In examining America’s cultural relations with China, one question persistently occurs: Why has Harvard University played so outsize a role in promoting the potent allure of the Far East? Some reasons are self-evident. The country’s oldest university (b. 1636) came of age when maritime New England was the propellant of commerce with the Pacific East. In the words of Samuel Eliot Morison (Class of 1912), the years 1783–1860 formed “that magic era when America first became a world power, and Salem boys were more at home in Canton than in New York.” The seaports of Massachusetts generated not just the undergraduates but also the mercantile fortunes that gave Harvard a running start in its race for primacy. Harvard saw itself in the role of educating these custodians of culture. As Mark Twain remarked: “In Boston they ask, how much does he know? In New York, how much is he worth? In Philadelphia, who were his parents?”

Yet there were other, less obvious reasons for Harvard’s—and Boston’s—gravitation to the Sino-Japanese world. During the spiritual anarchy of the post–Civil War, post-Darwin decades, the New England illuminati, beginning with Emerson, looked eastward in search of transcendental truths. Just as China’s interest in Buddhism was waning, it exerted a magnetic pull on Boston’s ruling caste. Thus when Henry Adams, shaken by his wife Clover’s suicide, began his restless global travels with the artist John LaFarge in 1886, their initial goal was Japan in quest of Nirvana (so LaFarge informed a baffled young reporter as they stopped in Omaha, who shot back, “It’s out of season!”). In fact, Adams (Class of 1858) and LaFarge were part, as we shall see, of a crowded brigade whose members sought to counter the vulgarities of the Gilded Age with the wisdom of the East.

A third likely reason for Harvard’s liaison with the Far East is implicit in Boston’s self-regarding metrocentric vernacular. From the 1850s onward, two new terms were affixed to the city and its blood-proud, Harvard-trained elite: Bostonians viewed their city as the metaphorical hub of the world, under the guidance of its own hereditary Brahmin caste, the closest approximation to an American aristocracy. Both “Hub” and “Brahmin” were coinages introduced by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (Class of 1829), the witty autocrat of the breakfast table and author of the poem “Old Ironsides,” not his son, the eminent jurist. As Holmes explained, he considered Boston “the thinking center of the continent, and therefore of the planet.” He was careful to add that the Hindu concept of a divinely anointed caste possessed a corollary: Brahmins were expected to nourish and maintain not only temples of their faith, but cultural institutions as well. Moreover, when sons of Harvard turned searchingly to China, note was taken of the high value its mandarins accorded to excellence in the arts and literature.

The founders of the Boston Athenaeum (b. 1807), a private library that added an art gallery in 1827 for a series of yearly exhibitions of American and European painting and sculpture, reminded their fellow benefactors that as “we are not called upon for large contributions to national purpose,” the savings could be used “by taxing ourselves for those institutions, which will be attended with lasting and extensive benefits” for Boston. Between 1870 and 1900, the Brahmins contributed beneficially to Harvard and to the patronage that seeded the Athenaeum, and then the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (b. 1870), the Boston Symphony Orchestra (b. 1881), plus a pride of clubs, schools, hospitals, and the final resting place for Bostonians: the impeccably landscaped Mount Auburn Cemetery (b. 1831). (A long-standing definition of a Boston Brahmin is someone with a share in the Athenaeum, a relative in McLean’s [psychiatric hospital], and a plot in Mount Auburn.) During the nineteenth century, Boston also cradled outstanding journals (The Atlantic and The North American Review), publishing houses (Little, Brown and Houghton-Mifflin), and a very Bostonian religion: the heterodox but liberal Unitarians, the denomination associated with Harvard’s Divinity School. Unitarian tradition was said to proclaim “the Fatherhood of God, the Brotherhood of Man, and the Neighborhood of Boston” (so writes Helen Howe, a disciple by heredity).

The “longing for the East was a symptom of the moment, especially marked in New England,” writes the literary historian Van Wyck Brooks (Class of 1908). “Numbers of Boston and Harvard men were going to Japan and China in a spirit that was new and full of meaning. Oriental art was the vogue among Bostonians, and they were filling their region with their great collections.” The pilgrim who led the way was Ernest Fenollosa, who in his time became America’s most eloquent prophet of “one world,” resulting from “the coming fusion of East and West.” Writing in the 1880s, he maintained that the vigor of Western civilization arose from knowledge of means, while the East’s strength lay in its knowledge of ends. “Means without ends are blind,” he wrote, while “ends without means are paralyzed.” This was a novel message during the Gilded Age. One can imagine the baffled expression among Harvard’s faculty and students on hearing Fenollosa’s Phi Beta Kappa poem, written from Japan, where he had just become a Buddhist monk:

I’ve flown from my West

Like a desolate bird from a broken nest

To learn the secret of joy and rest.

Fittingly, Ernest Fenollosa was born in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1853, the year in which Commodore Matthew Perry’s squadron set sail for the Bay of Tokyo. His father was a Spanish musician, born in Malaga, where he conducted the cathedral choir and taught the piano and violin. He therefore qualified to join a military band on a returning U.S. vessel. He liked and lingered in Salem, where he married a pupil, Mary Silsbee, the daughter of an East India shipowner, becoming an Episcopalian and a popular figure in the state’s musical scene. Thus young Ernest had the means, the background, and the education that propelled him to Harvard (Class of 1874), where he fraternized with the Brahmin elite and fell under the spell of Charles Eliot Norton, America’s foremost authority on the philosophy of art. Another pioneer in Asian studies was Edward S. Morse, a self-taught zoologist, originally on the staff of the Peabody Academy of Science in Salem, who pursued his researches in Japan and donated his collection of ceramics to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in exchange for a lifetime job as keeper of his pots. He gifted his collection of everyday objects to Salem’s Peabody Museum. When Morse was asked by the Japanese to recommend a teacher of philosophy, he turned to Norton, a trustee of the MFA, who suggested Fenollosa. Such was the networking route that took young Ernest to Japan, where he became entranced by the East, converted to Buddhism, and on his return to America became the curator of Oriental art at the MFA.

