If the great China collectors of times past congregated (where else?) at the legendary Long Bar in Shanghai’s British Club (now a hostel for sailors), one member would surely stand out: Avery Brundage. He was a muscular six-footer with an icebreaker visage who for decades dominated the International Olympics Committeee (IOC), and his breeding did not conform with the likely art-buying template. Brundage grew up in Chicago when its stockyards and politics were pitilessly chronicled in muckraking novels and criminal statistics. He flourished in the Windy City’s rough-and-tumble building trade before vaulting to global eminence during the Olympic movement’s most tumultuous decades. Yet throughout, Avery Brundage was drawn to the timeless serenity of Chinese art.

Indeed, even Brundage had trouble defining himself. “I’m a strange sort of beast,” he informed Robert Shaplen, who profiled him in The New Yorker in 1960. “I’ve been called isolationist, an imperialist, a Nazi, and a Communist. I think of myself as a Taoist. Actually, I’m a hundred-and-ten-percent American and an old fashioned Republican. People like me haven’t had anybody to vote for since Hoover and Coolidge.” Still, it seems fair to add that during his tenure as IOC president (1952–72), Brundage consistently seemed to believe that the end (i.e., “Let the Games go on”) justified getting along with Hitler, Mao, and Stalin, to the extent of praising their respective regimes’ generous support for athletics; and with much-criticized detemination, he ruled that the 1972 Munich Games should continue as usual after terrrorists massacred eleven Israeli athletes. He was not a person easy to imagine, or invent.

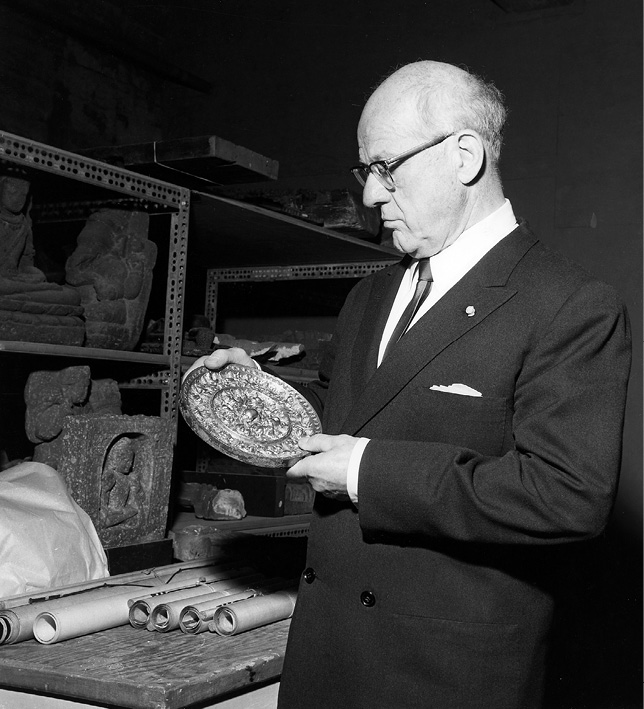

Avery Brundage appraises an ancient Chinese mirror in his extensive collection, gathered between his Olympic duties. “It’s not a hobby, it’s a disease,” he once remarked. © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Born in Detroit, young Avery was six when his father, a mason and builder, moved with his wife and two sons to Chicago, where Charles Brundage joined in the frantic drive to complete the monumental structures for the Columbian Exposition in 1892–93. Son Avery thereafter fondly recalled the Exposition’s “splashing fountains” and “handsome buildings,” though his subsequent early years were darkened by his father’s abandonment of his family. Minnie and her two sons survived in a minimalist South Side flat. She worked as a store clerk in the Loop, and Avery delivered newspapers while attending the local manual training high school. There he excelled in both his studies and on the track team, as he likewise did upon entering the University of Illinois in 1905, where he also earned extra money as a railway track surveyor in the Chicago area.

