THE MIDDLE AGES AND THE RENAISSANCE IN EUROPE

SETTING THE STAGE FOR THE MIDDLE AGES

What happened after the collapse of the Roman Empire?

The Roman Empire collapsed for many reasons. One of the key reasons was the arrival of the tribal peoples, also called the Barbarians, who began carving up pieces of the Roman Empire. Over the centuries, these peoples, such as the Goths, the Vandals, the Franks, and the Anglo-Saxons, settled in Europe. In time, these peoples were all Christianized and then created kingdoms. These Christianized kingdoms became medieval Europe. Several important missionaries brought Christianity to these tribal peoples.

Why is Benedict important?

Benedict, often called St. Benedict, was born in 480 and died in either 543 or 547. He set up several monasteries in Italy. Most importantly, he wrote a guidebook on being a monk called the Rule of St. Benedict. His rule book became so influential that he is often called the founder of Western monasticism. One group of monks, called the Order of St. Benedict, are still around today.

However, Benedict did not invent Christian monasticism. Early Christian men and women living the monastic life existed in the second century. Famous monks, such as St. Antony and the Desert Fathers in Egypt, lived in the third and fourth centuries. By the time of Benedict, there were many Christian monasteries and a long history of Christian monasticism.

The Rule of St. Benedict is important because it became so influential. In writing his rule, Benedict tried to find a middle way of moderation. He wanted to avoid practices that were overzealous or fanatical, such as demands for extreme fasting. The problem with such practices is that they are very hard to maintain over the long term. On the other hand, Benedict wanted to avoid a monastic life that was too easy and that would encourage laziness and invite distractions from a life of prayer.

The motto of St. Benedict was ora et labora, which means “pray and work.” Monks were required to spend most of their time in prayer either in community or by themselves. Yet, monks were also required to work to support themselves. Initially, Benedict imagined monks supporting themselves through manual labor and farm work. He wanted to get away from monasteries that were supported solely by donations.

He expected his monks to live a simple life without possessions for fear that possessions would distract them from the spiritual life and also because more possessions would require more money to buy them.

Who are some important Christian missionaries of this period?

St. Augustine of Canterbury (d. 604) brought Christianity to England. He is a different person from Augustine of Hippo (354–430). St. Boniface (c. 675–754) brought Christianity to the Germanic tribes. One legend tells how he chopped down the sacred tree of Thor (called Donar in German) in a village. When he was not struck dead by lightning, the villagers believed his god was more powerful than Thor, so they converted.

St. Cyril (826–869) and St. Methodius (815–885) were two brothers who are known as the “apostles to the Slavs” for their missionary work with the Slavic people in Eastern Europe. They created a special alphabet for translating the Bible. Called the Cyrillic alphabet, it is named after Cyril. Today, the script is used for languages such as Russian.

Who was Saint Patrick?

Saint Patrick is known as the “Apostle of Ireland” for helping to bring Christianity to Ireland. He lived in the late 400s. He grew up in Great Britain but was captured by Irish pirates at about the age of sixteen. He worked as a slave for the next six years until he escaped to his family in Britain. He became a priest and returned to Ireland as a missionary. He eventually became a bishop. He is remembered for bringing Christianity to Ireland.

A statue of Charles Martel can be found at Versailles. His victory at the Battle of Tours helped halt Muslim expansion into Europe.

Why is the shamrock the symbol of St. Patrick?

There is a legend that Patrick used the shamrock to teach people about the Trinity. Just as the shamrock has three leaves, the Trinity has three persons in one God. However, since the legend first appears in writing in the 1700s, there is serious doubt whether Saint Patrick actually used the shamrock as a teaching device.

The feast of Saint Patrick is March 17. Many people use shamrocks as decorations to remember Saint Patrick, especially in areas that have populations with an Irish heritage. Ironically, many bars decorate with shamrocks as people celebrate St. Patrick’s Day by drinking, with little interest in the religious beliefs supposedly behind the symbol.

Who was Gregory the Great?

Gregory lived from c. 540 to 604 and became the bishop of Rome in 590. He did much to shape the influence and authority of the bishop of Rome over Western Christianity, which included his efforts to send out missionaries in Europe. He is called Pope Gregory I, although the word “pope” was not in use in his time for the bishop of Rome. His numerous writings have survived, including his sermons and letters. The Gregorian chant, a style of music used by monks for chanting the Psalms from the Bible, is named after him.

Later, in the Middle Ages, the pope in Rome would become a key figure in religion and politics in Europe for many centuries.

Who was Charles Martel?

In 719, Charles Martel (c. 688–741), known as Charles the Hammer, united the lands of the Franks under his rule. He is most famous for his victory at the Battle of Tours in 732 in which he defeated a Muslim army led by Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi coming from the area that today is Spain.

Although some see this battle as key in stopping Islam from overtaking more of Europe, there is much uncertainty about the exact location of the battle, the size of the armies, and the significance of the battle.

THE MIDDLE AGES

When is the beginning of the Middle Ages?

There are different views on when to mark the beginning of the Middle Ages. A common beginning point is the fifth century with the decline of the Roman Empire. Although in the past, the term “Dark Ages” was often used for the period between the Roman Empire and medieval Christian Europe, the term is avoided today. The Middle Ages is also called the Medieval Period.

