Ants and birds do it. So do dogs, various rodents, some species of crabs, and so does homo sapiens. What all these creatures share is an impulse to gather and put aside material things that are not essential to their survival. Studies have confirmed that among humans this impulse may be hereditary and that a child often exhibits the instinctive actions of a collector from its earliest years. “It clings to bits of material, dolls and lead soldiers,” writes Maurice Rheims, once a leading French auctioneer but also an art theorist, “objects are its playthings, offering security as the only tangible matter in its universe.” As a child’s taste develops, he goes on, “so does its spirit of competition as it learns to discern the quality of material objects. This growing aptitude is the child’s first occasion of measuring up to adults.” The collecting instinct can also nurture rebellious rejection, sibling acrimony, and scarring memories that endure for a lifetime (as in the loss of a childhood sled called “Rosebud” in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, a film inspired by the career of William Randolph Hearst, himself an insatiable collector).

Strangely, or maybe not so strangely, the deeper roots of the collecting instinct and its obsessive manifestations still elude comprehensive analysis and explanation. Sigmund Freud, a collector of antiquities, traced the compulsion to unresolved conflicts related to toilet training; his colleague/rival Carl Gustav Jung stressed its link to the collective unconscious. Hence it is the more regrettable that Dr. Arthur M. Sackler, whose collecting career we now examine, did not reflect analytically on the sources of his own collecting instinct. Not only was he a psychiatrist himself, but so were his brothers Mortimer and Raymond. Moreover, in foraging for Chinese art treasures, Arthur Sackler teamed up with Dr. Paul Singer, a Hungarian-born, Vienna-bred psychiatrist, and also a self-taught connoisseur of Oriental art. The Sackler and Singer collections today form the core of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, which is twinned with the Freer Gallery of Art on the National Mall in Washington—a conspicuous tribute to two licensed explorers of the subconscious.

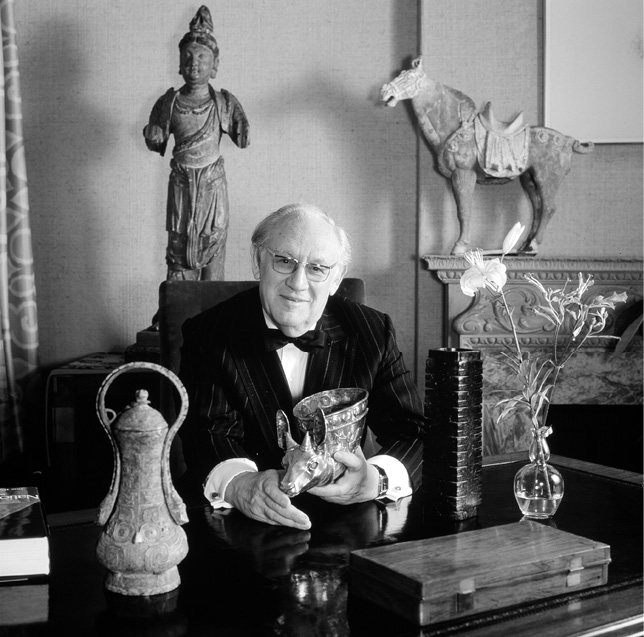

Arthur M. Sackler, psychiatrist and pharmaceutical millionaire, who preferred buying in bulk, here puts his best pieces forward.

Indeed, Dr. Sackler’s career established an important subsidiary variant to the collecting instinct. Not only can the proud possessor gain personal satisfaction in perusing and displaying his precious hoard, but its existence can serve as leverage for obtaining cost-saving storage arrangements—and through the contacts it encourages, lead to brokering retroactive tax deductions in deals with major museums. Finally and not least, through dexterous financial donations to universities and libraries, as well as museums, the collector can give his family name global resonance.

All this Dr. Sackler achieved; he himself is immortalized on the National Mall, while there is also (among others) the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art at Harvard’s Fogg Museum; the Princeton Art Museum Sackler Gallery of Asian Art; the Sackler School of Medicine in Tel Aviv; the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology at Beijing University; the Arthur M. Sackler Science Center at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts; and, at the Metropolitan Museum, not just the Sackler Gallery of Asian Art but also a supersize Sackler Wing enclosing the Egyptian Temple of Dendur, with its adjoining pool, which he and his two brothers helped underwrite.

