Hem never came back to the store that night. Ursa offered to stay when the last customer left a little before eleven, but otherwise, she didn’t seem concerned that the adults hadn’t come back. “These missions can be so unpredictable,” she said, “but I’m sure you know that. Are you certain you won’t want me to keep you company?”

“No, we’ll be fine. We’re used to this,” Anna lied.

“Why’d you tell her that?” Henry watched through the window as Ursa walked toward the subway. With Aunt Lucinda and everyone gone, it would have been nice to feel like somebody was watching out for them.

“Because,” Anna said, flipping open her notebook, “if Ursa’s here in the morning, she’ll want to know where we’re going and she’ll probably tell us we can’t go because we’re junior members” — Anna rolled her eyes — “and then how are we going to find the Mona Lisa?”

“Did you ever think maybe we shouldn’t go?” José asked.

“José!” Anna’s mouth hung open. “Aren’t you the one who said, ‘The test of any man lies in action’?”

“No, that was Pinhead,” Henry said.

“Pindar. The Greek poet,” José corrected. “Who also said, ‘Learn what you are and be such.’ ”

“And you are …?” Anna raised her eyebrows.

“Kind of afraid of that Catacombs place,” he admitted.

“José, it’s open to the public. How scary can it be?”

José sighed. “Okay. I suppose we’d better try to get some rest.”

That was easier said than done. Henry tossed and turned on his stupid little bench all night. Once, he woke up shivering and thought he felt a breeze, but then he dozed off and it was warmer when he woke up again. It felt like he’d barely slept when somebody started poking him in the shoulder.

“Henry, wake up!”

Henry opened his eyes. “Seriously?” Early morning sun lit Anna’s impatient face. “What time is it?”

“Ten after six. But it’s a long walk, and I want to be there early so we can get in first, because once it fills up with school groups and tourists it’s going to be impossible to get anything done.” She said all this as if she rescued paintings from underground graveyards all the time and knew exactly how to do it.

