PHILOSOPHY

What is philosophy?

Philosophy comes from the Greek words philo, meaning “love of,” and sophia, meaning “wisdom.” Thus, philosophy is literally a love of wisdom. In practice, it is the pursuit of understanding the human condition—how, why, and what it means to exist or to be. Philosophers use methods such as observation and questioning to discern the truth. Philosophy is traditionally divided between Eastern thought, originating mostly in India and China, and Western thought, coming mostly from Europe and North America.

Western thought consists of five branches: metaphysics (concerned with the nature of the universe or of reality); logic (the laws of reasoning); epistemology (the nature of knowledge and the process by which knowledge is gained); ethics (the moral values or rules that influence human conduct); and aesthetics (the nature of beauty or the criteria for art).

How old is philosophy?

Philosophy, apart from religion, emerged in the East and the West at about the same time—about 600 B.C.E. It was then that thinkers in Greece began questioning the nature of existence and scholars in China, particularly Confucius and Lao-Tzu, began teaching. Western philosophy is divided into three major periods: ancient philosophy (c. 600 B.C.E.–c. 400 C.E.); medieval philosophy (400s–1600s); and modern philosophy (since the 1600s). Chinese philosophy on how to live has had great influence over China and many surrounding Asian cultures up to the present. (It is covered in the “Asian History and Culture” chapter.)

Who was the first Greek philosopher?

Many claim that Thales of Miletus was the first major Greek philosopher. Born in 624 B.C.E., Thales was one of the “Seven Sages of Greece” (the others were Cleobulus, Solon, Chilon, Bias, Pittacus, and Periander). Thales discounted mythology and the Greek gods as the source of the universe; instead, he viewed water as the universal source of life and power. He believed that everything was composed of water. Although he was incorrect about water, he raised a question that is still investigated today: What is the one thing that makes up everything?

Like many other great philosophers, Thales was skilled in mathematics, using deductive reasoning to add to the world’s understanding of geometry. Some sources credit Thales with successfully predicting a solar eclipse. He also was active in politics.

Who was Solon?

Solon was a Greek politician, philosopher, and poet often credited with creating democratic foundations in the Greek city of Athens. He criticized political and moral decline and sought to improve his world and that of his fellow Athenians. He was a legal reformer and sought to reduce the harshness of criminal punishments instituted by a previous leader named Draco (for whom the word “draconian” is named). Solon also instituted many economic reforms and sought to help those trapped in debt. (Note that reducing the harshness of criminal punishments and helping those in debt are important issues in America today.) Solon is credited with favoring moderation as a way to live one’s life.

Who were the Sophists?

The Sophists were a group of Greek philosophers who were skilled in oratory (making speeches) and often charged fees to teach others rhetorical skills and increase their knowledge. According to their critics, they were more motivational speakers than deep thinkers. Leading Sophists included Protagoras, Gorgias, and Prodicus. Plato and Socrates disliked the Sophists, believing that they were not true philosophers. This may explain why the word “sophistry” today carries a negative connotation as the art of using weak arguments to mislead people.

Who are the “big three” ancient Greek philosophers?

Socrates (c. 470–399 B.C.E.), Plato (c. 428–347 B.C.E.), and Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) are considered the giants of ancient Greek philosophy.

Who was Socrates?

Although Socrates had many followers in his own time, his ideas and methods were controversial, which led him to be tried before judges and sentenced to death. He was charged with not worshipping the Athenian gods and for corrupting the young. Socrates was allowed to commit suicide by drinking the poison hemlock.

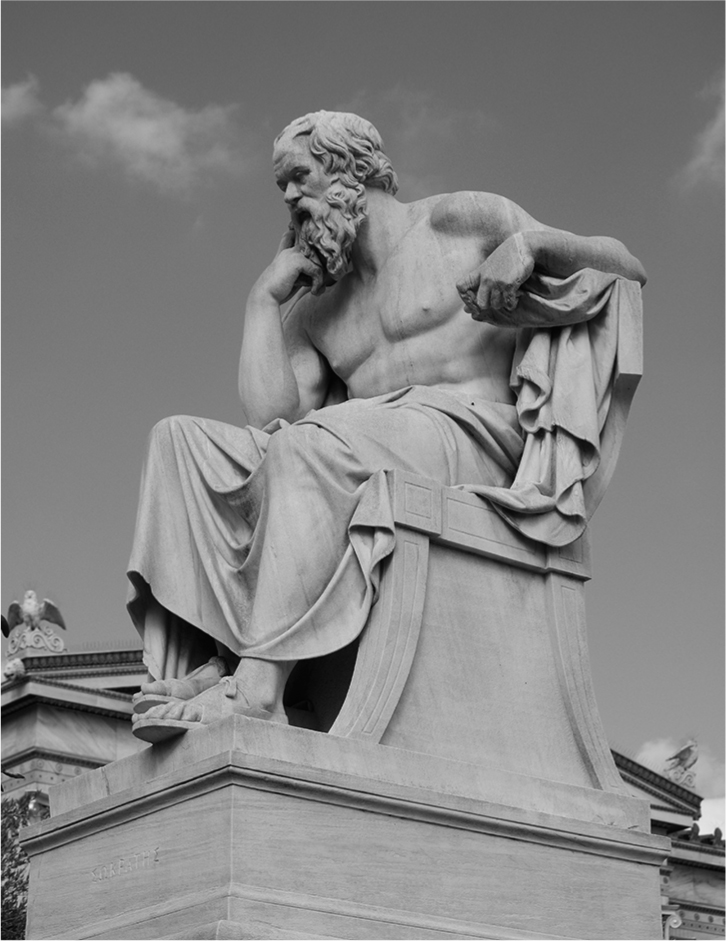

The Greek thinker Socrates was one of the primary founders of Western philosophy.

