35 Color Vision

35–1 The human eye

The phenomenon of colors depends partly on the physical world. We

discuss the colors of soap films and so on as being produced by

interference. But also, of course, it depends on the eye, or what

happens behind the eye, in the brain. Physics characterizes the light

that enters the eye, but after that, our sensations are the result of

photochemical-neural processes and psychological responses.

There are many interesting phenomena associated with vision which

involve a mixture of physical phenomena and physiological processes,

and the full appreciation of natural phenomena, as we see them, must

go beyond physics in the usual sense. We make no apologies for making

these excursions into other fields, because the separation of fields,

as we have emphasized, is merely a human convenience, and an unnatural

thing. Nature is not interested in our separations, and many of the

interesting phenomena bridge the gaps between fields.

In Chapter 3 we have already discussed the relation of

physics to the other sciences in general terms, but now we are going

to look in some detail at a specific field in which physics and other

sciences are very, very closely interrelated. That area is

vision. In particular, we shall discuss color vision. In

the present chapter we shall discuss mainly the observable phenomena

of human vision, and in the next chapter we shall consider the

physiological aspects of vision, both in man and in other animals.

It all begins with the eye; so, in order to understand what phenomena

we see, some knowledge of the eye is required. In the next chapter we

shall discuss in some detail how the various parts of the eye work,

and how they are interconnected with the nervous system. For the

present, we shall describe only briefly how the eye functions

(Fig. 35–1).

Fig. 35–1. The eye.

Light enters the eye through the cornea; we have

already discussed how it is bent and is imaged on a layer called the

retina in the back of the eye, so that different

parts of the retina receive light from different parts of

the visual field outside. The retina is not absolutely

uniform: there is a place, a spot, in the center of our field of view

which we use when we are trying to see things very carefully, and at

which we have the greatest acuity of vision; it is called the

fovea or macula. The side parts of the eye,

as we can immediately appreciate from our experience in looking at

things, are not as effective for seeing detail as is the center of the

eye. There is also a spot in the retina where the nerves

carrying all the information run out; that is a blind spot. There is no

sensitive part of the retina here, and it is possible to

demonstrate that if we close, say, the left eye and look straight at

something, and then move a finger or another small object slowly out of

the field of view it suddenly disappears somewhere. The only practical

use of this fact that we know of is that some physiologist became quite

a favorite in the court of a king of France by pointing this out to him;

in the boring sessions that he had with his courtiers, the king could

amuse himself by “cutting off their heads” by looking at one and

watching another’s head disappear.

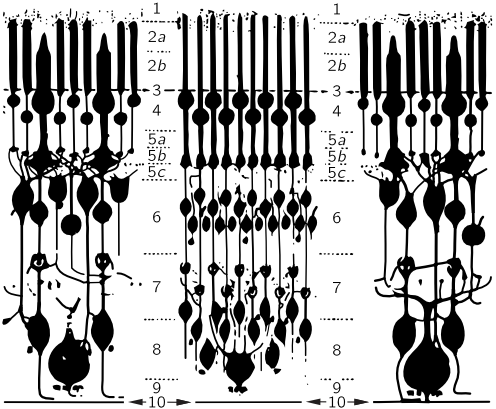

Fig. 35–2. The structure of the retina. (Light enters from below.)

Figure 35–2 shows a magnified view of the inside of the

retina in somewhat schematic form. In different parts of the

retina

there are different kinds of structures. The objects that occur more

densely near the periphery of the retina are called

rods. Closer to the fovea, we find, besides these

rod cells, also cone cells. We shall describe the structure of

these cells later. As we get close to the fovea, the

number of cones increases, and in the fovea itself there

are in fact nothing but cone cells, packed very tightly, so tightly

that the cone cells are much finer, or narrower here than anywhere

else. So we must appreciate that we see with the cones right in the

middle of the field of view, but as we go to the periphery we have the

other cells, the rods. Now the interesting thing is that in the retina

each of the cells which is sensitive to light is not connected by a

fiber directly to the optic nerve, but is connected

to many other cells, which are themselves connected to each other. There

are several kinds of cells: there are cells that carry the information

toward the optic nerve, but there are others that are

mainly interconnected “horizontally.” There are essentially four kinds

of cells, but we shall not go into these details now. The main thing we

emphasize is that the light signal is already being “thought about.”

