An unusual commercial betrothal was proclaimed with sober understatement on September 21, 2012. Under the prosaic headline “Sotheby’s Signs Deal with Beijing Company,” a brief report in The New York Times explained that the world’s premiere auction gallery had entered into a joint-venture agreement with a state-owned enterprise “to capitalize on the tremendous growth in the Chinese market.” Thus in partnership with the Beijing GeHua Art Company, Sotheby’s announced that it would shortly launch the first international auction house in mainland China. The two companies agreed to share tax-exempt storage facilities, with Sotheby’s providing a $1.2 million investment as dowry. As a Sotheby’s press release elaborated, “China and its growing class of collectors has been the single most attractive growth market for the company,” leading to an agreement it described as “unique and groundbreaking.”

It was indeed. Here was the nominally Communist People’s Republic actively promoting the least proletarian of pastimes: auctioning fine arts to a proliferating breed of princely millionaires. True, the Sotheby’s deal was but one more example of China’s rightward leap from primal Maoism to state-promoted capitalism. Yet to those who professionally track the tectonic shifts in the Chinese art market—whether as collectors, dealers, or scholars—there were less obvious signals as well. For upward of a decade, Beijing has also sought the recovery of art treasures pillaged from China during chaotic times past. Simultaneously, the People’s Republic has strengthened legal measures to curb wholesale looting and the illicit export of ancient art. To that end, in 2009 Beijing secured from Washington a largely unnoticed yet significant pact barring the importation of a wide range of antiquities, including monumental sculpture and wall art at least 250 years old.

So why would China also encourage a bull market in antiquities that most analysts contend also fuels the pillaging of its patrimony? What does all this say about the changing prism through which Beijing’s leaders view the Maoist era and its once-scorned imperial precursors? And how will the People’s Republic deploy its new and surprising leverage as host to an exploding art market (rivaling New York and London in 2011–12)? Taken together, Beijing’s cultural strategy seems a compound of opposites: a thirst for profits, a strong bid for foreign applause, but also a determined effort to score domestic points with get-it-back populism.

Clearly visible in this eighteenth-century engraving is the Zodiac Fountain and its twelve animal heads below the Hall of Calm Seas at Yuanmingyuan.

Thus in approving the Sotheby’s deal, Beijing may also be searching for an insider’s advantage in its ongoing campaign to recover prized artworks that were seized in times past as the spoils of war. The campaign was presaged in 2000 by China’s offstage role in a lavish “Imperial Sale” promoted in Hong Kong by Sotheby’s and Christie’s. Among the latter’s major offerings were two bronze animal heads (an ox and a monkey), while by coincidence Sotheby’s put on the block a bronze tiger head. These were three of twelve animal heads that once adorned a zodiac fountain in Peking’s Yuanmingyuan, or Garden of Perfect Brightness, the Summer Palace of the Qing emperors, from which they were very likely filched by Anglo-French troops in 1860 during the looting that concluded the Second Opium War. China’s Bureau of Cultural Relics formally asked both auction houses to withdraw the suspect bronzes, citing the UNESCO convention on cultural property.

Beijing’s protest did not persuade executives at the two auction houses, whose press aides noted that the bronze monkey had been sold previously by Sotheby’s in New York in 1987 without a murmur; ditto the ox in London in 1989. Yet in a token of changing times, Hong Kong residents otherwise critical of Communist rule joined in clamorous protests over the pending “Imperial” sale. Demonstrators shouted, “Stop auction! Return Chinese relics to Motherland!” But the sale went forward.

In a symmetrical finale, the three zodiac bronzes were repatriated in a bidding war won in 2000 by the China Poly Group, a corporate offshoot of the People’s Liberation Army, also a dealer in arms and real estate. The monkey and ox fetched more than $2 million at Christie’s, and the tiger went under the hammer for $1.8 million at Sotheby’s. This was the first time that agents of the Chinese government competed at public auction to recover art and antiquities. “Historic events took place this week,” Souren Melikian reported in The International Herald Tribune, “that will have incalculable repercussions in the international approach to cultural monuments.” A long war over title to the zodiac relics was under way. As before, Melikian, a veteran monitor of the global art market, assessed its vibrations astutely.

Following their triumphal return to Beijing, the three heads were showcased in the newly created Poly Art Museum, thereafter the chosen refuge for trophy art recovered from private collections. This represented a sharp reversal of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–76), when roving gangs of Red Guards smashed vitrines and bullied curators with the encouragement of Chairman Mao. It was among many turnabouts in the contorted path of Sino-Communism. Who could have imagined that the world’s largest standing army would become a champion of classical culture, one of the “Four Olds” reviled only yesterday? Or does the change simply confirm an old, shrewd peasant saying: “Be like the bamboo; it bends with the wind but stands straight after the storm passes”?

Thus even as screaming youngsters denounced the “Four Olds,” the Great Helmsman himself extolled archaeologists for bearing scientific witness to China’s glorious past. With Mao’s support, a united China, no longer beset by foreign or domestic violence, could finally undertake extensive excavations. A thousand lawful shovels were loosed on the past, crowned in 1974 by the unearthing of an entire army of terra-cotta warriors. Accidentally discovered by a farmer near the ancient capital of Xi’an, the life-size soldiers proved to be the afterlife bodyguard of China’s first emperor, an autocratic modernizer who reputedly burned books and dissident intellectuals and then gave his dynastic name (Qin, pronounced like chin) to a new empire. The discovery, with its sardonic overtones, fired instant interest at home and abroad. Specimen recruits from the frozen army were posted abroad to publicize a succession of exhibitions, arguably China’s most benign foreign invasion.

Thereafter, excavations flourished. So did the market for Chinese antiquities. Abroad, collectors evinced a seemingly insatiable appetite for most genres of art originating in China (calligraphy excepted). More surprising was the vibrant demand within the People’s Republic. By 2005, art and antiquities sales at China’s eighty-odd domestic auction houses reportedly exceeded $1.5 billion, double the previous year’s total. In the reckoning of James Cuno, head of the J. Paul Getty Trust, it was twenty-five times Sotheby’s and Christie’s combined U.S. sales of Chinese art the same year. (It later developed that the totals included buyers who did not pay for what they bid.) And Cuno’s calculation did not include the local galleries and curio shops that sprouted everywhere in mainland China. By 1980, almost $2 billion worth of art had been sold at Chinese auctions, with starred works for the most part purchased by private bidders. As China’s economy grew, so did the art market. In the reckoning of Forbes magazine, the number of Chinese billionaires rose from 64 in 2009 to 115 the following year, an 80 percent annual increase. Sales soared for fine arts in every category. In 2010, the People’s Republic seemingly surpassed New York and London as host to the world’s leading fine arts market, accounting for 33 percent of global sales, compared to 30 percent for the United States, 19 percent for the United Kingdom, and 5 percent for France (as calculated by Artprice, a Paris-based monitor). The news was blazoned by China Today, a glossy, quasi-official Beijing monthly. Indeed, the journal noted in March 2011 that of the ten highest bids ever recorded at auctions for Chinese art, only one was placed abroad (in London in 2005, for a Yuan dynasty sculpture)—an “epochal change” from leaner days past. The boom has since fluctuated, unpaid bids inflated totals, and in 2012 China slowed to a second-place finish behind the United States. Nonetheless, in ways Chairman Mao (who died in 1976) might not have imagined, his maxim that the past should serve the present has been richly realized.

