What the Internet is to our era, railroads were to the Gilded Age. In both cases, a mega-innovation circled the globe and in unforeseen ways affected everyday life, national priorities and policies, and even the market for fine arts. In the United States, as the historian Stephen Ambrose reminds us, next to winning the Civil War and abolishing slavery, completing the world’s first transcontinental railroad “was the greatest achievement of the American people in the nineteenth century.” This colossal feat of engineering, for which ground was broken in 1863, in the very midst of the Civil War, was the collective work of risk-taking financiers, war-seasoned veterans used to giving or taking orders, and, crucially, some fourteen thousand job-hungry Chinese migrants who constituted two-thirds of the work force. “After all,” one of the financiers is said to have remarked, “they knew how to build the Great Wall.”

Viewed globally, the Iron Horse unsettled the established calculus of military strategy, starting with the North’s decisive employment of steam and steel during the Civil War. In a remote, very different arena, the young Lord Curzon in 1888 became the first Englishman to book passage on Russia’s just-completed Trans-Caspian Railroad. The soon-to-be viceroy of India instantly grasped its sobering military implications, that is, that masses of tsarist troops could move swiftly by rail rather than lumbering horsepower to distant and contested frontiers, thereby complicating Britain’s ability to defend India. A few years later, Russia completed the Trans-Siberian Railway, the earth’s longest continuous railway (5,338 miles), built with the essential sweat and muscle of as many as 200,000 Chinese laborers. When Curzon elaborated the strategic implications of all this in a lecture at Newcastle, his onetime Oxford classmate, the geographer Halford J. Mackinder, was mesmerized and soon became the gloomy founding prophet of a new approach to reckoning strategic risks: geopolitics.

As unpredictably, the Locomotive God helped inflate the Oriental porcelain bubble in Western art markets. World grain prices slumped as American wheat from prairie states began flooding global markets in the 1880s, consequently shaving the income of Britain’s landed aristocracy, thereby precipitating the sale at auction of inherited artworks, notably including Chinese porcelains.

Yet there was another improbable by-product of the railway revolution: the nurturing of a new breed of affluent American collectors with a passion for Asian antiquities—which, in turn, was linked to the spread of railways in Imperial China, its soil laden with noble tombs that workmen accidentally, or deliberately, unearthed. Leading the way were Baltimore’s railroad moguls William and Henry Walters, who in 1886 made headlines by bidding an eye-widening $18,000 at a New York auction for a Chinese “peach-bloom vase.”

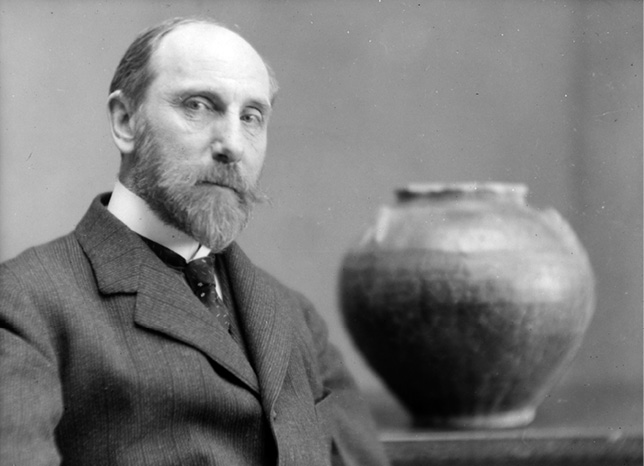

Charles Lang Freer, wary and ruminative, next to one of his favored Asian progenies.

There is no more compelling example of this new breed than Charles Lang Freer. Self-made and self-taught, Freer earned a fortune as a railroad-car manufacturer, much of which he spent on his travels to Japan and China while gathering a world-class art collection; at the same time, he won approval for establishing in Washington the first federally funded art museum, the essential precedent for seeding the National Mall with six kindred galleries. Finally and not least, he pressed creditably, if vainly, for the sensible road not taken to safeguard China’s imperiled antiquities. Yet this improbable industrial magnate fit into no readily defined niche. He was reclusive, fastidious, idiosyncratic, lean in frame, with an immaculately groomed Vandyke beard. As characterized by the art critic Aline B. Saarinen, he was a loner who “isolated himself in a silk cocoon against the showy, boisterous pageantry of his age.” Even in the competitive jungle of Detroit, Freer nurtured “a private world of refinement and serenity and excellences.” An impenitent bachelor, he sought out strong-willed and unconventional aesthetes like the Museum of Fine Arts savant Ernest Fenollosa, as well as America’s crankiest, antimaterialist rebel, James McNeill Whistler (thereby gathering the most complete selection of the artist’s works, including his Peacock Room, adorned with the obligatory blue-and-white china).

