French visual and narrative artist Sophie Calle blurs the distinction between fact and fiction by using the material of daily life coupled with storytelling. Through the interplay between staged experiences and her narratives, she constructs herself as an artistic subject. Her creative process produces a narrative body that alters with each story she tells. Most critical reception of Calle’s work focuses on her blurring of fact and fiction, especially the use of the intimate as raw material for her art. While her artful storytelling engenders such an interpretation, I suggest that Calle tells a narrative of intimacy, rather than displaying intimacy itself. At first this distinction may seem minor; however, the level of storytelling in Calle’s work reveals complex orchestrated projects that seduce the spectator. Calle’s art demonstrates what I call orchestrated reflexivity since it depends on her presence, her idea for the project, and the story that emerges from the experience. Her construction of art under the guise of her life raises questions about the production of art, especially in terms of authenticity and authorial intervention. Calle employs the other in the act of storytelling throughout her work to shore up artistic authority; she especially uses the figure of the absent other in her work since 2007. I argue that Calle’s purposeful blurring of truth and fiction work underscores the art of storytelling, but more importantly, it produces the artist, not only as a figure with absolute authority but as the narrative itself.

If we compare Calle to any number of artists, from the Surrealists to the Situationists, from authors of the nouveau roman to those of autofiction, from Claude Cahun to Carolee Schneemann, her work manages not only to echo other avant-garde tendencies in art and literature, but to create a unique form of contemporary art through experiential storytelling and visual documentation based on an idea—a controlled, clearly delineated rule of the project.[1] Through orchestration of daily activities while adhering to established rules, Calle imposes order and control but needs chance and convoluted interactions with others for her projects to work. The coupling of text and image, trace and absence, and orchestrated experience and storytelling characterizes Calle’s unique contemporary art. The significance of Calle’s work lies in its ingenious inability to be pinned down. This ambiguity results from her intriguing storytelling through both text and image and from her manipulation of the spectator’s desire to know more about the purposeful conflation of art and life in her work. Calle’s work and her status as a contemporary artist make a case for artistic production at the interstices of oppositions as an investigative way to look, to create, to document, and to be in the world.

Calle, born in 1953, came to art without any formal artistic training. Her father, Robert Calle, a doctor, art collector, and museum director, introduced her to art at a young age. Her parents divorced when she was young and she lived with her mother, a book critic and press attaché. After receiving her baccalaureate in her late teens, Calle traveled internationally for seven years, doing odd jobs to pay her expenses. She returned to Paris in her mid-twenties and did not know what to do with herself.[2] Calle claims that she undertook various activities—following strangers in the street, for example—to fill a void, without an artistic goal in mind:

The first work I made, in 1979 [at age 26], was only shown in the form of a book. I had come back to France after seven years of traveling, and when I arrived in Paris, I felt completely lost in my own town. I no longer wanted to do things I used to do before, I no longer knew how to occupy myself each day, so I decided that I would follow people in the street. My only reason for doing this was that since I had lost the ability to know what to do myself, I would choose the energy of anybody in the street and their imagination and just do what they did. I didn’t take photographs or write texts. I just thought every morning that I would see where they went and let them decide what my day would be, since alone I could not decide.[3]

Calle’s motivation for following strangers in the street suggests that her emptiness and lack of direction were so great that she sought completion and purpose through the action of others’ energy. There is an important depersonalization of Calle at work here: she is implicated in the act of following but subsumes her action to that of the other person. She produced her own desire as an effect of the desire of the other, underscoring the importance of the other as a driving force for her art.

In an interview with Ben Lewis, she offers another version of how she got started in the art world, which indicates narrative spinning of even the beginnings of her professional career.[4] After returning to Paris from her travels, she wanted to get her art collector father’s attention, so she looked at the art on his walls and tried to do the same thing. She actually uses the word “seduce,” implying an attempt to beguile, maneuver, or lure. Calle does not give any more details to this story, but since her father supported contemporary artists including Christian Boltanski and Annette Messager, one can imagine that she saw avant-garde works and wanted to try her hand at experimental practices. In both narratives of her artistic beginnings, the desire of the other—strangers in the street or her father—motivates her expérience and sets her on the path of artistic creation.

The transformation of Calle into an artist occurred after the fiancée of the art critic Bernard LaMarche Vadel, then curator at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, participated in Calle’s Les dormeurs (1979) project, which she first conducted as an expérience during what I call her “pre-art” phase. Vadel subsequently became interested in Calle’s work and proposed to include it in the fortieth Biennale des Jeunes in 1980. Calle explains, “I agreed. That’s when it happened. He decided for me—that I was an artist.”[5] This comment points to the importance of the other in Calle’s artistic practice: she needs the other to decide for her. She did not consciously choose to be an artist, but it was the will of an art curator that transformed her. This passivity informs how Calle views herself as an artist and how she understands the artistic process, since she depends on circumstance and others’ participation to facilitate her project. Her work depends on the simultaneous presence and absence of herself in the work, which further emphasizes her role as the orchestrator.

Although Calle portrays the beginning of her artistic trajectory as haphazard, the perception of her projects and therefore her art subsequently changed when she made up her mind to be an artist. Ginger Danto explains, “By the early ’80s Calle was receiving widespread recognition of her work. ‘I had become an artist,’ she says coolly of her courtship by the Paris dealer Chantal Crousel . . . ; by the Pompidou Center for a 1981 show called ‘Autoportraits’; and various other venues. . . .”[6] Calle’s recognition of her projects as art marks an important moment in her entire body of work, since she henceforth has a direction and a purpose.

Calle’s project-driven expériences have garnered success in the art world: over the last thirty years, she has established herself as one of the most internationally acclaimed contemporary French artists. In 2007, she represented France in the Venice Biennale, and in 2010, the Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography was awarded to Calle. Since the early 1980s, Calle has worked in several media: texts, images, photographs, happenings, installations, and video. She made the cover of ARTnews in December 1992, and the first retrospectives of her work occurred in France in the early nineties, including one at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. In 2003, the retrospective M’as-tu vue at the Centre Pompidou further recognized her importance as a contemporary artist. In 2009, the Center of Fine Arts in Brussels held a retrospective of Calle’s work, including commentary on the “life” she constructs through her art. Her progression from accidental artist to a leading contemporary artist indicates her established presence in France and in international venues.

Calle’s acclaimed status in the art world establishes and reinforces her authority as an artist, which she uses as artistic capital in her projects. She relies on this authority to sell, both metaphorically and literally, the narrative of her projects. Furthermore, she constructs an aesthetic frame that passes art off as life in her narrative investigations, thereby blurring fact and fiction. This ambiguity between fact and fiction generated by the elements of daily life in the narrative projects renders them more believable and simultaneously incredible. She therefore successfully allures the spectator through the use of the everyday (for simplicity, I will use the terms “everyday” and “daily life” interchangeably). In 1947, Henri Lefebvre published his Critique de la vie quotidienne, and the Situationists in the mid-1950s took up his critique of everyday life by enacting experiments to transform the organization of social space.[7] For Calle, the everyday is the representational context of her art, which she employs to shore up her artistic authority. The spectator’s enthusiastic acceptance of Calle’s authority due to the engaging nature of her work, however, obscures the narrative mechanism that presents art as life.

Calle’s artistic projects bracket an element of daily life, sleeping for instance, and amplify the activity to the point of hyperbole: she establishes a premise or a situation, creates clearly defined rules, and adheres to them for a given amount of time. For Les dormeurs, she invited forty-five people (strangers, acquaintances, friends, and even the neighborhood baker) to sleep in her bed; twenty-eight people accepted. Each person had an eight-hour shift, and the participants succeeded one another around the clock for eight straight days.[8] During their stay of eight hours, she offered them clean sheets, asked them questions about their expectations of the project, observed them while they slept, and took photos of them at various intervals. Two sleepers came expecting an orgy or a sexual game; one commented that changing sheets after another person had slept in them was a bourgeois notion; some slept soundly; others changed sleeping positions quite often; and some slept naked. She observed the sleepers and documented each person with photographs and narrative description. Calle had to call a babysitting service to get a substitute when a person did not show up, and she also filled in for an absentee sleeper. Calle explains her role in Les dormeurs: “I put questions to those who allowed me; nothing to do with knowledge or fact gathering, but rather to establish a neutral and distant contact.”[9] She also established another rule: she photographed the sleeper every hour.

