggested by Michel de Certeau’s notions of everyday life as practice, poetics, and tactics. Certeau’s abiding question is similar to the one raised continually in Kaurismäki’s films: how do subjects persist within social systems that aspire to determine subjective identities and practice? In asking this question, Certeau’s thought differs from theorists like Marx, Freud, and Foucault, and their many interpreters, whose theories emphasise how social forces and relationships constitute modes of control, determination, and subject formation. In contrast, the fundamental outlook in Certeau’s thought concerns resistance, as aptly described by historian Nathalie Zemon Davis:

Certeau developed a distinctive way of interpreting social and personal relations. In contrast to those who described societies by evoking what he called homogeneities and hegemonies – what unified and controlled them – Certeau wanted to identify the creative and disruptive presence of ‘the other’ – the outsider, the stranger, the alien, the subversive, the radically different – in systems of power and thought. He found it not only in the ways people imagined figures distant from them … But also in behaviours and groups close to home, in the ever-present tensions at the heart of all social life, whether in schools, religious institutions, or the mass media. (2008: 57)

The ever-present tension’ Davis identifies arises from practices like walking through the city, narrating, reading, and ultimately decaying and dying, all of which resist and transform engineered systems, technologies, and institutions that constitute modern forms of social order. Within everyday life, Certeau famously argues, there are many ways people adapt and repurpose determinative forces such as market and state, and it is through these practices that past and present intertwine. Certeau’s analysis focuses on the notion of contested spaces that are also part of Elsaesser’s analysis.

One of the dangers in Certeau’s thought is its amenability to exaggeration and romanticisation of quotidian forms of resistance. In a book on Certeau’s poetics of the everyday, Ben Highmore writes that ‘for the most part, responses to Certeau’s work have opted for a limited focus, considering only those aspects of his work that evoke daily practices of guerrilla-like and subversive opposition, ignoring those practices perhaps more “everyday”, that connect with memory, stubbornness, and inertia’ (2006: 103). Highmore goes on to point out that there are several overlapping categories through which Certeau distinguishes between everyday practices: the hidden, the multiform and extensive, the devious, and the stubborn. The hidden and stubborn character of everyday life practices in Certeau’s theory figure all too little in most discussion, suggests Highmore, yet it is in these dimensions that Certeau’s analysis is most subtle, and most relevant to Kaurismäki’s nostalgia. The hidden and stubborn practices involve the adaptation and modification of quotidian ways to function in capitalist modernity. The shopkeeper who runs a for-profit enterprise, but does so as a means of engaging with a particular group within a city. The adaptation of fast-food restaurants, airports, and office spaces to serve their employees’ needs, rather than customers. Taking these practices as an object of study avoids assuming a binary opposition between capitalist modernity and community (see Highmore 2006: 111). The restaurant, the store, and the family meal cannot be separated from the late-modern capitalist system and its conflicts, but can also sustain signifying practices which obdurately differentiate and sustain these activities. In these hidden and stubborn practices we see the interpenetration of competing claims, which are hybrid and subject to negotiation. So, for example, the store is both a for-profit enterprise and community gathering point. Or to turn to the films, the restaurant in Drifting Clouds involves business, fantasy, nostalgia, style, and humour, which cannot be parsed into singular, homogeneous units of past and present, mainstream and unique. Here again we also find Elsaesser’s double occupancy, which concerns the ongoing negotiation over such competing claims. In capturing hidden and stubborn aspects of quotidian practice, Kaurismäki’s films render nostalgia an affective node of agonistic claims and questions, rather than reducing nostalgia to an object to be depicted or a narrative to be disrupted.

Taisto (Turo Pajala) finally gets an industrial job while in prison in Ariel (1988) (used with permission of Sputnik Ltd.)

A good example of everyday nostalgia, the attitude it involves, and the relevance of Certeau are made evident in Taisto’s fashioning of a ring for Irmeli while in prison. Why does Taisto make a wedding band from scrap metal? What in his past causes him to take such risks to complete this symbolic task? It is a strange choice, insofar as the diegesis suggests that Taisto’s only family life has been difficult. Taisto witnesses his father’s suicide without a tear, and he doesn’t hang around for the funeral. The film tells us nothing about his mother or family. Taisto resembles Iiris in The Match Factory Girl to a degree, for Taisto’s wedding band calls to mind Iiris’s response to her bleak family life. In response to crushing family circumstances, both cling to romantic fantasies. There are no happy families in Kaurismäki’s films. Yet his families believe they can bend institutions like marriage, prison, the law, and the market to their needs – and they usually do, just a little. They adhere to these beliefs through habit, material practices, and the fashioning of objects – like Iiris’s taffeta dress – which maintain a modicum of hope.