Nevertheless and incongruously, it was Freer’s materialist acumen that enabled him to semiretire in 1900 as a multimillionaire at age forty-four. As improbably, a few years later this maverick art lover somehow persuaded the culturally challenged masters of Washington to approve an unprecedented citadel for his exotic progeny. He earned an epitaph like that bestowed on Sir Christopher Wren, inscribed in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral: “If you seek his monument, just look around.”

Born in Kingston, New York, in 1856, Charles Lang Freer was the descendant of Huguenots who fled France to escape religious persecution and, like many dissident believers, found welcoming asylum in the Hudson Valley. The son of a ne’er-do-well breeder and trainer of horses, Charles left school at fourteen and worked first at a neighboring cement factory, then as a bookkeeper in the town’s general store. There he was hired by the newborn Kingston & Syracuse Railroad, which had its offices in the same building. Freer so excelled as the local paymaster that he became the star protégé of his superior, Frank J. Hecker, joining him when they moved on to Detroit. There they both climbed the management ladder at Peninsular Car Works, a company that, after complex mergers involving a dozen other firms, mutated into the American Car & Foundry Company, soon to become the country’s plenary manufacturer of railroad cars.

Charlie Freer excelled as both a diligent treasurer and a hard-driving vice president. Yet as a rising Detroit executive in the 1880s, he did not accord with conventional norms. While Colonel Hecker (as he dubbed himself after serving briefly in the Spanish-American War) built a gaudy mansion resembling a turreted French château, his junior partner chose understatement on an adjoining lot. Built of purplish brownstone from his native Kingston, Freer’s shingle-style residence featured informal built-in seating and open-plan spaciousness, as designed by Wilson Eyre, a contemporary-minded Philadelphia architect. Here, amid woodwork richly lacquered under his personal direction, Freer entertained select friends among Detroit’s cognoscenti, dispensing anecdotes about the East Coast art world he had begun exploring. During the 1890s, he not only traveled regularly to Europe, where he met Whistler (turning up unannounced at his Chelsea home in London), but also bought a villa in Capri, a sanctuary for his like-minded aesthetic friends. There he befriended the artist Romaine Brooks, known for her androgynous portraits of women, and along with his male companions, Freer explored the Grotta di Matromania, where they joined in chanting verses by Omar Khayyam.

By then, Freer was incurably infected with the collector’s bacillus. During his trips to New York, he began purchasing contemporary European and American etchings and drawings, until his eye was caught by Japanese prints at a Grolier Club exhibition in 1889, the first of its kind in America. His Asian interests were broadened by Fenollosa, recently arrived as curator at Boston’s MFA, to whom he regularly paid $200 or more for his “services as an expert” in advising on potential purchases. Freer also diligently sought the counsel of other artists and scholars whom he cultivated in Manhattan. In 1889, having visited the New York studio of Dwight B. Tryon, Freer purchased off the easel his first painting, a misty landscape by that artist depicting a haystack shimmering in moonlight, its style much in the Whistler mode. Over time, Freer’s choice holdings of American art came to include paintings or sculptures by Winslow Homer, Albert Pinkham Ryder, John Singer Sargent, and Abbot Henderson Thayer, all well-regarded today.

In his successive European trips, Freer resourcefully explored the new frontiers in the visual arts; he dined in Paris with the American painter Mary Cassatt, sought out the sculptor Auguste Rodin in his studio, and received a highly unusual request from his spiritually close friend, James McNeill Whistler, whose wife, Beatrix, was stricken with cancer. She was a devoted bird lover, and since Freer in 1895 was en route to India on his first Asian trip, Whistler asked if he could somehow acquire for her a particular blue and gold songbird. Freer volunteered, and on reaching Calcutta he bought a living specimen and then persuaded a British sea captain to care for it on his return voyage and to convey it personally to the artist. Against the odds, the plan succeeded. The Indian songbird joined a white parrot and a mockingbird in the cage at the Whistlers’ Left Bank home at 110 rue du Bac. On March 24, 1897, shortly following his wife’s death, the grieving artist wrote to Freer: “Shall I begin by saying to you, my dear Freer, that your little ‘Blue and Gold Girl’ is doing her best to look lovely for you?” During his wife’s final hours, Whistler related, “the strange wild dainty creature stood up, and sang and sang, as it had never sung before—a song of the Sun!—and of joy!—and of my despair! Peal after peal, until it became a marvel [that] the tiny beast, torn by such glorious voice, should live!”

