The View from the Middle West

In ways that seem obvious, and others less so, the Second World War and its aftermath deeply affected the collecting, study, and selling of museum-quality Chinese art in America. An interwar generation of curators and scholars not only saw military service in the Pacific, but in postwar Japan its members served as Monuments Men, charged with salvaging and repatriating art treasures. Yet unlike their counterparts in Europe, they have yet to be cinematically celebrated. Initially and opportunely, senior officials in the Arts and Monuments Division of the occupation forces also shopped for bargains in China as well as Japan. With the advent of Mao’s People’s Republic in 1949, such shopping ended in mainland China. Inventive dealers in Chinese art now sought prizes in private collections, and some even scoured garage sales to feed an ever-growing market. For their part, American curators scrambled for fresh ways to draw visitors to their galleries by promoting international loan shows. The way was led in 1961 by a five-museum tour of “Chinese Art Treasures,” featuring superlative works from the National Palace Museum in Taiwan (“inherited from the former imperial court in Peiping”). Finally and more broadly, the longtime hegemony of America’s East Coast museums was challenged postwar by a new breed of Midwestern curators.

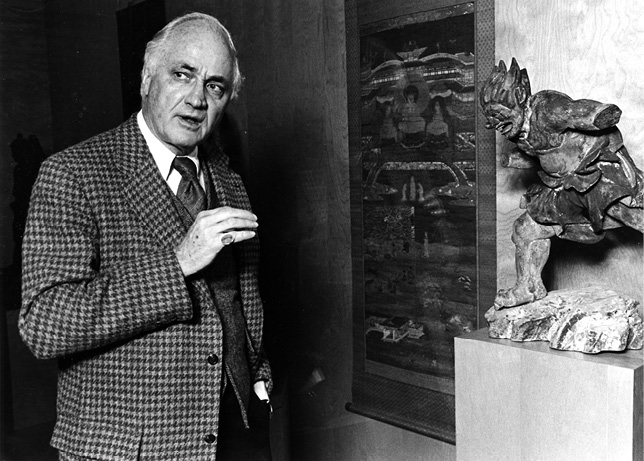

Cleveland’s Sherman Lee, who remarked that he was the first Asian art curator who didn’t attend Harvard.

No one better personified the regional shift than Sherman Emery Lee, a confident generalist with a superlative eye and a substantial budget. Through his widely read books, his lectures, and his role as director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Lee established himself as a connoisseur with firmly reliable views. His friendly rival and frequent collaborator was Laurence Sickman, also a former Monuments Man, whose prewar career in China we have related in earlier chapters. What Lee was to the Cleveland Museum, Larry Sickman was to the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City; each acquired Asian masterworks in cities that proudly and unexpectedly established public shrines for a genre of art whose appreciation requires patience and study.

Sherman Lee was born in Seattle, where his father was an electrical engineer employed by the government to help midwife the birth of a new, federally encouraged medium: radio. Soon Emery Lee and his family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where Sherman came of age, having attended local public schools. Their next move was to Washington, D.C., and here he developed “a passionate interest in art history,” having spent hours examining the Impressionist and Postimpressionist works in the Phillips Collection. He switched his major from science to art history and earned his B.A. and M.A. at American University. There in 1938 he met Ruth Ward, to whom he would be married for sixty-nine years. “He was a tennis player and she was a sorority girl,” according to their daughter Katherine.