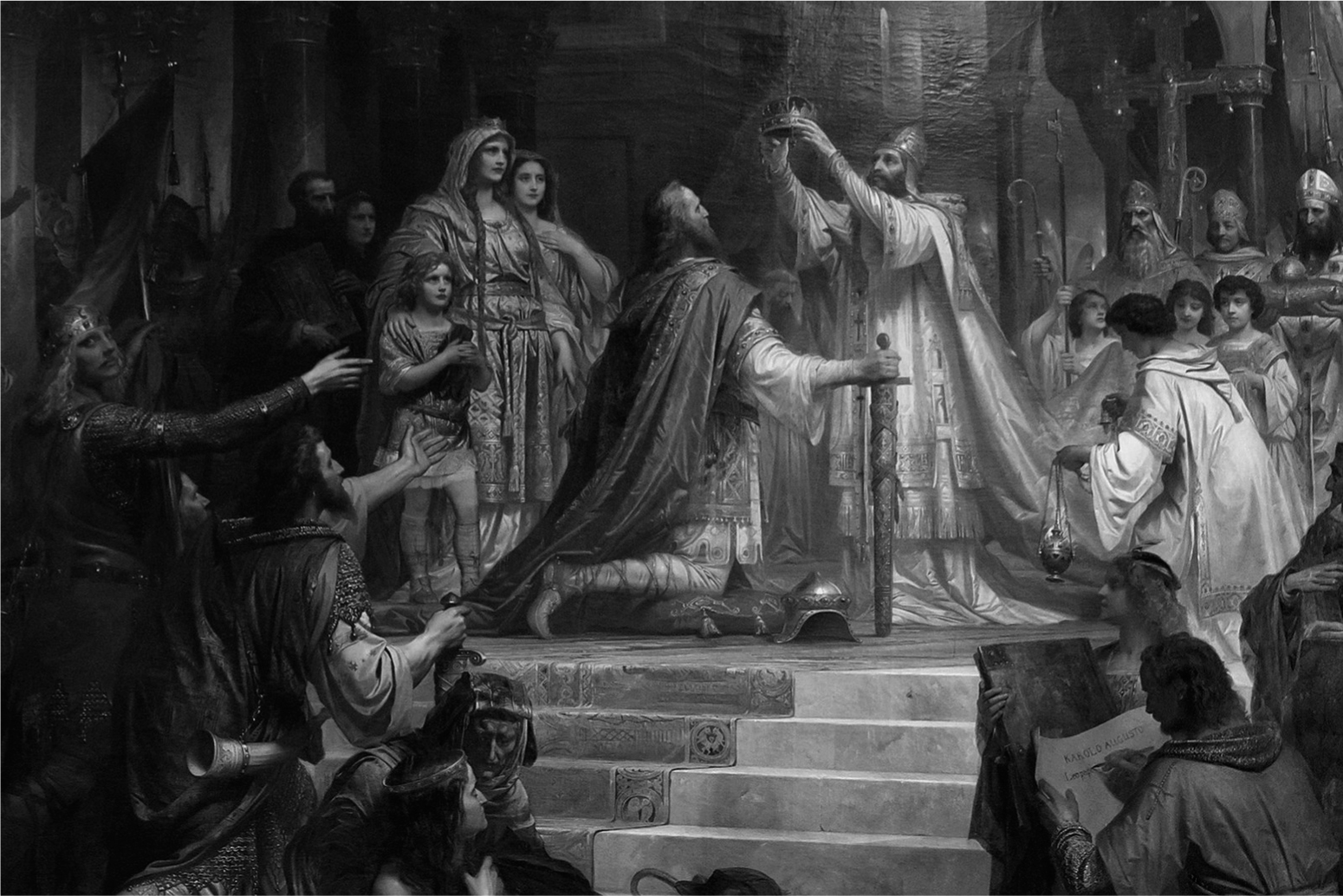

The year 800 marks an important year in the early Middle Ages. In that year, the king of the Franks, Charlemagne, was crowned the holy Roman emperor by Pope Leo III. The pope wanted to recreate an empire on the model of the old Roman emperor, only this time, it would be a Christian empire. Charlemagne did create a large kingdom that would include what are known today as France, Germany, and part of Italy. However, the Holy Roman Empire never lived up to its name. It was very small compared to the original Roman Empire. It was not that Roman, and although Charlemagne and the succeeding rulers were Christians, their conduct was often anything but holy.

However, the title and role of the holy Roman emperor would last in Europe through 1806. Over the centuries, the holy Roman emperors, who would be French, Spanish, and German, would have great influence over what happened in Europe.

Who was Charlemagne?

Charlemagne (742–814), or Charles the Great, became king of the Franks after his father, Pepin the Short (c. 714–768, son of Charles Martel), and his brother died. Charles then began expanding his kingdom. He sometimes employed brutal tactics in bringing people and regions under control, such as mass executions to subdue Saxon rebellions.

In Latin he was called Carolus Magnus, which means Charles the Great. (Carol, Carl, and Charles are related names. The empire of Charles is called the Carolingian Empire, and the time frame is the Carolingian Period.) As a patron of the arts, literature, and science, Charlemagne revived Western Europe after the decline of the Roman Empire.

The 1861 painting by Friedrich Kaulbach titled Imperial Coronation of Charlemagne reverentially depicts the Frankish king being crowned emperor of the Romans in 800 by Pope Leo III.

How did people in the Middle Ages see the world?