As a collector in the 1890s, Freer was drawn to the Far East, initially to Japanese art and then to the less well-known paintings and sculptures of the ancient Middle Kingdom. Still, it was not aesthetics alone that guided his purchases. He was by nature a calculating bargainer, and there were few better deals in his prime buying years than Asian art. Freer made four trips to East Asia, in 1895, 1907, 1909, and 1910–11. It was his practice everywhere to seek and inspect both private and public collections as his buying swelled from retail to wholesale. As John A. Pope, a former director of the Freer Art Gallery, justly remarks, “Entries in his diaries and statements from his correspondence from these years reveal how much Mr. Freer learned during these trips, and how modest he was about his own knowledge, even after he was acknowledged as an important collector.” It helped that Freer’s Far Eastern travels coincided with the literally earth-moving impact of the locomotive on the troubled final decades of the Qing dynasty.

China was a relative latecomer to the railroad revolution, principally owing to a deadlocked debate within the imperial household between reformers and traditionalists during the 1880s. Opponents claimed that laying rails would make China even more dependent on foreign powers, whose rivalry had already carved much of the realm into privileged enclaves. Moreover, writes the Chinese historian Cheng Lin, conservatives feared that railroads, by disturbing ancestral graves, “would facilitate the spreading of ideas and influences subversive to the religion and morality of the Chinese people. The evil influence of railroads was even compared with the devastation wrought by floods and wild beasts.” For their part, reformers stressed “the advantages of the railway in the transportation of grain, famine relief, trade, mining, collection of taxes, and traveling. Above all, for military reasons, the building of railways should begin without delay.”

Following China’s ignominious defeat by Japan in 1894–95, it was the military argument that prevailed. In Cheng’s careful calculation, in the seven years from 1897 to 1904 “more railway projects were initiated and loan contracts signed than during the whole of the preceding half-century.” Thus by 1898, British concessions totaled 2,800 miles, followed by Russia’s 1,530 miles, with Germany and Belgium sharing third place (700-plus miles each), while France and the United States lagged far behind (420 and 300 miles, respectively). This carving up took place, writes Cheng, an advisor to the railroad ministry in the 1920s, without the consent or even the knowledge of the central government. He adds a widely shared Chinese judgment: “The sporadic attacks upon foreign residents in different parts of the Empire during those years must be regarded as demonstrations of popular indignation, and the anti-foreign movement spread until it culminated in the Boxer Movement of 1900, an incident for which the Powers, in their mad struggle for railway concessions, must bear the major part of the responsibility.”

The railway upheaval, and its side effects, played a catalytic role in Freer’s discovery and connoisseurship of Chinese art. As steel rails wove through the empire, an inescapable by-product was the discovery by workers of richly furnished dynastic tombs, sending streams of high-quality works into an awakening art market. Moreover, the lines enabled Freer to travel through China to study new offerings and to consult two valued advisors, the collector-politician Duanfang in Tientsin and the missionary-turned–art expert John Calvin Ferguson in Peking.

Ferguson was arguably more learned in China’s ways and classical canon than any contemporary Westerner. He lived in China for fifty-five productive years, dating from his arrival in 1887 at age twenty-one until his departure in 1943 as a Japanese detainee aboard the Swedish-American liner Gripsholm in a wartime prisoner exchange. Born in Canada, Ferguson was an ordained Methodist minister who earned his doctorate in divinity at Boston University. He was sent to China by his church to establish Nanking University, and having done so began a fresh career as the owner of a Shanghai newspaper and as an enabler for foreign enterprises and art collectors.

What set Ferguson apart, as Warren Cohen writes in East Asian Art and American Culture (1992), was his conviction, uncommon among missionaries, “that he could learn as well as teach in China, that Chinese culture was worth studying.” He sought not only students for his new university but scholar-officials who could teach him. Ferguson translated mathematics and chemistry textbooks into Chinese, “but also became so knowledgeable about Chinese art and art criticism that he was able to write books on these subjects that are still used by American authorities.”