The sleepers agreed to participate for various reasons, but it was especially the sense of mystery that attracted people. One may have wondered: “Why is she inviting strangers to sleep in her bed?” Calle capitalizes on the potential mystery of the situation: her questions, photographs, and transformation of the sleeping activity into an event are simultaneously ordinary and peculiar, which suggests that the artist has a special power to transform the quotidian with just a touch of strangeness. The framing of the event or the ensemble of situations by the artist makes the spectator question what we do on a daily basis usually without reflection. This making extraordinary the very ordinary draws attention to the role of the artist and her own presence in the act of creation; she entangles herself in the everyday in order to transform it into something unexpected and unusual.

Calle’s participation in her projects implicates her fully even though she may not have a precise goal or purpose in mind. Not only did she mastermind the project of the sleepers, she also took part in this investigation of sleeping: her own sleeping was dictated by the actions of others for eight days. This is an important example of Calle’s art influencing her life, since her sleeping pattern was adapted to that of her sleeping subjects. She would nap when they would sleep or sleep when there was a void in the chain of sleepers. Even though Calle did not consider herself an artist at the time and did the project without a specific goal in mind, the mise en scène of the situation indicates an artistic project in the making. Moreover, the established premise with a set of rules to which others adhere establishes the basis for her art. The fact that the participants followed her rules indicates her authority in the making.

Calle’s second project, Suite vénitienne (1980, published in 1983), also reveals the important distance between herself and the situation that she controls through the establishment of a rule.[10] This concept of the rule establishes an organizing idea for each project, a cornerstone of her work, and contributes to her perceived artistic authority throughout her career. She describes the groundwork for the Suite vénitienne project that occurred during her tailings when she first returned to Paris:

For several months, I would follow strangers in the street. For the pleasure of following and not because I was interested in them. I would photograph them and note their path until I lost sight of them. In January 1980, I followed a man without his knowing, first in Paris and then in Venice. “Suite vénitienne” is the result of this tailing.

Depuis des mois je suivais des inconnus dans la rue. Pour le plaisir de les suivre et non parce qu’ils m’intéressaient. Je les photographiais, notais leurs déplacements puis les perdais de vue. Au mois de janvier 1980, je suivis à son insu, tout d’abord à Paris, puis ensuite à Venise, un homme. “Suite Vénitienne” est le relevé de cette filature.[11]

Calle’s subsumed will is displaced by that of the other—where Calle goes would depend on where the other person wanted to go. She chooses the person based on something that attracted her, a coat or hat, for example, which reinforces the idea of the strange in terms of both the unusual and the unfamiliar. She then lets the other person decide where to lead her, her presence practically becoming a shadow. Her activity ends when the person leads her to a place where she could not follow, for example, the individual’s home. She later started photographing these strangers and jotting down descriptions of them and of what she did in a notebook. A tension therefore exists between the rule that Calle determines for the particular activity and the will of the other who also influences the unfolding of the action.

The orchestrated event of following, coupled with chance, creates the possibility of an encounter with another for Calle; however, she ultimately chooses to keep the other at a distance. In one particular incident that led to the creation of Suite vénitienne, Calle started following a man during the day, lost track of him, and then later saw him a second time at a gallery. Struck by the coincidence, she approached him and explained that she had followed him during the day. He did not seem surprised by the information and during the course of their conversation mentioned that he was leaving for Venice the next day. With this information, she took a train to Venice the next day to continue following him. She documented this activity by taking photos of him from afar. The element of distance is important in this project, because her goal is to follow him, not to get to know him. When he finally discovers that she is following him and confronts her, the diversion loses its purpose. While in Venice, she learns when Henri B., the name Calle uses for the man, is supposed to leave Venice and arrive in Paris. She takes an earlier train to Paris, so she can be there for his arrival and take one last photograph. Suite vénitienne, as she later named the collection of photos coupled with her journal, was first exhibited in 1980 and then published in 1983.

Calle’s pursuit of Henri B. evokes trace, absence, and the other—dominant themes developed throughout her work—since she records only traces and shadows of him. She photographs where he has been, takes photos from the vantage point that he just vacated, and captures glimpses of him. Jean Baudrillard in his afterword to Calle’s Suite vénitienne explains the significance of the other and trace in the act of following:

The other’s tracks are used in such a way as to distance you from yourself. You exist only in the trace of the other, but without his being aware of it; in fact, you follow your own tracks almost without knowing it yourself. (Le réseau de l’autre est utilisé comme façon de vous absenter de vous-même. Vous n’existez que dans la trace de l’autre, mais à son insu, en fait vous suivez votre propre trace, presque à votre insu.)[12]

The notion of trace suggests a sign of absence, the vestige left by the person whom she follows. In this case, Henri B. leaves a double trace of absence since he would not give permission to Calle to have his image used. When she wanted to exhibit and publish this project, she had to return to Venice and restage it and retake the photos using another man. From the very beginning, the absent other occupies a central role in her projects.

Baudrillard’s concept of trace is especially significant here because her documentations of following record a material trace of the activity, a reminder of her self-effacement. Her vanishing is illusory, however, since everything goes through her: her perspective, her description, and her journal. Although Calle acts as the grand architect of her projects, setting everything in motion, she must experience what unfolds. Her work exemplifies par excellence the double meaning of une expérience in French as both an experiment and an experience.

This project not only reveals the artist’s perspective and subjectivity, but displays a mysterious impression of the artist: when a street vendor offers to take a photograph of her, she accepts. Documentation of Calle in a blond wig playing with pigeons in a square in Venice is her visual imprint on the project, registering her presence.

Both the experimental and experiential elements of daily life and self-representation are the underpinnings of the ambiguous relationship between fact and fiction in Calle’s work. Shirley Ann Jordan has used the term “process-driven project art” to describe Calle’s artistic endeavors since her work does not merely foreground a concept but also depends on the experiential elements of the happening.[13] In an interview Calle explains that she provokes situations but importantly attempts to live them.[14] To a certain extent her experimental projects can be compared to dares, since the premises of her projects are often provocative or skate the boundaries of social norms. The experimental is the driving force (le moteur) that allows her to live certain experiences that she did not anticipate, but she does qualify that these occurrences are ordinary and banal.[15] Since these experimental lived experiences happen in the context of daily life, I contend that it is precisely for this reason that fact and fiction collapse together in Calle’s world: the experimental and experiential therefore become interchangeable.

In Les panoplies (published in 1998 but documented in the early 1980s), Calle experiments with being a stripper: she deliberately occupies the position of receiver of the audience’s gaze as a sexual object but is also the subject of her project. In the early 1980s, Calle took a job as a stripper in the Pigalle district and asked a friend to take photos of her while she was on stage. The series of photos in Les panoplies consists of twenty photos illustrating her striptease act. The first photo shows the stage with several women waiting for their act with a master of ceremonies announcing the acts. Calle emerges from the group of women to perform. She is wearing a long black dress, a boa, a blond wig, a hat, stockings, and black high-heeled shoes. The next photos show Calle posing in various positions, including one with her leg poised on the step of the stage. She is seen wearing a black bra, underwear, and a thigh-high garter belt in photos eight and nine. She reaches to detach the stockings from the garter and then reaches back to take off her bra in the next photo. A middle-aged man stage right of her gazes up at her intently. The man is in the same position in the next photo of a topless Calle looking up defiantly. In the last two photos of the series, Calle is naked with a boa draped around her shoulders; in the last photo she faces the audience. The demonstrative quality to the work of Calle—she wants us to look at her—underscores the look and her positionality in this expérience. Since Calle deliberately takes up the position and image of the object of the male gaze, one wonders at first what her purpose of assuming the role of the stripper and discarding it easily is.

