Imagine you are an adventurous traveler, destination China, in 1923. On leaving Peking, outfitted with maps, saddlebags, canteen, tin cup, camera, flashlight, and passport, you are warned about bandits on the border, then given precautionary advice on whether to pack a shotgun or automatic pistol. Finally you board the Ping Han (Peking–Hankou) train for Luoyang in Henan Province. There, assuming you have secured a letter of introduction from a high-ranking member of Peking’s foreign community, you take the precaution of meeting with Field Marshal Wu Peifu at his headquarters, an enormous park four miles from the train station. Nicknamed “the Jade Marshal,” Wu is the much-feared warlord of the western region. The commander of a hundred thousand men, Wu is said to be the owner of the world’s largest diamond.

Ushered into your interview, you cannot help but be astonished by the portrait of George Washington wedged between the maps that cover the walls of the marshal’s headquarters. Unexpectedly, Wu is a small, birdlike man. His English, acquired at St. John’s University in Shanghai, is fluent. You accept his gracious offer to dine with him, hoping to sample the famed “swallow dish.”

The “Shui Xi,” the local “Water Banquet,” is served at several small tables, each set with six places. Outside, the military brass band is playing a medley of marches. The meal begins with eight cold dishes, and then sixteen warm dishes follow, each in a different-sized blue bowl, each cooked in a different broth. The pièce de résistance is, of course, the “swallow dish” of shredded turnip, which imitates a bird nest’s flavor. The banquet ends, the marshal rises, the dinner is over.

With emoluments to the marshal consisting of an assortment of presents, you now hope to have good guanxi—excellent connections—to ease your further travels. Next morning at six, armed with documents furthering your safe passage through the disturbed areas around the railhead, plus introductions to local officials and a cavalry escort provided by Wu, you leave the ancient walled city of Luoyang, now much reduced from its former glory as the capital. You set out in a rickshaw heading a dozen miles south to your destination—the caves of Longmen (Lung Mên), situated at the end of the legendary Silk Road, its grottos once the destination of streams of Buddhist pilgrims. Ferried over the Luo River on a raft, a pony awaits, and you ride to the tiny village guarding the caves of Longmen.

After Emperor Xiaowen (reigned 471–99 CE) of the Northern Wei dynasty moved his capital from Datong (Shanxi Province) to Luoyang in 495, it became the destination of Buddhist monks traveling along the trade routes collectively called “the Silk Road” between northern India, where Buddhism began, and China. Carved into Longmen’s dark gray limestone cliffs are 2,345 grottoes intended as hermitages for Buddhist monks. Once home to 100,000 sculptured images and nearly 2,500 stelae, the caves have lost their protective porticos and their outer halls have disappeared. One of the three largest cave complexes in China, the grottoes have long been abandoned for worship but are known and admired by the Chinese, particularly for their calligraphic inscriptions.

The first foreign explorer to visit Longmen was the Japanese scholar Kakuzo Okakura, who was later to head the Asian department of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Okakura stumbled upon the site half by accident in 1893, took some photographs, and returned home to Japan to lecture with his lantern slides of the Binyang (Pin-yang) cave’s central grotto. The French Sinologist Édouard Chavannes followed in 1907 and stayed for twelve days surveying, taking ink rubbings, and photographing. Charles Lang Freer, the American connoisseur of Asian art and principal donor to his eponymous museum, visited the caves in 1910. He camped for several days, commissioned photographs on glass negatives by the photographer Utai (now in the Freer archives), and remarked that the art seemed to surpass anything that he had seen before.

When he saw the photographs, Langdon Warner became smitten by two processional reliefs showing Empress Wenzhao and Emperor Xiaowen (the donors who paid for the statues of the Binyang cave). He forwarded them to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. “[Y]ou can see what classical Chinese sculpture was in its prime. Look at the procession of figures—it is as well composed as the Parthenon frieze, and for line I have never seen it beaten. . . . Sensei [Okakura] considers it very important that this mine of top notch Chinese sculpture should become accessible to the West—it is an unopened Parthenon or rather the whole Acropolis of Athens waiting to be studied.”

Photographs published by Chavannes in 1909 in his monumental work, Mission archéologique dans la Chine septentrionale, provided the impetus for the wholesale looting of the site between 1911 and 1949. As Duke’s Stanley Abe has written, the Frenchman’s scholarly volume “inadvertently provided photographic catalogs from which foreign buyers could chose works to pursue on the open market or in some cases ‘special order’—that is, indicate to their agents in China which pieces in situ they were interested in acquiring.”

Proof was provided by Langdon Warner. On his trip to Europe in 1913, he had dropped by the Musée Cernuschi. Installed in the private home of Henri Cernuschi, but bequeathed to the city of Paris by its owner, an Italian banker, it featured his renowned collection of Asian art. Reporting to his then mentor and employer, Charles Lang Freer, on the dozen sculptures in the museum that had recently been removed from Chinese caves, Warner noted that dealers in Europe were already marking photographs of Longmen for their agents in China, who were commissioning local stonecutters to steal the pieces to order. He worried that his own illustrated publications on China would have the same results, and “such a thing would be terribly on my conscience.”