Yet from an archaeologist’s vantage, the enthusiasm for collecting antiquities among newly minted billionaires has a dismaying underside. As never before, thousands of remote sites have been subjected to “an unbridled wave of clandestine digging,” in the words of Melikian. He was among the first to report (in November 1994) that “something funny” was happening in East Asian markets: “In the last few years, the flow of antiquities handled by ‘clandestine’ diggers who sell them in the Hong Kong art trade has not just been torrential, as it has been since the early 1980’s. It increasingly includes works of art of a rarity that one expects to come out of the most important archaeological sites.” True, this was a clandestine criminal enterprise. But Melikian took note of a Han-period bronze sculpture recently on the block in Hong Kong: “How ‘clandestine’ can you be, carting a 26-inch chunk of metal overland, all the way to the coast, in a state where policing is reputed to be vigilant?” (Note: both before and after the reversion of Hong Kong to China in 1997, auctioneers in the former British colony have operated with greater freedom than on the mainland.)

How then has the People’s Republic responded to what Melikian two decades ago described as “the reckless rape of its past”? Chinese archaeologists have consistently echoed his alarm. “It really is devastating to see what is happening,” Professor Wei Zheng of Peking University recently told a correspondent from The Guardian. “Archaeologists are simply chasing after tomb raiders.” As elaborated by his colleague, Professor Lei Xingshan: “We used to say nine out of ten tombs were empty because of tomb raiding, but now it has become 9.5 out of ten.” Chinese excavators pointedly cite a peasant catchphrase, “To be rich, dig up an ancient tomb; to make a fortune, open a coffin.”

The reckless rape continues, notwithstanding a century of explicit prohibitions. In 1913–14, the newborn Republic of China introduced laws banning the removal of “ancient objects,” followed by still stronger legislation in 1930. These measures were reinforced in 1950 by the People’s Republic, which in its first years established a Bureau of Cultural Relics to ensure compliance. Even more stringent legislation in 1961 widened the definition of protected artworks to include objects “which reflect the social system, social production and the life of society in all periods.” This was followed by a 1982 cultural relics law, designating all antiquities found in caves and tombs as national property and adding a new corollary: legal private ownership was henceforth permitted for works “handed down from generation to generation which belong to collectives or individuals.” In effect, this constituted a tacit acknowledgment (as James Cuno and others have noted) that state-run auctions were already selling confiscated art from government warehouses to aspiring collectors, the way led by the privileged offspring of the party elite.

Granted, China’s preservationist tasks are truly monumental. By official count (1993), the People’s Republic possesses 350,000 historic sites—tombs, palaces, caves, and temples—mostly unexcavated, dating from the Bronze Age (circa 3500 BCE) through a succession of imperial dynasties until 1911. No soil anywhere harbors as rich a legacy. Creditably, Beijing has substantially increased funds for security, energized in part by cultural tourism, led by the surge of visitors to Xi’an and its terra-cotta army. True as well, indigenous looters are on occasion exposed and punished. It made headlines a decade ago when government agents identified a group of Buddhist statues pilfered from Chengde’s historic temple complex (a World Heritage Site) that Christie’s was about to auction in Hong Kong. The dealer owning the relics was detained; he insisted the looters had lied to him about their origin, and he was released after restoring the statues to state custody. Subsequently, the local official responsible for guarding the site was tried, found guilty, and executed for stealing 158 artifacts, said to be the largest relic heist since the founding of the People’s Republic. Yet in a May 2003 dispatch on the aborted sale, John Pomfret of The Washington Post also took note of a wider scandal. An anonymous market hand told him that despite the heightened security, “The looting of cultural treasures in the past twenty years has exceeded the destruction of relics during the Cultural Revolution.”

Looting is not solely responsible for this destruction. Preservationists contend that it stems as well from China’s headlong drive to electrify, irrigate, and modernize. They cite the Three Gorges Dam, completed in 2009, which flooded some four hundred square miles, the goal being to provide new sources of energy to a distressed region while taming the erratic waters of the Yangtze River. Yet state-funded salvaging of doomed sites was so perfunctory (critics claim) that the soon-to-be-engulfed tombs became a pillagers’ paradise. Elsewhere, in such richly layered urban centers as Beijing, Shanghai, Kashgar, Lhasa, and Xi’an, historic shrines and neighborhoods have been razed with relentless zeal to make way for high-rise housing, soulless office buildings, and stereotypical stadiums.

As these episodes suggest, it is less ideology than opportunism that informs Chinese cultural policy. From Deng Xiaoping’s tenure onward, Beijing’s cultural cadres have discreetly diluted Maoist dogmas with the modernist views of a younger generation, along with the claims of a buoyant art market and the bonus of favorable foreign opinion. This amalgam seemingly accounts for Beijing’s changing attitude to Western-influenced paintings, films, photography, architecture, and music. Few foreigners have tracked the transition more closely than Michael Sullivan (long the doyen of British Sinologists prior to his death in 2013), who from the 1940s onward befriended, wrote about, and collected the works of living Chinese artists. This was his judgment as of 2001 (in Modern Chinese Art): “Much of the best work of the 20th century has political resonance, overt or oblique, that gives it a particular edge or vitality. . . . New, if erratic, freedoms, the birth of free enterprise, commercialism, and the interest of foreign critics and art galleries, began to create an art world, chiefly in Beijing and Shanghai, that looked more and more international—in style, if not in content—while new forms of art, such as performances, installations, happenings, were a stimulus to hundreds of young artists clamoring for attention.”

Moreover, overseas fascination with China’s effervescent art world proved an unexpected asset in post-Maoist diplomacy. With palpable symbolism, Beijing in 2002 opened its first cultural center in a Western capital: in Paris, on the banks of the Seine. The new center’s offerings, from Bronze Age sculptures to conceptual art, proved so popular that its stone building (once home to Napoleon Bonaparte’s descendants) acquired a modern annex in 2008, tripling floor space from 1,700 to 4,000 square meters. Other countries courted by China have likewise been awarded Confucius cultural centers. In 2011, nine such centers sponsored 2,500 activities for 600,000 visitors (by Chinese count). Ten more centers are planned. So recounted the Beijing-published China Pictorial (October 2012) in a thematic issue titled “A Booming Cultural Decade.” The journal lauded China’s recent discovery of such “soft power,” explaining Beijing’s tardy entry into cultural diplomacy with an egregious understatement: “After a long period of isolation, China lacked elements to represent modern culture beyond its borders.”