Except for his time in military service, Socrates lived his entire life in Athens, where he was as well known for his disheveled appearance as for his moral integrity, self-control, and quest for wisdom. He walked the streets of Athens, engaging people—including rulers who were supposed to be wiser than he—in conversation. In these conversations, he employed what came to be known as the “Socratic method” or dialectic, a series of seemingly simple questions designed to elicit a rational response.

Through the line of questioning, which usually centered around a moral concept, such as courage, the person being questioned was intended to realize that he did not truly know that which he thought he knew. Socrates’s theory was that once the person being questioned realized his weak understanding, he could divest himself of false notions and was then free to participate in the quest for knowledge.

These philosophical “disputes,” however, gained Socrates many enemies.

Though he left no writings, one of Socrates’s students, Plato, wrote down his recollections of the dialogues of Socrates. A staunch believer in self-examination and selfknowledge, Socrates is credited with saying that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” Socrates also believed that the psyche (or “inner self”) is what should give direction to one’s life—not appetite or passions.

What was Plato’s relationship to Socrates and Aristotle?

Plato was the disciple of Socrates and later the teacher of Aristotle. These three philosophers combined to lay the foundations of Western thought. Upset about the death of Socrates in 399, Plato left Athens and traveled throughout the Mediterranean. He returned to Athens in 387 B.C.E., and, one mile outside of the city, he established the Academy, a school of philosophy supported entirely by philanthropists; students paid no fees. One of the pupils there was a young Aristotle, who remained at the Academy for twenty years before venturing out on his own.

In what popular 1980s movie did Socrates appear?

In Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989), starring Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter, and George Carlin, the title characters travel back in time to find historical figures such as Napoleon Bonaparte and Abraham Lincoln to help rescue their high school history presentation. Bill and Ted also bring Socrates, whom they mistakenly refer to as “Sew-crates.” This is still an excellent movie that is fun to watch.

A detail of a fresco by the artist Raphael depicts the philosophers Plato and Aristotle, the next two generations to follow Socrates.

Plato wrote a series of dialogues in which Socrates does most of the talking. The most highly regarded of these is the Republic, in which Plato discusses justice and the ideal state. It was his belief that people would not be able to eliminate injustice from society until rulers became philosophers: “Until all philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy, and political greatness and wisdom meet in one, and those commoner natures who pursue either to the exclusion of the other are compelled to stand aside, cities will never have rest from their evils—no, nor the human race.” The problem for Plato was that kings and rulers were always promoting their selfinterest and the interests of specific groups who benefited, while the rest of the population suffered. Plato thought that philosophers as kings would pursue those things that were good in themselves and would thus benefit the state and the people.

Plato’s other works include Symposium, which considers ideal love; Phaedrus, which attacks the prevailing notions about rhetoric; Apology, which is a rendering of the speech Socrates delivered at his own trial in 399 B.C.E.; and Phaedo, which discusses the immortality of the soul and which is supposed to be a record of Socrates’s last conversation before he drank hemlock and died.

What is Plato’s theory of forms?

The theory of forms (also called the theory of ideas) is Greek philosopher Plato’s expression of his belief that there are forms that exist outside the material realm and therefore are unchanging—they do not come into existence, change, or pass out of existence. It is these ideas that, according to Plato, are the objects or essence of knowledge. So, for example, there is the idea or form of a tree that exists separate from all the actual trees.

Furthermore, he held that the body, the seat of appetite and passion which communes with the physical world, is inferior to the intellect that communes with the world of ideas. He believed the physical aspect of human beings to be irrational, while the intellect, or reason, was deemed to be rational.

Did Aristotle develop his own philosophy?

Yes, despite having studied under Plato for twenty years, Aristotle developed his own philosophy in a different direction. Aristotle rejected Plato’s theory of forms. While Aristotle, too, believed in material things and forms (the unchanging truths), unlike his teacher, he believed that it is the concrete things that have substantial being. Aristotle viewed the basic task of philosophy as explaining what things are and how they become what they are. It is for this reason that Aristotle had not only a profound and lasting influence on philosophy but also on science.

What does “epicurean” mean?

While “epicurean” has come to refer to anything relating to the pleasure of eating and drinking, it is an oversimplification of the beliefs of Greek philosopher Epicurus (341–270 B.C.E.), from whose name the word was derived. While Epicurus did believe that pleasure is the only good, and that it alone should be humankind’s pursuit, in actuality, Epicurus defined pleasure not as unbridled sensuality but as freedom from pain and as peace of mind, which can only be obtained through simple living.

In about 306 B.C.E., Epicurus established a school in Athens, which came to be known as the Garden School because residents provided for their own food by gardening. There, he and his students strived to lead lives of simplicity, prudence, justice, and honor. In this way, they achieved tranquility—the ultimate goal in life, according to the philosophy of Epicureanism. He further believed that intellectual pleasures are superior to sensual pleasures, which are fleeting. In fact, he held that one of the greatest and most enduring pleasures is friendship. Greek philosopher and writer Lucretius (c. 99–c. 55 B.C.E.) put forth these ideas in his poem “On the Nature of Things.” In more recent times, Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), author and signatory of the Declaration of Independence and third president of the United States, was a self-proclaimed Epicurean.