In 1909, the same year that he became the Big Ten discus champion, Brundage graduated with a degree in civil engineering. He was promptly hired as a building inspector and construction superintendent by Holabird & Roche, a leading architectural firm. As detailed by Maynard Brichford for the Illinois State Historical Society, the freshly graduated Brundage supervised $7.5 million in construction work, roughly 3 percent of all new building in the city. We may assume that he also acquired a postgraduate degree in Chicago’s intricate mesh of zoning, building codes, ethnic politics, and pervasive graft.

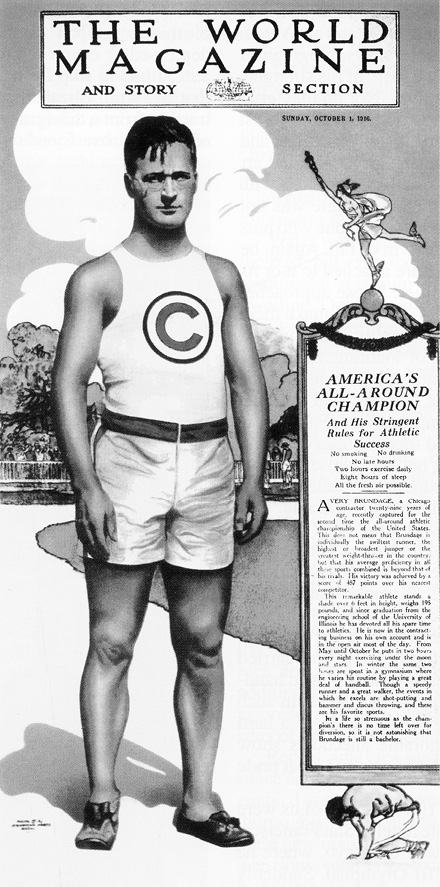

During these formative years, Brundage intensified his schoolboy devotion to track-and-field athletics. He resigned his job to compete in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, in every sense his revelatory moment. While he won no medals in the decathlon contests at the Games, every two years from 1914 until 1918, he earned and held his title as America’s “all-around” champion in ten track-and-field events. His face and name adorned sports pages and magazines, which proved an asset as he clawed his way through Chicagoland’s entrepreneurial jungle. “Avery Brundage was big, strong, agile and fast,” in Brichford’s summary of these early years: “Brundage capitalized on his fame as an athlete, but his intelligence and competitive drive carried him far beyond his career as a track man.”

He was only twenty-six in 1915 when he founded the Avery Brundage Company. After America entered the World War two years later, Brundage applied unsuccessfully for a commission in the Ordnance Corps, then joined with other firms to speed-build military facilities. Ahead lay the Windy City’s phenomenal postwar boom, propelled by Prohibition (a windfall for organized crime), Great Lakes shipping, strategic rivers and waterways, a network of transcontinental rail lines, plus surging grain markets, new factories, expanding stockyards, jazz clubs and strip joints, a flood of migrants, outstanding universities (Chicago and Northwestern), and a pride of prominent writers and poets (e.g., Hemingway, Sandburg, Lardner, Hecht, Monroe) all chronicled by “The World’s Greatest Newspaper,” as The Chicago Tribune modestly described itself. “There is in America an incredible city named Chicago,” wrote a discerning British visitor, Rebecca West, in her 1926 preface to Carl Sandburg’s poetry, “a rain-colored city of topless marble towers that stand among waste-plots knee-high with tawny grasses beside a lake that has grey waves like the sea. It has a shopping and office district that for miles around is a darkness laid on the eyes, so high are the buildings, so cluttered up are the narrow streets with a gauntly striding elevator, and a stockyard district that for miles around is a stench in the nostrils.”

Chicago’s all-round Olympic star, as rendered in 1916 in The New York World’s Sunday magazine.

Avery Brundage contributed substantially to Chicago’s thrusting skyline during this unparalleled building boom. From 1923 to 1928, new construction in Chicago exceeded $250 million each year, peaking at $366 million in 1926. Brundage’s company initially concentrated on apartment buildings, many of them gleaming on the North Shore Drive’s “Gold Coast.” Next came a dozen substantial office buildings, followed by a cluster of hotels, including the Shoreland on Hyde Park’s South Side Drive (the city’s premier address for pols, mobsters, and visiting celebrities), along with banks, country clubs, and the Baha’i House of Worship in Wilmette, Illinois. His most ambitious industrial project was the Ford Motor Company assembly plant, which spread over sixteen acres under a single roof, its completion requiring 150,000 sacks of cement. The plant initially mass-produced Model Ts, then switched to Ford’s other brands, turning out 154,244 vehicles in 1950.