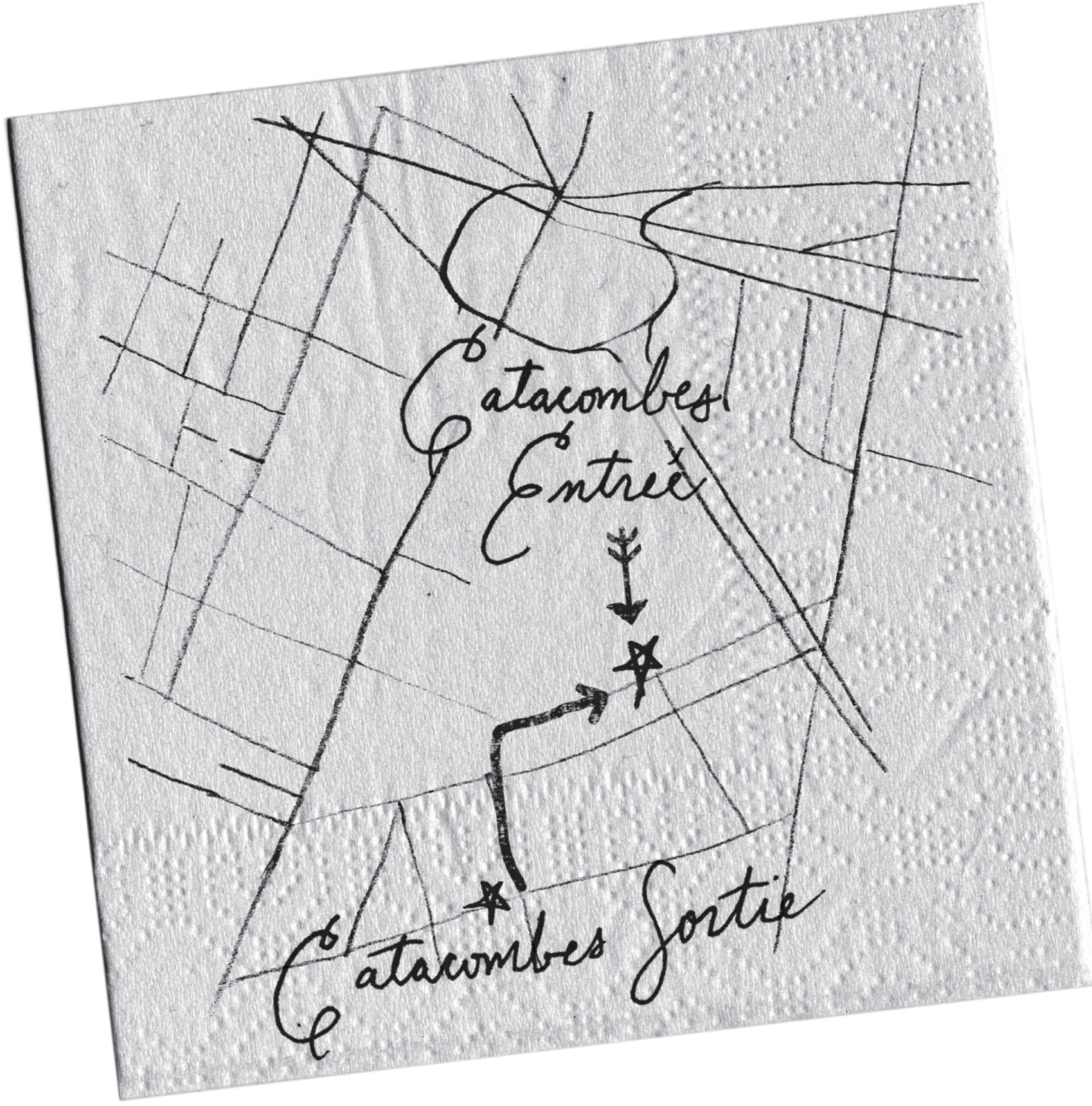

“What’s that?” Anna shoved past Henry, reached for something yellow on the bulletin board behind him, and gasped. “It’s another napkin! With a map! Was this here last night?”

“I don’t think so.” Henry had been totally wiped out, though. Would he have noticed? “Maybe.”

“Is it one of Hem’s?” José came into the room. The back of his hair was sticking up. “Given the circumstances, I’m not sure we want to put too much faith in that.”

“No. His maps are amazing, and this one is all scribbled. But this is — ohmygosh …” She took the map to the window where there was more light. “It’s the Catacombs. The exit is marked … and then there’s like a path traced to someplace else!”

“Where?” Henry stretched and walked over to the window.

“Wherever this is.” Anna pointed to the map. A shaky blue pen line went from a star marked Catacombes Sortie up the street, around a couple turns, and to another star with a big barbed arrow pointing south.

“You guys, I bet this is where they are! Our parents! This must mean … I bet they can’t recover the painting so we have to do it and then take it to them and then …”

“And then we’ll all live happily ever after?” Henry scoffed. “Dude, we have no clue who left this here.”

“That’s true,” Anna admitted, studying the map. “And I don’t recognize the writing. Do you, guys?”

“No,” Henry blurted, but as soon as the word was out of his mouth, he realized it was wrong. “Actually, wait …” He reached for the napkin. “That’s totally how Aunt Lucinda’s makes her Cs. But there’s no way she’d come here to leave a map and not talk to me. Not with everything going on.”

“Maybe someone else delivered it,” José said.

“Who? And when?” Henry handed the napkin back to Anna and thought about waking up in the cold. Could Gilbert or someone have climbed in the window and left the map without him noticing? It was too creepy to say out loud.

“It doesn’t matter,” Anna said, tucking the napkin into her pocket. “We know what we need to do.”

Henry had a bad feeling in his stomach, the way he felt when he got to level twenty-four on his Storm the Castle game. He knew he was going to die when the knights started shooting flaming arrows, but he always tried to run through them anyway. “Fine,” he said, even though he could already hear electronic doom music in his head. “Let’s go.”

They got to the Catacombs entrance a little before eight. Nobody was around except two old ladies sitting on a bench. One had enormous sunglasses that made her look like a giant, white-haired bug. The other was rummaging through a purple fanny pack that seemed to have a whole suitcase worth of junk crammed into it.