To better understand this period, one must note that most people, but not all, thought the world was flat. They also thought that the sun, moon, and stars were small objects a few miles up in the air. Most people had no idea that Earth was a planet in a vast, vast universe. So, most people believed Heaven was “up there, beyond the stars” and that Hell was down below Earth. By the Middle Ages, the concepts of Heaven and Hell were well developed.

During the Middle Ages, scholars argued that the meaning of life on Earth lay primarily in its relation to an afterlife. Therefore, they believed that art for its own sake had no value, and they even frowned on the recognition of individual talent. For this reason, many of the great artworks of the Middle Ages were created anonymously.

What are the characteristics of medieval times?

Although the Middle Ages were shadowed by poverty, ignorance, economic chaos, bad government, and the plague, it was also a period of cultural and artistic achievement. For example, the university originated in medieval Europe (the first university was established in 1158 in Bologna, Italy). The period was marked by the belief, based on the Christian faith, that the universe was an ordered world, ruled by an infinite and allknowing God. This belief persisted even through the turmoil of wars and social upheavals, and it is evident in the soaring Gothic architecture (such as the Cathedral of Chartres, France), the poetry of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Gregorian chant, and the music of such composers as Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377).

What was the structure of feudal society?

With the breakup of the Roman Empire, a system called feudalism developed. What follows is a simplified description of the feudal social structure. It was often more complicated than this and often varied from place to place.

Kings—At the top was the king. In theory, all the land in the kingdom was his. He would then give or lease large sections of the land to men called lords or barons.

Lords—The land of each lord was called a manor. In exchange for land, the lord had to serve in the royal court and provide knights for the king. Lords gave some of their land to knights. Lords were wealthy landowners during the Middle Ages, and their manors were self-sufficient estates. The lord would lease land to peasants who would farm it; in return, the peasants would pay the lord in taxes, in services, or in kind (with crops or goods). In addition to farmland, a manor would typically have meadows, woodlands, and a small village. The lord presided over the entire manor and all the people living there. As the administrator of the land, he collected taxes and presided over legal matters. But the manors were not military entities; in other words, the lord did not promise protection to the peasants living on his land. As such, the manors were purely socioeconomic (as opposed to fiefs, which were social, economic, and political units).

Knights—Knights were warriors who were typically given land by a lord in exchange for promises to protect the lord, his family, and the lord’s manor.

Serfs—At the bottom were the serfs, also called villeins. They had to provide the lord with labor and food. They had few rights. They were bound to the manor and could not leave without the lord’s permission. They even had to have the lord’s permission to marry. Serfs lived lives of hard work and poverty.

Slaves—In a number of places, slaves also existed.

What were fiefs?

A fief was an estate that a lord owned, governed, and protected. A fief consisted of several manors (each of which might have had its own lord) and their villages, along with all buildings on the land as well as the peasants (serfs) who worked the land, served at court, or took up arms on behalf of the lord. The lord of the fief, called a feudal lord, would secure the allegiance of the manorial lords (sometimes called seigniors), who would in turn secure the allegiance of the peasants.

In short, land was exchanged for loyalty; this was feudalism, the political and economic system of the Middle Ages. The word “feud” is of Germanic origin and means “fee”; in repayment for the land they lived on and the protection they received from the lord, serfs were expected to pay the lord fees—in the form of money (taxes), services, or goods.

What were vassals?

In the Middle Ages, a vassal was anyone who was under the protection of another and therefore owed and avowed not only allegiance but a payment of some sort to their protector. Peasants (serfs and village commoners) were always vassals to a lord—whether it was the lord of the manor or the lord of the fief. But the lord of the manor was himself a vassal—to the lord of the fief. As kingdoms were created, with many fiefs within their jurisdiction, the feudal lords became the vassals of the kings.

MONASTICISM

What is monasticism?

Monasticism is the life of monks living in monasteries devoting their lives to prayer.

Did Christians invent monasticism?

Christians did not invent monasticism. Buddhist monks had been living the monastic life for 500 years before Jesus. The monastic tradition in Hinduism is even older.

There do not seem to be many monks around today.

Why was it important? Although monks and monasteries are few and far between today, for most of Christian history, monasteries were extremely important. In the Middle Ages, there were thousands of monasteries all across Europe from small ones of a dozen or so men to enormous monasteries with hundreds of men. Monasteries served both religious and societal functions in their time. For example, in many families, the eldest son would alone inherit the family farm because if the land were divided among all the sons, the pieces each had would be too small to farm. After the eldest son got the family land, what would happen to the younger sons? One answer was to send them to monasteries.

Monks and monasteries were once common throughout Europe, but where once there were thousands of them, today, there are just a couple hundred Trappist and Benedictine monasteries.

What is the monastic life?

To understand the monastic life, one must start by recognizing that this tradition came from a view of God as harsh and demanding. The culture that supported the monastic life saw the Christian life as very difficult. If one wanted to follow Christ completely, then one had to withdraw from ordinary life and devote oneself to prayer.

Also, keep in mind that effective birth control is a modern reality, so becoming celibate and giving up sex freed one from all the demands of having and raising children. This freed one up to follow God completely. It is sometimes difficult for modern people to appreciate the reasons for celibacy.

Monks were not married. Mono in Greek means “one,” and from this comes the word “monk.” Monks were alone in terms of not being married, although they usually lived in communities with other monks. A monk lives in a “monastery.” A monk lives a “monastic” life. The head of a monastery is called the “abbot.” This comes from the word for father, “abba.” Sometimes, a monastery is called an “abbey.”