It is hard to overstate Fenollosa’s influence on his Harvard contemporaries (like Henry Adams), or on his friends in Japan (like Lafcadio Hearn), or on an early generation of modernist writers (like Ezra Pound). It suffices to say that before his death in 1908, this slim, ethereal, and eloquent advocate of the East had established Boston and by extension Harvard as the intellectual capital of East Asian art.

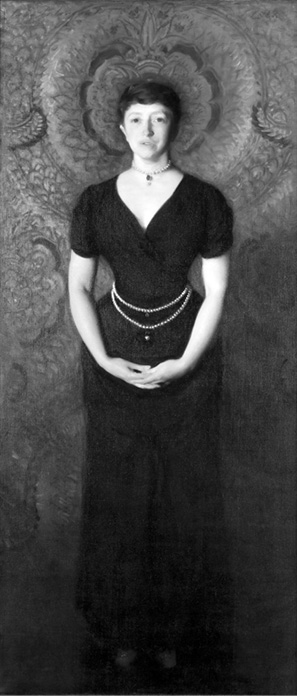

Isabella Stewart Gardner by John Singer Sargent.

Fenollosa’s protégé and successor as the MFA’s expert on Asian art was Kazuko Okakura, a transplant from Japan, who became the long-serving curator of the Chinese and Japanese department. Okakura also served as spiritual mentor, although not artistic advisor, perhaps fearing a conflict of interest, to Boston’s dowager empress of Fenway Court, Isabella Stewart Gardner, whose private museum opened to the public in 1903 with an orchestral fanfare by the Boston Symphony. Her new museum featured a succession of two “Chinese rooms.” The first housed Japanese screens and temple hangings, Chinese embroideries, plus a number of smaller objects. However, it was only after the opening of her museum that she met Okakura, newly arrived in Boston to advise the MFA. When Okakura died in Japan in 1913, Gardner hosted an incense-filled memorial service in the Music Room of her museum. One friend poured water over a stone on his grave on her behalf; another, Denman Ross, who occasionally acted as her unpaid agent, gave her Okakura’s lunch box and teacups, while Kojiro Tomita, his curatorial successor, collected plum blossoms from his grave. Gardner dedicated the second of her Chinese rooms, the “Buddha Room,” to Okakura’s memory. The Chinese theme was additionally apparent in the loggia of the museum, which housed a Chinese Eastern Wei votive stele bought through Bernard Berenson from the Russian art collector Victor Goloubew.

Gardner’s initial interest in the East had been prompted by hearing Morse deliver a series of lectures on Japan at Boston’s Lowell Institute in 1881. She invited him to repeat them for guests in her home. In 1883, along with her husband, Jack, a railroad financier, she decamped for Asia, visiting Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. Although they traveled with a sizeable entourage of luggage carts and porters, “Tartar” maids and personal cooks, wranglers, and dragomen, they followed the usual tourist itinerary—Shanghai, Tianjin, Peking, back to Shanghai, and then on to Hong Kong, Canton, and Macao. In Peking there were visits to the Observatory, Ming tombs, the Great Wall, and the ruins of the Yuanmingyuan. A site of special interest was the Yonghegong, the so-called Lama Temple of the Tibetan Buddhist Yellow Hat sect, where her diary records her observations on the architecture, the monks’ yellow robes, the chanting, and the art—carpets, cloisonné altar vessels, and the huge statue of Buddha. There were visits to missionaries and charitable organizations, and more unusually, because of Isabella’s keen interest in Asian religions, there were meetings with Buddhist and Daoist monks, sandwiched between doses of shopping, buying photographs, pressing gingko leaves in souvenir albums, and penning notations in her diary. Summing up their nineteen-day stay, she wrote: “Dust and filth and every kind of picturesque and interesting thing.”

Exotic travel suited the eccentric Isabella, and at home she was not above scandalizing Boston’s bourgeoisie. A favorite story had her hiring a locomotive to fetch her when she was late for a coaching party. Another had her appearing at balls with a page to carry her train. An avid baseball fan, she wore a pennant across her brow at a concert in Symphony Hall proclaiming, “Oh You Red Sox.” Her motto, inscribed above her bathtub, is revealing: “Think much, speak little, write nothing.” Although he could not claim to have known her personally, perhaps the best description of Isabella has been left by the former director of the National Gallery, John Walker (Class of 1930):

[S]he was an exhibitionist. She paraded around the zoo with a lion on a leash; she sat in the front row of prizefights; she drank beer instead of sherry at Pops concerts; she wore dresses from Worth so décolleté and tight-fitting that she was conspicuous everywhere. She had innumerable friends among men but very few among ladies.

Harvard’s Charles Eliot Norton (Class of 1846) served as her most important mentor. An author and the editor of the influential North American Review, he was the son of Andrews Norton, New England’s “Unitarian Pope,” and cousin to Charles William Eliot, Harvard’s president (by virtue of their both being grandsons of the merchant prince Samuel Eliot, according to contemporary legend the richest man ever to die in Boston). Reputedly the most cultivated and influential man in America, “Charley” Norton was a founding member of the Dante Society, whose early presidents were Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and James Russell Lowell (Class of 1838), and whose members included Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., William Dean Howells, and Isabella Stewart Gardner. Originally, their meetings, devoted to studying and revising the Italian translations of Dante by Longfellow, were held at the poet’s Cambridge abode, “Craigie House,” but were eventually moved to grander quarters at the Nortons’ ancestral home, “Shady Hill.” Set in a leafy park, it was there in Shady Hill’s golden brown study filled with paintings and medals, books and manuscripts that Henry James was introduced to Charles Dickens.

