BEAGLE SAT ALONE in the dark.

In front of him was a touch-sensitive computer screen. With it he could call up images or run entire films on any one of or all of ten Musashi G-4 HDTV screens set into the curved front wall of his video room.

The screens were arranged in two rows of five. They were flat screens and mounted flush to the wall. They had an aspect ratio of 2.4 to 1, wide enough to accommodate the full images of those films shot in the glory days of wide-screen formats like Todd-AO, Ultra-Panavision 70, and CinemaScope. When they displayed a picture from a less horizontal source, they automatically generated a flat black matte into the blank areas of the screens. The walls were painted to exactly match that black. The Center Screen of the top row was larger than the rest.

Having viewed thousands of hours of film and tape, Beagle had selected what he thought somehow defined the essence of America’s sense of itself at war. From the chosen images he had composed something that was between a history and mythology. A high-tech ten-screen version of an American Iliad. Now he was going to play that story for an audience of one, himself, in the belief that it would make him understand what sort of war he would have to direct to make his country happy.

Center Screen. Tearing Down the Spanish Flag. Just an image. A leitmotif. A trumpet call from a distant silence to start the epoch.

A flagpole against the sky. A pair of hands enter the frame. They take down the Spanish flag. They hoist Old Glory.

That was it in its entirety, shot in 1898 when America declared war on Spain.51It was the first commercial war movie.

Then, on Screen 1, up in the left-hand corner, appeared Leni Riefenstahl’s famous 1934 documentary, Triumph of the Will. Hundreds of thousands of uniformed members of the Master Race march, turn, salute, stand, sing, heil! Hitler rants. It is the declaration of the German people that they have turned themselves into the machine that will rule the world. They will annex, terrorize, invade, conquer, exterminate, incinerate—and this is the self-image in which they will do it. One people, One will. This is the image that they will sell to the world and the world will believe in even long after Hitler is dead and the war is lost.52

On Screen 5, upper right-hand corner, the other beginning: December 7th. Quiet, peaceful Hawaii. Formations of Japanese planes appear, buzzing through the silent skies.

The sneak attack. The Japanese catch American boats sitting at anchor in the harbor at Honolulu. Battleship Row, pride of the American fleet, turns into the stinking black smoke of ruin. The American planes are all on the ground. Lined up, neat and orderly. Perfect targets. Helpless and defenseless, they are destroyed. Torpedoes. Ships on fire. Planes explode. Flames. Sailors running. Two sailors with a machine gun fight back, firing at the sky. One falls. The other keeps firing.

Backstage, as it were, on the other side of the video screens, a room of industrial shelving, steel racks, bundled cable, a spaghetti land of wiring, an unmasked array of monitors and machines, Teddy Brody was watching too. When Beagle wanted a film that had not yet been loaded into the Fujitsu and digitalized, Teddy was the librarian who roamed through the racks to find it on film, tape, or disc, and put it on a projector, VCR, or player.

He loved the sequence that Beagle had assembled. The implications were so intellectually evocative that Teddy was able to forget his terrible frustrations—stuck here as librarian, not getting anywhere in his desire to be a director, not rising to a station where he could turn back to his parents and say, “Hey, you bastards, look at me, I’m making it, I don’t need you to love me anymore and I never, ever will.” What he loved most was that the base of the pyramid, the foundation, the three cornerstones, were each of them a very special fraud.

Tearing Down the Spanish Flag was not shot in Manila or Havana. It was shot on a rooftop in downtown Manhattan.53

It was a terrific commercial success. The producers, Blackton and Smith, followed it up with the more elaborate Battle of Santiago Bay, the triumph of the American fleet over the Spanish in Cuba. That one was shot in a bathtub. The battleships were cutouts and the smoke of the naval guns came from a cigarette puffed across the camera lens by Mrs. Blackton.