Inescapably, as the bubble burst and Wall Street plunged, so did Brundage’s commissions, which all but vanished during the Great Depression. Yet he navigated skillfully through hazardous straits. He founded the Roanoke Real Estate Company in 1932, through which he acquired ownership interest in buildings he had constructed in lieu of payments due him. In Brundage’s words, “you didn’t have to be a wizard” to “buy stocks and bonds in depressed corporations for a few cents on the dollar—and then wait. I was just a little lucky.” Not just luck. In a conversation years later with René-Yvon Lefebvre d’Argencé, the longtime keeper of his art collections, he described meeting a close colleague in Chicago in the depth of the Depression. The two friends started counting the number of people they knew who had recently committed suicide: “It added up to fifty.” (He earlier told the same story to Shaplen, but his total then was forty, and he added, “It is interesting to note that not one of them had any sports experience.”)

Like many struggling entrepreneurs in the New Deal era, Avery Brundage did not approve of WPA projects and Social Security, which he feared were plunging the country into socialism. On foreign policy, Brundage generally concurred with Colonel Robert McCormick, publisher of The Tribune, whose weekly radio broadcasts excoriated liberalism in all its guises. Like the colonel, Brundage was a fervent isolationist and a prominent member of the America First Committee. In August 1940, as cochairman of Chicago’s Keep America Out of War Committee, he invited Charles Lindbergh to address fifty thousand like-minded believers in Soldier Field. (The day after Pearl Harbor, both committees dissolved.) So ardent was Brundage’s antiwar passion that he unwisely accepted an invitation to address a German Day rally at Madison Square Garden in New York, sponsored by the pro-Nazi German-American Bund, which he had not previously heard of. He elicited roars of approval when he declared, “[W]e in America can learn much by observing and studying what has happened in Germany,” prudently amplifying, “if we are to preserve our freedom and our independence, we, too, must take steps to arrest the decline in patriotism.”

These and other remarks dogged Avery Brundage during and after his controversial tenure as president of the International Olympics Committee. Yet in our view, his tense and fractious Chicago years are essential to understanding his subsequent career as an Olympian and art collector. Affronted by the sleazy underside of politics Chicago-style, he idealized the playing field as a sanitized arena where strength of character and obedience to rules encouraged a free and fair contest among honorable competitors. He shared the hope that—as in classical times—an Olympic peace might prevail during the modern Games, which seemed to be the case following their resurrection in Athens in 1896. Yet from the first, there were also nettlesome arguments among participants, especially from rival major powers over flags, facilities, gear, rules, emoluments, sideshow features, and the proper role of women and ethnic minorities. For example, at the St. Louis Olympiad in 1904, the American hosts sought to illustrate the contrast between modern-day Greeks and barbarians by staging “native games” during two “Anthropology Days.” The “anthropology” competitors were Asians, Africans, and American Indians, all garbed in stereotypical costumes, thereby implying the subordinate role of lesser breeds; the “natives” competed for petty cash, it being assumed they could not grasp the Olympian ideals. Among those dismayed by this patronizing spectacle was France’s Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the chief inspirer of the modern Games, who later commented, “In no place but America would one have dared to place such events on a program.” Nonetheless, the Olympic mystique proved contagious, and participating in the Games soon became a popular and accepted extension of foreign policy by other means.

Such was the context as Avery Brundage ascended the Olympian heights. Having been elected president of the American Olympic Committee in 1928, Brundage then became the U.S. representative on the International Olympic Committee in 1936. One of his first missions was to sound out Germany’s recently empowered Nazi leaders, who were scheduled to host the Summer Games in Berlin, a venue chosen five years earlier when the country was still a democracy. Would the virulently anti-Semitic regime let qualified Jewish athletes join the German team? A good deal of head-scratching, mumbling, and double-talk followed, but Hitler’s spokesmen said they would abide by Olympic rules, as Brundage affirmatively assured the IOC.