Ruth and Sherman are well portrayed by Mary Ann Rogers, a longtime friend of both: “She is a perfect match for Sherman’s wit. Her character is solid and strong as steel, yet her words always flow with a magical, irrepressible Southern rhythm and charm, passing over Sherman’s silences and stony reserves like a river in summer. ‘She civilized me,’ says Sherman, a process likely begun after the honeymoon he himself arranged—a trip spent roughing it in the mountains with a tent and sleeping bag as the only amenities.” Honeymoon over, the couple moved on to Cleveland, where Sherman earned his doctorate in art history at Case Western Reserve University. His thesis, “A Critical Survey of American Watercolor Painting,” was among the earliest dissertations on its genre. At this point he chanced to take a summer course on Chinese art at the University of Michigan. His teacher was James Marshall Plumer, who for fifteen years lived in Shanghai and Fuzhou while serving in the stand-alone and potent Chinese Maritime Customs Service. Ceramics were Plumer’s specific passion. He had pioneered the identification of major imperial kilns, and his teaching technique was original. He would explain the differences between major kilns, then hide old Chinese shards beneath a cloth and ask his students to identify, only by touch, the provenance of a given fragment. Through such hands-on techniques, as Lee later recalled, Plumer introduced him to “the mysteries and practicalities of Asian art.” Plumer’s interests, it should be added, also included Buddhist sculptures, Rajput miniatures, Japanese “flung-ink painting,” and ancient Chinese bronzes, enthusiasms that infected Lee.

As a recent Ph.D. and encouraged by Plumer to enter the Asian field, Lee became a volunteer intern at the Cleveland Museum of Art, working with Howard Hollis, then the curator of Asian art. There, under Hollis’s tutelage, he helped mount an exhibition of Chinese ceramics that opened in spring 1941. That same year, he moved on to the Detroit Institute of Arts, having attained the rank of curator, and in what became a lifetime hallmark, he began writing short articles on a wide range of subjects: Chinese ceramics, Cambodian sculptures, and American watercolors (among others). Yet at this point, Lee had never set foot in Europe or Asia. His travels began in 1944 after he enlisted in the U.S. Navy, earned a commission as an assistant navigator, and a year later was finally able to reach mainland China. Shortly after the Japanese surrender in 1945, his boat docked in Tanggu, the nearest port to Beijing, with no further orders. Ensign Lee told his captain, a fellow fly fisherman, that he very much wanted to go to Beijing. He was allowed three or four days but was warned that he risked AWOL charges if he missed his deadline. Here is Lee’s firsthand account:

So I got a ride with a marine up to Tianjin and took a train crowded with people to Beijing. It was during the time when the communist guerrillas, as they were called then, were fighting the Guomindang soldiers in the hills. We had to stop a number of times because of the squabbles, but I was so excited; I was actually going to see Beijing. [The train finally arrived; he was in his naval uniform, but he found a rickshaw and went straight to the imperial palace.] I went to the north gate where the caravans with their camels formed up. The city walls were all still standing, and the walls and all the residences were painted yellow, pale pink, and pale blue, and Beijing was just unbelievably beautiful. Then I found where some of the antique dealers were in Liulichang. . . . I saw this Cizhou pillow . . . decorated with a beautiful landscape and figure painting. I really had so little money, but I just grabbed it and of course it cost nothing—around US $2.50, so it was ordained in heaven that one started with Cizhou.

Lee’s find collected from his first trip to China, a Cizhou pillow now in the Seattle Museum.

“That’s how it all began,” Lee said of his initial purchase, which now reposes in the Seattle Museum of Art. The Cizhou pillow was both a bargain and a splendid crossover piece marking the debut of a curator committed to finding wider audiences for all forms of Asian art. Produced in quantities in kilns in China’s northern provinces, Cizhou ware is sturdy, is boldly decorated with incised designs, and dates to the golden era of the Song and Yuan dynasties. The leaf-size stoneware pillow is intended for use in this life or (perhaps more comfortably) in the next, and its accessible images glow from beneath a transparent glaze. One quickly senses how and why Chinese ceramics so precociously became a global commodity.

Postwar, fortune again favored Sherman Lee. His Cleveland mentor, Howard Hollis, had been recruited to direct the Art and Monuments Division of the Allied occupation in Japan, and he invited Lee, then age twenty-eight, to become his chief aide. A year later, when Hollis returned to the United States, Lee assumed his duties. For two years, it became his task to inspect and inventory the country’s great art collections in order to help evaluate what had been destroyed and how to preserve the rest. In a letter to General Douglas MacArthur, the Chinese Nationalist government claimed that a number of objects had been looted during the war and were said to be hidden in the Sho¯so¯in, Japan’s greatest collection of ancient treasures, in Nara. Lee was given unique access to the imperial repository. Eventually, an exhibition was held of the looted material, but it proved small pickings. According to Lee: “It filled one good-sized dining room and the chief display was an eight-panel jade screen. It was weird. There really hadn’t been much looting at all, and nothing of interest.”