The gargantuan rally that Triumph of the Will showed to the world really took place. However, the rally was staged for the camera.54This may not sound particularly striking today, when all life—personal life, sporting life, political life—is rerouted around prime time. But in the thirties reality was still presumed to be real and photographs didn’t lie and no one had ever staged an event involving hundreds of thousands of people just so the camera could record them.

December 7th won an Oscar as best short documentary.55The images that it established became the reference for future films. Footage was lifted and showed up in other documentaries. When feature films were made that included the attack on Pearl Harbor, filmmakers took great care to model their work on the record created by December 7th.

But all the battle footage in December 7th was fake. The stricken ships were miniatures. They caught fire and billowed smoke in a tank, a larger, more sophisticated version of the bathtub in The Battle of Santiago Bay. The sailors running through the smoke and firing back at the Japs were running across a soundstage. The smoke was from a smoke machine. The tank and the stage were in Hollywood, California, a place that has never been bombed, torpedoed, or strafed.

Teddy Brody loved it. He loved Leni Riefenstahl, John Ford, Blackton and Smith, and Mrs. Blackton too. He loved them for their audacity. There wasn’t enough reality around, so they made some up. Teddy had spent a lot of time in academic circles—B. A. from Yale Drama School, M. F. A. from UCLA—where facts were checked, where people were failed for inaccuracy and booted out for plagiarism, so he felt very tied to specific and literal truths and didn’t know how to escape them. Besides, his father had been such a liar—so adamant and violent about denying it—that it became very important to Teddy to keep precise score of who said exactly what, when they said it, when they changed it, and how they lied about it.

Center Screen went blank. Cut to black.

Victory in the West came up alongside Triumph of the Will. Hitler’s armies smashed through Belgium and Holland into France on Screen 2.

Hitler believed in the power of films. He destroyed entire cities for the purpose of creating images.56When the Wehrmacht went forth to conquer the world, every platoon had a cameraman, every regiment had its own PK, Propaganda Kompanie.57Hitler conquered continental Europe very quickly and with very little resistance. Part of the reason was that he convinced his enemies that the Thousand-Year Reich was invincible. He fought with the power of the mind. By the time the French troops faced the Nazis, they had seen the massed rallies at Nuremberg, they’d seen the result of blitzkrieg in Poland. They’d seen it on the same screen on which they’d seen Charlie Chaplin and Maurice Chevalier and newsreels that brought them the results of bicycle races.58

One by one, Beagle filled the screens with images of the enemy triumphant.

On the left the Nazis marched into Paris, conquered Yugoslavia and Greece, North Africa, and Ukraine, and the Baltic states. The Gestapo rounded up suspects and carted away Jews. They bombed innocent civilians in London.

Wake Island, the fall of Singapore and of the Philippines came up on Screens 4, 5, 9, and 10 as Japan marched forward (cowardly) and the Americans fell back (heroically). John Wayne watched the Bataan death march. The victors put the vanquished in brutal prison camps to languish and die.

Casablanca59came up on the Center Screen. To Beagle there was something defining about it. In the rhythm of the history he was creating, weaving, imagizing, it deserved to come out of the dark and be center-screen. It was the moment of choice—that’s what it was—when we went from selfish absorption to commitment. Everyone had come to Rick’s Café Americain; the refugees—Czech, German, Jewish, Rumanian, and more—Loyal French, Vichy French, a Russian, and the Nazis. And everyone’s fate was dependent on what Rick decided to do.

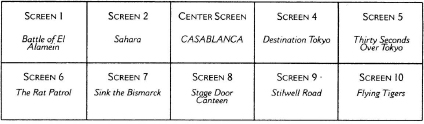

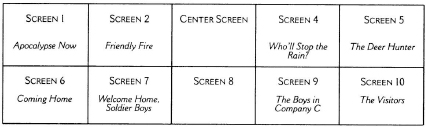

Once Rick decided, all the images changed.

became

By the end of Sahara, Bogart and his six guys, including Frenchie, a Brit, and a black Sudanese, had captured an entire company of previously invincible Nazis.