Still, Arthur M. Sackler was more than a vanity-obsessed self-promoter. Granted, as a collector of artworks, his enthusiasm exceeded his discernment. Princeton’s Wen Fong, while serving as a consultant to the Metropolitan Museum, expressed a common complaint in a 1966 letter to Berkeley’s James Cahill. He termed Sackler difficult to manage and excessively ambitious, adding that he failed to spend sufficient time on research. Yet Sackler himself was aware of his deficiencies, which is why he preferred to buy in bulk. “I collect as a biologist,” he once explained. “To really understand a civilization, a society, you must have a large enough corpus of data. You can’t know twentieth-century art by looking only at Picassos and Henry Moores.”

Creditably, Sackler acknowledged the superior learning of other collectors, to the extent of generously subsidizing the purchases of Dr. Paul Singer, whom he first met at an auction in 1957. His fellow psychiatrist was a micro rather than a macro buyer, a self-taught connoisseur who targeted smaller, eccentric objects passed over by others, which he then squirreled away in his cramped two-bedroom apartment in Summit, New Jersey. Sackler conditioned his subsidy on the understanding that the Singer trove would end up in a Sackler-named institution. And following Singer’s death in 1997, more than six thousand objects valued at $60 million did pass to the Sackler Gallery, more than doubling the size of its then-existing collection. Much of the added hoard consisted of archaeological objects whose interest and rarity were confirmed after careful scrutiny, sustaining their donor’s judgment. Why did Singer collect? “When I see something I like, I feel a visceral excitement,” he explained to Lee Rosenbaum, author of The Complete Guide to Collecting Art. In fact, Dr. Singer, speaking as a psychiatrist, confided to her that collecting is “a highly erotic act, totally akin to lovemaking. . . . Any dealer worth his salt knows there should be no interruption while a collector looks at an object: it is a moment of great intimacy.”

Dr. Paul Singer in his object-crammed New Jersey apartment. As Sackler’s collecting partner, he donated more than 6,000 pieces to the Sackler Gallery.

Besides securing the Singer bequest, Arthur M. Sackler’s other less-than-obvious merit lay in the subsidiary benefits of his own gift. For decades, as James Cahill sharply remarked, “Sackler was famous for dangling his holdings and his money in the faces of great institutions, then shifting his benevolence elsewhere. For some time, there was a ‘Sackler Enclave’ within the storage space of the Far East Department at the Met[ropolitan], presided over by his [Sackler’s] curator; even Met curators needed her permission to get in—a situation unheard of in the history of great museums. The Met ended up with nothing.”

Two comments seem relevant. First, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has no shortage of works suitable for its showcases. Second, and more consequential, since its opening in 1923 as the first federally funded fine arts museum, the Freer Gallery of Art was hamstrung by its donor’s severe conditions: it could neither lend nor borrow. In effect, like Miss Havisham’s mansion in Great Expectations, the Freer was frozen in time. “Had not a second crucial donation been made by Arthur Sackler,” commented the canny reporter Souren Melikian, “leading to the opening of the Sackler Gallery on the same patch along the National Mall—underground, to respect building restrictions—the Freer would have remained a static academic establishment.” Instead, in December 2002, a gala celebration in Washington marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Sackler, presided over by the donor’s British-born widow, Dame Jillian Sackler. Its director, Julian Raby, had this to say about the unusual institutional marriage: “You have two very different buildings with very different characters. One is almost a temple of calm: the Sackler needs to be much more lively, innovative, risky. What I want is a contrast, as opposed to some undifferentiated style.” One million dollars was raised at the gala, and the twinned museums may yet become, in Melikian’s phrase, “the Western world’s capital of Asian art integrated into [a] living culture.”

All of which leads to three unaddressed questions: How did Dr. Arthur M. Sackler acquire the wealth essential to accumulating his collection? Why did he turn to the elusive arts of China, and for what purpose? And are American taxpayers getting fair value from federal support of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Art?

As to the first question, Arthur Sackler, like his younger brothers Mortimer and Raymond, benefited generously from, and contributed to, the dramatic surge in American spending on health care owing to new discoveries, an aging population, public and private health plans, and saturation advertising, especially on television. It is commonly reckoned that America, by a huge margin, leads the world in both per capita and overall expenditure on health care. Additionally, beginning in the 1960s, pharmaceuticals were seen as effective medication for depression and other mental disorders. As investors in the health care industry, the Sackler brothers rode the crest of both the overall and the secondary surge, and in Arthur’s case, a combative spirit helped propel their rise.

