“The British, the French and the Germans and the Russians have so added to our knowledge of the history of the human race, and incidentally enriched their museums with artistic monuments brought back from Turkestan [current Xinjiang province] that it has become almost a matter of reproach that America has contributed nothing in that direction.” Thus did Langdon Warner, then director of the Pennsylvania (now Philadelphia) Museum of Art and future curator of Oriental art at Harvard’s Fogg Museum, announce in 1922 the advent of a new American collecting spree in China. He ended on an upbeat note: “Little time would be lost in working an unproductive site, the field is so vast and the information we seek is so varied, that the chance of complete failure seems reduced to a minimum. Fully as much should be done above the ground as below it.”

A tall, blue-eyed redhead, Langdon Warner was an appealing, Spielbergian adventurer-cum-scholar who, during the 1920s, led two hunting and gathering trips to China for the Fogg. With his trademark boots, Stetson hat, rakish mustache, and swashbuckling demeanor, he is said to have been one of the models for Indiana Jones. Yet by birth and breeding, Warner was not a cowhand but a blood-proud Brahmin descended on his mother’s side from Sir John Dudley, Royal Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and also (with dialectical symmetry) from Roger Sherman, the sole Founding Father to sign the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. His uncle was Senator George F. Hoar (Republican from Massachusetts). After entering Harvard (Class of 1903), young Landon rowed, became an editor of The Harvard Advocate and a member of the Hasty Pudding Club and the Signet and Memorial Societies, and was named class poet. After graduation, he married Lorraine d’Oremieulx Roosevelt, a daughter of Theodore Roosevelt’s first cousin, at the Roosevelt compound in Oyster Bay, New York.

Boy’s Own archaeologist: Harvard’s Langdon Warner in China.

His apprenticeship began in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts under the tutelage of Kakuzo Okakura, a Japanese Buddhist who always dressed in kimonos and is now principally remembered as the author of The Book of Tea (1906). Warner revered Okakura as his sensei, or master. It was during his MFA years, when the museum assembled the finest collection of Asian art in North America, that Warner sharpened what were to prove his two strongest interests: Japanese and Buddhist art. He made his first study trip to Japan in 1906, but his apprentice spadework really began when he joined the explorer-geologist Raphael Pumpelly’s expedition to Turkestan in 1904. He was part of a team that included the climatologist Ellsworth Huntington and the German archaeologist Hubert Schmidt (who had been trained at Troy), under the versatile leadership of Pumpelly, a physiographer and surveyor.

In 1913, having left the MFA, Warner toured Asia by way of Europe to test the feasibility of establishing in Peking a school to train archaeologists, indigenous as well as foreign, broadly similar to American academies in Rome and Athens and to the École francaise d’Extrême-Orient in Indochina. Both the idea and the trip were the inspiration of the Detroit millionaire Charles Lang Freer, but his enlightened plan became an instant casualty following the outbreak in July 1914 of World War I. On the eve of America’s entry in April 1917, Warner had been named director of the Pennsylvania Museum of Art. He was granted leave to serve in Siberia as a vice consul in Harbin, where, following the Bolshevik revolution, he became the State Department’s liaison with the anti-Bolshevik Czechoslovak Legion, then struggling to exit Russia via the Trans-Siberian Railway. (Warner crossed Siberia four times, and one of his favorite stories concerned his witnessing the proclamation of the White Russian Admiral Alexander Kolchak as ruler of Eastern Siberia in a baggage car.) All this contributed to his Crimson-enhanced self-assurance while searching for Buddhist treasures and navigating among warlords and bandits during China’s chaotic 1920s.

But first, the context: “Archaeology is not a science, it’s a vendetta.” Sir Mortimer Wheeler’s oft-quoted admonition was inspired by his own experience as director of the Archaeological Survey of India and excavator of Bronze Age cities in the Indus Valley. From the final decade of the nineteenth century until the outbreak of World War II, China and much of Central Asia became a dueling arena between rival national art-seeking expeditions. European and Japanese teams, armed with the latest survey and photographic equipment, began combing western China, particularly along the old trade routes known as the Silk Road.