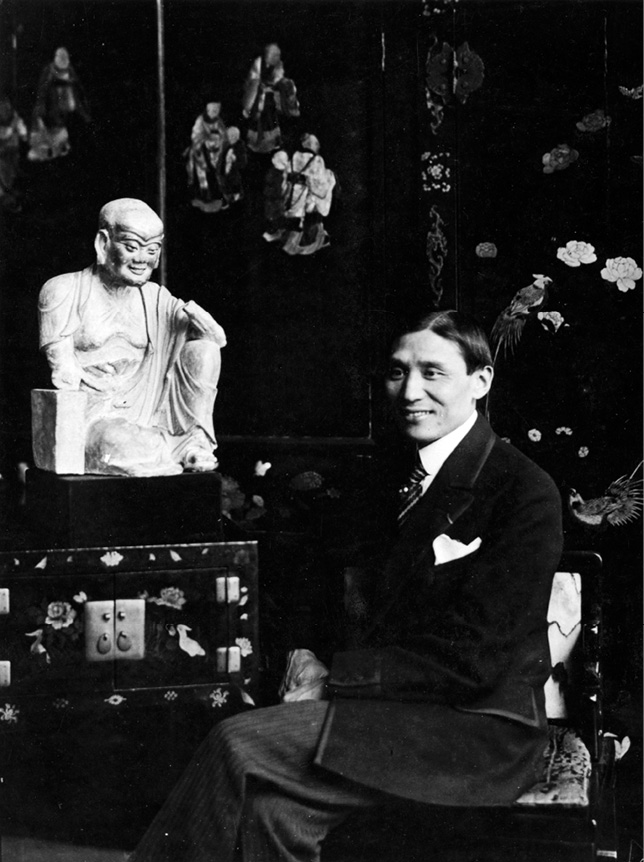

Enter Cheng-Tsai Loo, the foremost dealer in Longmen sculpture, who was to have a long and mutually profitable relationship with America’s curators and collectors of Asian art. In an interview with The Financial Times, Daisy Wang, the author of a dissertation on Loo, described his business model as “based on America’s capitalist and imperialist logic that Chinese antiquities were to be consumed by the rich and the powerful in modern America.” In that capacity, Loo served as “an exotic Chinese servant” for his Euro-American clientele. Now viewed by the Chinese as the chief culprit in the West’s plundering of Chinese art, Lu Huanwen (shortened by a French curator to C. T. Loo) was born in Lujiadou, an obscure silk-producing village, outside Huzhou in Zhejiang Province, to peasants—an opium-addicted father and a mother who later committed suicide. As detailed by his biographer Géraldine Lenain, Loo traveled to Paris as a cook on a boat arriving in 1902. There he went into business, partnering with the commercial attaché of the Chinese mission, Zhang Jingjiang, to found Ton-Ying & Company, which, besides trading in tea and silk, also dealt in Chinese antiquities. Their shrewdest investment was to use their profits, following the 1911 revolution that overthrew the Qing dynasty, to fund Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalists. They were able to use this leverage with the Kuomintang to export antiquities, many of them objects from the Qing imperial collections, despite the government’s restrictions, dating from 1913, on the export of antiquities.

The magna-dealer C. T. Loo amid his treasures.

Falling in love with a French milliner named Olga, who preferred to remain with her protector who had financed her business, Loo instead married her fifteen-year-old daughter and sired four girls. A ballroom dancer and a connoisseur of cuisine—he once owned a Chinese restaurant on the Left Bank—as well as of art, Loo began his career as a dealer with a small gallery in the Ninth Arrondissement on the rue Taitbout. Initially he found his inventory in Europe, but in 1911 he opened offices in Peking and Shanghai, which made it possible for him to obtain a number of important objects, many with an imperial provenance.

Early on, he sold ceramics to European collectors like Sir Percival David, whose remarkable collection is now housed in the British Museum, but as World War I raged in Europe, Loo broadened his horizons in order to sell to rich Americans like John D. Rockefeller Jr., Charles Lang Freer, Grenville Winthrop, Albert Pillsbury, and Eugene and Agnes Meyer. Just as China was abandoning Buddhism in its efforts to modernize, Americans like Isabella Stewart Gardner and Abby Rockefeller and her sister Lucy Aldrich were developing an interest in the religion. Loo thus found a clientele for his growing collection of Buddhist sculpture, and he shifted his focus to America, opening a gallery on Fifth Avenue in New York.