Mrs. “Jack,” as Isabella was familiarly called, was a frequent auditor of Norton’s lectures in which he preached the gospel of good taste—it was once remarked that when that professor entered Heaven, he would sneer, “Oh no! So overdone.” Norton launched her as a collector, sometimes acting as her agent. (When expenses at Shady Hill became onerous, he was not above selling her his rare books and manuscripts.) Besides Fenollosa and Gardner, Norton’s acolytes in the mid-1890s included three favored protégés: the philosopher George Santayana (Class of 1886), the art historian and collector Charles Loeser (Class of 1886), and the essayist and critic Logan Pearsall Smith, later to become the brother-in-law of another of Norton’s pupils (although less favored), the art historian Bernard Berenson. Santayana, Loeser, and Smith also appear to have been gay or bisexual, though discreetly closeted. Besides the Norton trio, other important bachelors who enjoyed tea times at Fenway Park included Henry James (attended Harvard Law School), the painter John Singer Sargent, and three future benefactors of the MFA: Ned Warren (Class of 1883), who gifted the museum with a collection of ancient Greek sculpture; Dr. William Sturgis Bigelow (Class of 1871, M.D. 1874); and Denman Ross (Class of 1875, Ph.D. 1880); the latter two major donors to the MFA’s Asian collection.

In the 1880s, New England’s mercantile fortunes, by then invested in real estate and railway bonds, subsidized a younger generation’s interests in the arts. Brahmins brought their business skills to running Boston’s cultural organizations, including the MFA, where they dominated the board of trustees. As cultural historian Neil Harris comments: “Eliots, Perkinses and Bigelows took their places; almost all of the twenty-three elected trustees were descended from old Yankee families and were men of wealth. All but one were Proprietors of the Athenaeum, eleven were members of the Saturday Club, five served (or would serve) on the Harvard Board of Overseers, half were members of the Somerset or St. Botolph Clubs and quite a number were blood relations.”

One such paragon was William Sturgis Bigelow. The beneficiary of a substantial China trade fortune, the third in a dynasty of doctors, Bigelow was the son of the Gardners’ family physician and a close friend of John LaFarge, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, and President Theodore Roosevelt. He was also the favorite cousin of Henry Adams’s wife, Clover, who, along with her husband, was an enthusiastic collector of Asian art. At his summer retreat on tiny Tuckernuck Island, off the western tip of Nantucket, described by Adams as “a scene of medieval splendor,” Bigelow banned women and encouraged skinny-dipping among the men, leading Senator Lodge to exclaim in anticipation of leaving sweltering midsummer Washington, D.C., for Tuckernuck, “Surf, sir! And sun, sir! And Nakedness! Oh Lord, how I want to get my clothes off.” Bigelow’s three-thousand-volume library provided houseguests with tomes on Buddhism, the occult, or (it was alleged) racier fare in three languages, for the hearties who lounged about nude or in pajamas—Bigelow preferred a kimono. But for dinner, formal dress was required.

Bigelow, who had heard Edward Morse lecture, invited him to Tuckernuck and accompanied him to Japan in 1882, where “the Doctor” was to spend seven years. He became a Buddhist, and on one occasion played host to the Gardners on their 1883 trip to the Far East. At one point in their friendship, Dr. Bigelow professed to find Mrs. Jack “a gloom dispeller, corpse-reviver, general chirker-up,” and in her honor christened his Chesapeake retriever Mrs. John L. Gardner, shortened to “Belle,” as he “could not really use the whole name and then whistle.” But he could also turn on her, echoing sentiments expressed by Berenson, who always referred to her as “The Serpent of the Charles.” Bigelow wrote Lodge in an outburst of unusual candor that she was “vain, meddlesome and impulsive,” with “not a very keen sense of the difference between loyalty and treachery. She would make friends with anybody or sacrifice any friend for caprice.”

On October 6, 1926, The Boston Evening Transcript front-paged two bold headlines: Babe Ruth had hit three home runs in a World Series game, but in larger type it reported that William Sturgis Bigelow had died. The MFA’s then curator of Chinese and Japanese art, John Ellerton Lodge, the son of Bigelow’s best friend, Henry Cabot Lodge, clothed him in a long gray kimono with his upper body dressed in the cloak of a Shingon Buddhist priest before cremating his remains. At his request, Bigelow’s ashes were divided between Mount Auburn Cemetery (founded by his grandfather, Jacob) and Japan’s Homyoin-Miidera Temple, where the priests buried him in the vicinity of Lake Biwa, near the remains of his friend Fenollosa. He bequeathed his collection of Asian art, numbering more than 26,000 objects, to the MFA.

Another among Boston’s bachelor aesthetes and museum patrons is the patrician figure of Denman Ross, who acquired art with the intent of leaving his collection to posterity. Professor, artist, collector, and author of influential treatises on design theory, Dr. Ross was, most importantly, trustee and benefactor of both the MFA and Harvard’s Fogg Museum. Over his lifetime, he gave eleven thousand works to the MFA and 1,500 to the Fogg. Although he collected in many areas, it is his focus on Chinese art that concerns us here.

The art historian Sir Kenneth Clark once wrote, “My collection is a diary of my life, the only one that I have ever kept.” The same might be said of Ross. His archived correspondence with museum administrators, curators, fellow collectors, and friends like Joseph Lindon Smith and Mrs. Gardner contains little of a personal nature. Instead it documents objects seen and collected, his trip itineraries, and admonitions as to how his gifts were to be displayed. But as the former MFA curator James Watt recalled in an interview, in studying his donation, he realized that “Ross was a great collector. I didn’t believe in ‘the eye’ until then, but he changed all that.”