That is to say, the information from the various cells does not

immediately go to the brain, spot for spot, but in the retina a certain

amount of the information has already been digested, by a combining of

the information from several visual receptors. It is important to

understand that some brain-function phenomena occur in the eye itself.

35–2 Color depends on intensity

One of the most striking phenomena of vision is the dark adaptation of

the eye. If we go into the dark from a brightly lighted room, we

cannot see very well for a while, but gradually things become more and

more apparent, and eventually we can see something where we could see

nothing before. If the intensity of the light is very low, the things

that we see have no color. It is known that this dark-adapted

vision is almost entirely due to the rods, while the vision in bright

light is due to the cones. As a result, there are a number of

phenomena that we can easily appreciate because of this transfer of

function from the cones and rods together, to just the rods.

There are many situations in which, if the light intensity were

stronger, we could see color, and we would find these things quite

beautiful. One example is that through a telescope we nearly always see

“black and white” images of faint nebulae, but W. C.

Miller of the Mt. Wilson and

Palomar Observatories had the patience to make color pictures of

some of these objects. Nobody has ever really seen these colors with the

eye, but they are not artificial colors, it is merely that the light

intensity is not strong enough for the cones in our eye to see them.

Among the more spectacular such objects are the ring nebula and the Crab

nebula. The former shows a beautiful blue inner part, with a bright red

outer halo, and the latter shows a general bluish haze permeated by

bright red-orange filaments.

In the bright light, apparently, the rods are at very low sensitivity

but, in the dark, as time goes on they pick up their ability to see

light. The variations in light intensity for which one can adapt is

over a million to one. Nature does not do all this with just one kind

of cell, but she passes her job from bright-light-seeing cells, the

color-seeing cells, the cones, to low-intensity, dark-adapted cells,

the rods. Among the interesting consequences of this shift is, first,

that there is no color, and second, that there is a difference in the

relative brightness of differently colored objects. It turns out that

the rods see better toward the blue than the cones do, and the cones

can see, for example, deep red light, while the rods find that

absolutely impossible to see. So red light is black so far as the rods

are concerned. Thus two pieces of colored paper, say blue and red, in

which the red might be even brighter than the blue in good light,

will, in the dark, appear completely reversed. It is a very striking

effect. If we are in the dark and can find a magazine or something

that has colors and, before we know for sure what the colors are, we

judge the lighter and darker areas, and if we then carry the magazine

into the light, we may see this very remarkable shift between which

was the brightest color and which was not. The phenomenon is called

the Purkinje effect.

Fig. 35–3. The spectral sensitivity of the eye. Dashed curve, rods;

solid curve, cones.

In Fig. 35–3, the dashed curve represents the

sensitivity of the eye in the dark, i.e., using the rods, while the

solid curve represents it in the light. We see that the peak

sensitivity of the rods is in the green region and that of the cones

is more in the yellow region. If there is a red-colored page (red is

about 650 mμ) we can see it if it is brightly lighted, but in

the dark it is almost invisible.

Another effect of the fact that rods take over in the dark, and that

there are no rods in the fovea, is that when we look

straight at something in the dark, our vision is not quite as acute as

when we look to one side. A faint star or nebula can sometimes be seen

better by looking a little to one side than directly at it, because we

do not have sensitive rods in the middle of the fovea.

Another interesting effect of the fact that the number of cones

decreases as we go farther to the side of the field of view is that

even in a bright light color disappears as the object goes far to one

side. The way to test that is to look in some particular fixed

direction, let a friend walk in from one side with colored cards, and

try to decide what color they are before they are right in front of

you. One finds that he can see that the cards are there long before he

can determine the color. When doing this, it is advisable to come in

from the side opposite the blind spot, because it is otherwise rather

confusing to almost see the color, then not see anything, then to see

the color again.