What was Stoicism?

Stoicism was a philosophy that believed in celebrating virtue, avoiding vice, enduring trials and tribulations, and acquiring wisdom. Founded by Zeno of Cyprus in the late third century B.C.E., Stoicism was a remarkably durable philosophy that had many adherents, including the great Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180 C.E.)

What famous painting shows Plato and Aristotle?

In 1511, the famous Italian Renaissance painter Raphael (1483–1520) completed The School of Athens, which depicts all the famous thinkers, scientists, and philosophers of ancient Greece. In the center stand Plato and Aristotle. Plato, with the orange tunic, points up to the world of forms and ideas. Aristotle, in the blue tunic, reaches out toward the physical world in front of him that can be seen, touched, and described.

Stoics valued not only wisdom but also bravery, justice, knowledge, and self-restraint. They sought to develop an askesis, a faculty that allows one to develop good judgment and an inner peace. They believed that happiness comes from acquiring wisdom and using sound reasoning to understand the workings of the world. Stoics often engaged in meditation and used the Socratic dialogue to test their beliefs and practices.

Stoics accepted that much of what happens to us in life is not in our control. However, one can control one’s reactions to life events. One cannot avoid the bad things that happen, but one can control one’s thinking and emotions so as not to suffer. Often, our thinking and feeling about what happens is the real source of our suffering.

MEDIEVAL PHILOSOPHY

What was the philosophy of the Middle Ages?

During the medieval period (800–1350), philosophers concerned themselves with applying the works of ancient Greek thinkers, such as Plato and then Aristotle, to Christian thought. This movement was called Scholasticism since its proponents were often associated with universities: the word “scholastic” is derived from the Greek scholastikos, meaning “to keep a school.” In the simplest terms, the goal of Scholasticism has been described as “the Christianization of Aristotle.” Medieval philosophers strived to use reason to better understand their religious faith. Scholasticism was both rational and religious.

Augustine of Hippo (aka St. Augustine) is regarded as one of the greatest philosophers of medieval Europe. Influenced by Plato and the Stoics, St. Augustine’s writings on topics like human will and ethics would impact later philosophers, such as Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Kierkegaard.

Why was Augustine important for medieval philosophy?

Christian medieval philosophers were greatly influenced by earlier writer Augustine (354–430), who lived in North Africa during a time when the last vestiges of the pagan world of the Romans were giving way to Christianity. His theological works, including sermons, books, and pastoral letters, reveal the influence of Plato. Augustine believed that understanding can lead one to faith and that faith can lead a person to understanding. His most important writing is called the Confessions.

How do you pronounce the name of Augustine?

Roman Catholics call him a saint and tend to put the accent on the first syllable of his name and pronounce the last syllable as “teen,” which is how most people pronounce the city named after him: St. Augustine, Florida. Protestants, however, tend to put the accent on the second syllable and pronounce the last syllable as “tin.” Many Protestants also drop the saint title.

Who was Anselm of Canterbury?

Anselm is often called the “Father of Scholasticism.” He wrote three important works: Monologion (the Monologue), Proslogion (the Discourse), and Cur Deus Homo (Why God Was a Man). He tackled two important questions: Can reason be used to prove the existence of God? Why was the Incarnation necessary? In other words, why did God have to become human in Jesus?

Anselm proposed an argument to prove the existence of God. It would later be called the “ontological argument.” God is that which nothing greater can be conceived. According to the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press, 1983): “If we were to suppose that God did not exist we should be involved in a contradiction since we could at once conceive of an entity greater than a non-existing God—an existing God.”

St. Thomas Aquinas is most renowned for his seminal work the Summa theologiae, a comprehensive overview of Catholic theological teachings originally intended for students.

According to Anselm, God is the greatest thing we can imagine. Then, he assumes it is better to exist than to not exist. Thus, if one says that God, the greatest thing one can imagine, does not exist, someone could respond that that is not the greatest thing a person could imagine. The greatest thing one could imagine is a god who does exist.

Some people get Anselm’s argument; some people do not. His idea is that for God to be the greatest thing, God would have to exist. Some criticize Anselm’s argument as being just a play on words.

Who was Thomas Aquinas?

Thomas Aquinas (1224–1274) was one of the most influential Christian theologians of the Middle Ages. The most important writing of Thomas Aquinas was his Summa Theologiae, a comprehensive overview of all the Christian theological topics of the time. Aquinas is particularly important for integrating the thought of Greek philosopher Aristotle with Christian thought. In the 1500s, during the Protestant Reformation in Europe, many Protestant writers rejected the teachings of Aquinas.

Who were the great Islamic philosophers of the Middle Ages?

At the same time that the Christian scholastic philosophers lived and wrote, several important Islamic philosophers were also making important contributions to philosophy. During the Middle Ages, three thinkers of the Islamic world stood out as important interpreters of Greek thought and, therefore, as a bridge between ancient philosophy and the Scholasticism of the Middle Ages: their Latin names are Avennasar, Averroës, and Avicenna.

Avennasar (c. 878–950), who studied with Christian Aristotelians in Baghdad (Iraq), proved so adept at applying the teachings of Aristotle to Muslim thought that he became known as “the second Aristotle” or “the second teacher.” He posited that philosophy and religion are not in conflict with each other; rather, they parallel one another.