This expérience, conducted before she became an artist and published after she had become one, highlights indeed the power of observation in Calle’s experiential experiment. She states that she was not an artist when she performed as a stripper and that she did it for the money. She also did it to overcome her past feminist opposition to stripping.[16] The fact that she had the act documented makes one wonder how she considered her act and the position she was occupying on stage at the time. Calle explains that while traveling in California someone had asked her to do exotic dancing or stripping at a club. Due to her feminist position at the time, she refused, but admitted it was something that she wanted to do as a challenge to herself. When she returned to Paris and was offered a job at a strip club in Pigalle, she accepted.

Calle’s motivation to perform the striptease acts––it was something that she wanted to do, but felt it previously went against her convictions—points to her desire to experience this kind of embodiment. Her act begs further scrutiny, since she did not merely perform once and leave, but continued for a short period of time.[17] By asking a friend of hers to photograph her striptease, Calle simultaneously occupies two positions at once: the performer on stage and the artist hors scène. Even though she is not directly behind the camera, she is directing her friend’s actions; that is, her role as artist implies a double position for her.

Calle’s multiple positions in Les panoplies and her mise en scène as a stripper draw attention to her body and the ways of looking at the female body. Her body implies the “to-be-looked-at-ness” that Mulvey argues in terms of male spectatorship and the female body. By literally exposing her body to the audience at the club and then to a larger audience by publishing the photos, she highlights the specificity of her female body and evokes the associations and connotations of representation of the female body. Does she alter codifications of the female body in this embodied performance? Since she, as a female artist, creates this situation and mise en scène, she alters the passive component to Mulvey’s theory. By actively putting herself into a scenario that has traditionally relegated women to positions of objects of a male desire, she questions this paradigm through herself as the actor in this situation.

In La filature (1981), the piece that was commissioned for her first Centre Pompidou exhibit, Calle is also simultaneously the artist, the subject of the work, the photographic object, and the narrative force of the story, all wrapped up in an experiential story.[18] Calle asked her mother to hire a detective to follow her for a day to prove that she existed. This reason harks back to the following of strangers in the street––to mask her emptiness or to be filled by the other’s desire; she not only wants photographic proof of her existence but also wants a motivation for various daily activities. Knowledge of the other’s look motivates her to undertake certain activities; the awareness of his presence is the impetus for her itinerary of actions that day. The piece consists of the detective’s report of the day following Calle, including photos of her, contrasted with her narrative and telling of the events of the day.

Calle constructs her narrative of the day in a way that resembles the detective report: she gives the time of her activities and uses concise sentences describing her activity. An important element, however, separates the two versions of the day: Calle’s subjectivity as the artist and catalyst of this project comes through very clearly:

Thursday, April 16, 1981, 10 a.m. I am getting ready to go out. Outside, in the street, a man is waiting for me. He is a private detective. He is paid to follow me. I hired him to follow me, but he does not know that. At 10:20 a.m. I go out. In the mailbox, a postcard from Mont Saint-Michel. . . . The weather is clear, sunny. It’s cold. I am wearing gray suede breeches, black tights, black shoes, and a gray raincoat. Over my shoulder a bright yellow bag, a camera.

Jeudi 16 avril 1981. 10 heures. Je m’apprête à sortir. Un homme m’attend dans la rue. Il est détective privé. Il est payé pour me suivre. Je l’ai fait payer pour qu’il me suive et il l’ignore” A 10h20, je sors. Je trouve au courrier une carte postale du Mont-Saint-Michel. . . . Le temps est clair, ensoleillé. Il fait froid. Je porte des knickers de daim gris, des bas noirs, des chaussures noires et un imperméable gris. En bandoulière un sac jaune vif, un appareil photographique.[19]

Since he does not know that Calle was the person who hired him, his participation is key to the deception of the project. His ignorance makes the project similar to Calle’s following others since the strangers in the street or Henri B. did not know that they were being followed. In addition, the contrast between Calle’s narrative of the day and that of the detective is striking; his style relays the facts of his observations and does not convey a personal subjectivity. He documents the beginning of the day:

REPORT

Thursday, April 16, 1981

At 10:00 a.m. I take up position outside the home of the subject, 22 rue Liancourt, Paris 14th.

At 10:20 the subject leaves home. She is dressed in a gray raincoat, gray trousers, and wears black shoes with stockings of the same color. She carries a yellow shoulder bag.

Jeudi 16 avril 1981 Rapport A 10 heures, nous prenons la surveillance devant le domicile de la surveillée, 22, rue Liancourt à Paris 14e. A 10h20, la surveillée quitte le domicile. Elle est vêtue d’un imperméable gris, d’un pantalon gris et porte des chaussures noires ainsi que des bas de même couleur. En bandoulière un sac de couleur jaune.[20]

Calle’s introduction focuses on the presence of the detective, while the detective reports Calle’s actions but does not understand the significance of them. He mentions that she enters and exits the hair salon and crosses the Jardin du Luxembourg, but he does not have any idea about the motivations behind Calle’s activities.

In addition to the differences in style, a divergence in the narratives toward the end of the day sets the two versions apart: Calle’s version of the day does not match with that of the detective. At the point when she enters the movie theater, her account differs from the detective’s report. At some point she leaves the movie theater and then specifies leaving a gallery at 8:00 p.m. to attend a party with friends. She goes to a café to eat at 2:00 a.m. and then leaves for a friend’s hotel three hours later. She wonders if the detective liked her and if he will think of her the following day.[21] The detective has her watching the movie on the Champs-Elysées until 7:25 p.m., later leaving the cinema, where she takes the metro at the Franklin D. Roosevelt station, changing at Trocadéro, and getting off at the Denfert-Rochereau station. He stops following her at 8:00 p.m. when she returns home.

The narrative discrepancy between the two accounts points to a possible rift in Calle’s authorial authority. The spectator is left wondering if the detective stopped following her at 5:30 p.m. and made up the rest of his report. Calle’s friend who briefly followed the detective confirmed that the detective entered the cinema at 5:30 p.m., five minutes after Calle. Did he mistake someone else who resembled her and follow that person who happened to live in Calle’s neighborhood? Perhaps he took a break, assuming that Calle would watch the entire film, and when he could not find her, he made up the rest of his report. Are we more inclined to believe Calle or the detective? Perhaps it was Calle who changed the ending to her day to present a different image of herself. Since documentation does not exist for either version, only the respective narratives, the spectator might feel tempted to believe Calle because of her authorial authority. Her self-presentation depends on this authority, since it leads the spectator to have confidence in what she represents, but Calle’s manipulation of situations and active presence also raise doubt about the authenticity of the situations she creates. I am using the terms authenticity and authentic to mean that which is accurate and reliable, as well as the existentialist use of the word to denote an emotionally appropriate, significant, and responsible way to be in the world. Calle may, for instance, have included her friend’s photographs of the detective and his account as “proof” to corroborate her story, but there is no way to verify the detective’s account nor her own. It is this very inability to ascertain the intentions of Calle’s work and the distinction between fact and fiction that draws the spectator in, forcing her to participate in the project put into motion. The inability to distinguish fact and fiction in her work, however, makes Calle both the unreliable narrator and the unreliable artist to boot.

Calle experiments with authorized and unauthorized observation through tailing in Vingt ans après (2001), which uses the same premise as La filature and reenacts the tailing of Calle twenty years later to the date by the same detective agency. Calle explains in her text that this time it was not her idea for the project, but that of Emmanuel Perrotin, owner of a Parisian art gallery, who wanted to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of La filature. He ostensibly notified her of the project when he learned that she would not be in Paris for the long Easter holiday. She agreed to participate, changed her plans, and knew that April 16, 2001, would be the day. In both versions, her narrative of the day depends on the knowledge that she has been followed.