Another interesting phenomenon is that the periphery of the retina is

very sensitive to motion. Although we cannot see very well from the

corner of our eye, if a little bug moves and we do not expect anything

to be moving over there, we are immediately sensitive to it. We are

all “wired up” to look for something jiggling to the side of the

field.

35–3 Measuring the color sensation

Now we go to the cone vision, to the brighter vision, and we come to

the question which is most characteristic of cone vision, and that is

color. As we know, white light can be split by a prism into a whole

spectrum of wavelengths which appear to us to have different colors;

that is what colors are, of course: appearances. Any source of light

can be analyzed by a grating or a prism, and one can determine the

spectral distribution, i.e., the “amount” of each wavelength. A

certain light may have a lot of blue, considerable red, very little

yellow, and so on. That is all very precise in the sense of physics,

but the question is, what color will it appear to be? It is

evident that the different colors depend somehow upon the spectral

distribution of the light, but the problem is to find what

characteristics of the spectral distribution produce the various

sensations. For example, what do we have to do to get a green color?

We all know that we can simply take a piece of the spectrum which is

green. But is that the only way to get green, or orange, or any

other color?

Is there more than one spectral distribution which produces the same

apparent visual effect? The answer is, definitely yes. There is

a very limited number of visual effects, in fact just a

three-dimensional manifold of them, as we shall shortly see, but there

is an infinite number of different curves that we can draw for the

light that comes from different sources. Now the question we have to

discuss is, under what conditions do different distributions of light

appear as exactly the same color to the eye?

The most powerful psycho-physical technique in color judgment is to

use the eye as a null instrument. That is, we do not try to

define what constitutes a green sensation, or to measure in what

circumstances we get a green sensation, because it turns out that this

is extremely complicated. Instead, we study the conditions under which

two stimuli are indistinguishable. Then we do not have to

decide whether two people see the same sensation in different

circumstances, but only whether, if for one person two sensations are

the same, they are also the same for another. We do not have to decide

whether, when one sees something green, what it feels like inside is

the same as what it feels like inside someone else when he sees

something green; we do not know anything about that.

To illustrate the possibilities, we may use a series of four projector

lamps which have filters on them, and whose brightnesses are

continuously adjustable over a wide range: one has a red filter and

makes a spot of red light on the screen, the next one has a green

filter and makes a green spot, the third one has a blue filter, and

the fourth one is a white circle with a black spot in the middle of

it. Now if we turn on some red light, and next to it put some green,

we see that in the area of overlap it produces a sensation which is

not what we call reddish green, but a new color, yellow in this

particular case. By changing the proportions of the red and the green,

we can go through various shades of orange and so forth. If we have

set it for a certain yellow, we can also obtain that same yellow, not

by mixing these two colors but by mixing some other ones, perhaps a

yellow filter with white light, or something like that, to get the

same sensation. In other words, it is possible to make various colors

in more than one way by mixing the lights from various filters.

What we have just discovered may be expressed analytically as

follows. A particular yellow, for example, can be represented by a

certain symbol Y, which is the “sum” of certain amounts of

red-filtered light (R) and green-filtered light (G). By using two

numbers, say r and g, to describe how bright the R and G are,

we can write a formula for this yellow:

(35.1)

The question is, can we make all the different colors by adding

together two or three lights of different, fixed colors? Let us see

what can be done in that connection. We certainly cannot get all the

different colors by mixing only red and green, because, for instance,

blue never appears in such a mixture. However, by putting in some blue

the central region, where all three spots overlap, may be made to

appear to be a fairly nice white. By mixing the various colors and

looking at this central region, we find that we can get a considerable

range of colors in that region by changing the proportions, and so it

is not impossible that all the colors can be made by mixing

these three colored lights. We shall discuss to what extent this is

true; it is in fact essentially correct, and we shall shortly see how

to define the proposition better.