Known for his work in interpreting the great Aristotle for the Muslim world, Avicenna (980–1037) is sometimes referred to as “the third teacher.” He was also the first to expand the distinction between essence and existence.

Averroës (1126–1198) also was no stranger to Aristotle, writing commentaries on him as well as on Plato. Averroes also wrote on religious law and philosophy as well as religion and logic.

Some people are surprised to learn about these Muslim philosophers. However, in the Middle Ages, the Muslim world was ahead of Europe in translating Greek philosophers and in the study of medicine, navigation, mathematics, and science. Notice that the word “algebra” is an Arabic word and that our numbers 1, 2, 3, etc., are called “Arabic numerals.”

Who was Maimonides?

Moses ben Maimon, known as Maimonides (c. 1135–1204), was a Jewish philosopher, scholar, and writer on the Torah (Jewish Law). Born in Cordoba in what today is Spain, he lived in Morocco and Egypt. He wrote a significant work on philosophy called The Guide for the Perplexed.

Which philosopher of the Renaissance period contributed much to philosophy and political science?

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), a native of Florence, Italy, was a master of political philosophy who had an indelible impact on many Western political leaders. In his most famous work, The Prince, Machiavelli described how rulers must use any means necessary to attain and keep power. There is much of an “ends justifies the means” rationalization in Machiavelli’s political philosophy.

Machiavelli was not trying to describe how things should work or how we want them to work in the political realm. Rather, he was trying to tell how things actually work in the real world. He was trying to be honest about political power. This honesty and candidness is what people love and hate about Machiavelli.

For example, he thought a ruler should only tell the truth when it benefited the ruler, but the ruler should lie when necessary. He also believed that although a ruler should act like he is religious and moral, the ruler should always be ready to act immorally if that was what was needed to further his power.

Machiavelli thought that it was better for a ruler to be feared by his subjects than to be loved by them. If they feared the ruler, the ruler was in control. If the ruler was dependent on the love of the subjects, then he was dependent on them, and they could stop loving the ruler at any time.

Who was Sir Thomas More?

Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) was an English politician, lawyer, and philosopher best known for his relationship with King Henry VIII and for writing Utopia. More served as an adviser to the king and served as chancellor. He opposed Henry VIII’s separation from the Catholic Church and the king’s elevation of himself as the head of the Church of England. For his political heresy, More was executed by beheading. For this reason, many view More as a martyr.

In Utopia, More described an ideal state in which the needs of the people were placed above the needs of the privileged few. Many see the work as an attempt by More to criticize aspects of British life in his time.

What is the “doctrine of idols”?

This was a phrase used by English philosopher Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) in his written attack on the widespread acceptance of the traditional concepts used in philosophy, theology, and explanations of the natural world. In his 1620 work, Novum Organum, Bacon vehemently argues that human progress is held back by adherence to certain concepts, which we do not question. By hanging on to these concepts, or “idols,” we may proceed in error in our thinking. In holding to notions accepted as true, we run the danger of dismissing any new notion, a tendency Bacon characterized as arrogance. To combat these obstacles, Bacon advocated a method of persistent inquiry. He believed that humans could understand nature only by carefully observing it with the help of instruments. He went on to describe scientific experimentation as an organized endeavor that should involve many scientists and that requires the support of leaders. Thus, Bacon is credited with no less than formulating modern scientific thought.

Why is René Descartes considered the “Father of Modern Philosophy”?

French mathematician and philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) was living in Holland in 1637 when he published his first major work, Discourse on Method. In this treatise, he extends mathematical methods to science and philosophy, asserting that all knowledge is the product of clear reasoning based on self-evident premises. This idea, that there are certitudes, provided the foundation for modern philosophy, which dates from the 1600s to the present.

Considered one of the founders of modern philosophy, French mathematician and scientist René Descartes is often remembered for his famous quote “I think, therefore I am.”

Descartes may best be known for the familiar phrase “I think, therefore I am” (Cogito ergo sum in Latin). This assertion is based on his theory that only one thing cannot be doubted, and that is doubt itself. The next logical conclusion is that the doubter (thinker) must, therefore, exist. In other words, “If I am doubting, I must be thinking. If I am thinking, I must exist to do the thinking.”

The correlation to the concept (“I think, therefore I am”) is dualism, the doctrine that reality consists of mind and matter. Since the thinker thinks and is, he or she is both mind (idealism) and body (matter, or material). Descartes concluded that mind and body are independent of each other, and he formulated theories about how they work together.

Descartes’s other major works include Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), which is his most famous, and Principles of Philosophy (1644). His philosophy became known as Cartesianism (from Cartesius, the Latin form of his name).

Who was Thomas Hobbes?

Hobbes (1588–1679) was a seminally important English political philosopher who wrote about social contract theory, the sinfulness of the human condition, and the brutality of modern life. He is known for explaining that man in a state of nature will lead to destruction and anarchy. Therefore, man must set up the state to establish order and protect man from himself.

Hobbes explained much of his political philosophy in his work The Leviathan, which was influenced by the chaos of the English Civil War (1642–1651). He argues that man’s sinful and anarchic nature can be overcome only with a strong, central government. One of the most oft-cited passages from the book is his pessimistic take on human life without such a government: “the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

What was the Enlightenment?

The Enlightenment, which is also referred to as the Age of Reason, was a period when European philosophers emphasized the use of reason as the best method for learning the truth. The term “enlightenment” comes from the idea of seeing something clearly in the light. Here, it refers to seeing truth and reaching understanding through reason.