These were attainments not then readily appreciated by American connoisseurs of Oriental art, many of whom viewed the very different genres of Chinese art with Fenollosa’s formalistic, Japan-slanted aesthetic. Hence in 1913, when Ferguson, as commissioned, shipped a choice selection of Chinese artworks to the Metropolitan Museum, its staff expressed disappointment. Most especially, the Met rejected a Chinese painting for which its departmental curator said he would not pay ten dollars: Nymph of the Luo River, attributed to Gu Kaizhi and now believed to be a Southern Song copy of a fifth-century work. Fortunately, Freer differed. He eventually acquired the Nymph as well as other Ferguson offerings found wanting by the New York museum. The disputed scroll is now deemed the single finest Chinese painting in the Freer Gallery collection.

A bachelor without direct heirs, Freer realized early in the new century that his art collection would be his enduring testament. Why not offer it as a gift to the American people? What better place than the nation’s capital, at that time shamefully behind London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna in paying homage to the arts? With that goal in mind, Freer in 1904 visited Washington to sound out Samuel P. Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, who expressed interest and noted that Congress had in theory approved creating a “National Museum of Art,” but only in amorphous principle. In 1905, Freer formally offered his treasures to the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents. Freer’s proposed gift, numbering around two thousand works, consisted of three parts: antiquities he acquired in the Near East (principally in Egypt); various American works, mostly by Whistler, whose reputation had begun to soar; and Asian paintings, porcelains, and statuary, all of which were (in his view) “harmonious in spiritual suggestion, having the power to broaden aesthetic culture, and the grace to elevate the human mind.” His conditions were firm: he would keep adding to his gift and help finance the museum’s construction, but none of his works were to be sold or loaned elsewhere.

Washington then had no internationally recognized art museums. Nicknamed “the nation’s attic,” the Smithsonian galleries were filled with scientific inventions, natural history specimens, ethnographic and historical memorabilia, salted with a sprinkling of artworks. In addition, the privately endowed, half-century-old Corcoran Gallery featured a miscellany of mostly American art. Taken together, no public gallery in the nation’s capital could equal, much less surpass, the holdings of a typical provincial Italian museum.

When news of his offer became public, Freer was agreeably surprised by its favorable editorial reception in major dailies. For their part, the cautious Smithsonian regents appointed a special committee, none of them experts on Asian art, to examine the proffered gift, then stored in his Detroit home. Led by Secretary Langley, the group included Dr. James Angell, president of the University of Michigan; former Missouri senator John Brooks Henderson; and Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, along with Bell’s daughter, Marian, as an all-purpose expeditor. For five days, the committee members examined Freer’s treasures, and their judgment was later described by Marian Bell: “The opinion of all regarding this priceless Oriental art was summed up in Senator Henderson’s remark, ‘The things were all very well of their kind—but damn their kind!’”

Yet Freer found a formidable ally in the White House. More than any predecessor, President Roosevelt had his eyes on Asia. While still an assistant secretary of the navy, Theodore Roosevelt in 1898 audaciously ordered Admiral Dewey’s Pacific Squadron to Manila Bay, thus planting the flag in the Philippines. Speaking as president in 1903, he informed a wildly clapping audience in San Francisco that “our mighty republic” had become a “power of the first class in the Pacific,” especially since the Panama Canal was already in prospect. “Before I came to the Pacific slope, I was an expansionist,” Roosevelt declaimed amid roars of approval, “and after having been here I fail to understand how any man . . . can be anything but an expansionist.”

Thus for reasons geopolitical as well as cultural, Roosevelt met with Freer, endorsed his offer, and on December 13, 1905, sent a letter to the Smithsonian Board of Regents urging accession of a collection with “hundreds of the most remarkable pictures by the best known old masters of China and Japan.” Should the regents demur, he added, “I shall then be obliged to take some other method of endeavoring to prevent the loss to the United States Government of one of the most valuable collections which any private individual has given to any people.” He followed up by inviting wavering board members to a White House dinner on December 14, 1905. With an Augustan flourish, Roosevelt minimized the legal perplexities and maximized the gift’s symbolic importance. On January 4, 1906—by Washington standards, turbojet speed—a telegram informed Freer that his conditions had been approved.