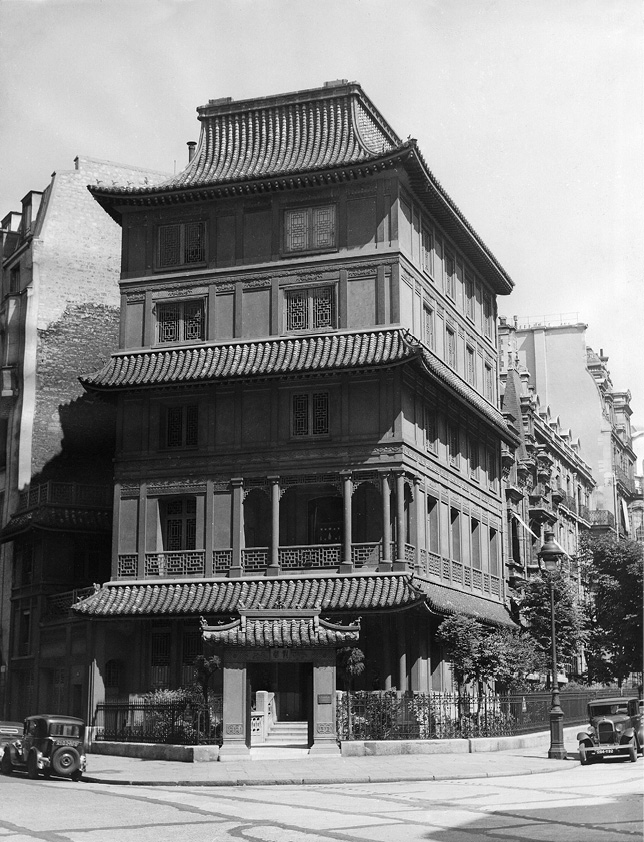

In 1926, he made an audacious move by renovating a nineteenth-century Parisian town house on the rue de Courcelles, turning it into a five-storied red Chinese pagoda lined with lacquer panels. It was conveniently located in the Eighth Arrondissement near the Musée Cernuschi and the Parc Monceau, the area of Paris that was becoming home to rich collectors. There, Loo “had the habit of not showing his best pieces to every visitor,” according to the German collector, Eduard von der Heydt. “Some of his Chinese pieces were hidden away in the cellar. He showed them only to those he believed to have real understanding for Chinese art.” Eventually, Loo became the most important dealer of Chinese art in the twentieth century. Dubbed by curator Laurence Sickman “the Duveen of Oriental art dealers,” Loo in time would become almost as controversial as Sir Joseph Duveen, the most famous peddler of European masterpieces.

Leading art historians researched and documented Loo’s finds; catalogues and exhibitions followed. In the preface to a 1940 catalogue, Loo recalled his initial engagement with Buddhist sculpture:

I remember one day in the spring of 1909, I called at the Musée Cernuschi in Paris to inquire for the director, Mr. d’Ardenne de Tizac, whom I did not know at the time. During our conversation he showed me a picture of a stone head and the fine stone immediately awakened in me a desire to develop a new line in Chinese Art. . . . I immediately mailed a photograph of the stone head to my partner in China and soon received word telling me that one of his buyers was traveling as interpreter in Sian for Mr. Marcel Bing, a French dealer. While they were talking to a local dealer, Mr. Bing kicked something hard under a table at which he was sitting. This was the head in which we had been interested and Mr. Bing, buying it for ten Chinese dollars, eventually sold it to the Stoclet Collection in Bruxelles.

Loo continues the story of his lucrative mail-order business: “A few months after this, I received a cable from my Peking office telling me that they had secured eight life-size stone statues. Not knowing how to dispose of these, I wired to get rid of them in China, but being unable to do so, they were finally shipped to me in Paris. Upon their arrival, I showed them to all the dealers, but no one wanted to buy. . . . Photographs were presented all over Europe but all in vain and so, in the winter of 1914–15, when I went to America, I took a set of photographs with me to show in this country.” And show them he did. Soon clients were checking off photographs, with results still on display in dozens of U.S. museums. Developing an elaborate network of buyers and scouts throughout the 1930s, Loo was able to purchase not only Buddhist sculpture but also entire collections of jades and bronzes from recently excavated tombs and wall paintings from ruined temples. It was his role in stimulating these activities that led him to be regarded as an arch villain by the Chinese. Where Loo led, others were soon to follow.

But we have gotten ahead of ourselves. Let us return to May 2, 1914, when a Times (London) editorial commenting on the flourishing market in Buddhist sculpture protested the “ruthless plundering and destruction of the noble monuments of Chinese art.” It detailed:

Colossal figures sculptured in relief, which illustrate in their own surroundings the wealth of Buddhist legend and theology, are mangled, sawn asunder or broken into pieces by clumsy thieves, in order that fragments may be taken to Peking and sold to European dealers. They are bought with eagerness by collectors, or by representatives of museums who would shrink from initiating the traffic, but argue that, as the spoil is already at their hands, it is their duty at least to provide it with a worthy resting place. Competition grows, prices rise, and the inducements to further ravage become continually stronger.

C. T. Loo’s Parisian pagoda-style gallery on rue de Courcelles.

Warner visited that same month but found there was no possibility of spending even one night. He had been warned by the city magistrate that there were a thousand robbers just beyond Longmen. “[T]roops rode out each night to have a brush with them and to keep things moving. . . . Two days before they had come to a pitched battle and more than a hundred robbers had been killed.” When he arrived, he saw the lopped-off heads of the robbers adorning the walls “each with its foul crow pecking and roosting through the bars of the cave in which it was hung up. There were corpses about, just beyond the walls, on which unnamable and unthinkable outrages had been done.” Mongol troops had been brought in, and they were quartered in the caves. “No stranger could stay on the spot, much less pursue the peaceful trade of archaeology.” But, as he wrote his wife, whom he had left behind in Kaifeng, “As a whole the place is beyond belief. In my opinion the group of ‘ladies’ which we know so well is the finest thing in Chinese art. Nothing I have ever seen can touch it. . . . As for the great platform where the seventy-five foot seated Buddha is with his eight attendants—well, that is one of the great places of the earth. . . . The damage that has been done lately is as bad as anything that we have heard—the fresh marks of broken heads both dug out for a purpose and knocked off by the soldiers are everywhere. . . . It was so bad that it made one almost physically sick.”

Back home, and engaged in cataloguing Freer’s burgeoning collection in Detroit, Warner noted that he was able to match one recently purchased head with the body left in Longmen, thanks to Freer’s photograph that showed the sculpture before the vandals beheaded it. Wartime conditions were already reducing the European demand for Chinese art, but the Americans with ready cash, predicted Warner, “will enjoy [an] unusual opportunity to buy things of rarity at considerably lower prices.”

When Warner returned to Longmen with Horace Jayne and their secretary-interpreter Wang in 1923, driven in a car provided by warlord Wu, he reported, “the chapels with their huge guardian statues sixty feet high at the portals were much as I remembered them ten years before, except for a few gaps in the sculpture where dealers had chopped figures from the solid rock or knocked off heads for our museums.” All such vandalism, Warner claimed, had been stopped, if only momentarily, under Marshal Wu. He lamented the government officials’ habit of making gifts of these treasures to foreign dignitaries and travelers.