In order to illustrate our point, we move the spots on the screen so

that they all fall on top of each other, and then we try to match a

particular color which appears in the annular ring made by the fourth

lamp. What we once thought was “white” coming from the fourth lamp

now appears yellowish. We may try to match that by adjusting the red

and green and blue as best we can by a kind of trial and error, and we

find that we can approach rather closely this particular shade of

“cream” color. So it is not hard to believe that we can make all

colors. We shall try to make yellow in a moment, but before we do

that, there is one color that might be very hard to make. People who

give lectures on color make all the “bright” colors, but they never

make brown, and it is hard to recall ever having seen brown

light. As a matter of fact, this color is never used for any stage

effect, one never sees a spotlight with brown light; so we think it

might be impossible to make brown. In order to find out whether it is

possible to make brown, we point out that brown light is merely

something that we are not used to seeing without its background. As a

matter of fact, we can make it by mixing some red and yellow. To prove

that we are looking at brown light, we merely increase the brightness

of the annular background against which we see the very same light,

and we see that that is, in fact, what we call brown! Brown is always

a dark color next to a lighter background. We can easily change the

character of the brown. For example, if we take some green out we get

a reddish brown, apparently a chocolaty reddish brown, and if we put

more green into it, in proportion, we get that horrible color which

all the uniforms of the Army are made of, but the light from that

color is not so horrible by itself; it is of yellowish green, but seen

against a light background.

Now we put a yellow filter in front of the fourth light and try to

match that. (The intensity must of course be within the range of the

various lamps; we cannot match something which is too bright, because

we do not have enough power in the lamp.) But we can match the

yellow; we use a green and red mixture, and put in a touch of blue to

make it even more perfect. Perhaps we are ready to believe that, under

good conditions, we can make a perfect match of any given color.

Now let us discuss the laws of color mixture. In the first place, we

found that different spectral distributions can produce the same

color; next, we saw that “any” color can be made by adding together

three special colors, red, blue, and green. The most interesting

feature of color mixing is this: if we have a certain light, which we

may call X, and if it appears indistinguishable from Y, to the eye

(it may be a different spectral distribution, but it appears

indistinguishable), we call these colors “equal,” in the sense that

the eye sees them as equal, and we write

(35.2)

Here is one of the great laws of color: if two spectral distributions

are indistinguishable, and we add to each one a certain light,

say Z (if we write X+Z, this means that we shine both lights on

the same patch), and then we take Y and add the same amount of the

same other light, Z, the new mixtures are also

indistinguishable:

(35.3)

We have just matched our yellow; if we now shine pink light on the

whole thing, it will still match. So adding any other light to the

matched lights leaves a match. In other words, we can summarize all

these color phenomena by saying that once we have a match between two

colored lights, seen next to each other in the same circumstances,

then this match will remain, and one light can be substituted for the

other light in any other color mixing situation. In fact, it turns

out, and it is very important and interesting, that this matching of

the color of lights is not dependent upon the characteristics of the

eye at the moment of observation: we know that if we look for a long

time at a bright red surface, or a bright red light, and then look at

a white paper, it looks greenish, and other colors are also distorted

by our having looked so long at the bright red. If we now have a match

between, say, two yellows, and we look at them and make them match,

then we look at a bright red surface for a long time, and then turn

back to the yellow, it may not look yellow any more; I do not know

what color it will look, but it will not look yellow. Nevertheless

the yellows will still look matched, and so, as the eye adapts

to various levels of intensity, the color match still works, with the

obvious exception of when we go into the region where the intensity of

the light gets so low that we have shifted from

cones to

rods; then the color

match is no longer a color match, because we are using a different

system.