Freer was once again on the road, sea, and rail, as he often would be until 1911, searching for new treasures for his eponymous museum. As Aline Saarinen writes, “Freer, the ardent, diligent amateur-collector, buying for himself and his nation, had access everywhere. The dapper, fine-grained gentleman, always exquisitely dressed, doffed his derby, his straw boater, his black homburg, his white Panama, and charmed people everywhere. ‘I need all the training and coaching I can get,’ he wrote home once, ‘I don’t want to buy promiscuously until I know.’”

He took care not to advertise his affluence, using strategies he confided to his old business partner Frank Hecker. In Peking, his target was the so-called Tartar City, the ramshackle neighborhood where antiquity shops proliferated. There he rented an unprepossessing suite of rooms, explaining to sellers that he was a humble buyer for an American auction house. “I will allow no one with things to sell to see me in my hotel,” he reported to Hecker, “thus preventing the guests in this large and excellent hotel [Grand Hotel des Wagon-Lits], excepting two or three reliable Americans, to learn of my plans.” As Freer added in a subsequent note, he initially hoped in Peking to find examples of early paintings dating to the Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties, but the results carried him off his feet: “Had I during all my stay in China secured a full half-dozen specimens of the great men of the dynasties just named, I would have considered myself extremely lucky. But the fact is, I have already in my possession here, over ten times that number.” In sum, “It beats California in ’49!”

As he also reported to Hecker, “The glimpses I am getting of old China during this hurried trip confirm the impression I have received from various sources. . . . In comparison, Japan seems only an imitative doll!” Hence his determination to widen his travels considerably in what became his final Asian trip, in 1910–11. After consulting with Chinese friends and American diplomats, he planned to explore the interior on his own, by railroad where feasible and otherwise by cart or pack train, with appropriate guides and bearers. Major destinations included the ancient Chinese capitals of Kaifeng and Luoyang, neither of which had foreign “hostelries” but each with a missionary presence. On this visit, he became one of the first Western travelers to explore the Buddhist cave complex of Longmen, then a battleground pitting brigands against less-than-efficient government forces.

The physical dangers were omnipresent. As Freer wrote in his journal, “En route here my photographer was stoned, received an ugly blow over his right eye . . . the dropping of a pin now startles him. My cook sleeps with the new bread knife I bought in Peking . . . the photographer never sleeps, my servant wept last night when the temple cay mewed outside; so if the brigands overpower the guard, I shall dive under my folding cot.”

It is hard not to respect his energy and devotion, yet also to wonder at his daring. The Qing dynasty was already teetering, and Longmen was deep in the remote hills southwest of Peking. Freer’s passage was eased by litter bearers, gourmet dinners, thirty attendants, and a guide with a peacock feather. This did not lessen risks. When he finally reached Longmen, his Chinese guides prudently assigned an armed guard to shield him from the opium-crazed bandits then infesting the region. He initially assumed that this was mere politeness and was shaken when local authorities arrested and tortured two murder suspects.

That evening, as he prepared to sleep, he was awakened by the gunfire of his guards. They explained that they were firing blanks to keep bandits at a distance. Freer asked them to desist. The next morning, he found that his guards had taken his order literally and had not used their guns but had silently slit the throats of the marauders, whose corpses lay outside his doorway. Unfazed, borne in a sedan chair, he inspected the celebrated caves. Freer’s description, as cited by the art historian Helen Nebeker Tomlinson, deserves extended quotation:

Here two mountains are separated by a narrow and swift running river—the cliffs of rock rising abruptly from the water are pierced by hundreds of temples and grottos, into which thousands of most beautiful Buddhistic figures, from two inches to sixty feet high, have been carved out of the rock. These deities are surrounded by flying angels, floral arrangements, scroll and other designs, all also carved in the rock. These were done 1500 years ago. When the sculptors quit . . . nature completed these masterpieces by softening lines and tones. . . . I quiver, thrill and wonder like an idiot. . . . I am not exaggerating! These supreme things compel reverent and constant attention. . . .