Calle’s tone toward the detective is decidedly different from twenty years before—she thinks of him but grows rather indifferent over the course of the day. She is acutely aware of the passage of time and is troubled that she does not have anything specific to show for the last twenty years:

Why this anxiety? Because I don’t know what to show my detective? Because I am unable to find something that would neatly sum up the twenty years that have gone by? If I’d had children it would have been easy. Like any other parent, I would resort to the good old cliché: “This is the best thing I ever did!” And that would have been the end of it. Neat, clear-cut. I’m tired. It’s been so long since I last put myself through this kind of exercise in representation.

Pourquoi cette angoisse? Parce que je ne sais que montrer à mon détective? Parce que je ne trouve rien qui résume efficacement les vingt années qui se sont écoulées? Si j’avais eu des enfants ce serait simple, j’aurais recours, comme tous les parents, à ce cliché: “Voici ce que j’ai fait de mieux!” Et hop, problème résolu. C’est propre, tranchant. Je suis lasse. Il y a longtemps que je ne m’étais pas soumise à un tel exercice de représentation.[22]

Ironically, Calle’s artistic career has been made on exactly these very exercises in representation, but she finds it a chore in this case. Her comment indicates the close relationship between her reflexivity and signifying practices: the form, the exercise in representation, draws attention to artistic practice in general. In this project, she makes decisions or does activities to give meaning to this day that she knows is being documented. She agrees, for example, to work closely with Emmanuel Perrotin and his gallery, which she resisted before because she enjoyed her professional independence. The rash decision or sudden change of heart is related to the detective’s presence. She explains: “In fact, because of this detective, whom I have barely glimpsed, I have gone and committed myself to a gallery, just to make the day more special.” (En fait, voilà qu’à cause d’un détective à peine entrevu, je viens de m’unir à une galerie pour apporter à cette journée un quelque chose de plus . . . ).[23] Calle makes a decision that will influence her professional and artistic career, thus highlighting the continued ambiguity between art and life that still defines her work twenty years later.

In contrast with this tailing and the original, Calle is now an established artist, a determining factor of the project. The fact that Perrotin wants to repeat the initial project only makes sense since as an established artist, people would be interested in a reiteration of her original project. In this rendition, Calle takes the detective to “[her] temporary exhibit at the Centre Pompidou” (cette fois, [elle va] lui montrer la salle qui [l]’est consacrée actuellement au Centre Pompidou).[24] It is significant that she wants to show the detective her exhibit at Beaubourg, since it is a way for her to affirm her status as an artist that she has gained over the last twenty years. Her anxiety about her professional accomplishments contrasts with her aloof attitude about her projects during her pre-art phase when she followed people at random.

In a way that parallels the original project, a discrepancy arises between her narrative and the documentation of the detective, further muddying the waters of fact and fiction. This time we want to believe the detective, since Calle goes too far in her narrative high jinks. She claims to have arrived at her car and left her parking spot at 5:45 p.m. to show the detective the apartment building from where Bénédicte Vincens—barefoot—fled during a fire the night of February 26, 2000, and has not been seen since. In her diary, Bénédicte wrote that she wanted to live her life like Sophie Calle, which a detective mentioned to the press. Calle’s name was included in Le monde and Les inrockuptibles in reference to this missing young woman, and an inspector contacted Calle. Since she had become implicated in this story, Calle visited Bénédicte’s burnt-out studio, spoke with her friends, removed ashes, burnt negatives and photos that Bénédicte had taken, and took photos of the studio. Once again, the spectator questions the authenticity of the project, as well as Calle’s authorial authority, while experiencing malaise in the observation of this story.

Calle inserts this narrative backstory in her text, which serves as motivation for her narrative lapse or the discrepancy between her account and that of the detective. She explains:

I do want my detective to share this theme that we have in common, and I lead him to the girl’s building. Next door there is a real estate office. A woman is reading the missing person notice in the window. She murmurs a name: Bénédicte. Does she know her, I ask. Yes, I am her mother. I introduce myself. She puts her arms around me, tells me how much her daughter admired me.

Je souhaite partager avec mon détective un thème qui nous rapproche et je le conduis devant le domicile de la disparue. A côté, il y a une agence immobilière. Une dame regarde l’avis de recherché toujours affiché en vitrine. Elle murmure un prénom: Bénédicte. Je me retourne. Je lui demande si elle la connaît. Oui, dit-elle, je suis sa mère. Je me présente. La femme m’enlace. Elle dit que sa fille m’admirait.[25]

This ostensibly haphazard meeting with Bénédicte’s mother creates the opportunity for the missing young woman who admired Sophie Calle to become the subject of Calle’s project, Une jeune femme disparaît. Calle expresses the worry that the detective may have lost contact with her and did not witness this important moment that gave meaning to her day:

I have nothing more to offer my detective. If he has lost track of me, he will have missed the one moment of grace in a tedious day. And yet it is to him that I am indebted for this meeting. (Je ne peux rien offrir de plus à mon détective. S’il a perdu ma trace, il aura raté l’instant délicat d’une journée laborieuse. Pourtant, c’est à lui que je dois cette rencontre.)[26]

Calle’s knowledge of the other, the detective in this case, shapes her itinerary for the day: her desire to show him traces of Bénédicte, the missing other, further underscores the absent other at the heart of her project.

The ambiguity between fact and fiction in this project makes any attempt to establish authenticity pointless, thus bolstering Calle’s absolute narrative authority in this closed circuit of her invention. Calle’s narrative intertextualities establish Bénédicte’s story as the basis for Une jeune femme disparaît, which features the story of her disappearance, her burnt negatives, photos of her studio, and an empty chair with an explanation that Bénédicte happened to work as a museum guard in the very galleries of the Centre Pompidou where Calle’s exhibit is housed. The story is too good to be true! And that is the very point. Since the Bénédicte story is so far-fetched and creepy, one wonders if Bénédicte was somehow complicit or collaborated with Calle on this project. The detective’s report in Vingt ans après states that after losing her at the exhibit they waited for Calle at her car until she arrived at 6:20 p.m., the time that Calle has herself leaving Bénédicte’s mother, opening a window of doubt that the inclusion of the Bénédicte story is indeed a narrative parenthesis. Calle asserts her narrative authority at the end by stating, “I don’t even wonder if he’s there, or if he gave up following me hours ago. I don’t really care” (Je me demande pas même pas s’il est là, dehors, ou s’il m’a depuis longtemps, abandonnée. Au fond, ça m’indiffère).[27] Indeed, the detective’s presence is motivation of her authorial intervention, and the discrepancy between his narrative and hers shores up Calle’s authority since the spectator wants to believe her version.

The distinction between narrative, tales, and ostensibly real events is not always easy to make in Calle’s work. In an interview, Bice Curiger asks about her relationship to the false and the real. She replies:

Everything is real, everything is true in the works, there is just generally one lie included, but the lie is related to a frustration. For example, in the hotel rooms everything is true. . . . There was a room I would have liked to find, and this room never appeared. So, . . . I took an empty room and filled it with what I would have wished to find.[28]

Calle is referring to her L’hôtel (1984) project, for which she took a job as a maid in a hotel in Venice. Cleaning the rooms gave her access to the guestrooms that she then photographed. The published text consisted of both photographs and descriptions of the objects in the room, a catalog of the occupants’ possessions. The claim that all is true in her work except for a particular aspect that she fabricates raises questions about the construction of the entire project. If the spectator cannot distinguish which element is found or fabricated, then her claim to truth points to the ambiguity of this discernment. By pointing out the invented element of the project, Calle in turn casts doubt on the truth or authenticity claims of her art. Calle, however, “says that her photographic tableaux and texts report the activity between truth and fiction.”[29] I propose that if truth and fiction bracket her work or delineate the set of her projects, then indeed Calle explores fertile ground between those two extremes. To be exact, she enjoys shuttling the spectator back and forth between the two poles to create a disorienting effect. Johnnie Gratton uses the term “truth value” to describe Calle’s narratives qualitatively. He quotes Paul Auster’s character, Maria, to specify the nature of her work: “‘[Sachs] understood that all of my pieces were stories, and even if they were true stories, they were also invented. Or even if they were invented, they were also true.’”[30] The “truth value” lies then not in the fact or actual occurrence of the story or event, but rather in the spectator’s or reader’s perception whether the description somehow rings true with the spectator or reader. Likewise, for a true story to be also invented indicates the narrative frame of any event the moment the enunciator relays the story to an interlocutor.