Over on the right the United States began to strike back in the Pacific.

After that, America was on a roll. There was no stopping it. It was half-real, half-myth, and the two were mixed shamelessly. The military gave Hollywood footage, advisors, equipment, soldiers, transport, cooperation. In return, the filmmakers gladly told the story that Washington and its soldiers wanted told, the way they wanted it told.

Center Screen—The Battle of San Pietro. The opening statement on the screen: “All the scenes in this picture were shot within range of enemy small arms or artillery fire.” Oddly enough, this was true. While all around the Center Screen men ran, leapt, dashed, charged into battle, the American soldiers fighting their way up the spine of Italy walked into battle.

Beagle wondered if the film affected him so because it was where his father had fought. Maybe not at San Pietro, but in Italy. Where he had been wounded. Every time he watched the footage and saw the men being carried away or waiting on the stretchers, he looked to see his father’s face. He never did, even with freeze-frames and digital enlargements. But he was sure that his father’s face must have looked like the faces in the film. So extraordinarily ordinary. Unshaven. Cigarette smoking. Dying for a cup of joe. Wishing for just one fresh vegetable, a bite of onion, a bath. His father was dead. He couldn’t ask him, “Dad, were you at San Pietro? Is that where you won your Purple Heart? Did you feel more for your country than I do? And can I somehow get there too? Was it better then? Was it as good as they make it seem in the movies?”

The men walked into the battle.

The film had been shot without sound. The director, Major John Huston, spoke the narration: “They were met by a wall of automatic-weapon and mortar fire. Volunteer patrols made desperate attempts to reach enemy lines and reduce strong points. Not a single member of any such patrol ever came back alive.”

Of all the hundreds of war films Beagle had watched, he considered this the best. It started with shots of barren fields and trees without fruit. It explained the battle, simply and clearly. It showed the fighting. It told what happened. “Sixteen tanks started down that road. Three reached the outskirts of the town. Of these, two were destroyed and one was missing.” It spoke of the casualties. “It was a very costly battle. After the battle the 143rd Infantry alone required eleven hundred replacements.” But the battle was finally won. The Germans retreated. The Italians, villagers and peasant farmers, came out of the caves where they’d been hiding. Huston showed the faces of the children and the old women. He said: “The new-won earth at San Pietro was plowed and sown and it should yield a good harvest this year. And the people pray to their patron saint to intercede with God on behalf of those who came and delivered them and moved on to the north with the passing battle.”

He let all the screens go black so that he could hear this ending.

Bang! They all snapped back on again. The planes were flying over Germany and against the Japanese. Real ones like Memphis Belle. Fakes ones like Memphis Belle, the feature film that had been made fifty years later about the documentary. Twelve O’Clock High. Victory Through Air Power (Walt Disney’s endorsement of bombing civilian targets), Flying Leathernecks (John Wayne). Bombardier, which showed that we need have no moral qualms about bombing cities—though that was one of the Nazis’ crimes—because our bombing was precise. How precise? The crewman says: “Put one in the smokestack.” There are three of them down there. Bombardier: “Which one?” Crewman: “Center one.” Bombardier: “That’s easy.”

The Center Screen’s gone black again. But underneath it, Screen 8, Donald Duck sings, “Heil, heil, right in the Führer’s face.” Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck fight the war. Bing Crosby sings for war bonds. Fred Astaire dances off to the Army. Gene Kelly dances off to war. Benny Goodman, Peggy Lee, Glenn Miller, Joe E. Brown, Bob Hope, and a lot of girls with breasts and legs whose names have been forgotten, Bette Midler in For the Boys, sing and dance and make that war, which was the good war, just a bit more of a fun war.

A wave of naval action sweeps across the screens. Lots of clips from Victory at Sea, the television documentary series, made from actual footage shot during the war. But then Charlton Heston and Henry Fonda walk right into the scenes.60

Center Screen. Next big plot point61—The Longest Day—D-Day.