It was the publication of their finds that prompted the Fogg Museum’s first “scouting trip” in 1923–24 to Dunhuang (“Tun-huang,” in Warner’s rendering) in Western China’s Gansu (Kansu) Province. To lead its entry into the field, Director Edward W. Forbes turned to Warner and another Harvard man, Horace Howard Furness Jayne. The heir to a patent medicine fortune, “Hoddy” Jayne coauthored the lyrics of the Hasty Pudding Club’s 1921 play Wetward Ho! [sic], a spoof on Prohibition, and swanned about Cambridge in his trademark coonskin coat and patent-leather pumps. He graduated to a job as curator of Oriental art at the Pennsylvania Museum of Art, where he became “the presiding genius at Memorial Hall.”

Resisting parental pressure to hold on to his secure post as the museum’s director, always averse to administrative chores, and anxious to earn “a name in the field,” Warner eagerly embraced Forbes’s offer. In seeking funds for the expedition, the director assured potential donors that Harvard possessed “records of certain sites of the early trade route [i.e., the Silk Road] which make it virtually certain that important artistic and archaeological treasures are awaiting to be brought to light.” A sum of $46,400 was raised from subscribers—a miscellany of Forbeses, Sachses, Walters, Warburgs, Cranes, and Rockefellers—many of them friends and relatives of Paul Sachs. Although Sachs downplayed great expectations, cautioning that “Mr. Warner may bring back little or nothing,” he added a soupçon of optimism: “or he may bring back one hundred times, or one thousand times the value of the money that was put into it.”

Once in China, Warner and Jayne sat in their drab hotel in Peking amid maps, medications, typewriters, photographic equipment, and weapons (a shotgun and an automatic pistol), contemplating the problems that lay on their route to Xi’an (Sian), site of the ancient Chinese capital of Chang’an. In Warner’s summation: “Bandits on the Honan border and to the west of it; Mohammedans violent in Kansu and possibly to the west of that; rains and seas of mud at first—then droughts and bitter desert cold.”

The initial train trip to Honan (Henan), went easily. There they met the local warlord Wu Pei Fu and thirty members of his staff who dined with the pair while a band rendered military airs. The marshal, known for taking “no back-talk from Peking,” provided them with a ten-man armed escort for the next leg of their journey. Accompanied by an interpreter, Wang Jinren, and a cook called “Boy,” the expedition announced its nationality with an ersatz American flag, stitched together by four local tailors, which adorned their mappa, a springless two-wheeled cart. The team then set out for Xi’an, the former capital of the Qin empire.

Warner and Jayne spent four September days at Xi’an, delighting in the pleasures of rustic hot-spring baths, rummaging among local curio shops, buying a series of rubbings bearing the vermillion seal of the late murdered Viceroy Duanfang, as they obtained introductions to officials and information about the road ahead. Still flying the Stars and Stripes but leaving their armed escort behind, they departed the former capital and its surrounding earthworks, known even then as a rich source of antiquities (and forgeries). “Before many years are gone, either the grave robbers will have ploughed their clumsy way through these mounds again, to recover for the foreign market what their predecessors left; or scientists, by special permit, will be allowed to come with their measuring tapes and their cameras to open in all reverence those kingly tombs by the river Wei.” Thus Warner lamented in The Long Old Road in China, his 1926 account of the expedition: “To pass among these mounds scattered as far as the eye could reach, big and little, near and far, was an experience in self-restraint for the digger.” (This was the area where farmers, while digging a well in 1974, came upon the first of the Qin emperors’ terra-cotta armies, buried two millennia before.) After “some fifteen miles of temptation,” Warner and Jayne proceeded west to Chinchow (Jinzhou) at the junction of the Ching River, where they “fetched” some sixth-century Buddhist stone sculptures—mostly heads and a torso—that they found “knocked from their places in the Elephant Chapel.”