“They open at ten. The line starts behind us.” One of the old ladies said, looking at the kids over her bug-eye shades.

“No problem,” Anna said, and stepped back a little, motioning for Henry and José to come closer. “It’s good that we’re early,” she whispered. “We need to talk. I’ve been thinking that we need a code name for the painting. We can’t be chatting about this in public using her real name.”

“What do you want to call her?” Henry asked. “M.L.?”

Anna shook her head. “Too obvious.”

“We could call her … umm …” Henry thought about the girls in his grade. “Emma? Brittany?”

“Brittany? That’s totally undignified.”

“Actually,” José said thoughtfully, “it’s perfect. No one will associate a modern name with a priceless work of art.”

“That’s a good point.” Anna looked annoyed, but she nodded. “So when we find … Brittany … we need a way to sneak her out of the museum. Back in Boston, I heard my mom say a lot of the stolen paintings had been sliced out of their frames. If that happened to Brittany, I’m guessing the canvas will be rolled up. I brought my backpack, but the sign up there says they have the right to search bags. To make sure people don’t steal bones.”

“In level fourteen of my Super-Heist game, one of the guys sneaks like a hundred thousand dollars out of a bank in his pants,” Henry said. “He duct-tapes the money to his legs.”

“That might actually work.” Anna, who was wearing a long shirt with leggings, looked at José, whose jeans were really skinny at the bottom. Then they both looked at Henry.

“No way.” He tugged his baggy jeans up higher. He should have kept his mouth shut. “I can’t hide the Mona Lisa in my pants!”

“You mean Brittany!” Anna whispered, nodding toward the old ladies on the bench and gesturing to the line behind them, which already had another few dozen people in it.

“Okay, Brittany. But I can’t. That’s like totally disrespectful. Aunt Lucinda would kill me.”

“Henry …” Anna leaned in close. “If we find her, we’ll be saving what may be the most famous piece of art in the world. Don’t you think we should do whatever it takes?”

“Aw, man …” Henry wished he’d listened to his dad and gotten some school pants that weren’t so droopy. “I guess. But I don’t have any duct tape.”

Anna frowned. “What about string or something?”

Henry checked his pockets and pulled out his SuperGamePrism charger cord. “This is all I got.”

Anna nodded. “That should work.”

There wasn’t any more planning to do, so Henry counted people as the line grew. He watched a pigeon trying to get a crumb under the old ladies’ bench. Every time it got close, the fanny pack lady would stomp her foot, and it would scurry away again.

Henry was about to go crawl down there, get the crumb, and throw it to the dumb bird when Anna grabbed his arm and pulled him behind the bench, along with José. “They’re here!” She pointed to the big metal door, where the two Serpentine Prince guys from the Louvre were arguing with a Catacombs worker.

“They’re trying to get in ahead of everyone,” Anna whispered.

“Doesn’t look like they’re having much luck,” José said.

The worker kept shaking his head, pointing to the back of the line, which stretched halfway around the block now. The sumo wrestler put a hand in his pocket, and for a second, Henry thought he’d pull a gun or a knife or something, but then he slipped out a pocket watch, sighed, and motioned for the skinny guy to come with him to the end of the line.

“Dude, I can’t believe they didn’t force their way in,” Henry said. “What kind of bad guys are they?”

“They probably didn’t want to make a scene,” Anna said as the worker started unlocking the door to let people inside. “That’s lucky for us, but we’ll need to be fast. We have to find what we’re looking for before those guys get inside.” Anna paid for the tickets, and they followed the old ladies, one slow step at a time, down a spiral staircase that never seemed to end.

Henry looked up at José, descending behind him. “How far down does this go?”

José unfolded the brochure he’d grabbed at the entrance. “One hundred thirty steps. Twenty meters.”

Finally, they reached the bottom, and the old ladies started shuffling their way down a narrow stone tunnel.

The one with the big sunglasses perched them on top of her head and gave a loud sniff. “Musty down here, isn’t it, Bertha?”

“Excuse me,” Anna said as they squeezed past the women and hurried along the passage. The air did feel heavy and damp. The ceilings were getting lower, and Henry had to duck to get through one of the doorways.