The second principle of color mixing of lights is this: any

color at all can be made from three different colors, in our case,

red, green, and blue lights. By suitably mixing the three together we

can make anything at all, as we demonstrated with our two

examples. Further, these laws are very interesting mathematically. For

those who are interested in the mathematics of the thing, it turns out

as follows. Suppose that we take our three colors, which were red,

green, and blue, but label them A, B, and C, and call them our

primary colors. Then any color could be made by certain amounts

of these three: say an amount a of color A, an amount b of

color B, and an amount c of color C makes X:

(35.4)

Now suppose another color Y is made from the same three colors:

(35.5)

Then it turns out that the mixture of the two lights (it is one of the

consequences of the laws that we have already mentioned) is obtained

by taking the sum of the components of X and Y:

(35.6)

It is just like the mathematics of the addition of vectors, where

(a,b,c) are the components of one vector, and (a′,b′,c′) are those

of another vector, and the new light Z is then the “sum” of the

vectors. This subject has always appealed to physicists and

mathematicians. In fact, Schrödinger wrote a wonderful

paper on color vision in which he developed this theory of vector

analysis as applied to the mixing of colors.1

Now a question is, what are the correct primary colors to use? There

is no such thing as “the” correct primary colors for the mixing of

lights. There may be, for practical purposes, three paints that are

more useful than others for getting a greater variety of mixed

pigments, but we are not discussing that matter now. Any three

differently colored lights whatsoever2 can always

be mixed in the correct proportion to produce any color

whatsoever. Can we demonstrate this fantastic fact? Instead of using

red, green, and blue, let us use red, blue, and yellow in our

projector. Can we use red, blue, and yellow to make, say, green?

By mixing these three colors in various proportions, we get quite an

array of different colors, ranging over quite a spectrum. But as a

matter of fact, after a lot of trial and error, we find that nothing

ever looks like green. The question is, can we make green? The

answer is yes. How? By projecting some red onto the green, then

we can make a match with a certain mixture of yellow and blue! So we

have matched them, except that we had to cheat by putting the red on

the other side. But since we have some mathematical sophistication, we

can appreciate that what we really showed was not that X could

always be made, say, of red, blue, and yellow, but by putting the red

on the other side we found that red plus X could be made out of blue

and yellow. Putting it on the other side of the equation, we can

interpret that as a negative amount, so if we will allow that

the coefficients in equations like (35.4) can be both

positive and negative, and if we interpret negative amounts to mean

that we have to add those to the other side, then any

color can be matched by any three, and there is no such thing as

“the” fundamental primaries.

We may ask whether there are three colors that come only with positive

amounts for all mixings. The answer is no. Every set of three

primaries requires negative amounts for some colors, and therefore

there is no unique way to define a primary. In elementary books they

are said to be red, green, and blue, but that is merely because with

these a wider range of colors is available without minus signs

for some of the combinations.

35–4 The chromaticity diagram

Fig. 35–4. The standard chromaticity diagram.

Now let us discuss the combination of colors on a mathematical level

as a geometrical proposition. If any one color is represented by

Eq. (35.4), we can plot it as a vector in space by plotting

along three axes the amounts a, b, and c, and then a certain color

is a point. If another color is a′, b′, c′, that color is located

somewhere else. The sum of the two, as we know, is the color which comes

from adding these as vectors. We can simplify this diagram and represent

everything on a plane by the following observation: if we had a certain

color light, and merely doubled a and b and c, that is, if we make

them all stronger in the same ratio, it is the same color, but brighter.

So if we agree to reduce everything to the same light intensity,

then we can project everything onto a plane, and this has been done in

Fig. 35–4. It follows that any color obtained by mixing a

given two in some proportion will lie somewhere on a line drawn between

the two points. For instance, a fifty-fifty mixture would appear halfway

between them, and 1/4 of one and 3/4 of the other would appear

1/4 of the way from one point to the other, and so on. If we use a blue and

a green and a red, as primaries, we see that all the colors that we can

make with positive coefficients are inside the dotted triangle, which

contains almost all of the colors that we can ever see, because all the

colors that we can ever see are enclosed in the oddly shaped area

bounded by the curve. Where did this area come from? Once somebody made

a very careful match of all the colors that we can see against three

special ones. But we do not have to check all colors that we can

see, we only have to check the pure spectral colors, the lines of the

spectrum. Any light can be considered as a sum of various positive

amounts of various pure spectral colors—pure from the physical

standpoint. A given light will have a certain amount of red, yellow,

blue, and so on—spectral colors. So if we know how much of each of our

three chosen primaries is needed to make each of these pure components,

we can calculate how much of each is needed to make our given color.