The entire premise of Doubles-jeux (Double Game), a collaborative project with American novelist Paul Auster, is to explore narrative processes, specifically when one story incorporates facts only to modify them into new fictional elements. In his book Leviathan (1992) some aspects of his character Maria are taken from Calle and others are invented. According to Calle, Auster borrowed from a number of her works including “The Wardrobe, The Striptease, To Follow. . . , Suite vénitienne, The Detective, The Hotel, The Address Book, and The Birthday Ceremony” (la suite vénitienne, la garde-robe, le strip-tease, la filature, l’hôtel, le carnet d’adresses, le rituel anniversaire).[31] On the original of the French copyright page, Calle circles her clue with red ink to ensure that the reader sees it: “The author extends special thanks to Paul Auster for permission to mingle fiction with fact” (L’auteur remercie tout spécialement Paul Auster de l’avoir autorisée à mêler la fiction à la réalité), and Auster likewise thanks Calle using the same formula on his copyright page.[32] In Double Game, Calle takes on the life of Maria, changes the fictional elements in Maria’s story back to her own, and then uses some of the fictional elements as bases for her own installations. Calle establishes the rules of the project from the onset:

The Rules of the Game / In his 1992 novel Leviathan, Paul Auster thanks me for having authorized him to mingle fact with fiction. And indeed, on pages 60 to 67 of his book, he uses a number of episodes from my life to create a fictive character named Maria, who then leaves me to live out her own story. Intrigued by this double, I decided to turn Paul Auster’s novel into a game and to make my own particular mixture of reality and fiction.

La règle du jeu / Dans le livre Léviathan, . . . l’auteur, Paul Auster, me remercie de l’avoir autorisé à mêler la réalité à la fiction. Il s’est en effet servi de certains épisodes de ma vie pour créer, entre les pages 84 et 93 de son récit, un personnage de fiction prénommé Maria, qui ensuite me quitte pour vivre sa propre histoire. / Séduite par ce double, j’ai décidé de jouer avec le roman de Paul Auster et de mêler, à mon tour et à ma façon, réalité et fiction.[33]

Auster, for example, wrote about another ordering game:

At other times, she would make similar divisions based on the letters of the alphabet. Whole days would be spent under the spell of b, c, or w, and then, just as suddenly as she had started it, she would abandon the game and go on to something else. (D’autres fois, elle observait des divisions analogues fondées sur les lettres de l’alphabet. Des journées entières s’écoulaient sous le signe du b, du c ou du w et puis, aussi brusquement qu’elle avait commencé, elle abandonnait le jeu et passait à autre chose.)[34]

Calle, in turn, chose certain days to live under the sign of the letters specified by Auster.

Challenging the distinction between fact and fiction in this way has significant theoretical consequences for Calle’s work, since it emphasizes the process of narration and storytelling in her projects. By deliberately assuming the actions of a fictive character, she makes her life and art a mise en abyme of narrative creation and brings to life the act of storytelling. Auster’s words become flesh in Calle’s actions and, in turn, return to representation as she is photographed in a blond wig in the Montparnasse cemetery. The repetition of the blond wig in Calle’s work highlights disguise, deception, and temporarily becoming another in addition to showing the false. In De l’obéissance, Livre I, Doubles-jeux, she includes the excerpts of Auster’s texts that were based on her, crosses out the fictional parts in red, and highlights the scenarios represented by her in her series (Livre I, II, III, etc.). This intertextual collaboration demonstrates a deliberate manipulation of the text to show different layers of representations and purported facts of Calle’s life and career that she embeds in the project.

Calle’s establishment of specific criteria—related to control—is a form of ordering, since she mediates the experience. In “Le régime chromatique,” food takes on a color according to the day of the week, as she orders and arranges the daily task of eating in an innovative way. The ordering of the everyday is based on a game between Auster and herself. The artistic project is the mode by which she lives for a given time, or so the story goes. In “Le régime chromatique,” Calle creates and photographs meals for each day of the week:

To be like Maria, during the week of December 8 to 14, 1997, I ate Orange on Monday, Red on Tuesday, White on Wednesday, and Green on Thursday. . . . (Pour faire “comme Maria”, durant la semaine du 8 au 14 décembre 1997, j’ai mangé orange le lundi, rouge le mardi, blanc le mercredi et vert le jeudi. . . .)[35]

On Monday, her menu included puréed carrots, boiled prawns, cantaloupe, and orange juice. The daily gesture of eating—an activity most people do without thinking––becomes a game, a carefully planned moment, eating with flair.

Calle wanted to continue their intertextual game and asked Auster to make up a fictional character to whose actions she would try to adhere. She told him that he had complete license to invent what he wished up to a period of a year. He declined, saying that he would not bear that degree of responsibility for someone’s life. Instead, Auster provided instructions on how to live in Manhattan for a week and Calle followed his instructions, photographed installations she created on the street, and recorded a diary of her experiences. In this project, Gotham Handbook (1994, published 1998 in Doubles-Jeux), she decorates a phone booth in New York City, maintains snacks inside it, and smiles at passersby for a week. Once again, Calle lives the fiction created by Auster, which raises questions about the nature of the action once it is enacted. Is it still fiction? The transformation of the fictive into lived experience can be read as a continuation of the narrative or as an experiential interpretation of a story. In either case, it is the narrative turned into lived experience that is of utmost importance, since the experiential element adds another element to the project conceived as art. Auster takes events in Calle’s life and transforms them into fiction, and Calle in turn takes up the fiction in his text and lives it. This back and forth between her life and the fictional character raises the question about whether there is indeed a true “fact” which is the starting point—the project within a project is already the moment of departure.

The visual element in Calle’s work is fundamentally significant, since she photographs her happening or the object of study and then explains her perception of it in narrative form. She does not rely on one technique to the exclusion of the other but uses both to create a unique point of view and way of seeing her daily life and others’ place within it. In 1992, Calle departed briefly from still photography and experimented with video to create another version of herself as artist in No Sex Last Night.[36] Although the form differs from her previous work since she shares artistic control with Greg Shephard, this project makes even more visible her modus operandi: she profoundly needs the narrative other in order to exist as an artist.

Calle’s video in collaboration with Greg Shephard, No Sex Last Night, is an important example of art producing life as well as a mise en scène of the quotidian. In the tape, Calle uses video as a means of capturing her body, the everyday, and her life on a road trip as the object of the video project. Calle and Shephard, using two video cameras, recorded their trip from New York to the West Coast. They videotape each other, the landscape, daily occurrences, and their conversations. Each morning Calle reports, with a corresponding shot of an empty bed, “no sex last night.” The form of the journal intime for Calle and Shephard creates ample opportunity for narrative commentary to emerge throughout the video, since it is ideal for both the revelation of intimate thoughts and daily encounters. The spectator is often left wondering whom to believe, since their perspectives often contradict one another.

In the video, Greg comments that he was first attracted to Sophie because she constantly reinvents herself. He explains: “Being with Sophie means being willing to become subject matter because there is no separation between her work and her life. Her art is how she invents her life” (my emphasis).[37] He too maintains the narrative of her art as life: through her art, her life takes form. This is similar to Cabrera’s assertion, but qualitatively different since Calle does not offer authenticity to her spectators but absolute authority. Her art is presented through the filter of her life, but the representational bracketing of these expériences makes them first and foremost art.