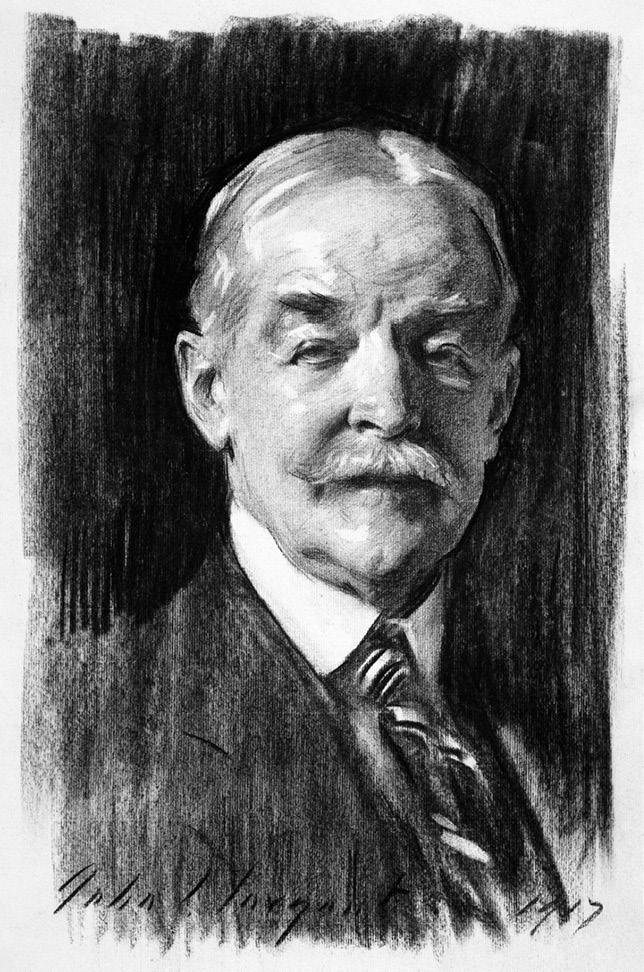

Denman Ross, a princely donor to the MFA (sketched by Sargent in 1917).

“My motive was the love of order and sense of beauty,” Ross explains in his notes for an autobiography. “The collecting of works of art is simply incidental. I had the money to spend, so I spent it.” When friends came to visit, “I found myself saying the same things about the same objects and telling the same stories over and over again, until I was ashamed of myself. I could not go on like that, so I gave my collections to the MFA, first as a loan and later as a gift.”

Ross donated a number of Chinese paintings to the museum, notably five rare paintings depicting Lohans (followers of the Buddha who have obtained enlightenment) dating from the early Southern Song dynasty, formerly in the collection of the Daitoku-ji Zen temple complex in Kyoto (see color plates, figure 14). Painted by Zhou Jichang and Lin Tinggui, probably between 1178 and 1188 CE, they were part of a set of one hundred scrolls brought to Japan in the thirteenth century. In 1894, Fenollosa arranged a loan exhibition of forty-four of the paintings. Among Boston’s cognoscenti, the exhibit caused a sensation. Ross took a visitor, his friend Bernard Berenson, to meet Fenollosa and view the collection before it was exhibited to the public. Noted for his connoisseurship of Italian painting, Berenson had a less well-known but strong interest in Buddhist art that, inspired by this exhibition, would grow into a great passion. He wrote to Mary Smith Costelloe, who was later to become his wife, that he was amazed to find “oriental art, now surpassing Dürer and now Gentile Bellini”:

They had composition of figures and groups as perfect and simple as the best we Europeans had ever done. . . . I was prostrate. Fenollosa shivered as he looked. I thought I should die, and even Denman Ross who looked dumpy Anglo-Saxon was jumping up and down. We had to poke and pinch each other’s necks and wept. No, decidedly I never had such an art experience. I do not wonder that Fenollosa has gone into esoteric Buddhism.

The temple was badly in need of repair and the paintings were serving as security for a large loan from a Japanese collector, and the monks appeared to have agreed to an American sale of ten paintings. At the end of the exhibit, Ross purchased five of the best paintings, which he eventually donated to the museum; the MFA also purchased five paintings. More mysteriously, two paintings that Fenollosa claimed to have misplaced and were never exhibited or offered to the MFA or Ross were sold by Fenollosa to Charles Freer. The curator seems to have believed he was owed a gift or commission by the temple. When the paintings were returned to Kyoto in 1908 they were deemed national treasures, and the sale has been regretted ever since.

Their purchase in 1895 marked the beginning of the MFA’s collection of early Chinese painting, for many years the finest in the West. Another famous painting donated by Denman Ross is The Thirteen Emperors scroll (see color plates, figure 13). Before it was exhibited in Tokyo, upon the occasion of the Japanese Emperor Hirohito’s enthronement in 1928, it was in the Fujian collection of the Lin family. Finally, Denman Ross acquired it in 1931 from the Japanese dealer Yamanaka.

More than seventeen feet long, executed in ink and color on silk, The Thirteen Emperors is probably the earliest Chinese hand scroll in any American collection. Although Ross and the MFA curator Kojiro Tomita purchased it as a Tang original by the court artist, Yan Liben (Yen Li-Pen), which is how it is listed on the MFA’s website, another scholar, Professor Qiang Ning, believes that it is a later, Northern Song (960–1126 CE) copy. Portrayed are the thirteen emperors who preceded the Tang ruler Taizong, accompanied by their officials. Ning theorizes that “the motivation behind the selection of these particular thirteen emperors . . . was to legitimize the sovereignty of Emperor Taizong,” who had seized the throne, murdering his older brother and forcing his father into retirement, and who was “therefore a likely candidate for patron of the portrait’s original version.” Each emperor is identified by an inscription. In the case of Wudi, the third in the line of Northern Zhou dynasty, who ruled from 561–78 CE, the scroll records that “he destroyed the Buddha’s Law.” (He acted under the influence of his minister, who was a Daoist.) Tomita asserted that “because of its extraordinary quality as portraiture, the scroll of the emperors is one of the chief masterpieces of the world.”