Women who wanted to follow the monastic life lived in monasteries for women called “convents.” They were called “nuns.” The head of a convent was called “Mother Superior.” She might also be called an “abbess.” For both men in monasteries and women in convents, they lived a life closed off from the outside world in what is called a “cloister.”

In London many centuries ago, there was an abbey. The road in front of it was called Abbey Road. The recording studio for the Beatles was on Abbey Road, so the Beatles named one of their famous albums Abbey Road.

To become a monk, a man took three vows. (A vow is a promise.) The three vows were celibacy (no marriage and no sex), poverty (to not own anything), and obedience (to the abbot). In a monastery, most men were not priests and called each other “brother.” A few became priests, and they would be called “father.”

Nuns took the same vows, although the first vow was called “chastity.” The nuns called each other “sister,” although the leader of the convent was often called “mother.”

What did the monks do?

The most important duty of the monks and sisters in convents was to pray. The sequence of prayers was called the Divine Office. Eight times during the day and night, monks and nuns went to the chapel to pray with their community. Two passages from Psalm 119 were cited for determining the number of times to pray during a twenty-four-hour period: “At midnight I rise to praise you because of your righteous judgments” (v. 62) and “Seven times a day I praise you because your judgments are righteous” (v. 164, NABRE).

The traditional times of prayer were as follows:

• Midnight, called Matins, Vigils, Nocturns, or the Night Office. (The French word matin means “morning.”)

• Lauds or Dawn Prayer at Dawn, or 3 A.M. (“Lauds” is based on the Latin word for praise.)

• Prime or Early Morning Prayer at the First Hour, typically at 6 A.M.

• Terce or Mid-Morning Prayer at the Third Hour, typically at 9 A.M.

• Sext or Midday Prayer at the Sixth Hour, typically at 12 noon.

• None or Mid-Afternoon Prayer at the Ninth Hour, typically at 3 P.M. (The words “prime,” “terce,” “sex,” and “none” are based on the Latin words for first, third, sixth, and ninth hours of the day.)

• Vespers or Evening Prayer, typically at 6 P.M.

• Compline or Night Prayer, typically at 9 P.M.

The core prayers of the Divine Office were the Psalms. At each prayer time, one or more of the Psalms was chanted. Often, they were chanted in choir style, with one side of the chapel or church saying one line of the psalm with the next line chanted by the other side of the chapel. It went back and forth from one side to the other until the psalm was completed.

The Canticle of Zachariah, also called the Benedictus, from the Gospel of Luke was usually chanted during morning prayers; the Canticle of Mary, called the Magnificat, also from the Gospel of Luke, was chanted at Vespers. Typically, the Psalms would be chanted as music. The most common style of monastic music was called a Gregorian chant.

MEDIEVAL LITERATURE AND ARCHITECTURE

What is the famous book about the afterlife written by Dante in the Middle Ages?