By this time, opinion in the United States was closely divided between boycott-the-Nazis advocates and play-the-Games enthusiasts. Complicating the argument over racism was the embarrassing fact that nonwhite athletes (like the legendary Jesse Owens) were barred by Jim Crow codes from competing in mixed trials with whites (in the South) or from staying in the same hotels as white contenders (in the North as well as South). In Washington, President Franklin Roosevelt chose to remain silent, and when the American boycott movement lost traction, so did its counterparts in Britain and France.

Did the democratic world miss a real chance to slow or even derail the German juggernaut? In Nazi Games: The Olympics of 1936 (2007), the American historian David Clay Lodge, after combing relevant archives, offers this measured judgment:

We should remember that in 1933–36, the Nazi dictatorship was still a work in progress. . . . In the last parliamentary elections that Hitler allowed, those of March 5, 1933, the Nazis, even with all the intimidation they imposed on voters, had not managed an absolute majority, winning 43.9 percent of the total Reich-wide, and in Berlin only 34.6 percent. The effects of the Great Depression were still very much evident, with unemployment running high. . . . The Olympic Games were important to the Nazis because by hosting a successful festival the Reich could come across as a peaceful nation that was making economic progress at home and winning respect abroad. By deciding to show up in Berlin despite reservations about Hitler’s policies, the world’s democracies missed a valuable opportunity to undermine the regime’s stature not only in the eyes of the world, but also—and ultimately more important—in the eyes of the Germans themselves.

As the storm over the Berlin Games gathered, Brundage commuted frequently to Europe on Olympic business. In early 1936, while stopping in London, he happened to visit Burlington House to inspect what was commonly described as the most comprehensive exhibition of Chinese art yet assembled in the West. He studied the jades, bronzes, ceramics, and painting, including 735 works from the Imperial Collection in the National Palace Museum. “Awed by the splendor of it all and noticing the availability of Chinese works of art on the market, he began to conceive the grandiose project of amassing a collection of Asian art that would surpass any other private collection.” So writes Lefebvre d’Argencé, who adds that Brundage’s purchases were initially few and cautious, but gathered momentum during his 1939 trip around the world with his wife, Elizabeth. Their itinerary included Japan, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Saigon, Angkor, Bangkok, Penang, and Colombo. By then, Brundage had retired from active management of his firm, and the childless couple resettled in a spacious suite in the LaSalle Hotel (which he now owned) and acquired as a vacation home La Piñeta, a stylish Spanish mansion in Santa Barbara, California.

All the while he kept buying Asian art. “One of the first of a series of great coups for which he became famous,” writes Lefebvre d’Argencé, “was the formation of an unparalleled collection of ancient Chinese bronzes, which particularly appealed to him through their architectonic robustness, intricate delicacy of design and superior craftsmanship.” This surely sounds right, but there was another attraction that also seems credible. In filling his homes with Chinese art, Brundage was entering a realm very unlike his own. Here was a tradition and an aesthetic very unlike his everyday world. Here was a magic landscape populated by sage and calm scholars and their deferential female consorts garbed in silk robes, with badges indicating their rank, and here was a social order where rules were sacrosanct, down to the precise form of greeting suitable to each rank.

This is a surmise. Brundage himself did not venture beyond common clichés in explaining his devotion to Oriental art. “It’s not a hobby, it’s a disease,” he liked to say to friends. “I’ve been broke ever since I purchased my first object.” Well, to vary Evelyn Waugh’s useful demurrer, “up to a point, Lord Copper.” Brundage quickly became known for his ability to judge Asian art, and for his rule: “Top quality, low price.” It was also understood that he could return any object if he changed his mind about its merit. Wherever he went on Olympic business, he cultivated scholars and dealers. His official position was anything but a disadvantage. Abroad, he would seek advice on where bargains might be obtained from his host officials, and they in turn would invariably be anxious to please the IOC president—often presenting, in Godfather fashion, “an offer he couldn’t refuse.”