All three Sackler boys were born in Brooklyn, New York, where their father, Isaac, had migrated from what is now Ukraine; their mother, Sophie, was born in Poland. Isaac managed a grocery store. Arthur Sackler financed his medical studies at New York University by working at a pharmaceutical advertising agency, later becoming its proprietor. His brothers independently followed his career path.

Sackler by then had honed his bargaining and promotional skills through years of practice in the pharmaceutical trade. He published journals and financed research, and in 1952, when all three were working at Creedmoor, a state psychiatric hospital, the brothers together acquired control of a floundering Greenwich Village–based drug manufacturer, the Purdue Frederick Company. What then evolved into Purdue Pharma produced laxatives (Senokot), eardrops (Cerumenex), antiseptics (Betadine), and after Arthur’s death, a controversial narcotic painkiller, Oxycontin. In his prime, Dr. Arthur Sackler was known positively as an inventive pioneer in biological psychiatry. Along with his brothers as well as other collaborators, he published 140 research papers, primarily dealing with how bodily functions can affect mental illness. This and much else on the affirmative side was noted in Sackler’s 1987 obituary in The New York Times by the veteran arts reporter Grace Glueck. Moreover, as she also writes, “He was the first to use ultrasound for medical diagnosis, and among other pioneering activities, identified histamine as a hormone and called attention to the importance of receptor sites, important in medical theory today.”

All worthy of note, but Dr. Arthur Sackler’s most remarkable nonmedical achievement was then passed over in one short paragraph. At a critical juncture in his collecting career, he managed to outfox the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s directors, senior administrators, curators, and attorneys. In this exacting competition, he holds the winning cup. First, the context. What set Arthur apart from his brothers was his intense focus on Chinese artworks. After studying art history at NYU and New York’s (until recently) tuition-free Cooper Union, Sackler began collecting in the 1940s, his interests ranging from pre-Renaissance and Postimpressionist works to contemporary American art. As Sackler later related, he then happened upon an elegantly designed Ming dynasty table and other stunningly sophisticated objects in a cabinetmaker’s shop. “One wonderful day in 1950, I came upon some Chinese ceramics and Ming furniture. My life has not been the same since. I came to realize that here was an aesthetic not commonly appreciated or understood.”

Within a decade, Dr. Sackler met and teamed up with Dr. Singer, whose expertise he respected and whose art purchases he helped fund from the 1960s onward. Singer’s eye for small, out-of-fashion, but significant works complemented Sackler’s more orthodox taste.

Where Dr. Singer’s instincts proved most prescient was in his purchase of early bronzes and smaller archaeological finds—in his words, “the things that looters leave behind.” High on the list of his prize finds is an array of fifty bronze bells, dating to the early Shang dynasty, around 1200 BCE. They are important not only in their workmanship but also in the sounds they produce, an audible clue to ancient Chinese music. As of our writing, so we learned from J. Keith Wilson, the curator of ancient art at the Sackler, an exhibition featuring the bronze bells is in the planning stage. In any case, the combined collections have beyond doubt raised the global profile of the Freer/Sackler galleries. During the twenty-fifth anniversary in 2012 of the Sackler’s founding, its curators tallied this box score of contributions: Freer, 3,270 pieces; Sackler, 812 pieces; Singer, about 5,000 pieces. The total includes archaeological specimens, Edo-period Japanese prints, and Persian and Indian paintings, all of which found a worthy home in Washington, amounting to a tenfold increase in the holdings of the Sackler Gallery of Art.

No whispering gallery spreads news more promiscuously than the gossip among collectors, dealers, and curators as to who is buying what. Early on, Dr. Arthur Sackler’s resources and purchases came to the attention of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s director, James J. Rorimer. At the time, he was seeking donations to rehabilitate and air-condition the Met’s galleries, not a popular project among would-be name-brand donors. On being approached in 1960, Sackler came up with an ingenious prescription: he promised $150,000 for the renovation of the majestic Great Hall on the second floor, thereafter to be named the Sackler Gallery. Once remodeled, it would display a massive wall painting and monumental sculptures already in the museum’s collection.

In exchange, Sackler sought what the Met’s chief administrator, Joseph Veach Noble, called “nasty” conditions. As recounted by Thomas P. F. Hoving (Rorimer’s successor) in his mischievous 1993 memoir, Making the Mummies Dance, “Sackler would buy the works in question—all masterpieces—at the prices the Met had acquired them back in the twenties, only to give them back to the museum under his name to be designated ‘Gifts of Arthur Sackler.’ The doctor would then take a tax deduction based upon their current values. But that wasn’t the only demand. He asked for a large storeroom inside the museum to house his private collections, an enclave—rent-free—to which only he and his personal curator would have access. Sackler had figured that he would actually make money on the tax loophole he had discovered—his deduction would be far more than the costs of the works, and his donation.”