Now the screens explode into action. Lots more color. Less black and white. More fun, less grim. The Dirty Dozen, Kelly’s Heroes, The Heroes of Telemark, Battle of the Bulge, The Bridge at Remagen, Operation Petticoat, Stalag 17, The Great Escape, War and Remembrance, The Guns of Navarone, Is Paris Burning?, Hell in the Pacific, Too Late the Hero, McHale’s Navy. Lots of stars, as if one of the secrets of the war was that they were all there, mixed in with the regular Joes.

Once again Beagle took all the other screens to black and returned to the center.

Once again Teddy was awestruck at how perfect the choice was.

The liberation of Paris. Real. Not staged. Spontaneous, not planned. An incredible moment, full of flowers and tears of joy, the pride of victory and women to kiss the victorious troops. They were images that made war worthwhile the way a baby’s smile suddenly buries the pain a mother has had in giving birth. It was the Paris of our dreams, the America of their hope.

FADE TO BLACK.

Pause. Rest. Korea. Those mean, barren hills. The snow. GIs in heavy overcoats, caps pulled down low under steel helmets. Unshaven. The gooney-bird stare. Americans beaten. Americans in retreat. Not many good films out of that one. Not many films at all, in fact. Men in War. Pork Chop Hill. All the Young Men. War Hunt. Documentary footage. Clips from MacArthur. Nothing on the Center Screen. All the images were small.

CUT TO: Vietnam.

News footage. In World War II most of the footage was shot by the armed forces. That meant they owned it and controlled it. In Vietnam it was shot by civilians. It was readily available and uncensored. Beagle filled up all the screens with the raw stuff of war.

Sound from Screen 2. A picture of a very ordinary-looking guy. “The first time that I knew I killed somebody was another incredible sense of power,” he says. “They were gooks, they weren’t like you and me. They were things.” This was a documentary. Frank: A Vietnam Veteran. “When you go out at dusk . . . and you set up and you’re quiet and you’re waiting, you are the hunter, you are the hunter. There’s this incredible, I mean incredible, sense of power in killing five people . . . the way I can equate it is to ejaculation. Just incredible sense of release: the I did this. I was very powerful. Everywhere I went, I had a weapon . . . I remember laying in bed, some woman on top of me, shooting holes in the ceiling. I mean really getting off on it. Where else, where else in the world did you have this kind of freedom . . . I was not Frank Barber, I was John Wayne, I was Steve McQueen, I was Clint Eastwood.”

Revelation. No one can stand that much reality.

CUT TO: Fiction. Born on the Fourth of July, 84 Charlie MoPic, Gardens of Stone, Go Tell the Spartans, Hamburger Hill, Platoon, A Rumor of War, Full Metal Jacket, Casualties of War. He left the Center Screen, the big screen, blank. A flat black hole. He let the images run over him. These were some damn good directors. Stone, Kubrick, De Palma, Coppola, Scorsese, Cimino, the best. He let himself feel. It was not good. Legless cripples. Lies and mendacity. Burning children. He wallowed in it. Drugs. Drug addicts, crazed veterans with guns. The fiction was more garish than the news, but the story was the same. Rapes. Double veterans.62Ambushes, booby traps, balls shot off. Burning huts.

Had it been that bad? Had all the ideals turned to madness and sadness. Had Americans become the Nazis. Occupying a foreign country. Taking reprisals on civilians. Lidice63become My Lai. It must have been the Luftwaffe flying those B-52s, doing to Hanoi what they did to Rotterdam and London.

No progress, just morass. No conquest, just despair. Troops defying their officers, killing their officers. And their officers, mechanical monsters without, apparently, a clue as to how to win this war. Bigger bombs and smaller results.

Beagle abruptly shut it all off.

There was more. But Beagle wasn’t ready to see it yet. Because it led inexorably to a conclusion? A call to action? A decision, after which he would have to come out of his room and face the world and find out if this time—at last—he had failed?