Lee used his unique position to inspect sites that had long been closed to the public and to see works of art that had not been on display, thereby forming lasting relationships with Japanese collectors, dealers, and art historians. Moreover, he sealed his friendship with Howard Hollis, who now chose to become a dealer, and he met Laurence Sickman, who, after his wartime service in China as a combat and intelligence officer, also became an advisor to the Monuments Division in Tokyo. And in yet another auspicious turn, as Sherman Lee’s own tour was ending, his old Michigan professor James Plumer also joined the team as an advisor. Thus a convergence of like-minded museum curators helped form the groundwork for a significant shift in the collecting priorities of key Midwestern museums. Moreover, owing to postwar economic conditions in Japan, where Japanese collectors were pressed for funds, the Monuments Men were able to collect art at moderate prices and, as important, to export their finds legally.

On his return to America in 1948, Sherman Lee assumed a promising new post as assistant director at the Seattle Museum of Art. The museum’s founding director, Dr. Richard E. Fuller, and his mother, Margaret MacTavish Fuller, were the major donors. From the museum’s opening in 1933, they had turned their gaze eastward. Initially, European art was only represented by color prints of well-known masterpieces, and priority was given to acquiring Japanese and Chinese stone sculpture and jade. The Fullers had more enthusiasm than cash, but before Lee arrived, Director Fuller provided his new assistant with $5,000 to shop in Japan, resulting in significant additions to the collection. Lee also persuaded the Kress Foundation to provide works by major European artists. Subsequently, owing to his close ties with Japanese collectors, Lee on a modest budget expanded Seattle’s holdings of Japanese and Chinese paintings, the latter notably including Hawk and Pheasant, an album leaf attributed to the Southern Song master Li Anzhong (active circa 1120–60), formerly in the Kuroda collection in Japan.

In 1952, he joined the Cleveland Museum, where the legend of Lee as the connoisseur par excellence really began. Unable to read Japanese or Chinese, Lee depended on the assistance of his associate, the Chinese-born scholar Wai-kam Ho, who would succeed him as curator of Oriental and Chinese art in 1958 when Lee became director. Just before Lee’s ascent, a local mining and shipping magnate, Leonard Hanna, bequeathed $35 million to the museum: half for operations and half for acquisitions, a wise stipulation in Lee’s view, since it ensured the gallery’s fiscal health.

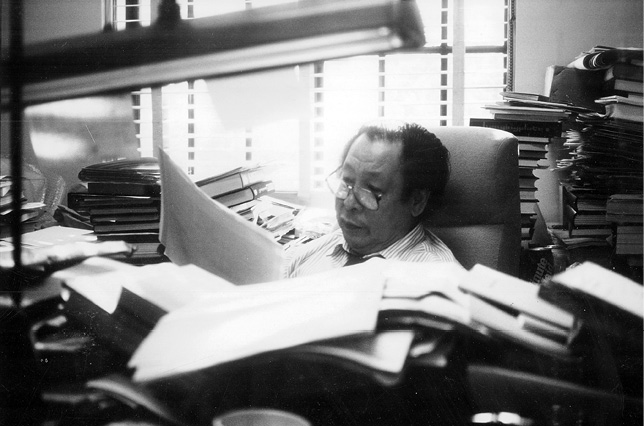

The erudite Wai-kam Ho, who was Sherman Lee’s indispensable collaborator in Cleveland.