Tomita introduced Ross to the painting in a small reproduction. As the curator recalled, Ross said, “‘How can I get it?’ I told him it was in China. He said, ‘Try to get it.’ When it came to the question of price, it was many thousands of dollars [$60,000 Depression greenbacks]. He said, ‘I haven’t got that much money, but now I have to get it. I will call my lawyer.’ He did call and the lawyer said, ‘Dr. Ross, you are a bachelor and you have enough money, but you can’t spend all that amount at one time.’” Ross borrowed a substantial sum against collateral, and the museum advanced the rest. In his will, he left the MFA money to repay the loan with interest because, as Tomita recalled, “he was that type of man.”

Denman Waldo Ross was born in Cincinnati in 1853 to John Ludlow and Frances Walker Waldo Ross. Three other children died, so Denman reports, “I was left as the one and only child.” In 1862, the family moved to Boston near his mother’s Waldo relations, because, as Denman recalled, his father “did not like the idea of going into the army and leaving his wife and only child in Cincinnati with the enemy across the river.” His Waldo connections included grandfather Henry, who was a business partner of Amos Lawrence. Together they invested in the booming Lawrence mills north of Boston, perhaps inspiring Henry Waldo’s grandson’s lifelong interest in collecting textiles. His father, also an astute entrepreneur, together with his brother Matthias Denman (after whom Denman was named), acquired substantial holdings in the still-developing Back Bay real estate market, as well as interests in a number of other businesses, including power and roofing companies and a manufacturer of linen fishing lines, a particularly lucrative trade in Boston. Hence in those pre–income tax days, John Ross amassed a considerable fortune.

Once enrolled at Harvard in 1871, Denman studied history with Henry Adams, recently lured from the nation’s capital by Harvard President Charles Elliot. In his senior year, Ross enrolled in Charles Eliot Norton’s course “The History of the Fine Arts, and Their Relations to Literature.” Norton believed that history should follow practice, and thus although his course eschewed the pencil and paintbrush, it followed a course taught by Charles Moore on “Principles of Design in Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture.” Inspired by Norton, Ross also developed an interest in the work of England’s influential art critic John Ruskin and the pre-Raphaelite painters he championed and thus absorbed his mentor’s firmly held belief in the moral benefits of an art education. Ross became a leading proselytizer of the Arts and Crafts movement in America.

Study at Leipzig, a doctorate under Adams with a dissertation on German land reform published in 1883, followed, but the death of his father in 1884 freed Denman from the academic practice of history. The break was definitive: “My large collection of books in the field of Ancient Law was given to Harvard College. My study, where the books had been kept was turned into a studio, extended, enlarged and rearranged for the practice of painting and for my collection of works of art.” His inheritance, plus the rents derived from a large Back Bay apartment hotel, the Ludlow, built on family land across from Trinity Church, allowed him to embark on a lifetime of traveling, studying, and writing about art, painting, and collecting.

Dr. Ross pursued his new career devoted to teaching design theory at Harvard, first in its Architectural School and then, in 1909, in the Fine Arts department. Lecturing well into his seventies, he was remembered by a student as “massive, rubicund, somewhat dogmatic in his theories of design, and occasionally short of breath, but still eager to collect, to teach, and to enjoy beauty.”

He particularly liked lecturing at a summer school for artisans and schoolteachers, since he felt strongly that it was important to teach art to tradesmen and schoolchildren. Yet his teaching betrayed a strong authoritarian streak. What was once said of the Reverend Andrews Norton might properly be applied to Ross’s doctrinaire classroom style: “Norton came into the classroom, not as one who was seeking the truth, but as one who had already found it.” “His influence on his disciples was very powerful,” one of Ross’s pupils commented. “His insistence on the supreme excellence of his method was a serious weakness in his teaching, for he did not encourage his disciples to think for themselves and showed no interest in their investigations and discoveries.”

Handling original works was essential to Ross’s method, and he often invited students home for dinner at his high-ceilinged, art-filled house on Craigie Street for lessons in connoisseurship and the chance to view the art still en route to museums. His advice to his protégés: fix the best objects of their kind in your mind and keep them there until you run across something more beautiful, be selective and buy only the best, and do not compare different types of objects. After he retired, he continued to take an interest in promising students. Among them in 1928–29 was the newly arrived Laurence Sickman, subsequently the director of the Nelson Gallery in Kansas City, who credited Ross with being his most important artistic influence. Ross recommended to Kojiro Tomita that Sickman be given the run of the MFA’s collection, and Sickman reported that Tomita was “most tolerant and obliging.” Ross also advised Sickman to “learn the language but do not become a philologist, study the art, but do not become an ‘aesthetic.’”

Although he was among the first Americans to collect Monet, Ross lost interest in the Impressionists, deeming them “so superficial when compared with the work of the old masters.” His fierce opposition to modern art—Matisse, Picasso, and the German Expressionists—deterred the Fogg, where he was the keeper of the Ross Study Series and an honorary fellow, from collecting in this area. As a result, with the encouragement of one of the Fogg’s directors, Paul Sachs, Lincoln Kirsten, Edward Warburg, and John Walker founded the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art in Harvard Square, the inspiration for New York’s Museum of Modern Art. As Walker wrote in his memoir, Self-Portrait with Donors, Ross “was as determined as Hitler to prevent the dissemination of what he considered decadent art.”