Although the Chinese government enacted stronger laws, including that of June 7, 1930 (“Law on the Preservation of Ancient Objects”), and established governmental agencies such as the National Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities, the going was good for collectors and their “friends” at Longmen throughout the 1930s. According to Stanley Abe, ninety-six of the main caves were ransacked. Longmen sculptures, not all from Loo, are now scattered in museums from Osaka to Toronto, Zurich to Washington, D.C., and from San Francisco to Boston. Sculpture from Longmen continues to turn up at auction: Sotheby’s London knocked down a figure in 1993, and in April 1996, Christie’s Hong Kong offered a Guanyin head from Longmen, its provenance listed only as “an old European Collection.” The head was comparable to other examples, already known to be from Longmen, in the Los Angeles County Museum and San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum. Nothing, however, was as bold as the acquisition of two processional reliefs of the empress and emperor from the Central Binyang cave by two enterprising American curators: Laurence Sickman, buying in the early 1930s for a new museum, the Nelson Gallery in Kansas City, and Alan Priest, the Met’s long-serving mandarin of Asian art.

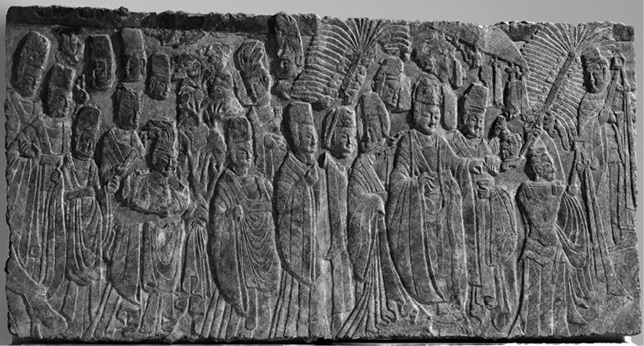

At the time of its completion in the sixth century, the twenty-five-by-twenty-foot Binyang cave was, as Sickman himself described it, both “lucid and coherent.” Against the back wall opposite the doorway sits the Buddha, attended by his disciples, and two standing bodhisattvas; on the sidewalls are trios—depictions of the Buddha with bodhisattvas. The front wall is divided into four horizontal registers, and there were two of the largest and undoubtedly most important items, the relief depicting the Dowager Empress Wenzhao and its companion frieze, where Emperor Xiaowen and his court were carved. Below are depictions of monsters; above are scenes from the Buddha’s previous lives. A scene at the uppermost level illustrates the Bodhisattva Vimalakı¯rti in a debate with the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, Mañjus´rı¯, a popular theme in China.

After the failure of the second Fogg expedition, Langdon Warner returned to China, having acquired, in addition to his teaching and curatorial duties in Cambridge, a lucrative sideline: advising the trustees of the yet-to-be-built Nelson Gallery in Kansas City. As someone who could collect Chinese antiquities on the spot, he recommended his prize student, Laurence Sickman, then in Peking studying on a Harvard-Yenching fellowship, to the Nelson’s trustees. At age seventeen, the Denver-born Sickman had developed a precocious interest in the Asian art that he encountered in the gallery of the Armenian rug dealers and Asian art specialists, the Sarkisians, near the Brown Palace Hotel. Midway through his University of Colorado years in the hopes of landing a museum job, he sought the advice of Alan Priest, who recommended transferring to Harvard “because the finest and most dependable single collection of Chinese and Japanese art is in the Boston Museum, and it is only by studying and handling actual objects that you will get any satisfaction out of your work.” There his talents were spotted by Denman Ross, who often invited him to his home to inspect his collection, and by Langdon Warner, whose course he took, and then confirmed by John Ferguson, who met and mentored Sickman in China, introducing him to private collectors and helping him gain entrance to off-limits sites.

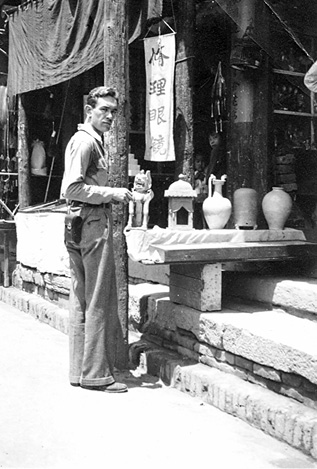

Laurence Sickman, still a budding curator in 1933, shopping in Luoyang, near the Longmen grottoes.

In 1931, while Sickman was in China on his fellowship, Warner broke him in. He accompanied the aspiring curator on visits to dealers in Peking’s antiques district, Liulichang, and to viewings of paintings in the collection of Henry Puji, China’s last emperor, in his temporary “palace” in Tianjin. On leaving China, Warner turned over to Sickman the five thousand dollars remaining from his Kansas City funds on deposit at the Chase Manhattan Bank. Initially working on a 10 percent commission and subsequently on a hundred-dollar-a-month retainer, Sickman was charged with acquiring “unusual objects of rare value.” As he recalled, “It was an opportunity heavily charged with responsibility, requiring more nerve and confidence than I really had at the time. As a beginner one can safely admire a painting or bronze exhibited in a museum and labeled, presumably, by an expert. The same work of art unlabeled, without provenance and in the market place can be another thing altogether.” It was the beginning of a collaboration that would see a vast Beaux Arts building, launched with an $11 million bequest from William Rockhill Nelson, proprietor of The Kansas City Star, become home to a world-class collection of Asian masterpieces, for the most part assembled by their soon-to-be curator and later director, Sickman.