Brundage was hardly unaware but never acknowledged the confusion that his dual role might cause. Writing in 1960, Robert Shaplen described a typical instance: “Two years ago, when he went to Japan for an IOC meeting, he was able, he feels, to achieve the perfect synthesis of sports and art that to him represents the true Olympic spirit. He arranged in advance to be met at the airport by four Japanese, two of them Olympic officials and two leading Oriental art experts, and during the next two days he escorted the sportsmen to museums they had never seen and the arts specialists to sports they had never seen. ‘It was great fun,’ says Brundage, ‘and when I saw the Emperor afterward and told him what a service I had done for Japan, he agreed.’”

Abroad or at home, his key purchases required extensive vetting by museum curators, provided gratis or on the cheap in hopes of future institutional rewards. His ample homes were crammed with his prizes; visitors remarked on bathtubs filled with netsuke, while a famous Shang dynasty rhinoceros (later the logo for his collection) was packed in a shoebox. As his trove grew in size and variety in the late 1940s, the staff and director of the Art Institute of Chicago began to wonder what the childless Brundage planned to do with his treasures. “I got Brundage on the board,” recalled Daniel Catton Rich, then the institute’s director. “His collection paralleled many of the things we already had, and I went to Brundage and asked him for part of it. But he wanted a separate series of galleries. We kept the idea in mind, but meanwhile, San Francisco came along, and I advised Brundage to put his collection on the West Coast—to the great annoyance, I may say, of Charles Keeley, one of our curators, who had been advising Brundage on acquisitions.”

These initial soundings were owed in part to an initiative taken by the University of California (Berkeley) art historian Katherine Caldwell, a graduate of Paul J. Sachs’s museum course at Harvard. She saw in the Brundage collection an opportunity to fill an embarrassing gap in the city’s museum constellation. Despite its large Chinese and Japanese communities, and despite San Francisco’s reputation as the “Gateway to the Orient,” there was no local museum collection of Asian art of any consequence. Pragmatically, Caldwell realized that City Hall would become interested only if it were approached by a group of socially active and prominent Bay Area residents. She organized just such a group to meet with George Christopher, the liberal Republican who was then mayor of San Francisco.

Duly impressed by the high-powered appeal, Christopher arranged for Brundage to be named an honorary citizen of San Francisco. Next, accompanied by Gwin Follis, board chairman of Standard Oil of California (and likewise a collector of Asian art), Mayor Christopher arrived by private aircraft, with suitable brio, at Brundage’s winter retreat in Santa Barbara, a touch the mayor felt would lend the required drama to the occasion. At dinner, however, Brundage talked about everything except art. Finally, over coffee, Christopher blurted out the purpose of his visit (as the former mayor recalled in a 1975 interview): “Mr. Brundage, Chicago is a great city, Mayor Daley is a great friend of mine, but your collection is too important to go to an already-constructed museum. San Francisco is the Gateway to the Orient, it has large Oriental communities, but we don’t have any Oriental art to speak of. I want you to give this collection to us, and to see to it that it is displayed in the way you think best.”

Brundage then agreed to donate his collection to a purpose-designed annex to the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in Golden Gate Park. All costs were to be borne by the city. In due course, the City Council approved a bond issue for $2,725,000, which was submitted to a referendum in June 1960. To promote a “yes” vote, advocates of the museum, Gwin Follis among them, engaged the day’s most sought-after political publicists, Whitaker & Baxter. The firm came up with a film presentation, which ended with a flourish: “It is our great good fortune that this wonderful gift—one of the great gifts of all time—is ours for the voting!”

Not yet, not quite. The bond issue was approved by a substantial majority, and two days later Brundage initialed the preliminary plans for the new gallery. But after the wing was formally opened in 1966, it became public knowledge that according to the contract signed in 1959, half the collection remained the property of Brundage or the Avery Brundage Foundation. This was partly attributable to tax laws; since the allowable contribution for works of art could not by law exceed 30 percent of the donor’s annual income, there were palpable benefits in stretching a gift over a twenty-five-year period. This meant that Brundage could at any time legally withdraw half of his collection, a matter further complicated by the fact there was no agreed inventory of objects added to the collection since 1959.