Yet China’s cultural offensive has a second, less commonly publicized front. Commencing in the 1990s, Beijing’s arts officials turned afresh to long-standing grievances concerning the illicit removal of perceived art treasures. Here, finally, was a cultural issue on which the People’s Republic could rise above profit-tainted pragmatism to loftier grounds of principle. Nationalists and Communists alike look back indignantly to a “Century of Humiliation”(1840–1949), when China was bullied by foreigners, forced to submit to unequal treaties, sliced into zones that privileged Western traders and missionaries, and, upon losing the two Opium Wars, compelled to permit the legal importation of a soul-destroying drug.

These grievances spring from a widely agreed-upon history, but Western accounts stress a complicating counterfactual: Imperial China was itself a feudal fossil, notorious for its corruption, incompetence, and self-wounding defiance of common diplomatic usage. Moreover, following the empire’s collapse in 1911, the new Republic of China’s principal adversaries were homegrown warlords, indigenous Communist insurgents, and non-Western Japanese invaders. Still and undeniably, Westerners for more than a century evinced more zeal than scruple in acquiring Chinese masterworks, especially the huge friezes and monumental sculptures displayed in major North American museums. As carefully phrased by a Detroit curator, Benjamin March, in China and Japan in Our Museums (1929), the first comprehensive inventory of American holdings: “Probably there is no thoughtful collector in America today who does not deplore the means by which some of his most valued treasures became available, at the same time that he cherishes and reveres them as great works of art of universal moment.”

Acting on this shared acknowledgment, Beijing in 2005 established a Cultural Relics Recovery Program to identify museum-quality art taken from China between the years 1860 and 1949. Chinese officials cite a UNESCO estimate that no fewer than 1.67 million Chinese relics are possessed by no fewer than two hundred museums in forty-seven countries. It is also estimated that ten times that total are now in private collections. As phrased by Xi Chensheng, an advisor to the Bureau of Cultural Relics, “Most were either stolen by invading nations, stolen by foreigners, or purchased by foreigners at extremely low prices from Chinese warlords and smuggled abroad.” To obtain corroborating evidence, China next dispatched teams of investigators to examine the provenance of East Asian art in leading Western museums, libraries, and private collections.

These visits supplemented Beijing’s campaign, begun in 2004, to obtain from Washington an agreement to restrict the importation of Chinese antiquities, similar to existing bilateral accords with Italy, Guatemala, El Salvador, Peru, Canada, Cyprus, Cambodia, and Mali. China’s request was challenged by prominent museum directors, scholars, dealers, and collectors, on four broad grounds: (1) that Beijing had not taken adequate measures to protect its own ancient sites; (2) that priceless Chinese works were in fact safely preserved abroad during East Asia’s turbulent years; (3) that the display of great works in encyclopedic galleries affirmatively stimulated interest in Chinese art; and in any case (4) that the People’s Republic itself was actively encouraging a domestic market in antiquities, thereby fueling rampant looting. These contentions were elaborated in essays collected and edited by James Cuno in Whose Culture? (2012).

Nonetheless, in 2009 the State Department announced its approval of a bilateral accord that substantially addresses Beijing’s concerns. Its appended five-year Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) “restricts the importation to the US of cultural and archaeological materials from the Paleolithic through the Tang Dynasty (75,000 BC–AD 907), as well as monumental sculpture and wall art at least 250 years old. . . . Such archaeological materials can only come to the US if accompanied by a valid export permit or other appropriate documentation from the Chinese government.”

As of this writing, with one exception discussed below, China has not formally sought the restitution of any major disputed works in foreign museums. Rather, it has used its market power to highlight egregious episodes of pillaging. The one exception is the loot taken in the ravaging in 1860 of the imperial garden estate Yuanmingyuan, the site of the Old Summer Palace, by Anglo-French armies besieging Peking in the final phase of the Second Opium War. On the war’s 150th anniversary, the Chinese called for the return of everything stripped from the emblematic imperial residence. In Chinese eyes, it was an act of vandalism comparable to Lord Elgin’s hacking the marble carvings from the Parthenon a half century earlier—and as it happens, the Briton who ordered its demolition was James Bruce, the eighth Earl of Elgin and son of the reputed despoiler of the Acropolis.

In truth, the elder Elgin earned his notoriety, whereas his son’s was thrust upon him. Great Britain in 1860 was still reeling from the muddled and anguishing Crimean War (1853–56), followed by the two-year rising in India known as the Great Mutiny. Among the five thousand British troops in China were many who served in one or both prior conflicts, sharpening appetites for spoils. Moreover, the Second Opium War (1856–60) was fought as an embattled Chinese regime also coped with the Taiping Rebellion (1845–64), an apocalyptic uprising in the south, generally considered the modern era’s deadliest civil war, that claimed as many as twenty million lives. A further complication was Britain’s alliance with Emperor Louis-Napoléon’s France. As in Crimea, it proved a sticky partnership. Its chief defender in Parliament was the aging Whig prime minister Lord Palmerston, whose jingoist language drew withering fire from such leading Liberals as W. E. Gladstone, Richard Cobden, and John Bright. Taken together, their heated exchanges about wars of choice versus wars of necessity, or about imperial hubris versus Britain’s civilizing mission, would in our day make most politically literate Americans feel at home.

All these conflicting themes coalesced in the 1860 destruction of the vast Yuanmingyuan, situated around a dozen miles northwest of Peking (then already a metropolis, with a million or more inhabitants). In size, elegance, and prestige Yuanmingyuan was far more than a playground for six generations of Manchu rulers. It was to China what Versailles is to France, arguably twice over. (In fact, its buildings included those designed for the Qianlong emperor in the eighteenth century, after he saw images of Versailles.) Its inner core comprised a thousand or so acres of immaculate gardens, sparkling ponds, and humpbacked bridges, within which were cunningly sited a fairyland of palaces, temples, pagodas, libraries, and theaters, plus ateliers for scientists, pavilions for philosophers, and a make-believe village for shoppers. In design, Yuanmingyuan blended Chinese traditions with European pseudo-Baroque, the latter most evident at the Palace of Calm Seas, whose entrance embraced an elaborate zodiac fountain and water clock. As designed by the Jesuit missionary Giuseppe Castiglione, long a resident artist in the Manchu court, the twelve animals in the Chinese zodiac were arrayed around the fountain. At noon, all spouted water in unison; otherwise each gushed at its assigned moment in a twelve-hour cycle.