So, if we find out what the color coefficients of all the

spectral colors are for any given three primary colors, then we can work

out the whole color mixing table.

Fig. 35–5. The color coefficients of pure spectral colors in terms of a

certain set of standard primary colors.

An example of such experimental results for mixing three lights

together is given in Fig. 35–5. This figure shows the

amount of each of three different particular primaries, red, green and

blue, which is required to make each of the spectral colors. Red is at

the left end of the spectrum, yellow is next, and so on, all the way

to blue. Notice that at some points minus signs are necessary. It is

from such data that it is possible to locate the position of all of

the colors on a chart, where the x- and the y-coordinates are

related to the amounts of the different primaries that are used. That

is the way that the curved boundary line has been found. It is the

locus of the pure spectral colors. Now any other color can be made by

adding spectral lines, of course, and so we find that anything that

can be produced by connecting one part of this curve to another is a

color that is available in nature. The straight line connects the

extreme violet end of the spectrum with the extreme red end. It is the

locus of the purples. Inside the boundary are colors that can be made

with lights, and outside it are colors that cannot be made with

lights, and nobody has ever seen them (except, possibly, in

after-images!).

35–5 The mechanism of color vision

Now the next aspect of the matter is the question, why do colors

behave in this way? The simplest theory, proposed by

Young and

Helmholtz, supposes that in

the eye there are three different pigments which receive the light and

that these have different absorption spectra, so that one pigment

absorbs strongly, say, in the red, another absorbs strongly in the blue,

another absorbs in the green. Then when we shine a light on them we will

get different amounts of absorptions in the three regions, and these

three pieces of information are somehow maneuvered in the brain or in

the eye, or somewhere, to decide what the color is. It is easy to

demonstrate that all of the rules of color mixing would be a consequence

of this proposition. There has been considerable debate about the thing

because the next problem, of course, is to find the absorption

characteristics of each of the three pigments. It turns out,

unfortunately, that because we can transform the color coordinates in

any manner we want to, we can only find all kinds of linear combinations

of absorption curves by the color-mixing experiments, but not the curves

for the individual pigments. People have tried in various ways to obtain

a specific curve which does describe some particular physical property

of the eye. One such curve is called a brightness curve,

demonstrated in Fig. 35–3. In this figure are two curves,

one for eyes in the dark, the other for eyes in the light; the latter is

the cone brightness curve. This is measured by finding what is the

smallest amount of colored light we need in order to be able to just see

it. This measures how sensitive the eye is in different spectral

regions. There is another very interesting way to measure this. If we

take two colors and make them appear in an area, by flickering back and

forth from one to the other, we see a flicker if the frequency is too

low. However, as the frequency increases, the flicker will ultimately

disappear at a certain frequency that depends on the brightness of the

light, let us say at 16 repetitions per second. Now if we adjust the

brightness or the intensity of one color against the other, there comes

an intensity where the flicker at 16 cycles disappears. To get flicker

with the brightness so adjusted, we have to go to a much lower frequency

in order to see a flicker of the color. So, we get what we call a

flicker of the brightness at a higher frequency and, at a lower

frequency, a flicker of the color. It is possible to match two colors

for “equal brightness” by this flicker technique. The results are

almost, but not exactly, the same as those obtained by measuring the

threshold sensitivity of the eye for seeing weak light by the

cones. Most workers use the

flicker system as a definition of the brightness curve.