As the buying began, according to Wai-kam Ho, Lee rewarded successful treasure hunting with a dry martini, and within a decade the two assembled one of the five great painting collections outside China. Their “symbiotic” partnership (as James Cahill has written) joined Lee’s eye and phenomenal memory for objects with Ho’s remarkable erudition. Wai-kam Ho’s unparalleled knowledge of Chinese written sources, seals, and inscriptions bore fruit in a 1980 exhibition, “Eight Dynasties of Chinese Art,” featuring three hundred paintings drawn from both the Cleveland and the Nelson-Atkins museums. (Kansas City’s director Laurence Sickman and Cleveland’s Lee were not above gloating that they had thus stuck a thumb in the eye of the Metropolitan Museum, then boasting its own acquisition in 1973 of twenty-five paintings from the C. C. Wang collection.) Lee and Sickman were among the first to celebrate the beauty, relative availability, and collectability of paintings from the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, as featured in their joint exhibition.

We owe to Wai-kam Ho an informed assessment of his director’s distinctive strengths: “Sherman is one of the very few non-Asians who does not depend on linguistic ability for his connoisseurship in Asian art. He cannot read Chinese or Japanese. Yet without being able to read inscriptions or signatures, he can tell a Shitao from a Zhang Daquin better than most Chinese art historians. His secret is what he calls being born with a pair of good eyes and having a keenly cultivated sense of intuition.” Lee rejected the notion that esoteric scholarship was essential to grasping the excellence of Asian art. Yes, knowledge of context was important, but, “We can never see Chinese art as a Chinese does, much less can we hope to know it as it was in its own time.” Writing in his well-received History of Far Eastern Art (revised edition, 1973), he amplified:

Again, a broad view, especially of style, is of the greatest importance in recognizing that the art of the Orient, like that of the Occident, is not a special, unique, and isolated manifestation. . . . Seen in this light, without romantic mystery as well as without the paraphernalia of esoteric scholarship, the art of Eastern Asia seems to me more readily understandable, more sympathetic, more human. . . . [H]ere are thousands of still meaningful and pleasurable works of art, part of our world heritage—and we should not permit them to be withheld from us by philologists, swamis, or would-be Zen Buddhists. What are they? How are they to be related to each other? What do they mean to us as well as to their makers? These are proper questions for a general study.

Still, if not a blind spot, Sherman Lee did have deep-rooted preferences. His friends called him “a serious petromaniac,” that is, someone fascinated by rocks. This can be discerned in the journal he kept during his breakthrough 1973 visit to China as leader of a North American art and archaeology delegation. As excavated (an apt verb) by the scholar Noelle Giuffrida, “incurable petromania” runs through his entire travel diary. It is “dotted with notes about the rocks he saw all over China,” she found, “including large specimen rocks in gardens, miniature examples, and desk-sized stones he noticed in galleries and shops.” Suitably enough, one of Sherman Lee’s earliest and most publicized acquisitions in Cleveland was Streams and Mountains Without End, acclaimed as a key monument of early Chinese landscape painting. It is a seven-foot-long hand scroll rendered in ink and subtle tints on silk, with nine colophons recording its history, painted either around 1100 CE or from 1205 to 1380 CE, its artist and provenance both unclear. Lee described the work as a kind of ancestor of the motion picture, since “one can vary the frame by moving the rolled ends from right to left, or left to right, thus creating innumerable small pictures as well.” An interesting insight, surely, yet to an untutored layman, the only things that seems solid in this mist-ridden, cloud-blurred landscape are its jagged and jutting rocks, like so many irate thumbs pointing skyward.

The delegation of North American directors and curators whose 1973 trip to China reopened a long-blocked road; Sherman Lee in middle foreground, Laurence Sickman is on his left, and James Cahill, with glasses, is in the back row.

As the Cleveland Museum’s collections grew, Sherman Lee abjured showmanship and expressed disdain for the term blockbuster, a buzzword associated with the Hoving era at the Metropolitan Museum. In the 1990s, years after Thomas Hoving had resigned as director, Sherman Lee was heard praising a special exhibition in New York and remarking, “Isn’t the Met great! Not even Hoving could wreck it.” Such was the outlook that led John Canaday, then The New York Times’s chief art critic, to comment in 1970 that under Sherman Lee, the Cleveland museum had become “the only really aristocratic museum in the country.” After Lee’s death at age ninety in 2008, a reporter recalled Canaday’s remark and elicited this response from Hoving’s successor, Philippe de Montebello: “Aristocratic, yes, but in a meritocratic way. [Lee] carried a lot of weight in the community of museum directors. He bought in all fields, his own particularly brilliantly, but in many different fields. He really transformed the Cleveland Museum from a regional museum to a major global museum.”