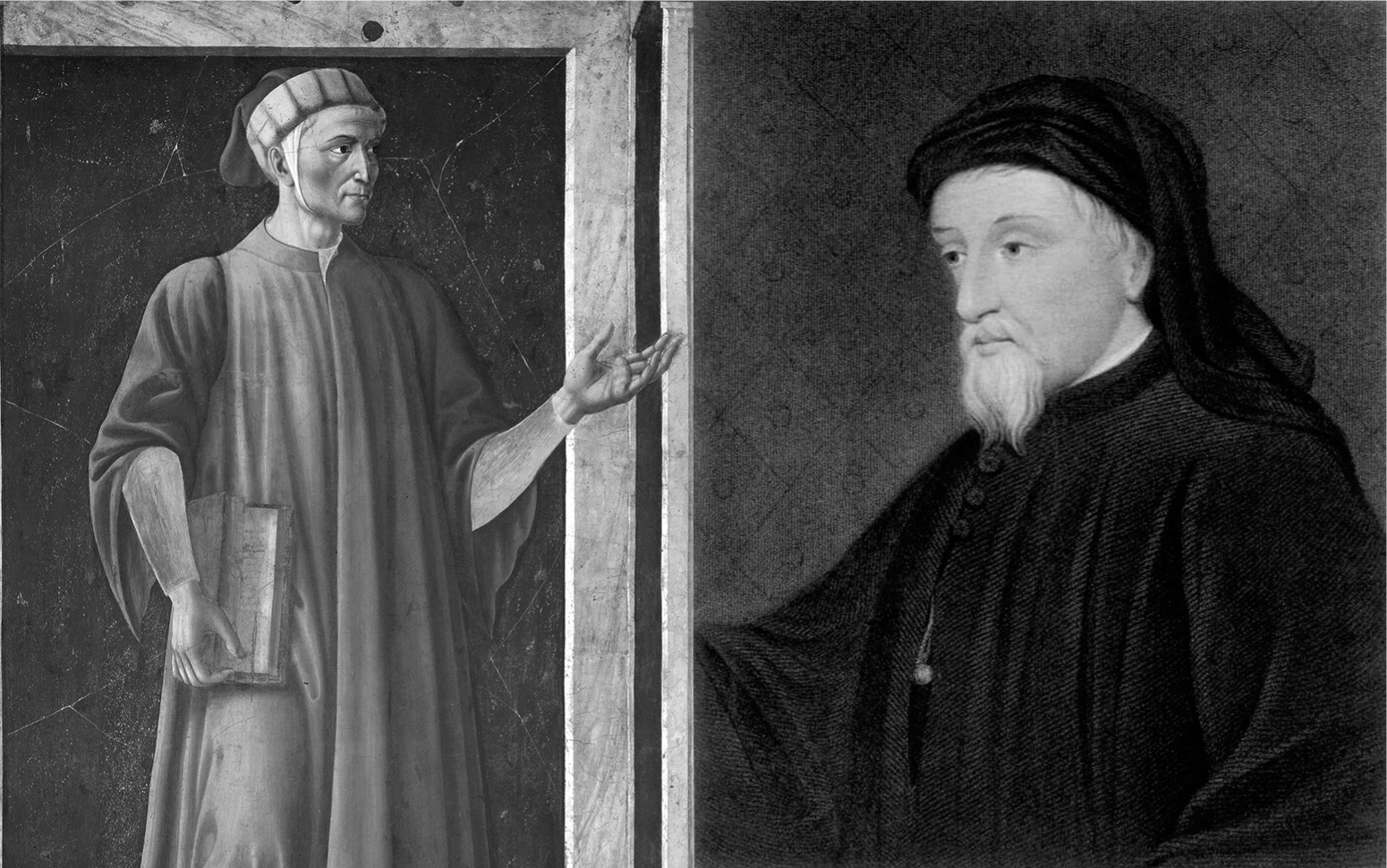

The Italian writer Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) wrote The Divine Comedy, describing the medieval view of the afterlife. The word “comedy” does not mean it is a humorous story but rather that it has a happy ending. The Divine Comedy is a poem made up of 100 parts called “cantos,” which are divided into three sections: Inferno—Hell, Purgatorio—Purgatory, and Paradiso—Paradise or Heaven.

In the poem, Dante is led through Hell and Purgatory by the Roman writer Virgil. Beatrice, Dante’s image of the ideal woman, leads him through Paradise.

What is The Canterbury Tales?

The Canterbury Tales was written by Geoffrey Chaucer between the years 1387 and 1400. The book is a collection of stories told by pilgrims on their way to the shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury, England. The Canterbury Tales gives a window into the late medieval feudal world. A number of the characters are religious figures, such as the Parson, the Monk, the Friar, the Pardoner, the Summoner, nuns, priests, and the Prioress (a woman in charge of a convent). The characters are all introduced in the Prologue.

Two of Europe’s most famous authors are Dante Alighieri (left), who composed The Divine Comedy, and Geoffrey Chaucer, author of The Canterbury Tales.

Chaucer did not write about ideal models of these various religious roles. Rather, he describes monks and friars who are ignoring the precepts of their religious orders. Chaucer does this because they make for more interesting characters. A monk or friar who followed the rules and spent all his time praying would actually be quite boring.

Some of the more popular tales are “The Miller’s Tale,” “The Reeve’s Tale,” “The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” and “The Pardoner’s Tale.” Although Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales in English, he used a much older form of English that modern readers find difficult to read. Chaucer also wrote in verse style. So, rather than read the original, most readers today prefer a prose version in modern English. (Verse is short lines, such as in a poem. Prose is in the form of paragraphs.)

What are the Gothic cathedrals?

About a hundred Gothic cathedrals were built in Europe in the Middle Ages. The Gothic style includes pointed arches, extensive use of stained glass, and flying buttresses to support the wall. The Gothic movement began with the Church of St. Denis outside of Paris. The leader of this church, Abbot Suger (1081–1151), had been influenced by the writings of an early Christian monk named Pseudo-Dionysius, who saw light as God’s essence. Suger wanted to open the church walls to include lots of window space for colorful, stained glass windows. The trick was to design buttresses in the walls to hold up the roof and ceiling of the cathedral. The buttresses held the weight, which meant the walls could be opened up for glass.

Do an image search for “St. Denis Paris,” and then a search for “flying buttresses.” Two of the most famous Gothic cathedrals are Notre Dame in Paris and Chartres Cathedral in the town of Chartres, France. Take a look at them online. Notre Dame suffered a devastating fire in 2019, though it is being restored.

THE CRUSADES

What were the Crusades?

The Crusades were a series of military campaigns in the Middle Ages undertaken by European Christians to conquer the Holy Land—Jerusalem and the surrounding territory. At that time, various Muslim rulers held the area. The First Crusade began in 1095. The last Crusade ended in 1272.

The First Crusade conquered Jerusalem but with great bloodshed. The Muslims then retook Jerusalem, and subsequent Crusades failed to reconquer it. By 1291, all the territory that had been conquered during the Crusades was in Muslim hands.

A statue of Saladin at the Egyptian Military Museum in Cairo shows the sultan who created an empire that spanned Egypt, Syria, Upper Mesopotamia, Yemen, western Saudi Arabia, and northern Africa.

What happened in the First Crusade?

The First Crusade lasted from 1095 to 1099. In response to the letter of Emperor Alexius, Pope Urban II, in an open-air sermon in Clermont, France, called for a crusade on November 27, 1095. He wanted an army to rescue the Holy Land. He gave exaggerated accounts of Muslim atrocities against Christians. He offered pardon of sins for those on the crusade and freedom from their debts. Part of the motivation for Pope Urban was his hope that a crusade would unite the Christian kingdoms in Europe and stop the fighting between them.