It was all legal but in Noble’s view “shifty,” and moreover, as Hoving now learned, none of the Chinese art crammed into Sackler’s rent-free enclave was promised to the museum. Under the arrangement he reached with the museum, Sackler obtained a cavernous space for his collection, with the Met paying the costs of insurance, fire protection, and security guards. Sackler chose, and paid the salary of, his collection’s caretaker, Lois Katz, formerly an associate curator at the Brooklyn Museum; he also managed to obtain part-time curatorial privileges for his partner in collecting, Dr. Paul Singer. Very soon the irrepressible Tom Hoving came to like the equally irrepressible Arthur Sackler. In an effort to determine whether the doctor would donate his collection to the Metropolitan, Hoving invited Sackler “for a little chat.” We thus have this timeless snapshot of their encounter:

Within a few minutes after he sat down at the roundtable [I] could tell he liked me and knew also that I could work with him. He was touchy, eccentric, arbitrary—and vulnerable, which made the game much more fascinating. Sackler’s accent was cultivated, clearly manufactured. He seemed to parade his voice as a clear sign of his achievements, but his tone wasn’t phony or affected. He was proud of the way he talked. I liked that. His first words were, “I used to spend marvelous hours here with Jim [Rorimer]. He’d put his army boots up on the desk, and we’d talk for hours of pure scholarship and connoisseurship. Like two ancient Chinese gentlemen-scholars.”

In the days ahead, Tom Hoving did persuade Arthur Sackler to contribute $3.5 million (with the help of his two brothers) for the construction of the enormous new wing that would enclose the Temple of Dendur, which had been rescued from the rising waters of the new Aswan High Dam. But Dr. Sackler would make no promises regarding the eventual destiny of his collection. Meantime, the existence of the collector’s unusual private enclave was for years known only to the museum’s senior officials. In 1978, Professor Sol Channeles, a specialist in criminal law, made public the existence of the Sackler enclave. A muckraking account by Lee Rosenbaum in ARTnews then reported that the New York State attorney general’s office had initiated an inquiry to determine whether the enclave constituted an improper use of the Metropolitan’s space and funds (from the museum’s origins in the 1870s, the Met has relied heavily on New York City for tax benefits and help with housekeeping costs). When asked to comment by Ms. Rosenbaum, then director Philippe de Montebello, President William Macomber, and Board Chairman Douglas Dillon referred all inquiries to the associate counsel, Penelope Bardel, who elliptically said, “It’s not appropriate for people being investigated to talk about the subject of the investigation.”

Very much to the relief of the above-named personages, the state attorney general’s office chided the Metropolitan for its secret deal but proposed no legal action. At the time, the museum’s officers were coping with barbed and angry criticism from Sackler, who was not happy with the presentation and use of the costly Sackler Wing, and he had other grievances. These were itemized by Michael Gross in a gossipy study of the Metropolitan, Rogues’ Gallery (2009). According to the author, Sackler offered a litany of complaints to Tom Hoving. He believed that Ashton Hawkins, then the museum’s legal counselor, had kept him off the Metropolitan’s board, and “he was furious over the way the museum was using the ‘sacred’ Dendur enclosure for parties, calling a recent private dinner for the fashion designer Valentino ‘disgusting’; and he thought a photo of Montebello in a fashion magazine denigrated the museum.”

In 1982, Arthur Sackler announced that he was giving $4 million and the best of his collection to the Smithsonian Institution, which in turn agreed to create the Sackler Gallery of Art on the National Mall. In the end, as earlier noted, the nation indeed benefited, and the Freer/Sackler are today priority destinations for tourists and area residents alike (admission gratis).

And what possessed Dr. Arthur Sackler? As the French aphorist La Bruyère said of collecting, “It is not a pastime but a passion, and often so violent that it is inferior to love and ambition only in the pettiness of its aims.” Or adds the British connoisseur Kenneth Clark: “Why do men and women collect? As well as ask why they fall in love: the reasons are irrational, the motives as mixed.” In the end, however elusive the source of these out-of-body affairs, museums all over the world are filled with their progeny. Who or what has the superior moral claim to their possession is a matter we discuss in our epilogue.