Yet his was far from a solo performance. Not only did he benefit from the learned insights of Wai-kam Ho, but he listened carefully to the observations of leading dealers, whom he praised and respected. This was not unusual. By now, the reader may have noticed that major collections often result from partnerships, typically when collectors, curators, and dealers seek advice from each other. In the case of dealers, there was the notable pairing (among many) of Laurence Sickman with Otto Burchard; Abby Rockefeller with Yamanaka; and J. P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller Jr. with Joseph Duveen. But perhaps no partnership proved as fruitful as that of Sherman Lee with John D. Rockefeller III and his wife, Blanchette, originating in the early 1960s, when Lee was still curator of Asian art at the Cleveland Museum. In linking Asia to the wider art world, Blanchette led the way; she followed her mother-in-law, Abby, and her brother-in-law Nelson, to the board of the Museum of Modern Art. Yet it was not until she and John III visited Japan in 1951 that they both began collecting Asian art, albeit on “an intermittent and amateurish basis.” John was nearly sixty when he turned to Sherman Lee for advice. Unlike his father, John Jr., who favored buying in lots, John and Blanchette concentrated on fewer objects of high quality. Their core collection, which is on rotating display at the Asia Society Gallery in New York, is strong in ceramics, sculptures, and bronzes. While John Jr. collected multicolored Qing dynasty enameled porcelains, his son sought earlier celadons and stoneware. In fifteen years the couple assembled a superlative collection, which they donated to the Asia Society in 1974.

Its selection owed a great deal to a civilized agreement reached between Sherman Lee and John D. Rockefeller III on dividing up the prizes, thus avoiding on Lee’s part a potential conflict of interest. As Lee wrote, “He faced the problem with characteristic wisdom and thoroughness. . . . It was both simple and direct: whatever he saw or was offered first was automatically at his option; whatever I or any other museum saw or was offered first was at the option of the museum. Should there be any confusion or simultaneity of offer, it would be decided by chance—in the only case that developed, by the flip of a coin.”

After 1949, mainland China was off-limits, so most of their acquisitions came through dealers and auctions, many of them in Europe. Like another great connoisseur, Denman Ross, Lee believed in working directly with objects, building “by comparisons over a long period of time.” His letters to Rockefeller are full of comparisons. He cautioned John III against buying an object if there were other good examples around, or if his collection already contained something as good. A letter dated March 4, 1965, from Lee to Rockefeller sets out their criteria for purchases:

- pieces that are really outstanding in the world, maybe none or only one or two or three others of equal quality;

- pieces that a first-class museum would be proud to have as part of their collection;

- pieces that would be acceptable to the better museums; and

- pieces that neither museums nor ourselves should consider of sufficient quality to include in our collections. . . .

“Based on this proposed system,” he goes on, “my feeling is that we should look hard for pieces in the A category, realizing that we will not often find them; and generally speaking be prepared to accept others only in the B category. C it would seem to me would only be considered where we found a piece that had particular appeal such as my pair of Han horses or whatever they are.”

When the collection opened to the public in 1974, the Asia Society issued a press release with a quote from Lee: “The rationale behind the collection is one that insists on the highest possible quality in the objects acquired and on their capacity to be understood and enjoyed by the interested layman rather than only to be studied by the specialized scholar. . . . The development of such a collection as this in the relatively short time since World War II was most fortunate and it is doubtful if it could be done again at the level attained.”

Among the jewels in the collection is a blue and white platter produced at the great Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi Province, with a very special inscription. These large platters were coveted in Muslim lands, where food was commonly served to groups of diners. What sets this splendid porcelain dish apart is an inscription, written in Farsi, naming the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, who during his reign (1627–58) created the Taj Mahal, a memorial to his beloved wife. The emperor was known for his regard for Chinese wares, and this Yuan-era platter is among the few that had been preserved in India with Shah Jahan’s presumed mark of ownership inscribed on its footing—early evidence of a culturally productive trading relationship between South and East Asia.