In 1895, the MFA made Ross a trustee. (He was something of a legacy, since his uncle Matthias Denman Ross was on the founding board.) He thus joined the exclusive club of Brahmin collectors of Asian art: Dr. Charles Goddard Weld, another beneficiary of a China trade fortune, who bought Fenollosa’s personal collection of Asian art and donated it to the museum, and William Sturgis Bigelow. Bowing to the Japanophilia rampant in the MFA’s Asian department, Ross initially collected Japanese art but soon branched out into other parts of Asia, including China, which he visited in 1910 and 1912. His extensive collecting trips were made in the company of his cousin Louise Nathurst, but also with the painter Joseph “Zozo” Lindon Smith, who occupied a large subsidized space on the top floor of the Ludlow, and Hervey E. Wetzel (Class of 1911).

Smith was a painter whose work Ross especially admired, and in return for lessons he underwrote a joint trip to Europe in 1886 so that they might enjoy Europe’s masterpieces together. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship consolidated through travel to Mexico, Europe, and Asia, where they painted side by side. (Ross eventually became a skilled, if academic, painter.) An autumnal letter written nearly half a century later from Venice, shortly before Ross died, reflects on their shared past: “We were in the spring and prime of youth and we were doing some of the best work we have ever done and we have established a standard we have never lost. Florence and Venice we [have] known them as very few people. . . . Italy is no longer what it was. It is spoiled for me so that I shall not come again.”

Edward Forbes, the director of the Fogg Museum, introduced the Harvard student Hervey Wetzel to Ross as “a gentleman of leisure.” The young man evolved from student to protégé to lifelong friend, with whom Denman initially traversed Japan and China, returning via Southeast Asia, India, Egypt, and Europe in 1912–13. Denman laid down the rules: he was to have first refusal. They interviewed dealers and visited their shops. They ignored “archaeological or historical considerations,” preferring to collect the best with the idea that “the aim and end of a liberal education is to feed the imagination, not only by reading the best books but by seeing the best things.”

Described by his mentor as “discriminating and very critical,” Wetzel was “eagerly appreciative and enthusiastic regarding the things that he thought fine and beautiful. His taste and judgment were almost unerring.” Ross had hoped that the younger man, who had inherited the wherewithal to form a major collection, would succeed him as trustee. In 1917, the MFA offered Wetzel the honorary position of curator of Persian art. He planned to devote his fortune and his time to making the MFA’s Persian collection the best in the world. He also bought two adjacent houses on Louisburg Square to house a growing collection that could turn into a small museum. This was not to be. World War I intervened. Rejected for military service owing to a heart problem, Wetzel served as a volunteer at the Paris headquarters of the American Red Cross. Sensing that he might not return, he curated an exhibit at the old Fogg of his collection of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean art. He died in 1918, a victim of pneumonia. The Fogg and the MFA were each bequeathed $100,000 to purchase important works of art. Half of Wetzel’s collection of Eastern art went to the Fogg, and the other half went to the MFA. Among his gifts was the great Wei dynasty Buddhist Votive Stela, dated 554 CE and still on exhibit in the MFA’s China gallery. In memory of his younger friend, Ross gave the MFA a Cambodian statue.

In 1913, Denman Ross donated a large, exceptionally fine Eastern Wei stone bodhisattva (see color plates, figure 4) excavated at the White Horse Monastery at Loyang, in memory of the MFA’s curator, Kakuzo Okakura. Okakura had first seen the sculpture in 1906 in China, where it had just been uncovered. He returned in 1910 hoping to buy it, but the bodhisattva had disappeared, only to surface in the Paris shop of the dealer Paul Mallon, where Ross saw it and bought it.

“Uncle Denman” became a frequent and sometimes intrusive visitor to the storerooms of the two museums. His own collections, which were stored at the Fogg, took up considerable space and were the cause of much curatorial griping. Like Bigelow, he was much given to behind-the-scenes intrigues, weighing in on such matters as the MFA’s collection of plaster casts and its personnel. (One Ross letter to Harvard’s president and ex officio MFA trustee A. Lawrence Lowell began: “The organization of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston is, in my judgment, deplorable.”) At the time, Ross had considerable influence on the running of the museum departments. “There was dear old Denman Ross who never let you get away with anything,” as one curator then working at the MFA ruefully remarked. “After all, Denman practically owned the place at the time.” The Fogg’s curator of Asian art, Langdon Warner, added, “He gloated in his discoveries and would have us know the full merits of the pictures he bought. He boasted and he loved to be agreed with. Still, it would have been a petty spirit indeed who refused that slight offering he asked. Also we found it wise to agree, for it was led by him that we came to realize that Cambodian sculpture, South Indian bronzes, and Coptic tapestries are indeed triumphs in their several fields.” Ross not only advised on acquisitions, he sometimes expressed doubts as to the “maturity” of the judgments of those selecting art, doubts he expressed to Alan Priest, the future curator of the Metropolitan Museum, about to leave with Warner and Horace Jayne (see Chapter Four) on their quest to acquire wall paintings from Dunhuang for the Fogg. Although he was not a stickler for keeping his collection together, he proposed that all labels read “Ross Collection” so that “I shall be able to speak to the people of Boston long after I am dead, as a book written or a picture painted.”

The MFA celebrated its benefactor’s eightieth birthday with a suitable party and by filling nine galleries with a selection of the works that he had donated. On September 12, 1935, in the midst of yet another European collecting trip, he died in his hotel room in London, aged eighty-three. As a fitting final tribute, Yamanaka (the firm from which Ross had purchased The Thirteen Emperors scroll) provided a rare Tang pottery jar to transport his ashes home to Cambridge.