Bantering letters full of gossip flew between Peking and Cambridge: “[My] Chinese is moving slowly but steadily,” Sickman wrote to Warner, “already I am able to get a glass of water out of the boy instead of a hammer.” Some detail the richness of the treasures: “liberated” objects from the provinces, and objects that the old aristocracy were obliged to dispose of, found their way to dealers, of which there were perhaps a dozen active in Shanghai and Peking. As Sickman explained in a 1982 interview, “All these people had permanent agents in the larger cities of the interior. These agents would be on the lookout constantly. It was a regular cloak-and-dagger business, of course. [There was] stiff competition among scouts, and then if a local official got hold of a certain number of things, he would know which dealers would be able to handle an object of that quality. These objects were never shown in [the dealers’] shops. They had runners that they would send to your house and they’d say, ‘Oh, we just got something I think you might be interested in.’”

Sickman credited the German dealer Dr. Otto Burchard with helping him fine-tune his “unerring eye, akin to perfect pitch.” A Heidelberg Ph.D., Burchard lived in Peking but had a gallery in Berlin, where in 1920 he was the first to exhibit Dada art. Burchard initiated Sickman in the art of tracking down important items that were not on display. According to Sickman, he would make the contact and say, “Come on now, let’s go down and see what this guy’s got. I saw it yesterday and I think it’s just what you need.” Once there, Burchard led him through the front room, “full of porcelains and jade and knick-knacks, and then two or three rooms behind would be the inner sanctum of the dealer where you would go and be shown the important works.” Sickman reflected, “Unless you had pretty close contact with the dealers, you wouldn’t get anywhere.” Occasionally, Burchard would buy an object and hold it for Sickman until photos were sent for the necessary approval, often withheld, from Warner, who was known not to have a very good “eye,” particularly in regard to Chinese painting.

But Sickman proved a fast learner. One anecdote, related by the China hand Owen Lattimore, suffices: “He had a dealer in this morning who wouldn’t come down to his price. Then the Japanese sent over an aeroplane and that fixed it; Larry excused himself to the dealer saying that he was very busy as he had a lot of packing to do in the case of having to move—in the meantime looking apprehensively to the sky—and the dealer revised his price.”

Another important figure in Sickman’s life was the Methodist missionary John Calvin Ferguson, connoisseur and advisor to the newly opened Palace Museum, whose network included many warlords and officials eager to sell off major collections. Ferguson wrote admiringly of Sickman’s intelligence and diligence, his readiness to follow up on the older scholar’s suggestions for Chinese books to study, and his “wonderful charm of manner.” During his four-year stay in China, Sickman walked over and photographed much of northern China, tracking down village temples and pursuing his scholarly interest in Buddhist art, often for six weeks at a time, accompanied by Hui-jung, his trusted assistant (who was later kidnapped and executed by the Japanese).

Sickman’s friends, including the memoirist George Kates (The Years That Were Fat) and Oxford’s bird of paradise Harold Acton (immortalized in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited as Anthony Blanche), the author of Memoirs of an Aesthete, have described Peking’s exotic international community in the 1930s. Acton, who developed a lifelong friendship with Sickman in Peking, and parts of whose Chinese collection remain in the Kansas collection, summed up his youthful colleague as a connoisseur of all things Chinese:

Some of the most splendid moments of the day were when Laurence walked in with some treasure he had discovered, and he was constantly discovering treasures, from Chou bronzes to jade cicadas, for the fantastically fortunate Kansas City Museum. I marveled at his integrity. Anybody else with so personal a passion for these things, would have appropriated them for himself, and how could Kansas City be any the wiser? In his hands they glowed like sleeping princesses at the wakening touch of a Prince Charming, and he led them as brides to the altar of his charming house in the Hsieh Ho Hutung. I was often privileged to be the best man at these nuptials. But after a brief honeymoon, they were sent to sleep again behind the glass cases of the gallery in Missouri.

The long, unhappy story of Kansas City’s renowned The Empress with Donors frieze (see color plates, figure 5) is told in a series of letters between Langdon Warner and Sickman that have slept undisturbed in Warner’s Harvard and Sickman’s Kansas City archives. When Sickman first appeared at Longmen in the fall of 1931, the two friezes, measuring in width nine feet (the empress) by nearly thirteen feet (the emperor) in the Central Binyang cave, were still intact. Sickman spent a week there, commissioned ink rubbings of the friezes, and took copious notes. In late 1932, he began to see Longmen fragments in the shops of Peking dealers: “single hands, bits of heads, fragments of low relief decoration from niches and inscriptions.”

In December, he approached T. L. Yuan (Yuan Tongli), the director of the National Library in Peking and member of the Commission for the Protection of Antiquities: “I told him of the conditions and urged him to do what was within his power to preserve the caves. His reply was that this destruction would not go on unless sculpture fragments were purchased by foreigners. My reply to this was, in effect, that so far as I knew no foreigner had attempted to purchase any sculpture fragments or pieces . . . unless they appeared on the Peking market and that it was useless to attempt to control the traffic from that end, while on the other hand it would be very simple to stop any pillaging at the caves. At this time, I offered to raise funds from foreigners interested in Chinese art to station a number of police at the caves. Mr. Yuan said no such assistance was necessary.” A further letter from Yuan asked, “Would it be too much trouble to you to find out the names of the stores which keep the sculptures from Lungmen? The authorities are taking steps to stop the ruthless destruction at the source and I am particularly grateful to you for having informed me about it.” Sickman refused to name the dealers. (Yuan would become a pioneer in the tracing and documenting of Chinese art in American collections.)