The excuse to make the video was a way for Calle to be with Greg a little bit longer. She uses the creation of art as a way for her to live with him for at least the duration of the road trip. In the opening voiceover, she explains that the two had plans to drive cross-country, but due to the deterioration of their relationship, she was afraid that he would refuse to go and she therefore proposed that they make a film. Calle weaves the narrative background of the project:

The desire for film, that’s Greg. But the idea of this film, that’s me. During that time we had been living together for a year and we had planned on taking a trip across the states. Our relationship had deteriorated to the point that I knew he would refuse to go, and I said to myself that if I proposed to make a film, which was his dream, then there was a chance that he would accept. In New York, since we were barely speaking, I got the idea of using two cameras instead of one.

L’envie de faire du cinéma, c’est Greg. Mais l’idée de ce film, c’est moi. A cette époque, nous vivions ensemble depuis un an et nous avions prévu de traverser l’Amérique. Notre relation s’était tellement dégradée que je savais qu’il refuserait, et je me suis dit que si je lui proposais de réaliser un film, ce qui était son rêve, j’avais une chance qu’il accepte. A New York, comme nous ne nous parlions vraiment plus du tout, j’ai eu l’idée d’utiliser deux caméras au lieu d’une.[38]

The choice to use two cameras arose from a practical consideration, but its aesthetic consequences are important, since each camera simultaneously presents the point of view of the videographer and the image of the other being filmed. Both capture their perspective and their way of seeing, but more importantly they record how the other person is seen.

The cameras serve a dual function in this video: they are not only journals in which each confides, but also a means by which the two are able to talk to one other. The possibility for communication through the act of filming underscores the importance of mediation through the technological intervention of the camera. In other words, the mode of art, in this case video, facilitates communication since the camera serves as an initial point of contact and the overall project motivates their actions. I would like to use “Sophie” to denote the person in the tape and “Calle” as the videographer; this distinction, however, is difficult to maintain and points to the collapse between the two in this project and in her work in general. In the car, Sophie confronts Greg about making a phone call to a woman in New York and immediately picks up her camera (he highlights the fact that when she asked him to talk about it, she picked up her camera). The sequence is in shot-reverse-shot form, with both having turns to speak. After Sophie explains that she felt bad waiting in the cold parking lot while Greg ostensibly went to the bathroom, she lowers the camera from her eye and Greg asks if he may respond. His explanation of what happened corresponds to a shot of him cut off at the eyes; the point of view is consistent with the position of Sophie’s camera on her lap. An interesting juxtaposition arises: the image of the other and the corresponding revelation of feelings depend on the other’s point of view. Greg captures Sophie’s image and vice versa.

The use of the two cameras reveals a dependence on the other for existence. Sophie films what she sees, even films herself in the mirror; however, the majority of the images of her come from Greg’s camera, which serves as a counterpoint to her point of view. Likewise, the images of Greg originate from the way in which she sees and considers him. The interplay between the two cameras suggests that ways of looking at others and one’s daily life are shaped by a need to be affirmed by the other.

Once again, Calle needs the affirmation of the other to confirm her existence, her visual existence in this case. The scrutiny under which the two place each other, themselves, and their surroundings illustrates a way of looking that seeks out the location of the other and self-representation as well. In this case, self-representation is interpolated through the interaction with the other: Calle’s resultant image is a composite of images of herself that she records and Greg’s vision and impressions, demonstrating the complexity and multiple praxis of self-representation.

Fact and fiction and the interplay between the two are important in Calle’s work, but in this case the presence of the two cameras in this scene provokes a moment of authenticity since Calle cannot fully control the expérience. The shot-reverse-shot pattern allows both Sophie and Greg to express themselves: the cameras act as shields, protecting one from the other, but also facilitate conversation due to this layer of protection. This moment proves to be fleeting, and Sophie reverts to control tactics to attain what she wants. Despite the fact that Greg seems to be having a long-distance relationship with a woman in New York and shows no desire for Calle, she proposes that they get married in Las Vegas and insists until Greg gives her an answer. Apparently, she had the idea even before the trip started and Greg anxiously wonders on the road: “When is she going to bring up the whole Vegas wedding idea that she’s had since before the trip?”[39] Sophie likewise thinks about when she should bring it up, considers not pursuing the idea, and finally asks him whether or not they’re going to get married in Las Vegas. In order to force Greg to give her a response, she gives him a two-hour deadline. Then she says that the hotel they choose would depend on whether or not they marry, forcing the other to participate by establishing arbitrary criteria that must be met. The confluence of video, reality, marriage, and seduction of the other resembles a reality television series avant la lettre; the artistic and representational bracketing of this project, however, makes it more theoretically engaging since Calle uses art as a motivation for the everyday details of life, for instance, driving, sleeping, and eating.

Both participate in a narrative of seduction, refusal of desire, manipulation (her imposing her will on him), and dependency: a back and forth dance. Lack of desire, sleeping, eating, and getting the car fixed fit into a larger narrative that both Calle and Shephard create simultaneously, but separately. There is, however, an uncomfortable element of prostitution or financial bargaining in No Sex Last Night—she supports Greg financially on this trip and knows that he needs the money and cannot afford to leave. She also paid a professional writer one hundred francs for her first love letter.[40] Calle buys what should be given freely—in these cases, company and expression of love. The video—a narrative of refused desire of a woman, age thirty-nine at the time, who has never been married and who is not able to attain any sex or desire—is another seduction project based on absence. The mantra “no sex last night” punctuates her frustration and makes her marriage proposal to Greg even more poignant, albeit incredible: she needs the narrative other.

The fascinating layers of narration and observation in this video expose the process of creating fiction. Both Calle and Shephard weave stories for the other––anecdotes, lies, and tales. The moments when they talk into the camera are ostensible moments of authenticity that break through the narrative fabrication. However, even these moments raise doubt or at least further questions: was this indeed filmed at the time of the shooting or afterwards? The spectator gets glimpses of what each is feeling and thinking, but their personal thoughts do not evoke confidence.[41] Their video journal seems to be another narrative form as each justifies behavior and lies to the other. Greg, for example, talks to his camera for at least a few minutes when Sophie asks him about what he is thinking. He tersely replies: “Nothing.”[42] Both a technical and narrative question is raised during analysis of this video. When were the voiceovers recorded? During the wedding scene in Las Vegas, for example, the internal thoughts of Sophie and Greg are heard in voiceover in-between the saying of the vows; that is, they could not have been recorded simultaneously with the actual filmed sequence. If they recorded the voiceover later, some thoughts could have been added during the editing of the film, which raises questions about the authenticity of their seemingly in-the-moment reflections. If passages were added during the editing process, by nature of the time delay the thoughts then would become “narrativized,” since Calle and Shephard would have had time to think about their feelings and reactions. Their comments would tell a story, rather than be a spontaneous recording of thoughts and emotions. If the two recorded their reflections shortly after the wedding, in a hotel room, for example, their comments would be still somewhat spontaneous; however, the fact that they could not have been recorded at the wedding, but are presented as simultaneous in the final edited version of the film, is a narrative sleight of hand that may go unnoticed by the spectator.