During the lawless 1920s, bandits and warlords proliferated in China’s western regions. Before they set out on the seven-day march from Honan to Xi’an, Warner wrote that “there had been six murders, thirty kidnappings, and countless holdups.” Now the province was swarming with government troops poised for a counterattack. In a forewarning of dangers that impelled Jayne to strap an automatic revolver to his hip, the pair witnessed the summary execution of three bound prisoners, whose “three heads rolled off from three luckless carcasses as the soldiers shuffled on, leaving the carrion to be swept up.” Now the Americans approached Lanchow (Lanzhou), Gansu’s provincial capital, wading through waist-high, solid black mud. Just as they pulled up at their inn’s gate, government soldiers attacked their small caravan and “commandeered carts, drivers and mules,” claiming them “for military purposes.” Warner demanded to see the amban, or local magistrate: “Remembering that I had once been red-headed, I permitted myself the luxury of a real scene, realizing that nothing else would do any good. . . . At the yamen gate I yelled at the top of my shout and sent in my card. His Excellency was in bed. Well, tell H.E. that it was time to get up. H.E. was in bed! Well, tell H.E. that in another minute a foreign devil would come in and help him dress.” In five minutes, the magistrate turned up. Alternately threatening and cajoling, Warner presented H.E. with a letter from Field Marshal Wu. “At the mention of that great name, H.E. nearly wrung his hands off short at the wrists”—which produced the desired result: their property was returned.

The Caves of Dunhuang (1924), as photographed by Warner—a magnet for adventurers, monks, and gatherers of Asian art.

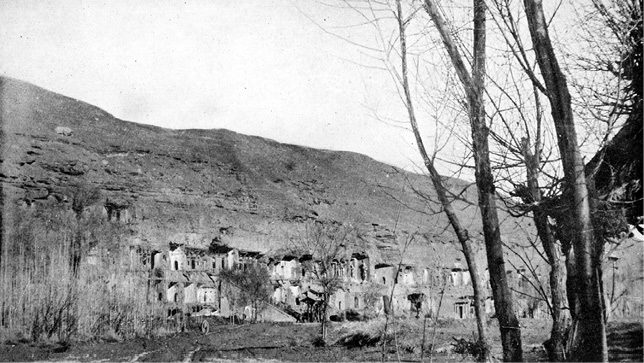

Their final objective was Dunhuang, but en route they made a detour to the ruins of Kharakhoto, “the black city of the Tanguts” on the Sino-Mongolian border in the Gobi Desert, the ruins that Sir Aurel Stein identified as Marco Polo’s Etzina (Edsina). The Russian explorer Colonel Pyotr Koslov had rediscovered the remnants of the city six years before Stein in 1908. A center of Buddhist art, its walls, in Stein’s description, still rose “in fair preservation amidst the solitude of a gravel desert, girdled by living tamarisk cones & two dried up branches of the river.” The Tanguts, a people of Tibetan-Burmese origin, succumbed to Genghis Khan’s Mongols in 1226, but the site was only abandoned to the desert a century later after the Ming armies reduced the city to ruins by damming and diverting the river Etzin-Gol. Preceding the Fogg team by more than a decade, Koslov and Stein discovered a trove of Buddhist sculptures, manuscripts, and painted texts that the arid sands helped preserve (now in museums and libraries in St. Petersburg and London).

Upon his arrival, Warner gazed at the melancholy desolation, describing the place “as lovely beyond all my imagination” and deserted:

No city guard turned out to scan my credentials now, no bowman leaned from a balcony above the big gate in idle curiosity, and no inn welcomed me with tea and kindly bustle of sweeping out my room or fetching fodder for the beasts. One little grey hawk darted from her nest high in the grey wall, her set wings rigid, and sailed low over the pebbles and sparse thorn bushes of the plain. No other life seemed there, not even the motion of a cloud in the speckless heaven nor the stir of a beetle at my feet. It was high afternoon, when no ghosts walk. But, as sure as those solid walls were built up by the labor of men, just so sure was I that the little empty town had spirits in it. And the consciousness never left me by day or night while we were there.

In spite of the isolation of the site, they found that Stein and Koslov had “cleared every wall and gutted every little sealed pagoda.” With four diggers, along with a guide and some camels, they nevertheless excavated for ten days, finding fragments of Buddhist wall paintings, small clay ex-votos in the form of stupas, a fine bronze mirror dating (as Warner believed) to the tenth century, plus several small clay sculptures and miscellaneous pottery when a snowstorm stopped their work. (A few years later, an envious Warner would learn from a friend and Mongolian expert, Owen Lattimore, that the Swedish archaeologist Folke Bergmann “was able to camp and dig for months, not only at Khara-khoto but all along the Edsin Gol and along the Han limes. Got some very fine stuff.”)