A final reminder of this productive modern-day, fifteen-year partnership is on display at the Cleveland Museum. After his patron’s death, Lee received a bequest from John D. Rockefeller III: a Japanese hand scroll by Shukei Sesson (1504–89) valued at $40,000, which Lee then presented to the museum in Rockefeller’s memory.

To this, a footnote should be added. No one has more closely traced Sherman Lee’s networking with dealers than Noelle Giuffrida, an assistant professor at his own university, Case Western Reserve. In researching a book titled Separating Sheep from Goats: Sherman E. Lee’s Collecting, Exhibitions, and Canon of Chinese Painting in Postwar America, Dr. Giuffrida found that Lee also benefited from his cultivation of a little-known German-Jewish collector named Walter Hochstadter, who escaped from Nazi Germany in the 1930s and became a dealer in Shanghai and Beijing, specializing in Chinese ceramics and paintings. Just before the Maoist victory in 1949, Hochstadter managed to export his prize works. Sherman Lee acquired seventy-five of his best paintings, although negotiations were “tumultuous,” according to the author, who contends that this timely purchase meant that the Cleveland Museum clearly possesses one of the finest Chinese painting collections anywhere.

Still, this was not the celebrity that Sherman Lee coveted. He liked fencing with dealers, partly for the love of the game. His respect for his better adversaries was expressed at the Cleveland Museum’s fiftieth-anniversary fete in 1966, when he said, “When a curator comes back and says he discovered an important art work, he really means a dealer discovered it.” He also remarked to friends, perhaps in jest, that if had to start all over again, he would become “a dealer.”

A dealer much after Sherman Lee’s heart was Robert H. Ellsworth, the “King of Ming,” a self-made and self-taught specialist in Chinese paintings and furniture, who did exceptionally well by going against the contemporary grain. The son of a dentist credited with inventing root-canal surgery, Ellsworth entered the Asian market in the 1960s as a protégé of the well-regarded New York dealer Alice Boney. His eye proved accurate and his market instincts sound; he early on built up a stock of post-1800 Chinese paintings, bronze mirrors, and Ming furniture just as the demand for each began to rise.

As the seasoned British auction writer Geraldine Norman reported in 1994, “His achievement in the Oriental field is that of the legendary Lord Duveen,” meaning that his own imprimatur ensured premium prices. John III was among his best customers, and in 1974 Ellsworth offered for sale a suite of vintage furniture—cupboards, inscribed chairs, couch, sideboards, tables—priced at $550,000, that he felt deserved display in the newly established Asia Society Gallery in New York. As he wrote Rockefeller, these were among the “truly great pieces that I own,” adding that he made the offer because it seemed “that this is the only way to secure a permanent home for my collection as well as to make some contribution to the field of Oriental art, to your museum and the City of New York.” Rockefeller’s response was favorable; various pieces did go to the Asia Society and the Metropolitan Museum, to which John III later donated Chinese paintings valued at $22 million. When Ms. Norman interviewed him in his palatial apartment at 960 Fifth Avenue, Ellsworth was reputedly the richest dealer in Asian art, having also been named an honorary citizen of China (another premonition of things to come). He died in August 2014 at the age of 85.

In short, post-1945, the market for Chinese art treasures was buoyant but risky, highly dependent on insider networking, and tilted in Midwestern eyes to the condescending Northeast. When we earlier encountered the younger Larry Sickman, he had parlayed a Harvard degree and a Harvard-Yenching fellowship into becoming a purchasing agent in China in 1931 for the then-under-construction Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. This was shortly after its trustees in Kansas City chose bravely to develop a small, half-century-old art gallery into a major all-purpose museum, with a collection and budget to match (see color plates, figures 2, 5, 15, and 16). The best buys then were in Asia, and Sickman provided the newborn museum in the 1930s with as much as 60 percent of its collection: 1,500 pieces in 1933 alone. In that year, the completed museum formally opened, Sickman finally met his employers, and he was shortly appointed curator of Oriental art, commencing a forty-year relationship.