Here indeed was Coleridge’s stately pleasure dome, as conjured by the poet in his narcotic dream, its gardens bright with sinuous rills, its forests ancient as the hills, its walls and towers girdled round, its goldfish flashing in its ponds, where, warningly, “The shadow of the dome of pleasure / Floated midway on the waves.” (The poem was actually inspired by the Yuan dynasty summer palace, which was farther north.) As thousands of Anglo-French troops found when they burst into the regal quarters on October 7, 1860, it was also filled with portable and royally elegant riches: jewelry, porcelain, paintings, sculpture, illuminated books, every imaginable kind of furniture, silken robes, headgear, and even Pekinese dogs (then unknown to Europe).

With a whoop, both armies carried out a command to destroy Yuanmingyuan, as unilaterally ordered by a reluctant Lord Elgin, the British high commissioner, in which French troops took willing part (though their commander, General Cousin de Montauban, tried to distance himself from the resulting melee). This drastic step was meant to drive home allied anger after Chinese imperial forces reportedly seized, tortured, and killed twelve members of a European diplomatic delegation (also including Thomas Bowlby, a correspondent for The Times), a flagrant violation of the codes of war as understood by Europeans.

That Elgin became their avenger was existentially ironic. He was not a fan of Lord Palmerston, whose China policies he had privately termed “stupid.” He deplored “commercial ruffianism,” and when ordered to legalize the sale in China of opium grown in India, he wrote in his diary, “Though I am forced to act almost brutally, I am China’s friend in all this.” And on being instructed in 1859 to attack and occupy Peking, he again privately dissented: “The general notion is that if we use the bludgeon freely enough we can do anything in China. I hold the opposite view.” Yet sadly for Elgin, he is indelibly associated with a deed of imperial plunder that, like the ominous shadow in Coleridge’s poem, still lingers over China’s haunted pleasure dome. So what actually did happen?

Despite more than a century of postmortems, it is still unclear which army ignited the rampage, how the spoils were divided, and which treasures ended up where. In analyzing conflicting accounts, the University of Chicago’s James L. Hevia attributed their divergence to national rivalries, questions of honor, and ongoing criticisms of the pillaging. “Neither the British nor the French, it would seem,” Hevia concludes in his 2005 analysis, “wanted to be held responsible in the eyes of the other, and if a scapegoat were needed, the Chinese were conveniently at hand.” Such was Lord Elgin’s own justification: he insisted that the destruction of the Yuanmingyuan was meant to send an imperative message to a vacillating emperor and his scheming advisors, not to the nonoffending Chinese people. In his words, his purpose was “not to pillage, but to mark by a solemn act of retribution, the horror and indignation with which we were inspired by the perpetration of a great crime.”

Instead, Elgin’s order united the emperor with his own people in shared outrage over (in their eyes) the pointless and humiliating devastation of a national treasure by foreign devils. As many as two hundred buildings were torched or leveled, and everything of value that could be taken, was taken (the French complained that the British had the unfair advantage of possessing cavalry horses capable of hauling the heavier prizes). Concerning the totality of destruction, there is ample and authoritative testimony. “When we first entered the gardens, they reminded one of those magic grounds described in fairy tales,” recalled Colonel Garnet Wolseley, a decorated veteran of campaigns in Crimea and India. Yet on October 19, “[W]e marched from them, leaving a dreary waste of ruined nothings.” (Wolseley later became the imperial specialist in small wars, immortalized as “The Modern Major-General” by Gilbert and Sullivan.) Another credible witness is Captain Charles Gordon of the Royal Engineers, soon to be known as “Chinese” Gordon for his valor in helping the Manchus quell the Taiping rebels. “You can scarcely imagine the beauty and the magnificence of the buildings we burnt,” he wrote to a friend. “It made one’s heart sore to burn them. . . . It was wretchedly demoralizing work for an army. Everybody was wild for plunder.” (Three years later, while commanding China’s Ever Victorious Army, Gordon resigned to protest the mistreatment of war prisoners; in 1885, he perished at the hands of Sudanese jihadists, thereafter becoming Gordon of Khartoum.)

For their part, French witnesses also expressed astonishment at the magical beauty of the imperial oasis, but distinguished between the demolition of buildings (wholly regrettable) and pillaging (arguably the victors’ prerogative). These views are elaborated by Comte Maurice d’Hérisson, an interpreter for the French forces who maintained that he remained an onlooker as the plunder proceeded. As excerpted by the German author Wilhelm Treue in Art Plunder (1960), the count asserts that the original plan was to appoint three British and three French commissioners to identify precious objects for Queen Victoria and Napoleon III as their respective shares of the customary spoils of war, then to divide the remaining booty equitably among all ranks. However, on the first afternoon, as goods were being carted from the principal royal residence, this is what happened:

The crowd which collected to watch these proceedings was composed of French and English foot soldiers, riflemen, gunners and dragoons, of spahis, sheiks and Chinese coolies too, all watching with staring eyes and lips parched with greed; suddenly a rumor spread in all the various languages: “When they’ve had the best, it’ll be our turn!” “To hell with that! We want our share of the cake. We’ve come far enough for it. Eh, Martin? Eh, Durand?” They laughed and barged forward—discipline began to give way. . . . Covetousness suddenly aroused among the Chinese a sense of patriotism; they told themselves that the hour of revenge had struck, and that—if I may be forgiven the expression—it would be the bread of life to rob the Manchurian dynasty, and not leave the whole windfall to the barbarian invaders.

As soon as the soldiers heard the news, of course in a greatly exaggerated fashion, anxiety gave way to fury. First, they said, “The Chinese want to bag the lot!” and then, “The Chinese are going to burn the whole place down!” A wild mob surged around the gates. The sentries were pushed aside, and the whole crowd, soldiers and civilians, poured in on the heels of the company that had been summoned to expel the intruders. At once, everyone took what he liked.

After the wild crowd surged through the vast Yuanmingyuan grounds, it appeared to Comte d’Hérisson that the British were better disciplined, having quickly instituted an organized system for dividing the spoils and employing carefully recorded daily auctions, while the French seemed to act impulsively on their own. He then offered a moralizing verdict in the immemorial tradition of cross-Channel badinage: “The English, of course, are well used to having their heel on the neck of Asiatic peoples; and it must not be forgotten that their army is composed of mercenaries who regard plunder as one of the elementary principles of war.” Moreover, he added as a parting jab, had the British preceded the French to the Summer Palace, “Certainly, they would not have lost a moment in dispossessing His Imperial Majesty [i.e., Napoleon III] of his goods.”

Then as now, others in France rose above nationalist jeering. The most oft-quoted Gallic judgment required but a single sentence. On learning of the behavior of the Anglo-French armies in Peking, Victor Hugo (who loathed Louis-Napoléon) dispatched an open letter to the French press. “We call ourselves civilized, and them barbarians,” Hugo wrote from his self-imposed exile on the Channel Islands, “and here is what Civilization has done to Barbarity.” (For his efforts, the modern-day Chinese have bequeathed the French literary giant a statue in Yuanmingyuan.)