When leaving Kharakhoto, the pair’s disappointment turned to disaster when their guide lost the way and, on Thanksgiving night, Jayne’s feet froze. When he dismounted from his camel, he fell over, unable to stand. For three hours Warner and Wang scrubbed his feet with snow and grease until his feeling was restored—and Jayne fainted. With Hoddy’s feet an enormous mass of blisters and his legs swollen to the knees, Warner feared blood poisoning and the likelihood of amputation as fever and infection finally set in. It was impossible to proceed, and Wang was sent ahead to find a cart on which Jayne could be placed in his sleeping bags fortified by opiate pills. After a ten-day detour through icy winds across the snow-covered ground along the river, they finally reached Kanchow, where they consulted the local Chinese missionary doctor, who plied Jayne with antiseptics.

After sixteen days’ rest, they started out for Suchow, where, after a four-day stay, they came to a “momentous decision.” Jayne, despite his determination, was still unable to walk more than a hundred yards. He would therefore return to Peking with several cartloads of spoils and supplies that they had gathered and stored along the way, while Warner would proceed to Dunhuang, accompanied by secretary-interpreter Wang, the carters, and four ponies. At the crossroads of Anxi, where the road branched south, they parted. Dunhuang lay some seventy miles across the desert.

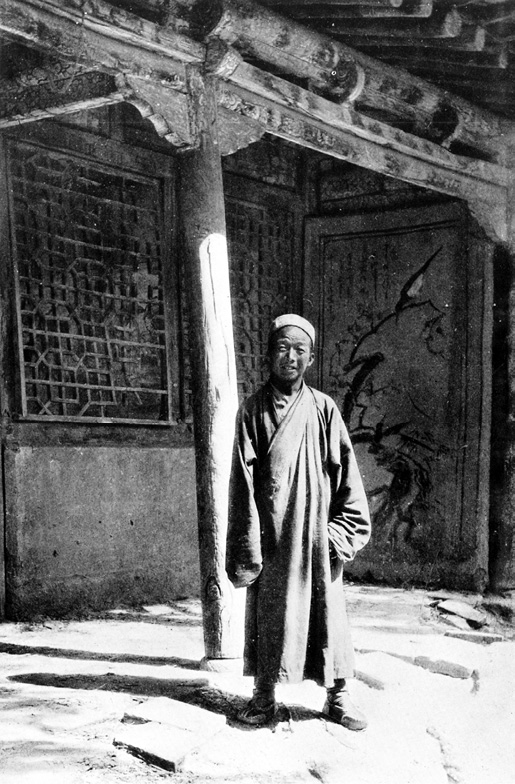

In its heyday during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), Dunhuang had been a flourishing entrepôt for the Silk Road and a center of Buddhist worship. There, in 1907, Sir Aurel Stein, a Hungarian-born scholar and archaeologist working for the government of India and the British Museum, purchased from a Daoist monk, Wang Yuanlu, 6,500 documents and paintings on paper and silk (twelve packing cases in all, including the Diamond Sutra, the world’s oldest dated printed book [868 CE], for £130, or approximately $650). The Daoist monk had been the chance discoverer in 1900 of the so-called Library Cave, and some of the items had already been dispersed, finding their way into the hands of local officials before the provincial government ordered the restoration of the objects to their original cave. By the time Stein arrived, the objects were safeguarded by a locked door in front of the cave, with Wang as keeper of the key.

Sir Aurel spent nearly three months in the precinct of Dunhuang and the Mogao caves negotiating the sale, but local unrest and an outbreak of diphtheria forced Stein, already suffering from fever and a severely swollen face, to leave. Wang was persuaded to sell Stein some of the contents of the Library Cave “on the solemn condition that nobody besides us three [Wang, Stein, and Stein’s Chinese secretary, Jiang Xiaowan] was to get the slightest inkling of what was being transacted,” and the origin of these “finds” was not to be revealed to “any living being.” On May 29, Stein’s party spirited away the collection on two nights, avoiding the local supervising soldiers by the screen of a steep riverbank. Stein’s offer to buy all the manuscripts had been refused by Wang, and it was Paul Pelliot, the great French Sinologist, working for three weeks in the same cave in 1908, who acquired a further eight thousand items for the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris for 500 taels, or $450. The news of these finds would cause a sensation, unsurpassed in archaeology until Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922.