In the wake of the Crusaders’ conquest of so much territory, including Jerusalem, the Muslims started organizing to fight back. The Muslims’ first step in 1144 was to reconquer the city of Edessa (today in modern Turkey), which the Crusaders conquered on their way to Jerusalem.

What happened in the Second Crusade?

The Second Crusade lasted from 1147 to 1149. In response to the fall of Edessa, Pope Eugene III called for the Second Crusade. The pope commissioned the fiery Bernard of Clairvaux to preach the crusade and build up support. Kings Conrad III and Louis VII led the Crusader army. There was dissension and distrust among the various Christian armies. They decided to attack the city of Damascus even though the city was an ally of Jerusalem, which the Crusaders held. Although they laid siege to Damascus, the Crusaders eventually gave up and went home. The whole crusade was a debacle.

What happened after the Second Crusade?

The Muslim ruler Saladin came to power. In 1187 he conquered Jerusalem. He then destroyed much of the Crusader states.

What happened in the Third Crusade?

The Third Crusade lasted from 1187 to 1192. It was led by German emperor Frederick I (Frederick Barbarossa), King Philip II of France, and King Richard I of England, the Lionheart. Frederick drowned en route. Richard and Philip conquered the city of Acre, which is today in northern Israel. Richard made a deal with Saladin: Richard could rebuild the Crusader states, but Jerusalem remained under Saladin’s control. The story of Robin Hood in England takes place while Richard is on this crusade.

What happened in the Fourth Crusade?

The Fourth Crusade lasted from 1202 to 1204. It was led by Count Baldwin. To get the city of Venice to pay for the ships he needed, he agreed to attack the Christian city of Zara, a trade rival of Venice. The Crusaders then attacked the Christian city of Constantinople. They looted and sacked the city in 1204.

What is the legacy of the Fourth Crusade?

The sacking of Constantinople greatly weakened it so that it would eventually be taken over by the Muslim Ottoman Turks in 1453. Ironically, defending Christian Constantinople and its surrounding territory had been the original catalyst for starting the Crusades.

The sacking of Constantinople led to great resentment on the part of Eastern Orthodox Christians toward Roman Catholic Christians. In some places the resentment still lingers. For many people today, the Fourth Crusade is one of several important illustrations of the fundamental immorality and unchristian nature of the Crusades.

What was the Fifth Crusade?

This crusade, which lasted from 1217 to 1221, was called by Pope Innocent III and led by King John of Jerusalem. His army sailed to Egypt to move toward Jerusalem from the west. The Crusaders conquered the Egyptian city of Damietta. At this point, the sultan, fearing the Crusaders, offered them the city of Jerusalem. However, the pope’s representative, Cardinal Pelagius, overruled John and insisted that they attack Jerusalem.

The Crusader armies had to wait for more troops to arrive. In the meantime, the army was destroyed by floods on the Nile and the Egyptian army. The crusade was a failure.

What was the Children’s Crusade of 1212?

The story of the Children’s Crusade is a mix of legend and fact, with no one sure what exactly happened. The legend is that a large band of children, perhaps 30,000, set out to free the Holy Land. They were assuming that the Muslim armies would surrender Jerusalem to a band of peaceful children. When the children arrived at the Mediterranean Sea, they were offered passage on ships. However, they were sold into slavery instead.

The historical evidence points to two groups of peasants of all ages. Both set out, but both groups fell apart before leaving Europe.

This crusade, which lasted from 1228 to 1229, was led by German emperor Frederick II. Frederick did not want to go on a crusade but was forced by Pope Innocent III. Once he got to the Holy Land, Frederick made a deal with the Muslims, called the Treaty of Jerusalem, and got control of Jerusalem. However, neither the Christians nor the Muslims liked the deal. Frederick eventually left and returned to Europe to protect his kingdom back home. In 1244, the Muslims retook Jerusalem.

What was the Seventh Crusade?

This crusade, which lasted from 1248 to 1254, was led by King Louis IX, who would later become St. Louis. (The well-known city in Missouri is named after him.) Louis IX conquered the Egyptian city of Damietta. However, he was then captured. He paid a large ransom for his freedom and then returned with his forces to France.

What was the Eighth Crusade?

This crusade, which occurred in 1270, was also led by King Louis IX. The plan was to take North Africa and then conquer Jerusalem. It failed, and King Louis died of the plague in North Africa.

What was the Ninth Crusade?

This crusade, which lasted from 1271 to 1272, was led by Prince Edward of England and achieved nothing. Some historians list it as a second phase of the Eighth Crusade. In the next years, Muslim armies conquered all Crusader strongholds in what had been the Crusader states. The last to fall was the city of Acre in 1291.

What is the legacy of the Crusades today?

When people today make the claim that most wars have been fought over religion, the Crusades become their primary example. The truth is that most wars are fought over political and economic issues.

However, the Crusades illustrate a problem that has occurred many times over the centuries when religion is used to promote very unreligious policies. A recent example is the 1995 genocide by Christian Serbians of Muslims from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Crusades also played an important role in creating friction between some Muslims and some Christians, which is still around today. However, the big source of resentment by some Muslims of the Mideast toward Western countries has to do with the economic, political, and military domination of many countries of the Mideast by both the British and then the Americans in the twentieth century. For example, in the Mideast, Britain and America have been involved in the overthrow of governments in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Egypt. Most Americans do not know this history, but people in the regions do.

What is the Magna Carta?