Even as he was astonished and inspired by these Buddhist caves, Freer was also troubled. Before leaving Peking, he had made arrangements with the American legation to export some large stone statues. He confessed to Hecker that he was “ashamed to ask for so great a favor,” but in plain fact he knew “it was now or never.” He was also aware, while in Longmen, that his battalion of bodyguards, in seeking his favor, might steal whatever objects he seemed to like. Many of the trophy works offered to him were plundered by bandits or other agents for dealers. So what should he do? As Tomlinson phrases his dilemma: “Should he grasp the opportunities, then justify his actions by the care the objects would receive under his guardianship and further by the education they would afford to thousands of Americans? Or should he righteously assist the Chinese government in shutting off the exodus of its artistic heritage?”

Charles Lang Freer’s party, settling in at the Longmen caves in 1911.

The record suggests that Freer leaned both ways. On the one hand, by December his acquisitions filled eleven cases and totaled more than two hundred objects. In his extensive purchases, he sought to distinguish between objects with religious or patriotic significance and those he could acquire with a clean conscience. “One suspects,” writes Tomlinson, “that the line wavered according to personal risk, potential for success, and jeopardy to his good name.” On the other hand, when he returned to America, he said in an interview with Detroit newsmen that he intended to “ask the U.S. Government to appoint a commission for the rescue [of] the priceless art of the ancient capitals of the Chinese empire and the bringing of them to the world through American scholarship.” And Freer actually did try, at some personal cost, to carry out that promise.

On his return, Charles Lang Freer planned to devote his remaining years to maximizing the benefits of his fortune and his hard-earned knowledge. He undertook three great tasks. He wished to sift and refine his promised collection, eliminating forgeries or works that fell below his exacting standards. In consultation with the Smithsonian, he hoped to reach agreement on a suitable design for his named gallery, to which he had already offered to contribute $500,000 in construction costs. Finally, he also hoped to promote concrete steps toward the preservation of China’s imperiled artistic treasures.

In all this, Freer shifted his principal residence to New York, while continuing to store most of his collection in Detroit. He always liked the city, and with the outbreak of World War I, it became the world’s leading market for museum-quality Asian art. European dealers upgraded their galleries in New York, the way led by the Chinese-born C. T. Loo. Equally important, following the collapse of the Qing dynasty, streams of high-quality objects with real or bogus imperial pedigrees began flowing to Manhattan. Freer became an active seeker and buyer, along with his new and special friend, Agnes Meyer, then in her early thirties, with whom he had something more than a flirtation but less than an affair. The wife of the financier Eugene Meyer (subsequently proprietor of The Washington Post), Agnes was magnetic, voluble, and eye-catching. He joined with her in touring major art showrooms. As to their relationship, the biographer Carol Felsenthal offers this guarded analysis: “Freer had a sexual interest in women—he and architect Stanford White once hired young Italian girls to swim nude before them when they dined in a grotto at Capri—and it was gossiped without evidence that Freer had congenital syphilis and chose to be celibate in his later years. To Agnes he was an ‘aesthete in every phase of life—in his home, in his appreciation of good food and wine, above all in his love of beautiful women.’”

Together they combed New York galleries for Asian works, and in his will Freer stipulated that Agnes Meyer was to be a lifetime trustee of his gallery, with veto power on acceptance of future donations of art. As to Freer’s purchases, they are documented in detail by the art scholar Daisy Wang. Freer bought no fewer than 1,611 pieces from 1915 to 1919, including 124 premium works from C. T. Loo, priced in total at $900,840. Presciently, his purchases included a large collection of antiquities predating the Ming dynasty, which then formed the core of the Freer collection—though these earlier works were less popular. When the Freer Gallery opened in 1923, Agnes Meyer commented, “[I]f European scholars must now come to America to see the finest examples of Chinese painting, Chinese jades and bronzes, it was because of Freer.”

All Freer’s tasks were complicated by his declining health, by America’s entry into the War to End All Wars, and by his reliance on all-too-human emissaries. He was stricken in 1917 by a disabling nervous disorder that shrank his weight and led to uncontrollable spasms of irritation and memory loss. He was acutely aware of his mortality, as Wang writes, but found solace in his belief that Chinese jade possessed magical healing qualities and, indeed, could be viewed as a metaphor for an ancient art providing a remedy for the diseased modern West. Dr. Wang quotes Agnes Meyer as observing, “When desperately ill at the end of his life, he would cling to certain pieces of jade with deep satisfaction and with an almost religious faith in its comforting and restorative powers.”