The keeper of the Library Cave in Dunhuang, Daoist monk Wang Yuanlu.

Pelliot, who taught at Harvard during the late 1920s, had alerted the Fogg to a Dunhuang collection he was “particularly anxious to have acquired by some serious museum in the West,” that is, what he and Stein had left behind. Writing to his patron, Charles Lang Freer, in 1916, Warner already had Dunhuang in his sights: “We must have some frescoes in this country for study. . . . They are almost the only things we dare not send native collectors after. They would certainly destroy more than they brought out, also we must have perfect records of their position and appearance before removal.”

At the Fogg, Forbes readily acknowledged that the results of the “scouting trip” might be “wholly on paper, as to separate sculptures from the living rock would be a vandalism.” However, he did not disapprove of Warner’s scheme of removing paintings, for which there had been a precedent. Between 1902 and 1914, members of four German expeditions led by Albert Grünwedel and Albert von Le Coq sawed off paintings from the walls of caves along the northern Silk Road.

Warner reached Dunhuang on January 21, 1924, where he found the chapels “perhaps more impressive than any paintings that I’ve ever seen.” But confronted by the hundreds of painted images in the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, he succumbed to doubts: “Neither chemist nor trained picture restorer, but an ordinary person with an active archaeological conscience, what I was about to do seemed both sacrilegious and impossible.” Nonetheless, while in the presence of Wang Yuanlu (the same caretaker who sold the manuscripts to Stein and Pelliot), Warner applied cloths soaked in barrels of thick glue in overlapping layers on the walls, which, when dried and peeled off, allowed him to remove wall painting fragments from six caves.

With the Germans in mind, Warner’s preliminary report to the Fogg claimed that they were “the first paintings removed without being seriously marred by saw marks, and they are undoubtedly of an aesthetic and historic value equal to any Chinese paintings which have hitherto come to this country.” He described his psychological battle with the monk Wang, which ended with Warner’s “abandoning subtlety and asking straight out for fresco fragments.”

Warner wrote of the considerable difficulties in the freezing weather of removing the art from the cave wall: “The milk froze on the wall instead of penetrating even when I thinned it with hot water. The glue cloths cooled before I got them in place and altogether I have small hopes.” He finally squeezed them between alternate layers of felt and paper tied with rope. All this cost $150 donated to Wang: “merely a large tip that covered food and horse-fodder and services for my soul, duly conducted by the priest. I like to think of the Fogg Museum paying for the last mentioned—especially when I am out of reach of the college chapel.”

The Removal of the Bodhisattva from Cave 328 in January 1924 by the first Fogg Expedition.

But the real gem from Dunhuang would prove to be a three-and-a-half-foot-high polychrome Tang bodhisattva, which had to be hammered from its base. Warner recalled spending “five days of labor from morning till dark and five nights of remorse for what I had done and of black despair.” He wrapped the bodhisattva lovingly in his own underclothes before lugging it off in his cart for the eighteen-week journey back to Peking. “If I lacked for underwear and socks on the return journey,” he reported, “my heart was kept warm by the thought of the service which my things were performing when they kept that fresh smooth skin and those crumbling pigments from harm.” After questioning Wang and his acolytes and “ransacking” the Library Cave, Warner and his translator determined that there were no more leftover scroll paintings or manuscripts and left for home.

Warner’s oft-repeated justification for his removal of the art was that the Dunhuang caves were inaccessible and had already been damaged. In the nineteenth century, the caves had been marred in Muslim uprisings, and Stein and Pelliot both maintained that the portable objects would be safer in London and Paris, presaging similar justifications by future American collectors and curators. As Warner lamented in a letter to his wife, “[E]verywhere eyes are gouged out or deep scores run right across the faces. . . . Whole rows of maidens in elaborate headdresses pass you by—but you look in vain for a complete head. Elaborate compositions of the bodhisattva enthroned among the elder Gods with a lovely nautch girl dancing on a carpet before Him contain not a single figure that is complete. . . . But across some of these lovely faces are scribbled the numbers of a [White] Russian regiment, and from the mouth of the Buddha where he sits to deliver the Lotus Law flows some Slav obscenity.”