After Pearl Harbor, Sickman returned to China as a U.S. Army Air Force major assigned to aerial bombing intelligence. By all accounts, his on-the-ground experience proved invaluable in identifying significant targets. In August 1945, two days after the Japanese surrender, he flew to Beijing to secure intelligence documents from the Japanese high command when an unexpected opportunity arose. Not knowing what to expect, Sickman brought with him $250,000 in cash. The money was not needed—the Japanese generals preferred to surrender to the Americans rather than to the Chinese—but the cash had other uses. What followed was recalled in 1977 by Marc Wilson, Sickman’s successor as director of the Kansas City museum: “The return flight to Chungking included a bomb bay packed with surrendered samurai swords and masterpieces by Shen Chou (Shen Zhou), Wen Ching-Ming and Lu Chili (Lu Zhi), the nucleus of the Nelson Gallery’s Ming paintings, all purchased with funds hurriedly and irregularly borrowed from a suitcase containing $250,000 belonging to the Quartermaster Corps.” Such are the fortunes of war, and Sickman’s loan was repaid in full. After the war ended, Sickman served as a Monuments Man long enough to win praise for his service and to forge a friendship with Sherman Lee.

By the time Sickman returned to the United States, his talents were well recognized in the curatorial trade, and prestigious job offers followed. He chose to remain in Kansas City, due to the generous support of the Nelson-Atkins trustees, but also because he had the rare chance to create, nearly from scratch, a world-class art collection. And Sickman was a collector by instinct and upbringing. He had an absentee father and a doting mother, May Ridding Fuller Sickman, a “Colorado Brahmin,” who collected Japanese prints and read Charles Dickens to young Larry every night in their Denver home. So enamored of Dickens did the ten-year-old boy become that he started collecting what became a complete set of first editions of the novelist’s major works. As to China, when asked by an interviewer what led him in that direction, Sickman responded, “I never wanted to go in any other direction.” The seed was planted during a chance visit to an antique shop owned by a family dynasty named Sarkisian, adjacent to the Brown Palace Hotel, then Denver’s grandest. “I made my first acquisition there at the age of thirteen—it was a pair of wooden figures, man and wife, Chinese of course. There wasn’t any question about it. I wanted to collect. If you are not totally acquisitive, you are not totally qualified to be a director of a museum.”

In 1953, Curator Laurence Sickman at age forty-six became the second director of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. By then, he had published a score of learned papers on Chinese wall paintings, Buddhist sculptures, and on his own museum’s Guardian Lion. He also collaborated with the architectural historian Alexander Soper on what became the gold-standard text, The Art and Architecture of China, which joined the Pelican History of Art series in 1953. By any standard, he and Sherman Lee played pivotal roles in changing the cultural landscape of the trans-Mississippi West. When Sickman entered Harvard in 1926, it was the only major university in which courses were offered on China’s language, art, and history. Yet fifty years later, as Marc Wilson noted in 1988, “there is not a single state in the union where Chinese literature language and history are not taught in institutions of higher education, and with an expertise unimaginable in 1926.” And as regards art museums, during that half century the Middle West ceased to be the “Sahara of the Bozart,” to use H. L. Mencken’s derisive term for Main Street America, South and Midwest, in the mid-1920s.

In this transformation, Sherman Lee and Laurence Sickman played an outsize role. Both prized quality over splash, both were object-oriented, both excelled at an essential trait needed for successful museum directors: waltzing with donors. Sometimes charm did not suffice. Sickman coedited the handbook for John M. Crawford’s collection of calligraphy and painting and offered valued advice, this accompanied with much handholding by his successor, Marc Wilson. However, when Crawford died in 1988, the same year as Sickman, the collection went to the Metropolitan Museum, which had enticed him with a newly built gallery.