Moral judgments aside, it is indisputable that, after the pillage, whole shiploads of porcelain, jewelry, furniture, paintings, clothing, swords, and statuary sailed westward. The spoils presented to Emperor Louis and Empress Eugénie Napoleon still form the core of the purpose-built collection of Chinese art at the Fontainebleau Château. In London, among the highlights of the 1861 auction season (as in many future years) were Oriental treasures bearing the premium label “From the Summer Palace.” For her part, Queen Victoria was presented (among other spoils) with a cap said to have been worn by the Chinese emperor, and with a frisky Pekinese dog, the first of its breed known to reach the West. The dog’s apt name was “Looty,” appropriately bestowed by Victoria herself.

Loot derives from the Hindi word lut, which in turn originates from the Sanskrit lotra, meaning “rob, plunder.” By 1800, the word found acceptance in its colloquial sense among Britons in both India and China, then went global following the two Opium Wars and the Indian Mutiny (as traced in Hobson-Jobson, the standard glossary of Anglo-Indian words). In short, the word loot is very much the offspring of Europe’s imperial era, as is the vexed matter of a conqueror’s right to the property of a conquered people. On the one hand, victors have claimed the right to the spoils of war, a prerogative stretched to the limit by Napoleon, who filled the Louvre with looted masterpieces from Italy, Central Europe, Spain, the Low Countries, and Egypt. On the other hand, the greedy plunder of conquered peoples has long emitted a nasty odor, as classically argued by Cicero in his scourging indictment of the takeaway Sicilian proconsul Verres.

Still, there were no codified laws of wartime morality in 1860. Customary norms served as a traditional brake on the limits of conquest, but these norms were ambiguous and nonbinding. In Europe, the void was addressed by the Dutch-born jurist Hugo Grotius, who proposed a global code following the devastating Thirty Years’ War. His proposal gained fresh impetus a century later with the publication in 1758 of Le droit des gens by the Swiss diplomat Emmerich de Vattel, who proposed establishing formal rules, binding on all belligerents, to protect the lives, rights, and property of both captured combatants and civilians trapped in occupied areas. In vain; so nebulous were the laws of war that protests of their violation remained wholly rhetorical.

Thus in 1814, when 1,500 British marines stormed Washington and torched the White House and the Library of Congress, the invaders were accused of grossly violating “the rules of civilized warfare.” Moreover, contended President Madison, the Britons demolished “monuments of taste and the arts” and thus evinced “a deliberate disregard for the principles of humanity” that could have provoked a war “of extended devastation and barbarism.” To which the British rejoined that their Major General Robert Ross, a veteran of the Peninsular Campaign in Spain, was rebuffed in his repeated offers to negotiate, and in any case that American armies invaded Canada four times, devastating entire towns near the frontier (episodes rarely mentioned during America’s own bicentennial observances of the War of 1812).

In short, hypocrisy, double standards, pious exhortations, appeals to nonexistent laws, and backstage bargaining were the rule as soon as the word loot entered diplomatic discussions during the apogee of the imperial era. By 1900 most of the world’s peoples and lands were under the dominion of fewer than a dozen nations—including the United States, a latecomer to the scramble for spoils, having just acquired Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico.

What this signified for China was presaged at a tumultuous Ecumenical Conference in April 1900 at Carnegie Hall in New York, attended by a thousand delegates from missionary societies across the United States. The opening ceremony included addresses by President William McKinley, former president Benjamin Harrison, and future president Theodore Roosevelt. Missionaries were “the world’s heroes,” McKinley told the delegates, because they “illumined the darkness of idolatry and superstition with the light of intelligence and truth.” Not only did these heroes spread the Gospel, but they also generated useful trades, promoted new industries, and encouraged the “development of law and the establishment of government.” They were, in effect (a phrase not heard then) nation builders. Nowhere were their efforts more needed or desired than in China. This was underlined by a concurrent missionary exhibit in the hall showcasing a profusion of Chinese objects, enriched by more than five hundred photographs suggesting both the grandeur and poverty of the Celestial Empire: the most attention given any foreign country at the conference.

This was the bright side of American perception of the world’s most populous nation. A less laudable side was evinced by Benjamin Harrison in 1888, when, upon accepting the Republican nomination, he endorsed immigration laws barring the entry of “alien races [i.e., Chinese], whose ultimate assimilation with our people is neither possible nor desirable.” This was a bipartisan view. The same year, Grover Cleveland, the Democratic nominee, described the Chinese as “an element ignorant of our laws, impossible of assimilation with our people, and dangerous to our peace and welfare.”

Chinese bafflement about such Western professions of superior virtue assuredly deepened in 1900, a year made memorable by the siege in Beijing (then called Peking by Westerners, but pronounced in Chinese as Beijing) that ended what was instantly known as the Boxer Rebellion. Viewed from America and Europe, the siege was essentially a morality play in which courageous Westerners triumphed over misguided barbarians intent on murdering innocent Christians. This basic narrative was recycled in contemporary press accounts, boys’ own fiction, Hollywood films (including a 1963 epic starring Charlton Heston and Ava Gardner), and in scores of memoirs by diplomats, soldiers, clergymen, and journalists. The latter were among the thousand or so non-Chinese civilians trapped in Peking’s Legation Quarter for two months until their rescue in August 1900 by a multinational rescue force, the first of its kind.

Dozens of Americans took a leading part in this resounding finale, their role underscored by President McKinley, who earlier the same year proclaimed his celebrated “Open Door” doctrine. The doctrine decreed that all nations were henceforth to enjoy equal access to China, overriding the spheres of influence wrested by Britain, Russia, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan. (Actually, observed George F. Kennan in his 1951 book American Diplomacy, the doctrine was a rhetorical gambit meant to assist McKinley’s forthcoming reelection; it proved neither new nor enforceable, Kennan contended, and after the U.S. annexation of the Philippines and Puerto Rico, “we set up discriminatory regimes, conflicting with Open Door principles.”)

The Boxer crisis in China ignited when a rebel movement called the Harmonious Society of Righteous Fists sprang up in the poor, densely populated northeast province of Shandong. The province’s treeless farmlands in 1897–1900 were parched by persistent drought even as its lowland areas were flooded by the Yellow River. This stricken area had been recently assigned to Kaiser Wilhelm II as Germany’s sphere of influence, prompting an influx of Christian missionaries, railway builders, urban developers, and brewers (to whom China’s most popular beer, Tsingtao, owes its origin). In 1897, two Catholic missionaries were murdered, and as reparation the kaiser demanded the right to build a new naval base and Christian churches with Chinese government funds. Otherwise, he vowed, the Chinese would feel “the iron fist of Germany heavy on their necks.” As these threats resounded, the imperial bureaucracy in Peking proved unable or unwilling to provide urgently required humanitarian aid.