Warner attributed the Slavic graffiti to the indifference of the Chinese, writing to a friend, “As for the morals of such vandalism, I would strip the place bare without a flicker. Who knows when Chinese troops may be quartered here as the Russians were? And, worse still, how long before the Mohammeddan rebellion that everyone expects? In 20 years this place won’t be worth a visit.”

Still, in his official report to the president and fellows of Harvard, Warner made no mention of the removal of the paintings. At the Fogg, the paintings passed to Daniel Varney Thompson, a student of Forbes and a conservator who had advised Warner on the “strappo technique” whereby the painting surface was stripped from the wall, a process he had used on European frescoes. In a 1974 interview, Thompson acknowledged that his attempts at conservation of the Dunhuang paintings were only modestly successful: “Langdon, instead of using a thin, rather weak glue, had used a glue so very thick as to be almost unmanageable. The wall was cold and the glue had set immediately to a jelly.” In Thompson’s report, as quoted by a later conservator, Sanchita Balachandran, he cited the case of the Bust of an Adoring Figure, “the intelaggio [the pieces of cloth] came away with unusual ease and brought no color whatever with it [but] . . . there was . . . less color than was expected.” In fact, the face of this figure is entirely missing. A figure of a dancer, considered the “most hopeless case,” was too damaged to be accessioned into the Fogg Collection. After two attempts at liberating the layers of paint from its intelaggio, Head and Shoulders of a Buddhist Figure was left unfinished because “the identity of the picture was entirely destroyed.”

Owing partly to Warner’s gifts of persuasion, the Fogg’s first expedition was judged a success by Sachs, Forbes, and its financial backers. On the basis of its limited results—statuary, rubbings from Xi’an, the fresco fragments of Dunhuang, photographs of various caves—the museum’s management persuaded the trustees of the estate of aluminum millionaire Charles M. Hall, who had been a collector with an interest in China, to underwrite at the cost of $50,000 another foray to western China in 1925. The trustees of the estate were primarily interested in funding what the Fogg and Warner referred to as “the Big Scheme,” a plan for cooperation between Chinese and American scholars, which would eventually bear fruit in the founding in 1928 of the Harvard-Yenching Institute, dedicated to the promotion of higher education in China. Nominally, Warner was again leader of the expedition, although he remained behind in Peking seeking possible Chinese partners for the Big Scheme.

Jayne now headed the team that had been spending months in Peking learning Chinese. As their leader explained, he did not want to “head the new group unless he knew the language reasonably well,” which in his case included learning “ancient Chinese curses in a number of Chinese dialects.” He also amused himself with having himself tattooed on every available inch of his body, making him “an amazing sight in a bathtub.” Finally setting off from Peking, Jayne and company headed to Dunhuang with the aim, not divulged to Chinese authorities, of removing more paintings. Besides Jayne, the new team included Alan Priest, future curator of Asian art at the Metropolitan Museum; the conservator Daniel Thompson; a surgeon, Horace Stimson; and a photographer, Richard Starr. Warner was then forty-four; the other Americans were in their twenties.

In Peking, Warner had been able to obtain formal permission only for study and photography at Dunhuang, and was “warned most emphatically . . . that nothing can be removed from the chapels.” But the size of the expedition, the presence of Thompson (an expert in fresco removal), and the correspondence between Jayne and the Fogg, clearly indicate that their plans went far beyond creating a photographic record. They discussed the removal of entire scenes from one or more caves. The most audacious solution was “the aeroplane proposition” initiated by Thompson, whereby installments of material were to be sent on a monthly basis to headquarters near Peking: “Ten or twelve hours in an aeroplane are a far safer bet than three months in a cart,” he wrote to Alan Priest, who forwarded the proposal to Paul Sachs. “Most important of all, is the fact that we should get each installment of transferred stuff safely put away, out of the reach of rivals or bandits. . . . The sculpture could be carried perfectly in an aeroplane, whereas in the long journey by road it might all go to bits.”