“We must be in the remains of those old quarries Hem was talking about,” José said as they hurried past the interpretive signs along the empty halls. Stone pillars seemed to be holding up the ceiling. Henry hoped they were solid.

They turned, and the hallway opened up into a big room with an elaborate sculpture of a mansion carved right into one of the stone walls.

“Whoa …” José paused and read the panel next to it. “This says the artist was a quarry inspector. It’s a model of some fortress where he fought.”

Henry stared at the intricate carving. The building’s tiny front steps had been carefully chiseled, one by one. “This must have taken forever. Who’d want to spend all that time down here?”

“Not me,” Anna said. “Come on.” They followed a shadowy hallway into another dimly lit open space. There were no stone fortresses here, but the far side of the room had a doorway with words engraved above it:

ARRÈTE! C’EST ICI L’EMPIRE DE LA MORT

“Oh, I just saw this….” José flipped through his brochure. “It means ‘Stop! This is the empire of death.’ ”

Worst. Welcome sign. Ever, Henry thought. But he followed Anna through the doorway.

And found himself facing a solid wall of bones.

He took a step forward. “This is … this is …” The pictures online had been creepy enough, but this room was overflowing with real-life, in-your-face awfulness. Even the air felt full of death. Henry could barely breathe anymore.

“There’s that quote,” José whispered.

On a smooth stone slab, surrounded by bones, was the poem from the napkin.

Ils furent ce que nous sommes,

Poussière, jouet du vent;

Fragiles comme des hommes.

Faibles comme le néant!

Henry remembered the translation.

They were what we are …

Alive, once. But now their bones were in heaps, and nobody even knew their names.

Henry looked at José, who was staring at the stone inscription. The wall of bones had even stopped Anna in her tracks. She was kneeling, staring into the eye sockets of a yellowed skull, and for once, she didn’t have anything to say.

Something dripped on the back of Henry’s neck, and he looked up. The ceiling was full of stubby, slimy-looking stalactites like the ones he’d seen on his class field trip to Howe Caverns in second grade. Henry wiped his neck with his hand. He didn’t even want to think about what was in this water. “Come on, you guys. Let’s get out of here.”

“Yeah …” Anna said, finally breaking eye contact with the skull. She stood up, brushed off her knees and blinked a few times, fast. Henry could tell she was trying to get her brave back, but that wasn’t easy down here. “We need to watch for the crossbones. Remember the photo on that lady’s website?” Anna held up her pointer fingers, crossed like an X.

José nodded. “ ‘The spot marked with imperfect X.’ ” And they started down the hallway of bones.

At first, Henry looked all over for the imperfect X. But it felt like the walls were getting closer, pressing against his chest. He took a deep breath — just keep walking — and stared straight ahead at the back of José’s messy hair. But even though he tried not to look at the bones, it felt as if the bones were looking at him.

A light-colored stone cross stood out from one of the walls, shored up by bones on every side. Whoever arranged them had made patterns. A wall of leg bones, all stacked tight, with a border of skulls along the bottom and more arranged in an arch over the cross.

Henry swallowed hard. Every one of those skulls belonged to a person who used to be alive. Someone with stories and a life and a family. Maybe a baby sister like his.

José kept folding and unfolding his brochure, holding on as if it were a life raft to keep him from sinking in the heaps of bones.

“Let’s go.” Henry tried to make his voice sound brave, but he really wanted to get out of there. How long could these tunnels go on?

They started walking again. Every time they turned a corner, Henry hoped for a staircase back to the street. But the path never even sloped up. Every narrow hallway led to another room of awful architecture. There were pillars of bones and columns of bones and pedestals of bones. Henry looked down at the floor and took a deep breath. It felt like there wasn’t enough oxygen down here … as if the skulls were sucking it all up.

“You guys, look!” Anna called from behind him, and Henry turned around.

He’d walked right past it — a corner of bones like all the others, but this one had the skull and crossbones design, repeated in a neat row.

“There it is,” José whispered. He pointed to the last design, half missing — just a skull above a single diagonal leg bone. “Imperfect X.”