Revisiting the caves in March 1933, accompanied by a local official and the Harvard scholars Wilma and John King Fairbank, Sickman recalled, “In many of the earliest caves those from the years 500 to 525, heads of images had disappeared and in places whole figures had been chipped from the walls and niches. A large section of the empress relief and several isolated heads were gone.”

At the end of January 1934, Sickman reported to Warner that Burchard had purchased the two female heads that had been missing from the friezes in 1933: “We then began to hear of more and more pieces of the frieze being on the market. . . . After talking the matter over carefully with Dr. Burchard, we decided to attempt to assemble as many of the fragments as we could. Our motive was to secure this best example of Wei sculpture and to preserve it as nearly intact as possible. It was too late to report the matter to the authorities. The damage had been done. . . . It was obvious that regardless of what remained at Lung Men, the value of the relief in situ had been lost [and] to gather what we could of it then, and restore it carefully with the funds which we had at our disposal, seemed to be the greatest service we could render.”

In February 1934, Kansas City informed Sickman that it had all the sculpture it wanted for the time being. He inquired of Warner, “What are we to do? Of course the entire matter is very secret here.” In despair, he writes, “Lung Men is being completely destroyed. It may be that I am fortunate in being on the spot at the time. The caves have lasted since the sixth century. In a year they are lost. This is one year out of one- thousand-four-hundred. Now the shops are full of Lung Men stones, in a few years they will be as rare and valuable as Attic Greek.”

At this point it seems that a plan evolved at the instigation of Warner, but approved by Forbes, that the Fogg and the Nelson would jointly purchase the frieze, and since most of it was in small pieces, Burchard would assemble it. By April, Sickman had succeeded in acquiring most of the frieze, for which the initial down payment was to be $13,000. On April 25, Forbes telegraphed Paul Gardner, director of the Nelson: “am mailing you six thousand dollars stop can supply extra five hundred after july first.” In May 1934, two large restored sections were due to be shipped in three cases. For this he needed the help of Jim Plumer, then working for Chinese customs, to avoid close scrutiny in Peking’s port, Tientsin. Instead he shipped it via Shanghai. Sickman details the yearlong saga of the “Chinese puzzle,” in a letter that Plumer was asked to destroy after reading:

I was then a happy artless young man, I am now gray and bent, and my mind none too clear, but I have the complete relief of the entire procession. From here and there, from shop after shop, from K’ai Feng, from Cheng Chou, yes, from Shanghai, I have collected bit by bit, half a head here, a sleeve there, a hand from Hsia, hundreds and hundreds of small fragments. . . . But at last the greatest single piece of Early Chinese sculpture has been assembled, and I feel that we have done something for the art of China and for the world the value of which can only be estimated in future generations. Three months to put it together. Little boys sit all day long trying this piece and that. Where does it go, how does it fit? Is it an eye or a bit of ruffle?

Nevertheless, by the end of May, he was able to write to Warner, “[T]hree large cases have gone and it was a difficult task. I already feel three years younger.”

Yet on his next visit to the caves in June, Sickman was shocked to find he had far less of the frieze than he had thought. Worse yet, he worried that he had bought some forgeries, which were starting to appear: “Certainly all the heads are original and some of the drapery, other parts of the drapery may still be in Peking and some of the drapery which we have is not in proper order. The difficulty is that one can not send men there to get what is left. . . . It is, in short, something of a mess and I am in the very depths of depression about it.” Burchard at the time was in Germany, winding down his Berlin gallery, but as he wrote to his friend Sickman, “I feel so deeply sorry for all the clouds and your sleepless nights and for all the troubles. . . . But be sure I shall repair it all until the last missing pieces will be in your hands. . . . A short while before we left China, I sent the ‘original’ people from the place to whom I made quite good offers for all the rest still on its place. I made a firm contract and they have sworn to deliver at least the greatest part of it. . . . When I missed and failed in buying a forged drapery so I have only one consolation that even a better expert like [sic] me would probably have fallen a victim when acquiring all the small fragments.”

Rumors of the demolition of the Empress frieze had reached New York, however, and a rival for the remaining spoils in the guise of the Met curator Alan Priest would arrive in the summer of 1935.

We last left Priest in 1925, on the way back from Dunhuang with Horace Jayne and the Fogg’s second expedition. The next year found him on a Sachs fellowship in Peking, scouting antiquities for the Fogg and writing to Sachs that he was living in a “perfect love of a Chinese house. . . . I have a cook and a ricsha [sic] boy and a white dog and a young Chinese scholar who speaks no English and I am probably the happiest person that you have ever been acquainted with. Mornings an old scholar comes to read Mencius for three hours and evenings a young one comes to read newspapers or art or just gossip. . . . Week ends I visit temples in the city or go over to the Western Hills.”

Priest’s fellowship allowed him (between rounds of antique shops in Liulichang) to study the language and to pursue his particular interest: Chinese theater. He learned entire plays and entertained his foreign friends and Chinese guests from the Society for Classical Drama with scenes screeched steadily for half an hour in his creaky falsetto. His thespian efforts impressed the Chinese and were the subject of three articles in a Chinese paper, ending with the journalist’s tribute: “For the first time have I seen East and West truly happy together in one room, the people of the Middle Kingdom and the people of the outer countries merry together! Who does not believe this? Let him challenge me with his brush! I would defy and smite him!”