There was an additional ingredient in the Lee-Sickman formula: each believed in outreach, at home and abroad. Not only did the Cleveland Museum and the Nelson-Atkins offer lectures and guided tours, but both also actively organized school visits so that local children could both learn and help dispel the gloom of empty galleries. But outreach has a wider dimension. So well regarded was Larry Sickman’s expertise that the Nelson-Atkins Museum was among the handful of American institutions invited to send high-quality works to the path-creating 1935 Burlington Exhibition of Asian Art at the Royal Academy in London—and this when the Kansas City gallery was but two years old. It would be the first time that China authorized the overseas loan of treasures from its hallowed and secretive Imperial Palace Collection.

It was with the hope that Nixon’s 1972 trip to China might similarly reopen doors for cultural exchanges that Sherman Lee helped promote, and then a year later headed, a twelve-member delegation of North Americans on a sixteen-city tour of the People’s Republic. The monthlong pace was rushed and tiring, and Lee later remarked that his role required “the combined talents of a shoe salesman and a diplomat.” Chairman Lee in fact excelled in both skills, supplemented by his agility at the Ping-Pong table and as a rock-loving mountain climber. Tall and formidably browed, the director towered over his hosts, but he kept his temper. But the culture gap proved formidable. “What we call the Bronze Age, they call the Slave Age, and what we call Feudal, they call Medieval,” he later commented to The Cleveland Plain Dealer. “There is no such thing as art for art’s sake, divorced from politics. They could not understand when we became excited because something is beautiful. In China, art is part of the revolutionary machinery.” And at every point, there was Larry Sickman to soothe, explain, and charm.

There is no doubt that the 1973 visit cleared the way a year later for “The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China,” the icebreaking show of shows, which opened for six months with suitable fanfare in Washington. But initially, Kansas City was not on the itinerary. Here is Marc Wilson’s account of what followed:

Through Larry’s connections and through Kansas City resident Leonard Garment, an advisor to Richard Nixon, it also came to the Nelson-Atkins. The Chinese then agreed to an extension so the Chinese population in San Francisco could see it. The National Gallery of Art had no Asian art curators, so I served as a kind of curator for all three venues and the Nelson-Atkins did the catalogue and installation. We were very limited as to what we could produce. Every word in every catalogue and label was censored. Things were so scary inside China that the Chinese wanted to see only pictures, so we decided to produce a good picture book with quality images and also a good installation.

Subsequently, a team of Chinese museum experts accompanied the traveling exhibition, their task being to make sure not a letter on the labels was changed. “They wanted desperately to look at our paintings,” Marc Wilson relates, “but it wasn’t permitted.” Still, the ice was broken.

In due course, Larry and Sherman passed into the emeritus status granted ex-directors of distinguished museums. Their relations had been mostly friendly, with a few wrangles over matters of attribution and acquisition. Like the classic millennium-old scroll painting Streams and Mountains Without End that both admired, their characters and tempers complemented each other. And like venerable Chinese scholars, both collected rocks. At his core, Sherman Lee was like the rocks rising into the mist—solid, stubborn, and unpretending. For his part, Laurence Sickman was as fluid as a stream, a seeker of evasive detours in a world abounding in violence and fanaticism. The last words belong to Sherman Lee, who in June 1986 wrote this note to Larry Sickman from his modest cottage in Chapel Hill, North Carolina:

Dear Larry: I have heard that you recovered from dire straits and I write to congratulate you and hope for your continued good health. I enclose a photo to attest to your good influence on our household in retirement . . . the view is of small enclosed garden off our bedroom. The rear rock is your honored gift. The nearer is one we picked up in San Antonio, evidently an outpost of your Ozark petrified garden. In any case, we like it and count it both a blessing and a reminder. You were most kind to give it to us and we hope the usual evidence of its continued use attests to our gratitude for your gift. Petromania is not one of the worst sins—indeed, it is a virtue, or so we believe. I think about Southern Sung and wonder whether it will ever coalesce in my mind. . . . Is it really too sweet or anxious for our taste? We enjoy our garden and retirement from the current version of “art museums.” All the best, Sherman.