Four stages can be distinguished in the odd coupling of the United States and China, the youngest and the oldest of great powers: discovery, expansion, fascination, and revision. On both sides, human impulses proved crucial. Yet a basic, impersonal, and often forgotten commercial reality precipitated America’s initial swerve to the Asian Pacific. In the 1780s, although our own newly independent republic was officially neutral, its trading vessels were trapped in the cross fire of the Franco-British wars. Yankee sea captains were continuously harassed by the Royal Navy, which seized hundreds of ships, confiscated their cargoes, and subjected their crews to forced recruitment. Hence American shipowners anxiously searched for markets elsewhere, preferably as far as possible from the quarreling and bothersome Europeans. As Phineas Bond, the British consul in Philadelphia, reported in 1787, “In the restricted state of American trade it is natural for men of enterprise to engage in such speculation as are open to them, and which afford a prospect of profit.”

Hopes for relief soared on two auspicious days. On May 11, 1785, the Empress of China returned from the Far East to New York Harbor, her hold stuffed with tea, becoming the first American mercantile vessel to reach the city of Guangzhou (then known as Canton) and its hongs, or trading companies. Commenting in Philadelphia, then the capital, the Pennsylvania Packet noted on May 16, “As the ship has returned with a full cargo, it presages a future happy period of our being able to dispense with that burdensome and unnecessary traffic which hitherto we have carried on with Europe—to the great prejudice of our rising empire, and future happy prospects of solid greatness.” The trip required fourteen months and twenty-four days, and logged 32,548 miles.

As propitious were the festivities in Salem, Massachusetts, on May 22, 1787, when the sails of the Grand Turk loomed on the horizon. She was the first ship from New England to trade directly with China. Leading the cheers was her financier, Elias Hasket Derby, who quickly found a promising market for his ship’s cargo of tea, porcelain, silks, jewelry, artworks, and dishware. He was in every sense an adventurous entrepreneur; along with others of his vessels, the Grand Turk was formerly a privateer, armed with twenty-eight guns and skilled at evading the Royal Navy during the American Revolution.

Soon fleets of Yankee ships began commuting regularly to Canton, laden with Spanish bullion (gold and silver coinage), fur pelts, wheat, and ginseng (an aromatic herb grown in the Appalachians and prized in China). In time, opium acquired in India was added to the list. By the 1840s, the import and export tonnage of U.S. vessels in Canton exceeded that of the British East India Company. Young America’s Pacific presence was further enhanced in 1791 when the first Yankee whaler rounded Cape Horn in search of sperm whales in Pacific waters. By 1830, the United States was the world’s preeminent whaling nation. Altogether, it was a seafaring era replete with dramatic encounters, its flavor captured in Patrick O’Brien’s excellent Aubrey and Maturin novels.

For owners and skippers, the hazards of the Pacific trade were amply rewarded. Remarkably, Salem in 1800 had become, per capita, America’s wealthiest city, generously realizing the city’s motto: “To the Farthest Ports of the Rich East.” Elias Hasket Derby, the godfather of the China trade, was reputedly America’s first millionaire, his affluence noted by his fellow Salem citizen (and Customs House clerk) Nathaniel Hawthorne. (More surprising, in a recent estimate of the seventy-five richest persons in recorded human history, Derby ranked seventy-second, his wealth in current dollars estimated at $31.4 billion.)

Derby’s legacy was cultural as well as monetary. He was among the first Americans to prize the porcelain treasures of China. While in Canton, the captain of the Grand Turk commissioned a monogrammed 171-piece dinner set, a 101-piece tea service, plus a large punch bowl depicting Derby’s vessel and inscribed “Ship Grand Turk” and “At Canton 1786.” The bowl was originally presented to the Grand Turk’s officers and eventually donated by Derby’s son to Salem’s Essex Institute, founded in 1799, home of the first comprehensive archive of documents and memorabilia relating to America’s formative links with East Asia. The institute evolved into today’s Peabody Essex Museum, whose collection of 1.3 million objects presently includes the actual residence of a wealthy Qing dynasty merchant, lawfully transplanted, piece by piece, from the People’s Republic of China. Indeed, it is reasonable to assert that the current administration’s multifaceted pivot to the Asian Pacific had its origins in the docks, the shops, and the now-ghostly former Customs House of Salem.