The narrative drive of the video depends on the marriage scene, since the story needs a denouement. During the editing of the film, the two learn the private thoughts of the other spoken to the camera. In Las Vegas, she wonders what made Greg change his mind about marrying her; later she learns that he did it to add dramatic interest to the film. Greg’s voiceover in the film explains that he woke up and told Sophie that he wanted to get married: he told her first thing in the morning so that he would not change his mind. Her motivations to get married are never clearly expressed either; she does mention that now she can tell her mother she will not be an old maid, which indicates the importance of her mother for the artist, especially as a figure in her work. Perhaps her reasons were similar to Greg’s desire to make the video more interesting. In any case, the video both produces and reflects their life; the artistic decision produced a life event: the two were legally married in a wedding drive-thru in Las Vegas. This is one of the most striking examples in Calle’s work of art producing life. Greg even muses that if he had known that the person issuing the marriage license would not check his identification, he would have used a false name. Legal marriage is only one effect of the video since the story continues after the video. After its completion Calle engages in a couple of artistic projects based on her marriage, including agreeing to a divorce published in Des histoires vraies (1994, 2002).[43] The divorce can be read both as another episode in the story and as a legal action that dissolves the union since the two-month trial period that Calle proposes clearly did not work out.

The repetition of the same stories throughout Calle’s work suggests a strong need to tell the same stories over and over in new contexts, always through the other. In No Sex Last Night, for instance, the voiceovers of stories that Calle tells throughout the road trip appear spontaneous, but in fact she repeats several stories that have been previously published in Des histoires vraies, without drawing attention to this fact. In Des histoires vraies, she tells short stories based on past life experiences and includes corresponding photos to illustrate them.[44] The second edition of this text, Des histoires vraies + 10, includes ten additional stories and some formatting changes. These new stories take up the narrative and journalistic thread left off in the video No Sex Last Night. She tells of a fight that she and Greg had in the spring of 1992: she used their wedding photo in front of the drive-thru chapel to cover up the hole in the wall left by a thrown telephone. She also documented a fake wedding between them in France that summer: she had a photo taken of herself in a white wedding dress with Greg, friends, and family in front of the neighborhood church in Malakoff, a Parisian suburb. She said that their fake civil ceremony was conducted by a real civil servant. This blending of the fake and the real highlights similar processes involved in the coexistence of fact and fiction in Calle’s work: she needs the ambiguity to create an element of truth. The most telling line of her text is the following one: “I crowned the truest story of my life with a fake marriage” (Je couronnais d’un faux mariage l’histoire la plus vraie de ma vie).[45] Her claim that a fabricated event is the most true or authentic moment for her indicates the power of narrative to reveal truth. Moreover, Calle’s assertion points to a convoluted effect of her storytelling: she needs others and the act of storytelling to attain a level of authenticity.

The Centre Pompidou’s exhibit of Sophie Calle’s work, M’as-tu vue, which ran from November 2003 through March 2004, not only indicates an increased interest in her work but also affirms her status as an important contemporary artist. This retrospective exhibit, a combination of old work and new projects displayed for the first time, illustrated Calle’s continuation of narrative fabrication through visual and textual means. The two most striking pieces of the exhibit were Douleur exquise (1984–2003) and Une jeune femme disparaît, the story of Bénédicte Vincens, featured in the last room. The former project occupies the first three rooms of the exhibit: the first room is entitled “Avant la douleur” and the third room is called “Après la douleur.” The middle room is a reconstructed hotel room where Calle received the phone call that ended her relationship: the spectator walks through a hotel door labeled 261 into a room with two beds with clothes strewn on one of them, carpet, a lamp, and the infamous red telephone. The third room of Douleur exquise featured the alternation of her story of the painful breakup of that relationship with other people’s stories of suffering. The repetition and distillation of her story produce variations that become more and more interesting in their reduction. Her narrative, the construction of art in the guise of life, alternates with the stories of lived experience of others. The construction of this entire exhibit, the form and physical presentation of her work, reflects the artist’s constant manipulation of images and narratives: it also mirrors the continual narrative transformation of herself as an artist through the repetition of different stories.

An unreferenced intertextuality is embedded in the very first part of the exhibit: the first section of the Douleur exquise project had been previously packaged as Anatoli (1984).[46] Calle takes an incident, a breakup with a boyfriend, in the 1980s and transforms it into a project in 2003. She gives the background to the end of her relationship:

In 1984 I was awarded a French foreign ministry grant to go to Japan for three months. I left on October 25, not knowing that this date marked the beginning of a 92-day countdown to the end of a love affair—nothing unusual, but for me then the unhappiest moment of my whole life. I blamed the trip.

En 1984, le ministère des Affaires étrangères m’a accordé une bourse d’études de trois mois au Japon. Je suis partie le 25 octobre sans savoir que cette date marquait le début d’un compte à rebours de quatre-vingt-douze jours qui allait aboutir à une rupture, banale, mais que j’ai vécue alors comme le moment le plus douloureux de ma vie. J’en ai tenu ce voyage pour responsable.[47]

Calle’s comments reveal the juxtaposition between her travel departure and the ensuing emotional upheaval: combining photos, love letters, and passports with text, she creates the story of the ninety-two days leading up to their breakup. The first room of Douleur exquise consists of ninety-two individually framed documents that bear a stamp, for example “J-2,” indicating the number of the day (“J” stands in for “jour”) prior to the painful breakup. Just as an office assistant stamps a date received on a document, Calle processes each image: the mediation of the stamp fixes it in order for her to make sense of it, leaving a trace for others. The act and the visible sign are ways for Calle both to mark and emotionally process the information, so she can move on and not dwell on it. The phrase “X days to unhappiness” suggests a reading of the days leading up to the separation in terms of the event to come. Meaning is assigned retroactively in the anticipation of day zero.

The third room of Douleur exquise, labeled “Après la douleur,” featured twenty-eight large rectangular tapestries of variations of Calle’s story alternated with twenty-eight white tapestries of stories of the most painful moment in the lives of others, including strangers. She explains:

Back in France on January 28, 1985, I opted for exorcism and spoke about my suffering instead of my travels. In exchange, I started asking both friends and chance encounters: “When did you suffer most?” This exchange would stop when I had told my story to death, or when I had relativized my pain in relation to other people’s. The method was radically effective: three months later, I was cured. The exorcism had worked. Fearing a relapse, I dropped the project. By the time I returned to it, fifteen years had gone by.

De retour en France, le 28 janvier 1985, j’ai choisi, par conjuration, de raconter ma souffrance plutôt que mon périple. En contrepartie, j’ai demandé à mes interlocuteurs, amis ou rencontres de fortune: “Quand avez-vous le plus souffert?” Cet échange cesserait quand j’aurais épuisé ma propre histoire à force de la raconter, ou bien relativisé ma peine face à celle des autres. La méthode a été radicale. En trois mois j’étais guérie. L’exorcisme réussi, dans la crainte d’une rechute, j’ai délaissé mon projet. Pour l’exhumer quinze ans plus tard.[48]

Calle chooses to dissipate her emotional pain by telling the same story over and over again until both the story and the pain have been exhausted. Strangely, it is Calle’s distilled story of the breakup told over and over again with interesting variation, repetitions, and transformations that becomes more compelling than the most painful moment in other people’s lives. Even though some of the stories treat topics more grave than a breakup, the death of a loved one, for example, they lack the narrative charge of the ensemble of the variations of Calle’s story.[49] Each embroidered tapestry of her story gradually changes in color from black to gray, reflecting the permutations of the content, while the other people’s text remains constant, black on white.

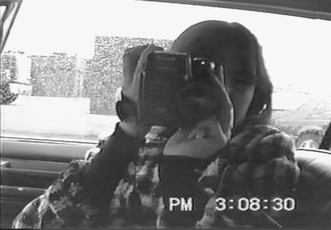

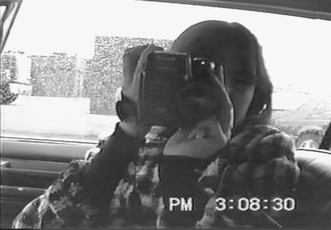

Calle’s second video project, Unfinished, shown at the exhibit reveals a highly reflexive mode of artistic creation: her inability to find an idea became the idea of the video. The enactment of the creative process, her ideas and dead ends, becomes the substance of the project in a way similar to Akerman’s self-portrait. In Akerman’s case, she had the idea for the project but did not have confidence that it is the best one possible until she had vetted all other possibilities. In Calle’s case, she has the raw material for the project but not the organizing idea, which she deems a failure. Calle explains the background of the project:

In 1988 an American bank invited me to do a project. Their automatic tellers had video cameras that filmed clients as they went unsuspectingly about their business. I managed to get hold of some recordings.