Now, if there are three color-sensitive pigments in the eye, the

problem is to determine the shape of the absorption spectrum of each

one. How? We know there are people who are color blind—eight percent

of the male population, and one-half of one percent of the female

population. Most of the people who are color blind or abnormal in

color vision have a different degree of sensitivity than others to a

variation of color, but they still need three colors to

match. However, there are some who are called dichromats, for

whom any color can be matched using only two primary

colors. The obvious suggestion, then, is to say that they are missing

one of the three pigments. If we can find three kinds of color-blind

dichromats who have different color-mixing rules, one kind should be

missing the red, another the green, and another the

blue pigmentation. By measuring all these types we can

determine the three curves! It turns out that there are three

types of dichromatic color blindness; there are two common types and a

third very rare type, and from these three it has been possible to

deduce the pigment absorption spectra.

Fig. 35–6. Loci of colors confused by deuteranopes.

Figure 35–6 shows the color mixing of a particular type of

color-blind person called a deuteranope. For him, the loci of constant

colors are not points, but certain lines, along each of which the color

appears to him to be the same. If the theory that he is missing one of

the three pieces of information is right, all these lines should

intersect at a point. If we carefully measure on this graph, they

do intersect perfectly. Obviously, therefore, this has been made

by a mathematician and does not represent real data! As a matter of

fact, if we look at the latest paper with real data, it turns out that

in the graph of Fig. 35–6, the point of focus of all the

lines is not exactly at the right place. Using the lines in the above

figure, we cannot find reasonable spectra; we need negative and positive

absorptions in different regions. But using the new data of

Yustova, it turns out that

each of the absorption curves is everywhere positive.

Fig. 35–7. Loci of colors confused by protanopes.

Figure 35–7 shows a different kind of color blindness, that

of the protanope, which has a focus near the red end of the boundary

curve. Yustova gets

approximately the same position in this case. Using the three different

kinds of color blindness, the three pigment response curves have finally

been determined, and are shown in Fig. 35–8. Finally?

Perhaps. There is a question as to whether the three-pigment idea

is right, whether color blindness results from lack of one pigment, and

even whether the color-mix data on color blindness are right. Different

workers get different results. This field is still very much under

development.

Fig. 35–8. The spectral sensitivity curves of a normal trichromat’s

receptors.

35–6 Physiochemistry of color vision

Now, what about checking these curves against actual pigments in the

eye? The pigments that can be obtained from a retina consist mainly of

a pigment called visual purple. The most remarkable

features of

this are, first, that it is in the eye of almost every vertebrate

animal, and second, that its response curve fits beautifully with the

sensitivity of the eye, as seen in Fig. 35–9, in which

are plotted on the same scale the absorption of visual purple and the

sensitivity of the dark-adapted eye. This pigment is evidently the

pigment that we see with in the dark: visual purple is the

pigment for

the rods, and it has nothing

to do with color vision. This fact was

discovered in 1877. Even today it can be said that the color pigments

of the cones have never been obtained in a test tube. In 1958 it could

be said that the color pigments had never been seen at all. But since

that time, two of them have been detected by

Rushton by a very simple and beautiful technique.

Fig. 35–9. The sensitivity curve of the dark-adapted eye, compared with

the absorption curve of visual purple.

The trouble is, presumably, that since the eye is so weakly sensitive

to bright light compared with light of low intensity, it needs a lot

of visual purple to see with, but not much of the color

pigments for seeing colors. Rushton’s idea

is to leave the pigment in the eye, and measure it anyway. What

he does is this. There is an instrument called an ophthalmoscope for

sending light into the eye through the lens and then focusing the light

that comes back out. With it one can measure how much is reflected. So

one measures the reflection coefficient of light which has gone

twice through the pigment (reflected by a back layer in the

eyeball, and coming out through the pigment of the cone again). Nature

is not always so beautifully designed. The cones are interestingly

designed so that the light that comes into the cone bounces around and

works its way down into the little sensitive points at the apex. The

light goes right down into the sensitive point, bounces at the bottom

and comes back out again, having traversed a considerable amount of the

color-vision pigment; also, by looking at the fovea, where

there are no rods, one is not confused by visual purple. But the color

of the retina has been seen a long time ago: it is a sort of orangey

pink; then there are all the blood vessels, and the color of the

material at the back, and so on. How do we know when we are looking at

the pigment? Answer: First we take a color-blind person, who has

fewer pigments and for whom it is therefore easier to make the analysis.