This was the spark. Within months, the Boxers grew into a nationwide opposition militia whose fiercer recruits believed themselves invulnerable to bullets. The movement’s avowed mission was to expel or punish foreigners in general, and Christian converts in particular. In spring 1900, a year the Boxers welcomed as the new dawn of religious renewal, their numbers swelled exponentially. Though lacking coordinated leadership, writes Jonathan Spence in The Search for Modern China (1990), Boxers drifted into Peking, where they roamed the streets “dressed in motley uniforms of red, black, or yellow turbans and red leggings, with white charms on their wrists,” and began harrying, and sometimes killing, Chinese converts. Anxiety among foreigners turned to panic when the Boxers, having slain European engineers and missionaries, ripped up railway tracks, burned train stations, and slashed telegraph lines.

All this happened as Britain was mired in the Boer War (1899–1902), commencing with “Black Week,” during which legendary regiments were humbled by bewhiskered South African farmers. In the South Pacific, American forces were struggling to pacify the newly liberated Philippines and its unexpectedly ungrateful guerrillas. China, meanwhile, was still recovering from its losses to an upstart neighbor in the Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), which resulted in Tokyo’s seizing control of Korea. During the same years, Russian traders and Cossacks were consolidating their mastery of Manchuria, homeland of China’s ruling dynasty. Everywhere, it seemed, existing hegemons were under siege. Worried statesmen in Britain, America, and France reached anxiously for ways to reaffirm the West’s traditional martial vigor as a new century dawned.

Almost as a demon-sent gift, the Boxers materialized: the perfect foil for rattled Euro-Americans and a rising Japan. While Chinese authorities dithered, Boxers seized control of the streets surrounding Peking’s Legation Quarter. In June 1900, the aging Dowager Empress Cixi, grasping for popular support, rashly sided with the rebels, protesting that foreigners had been far too aggressive: “They oppress our people and blaspheme our gods. The common people suffer greatly at their hands, and each one of them is vengeful. Thus it is that the brave followers of the Boxers have been burning churches and killing Christians.” At this point, a thousand or so Westerners, together with their Japanese allies and around two thousand Chinese Christians, barricaded themselves in Peking’s well-defined Legation Quarter. Their quickly chosen commander in chief, unsurprisingly, was Sir Claude MacDonald, Britain’s minister to the Manchu court, an immaculately groomed, wax-mustachioed veteran of colonial wars in Egypt.

After the Boxers severed lines of communication, the diplomats and their families huddled alongside Chinese Christians. Behind the existing Tartar Wall (so-called) and improvised barriers, they braved sniper fire, disease, and hunger. No less imperiled was the Catholic congregation gathered in Peking’s Peitang Cathedral under the defiant and capable leadership of Bishop Pierre-Marie-Alphonse Favier. But there was no massed Boxer attack. Beyond Peking, in the walled city of Tianjin (then spelled Tientsin by the Americans and British), Boxers encircled an isolated Foreign Settlement whose numbers included a future American president, the young mining engineer Herbert Hoover. So widespread was Western dismay over a possible massacre that the leaders of eight otherwise contentious nations suspended their disputes and agreed to organize a global rescue force. It eventually grew to an army forty thousand strong recruited from the British Empire, the newly assertive United States, Tsarist Russia, Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany, Republican France, Hapsburg Austro-Hungary, Savoyard Italy, and Imperial Japan.

On August 14, the relief force charged into the capital, where its troops rapidly dispersed the now-frantic Boxers. On its fifty-fifth day, the siege ended. The Dowager Empress and her courtiers fled. A punitive peace followed, with the victors imposing a huge indemnity on China, four times its gross income as of 1900. The now-humbled Celestial Empire dwindled into vassalage as it deferred to the demands of its foreign masters. Moreover, allied forces occupied the Forbidden City for a year after the Dowager Empress fled; during those months there was continual looting of stored artworks.

In 1908, Dowager Empress Cixi, China’s de facto ruler since 1861, finally expired. She began her rise as a handsome Manchu concubine of the fourth rank who, on an auspicious night, was chosen to sleep with Xianfeng, the seventh Qing dynasty ruler. She bore him his only son who succeeded at age six, enabling his mother to reign as co-regent. When Emperor Tongzhi died at nineteen, Cixi contrived to become the adoptive mother and regent for her nephew, the Guangxu Emperor, and by virtue of her will and wit, she continued to dominate. Cixi survived rebellions, military debacles, and famines; she frustrated efforts at reform and lived profligately, resplendent in her dragon robes, or in her cape composed of 3,500 perfect pearls.

And yet, Cixi personified what her empire had lost: its proud sense of worth and sovereign dominion. The twelfth and last Manchu emperor, Puyi was forced to abdicate on February 12, 1912; he would later became Japan’s figurehead ruler in Manchuria, and finally a gardener in Chairman Mao’s People’s Republic.

To triumphant Westerners, the Boxer Rebellion seemed a defining battle between the children of darkness and light, in which the latter’s victory hastened the deserved dissolution of a senescent Middle Kingdom. Over time, this self-flattering scenario has also dissolved. Within post-1949 China, the fanatic Boxers were reborn as early-day anti-imperialist rebels, if sometimes misguided. For their part, European and American revisionists stress that the conflict between Chinese Christians and Boxers was mutually combative. Casualties were considerable on both sides in a civil conflict that claimed as many as 120,000 lives. As the British-based historian Odd Arne Westad notes in China and the World (2012), “When in 2000 the Vatican canonized 116 Catholics who were killed by the Boxers, the Chinese Foreign Ministry referred to the same people as ‘evil-doing sinners who raped, looted and worked as agents of Western imperialism.’” In America, Oberlin College amended its 1902 memorial to its graduate missionaries who perished as “massacred martyrs” at the hands of the Boxers. After an intensive faculty-student debate at Ohio’s well-regarded liberal arts college, a new plaque was added in 1995, dedicated to the memory of Chinese martyrs who also perished in the century-old Boxer Rebellion.

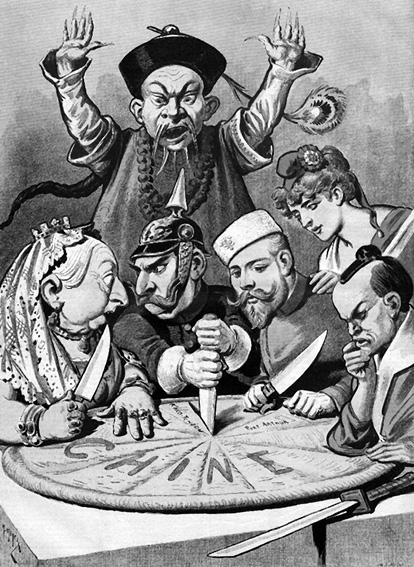

“China: The Cake of Kings,” as viewed by French political cartoonist H. Meyer in 1898, the year the slicing peaked.