This bowl was presented to the officers of the Grand Turk, the third U.S. vessel to reach China. Donated to the Peabody Essex museum by the son of its owner, Elias Hasket Derby.

Boston succeeded Salem as America’s premier trading port, its harbors better equipped to handle the clipper ships sailing to the Orient with their occasional cargoes of Indian opium. (A little-publicized reality is that many New England fortunes, including those of the Forbes, Russell, Sturgis, and Delano families, had roots in the opium trade. Instead, contemporary American publications commonly appended the adjective “British” when referring to the opium trade.) In May 1843, the U.S. government learned of the successful negotiation—some would say extortion—of the Treaty of Nanking by the British, which ended the First Opium War; one of the provisions granted by the Middle Kingdom opened (in addition to Canton) four more ports to trade by English merchants: Ningpo, Amoy, Fuchow, and Shanghai.

On February 27, 1845, after 211 days at sea, a fleet of four ships cast anchor at Macao. On board the frigate Brandywine was Newburyport, Massachusetts’s own Caleb Cushing, lawyer and congressman, now “Commissioner to China and Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States to the Court of that Empire.” “Count” Cushing’s (President John Tyler thought this title added to the prestige of the event) orders were to secure the entry to all five treaty ports “on terms as favorable as those which are enjoyed by English merchants.”

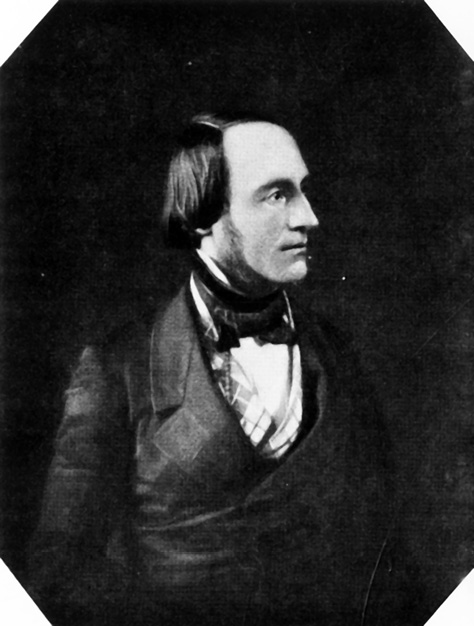

Whig politician Caleb Cushing (Harvard, 1817) never did meet the Son of Heaven, but he secured America’s first treaty with China.

Born in Salisbury, Massachusetts, the precocious Cushing graduated Harvard at the age of seventeen and settled down to practice law in Newburyport in 1824. A diehard Whig, he was elected first to the state legislature and then to the U.S. Congress, before being dispatched to China. Prior to his departure, anticipating a meeting with the Celestial Emperor, the dashing Cushing outfitted himself in an imposing “Major-General’s blue frock-coat with gilt buttons and some slight additions in the way of embroideries, gold striped trousers, spurs and a hat with a white plume.” However, the imperial encounter between the “Count” and the Son of Heaven never took place. Cushing’s request to proceed to Peking was declined; President Tyler’s letter of “peace and friendship,” conveying his very best wishes for the emperor’s long life, was never delivered. Instead the Celestial Emperor dispatched Viceroy Keying (Qiying), who had dealt with the British, to treat with Cushing. The ensuing agreement, known officially as “The Treaty of Peace, Amity, and Commerce, Between the United States of America and the Chinese Empire,” was signed on July 3, 1844, in a temple in the town of Wanghia (Wangxia), just outside Macao. It granted Americans free access to the five ports accorded to the British, and a vital new prerogative: extraterritoriality. This meant that American citizens in China were subject only to the laws of the United States. On this provision, Cushing commented, “it was unwise to allow any control over the lives and property of American citizens in governments outside the limits of Christendom.” Although the trade was now declared illegal, “a certain amount of opium smuggling continued.”