Even while stricken, Freer managed to collaborate with John Ellerton Lodge, soon to be the Freer Gallery’s founding director (and son of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge), in carefully transferring his collection from Detroit and other venues to Washington. Totaling 15,434 objects, his treasures were grouped into 1,270 paintings, drawings, and sculptures by Whistler, including the celebrated Peacock Room (see color plates, figure 1), and by other, mostly American, artists; 3,399 Chinese objects; 1,937 pieces from Japan; 1,095 Egyptian antiquities; 471 Korean works; and 5,847 Near Eastern objects (counting the single pages of illustrated Persian books and minuscule beads). To this founding aggregate, some 10,000 or more objects have been donated since the formal opening of the Freer Gallery of Art on May 3, 1923, four years after its benefactor’s death.

On the matter of authenticating and dating each and every item, Freer’s attitude can fairly be described as good-humored resignation. As he wrote to Agnes Meyer, he was untroubled by the likelihood that later “lynx-eyed critics” might challenge the authenticity of any prize paintings: “A yell will go up! Good! I hope it will reach me in some spirit way. Then will come what you call the ‘reasoning and scientific era’ to awaken study, to learn the hows and whys of production in China—the ideals, the materials, the means, the copies, the why. Intelligent people will strive for the knowable—a foolish adventuresome collector will be forgiven even if his flowers prove to be thorns—educational thorns that helped others.”

Nor did serious differences arise regarding the gallery’s design. A prominent site was chosen, west of the landmark Smithsonian Castle, traditional base of the Institution’s governors. Freer abhorred flashy marmoreal ostentation, and agreement was reached on a low-lying, classically austere building, constructed of subdued Tennessee white marble and Indiana limestone. Ample storage space was provided for objects not on display so that they could be studied by researchers. Nowhere was the donor’s full name inscribed, nor was Freer’s portrait prominently displayed at the entrance. As designed by Charles A. Platt, the gallery exudes calm and dignity and was nicely praised by the artist John LaFarge as “a place to go and wash your eyes.”

Freer died on September 25, 1919, a few months after the passing of Theodore Roosevelt, his most potent supporter. He was buried in his hometown of Kingston, New York, but his most fitting memorial, as described by Aline Saarinen, is a monument to his memory erected by the Japanese in a suburb of Kyoto: “It is a natural rock, suave and beautiful in form, about three feet high and six feet long [and] at the dedication ceremonies, the Japanese placed tea and champagne on the rock.”

Yet an important loose end remained. It was Freer’s plan to help establish a School of Archaeology and National Museum in Peking so that the Chinese themselves would have the skills and incentive to protect their own endangered antiquities. To that end, he recruited Langdon Warner to conduct a wide-ranging scouting mission to test the feasibility of Freer’s initiative. Warner traveled 12,385 miles in China, Indochina, and Europe in 1913. In all his interviews, he stressed (as his final report to Freer notes) “that we came to learn from China and the Chinese, not to remove objects of cultural importance, and asked for the goodwill of Chinese scholars in our enterprise.” He pointedly added that “I had been expressly instructed to make no purchases of objects of art or antiquity, and that this would be the policy of the School when started.” Warner arrived as China’s new republican regime had assumed power following the demise of the Qing dynasty. He conferred with the new government’s president, Yuan Shikai; its foreign minister, Sun Pao Ch’ih; and a host of other officials, diplomats, curators, and dealers. When meeting with President Yuan, the matter of excavations arose, to which Warner replied: “I was instructed to make clear that nothing of the sort would be undertaken without the official consent of the Chinese government and the good will of the people of the district where I was proposed. The President replied that such consent and goodwill would be most certainly forthcoming where our plans did not include disturbing the ancestral graves of existing families.”

Initially, Freer’s project stirred favorable comment, but it all went awry. Freer was a meticulous bookkeeper, and Warner did not share his accountant’s mentality in traveling widely with his wife, Lorraine, in Europe and Asia. He was especially irritated by Warner’s failure to go to Xi’an, owing to Langdon’s concern over local banditry. But it was the escalating and bloody turmoil of the Great War that took initiatives like Freer’s wholly off the table.

In a sad and ironic historical twist, the Freer initiative perished, while Langdon Warner would find reasons, elaborated in chapter four, under the guise of rescuing them, of stripping away Buddhist paintings and sculptures from Dunhuang.