Beginning in the 1600s and lasting through the 1700s, philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), Voltaire (1694–1778), and John Locke (1632–1704) explored issues in education, law, and politics. They published their thoughts, issuing attacks on social injustice, religious superstition, and ignorance. Their ideas fanned the fires of the American and French revolutions in the late 1700s.

Hallmarks of the Age of Reason include the idea of the universal truth (two plus two always equals four, for example); the belief that nature is vast and complex but well ordered; the belief that humankind possesses the ability to understand the universe; the philosophy of Deism, which holds that God created the world and then left it alone; and the concept of the rational will, which posits that humans make their own choices and plans and, therefore, do not have a fate thrust upon them. The philosophies put forth during the Age of Reason were critical to the development of Western thought.

René Descartes (1596–1650), who refused to believe anything unless it could be proved, perhaps best expressed the celebration of individual reason during this era. His statement “I think, therefore I am” sums up the feelings of skeptical and rational inquiry that characterized intellectual thought during this era.

English physician and philosopher John Locke is considered the founder of Liberalism, the political philosophy concerned with civil liberties that heavily impacted the beliefs of Thomas Jefferson and other Americans.

Which Enlightenment thinker particularly influenced Thomas Jefferson?

John Locke’s writings greatly influenced several of the Founding Fathers, most notably Thomas Jefferson. Locke wrote Essay Concerning Human Understanding and Two Treatises of Government. His explanation of natural law and the social contract are key progenitors of Jefferson’s ideas, reflected in the Declaration of Independence. Locke believed that the government should protect the rights of the people. Jefferson identified this in the Declaration of Independence by declaring that people have certain “inalienable rights,” including “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Are the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution the same?

The two terms describe interrelated and sequential European intellectual movements that took place from the 1500s to the 1800s. Together, the movements shaped an era that would lay the foundations of modern western civilization, foundations that required the use of reason, or rational thought, to understand the universe, nature, and human relations. During this period, many of the greatest minds in Europe developed new scientific, mathematical, philosophical, and social theories.

Scientists came to believe that observation and experimentation would allow them to discover the laws of nature. Thus, the scientific method emerged, which required tools. Soon, the microscope, thermometer, sextant, slide rule, and other instruments were invented. Scientists working during this time included Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727), Joseph Priestley (1733–1804), and René Descartes (1596–1650). The era witnessed key discoveries and saw rapid advances in astronomy, anatomy, mathematics, and physics. The advances had an impact on education. Universities introduced science courses to the curricula, and elementary and secondary schools followed suit. As people became trained in science, new technologies emerged; complicated farm machinery and new equipment for textile manufacturing and transportation were developed, paving the way for the Industrial Revolution.

What is empiricism?

Empiricism is the philosophical concept that experience, which is based on observation and experimentation, is the source of knowledge. According to empiricism, the information that a person gathers with his or her senses is the information that should be used to make decisions without regard to reason or to either religious or political authority. The philosophy gained credibility with the rise of experimental science in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and it continues to be the outlook of many scientists today.

There are three key figures who developed this philosophical approach:

• English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) asserted that there are no such things as innate ideas: the mind is born blank, and all knowledge is derived from human experience.

• Irish clergyman George Berkeley (1685–1753) believed that nothing exists except through the perception of the individual and that it is the mind of God that makes possible the apparent existence of material objects.

• Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–1776) took the doctrine of empiricism to the next level: skepticism. We can never know anything for sure. Human knowledge is restricted to the experience of ideas and impressions and therefore cannot be verified as true.

Who was Montesquieu?

Charles-Louis, Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755) was a French political philosopher credited with advocating a strong belief in the separation of powers between different branches of the government. His philosophy directly influenced many of the Founding Fathers of the fledging United States of America—a country that adopted Montesquieu’s philosophy of separation of powers into the U.S. Constitution.

He was well known for his beliefs in legal relativism, that what is good for one may not be good for another. He believed that rulers often must adapt to changing conditions in society and be flexible in their response.

Who was Jean-Jacques Rousseau?

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) was another famous French philosopher, best known for his work The Social Contract. Unlike Thomas Hobbes, Rousseau believed in the inherent goodness of man and warned that it was the government that often served as the evil in the world. He lived at a time of authoritarian kings who denied the rights of common people. Rousseau believed that men were born equal and were entitled to freedom and the opportunity for individual self-fulfillment. He wrote: “Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.” He also advocated for a better system of education and warned against authoritarian governments. He is perhaps best known for his writings on equality.

Who is Immanuel Kant? Why is he relevant today?

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) remains one of the great modern thinkers because he developed a whole new philosophy, one that completely reinterpreted human knowledge. A professor at Germany’s Königsberg University, Kant lectured widely and was a prolific writer. His most important work came somewhat late in life—after 1775. It was in that year that he undertook “a project of critical philosophy,” in which he aimed to answer the three questions that, in his opinion, have occupied every philosopher in Western history: What can I know? What ought I do? For what may I hope?

Kant’s answer to the first question (What can I know?) was based on one important conclusion: What a person can know or make claims about is only his or her experience of things, not the things in themselves. The philosopher arrived at this conclusion by observing the certainty of math and science, and he determined that the fundamental nature of human reality (metaphysics) does not rely on or yield the genuine knowledge of science and math. For example, Newton’s law of inertia—a body at rest tends to remain at rest, and a body in motion tends to remain in motion—does not change based on human experience. The law of inertia is universally recognized as correct and, as such, is a “pure” truth, which can be relied on. But human reality, argued Kant, does not rest on any such certainties. That which a person has not experienced with his or her senses cannot be known absolutely. Kant therefore reasoned that free will cannot be proved or disproved—nor can the existence of God.