In Taisto’s case, the ring is nostalgic, for it gives form to an idea of love which has no place or image in the narrative of the film, which is dominated by the legal order of the state. The ring defies the state in an appeal to an extra-legal, moral order, yet Taisto and Irmeli’s marital aspirations also depend on the state’s recognition of their union. They go to the magistrate to marry them after Taisto escapes from prison. In this tiny struggle we see precisely how nostalgia matters: memory and habit contest new or current practices by raising questions about the latter’s rationale, thereby calling for alternatives. Yet these questions are introduced within the practices and institutions of the system. To be sure, while heterosexual couplehood as narrative closure can be read allegorically as a new beginning, the hero going off into the sunset, it can also be seen as ‘confirmation of social exclusion of those not empowered by romance and compulsory intimacy’, as Anu Koivunen has pointed out (2006: 141).

Another way to see this episode unpacks another allegorical layer, concerning Kaurismäki’s relationship to cinema. Certeau would arguably describe Taisto’s fashioning of the wedding band in terms of ‘la perruque’, or the wig. By this term Certeau means neither theft nor malingering, but workers’ covert use of their employers’ tools or surplus resources in symbolically important projects.

The worker who indulges in la perruque actually diverts time (not goods, since he uses only scraps) from the factory for work that is free, creative, and precisely not directed toward profit. In the very place where the machine he must serve reigns supreme, he cunningly takes pleasure in finding a way to create gratuitous products whose sole purpose is to signify his own capabilities through his work and to confirm his solidarity with other workers or his family through spending his time in this way. (1984: 24–5; emphasis in original)

In la perruque, suggests Certeau, resistance occurs when the worker uses time in a way that has no motivation in the economic logic that commodifies workers’ time as labour power. In using his time for non-economic relationships, whose rationale is not profitability, the worker finds motivation for his activity in a contrasting moral order. Just as the beautiful camera cannot be explained as an economic choice, ‘the wig’ cannot be explained by economic relationships. By juxtaposing Taisto’s fashioning of the ring with his unhappy search for work and imprisonment, Ariel establishes a contrast that makes evident coexisting moral and legal orders, which make divergent claims on social spaces and institutions, which in their turn find their rationale in discrete temporalities. The contrast also finds a particularly clear expression in the later film The Man Without a Past, when the guard Anttila says, ‘the state does not sin’. Indeed, sin belongs to the moral order to which Taisto and other characters in Kaurismäki’s films appeal, and the state is premised on a legal order. Yet they coexist, and we understand Anttila’s humorous metaphor. These films stage precisely the conflicts of double occupancy we have been tracking.

Narrative instances of la perruque and everyday nostalgia recur throughout Kaurismäki’s films, often creating contrasts that put the focus on practices and objects that exist within orders to which they have ambivalent yet tenacious relationships. The characters in the films continually duck company rules and state laws in the interest of helping friends and confirming solidarity with others. In the early films written by Aki Kaurismäki and directed by his brother Mika – such as The Liar and The Worthless – Ville Alfa disrupts not only employment situations, but rule-bound settings of all kinds. The relationship between the manager Vladimir and the band members of the Leningrad Cowboys stages the same sort of resistance. We see a recurrence of la perruque in Drifting Clouds, in which spouses, siblings, and friends understatedly disobey workplace rules to help one another out – giving free rides, free meals, and free passes to the movies. The topos returns in Lights in the Dusk, when the security guard Koistinen seeks to impress a romantic interest by defying workplace rules, bringing about his own misfortune in a way that suggests the dubious status of morally motivated action in a market-driven society.

Taisto surreptitiously fabricates a ring for Irmeli, in Ariel’s instance of la perruque (used with permission of Sputnik Ltd.)

Certeau helps us see the extent to which these instances of la perruque are in fact subtle conflicts over a socio-political ethics and the moral order that underpins it, which also carry a temporal dimension.

Into the institution to be served are thus insinuated styles of social exchange, technical invention, and moral resistance, that is, an economy of the ‘gift’ (generosities for which one expects a return), an esthetics of ‘tricks’ (artists’ operations), and an ethics of tenacity (countless ways of refusing to accord to the established order the status of law, a meaning, or a fatality) … The practice of economic diversion is in reality the return of a sociopolitical ethics into an economic system. (1984: 26–7)

By withholding cooperation in the workplace, a worker differentiates his activity by justifying it with an alternative ethos to the one that predominates in the workplace. He opts out of the economically motivated measure of his subjectivity in terms of time. The economy of the gift depends on relationships premised on memory and future acts, rather than on measurement of value in terms of time spent.