On the other side of the wall, Teddy Brody sat back, drained. He’d been watching this war shit for months now and he ought to have been immune to it. Certainly, he should have gotten over the shock of the Vietnam footage. He’d grown up post-Vietnam and come to consciousness during the period of revision that came so quickly after. By the time he was twenty, it somehow seemed that only the weirdos, the nutted-out, drugged-up, longhaired, rock ’n’ rolling reefer fuckers had been against the war. In conspiracy with TV guys to betray the noble warriors. A quick trip back in real time was too much reality. How did Americans go from John Wayne to that?

51 The Spanish-American War. If anyone remembers “Remember the Maine,” this is the war it came from. So did Teddy Roosevelt, the Rough Riders, and the Charge up San Juan Hill. The war was waged—America said—for the purpose of liberating Cuba. It’s a rather forgotten war, but it’s very interesting for a number of reasons:

1. It was a media-created war. Hearst and Pulitzer competed to create war fever because war sold papers. This was before television. Even before radio. So newspapers were not only influential, they were big business and made a lot of money.

2. It marks the beginning of the American Century. The U.S. took on a European power for the first time since being defeated by the British in 1812 and kicked the shit out of them. In the process:

3. The U.S. became a Two-Ocean Imperial Power, taking possession, from Spain, of the Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Spanish West Indies. Cuba became an independent territory under the protection of the United States.

4. The U.S. fought its first war against “native” guerrillas. It turned out that many Filipinos were not ecstatic that liberation from Spain meant possession by the United States.

52 “Although Germany had been defeated, Germany’s propaganda remained intact: Germans were the best soldiers in the world. American filmmakers accepted the idealized view of the German soldier and perpetuated it. Until the late 1970s, the Germans in American war movies are always clean shaven, with every button of their tunics neatly closed. And they never even flinch during battle.” (Jay Hyams, War Movies [Gallery Books, 1984])

53 Clyde Jeavons, A Pictorial History of War Films (Citadel Press, 1974). See also Hyams, War Movies.

54 Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception, trans. Patrick Camiller, Verso. “. . . the most startling aspect of the project was the creation of an artificial universe that looked entirely real and the resulting production of the first and most important example ever of an ‘authentic documentary’ of a pseudoevent. It is a stupendous revelation to realize that this whole enormous convention was primarily staged for the film.” (Amos Vogel)

“Preparations for the congress were fixed in conjunction with preliminary work on the film—that is to say, the event was organized in the manner of a theatrical performance, not only as a popular rally, but also to provide the material for a propaganda film . . . everything was decided by reference to the camera.” (Leni Riefenstahl)

55 John Ford directed the version that was released. An earlier and longer version was directed by Gregg Toland, a cameraman who worked with Ford frequently. Toland’s cut, critical of America’s unpreparedness, was not released (i. e., it was repressed, banned) until 1991. Toland is generally given credit for creating and filming the special effects that make up the actual attack sequence.

56 Most accounts state that the city of Rotterdam was leveled not as military necessity but as a demonstration to anyone who would dare oppose Nazi power, that is, to terrorize civilian populations and to paralyze the will of their enemies. The Germans filmed the destruction so that both friend and foe could see proof of the power of the Wehrmacht.

57 Virilio, War and Cinema. Hitler required the services of filmmakers and entertainers, but his greatest need was for those who could make the German people a mass of common visionaries “obeying a law they did not even know but which they could recite in their dreams” (Goebbels, 1931). Thus, while Roosevelt’s New Deal America was using radio and film to regulate the “war of the home market” and to restart the industrial-production machine, Hitler was directing the millions of unemployed Germans to relaunch war as an epic. Others would make war to win, but the German nation and its masters already moved in a world “where nothing has any meaning, neither good nor evil, neither time nor space, and where what other men call success can no longer serve as a criterion” (Goebbels).