The Magna Carta, one of the most famous documents in British history, was signed by King John (1167–1216) in June 1215. He had been forced to sign it. Drawn up by English barons who were angered by the king’s encroachment on their rights, the charter has been credited with no less than ensuring personal liberty and putting forth the rights of the individual, which include the guarantee of a trial by jury: “No freeman shall be arrested and imprisoned, or dispossessed, or outlawed, or banished, or in any way molested; nor will be set forth against him, nor send against him, unless by the lawful judgment of his peers, and by the law of the land.”

An 1875 illustration by John Leech shows King John II refusing to sign the Magna Carta when it was first presented to him.

The document, to which John was forced to put his seal, asserted the rights of the barons, churchmen, and townspeople and provided for the king’s assurance that he would not encroach on their privileges. In short, the Magna Carta stipulated that the king, too, was subject to the laws of the land.

The Magna Carta had a provision for a Great Council, to be comprised of nobles and clergy, who would approve the actions of the king and ensure the tenets set forth in the charter were upheld. It is credited with laying the foundation for a parliamentary government in England.

After signing it, John immediately appealed to Pope Innocent III (1160 or 1161–1216), who issued an annulment of the charter. Nevertheless, John died before he could further fight it, and the Magna Carta (which means “Great Charter”) was later upheld as the basis of English feudal justice. It is still considered by many to be the cornerstone of constitutional government.

RELIGIOUS STRUGGLES IN THE MIDDLE AGES

What was the Investiture Struggle?

Also called the Investiture Controversy, it is the name for the power struggle between kings and popes over who got to select bishops and abbots—the heads of monasteries. The pope wanted to choose all the bishops and abbots in Europe, whereas kings wanted to choose the bishops and abbots in their lands so they could pick clergy who would support their political and economic policies. At that time, bishops and abbots were often influential because they controlled large tracts of land and had economic and political influence.

The struggle for supremacy peaked in 1075, when Pope Gregory VII (c. 1020–1085), who wanted to protect the Church from the influence of Europe’s powerful leaders, issued a decree against lay investitures, meaning that no one except the pope could name bishops or heads of monasteries. (A king was not a member of the clergy and was thus a layperson. Investiture is the process of choosing and installing an abbot or bishop.) German king Henry IV (1050–1106), who was fighting for political power, took exception to Gregory’s decree and challenged it, asserting that the kings should have the right to name the bishops. The pope excommunicated Henry. Though he later sought—and was granted—forgiveness by Gregory, the struggle did not end there. Henry soon regained political support, deposed Gregory (in 1084), and set up an antipope (Clement III), who in turn crowned Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor

What was the Great Schism?

For some centuries, tension had been growing between Western Christianity under the leadership of the pope in Rome and Eastern Orthodox Christianity. A key issue was that the Eastern Christians did not believe that the pope was the head of the universal church. Also, there was a controversy over a word added to the Latin version of the Nicene Creed. There was also much misunderstanding between the two sides.

The Eastern Orthodox Church came about because of the Great Great Schism, when the pope in Rome split with leader of the church in Constantinople.

In 1054, things came to a head when Pope Leo IX excommunicated Patriarch Michael Cerularius (the head bishop) of Constantinople. Cerularius responded by excommunicating the pope. This break between the Western and Eastern Christian churches is called the Great Schism or the East-West Schism. (The word “schism” refers to a break or division, especially within churches.) These two branches of Christianity have remained divided up to the present. However, starting in the midtwentieth century, many efforts have been made to promote respect and understanding between them.

The Western part became the Roman Catholic Church. The Eastern part became the Christian Orthodox churches, which today are usually identified by nationality, such as the Greek Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox Church, and the Orthodox Church in America.

What was the Filioque Controversy?

The Latin Church added the word “filioque” to the Nicene Creed. The word means “and the Son” and was used in the sentence: “We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son.” The Eastern Orthodox Church insisted that the Creed only described the Holy Spirit as proceeding from the Father. This disagreement is known as the Filioque Controversy.

What was the place of Jews in the Middle Ages?

Jews played an important role in medieval Europe. Jews increased in numbers, although they were a minority of the overall population. The dominant Christian culture tolerated Judaism because of the Jewish background of Jesus. However, there were many laws and restrictions against Jews. For instance, Jews were often forbidden from owning property or belonging to the guilds, the equivalent of labor unions.

In some places, Jews were required to wear clothes that identified them as Jews. Sometimes, they were required to wear yellow stars. In some cities, Jews were required to live in specific areas called ghettos. Also, under penalty of death, Jews were forbidden to convert Christians to Judaism.

In many places, there was significant anti-Semitism, which occasionally flared up into violence. During the Crusades, peasant armies massacred Jews in several cities.

Is there a connection between Jews and banking that developed in this period?

In several passages in the Bible, the lending of money at usury is forbidden. Usury is to charge interest, so technically, Christians were forbidden from charging interest on loans. However, Jews understood this rule to mean that Jews could not lend money to other Jews at interest. However, they could lend to non-Jews, so by this quirk in interpreting this rule of the Bible, some Jews found themselves as moneylenders in the medieval world. The problem was that in the growing economies of the Middle Ages, no one was willing to lend money unless there was some interest to cover the risk for lending the money.

Keep in mind that in the Middle Ages, no consumer-protection laws existed. Many people today are not great at figuring percentages; most people in the Middle Ages could not do math. Not surprisingly, there was often mistrust and anger toward Jewish moneylenders, in some cases legitimate and in other cases not legitimate.