Hence, until the gift was final, Brundage could withdraw the better half of his collection, a threat he now employed. Still, he could not be wholly blamed for taking advantage of a developing muddle. Brundage insisted that it was he, not the city, who was paying the salary of his handpicked director, Lefebvre d’Argencé. Going further, Brundage contended that his collection should be under the control of a separate board of trustees. He also complained about the lack of adequate humidity controls in his named galleries. He had other grievances as well. During one of his Olympic visits to the Far East, he arranged for art from Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan to be sent to San Francisco; however, he did not make prior arrangements for the city to pay the transportation costs. When San Francisco refused to pay the shipping bills, amounting to about $60,000, he had the artworks returned unopened to their countries of origin.

George Christopher’s successor as mayor was the colorless John F. Shelley, who flew in vain to Chicago in 1967 to appease Brundage. Later that year, a more charismatic mayor, Joseph L. Alioto, was elected. Having received a telegram from Brundage stating that he intended to move half of his collection to Los Angeles, Chicago, or Kansas City, the flustered mayor-elect took the next plane to Chicago. On entering the collector’s suite at the LaSalle Hotel, the mayor immediately noticed a framed certificate designating Brundage an honorary citizen of Los Angeles. “All right,” Alioto recalled saying, “I’ve seen the certificate. You can take it down now.” Yet despite this bold opening, he then yielded to the donor’s demands. He agreed to form a separate twenty-seven-member board to administer the Brundage Collection as an autonomous entity within the de Young Museum; he also accepted responsibility for raising an additional $1.5 million, three-fourths of which would be borne by the City of San Francisco, for the enlargement of the collection.

These were better terms than Brundage could have expected elsewhere. His threats to uproot were mainly bluff, as Alioto might have discovered had he contacted museums in Chicago, Kansas City, or Los Angeles. In political terms, it was not Alioto who entered into the original agreement with Brundage; he could blame his predecessors for the one-sided deal. Still, this was alien terrain for big-city politicians, and in conceding so much, he ensured San Francisco’s title to the entire collection. Nor can the civic-minded intentions of Christopher and Alioto be faulted; the city’s voters were given a chance to approve or reject the bond issue for the museum. It was the failure of city officials to read the fine print that gave a collector renowned for his bullying tactics the legal right to dismember his gift unless he was given his way on every point.

Over time, the Brundage Collection was embedded in layers of later donations in what was renamed the Asian Art Museum, which was detached from the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in Golden Gate Park and moved to a grander new site, facing City Hall. Its new home in the Civic Center is an elegant Renaissance Revival–style building formerly used by the central branch of the city’s public library. In any case, the Bay Area is no longer bereft of Chinese art, and its Asian Art Museum and its associated Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art are now prestigious global destinations for scholars and enthusiasts. Brundage’s six thousand objects proved to be a magnet for another fifteen thousand works.

Appropriately, the highlight of the Brundage trove is a unique and engaging bronze vessel in the shape of a rhinoceros, dating to the Late Shang era in the early eleventh century BCE. It rises nine inches on odd-numbered toes, its hide puckered, its ears erect, and its tail stubby. According to Jay Xu, the director of the Asian Art Museum, circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that Brundage bought the endearing beast in New York from the Shanghai-based dealer J. T. Tai in 1952 for $20,000 (see color plates, figure 10). “That rhino vessel cost me the equivalent of buying five Cadillacs,” he was said to have confided. (In fact, as Xu found, the most expensive Cadillac in the early 1950s was the Eldorado, whose price was $7,750, so “three” seems nearer to the truth.)

Yet in every sense it is fitting that this tough-skinned beast known for its strength and nowadays almost extinct in China should be the emblematic prize of the Brundage Collection. Tests confirm its authenticity, and its inscription, comprising twenty-seven characters, is in quintessential imperial jargon: “On the day dingsi [the fifty-fourth day of the sixty-day cycle], the King inspected the Kui temple. The King bestowed upon Xiaochen Yu [an official title] cowry shells from Kui. It was the time when the King returned from Renfang [an enemy of the dynasty]. It was the King’s fifteenth sacrificial cycle, a day in the rong-ritual cycle.”