Thus it was that Fenollosa, Bigelow, Ross, and Wetzel attained their goal as collectors: an afterlife through art. It is their legacy that endures in the halls of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

Another landmark in New England’s quest for Asia’s treasures was the opening in 1896 of the Fogg Art Museum. It bears the name of William Hayes Fogg, a native of Berwick, Maine, who prospered in the China trade, heading a shipping company with a presence in five Chinese ports plus two in Japan. He and his wife, Elizabeth Perkins Fogg, traveled widely and collected “Oriental curios.” From his estate, valued at $1.5 million, his widow in 1891 bequeathed $200,000 to Harvard to establish its first art museum, with the couple’s curiosities providing a starter collection. The trustees of the fledgling Fogg were still feeling their way in their new Renaissance-style gallery (designed by Richard Morris Hunt) when, in 1909, they chose as director the relatively young Edward Waldo Forbes (Class of 1895). The museum he now managed comprised a miscellany of casts, Orientalist porcelain, photographs, slides, a few prints, Greek vases, and some English watercolors. The latter were barely visible; as he used to say, the pictures were “in galleries where you could not see, adjacent to a lecture hall where you could not hear.”

All this would radically change during his long tenure. His ancestry helped. Edward Waldo Forbes was a Brahmin from brow to toe; indeed, it was widely remarked that he auspiciously resembled his grandfather, Ralph Waldo Emerson. His forebears included two sea captains who pioneered the China trade, while his father, William Hathaway Forbes, partnered with Alexander Graham Bell in founding the Bell Telephone Company. As a Harvard undergraduate, Edward Forbes came under the spell of Charles Eliot Norton. Forbes then explored Europe and its starred art galleries. In 1903 he became a trustee of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, a position he held for sixty years (a longer reign, his obituaries noted, than Queen Victoria’s).

Forbes was to all intents a proper Bostonian with an educated grasp of the value and importance of great works of art. In his “Methods and Processes of Painting,” a pioneering course in the field of preservation, his students learned to copy Old Masters by working in their styles with identical materials. But he also possessed a restless, unconventional streak. We owe to a family friend, the novelist Helen Howe, a glimpse of Forbes’s other self. In her memoirs, she recalls seeing Forbes “wander into a formal wedding in Milton [Massachusetts], with disheveled hair and mud on his heavy boots, and a fading bunch of wild flowers in his hand, with that vague, seraphic, Emersonian look of another world.” He loved music and played the harp, piano, and cello. At parties on Naushon Island, the offshore sanctuary of the Forbes family and their relations (including Secretary of State John Kerry), Edward Waldo accompanied himself on a guitar while singing old songs, of which (Howe writes) he seemed to have a “boundless supply.” Back in Boston, his persona changed. The premature flower child would negotiate hardheaded deals to acquire for Harvard properties along the Charles River whose potential value, he felt, was unappreciated by university bookkeepers.

The same unconventional Forbes was evident in his choice of his key lieutenants at the Fogg. Two names stand out: Paul J. Sachs, the museum’s associate director, and Langdon Warner, his much-traveled curator of Oriental art. Through both, one suspects, Forbes vicariously savored the less conventional adventures accessible to freer spirits in the art world. With the advent of Sachs (Class of 1900), the Fogg evolved into a boot camp for training a new generation of museum professionals; and through Warner (Class of 1903), the museum mounted high-risk forays into China that triggered the emigration of sculptures and paintings from Buddhist sites, precipitating a debate that still persists.

Paul Sachs instructs the chosen few in his celebrated “Museum Course” in the Naumburg Room at the Fogg Museum (1944).

First, Sachs: In 1915, while seeking a new assistant director, Forbes lured Paul Sachs from his position at Goldman, Sachs & Co., the investment bank founded by his grandfather Marcus Goldman. His father, Samuel Sachs, became a partner with his father-in-law; both families having Bavarian roots. His father intended that his eldest son would become a partner in the family firm, but banking could not rival Paul’s fascination with art. As Paul Sachs recalled, “I always wanted to be an artist, from my earliest boyhood, and instead I went to college. Yet even then my determination did not die. I had started collecting prints and drawings. For 15 years after graduation, I collected and studied, so that some day I could come back to Harvard if the opportunity presented itself.”

Having accepted Forbes’s offer, Sachs settled in Shady Hill, formerly the Cambridge residence of Charles Eliot Norton, with his wife, Meta, and three daughters. Here Sachs taught Fine Arts 15A, the first museum training course offered by any American college or university. The seminar was limited to ten students and usually met on Monday afternoons for three hours, but with supplemental, far-ranging field trips to art-rich cities across the Atlantic. Agnes Mongan, who rose from being Sachs’s research assistant tasked with cataloguing his drawings to become the first female director of the Fogg, recalled how future curators were trained:

Paul Sachs would, seemingly at random, pick up from the wide shelf of the shoulder-high bookcases that lined that long room an ancient coin, a Persian miniature, a fifteenth-century German print, or a carved piece of Medieval ivory, place it in the hand of an astonished student and ask that student to comment on its aesthetic quality, its design, or its possible significance.

Simply being one of the ten students in his soon widely known “museum course” became a door opener for job-seekers in the upper reaches of the art world from 1921 to 1948. Of the 388 students enrolled, at least 160 rose to responsible positions in leading museums, most notably as directors of New York’s Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art, Washington’s National Gallery, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, Chicago’s Institute of Art, San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor, St. Louis’s Art Museum, Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum, and Hartford’s Wadsworth Athenaeum.

Sachs’s students brought to their calling not just a concern for scholarship and conservation but also a passion for acquisition of original works. They learned to handle and scrutinize the Fogg’s treasures, thereby developing the trained eye of a connoisseur (long before that term became anathema to postmodern curators, to whom the word reeks of elitism and exclusion). This very much accorded with Edward Forbes’s determination (in Sachs’s words) “to make of the Fogg not only a treasure house, but also a well-equipped setting adapted for teaching purposes, that he meant it to be a workshop as well as a place of inspiration for undergraduates and mature scholars. Free from the craze for size, uncompromising when it came to quality, Forbes understood sooner than others the importance of confronting students with original works of art.”