Today, modern Christians get around the biblical prohibition on lending money at usury by saying that usury means exorbitant interest rates. Although this is a helpful way around the issue, it ignores the original Bible intent that all charging of interest was forbidden.

Why is the Renaissance considered a time of rebirth?

The term “renaissance” is from the French word for “rebirth,” and the period from 1350 to 1600 C.E. in Europe was marked by the resurrection of ancient Greek and Roman ideals; the flourishing of art, literature, and philosophy; and the beginning of modern science. (Ancient Greek and Roman cultures are called “classical.”) However, the “Renaissance” label was given to this period many centuries later.

Italians believed themselves to be the true heirs to Roman achievement. For this reason, it was natural that the Renaissance began in Italy, where the ruins of ancient civilization provided a constant reminder of their classical past and where other artistic movements, such as Gothic, had never taken firm hold.

How did the Renaissance begin?

In northern Italy, a series of city-states developed, including Florence, Rome, Venice, and Milan, that gained prosperity through trade and banking, and as a result, a wealthy class of businessmen emerged. These community leaders admired and encouraged creativity, patronizing artists who might glorify their commercial achievement with great buildings, paintings, and sculptures. The most influential patrons of the arts were the Medicis, a wealthy banking family in Florence. Members of the Medici family supported many important artists, including Botticelli and Michelangelo. Guided by the Medici patronage, Florence became the most magnificent city of the period.

Florence, Italy, is considered the birthplace of the Renaissance, a time of cultural revitalization. after the long, difficult Dark Ages.

One way that patrons encouraged art was to sponsor competitions in order to spur artists on to more significant achievement. In many cases, the losers of these contests went on to greater fame than the winners. After his defeat in the competition to create the bronze doors of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) made several trips to take measurements of the ruined buildings of ancient Rome. When he returned to Florence, he created the immense il duomo (dome) of the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral, a classically influenced structure that became the first great monument of the Renaissance.

How is the attitude of the Renaissance characterized?

The artists and thinkers of the Renaissance, like the ancient Greeks and Romans, valued earthly life, glorified man’s nature, and celebrated individual achievement. These new attitudes combined to form a new spirit of optimism, the belief that man was capable of accomplishing great things.

This outlook was the result of the activities of the wealthy mercantile class in northern Italy, who, aside from supporting the arts and letters, also began collecting the classical texts that had been forgotten during the Middle Ages. Ancient manuscripts were taken to libraries, where scholars from around Europe could study them. The rediscovery of classical texts prompted a new way of looking at the world.

As mentioned before, during the Middle Ages, scholars had argued that the meaning of life on Earth lay primarily in its relation to an afterlife. Therefore, they believed that art for its own sake had no value, and they even frowned on the recognition of individual talent. In contrast, Renaissance artists and thinkers studied classical works for the purpose of imitating them. As an expression of their new optimism, Renaissance scholars embraced the study of classical subjects that addressed human concerns. These “humanities,” as they came to be called, included language and literature, art, history, rhetoric, and philosophy.

Above all, humanists, those who espoused the values of this type of education, believed in humankind’s potential to become well versed in many areas. During this era, people in all disciplines began using critical skills as a means of understanding everything from nature to politics. Today, a person who is knowledgeable in many fields is called a “Renaissance man” or “Renaissance woman.”

Which artists and thinkers are considered the greatest minds of the Renaissance?

The great writers of the Renaissance include the Italian poet Petrarch (1304–1374), who became the first great writer of the Renaissance and was one of the first proponents of the concept that a “rebirth” was in progress; Florentine historian Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), who wrote the highly influential work The Prince (1513); English dramatist and poet William Shakespeare (1564–1616), whose works many view as the culmination of Renaissance writing; Spain’s Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616), who penned Don Quixote (1605), the epic masterpiece that gave birth to the modern novel; and Frenchman François Rabelais (c. 1483–1553), who is best known for writing the five-volume novel Gargantua and Pantagruel.

What is the importance of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome?

St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome is the largest church in the world. Famous Renaissance architects Donato Bramante, Michelangelo, Carlo Maderno, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed the church itself as well as St. Peter’s Square in front of it. For many Catholics, it is one of the holiest places on Earth. Tradition holds that it was built on the burial site of St. Peter the Apostle.

The great artists of the Renaissance include the Italian painters/sculptors Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510), whose works include The Birth of Venus; Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), whose Mona Lisa and The Last Supper are among the most widely studied works of art; Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), whose sculpture David became the symbol of the new Florence; and Raphael Sanzio (1483–1520), whose School of Athens is considered by art historians to be the complete statement of the High Renaissance.

What do the words “cathedral” and “basilica” mean?

The word “cathedral” comes from the word “cathedra,” which means “throne” or “seat.” Every cathedral has a chair in the front for the bishop of the diocese. So, a cathedral is the bishop’s church. The word “basilica” is used for a specific style for a large church. Although St. Peter’s in Rome is the church of the pope, it is not a cathedral even though the pope is the bishop of Rome. The pope’s cathedral is a different church in Rome—St. John Lateran.

What is the importance of Renaissance art?

When many people hear the word “Renaissance,” they immediately think of the great painters like da Vinci and Raphael and great sculptors like Michelangelo. (These artists and their work will be explored in the chapter “Western Art, Photography, and Architecture.”)