Even though what humans can know is extremely limited, Kant did not become skeptical. On the contrary, he asserted that “unknowable things” require a leap of faith. He further concluded that since no one can disprove the existence of God, objections to religion carry no weight. In this way, Kant answered the third question posed by philosophers: For what may I hope?

German philosopher Immanuel Kant was the founder of transcendental idealism, the idea that we do not recognize the outside world as it really is but only as it appears to us through our sensibilities.

After arriving at the conclusion that each person experiences the world according to his or her own internal laws, Kant began writing on the problem of ethics, answering the second question (What ought I do?). In 1788, he published the Critique of Practical Reason, asserting that there is a moral law, which he called the “categorical imperative.” Kant argued that a person could test the morality of his or her action by asking if the person was willing for his or her action to become a universal rule applicable to all people: “Act as if the maxim (rule) from which you act were to become through your will a universal law.”

For example, is a thief acting morally? A thief might justify his or her stealing, but typically, he or she is not willing to make stealing a universal rule such that someone could steal from him or her. Therefore, he or she is not acting morally when he or she steals. Honest people act morally because they are willing to let the rule “speak honestly” and become a universal moral law. Kant concluded that when a person’s actions conformed to this “categorical imperative,” then he or she was doing his or her duty, which would result in goodwill.

Kant’s theories have remained relevant to philosophy for more than two centuries. Modern thinkers have either furthered the school of thought that Kant initiated, or they have rejected it. Either way, the philosopher’s influence is still felt. It’s interesting to note that among his writings is an essay on political theory (Perpetual Peace), which first appeared in 1795. In it, Kant described a federation that would work to prevent international conflict; the League of Nations and the United Nations, created more than a century after Kant, are the embodiments of this idea.

What is the Hegelian dialectic?

It is the system of reasoning put forth by German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770–1831), Kant’s most well-known protégé, who theorized that at the center of the universe, there is an absolute spirit that guides all reality. According to Hegel, all historical developments follow three basic laws. First, each event follows a necessary course (in other words, it could not have happened in any other way); each historical event represents not only change but progress. Second, each historical event, or phase, tends to be replaced by its opposite. And third, this opposite is later replaced by a resolution of the two extremes.

This third law of Hegel’s dialectic is the “pendulum theory” discussed by scholars and students of history. It says that events swing from one extreme to the other before the pendulum comes to rest in the middle. The extreme phases are called the thesis and the antithesis; the resolution is called the synthesis. Based on this system, Hegel asserted that human beings can comprehend the unfolding of history.

The next important movement is existentialism. Why is it called existentialism?

Existentialism starts by thinking about human existence. This contrasts with thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, who began by proving the existence of God and then drawing conclusions about how to live based on a belief in God. Existentialists, by starting with human existence, note that the meaning and purpose of life are not obvious. In fact, life often seems meaningless and even cruel.

Existentialists then point out that rational thought cannot prove the existence of God. We cannot know for certain that God exists. At this point, different types of existentialism emerge. Some existentialists move toward atheism, which claims there is no God. Others go to the opposite position that although the existence of God cannot be proven, there can be faith in the existence of God. Faith is essential since proof of God is impossible. Thus, there are several kinds of existentialists.

Some, like Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) and Albert Camus (1913–1960), were atheists. Others, such as Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), were believers. Kierkegaard rejected the principles put forth by traditional philosophers such as Georg Hegel, who had considered philosophy as a science, asserting that it is both objective and certain. Kierkegaard overturned this assertion, citing that truth is not objective but rather subjective; that there is no such thing as universal truths; and that human existence is not understandable in scientific terms. He maintained that human beings must make their own choices based on their own knowledge.

Existentialists grappled with the dilemma that human beings must use their free will to make decisions—and assume responsibility for those decisions—without knowing conclusively what is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad. In other words, there is no way of knowing absolutely what the correct choices are, and yet, individuals must make choices all the time and be held accountable for them. Sartre described this as a “terrifying freedom.”

However, theologians such as American Paul Tillich (1886–1965) reconsidered the human condition in light of Christianity, arriving at far less pessimistic conclusions than did Sartre. For example, Tillich asserted that “divine answers” exist. Similarly, Jewish philosopher Martin Buber (1878–1965), who was also influenced by Kierkegaard, proposed that a personal and direct dialogue between the individual and God yields truths.

Who was Friedrich Nietzsche? What was his concept of the “will to power”?

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) developed many theories of human behavior, and the will to power was one of these. While other philosophers (including the ancient Greek Epicurus) argued that humans are motivated by a desire to experience pleasure, Nietzsche asserted that it was neither pleasure nor the avoidance of pain that inspires humankind but rather the desire for strength and power. He argued that in order to gain power, humans would even be willing to embrace pain.