Overall, what is now a revisionist judgment was put forward decades ago by Harvard’s Walter Langer in The Diplomacy of Imperialism (first published in 1935, updated in 1951). “European diplomats as a whole had no ground for priding themselves on the handling of the Boxer movement and its aftermath,” wrote Langer, then preeminent in his field.

Europe’s treatment of China in the whole period from 1895 to 1900 had been devoid of all consideration and of all understanding. The Celestial Empire to them was simply a great market to be exploited to the full, a rich territory to be carved up like a sirloin steak. Hardly anywhere in the diplomatic correspondence does one find any appreciation for the feelings of the Oriental or any sympathy for crude efforts made at reform. The dominant note was always that force is the father of peace and that the only method of dealing successfully with China is the method of the mailed fist.

Langer’s judgment is sustained by the views privately expressed by Sarah Pike Conger, wife of Edwin Conger, the just-cited American minister. “As I am here and watch, I do not wonder the Chinese hate the foreigner,” she wrote to her nephew from Peking in 1899. “The foreigner is frequently severe and exacting in this Empire which is not his own. He often treats the Chinese as though they were dogs and had no rights whatever—no wonder that they growl and sometimes bite.” Among the patronizing Americans that Mrs. Conger frequently encountered, it happens, was her husband’s deputy, First Secretary Herbert Squiers, a square-jawed former army cavalry officer who during the Legation siege became chief of staff to Sir Claude MacDonald, the commander in chief. Both agreed on the need to teach a lasting lesson to the Chinese, which helps explain the first secretary’s takeaway role in the looting that shortly followed the arrival of the multinational relief force.

As the Boxers scattered, and as the guns fell silent in Peking, the liberators celebrated with boisterous parades, the blare of military bands, and the hoisting of flags, while terrified shopkeepers posted such signs as “Noble and good Sir, please do not shoot us!” On August 28, soldiers from the eight armies joined with the diplomatic corps in a triumphal march through the Gate of Heavenly Peace into the no-longer-sacrosanct Forbidden City. Anthems and speeches over, the liberators swept through its royal quarters, ignored the angry stares of court eunuchs, posed for photographs on once-inviolable thrones, and began grabbing what they could.

While the looting spread, “a horrific bloodbath was conducted against the Chinese out of all proportion to their presumed guilt,” writes Sterling Seagrave in Dragon Lady (1992), his revisionist biography of the Dowager Empress. Victors’ justice was instant and brutal. Grisly images of ordinary civilians gawking at severed heads are preserved on film. Most foreigners—diplomats, soldiers, clergymen—then joined in what Australia’s Sydney Morning Herald called “a carnival of loot.” That so many nonmilitary personnel participated in this carnival; that its carnage was instantly recorded by journalists; that it persisted for weeks rather than days; and that it occurred throughout Peking, not just in a confined outlying area—all this contrasted with the sack of the Yuanmingyuan four decades earlier.

Something else had changed: the laws of war. In a landmark event often overlooked, it was none other than Abraham Lincoln who put into effect the first comprehensive, clearly defined, and civilized code of warfare. On April 24, 1863, President Lincoln signed General Order 100, which set forth in unequivocal terms the written rules regarding treatment of war prisoners, enemy-owned property, and “battlefield booty.” Articles 35 and 36 expressly protected “classical works of art, libraries, scientific collections,” with ultimate ownership rights to be settled in peace negotiations.

Hence President McKinley (himself a Civil War veteran) vainly ordered U.S. forces in Peking to desist from looting. No less disapproving was Germany’s Field Marshal Count von Waldersee, the supreme commander of the multinational army, who subsequently wrote: “Every nationality accords the palm to some other in respect to the art of plundering, but it remains the fact that each and all went in hot and strong for plunder.” This vandalism was no doubt deplorable, writes Peter Fleming, a chronicler of imperial wars in his 1959 account, The Siege at Peking, “[b]ut a spirit of revenge was abroad, the city was in disorder, and half-abandoned, and it may be questioned whether it was humanly possible to prevent looting in the first place, still less to stop it once it had started. It went on squalidly for months.”

Still and tellingly, in major art auctions that followed, works pillaged in Peking were not identified as such. By contrast, in the case of trophies harvested by Anglo-French forces in 1860, the candid description “From the Summer Palace” helped ensure higher bids. Not so after 1900. Hardly had the pillage ceased than the provenance of its prizes was cloaked in denial. Norms had changed. This became evident in the case of Herbert G. Squiers, the American Legation’s first secretary, who on departing from Peking in September 1901 also took with him “a collection of Chinese art filling several railway cars, which experts pronounce one of the most complete in existence.” It consisted largely of porcelains, bronzes, and carvings, “bought from missionaries and at auctions of military loot.”

So reported The New York Times from Peking in 1901, adding that Squiers intended to present his collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By all accounts, the fashionably groomed and ingratiatingly ambitious diplomat began collecting porcelains during his prior posting in Japan. Once stationed in Peking, Squiers assiduously cultivated dealers and became a knowledgeable buyer, aided by the linguistic skills of a Legation associate and the networking skills of his socialite wife, Harriet Bard Woodcock. But did he engage in looting? So press accounts asserted; it was even said that some of his choicer items were purchased from Bishop Favier, the Catholic vicar of the congregation to which Squiers belonged (the bishop denied wrongdoing, but acknowledged he did sell some things to help feed his starving flock). Eyewitnesses noticed that the first secretary was among the first to forage in the royal chambers of the Forbidden City.

U.S. Minister Edwin Conger (far left) confers with his Peking staff, headed by Herbert Squiers (far right) and William Rockhill (back right), ca. 1901.

In a further token of changing mores, a reporter for The New York Times asked a leading curator at the city’s preeminent museum about the propriety of accepting “looted art.” George H. Story tartly responded, “The Metropolitan Museum of Art does not accept loot.” He then elaborated: “I think it is an outrage that such a suggestion should be made in connection with anything which Mr. Squiers has to give. He is a gentleman, and has one of the finest porcelain collections in the country, I am told. It would be presumed by the Museum that Mr. Squires’ collection had been honestly got, he being a gentleman without question. I see no reason in the world why the collection spoken of should not be accepted.”

As of 1901, as was now apparent, looting had become bad form; at least a pretense of virtue was expected of donors. Hence a century later, the Chinese People’s Republic seized on this shift in formally avowed ethics to challenge Western collectors, dealers, and auction galleries. Over time, Mao’s heirs learned to employ the tools of capitalism to redress the excesses of Western empire building and win nationalist applause even from non-Marxists. Hypothetically, Beijing’s avenging agents may have even ventured into the dark side of outright theft.