Boston’s merchants were free to trade in tea, china, and cotton fabric, the latter soon to be loomed in quantity in Francis Cabot Lowell’s Massachusetts mills. Fast clipper ships plied the routes between China’s hongs and New York and London’s wharves. Writing in 1921, Harvard’s Samuel Eliot Morison, the great chronicler of America’s maritime history, offered a rueful epitaph to the overall decline of New England’s commercial ties to East Asia: “To-day no trace remains in Boston of the old China trade, the foundation of her commercial renaissance, save a taste for li-chi nuts, Malacca joints, and smoky Souchong.”

As Boston’s commercial ties to the Far East diminished, the city featured a fitting memorial in the form of an important and innovative event, the first of its kind in New England. Cushing’s landmark agreement was celebrated with the “Great Chinese Museum” (1845–47), an elaborate and path-breaking exhibition at the Marlboro Chapel on Washington Street. It followed close on the heels of a parallel venture in Philadelphia, a private museum featuring “ten thousand Chinese things,” including artifacts, life-size mannequins, paintings, and re-creations of Chinese shops. The collection was assembled by Nathan Dunn, a Quaker merchant who had traveled to China, where he was based in Canton for eight years. Opening in 1838, the professed aim of the Philadelphia museum was to educate the public about Chinese culture. As Dunn was not involved in the opium trade, he had been received favorably by the Chinese, who helped him collect through agents in areas otherwise off-limits to foreigners; hence he could claim unparalleled access to works of art inaccessible to other Westerners. Before it closed in 1842, an estimated 100,000 people visited Dunn’s Chinese Museum, buying 50,000 copies of the first catalog of its kind. The museum then relocated to London, where its breadth earned a favorable report from the young Queen Victoria. After Dunn’s death in 1844, his curator toured England with the collection, which then was dispersed at auction and in private sales—one buyer being P. T. Barnum.

By contrast, the wider purpose of Boston’s “Great Chinese Museum” was to exhibit “at a glance the Appearance, Agriculture, Arts, Trades, Manners and Customs of the Chinese, the oldest and most populous nation on the Globe.” A critical reviewer dubbed the museum “the Crockery-dom,” intended to appeal to visitors whose ideas of China were formed from dinnerware encounters on export porcelain.

One of the treaty mission members, the New York engineer John R. Peters Jr., provided the objects he had collected and appears to have authored the museum’s catalogue. According to John Rogers Haddad, in his account of America’s early encounters with China, Peters had in fact joined the Cushing delegation in the hope that under the auspices of the government he would be able to exhibit and explain to the Chinese “models and specimens of American arts and production,” including time- and labor-saving devices produced by Yankee inventors. Reciprocally, Peters hoped to obtain objects and information from “the ancient nation for the benefit of our country,” thus scoring a first in the cultural exchanges between China and the United States.

Americans assumed that the Chinese attributed their defeat in the Opium Wars to the superior technology of foreign weaponry and that a display of American models—a steamship, locomotive, telegraph, and gasworks—built by the mechanically gifted and enterprising John Peters would open doors to trade. As Cushing explained to Viceroy Keying:

Your excellency is doubtless aware that all the modern improvements in the arts of war & navigation are adopted and practiced in my country quite as thoroughly and extensively as in Europe. That if your government is desirous of books on . . . engineering, ship-building, steam engines, discipline of troops, or manufacture of arms, or any other subject whatever, I shall be happy to be the means of placing them in your hands. I also tender to you models for the construction of the instruments of war as now used in Europe and America. Also the services of engineers skilled in these arts, to construct for your government ships, steamers, cannon, & arms of all sorts, either in China or in America as may be preferred.