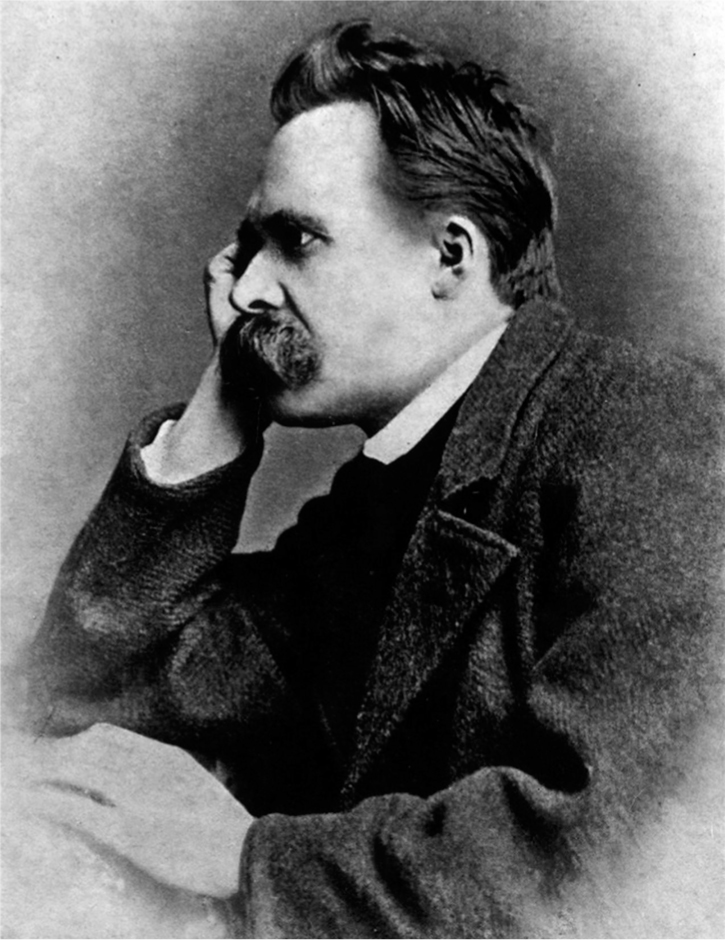

Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the superman is a person who asserts power over themselves without regard to social mores, a concept corrupted by the Nazis to justify their actions against Jews and other minorities.

However, it’s critical to note that he did not view this will to power strictly as a will to dominate others: Nietzsche glorified a superman or “overman” (übermensch), an individual who could assert power over himself (or herself). He viewed artists as one example of an overman—since that person successfully harnesses his or her instincts through creativity and, in so doing, has actually achieved a higher form of power than would the person who only wishes to dominate others.

Who was Jeremy Bentham?

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) was an English philosopher associated with utilitarianism and the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain. He disagreed with the concept of natural law.

Utilitarianism represents the core belief that the best course of action is the one that produces the most overall happiness. He believed that politicians and public policy in general should serve the interests of the common good and the greatest number of people. He believed in the “greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number.”

Bentham was also an important legal reformer who advocated for the separation of church and state, abolition of the death penalty, and equal rights for women.

Who was John Stuart Mill?

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) was an English philosopher associated with the philosophy of utilitarianism. In fact, in his book Utilitarianism, Mill articulated the “greatest happiness principle”—that people should act to produce the greatest total happiness in society, within reason. Mill distinguished between higher and lower forms of happiness. The writings of Bentham and Mill helped to promote the idea that governments should work for what is best for most people and not just promote the interests of the wealthy and powerful.

Mill may be best known for his work On Liberty (1841), which is often seen as a progenitor of modern American thought regarding individual liberty and freedom of speech. Mill believed that the government should not censor speech, even false speech, but should allow it to collide with truth and show its errors to society.

What happened to Jeremy Bentham’s body?

Bentham wanted to support the development of medical science, which required the use of human cadavers (dead bodies) so doctors could learn through dissection. At that time, there was no system for providing such human bodies. Unfortunately, a black market developed for bodies that were sometimes stolen from graves, or people, such as the homeless, would be murdered so that their bodies could be sold. (The story in Mark Twain’s famous book Tom Sawyer is built around such a grave robbery.) Bentham encouraged people to donate their bodies, and he set an example by donating his. After his body was used for science, it was stuffed and preserved and put in a glass case. (Do an online image search for “Jeremy Bentham body.”)

Who was Bertrand Russell?

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) was an English philosopher and Nobel laureate who was arguably the most influential philosopher of the twentieth century. In his early works, he focused more on mathematics, like many of the early Greek philosophers.

He wrote The Problems of Philosophy, where he attacked idealism and advanced a theory of empiricism and realism. He advocated a system that he called “logical analysis,” where concepts are examined at their roots or atoms to understand their merit and place in the world. He was well known for his politics and his pacifism—including an arrest at a nuclear power plant at the age of eighty-nine. Russell lived to the ripe old age of ninety-eight, making him perhaps the oldest of all famous philosophers.

PHILOSOPHY AND GOVERNMENT

What is natural law?

Natural law is the theory that some laws are fundamental to human nature, and, as such, they can only be known through human reason—without reference to man-made law. Roman orator and philosopher Cicero (106–43 B.C.E.) insisted that natural law is universal, meaning it is binding to governments and people everywhere.

What is the social contract?

The social contract is the concept that human beings have made a deal with their government, and within the context of that agreement, both the government and the people have distinct roles. The theory is based on the idea that humans abandoned a natural free and ungoverned condition in favor of a society that provides them with order, structure, and, very importantly, protection.

Through the ages, many philosophers have considered the role of both the government and its citizens within the context of the social contract. In the theories of English philosophers John Locke (1632–1704) and his predecessor, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), the social contract was inextricably tied to natural law (the theory that some laws are fundamental to human nature). Locke argued that people first lived in a state of nature, where they had no restrictions on their freedom. Realizing that conflict arose as each individual defended his or her own rights, the people agreed to live under a common government, which offered them protection. But in doing so, they had not abandoned their natural rights.