The images were beautiful but I thought if I just used them as found documents, without adding anything of my own, I would be betraying my own style. I needed an idea to go with these faces.

Fifteen years later I decided to go back over my research, delineate the anatomy of this failure and, at last, free myself of these images. Give up before their presence.

En 1988, une banque américaine m’a invitée à réaliser un projet in situ.

Les distributeurs automatiques de l’établissement étaient munis de caméras vidéo qui filmaient, à leur insu, les clients en train d’effectuer des opérations. J’ai réussi à me procurer certains enregistrements.

J’étais séduite par la beauté des images, mais il me semblait qu’en utilisant des documents trouvés, sans apport “vécu” de ma part, je ne collais pas à mon propre style. Il fallait trouver une idée pour accompagner ces visages.

Quinze ans plus tard, j’ai décidé de retracer l’histoire de cette recherché, dessiner l’anatomie d’un échec, me libérer, enfin, de ces images. Abdiquer devant leur présence.[50]

Calle’s observation of people at the ATMs without their consent continues the theme of watching and even spying. The significant difference between this project and her other work is that in this case she had the material, but not the idea, which would reinforce the claim by some that she is a conceptual artist.

Although Calle has often been called a conceptual artist, there is disputed opinion about the role of conceptual art in her work. Calle sidesteps the issue by calling herself a narrative artist.[51] Some critics see strong ties between conceptual art and her work but acknowledge important differences between the two. Conceptual art can be broadly defined as art that “communicates message and meaning through more permanent media, two-dimensional or three-dimensional or both, often in combination with printed text. The primary purpose is to convey an idea or a concept with whatever visual means are available.”[52] Whether or not one labels Calle as a conceptual artist determines to a certain extent how she is situated in terms of larger debates in the art world. As Kathleen Merrill argues:

The mode of Calle’s presentation and many ideas that motivate her ‘investigations’ clearly link her work to Conceptualism. She, too, begins with a plan to ascertain knowledge about a specific subject which she then documents by means of photographs and text. [. . .] As opposed to many Conceptualists who use a document format to analyze or deconstruct an assumed truth, Calle appropriates this technique to explore things that are unknown or unpredictable.[53]

Her early projects, Les dormeurs, Suite vénitienne, and La filature, demonstrate the approach of documentation through observations and photographs, but she does not make any claims to truth. In fact, she does the opposite. “Though they have the ‘look’ of narrative or conceptual art, Calle’s works are neither documentations of performances nor deliberate comments on the relations of image and text or of art object and viewer. In carefully orchestrated episodes, she casts herself in her work as a willful and manipulative artist,” comments Sheena Wagstaff.[54] Guy Scarpetta also argues against the idea of Calle as a conceptual artist since the role of the artist does not disappear in her work, but in fact depends on her intervention for its conception. By placing herself at the center of her work, she creates a very individualized situation.[55]

Although Calle’s projects are imbedded within a tightly constructed narrative, her action as mediation is a necessary element. She is acutely aware of her role in the process: “What was my role in the all this? I needed to act” (Quel était mon rôle? J’avais besoin d’action).[56] Her need to alter substantially what she sees indicates that her artistic agency was the missing glue of Unfinished. Indeed, the story of this search for her missing idea, how to act, becomes the story itself. She wonders if she cannot measure up to the expectations of the American bank that sent her these photos; perhaps the detail is merely part of the narrative. She wants to be through with these images, with these people waiting for their transactions to process. Telling the story of her failure, her inability to come up with a good idea for the project, becomes the story of the video. She punctuates key moments in trying to find an idea:

1988. How it all started . . . 1990. I come back . . . 1994. Help! . . . 1995. Research . . . 1997. Back to square one . . . 2002. I am overcome with doubt . . . 2003. Deliverance That leaves video. A fine artist’s video. . . . There was nothing to add. Years of failed attempts only to come back to the starting point. If this is the final form, it’s even worse than I thought. Total capitulation.

Well, since that’s where I am, why not accept these images as they are, without a story. Just for once. Say nothing. After years of not letting them be mute, that’s difficult. Silent photos, SILENT. No. I am going to vampirize them, to interfere with them. That’s the thing. This is the anatomy of a failure. This accepted fiasco is now part of the program.

1988. Comment tout a commencé . . . 1990. J’y retourne . . . 1994. À l’aide! . . . 1995. J’enquête . . . 1997. Je retourne à la case départ . . . 2002. Le doute m’assaille . . . 2003. Délivrance Reste la vidéo, une belle vidéo d’artiste. . . . Il n’y avait rien à ajouter. Des années de tentatives ratées, pour revenir au point de départ. Si la forme finale, c’est encore pire que ce que je craignais. Capitulation totale.

Tant que j’y suis, pourquoi ne pas accepter, pour une fois, ces images sans histoire. Me taire. Difficile, après tant d’années passées à refuser leur mutisme. Des photos silencieuses, SILENCIEUSES. Non. J’ai choisi de les vampiriser, les parasiter. Tout est là: il s’agit de l’anatomie d’un échec. Ce fiasco accepté fait partie du programme.[57]

Calle surmises that she should accept these silent images and be quiet. The notion of toleration is tied to this project, since Calle believes that she was not suffering enough to make a project on the topic. A tale of failure is the story—the emptiness at the center of the project occupies the narrative space. In light of Douleur exquise, it is not surprising that suffering would be part of the criteria for her creative production.[58] Her choice to use an English title to capture the incompleteness of this project is interesting, as if to create a linguistic distance between herself as the artist and the project that she deems a failure.

The title of the exhibit, however, M’as-tu vue, implicates Calle in the title by the gendered linguistic marker of the “e” while emphasizing the importance of vision and observation. In a similar way to Akerman’s stuck “e” on the keyboard in Le jour où . . ., Calle references her gender now as an established artist by indicating the feminine gender of the speaker at the end of the title, M’as-tu vue. The title’s literal meaning, “did you see me?” indeed evokes sight and observation, but the colloquial meaning of the phrase in French is translated in the English version of the exhibit catalog as “a show off” or someone or something that is “too flashy” and defined as an “allusion to the question with which actors draw attention to their success. Vain person.”[59] The cover of the exhibit book and the posters of the exhibit feature a medium close-up of Calle covering her left eye and half of her face with her left hand, obscuring her image. This is an obvious play with sight, observation, and vision, since she is covering her eye as if she were testing her vision in an eye exam. The title of the exhibit is in the form of the optometrist’s eye chart. Her name, coupled with the image of her body, is a metonymy for her work, emphasizing the importance of reading, interpreting, and decoding meaning.

Calle’s preoccupation with observation throughout her work is linked to her continual transformation of herself as an artist: by observing others and using their stories, she creates her own narratives and images of herself as the artist through visual and textual means. The last room of the exhibit, featuring La filature and Une jeune femme disparaît, reinforces this very importance of observation. To the right of the exit of the exhibit is a mirror with the phrase “M’avez-vous vue?” labeled above it and the title “L’Ombre de Bénédicte” (“Bénédicte’s Shadow”) next to it. Calle shifts from the “tu” form in the exhibit title to the formal “vous” form without an explanation for the change in linguistic register. The following quote featured on the wall brings together the theme of observation in La filature, Vingt ans après, Une jeune femme disparaît, and the entire exhibit:

I met some of Bénédicte Vincens’s colleagues at the Pompidou Center. They told me that she was interested in the behavior of visitors, and wanted to use her position as guard to study them.

For the exhibition M’as-tu vue I decided, in her name, to implement this plan.

Certain people among you therefore were observed during the visit to the exhibit.