Cushing’s papers are silent as to whether Peters ever presented his models to the viceroy, but having returned to America, he was able to carry out the second part of the plan when “The Great Chinese Museum” opened its doors in Boston. Designed to display the high level of Chinese civilization, the exhibition was intended as well to persuade local entrepreneurs that the Middle Kingdom’s mandarins could be ideal trading partners for Boston’s Brahmins.

Guests gasped at the glowing lanterns hanging from the ceiling, and at a hovering giant dragon, along with numerous paintings and scrolls. Besides Peters’s chinoiseries, there were dioramas with costumed mannequins; Case One pointedly portrayed the emperor robed in imperial yellow seated on a dragon chair as he signed the Wanghia Treaty. Less felicitously, Case Five featured a wealthy man at home smoking opium. (The catalogue entry discussed the history of opium use in China and righteously claimed it was the British who had encouraged the baleful trade, in defiance of the emperor’s prohibition.) Smaller cases displayed obligatory porcelains, enamels, embroideries, miscellaneous models, and utilitarian items. Highlights in the gallery included a huge seven-foot panorama of Canton, featuring portraits of prominent local merchants and Viceroy Keying. Present in the galleries were two live Cantonese, dressed in “native costume.” The English-speaking T’sow-Chaong, a self-described “writing master,” answered visitors’ questions. Le-Kaw-hing, a former opium-addicted musician, sang and performed on various instruments, adding verisimilitude to the occasion. As a local reporter enthused, “Who would not like to visit China, walk through the streets of its cities, penetrate the mansions of its inhabitants, partake of savory bird’s nest soup . . . or quaff real souchong, from real China ware, in the company with real Chinese? There are none who, if circumstances permitted, would not desire to see the many curious things which distinguish that curious people. To us, whose business, time or means, forbid so long a voyage, there is now offered a most desirable opportunity.”

The museum’s entrance was adorned with a carved lacquer and gilt cornice, flanked by two dragon-painted lanterns and tablets with Chinese characters, which, when translated in the catalogue, read: “Words may deceive, but the eye cannot play the rogue.” Among the visitors was fifteen-year-old Emily Dickinson, then staying with relatives in Boston. Emily obtained two cards for herself and her sister Lavinia, each inscribed in calligraphy by the writing master, which (as she wrote to a friend) she held “very precious.” The music sung and played by Le-Kaw-hing “needed great command” over Dickinson’s “risible faculty” to keep her sober, “yet he was so very polite” that she was “highly edified with his performance.” But ultimately it was the “self denial” that had allowed him to overcome his opium addiction that she found “peculiarly interesting.” The Japanese-American scholar Hiroko Uno has speculated that Dickinson’s lifelong pattern of withdrawal, self-denial, and renunciation might have been prompted by her being drawn to Case Four, in which Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism were expounded. As explained in the guidebook, a central doctrine of Buddhism is “that all things originated in nothing, and will revert to nothing again. Hence annihilation is the summit of all bliss; and nirupan, nirvana, or nonentity, the grand and ultimate anticipation of all.”

As Uno elaborates, any number of Emily Dickinson’s poems resonate with the poet’s mystical/ironical/paradoxical/universal sense of the Divine, sometimes mingled with her reflections on the material culture of the Celestial Empire, as in these lines:

His Mind like Fabrics of the East—

Displayed to the despair

Of everyone but here and there

An humble Purchaser—

For though his price was not of Gold—

More arduous there is—

That one should comprehend the worth,

Was all the price there was—

The quotations could be multiplied, suggesting that New England’s premier mystical poet, living in Amherst, confiding her verse to a dresser drawer, plainly anticipated the nonmaterial allure that would draw a future generation to the aesthetics and theology of the Far East.