As related earlier, China’s aggressive recovery campaign commenced in Hong Kong when Beijing in 2000 formally urged the withdrawal from a scheduled sale by Christie’s and Sotheby’s of three bronze animal heads. A second round followed in 2003. The prize was a bronze boar or pig (designations differ), which was purchased privately for $1.3 million by the China Cultural Recovery Fund, using money contributed by the Macao-based entrepreneur and casino mogul Stanley Ho. The fountainhead was presented with suitable fanfare to the Poly Art Museum, and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage acclaimed Ho for his “patriotic act.” Then came a third round. In January 2005, China’s National Philatelic Corporation prepares the way by issuing a set of stamps depicting all twelve zodiac creatures, featuring the four already recovered together plus artistic renderings of the eight still missing. In October 2007, Sotheby’s Hong Kong announces a provocative theme sale, “Lost Treasures from the Qing Palaces,” featuring a horse from the zodiac ensemble. “This is stolen property,” protests Xu Yongxiang, a buyer for the state-run Shanghai Museum. “It should be returned to the Chinese people through the government, not sold.” Although the bronze fountainhead is expected to fetch more than $7.7 million, Sotheby’s this time brokers a private sale between the consigner and Stanley Ho, who reportedly pays $8.9 million. Once again, the Macao gambling magnate is hailed as a national hero and the horse is added to the Poly Art Museum’s expanding menagerie.

All of which leads to a resonant finale centering on yet two more missing heads: a rabbit and a rat. It is February 2009 in Paris. The subject du jour in the art market is Christie’s forthcoming sale of the Yves St. Laurent Collection, as selected by the late couturier’s partner, Pierre Bergé. Among the works showcased at the Grande Palais are a needle-nosed rat and wide-eyed rabbit, although Christie’s in its advance publicity seeks to play down their presence by emphasizing other Asian art in a sale whose offerings range from Impressionist paintings to Ottoman ceramics.

To no avail: the two animals dominate headlines when China angrily protests the presence of the bronzes. Beijing’s Foreign Ministry charges that the sale violates international conventions and that it abuses both the cultural rights and sentiments of the Chinese people. Eighty-five Chinese lawyers bring suit in Paris to block the sale. Yang Yongju, publisher of The European Times, the flagship Chinese-language newspaper in France, speaks for the diaspora: “It is unacceptable to put stolen works up for auction.” Student demonstrators wave a forest of placards. “We want the French people to understand that we are rational and our requests are legitimate,” says Zhou Chao, a Chinese student at a French polytechnic institute, as he passes out protest pamphlets.

Unfazed, Christie’s executives press ahead with the sale they insist is wholly within the law. When the bronzes are on the block, bidding is vigorous and both rabbit and rat are claimed by an unnamed contender who by telephone offers the equivalent in euros of $36 million for the pair. The winning bidder then reveals himself as Cai Mingchao, a collector and an agent of the National Treasures Fund—who then announces that he will not pay, since the two heads rightfully belong to China and are therefore stolen goods.

In the cacophony that followed, Western critics recalled that the zodiac fountain actually did not work well and in any case was of European design and in no ways authentically Chinese. For his part, Pierre Bergé injected human rights and offered to return the bronzes free of charge if China changed its repressive Tibetan policies. The denouement was reached in April 2013, propitiously timed for a visit to China by French president François Hollande, when French billionaire François-Henri Pinault, scion of the family whose company apparently owned the animals, promised to give them back. (The Pinaults are the owners of Artemis, which controls a number of luxury brands, including Gucci, Bottega Veneta, and most importantly St. Laurent as well as Christie’s. Artemis does nearly 10 percent of its business with mainland China.)

Given the abundance (estimated by the Chinese as 1.6 million) of imperial items, where might such claims end? A good question, still lacking a credible, logical, and just response. Absent a consensus, confusion persists. So does anger and the likelihood of possible tit-for-tat looting.

Item: In August 2010, a gang of thieves broke into three display cases at the Chinese Pavilion on the grounds of the royal family’s residence at Drottningholm Palace in Stockholm. In just a few minutes they made off with a quantity of “old, beautiful Chinese objects.” A Swedish antique expert stated that there was a risk that they would be transported to China, as the value of Chinese art had risen rapidly in the last few years.

Item: In January 2012, the British auction house of Woolley and Wallis put up for sale a gold box embellished with seed pearls, enamel, and glass panels with floral motifs. Its lid bears this elegant lettered inscription: “Loot from Summer Palace, Pekin October 1860 [signed] Captain James Gunter, King’s Dragoon Guards.” This increased its potential value by 50 percent, according to the auction house’s spokesperson, who added: “Captain Gunter probably took the box from the Summer Palace as he viewed it as the spoils of war rather than act of theft—as a souvenir or reward of a great achievement.” This prompted a flurry of protest in China, but the engraving indeed boosted bids. The box fetched the equivalent of $764,694, as sold to an anonymous Chinese bidder, who once again refused to pay.

Item: In April 2012, thieves broke into the Malcolm MacDonald Gallery in Durham University’s Oriental Museum and snatched a large jade bowl and a porcelain sculpture, from China’s Qing dynasty, with a combined value of two million pounds. The bowl, dating from 1769, was from the collection of Sir Charles Hardinge, which in turn came to Durham along with prize objects gathered by MacDonald (1901–81), son of the Labor Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald and himself a diplomatic troubleshooter in Asia and Africa. Police later arrested two men suspected of being involved in the theft. Subsequently, both artifacts were recovered by the police.

Item: In May 2012, British police arrested two men believed to have taken part in the theft of eighteen rare and mostly jade Chinese artifacts in the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge University.

Item: In September 2013, seventeen men and two women were arrested in countrywide dawn raids conducted by hundreds of British police. They were charged with conspiring to burgle the Fitzwilliam Museum artifacts, most of which were recovered. This followed a pan-European investigation into museum thefts of rare works believed to have been “stolen to order” for Chinese collectors.

Item: In January 2013, in what Norwegian police described as a daring theft, twenty-three Chinese artworks and artifacts were stolen from the Chinese Collection of the Kode Museums in Bergen. They were from the trophies gathered by Johan Wilhelm Nortmann Munthe (1864–1935), a soldier and explorer who took part in the multinational rescue army that ended the 1900 Boxer Rebellion. This was the second time in three years that such a goal-oriented raid occurred; in 2010, thieves made off with fifty-six items. Erland Hoyersten, the director of the Bergen art museums, believes the thieves had “a shopping list” since “it’s entirely clear that they knew what they were after.”

Is there a message in these episodes? Can it be that objects are stolen to order? Is Beijing implicated in what could be called cultural hacking? Given China’s economic and diplomatic importance, what sensible steps can be taken to resolve a historic dispute of benefit only to demagogic nationalists? A good way to start, surely, would be for Americans to come clean on how and why we have collected China—the theme of this book.