An early intimation of trouble occurred on March 25, a month’s distance from Peking and eight weeks’ travel from Dunhuang. As reconstructed by American University’s Justin Jacobs, Jayne and his party, accompanied by Wang Jinren, their interpreter, and a Chinese scholar from Peking’s National University, Dr. Chen Wanli, encountered an angry mob of Chinese peasants at Jingchuan, a small village near the Luohan Caves in Gansu Province. According to Chen’s published diary, twenty or so villagers “grabbed the reins of the horses firmly and would not let us leave.” More villagers arrived, “making a big ruckus,” and they “accused Jayne of breaking some Buddhist statues.” The crowd swelled until cash was produced, amounting to two dollars each for one large and eighteen small statues. No sooner had the negotiations concluded than the local magistrate appeared. The deal was voided and the money returned.

The rising anger against the “foreign devils” was fueled by an incident that had just occurred in Shanghai on May 30, 1925, while the Fogg team was en route to Dunhuang. During a strike against a Japanese-owned cotton mill, factory guards fired upon the strikers, killing a worker. Shanghai’s British-dominated police force declined to prosecute the managers responsible. A massive student demonstration followed on the Nanking Road, facing the city’s international settlement. British police fired on the crowd, killing at least eleven demonstrators and wounding many others. Anti-foreign protests leaped across China; missionaries and foreigners were evacuated; and in the ensuing turbulence, which persisted for months, hundreds were reported as dead or wounded.

This was the setting as Jayne’s team arrived at Dunhuang. They were immediately encircled by a mob of angry demonstrators escorted by “a guard of mounted riflemen.” Jayne sent this warning to Warner: “After you had left last year the populace was exceedingly displeased with what had been removed, had raised a fearful row and accused the magistrate at TH [Dunhuang] of accepting a bribe to allow you to take things away, and in consequence thereof he had to be removed from office.” Warner thus remained at Anxi, three days’ distance from Dunhuang, adding, “[I]f I had been there this time, the situation would have been far worse.” He now feared “that the few fresco fragments and the mud statue which the Priest gave me last year had grown into whole chapels robbed by me. . . . I was responsible for famine and drought.” As Jayne reported to Forbes at the Fogg: “I came to the conclusion that it was folly to attempt to remove any frescoes.” Circumstances had changed since the team’s previous trip: “[I]t was a very different matter to remove a few fragments of damaged frescoes which could be done swiftly without attracting attention or causing undue distress among the monks or local people, compared with attempting to take away one or more complete caves, a matter of three or four months work at least which would inevitably attract great local attention and probably actual disturbances . . . we would probably have gotten into an equal amount of hot water, besides thereby jeopardizing future expeditions, either sent out by the Fogg or, which would be even worse, by the Big Scheme.”

With the caves fifteen miles from the town, the trip through deep sand was by necessity in daylight, and under guard. It took nearly five hours each way. This allowed for only a few hours on three days, or about ten hours total, of study and photography but with no flashlights allowed. Thus the “foreign devils” barely escaped with their lives, and with “no results” save for a few photographs of caves they passed along their route. Years later, in 1987, in A Latterday Confucian: Reminiscences of William Hung, the American scholar Susan Chan Egan revealed that the expedition had been betrayed by its secretary-interpreter Wang. Wang had confessed to Hung (Hong Ye), the American-educated dean of Yenching University in Peking, that he was present when Warner on his first visit removed the paintings from the caves. Hung contacted China’s vice minister of education, who then notified officials all along the team’s subsequent route that they should provide protection but “on no account allow them to touch any historical relics.”

In 1930–31, a final Fogg expedition, this time led by Sir Aurel Stein since Warner was by then persona non grata, was once again blocked owing to Hung’s intercession. Headlines of the Tianjin paper L’Impartial (Dagongbao) claimed that Stein’s mission was to plunder Xinjiang’s antiquities. The newly founded Chinese National Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities denounced Stein as a vandal and protested that Western institutions were depriving the “rightful owners, the Chinese, who are the most competent scholars for [the] study [of Chinese materials]” of the opportunities of ownership. Fearing that Stein’s expedition would jeopardize the future of the Big Scheme, the recently founded Harvard-Yenching Institute called for Sir Aurel’s recall.