In another very different sense, the bronze rhinoceros resonated with its purchaser. Brundage saw himself as belonging to an imperiled breed. “When I’m gone,” he once remarked, “there’s nobody rich enough, thick-skinned enough and smart enough to take my place, and the Games will be in tremendous trouble.” Moreover, the beast’s horn is widely believed to be an aphrodisiac, which helps explain why it has been hunted to near extinction in China. Perhaps ironically appropriate for a serial womanizer who presided over a global harem, as revealed in 1980 (five years after his death) in an article in Sports Illustrated by William Oscar Johnson and a team of researchers in California, Chicago, Geneva, Munich, and Moscow.

“Avery Brundage: The Man Behind the Mask” begins in August 1952 at a lavish banquet in Lausanne, Switzerland, celebrating Brundage’s inauguration as president of the International Olympics Committee, over which he then reigned for two decades. On this occasion, Brundage offered an admonition consistent with the dinner’s Calvinist locale: “We live in a world that is sick, socially, politically and economically. It is sick for only one reason—lack of fair play and good sportsmanship in human relations. We must keep the Olympic movement on Olympic heights of idealism, for it will surely die if it is permitted to descend to more sordid levels.”

The new Olympic president was roundly applauded as he sat down beside his wife, the former Elizabeth Dunlap, the daughter of a Chicago banker, whom he married in 1927. But just five days after this inaugural dinner, his Finnish mistress, Lilian Dresden, age thirty-three, gave birth to their acknowledged son, Gary Toro Dresden, though his paternity was withheld on the birth certificate. This was also the case a year earlier, when their first son, Avery Gregory Dresden, was also born in San Mateo, California. “The fact that Brundage had fathered two sons out of wedlock was only one of a number of startling aspects of his long and remarkable life,” the Sports Illustrated article went on. “The sons were not the rare children of rare indiscretions; Brundage, it turned out, was a philanderer of enormous appetite.”

Much of this was known to his close associates and possibly to the press, but in that era the private lives of politicians and sportsmen were protected by a code of silence so long as appearances were preserved and nothing indiscreet was blurted by the parties involved. What did make news was his remarriage following the death in 1971 of his long-ailing wife, Elizabeth. A year later, his term as Olympic president had expired, and his years of princely travel and sybaritic emoluments were over. “He had a holy fear of being alone then,” according to his financial advisor and confidant, Frederick J. Ruegsegger. Brundage found a new companion, a descendant of German royalty, Mariann Charlotte Katherina Stefanie von Reuss, a lissome blonde whom he had befriended during the Munich Games. In the summer of 1973, Brundage married Princess Reuss; he was eighty-five, she was thirty-six, and a prenuptial agreement specified the obligations and benefits due to each. The newlyweds gravitated between Europe and America, they danced and quarreled, voyaged to the Far East, and settled in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, the twinned Bavarian resort town where the 1936 Winter Olympics were held. It was here that Brundage, already suffering from cataracts, was hospitalized for influenza and died when his heart failed on May 8, 1975. His body was flown to Chicago for burial, and his will bequeathed $6,000 a month each to Princess Reuss and to Ruegsegger, plus $100,000 to the Art Institute of Chicago. His artworks, valued at $1.5 million, were left to San Francisco. Only after his two acknowledged natural sons took legal action did they receive $62,000 in an out-of-court settlement with confidentiality clauses. Nothing was provided for their mother.

So how can one sum up so contradictory a life? Through wit and wile, Avery Brundage proved a true professional in exploiting his amateur reputation on what was verily a field of dreams, to the eventual benefit of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. As to the merits of his collection, a judicious and carefully calibrated assessment was provided by the seasoned scholar Laurence Sickman, who had once been asked to be its curator. This was his evaluation: “The collections of ancient bronzes, ceramics and jades are of the very highest order. . . . Due to an unusual set of circumstances, bronze sacrificial vessels and other objects of the archaic period were on the market in considerable quantities in the 1930’s and early 1940’s. These conditions made it possible to assemble a collection of such magnitude.” Indeed.