58 “Lessons of Hitler’s rise to power were not lost on American leaders. The use of propaganda was an integral part of the Nazi strategy and seemed at least partly responsible for Hitler’s success.” Russell Earl Shain, An Analysis of Motion Pictures About War Released by the American Film Industry, 1930-1970 [Arno Press, 1976]).

A German general said early in the war that the opponent with the best cameras would be the victor, and the U.S. War Department responded by spending an annual sum of $50 million on factual filmmaking in order to swing the odds America’s way. Jeavons, A Pictorial History of War Films.

59 It’s entirely possible that there are people who don’t know the film Casablanca. It’s set on the eve of Pearl Harbor, actually released in 1943, the first big year for war films, when Hollywood delivered about 115 of them. The story, though not told in this order, is this: Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman) is married to Victor Lazlo (Paul Henreid), a hero of the underground from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia. Lazlo is sent to a concentration camp. Ilsa hears he is dead. She then meets Rick (Humphrey Bogart) in Paris. They fall in love. The Germans arrive. Ilsa and Rick are supposed to leave together. She finds out Victor is alive. She doesn’t show up. Rick leaves alone. He goes to Casablanca, where he opens a café and poses as a cynic. The town is run by a deliciously corrupt and genial policeman called Captain Renaud (Claude Rains). Victor and Ilsa and the Nazis all arrive. Rick gets to find out what happened in Paris, Ilsa is torn between love and duty. Rick must choose. He chooses to send Ilsa and Victor to safety together while he goes off to fight the fascists again. In the final scene he kills the head Nazi, Major Strasser (Conrad Veidt). This is witnessed by Captain Renaud—an official of the collaborationist Vichy government—who decides that it is time for him too to switch sides. He goes off with Rick. This is probably the best closing scene ever written. Woody Allen lovingly re-created it in Play It Again, Sam.

60 Midway, filmed 33 years later with Sensurround sound and wide-screen cinematography, mixes in original 16-mm footage. A lot of the footage shot in the Pacific was in color. Virtually all the footage shot in Europe was black and white.

61 Hollywood is currently very much into story structure. Books, treatments, and scripts are analyzed by readers in terms of plot points—points where the plot turns. Are there enough? Are they in the right place? Other important buzz words, if you’re planning to pitch, are backstory, inciting incident, progressive complications, setups and payoffs, subtext. These are courtesy of Robert McKee’s screenwriting seminar. Everyone, it seems, in the business who can’t write has taken McKee’s course to figure out what people who can write should be doing. McKee has never written a screenplay that anyone will actually produce. Back in 1988 he charged $600 for a weekend seminar, $350 for one of his staff to produce a reader’s report, $1,000 for a personal consultation on your script. So he makes quite a good living just for sounding off. There are lots of cute and ambitious young women in the audience, so presumably he gets laid a lot. And that, by almost everyone’s standards, is a pretty good definition of success.

62 Someone who had sex with or raped a woman and then killed her, common enough among American soldiers in Vietnam that there was a name for it.

63 Lidice, a village in Czechoslovakia, was totally destroyed on June 10, 1942, by Nazis in retaliation for the assassination by Czechs of Reinhard Heydrich, the deputy chief of the Gestapo and the number-two Nazi officer in Czechoslovakia. All men over sixteen were killed; the women and children were deported. Many Nazi atrocities were not known or acknowledged until the end of the war. Lidice, on the other hand, was publicized by the Germans as a lesson to others who might try to resist. It was the use of terror as a weapon. In those days terror was a weapon of the state, and what we call terrorism today was then the heroism of the resistance, of partisans, of the underground, our friends.

So the massacre of Lidice was known. It was regarded with singular horror. Yet the Germans spared women and children. The Americans in Vietnam did not. Perhaps the fact that Lidice was a common decision, a policy decision, and My Lai was an action led by a low-ranking officer in violation of official policy, more like a riot than a tactical choice, might make a difference to those who didn’t die there.