His expedition-leading days over, a frustrated and remorseful Warner returned to the Fogg as its curator of Oriental art until his retirement in 1950. Noting that Warner, reluctant to leave Cambridge, had turned down a position at the Met in 1927, a position then offered to Alan Priest, Sachs wrote Forbes a memo that summed up their curator’s assets: “Even though you and I know that he is not the best man in the world for office routine or teaching routine or any kind of routine, he is none the less such a vivid person; such a good friend; and such an attractive asset for the long future, that I think it is fortunate that he prefers us to the Met.” Exchanging his archaeological garb for Cantabrigian baggy tweeds, he never ranked as a full professor but was a popular lecturer at Harvard teaching “Chinese and Japanese Art,” one of the first courses in this relatively new field offered in America. At the end of his trial run, he “gave a luncheon with beer to twenty youths who took it for a snap. We used to have bully séances in the Art Museum looking at the storage and grinding up the exam together. I told them all the examination questions beforehand, which they thought would simplify life, but it proved to be not so much help as they had thought.”

His own writing was distinguished by witty asides, slang, and clarity of thought. He viewed “glittering generalities” as an abomination; his offending students risked finding the comment “glit.gen” penned in the black squid ink their teacher favored. He maintained a lifelong interest in archery and falconry and spent his spare time whittling wooden eagles. A great conversationalist, he was an ornament of two of Boston’s Brahmin haunts—the Tavern and the Saturday clubs, patronized by equally distinguished Harvard alums. At Christmas dinners at the Tavern, Warner led the carols “to lift the rafters and make the candles gutter.”

Warner served in the military during World War II, and it was claimed—although denied by him—that in rushing to the White House after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Warner was able to persuade President Truman to save the Japanese cities of Nara and Kyoto from bombing. His role, he said, was merely to provide maps detailing cultural sites, but the decision of where to bomb was not his. Nevertheless, the Japanese erected two monuments honoring him in the two cities and posthumously awarded him the Order of the Sacred Treasures, second class, the highest order that may be bestowed on a foreigner. He was also awarded an audience with His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Hirohito:

Yesterday I had an audience with H.I.M. It was remarkable for its brevity. . . . It was the first of its kind and therefore impossible. H.I.M. was most cordial, set me in a chair near him and seemed to understand all my English before it was translated by the Chamberlain. In fact the translation wasn’t necessary on either side except for the fact that I don’t know the special court forms of address and should have tu toi-ed him quite innocently. . . . At the end he said the weather was very hot and I must take care of my health. (I was clad in a black felt coat bought in London for the Royal Academy lecture, and sponge bag breeks) and no doubt I looked kinder flushed, especially as I knew that no samurai would mop his brow in the Presence, and I have some expanse of brow to mop.

Upon his death, the grateful Japanese held memorial services in Kamakura, Kyoto, and Nara. At the monastery of Engakuji in Kamakura, photographs of Warner were displayed while a dozen Zen priests chanted a chapter from the Lotus Sutra.

Yet in China, ignoring the extenuating circumstances, Warner has been deemed a plunderer. At a 2004 conference at Dunhuang, the director of the Dunhuang Academy, Fan Jinshi, requested the return of all objects taken from the site. This seems unlikely, since they are scattered in dozens of collections around the world. The Fogg maintains that they paid in full for Warner’s artifacts, as proved by receipts.

Warner operated in a different era, one in which objects were carried off, with great difficulty, and with the stated justification that they were being neglected and vandalized by the Chinese. And it was their appearance in Western collections, ironically, that stimulated today’s preservationist initiatives. In a positive epilogue to a contested history, in 1994 the International Dunhuang Project began digitalizing material and now provides online access to thousands of images in an extensive searchable database. The project, involving a partnership of six museums and libraries, records materials not only from the Caves of a Thousand Buddhas but also from other sites along the Silk Road. Conservators in London’s British Library restore the manuscripts in climate-controlled facilities, removing the backings, paste, and frames left by previous generations.

When we were last in Cambridge, Harvard’s Arthur M. Sackler Museum, where the Fogg’s material now resides, was closed for renovation, but on an earlier visit only the bodhisattva and two painting fragments were on exhibit; none of the art collected by Warner was listed among the objects featured in James Cuno’s Harvard’s Art Museums: 100 Years of Collecting. Yet the museum’s conservation staff, benefiting from knowledge gained from the Dunhuang restorations, helped oversee and assist the exhibition of Asian wall paintings at other major museums, including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Penn Museum of Art. As for the caves, when we visited them in 1995, we discovered that white rectangles and darkened glue drips remained where the paintings were removed—as the shaming guides invariably point out to foreign tourists.