Second, the various pigments, like visual purple, have an intensity

change when they are bleached by light; when we shine light on them they

change their concentration. So, while looking at the absorption spectrum

of the eye, Rushton put

another beam in the whole eye, which changes the concentration of

the pigment, and he measured the change in the spectrum, and the

difference, of course, has nothing to do with the amount of blood or the

color of the reflecting layers, and so on, but only the pigment, and in

this manner Rushton obtained

a curve for the pigment of the protanope eye, which is given in

Fig. 35–10.

Fig. 35–10. Absorption spectrum of the color pigment of a protanope

colorblind eye (squares) and a normal eye (dots).

The second curve in Fig. 35–10 is a curve obtained with a

normal eye. This was obtained by taking a normal eye and, having already

determined what one pigment was, bleaching the other one in the red

where the first one is insensitive. Red light has no effect on the

protanope eye, but does in the normal eye, and thus one can obtain the

curve for the missing pigment. The shape of one curve fits beautifully

with Yustova’s green curve,

but the red curve is a little bit displaced. So perhaps we are getting

on the right track. Or perhaps not—the latest work with deuteranopes

does not show any definite pigment missing.

Color is not a question of the physics of the light itself. Color is a

sensation, and the sensation for different colors is different

in different circumstances. For instance, if we have a pink light,

made by superimposing crossing beams of white light and red light (all

we can make with white and red is pink, obviously), we may show that

white light may appear blue. If we place an object in the beams, it

casts two shadows—one illuminated by the white light alone and the

other by the red. For most people the “white” shadow of an object

looks blue, but if we keep expanding this shadow until it covers the

entire screen, we see that it suddenly appears white, not blue! We can

get other effects of the same nature by mixing red, yellow, and white

light. Red, yellow, and white light can produce only orangey yellows,

and so on. So if we mix such lights roughly equally, we get only

orange light. Nevertheless, by casting different kinds of shadows in

the light, with various overlaps of colors, one gets quite a series of

beautiful colors which are not in the light themselves (that is only

orange), but in our sensations. We clearly see many

different colors that are quite unlike the “physical” ones in the

beam. It is very important to appreciate that a retina is already

“thinking” about the light; it is comparing what it sees in one

region with what it sees in another, although not consciously. What we

know of how it does that is the subject of the next chapter.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Committee on Colorimetry, Optical Society of

America, The Science of Color, Thomas Y. Crowell Company,

New York, 1953.

HECHT, S., S. SHLAER, and

M. H. PIRENNE, “Energy, Quanta, and Vision,”

Journal of General Physiology, 1942, 25, 819-840.

MORGAN, CLIFFORD, and

ELIOT STELLAR, Physiological Psychology, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1950.

NUBERG, N. D. and E. N. YUSTOVA, “Researches on Dichromatic Vision and the Spectral

Sensitivity of the Receptors of Trichromats,” presented at Symposium

No. 8, Visual Problems of Colour, Vol. II, National

Physical Laboratory, Teddington, England, September 1957. Published by

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1958.

RUSHTON, W. A., “The Cone Pigments

of the Human Fovea in Colour Blind and Normal,” presented at

Symposium No. 8, Visual Problems of Colour, Vol. I,

National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, England, September

1957. Published by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1958.

WOODWORTH, ROBERT S.,

Experimental Psychology, Henry Holt and Company, New York,

1938. Revised edition, 1954, by Robert S. Woodworth and H.

Schlosberg.