There was crucial corollary. From the 1920s onward, it became evident that a curator/director’s rise commonly hinged on collection growth. In this respect, East Asia was a bargain hunter’s paradise. For Director Forbes, this was not merely an aesthetic or ethical matter; it was also linked to an immediate practical problem. In 1923–24, Harvard approved a $2 million fund-raising campaign to replace the Fogg Museum’s existing and cramped building with new and spacious quarters. This meant that more premium works would be needed for display in galleries due to open in 1927. Paul Sachs became the principal fund-raiser for the Fogg’s expansion and its expeditions. Though only five-foot-two, balding, and egg-shaped, he disarmed with his confident certainty and his insider gossip. He worked closely with Forbes, so much so that the pair was nicknamed “the Heavenly Twins.” As the director’s daughter, Rosamund Forbes Pickhard, recalled in a 1995 interview, “They were a real team of comedians together. They’d rush at [buying] newspapers, saying ‘Are there any deaths’?” (Funerals were prime fund-raising opportunities.)

Both money and artworks flowed in. As a team, they worked well together. Forbes’s sweetness and indecisiveness were balanced by Sachs, who was direct and forthright. As President Lowell of Harvard recalled at the opening, “If it hadn’t been for the superb mendacity of Messrs. Forbes and Sachs, why the place wouldn’t exist.”

Still, it was not simply mendacity that enabled the Fogg Museum to fill its half-empty galleries and thus put Harvard’s seal on the art and antiquities streaming from Asia. Even more potent was the Crimson mystique, especially when enhanced by ancestry and classroom epiphanies, as in the case of Grenville Lindall Winthrop (Class of 1886). In 1943, he bequeathed to the Fogg what is probably the country’s finest collection of archaic Chinese jades and bronzes (see color plates, figure 3), along with an array of nineteenth-century American and European paintings and drawings. His donations, totaling some 4,000 works, was credibly reckoned as the largest gift of its kind to any American university. It was quintessentially emblematic: Grenville was the direct descendant of John Winthrop (1588–1649), the first colonial governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony; he was engagingly eccentric, a gifted Berkshire landscape architect who wintered in a New York town house a block from the Metropolitan Museum (with the Winthrop crest proudly posted over the doorway). Here for many years his apartment was an obligatory stop for Sachs’s connoisseurship students—with the collector sitting anonymously nearby to appraise their response.

As a species, collectors tend to be odd fish. Some cluster in schools, but truly interesting are the solitary swimmers who by choice seek remote and challenging latitudes. Grenville Winthrop was such a loner. As a Harvard student, he was among the many smitten by Charles Eliot Norton, the humanist titan who initiated art history as an academic subject. As Edward Forbes recalled, “If you asked anyone who was at Harvard during these years [from] what courses he received the most, the answer most probably would be, ‘From Professor Norton’s fine arts courses.’ Though there were loafers and athletes who took the courses because they heard they were easy to pass, even for them I think it was a case of ‘and those who came to scoff remained to pray.’”

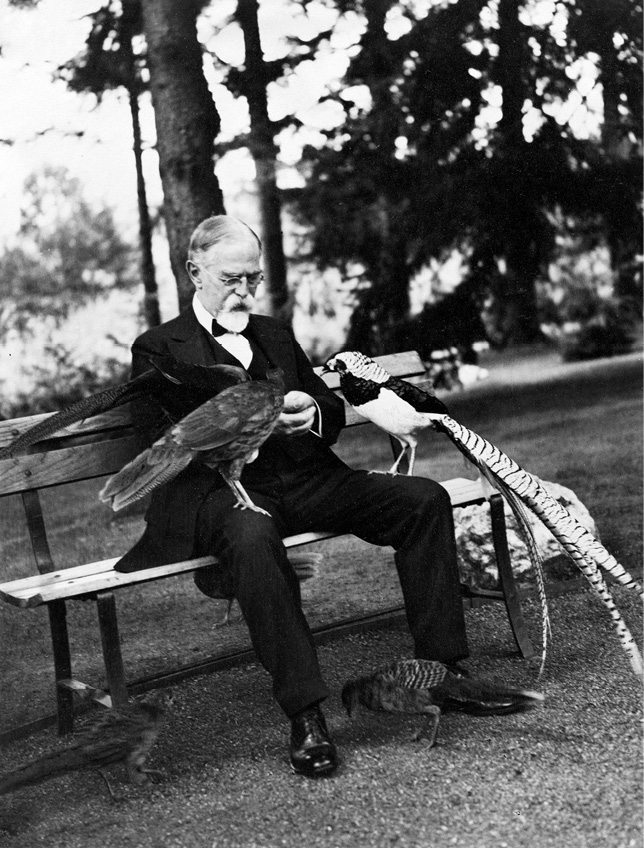

Grenville Winthrop, who endowed the Fogg with world-class jades and bronzes, here meeting with avian friends in his garden at Groton Place, Lenox, Massachusetts.

Winthrop went on to earn a law degree at Harvard, but neither the bar nor business mattered as much to him as the allure of art, ignited by Norton and intensified by Martin Birnbaum, “a lawyer by training, an art dealer by vocation, and a violinist at heart.” Together they explored both contemporary Western works and the rarified realm of Chinese jades and bronzes. In his 1960 autobiography The Last Romantic, Birnbaum imagined the elderly Winthrop at home: “After a lonely dinner, chiefly of fruit and vegetables, he would read some favorite book, or work on a card catalogue of his treasures. . . . Proust could have done the scene justice. The quiet cork-lined rooms [were] disturbed only by the chimes of a fine collection of grandfather clocks . . . and while their delicate peals vibrated through the house, the master would move about the shadows hanging his drawings or cataloguing them, or rearranging the Chinese jades and gilt bronzes.”

It is fair to say that Grenville Winthrop was a recluse who looked inward for the rewards of savoring art in general and Chinese antiquities in particular. But others in the same stream were ebullient extroverts. Indeed, no one better personified the ambiguities of the passion more abundantly than Langdon Warner (Class of 1903).