Emperor Xiaowen and His Court, ca. 522–23, Alan Priest’s consolation prize.

At home in Peking, he was attended by his coterie of nubile houseboys, whom he dressed in Chinese scholar robes, giving rise, as Priest whined to Sachs, to “town gossip to the effect that it is such a pity that that bright young man has ‘gone native’ and that ‘he has orgies of Chinese actors and their concubines.’” But according to his colleague, the Freer Gallery’s Carl Bishop, Priest had become “so thoroughly Sinicized, even to the extent of clothes, food, dirt floors, and the immature offspring of Pekinese poodles running around micturating over everything, that things must have taken a decided turn for the worse, even to pry him loose from those regions.”

(Priest identified so strongly with the Chinese during his Peking sojourn that he became a Buddhist abbot and arranged to be buried in China in a Buddhist cemetery. However, World War II and Communist politics intervened, and he was forbidden a Chinese burial. He died in Japan, in quarters provided by the family of Japanese dealers Yamanaka in Kyoto, where he is buried.)

In 1927, Priest was offered the position of acting curator at the Metropolitan Museum as successor to Sigisbert Chrétien Bosch Reitz, who had returned home to the Netherlands. Depending upon your social or working proximity to the flamboyant Priest, he was “witty, urbane and scholarly” or “a crusty, malicious character modeled on the then-popular image of the lovable rogue who insults everybody (see The Man Who Came to Dinner: etc.) and played the part well.”

In accepting the Met’s offer, Priest stressed his hard-won preparation for the position:

But this I know (and it is no vain boast) that every minute I have spent jogging along desert roads in a cart (and consciously thinking only would the boy have eggplant for dinner) and every minute I have spent in the little alleys, the theater, parks, tea-houses and homes of the Chinese has given me the means to greater understanding and sympathy with this great people and gives me a better right to say this painting is Sung, this stone is Wei. I love them—sometimes I could kill them all but still I love them and would like engraved in letters ten feet high on my tombstone “There have been two greatest of peoples, the Greeks and the Chinese.”

Bosch Reitz had made do with one forlorn assistant and few funds, but successive curators have lauded his successes, including a large gilt-bronze Northern Wei Buddha and a collection of paintings bought on Charles Freer’s recommendation from John Ferguson. The Met’s collection was strong in porcelains from the Altman collection and bronzes purchased, again with Ferguson’s intercession, from the family of the deceased Chinese connoisseur and collector, Viceroy Duanfang. However, these items were definitely not central to Priest’s taste, “because beautiful as the bronzes and porcelains are, they do not seem to me comparable to what I think of as the major arts, painting and sculpture and architecture.” He vowed “to develop a collection appropriate to the size of this Museum and of the city. . . . We need to emphasize objects which are both large in size and great in execution.” A frieze from the Longmen would fulfill both requirements.

Morality was bent in 1934 when, flicking ashes from his omnipresent cigarette holder, Priest returned to China in search of Longmen stones. He had written to the Metropolitan’s director Herbert Winlock that “the great reliefs of Lung Mên (comparable in Chinese art to the Parthenon or Chartres) are being broken up and that some of the frescoes of Tün Huang (the greatest of China’s wall paintings) are scheduled to appear in Peking. I should be there and have every scrap of information about them for the museum, whether we can secure them or not.” Once he had arrived, he heard, via the Peking gossip mill, that he had a rival in the person of Larry Sickman.

A friend of Priest’s who dealt in Longmen sculpture, Yue Bin, confided to him that Otto Burchard had the Empress frieze. Priest then reported to Winlock that Burchard was “carrying on some kind of cabal with old father Ferguson, dear little Sickman, Langdon Warner and Kansas City. However there is more and we can have some of it if we want it.” When Priest questioned Sickman, the latter was put “in a rather awkward position” as Priest was “furious about it as he had hoped to arrive in time to get it.” As the final arrangements had not been concluded and the cases had not been shipped, Sickman told Priest as little as possible, treating it as a confidential museum matter that he was not at liberty to discuss.

But the Emperor procession was still up for grabs. In the autumn of 1934, Priest contacted Yue Bin and agreed to pay the dealer $4,000 for six heads of the group that Yue already possessed. The others still on the site were to be hacked from the walls by bandits under contract to Yue’s agents. When he obtained another thirteen heads, Yue would get $10,000. The contract with Yue’s shop, Pin Chi, would be void “if things occurred at the mountain” and if “conditions no longer obtained.” As Amy McNair has noted in her detailed study of the site, Donors of Longmen, “This strongly suggests the other pieces had not been stolen.”

Hungry villagers cut away the relief, bribed the local military, and loaded sacks, which were delivered to the Baoding prefecture. After they were assembled in Peking, a local agent, storeowner Nellie Hussey, provided a fraudulent bill of lading to deceive custom officials, and then shipped the stones to New York. In spite of the agreement, Priest still had difficulty in obtaining “twenty-one key pieces,” probably including the missing heads. When he wrote an article about Longmen in 1944, he feigned shock at the dismantling of the site and announced correctly that many of the items in the marketplace were fakes: “This was the way the things were raped: the little village near Lung Mên stands watch, but from across the river men waded armpit-deep and chipped fragments from the surface at night. These they took down to Chêngchow, where agents of the Peking dealers bought them. In Peking the fragments were assembled, and with zeal copies were made from photographs and rubbings. You will find heads purporting to be the original heads of the male and female donors of Lung Mên scattered broadcast through Europe, England, and Japan, and they are mostly complete forgeries.” Nevertheless, the Emperor frieze, when assembled by the Met’s minions, retains pride of place in the main Asian gallery.