On the contrary, argued Locke, the government should protect the rights of the people—particularly the rights of life, liberty, and property. Locke put these ideas into print, publishing his two most influential works in 1690: Essay Concerning Human Understanding and Two Treatises of Government. These works firmly established him as the leading “philosopher of freedom.”

Why are Thomas Paine’s philosophies important to democratic thought?

English political philosopher and author Thomas Paine (1737–1809) believed that a democracy is the only form of government that can guarantee natural rights. Paine arrived in the American colonies in 1774. Two years later, he wrote Common Sense, a pamphlet that galvanized public support for the American Revolution (1775–1783), which was already underway.

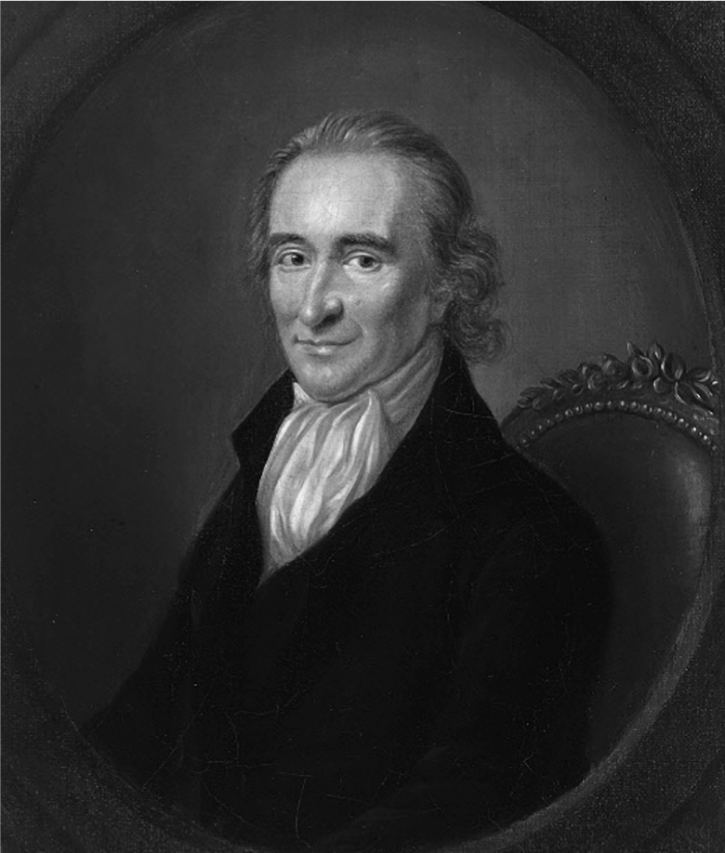

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense encouraged support for the American Revolution.

During the struggle for independence, Paine wrote and distributed a series of sixteen papers called Crisis, upholding the rebels’ cause in their fight. Paine penned his words in the language of common speech, which helped his message reach a mass audience in America and elsewhere. He soon became known as an advocate of individual freedom.

In 1791 and 1792, Paine, now back in England, released The Rights of Man, a work in which he defended the cause of the French Revolution (1789–1799) and appealed to the British people to overthrow their monarchy. For this, he was tried and convicted of treason in his homeland. Escaping to Paris, the philosopher became a member of the revolutionary National Convention. But during the Reign of Terror (1793–1794) of revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794), Paine was imprisoned for being English.

An American minister interceded on Paine’s behalf, insisting that Paine was actually an American. Paine was released on this technicality. He remained in Paris until 1802 and then returned to the United States. Though he played an important role in the American Revolution by boosting the morale of the colonists, he nevertheless lived his final years as an outcast and in poverty. Part of his unpopularity in his later years was that he opposed slavery when many supported it, and he was very critical of organized religion.

Who was Michel Foucault?

French postmodernist philosopher Michel Foucault (1926–1984) had little use for Marxism as a political philosophy that explained the history of the world. Foucault devoted much of his career to being a philosophical relativist, showing that truth has changed quite mightily through the ages.

Foucault also wrote about penal systems, the failures of psychology, and sexuality. He attacked many attempts at curing the mentally ill and rehabilitating the prisoner, as he felt that prisons were inhumane institutions. Early in his life, his sexuality caused him distress and led to several suicide attempts. Foucault died of AIDS in 1984.

What is Marxism?

Marxism is an economic and political theory named for its originator, Karl Marx (1818–1883). Marx was a German social philosopher and revolutionary who met another German philosopher, Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), in Paris in 1844, beginning a long collaboration. Four years later, they wrote The Communist Manifesto, laying the foundation for socialism and communism. The cornerstone of Marxism, to which Engels greatly contributed, is the belief that history is determined by economics.

Based on this premise, Marx asserted that economic crises will result in increased poverty, which, in turn, will inspire the working class (proletariat) to revolt, ousting the capitalists (bourgeoisie). According to Marx, once the working class has seized control, it will institute a system of economic cooperation and a classless society. In his most influential work, Das Kapital (Capital: A Critique of Political Economy), an exhaustive analysis of capitalism published in three volumes (1867, 1885, and 1894), Marx predicted the failure of the capitalist system based on his belief that the history of society is “the history of class struggle.” He and Engels viewed an international revolution as inevitable.