In a coda to the story, in 1940 the Fogg and the Nelson agreed, in light of the weight and fragility of the Empress frieze, that it should not be separated, nor should it be shipped back and forth to be exhibited alternatively in each museum every few years. Forbes then accepted the Nelson’s counterproposal that the money advanced by the Fogg for the purchase price would be refunded and that the Empress, for which the total bill was $32,000, would remain in Kansas City.

Stealing to order by dealers continued throughout the 1930s, and the efforts to protect the sites frequently failed. One anecdote suffices: Dr. George Crofts, who was initially responsible for Chinese collection at the Royal Ontario Museum, was offered a head from Longmen by a dealer. Thinking that it was a shame that the head had been taken from China, Crofts bought it and gave it back to the Chinese government. But the second time that this same head was offered to him, he bought and kept it.

As demand outstripped supply, these fakes proliferated and greatly complicated provenance research. At the Metropolitan Museum, Priest continued to acquire pieces of Longmen stone sculpture, of which some are now considered questionable. As for the Nelson-Atkins Museum, when Chinese officials attended the opening of the 1975 exhibition “Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China,” as a nod to the sensitivity of Chinese feelings in the matter, it was decided to erect a temporary wall in front of The Empress with Donors.

The Chinese author Gong Dazhong relates that when the Communists came to power in 1949, parts of the Emperor Procession were found at Yue Bin’s Peking house. They were reassembled, minus the heads. After the exposure of the crime, more than three hundred people representing the cultural elite of China petitioned the government to punish Yue. He died in prison in 1959. During the Cultural Revolution, the site remained relatively untouched. Protection increased when after the destruction of a local Buddhist monastery, the municipal party committee secretary ordered teachers and students at the Luoyang Agricultural Machinery Academy to provide the site with around-the-clock protection. Declared a protected cultural property in 2000, Longmen was placed on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage sites and granted over a million dollars toward restoration.

The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 also brought an end to lucrative art dealing on the mainland. Loo announced his retirement the following year. In a letter to his clients he announced: “I am seventy years old now, and since half a century I have been collecting and selling Chinese antique works of art. A very interesting profession which has combined business with pleasure: rarely a day has gone by without some excitement of securing or planning to secure certain objects. The definite confiscation by the new authorities in power at Shanghai of a large collection containing a great number of very important objects, has made me suddenly realize that dealing in Chinese antiques is at its end, and that I would be deprived of all my enjoyment.”

As for the ravaging of Longmen, these statements by the principals provide an instructive postscript:

[China’s] National Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities (1931): “The export of archaeological objects from their country of origin can only be justified when (a) the objects are obtained legally from their rightful owners, (b) the taking away of any part of a collection will not damage the collection as a whole, or (c) there is no one in the country of their origin sufficiently competent or interested in studying or safe-keeping them. Otherwise it is no longer scientific archaeology, but commercial vandalism.”

Edward Forbes to Paul Gardner (1934): “I think it is an outrage that the Chinese government should have allowed these great sculptures to be hacked off the walls of the cave and to leave the country. But I think as we had nothing to do with hacking them off the walls of the cave and first heard of them when the mutilated pieces were in Peking being put together, we are justified in buying them for posterity in this way even if to accomplish the object of preserving them we have to divide the sculpture into two halves, one for each museum.

“I feel strongly, however, that we are preserving these for the benefit of the human race and that as they really belong in China, if at any time in the future China becomes sufficiently stable and well organized to enable the Chinese government to preserve such objects with safety for the benefit of the human race, it would be a very handsome and proper gesture for the Fogg Museum and the Kansas City Museum to sell these objects back again to the Chinese government.”

Langdon Warner (1940): “If we are ever criticized for buying those chips, the love and the labor and the dollars spent on assembling them should silence all criticism. That in itself is a service to the cause of China bigger than anyone else in this country has ever made.”

Loo (1940): “I feel so ashamed to have been one of the sources by which these national treasures have been dispersed. . . . China has lost its treasures but our only consolation is, as Art has no frontiers, these sculptures going forth into the world, admired by scholars as well as the public, may do more good for China than any living Ambassador. Through the Arts, China is probably best known to the outside world. Our monuments may be preserved even better in other countries than in China, because of constant changes and upheavals and so our lost treasures will be the real messengers to make the world realize our ancient civilization, and culture thus serving to create a love and better understanding of China and the Chinese people.”

Priest (1941): “It has been said that one of the chief functions of a museum is to preserve the monuments of the past and keep them for a more temperate future—that five hundred years from now museums will be said to have played the role in our day that the monasteries played in the Dark Ages when the Roman Empire broke up. . . . The museum can’t give you the whole glory of Lung Mên, but it has caught a fragment for you.”

Priest again (1944): “These two reliefs, the male and female donors of the Pin Yang Tung, are a lost thing—nothing more wicked has ever happened to a great monument of a race. They are gone—we have only pathetic fragments to show.”

Sickman (1967): “The work is rather like a person who has suffered a very severe accident. The skill of the facial surgeon may make him recognizable to his friends but he is never quite the same. . . . All who are concerned with the cultural traditions of China would far rather wish that the relief of the empress were still in far off Ho-nan province, an integral part of the Pin-yang cave for which it was made.”

Finally, Sickman again (1981): “ . . . the whole project was financed as a salvage operation by Edward Forbes at the instigation of Langdon Warner, and it was only eventually that the Gallery bought the project from Mr. Forbes. As for myself, I would give almost anything if it had never left the Pin-yang cave.”