POLITICAL AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

NATIONALISM

How old is nationalism?

Nationalism, a people’s sense that they belong together as a nation because of a shared history and culture and, often, because of a common language and/or religion, emerged at the close of the Middle Ages. By the 1700s, several countries, notably England, France, and Spain, had developed as “nation-states,” groups of people with a shared background who occupy a land that is governed independently.

By the 1800s, nationalism had become a powerful force, and the view took hold that any national group has the right to form its own state. However, in many places, nationalist identities did not match political boundaries. For example, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe, several different nationalities existed within its political boundaries. In the United States, nationalism took the form of manifest destiny, the mission to expand the country’s boundaries to include as much of North America as possible.

In the 1800s, nationalist literature began to be written. Also, many composers started writing nationalist music, such as Frédéric Chopin (Polish), Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov (Russian), Richard Wagner (German), Antonín Dvorák (Czech), and, in the twentieth century, Aaron Copland (American).

Because of the belief called national self-determination, some nations achieved independence. Greece gained freedom from Turkey in 1829, and Belgium became independent from the Netherlands in 1830. Others formed new and larger countries by the unification of numerous smaller states, such as Italy in 1870 and Germany in 1871. The trend continued into the twentieth century with many examples, such as the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire following World War I that resulted in the formation of the independent countries of Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and, later, Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia was later broken up into Slovenia, Macedonia, Croatia, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro.

While nationalism is a source of pride and patriotism and has had many positive results, some leaders (notably German dictator Adolf Hitler) have carried it to extremes, initiating large-scale movements that resulted in the persecution of other peoples and in the hideous practice of ethnic cleansing.

What is one of the big problems with nationalism?

Political situations become complicated when national identities of a people do not match the political boundaries in which they live. This has been a long-term problem and still exists today in many places. For example, in the country of Spain, the people in the region of Catalonia, which includes the city of Barcelona, speak the language of Catalan. Many see their national identity as Catalan and not Spanish even though they are currently part of Spain. Some want an independent country. In northern Spain is the Basque region that extends into France. Some Basques want an independent country.

THE SOLIDARITY MOVEMENT IN POLAND

What is Solidarity?

It was a worker-led movement for political reform in Poland during the 1980s that contributed greatly to the downfall of communism. The movement was inspired by Pope John Paul II’s June 1979 visit to his native Poland, where, in Warsaw, he delivered a speech to millions, calling for a free Poland and a new kind of “solidarity.” (As scholar and author Timothy Garton Ash noted, “Without the Pope, no Solidarity. Without Solidarity, no Gorbachev. Without Gorbachev, no fall of Communism.”)

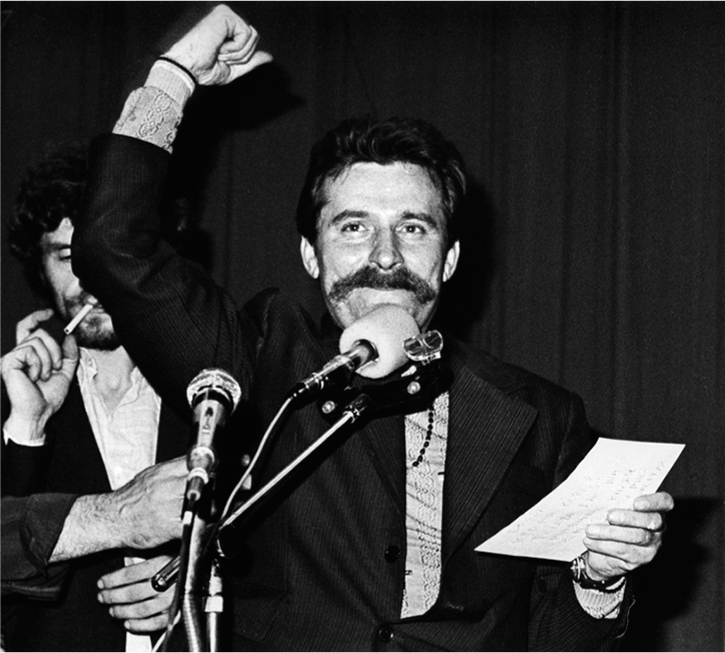

Lech Wałesa (pictured during a 1980 shipyard strike) led a workers’ movement in Poland called Solidarity that overthrew the communist government. He served as president of Poland from 1990 to 1995.

Shipyard electrician Lech Wałesa (1943–) became the leader of Solidarity, formed in 1980 when fifty labor unions banded together to protest Poland’s communist government. The unions staged strikes and demonstrations. By 1981, Solidarity had gained so many followers that it threatened Poland’s government, which responded (with the support of the Soviet Union) by instituting martial law in December of that year. The military cracked down on the activities of the unions, abolishing Solidarity in 1982 and arresting its leaders, including the charismatic Wałesa.

But the powerful people’s movement, which had also swept up farmers (who formed the Rural Solidarity), could not be suppressed. Martial law was lifted in mid-1983, but the government continued to exert control over the people’s freedom. That year, Wałesa received the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to gain workers’ rights and prevent violence. Solidarity continued its work for reform.

In 1989, with the collapse of communism on the horizon (people’s movements in Eastern Europe had combined with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost to herald the system’s demise), the Polish government reopened negotiations with Solidarity leadership. Free elections were held that year, with the labor party candidates gaining numerous seats in Parliament. In 1990, Wałesa was elected president, at which time he resigned as chairman of Solidarity. Poland’s Communist Party was dissolved that year.

In the years following, Poland moved toward becoming a democracy with democratic institutions. However, in 2015, Andrzej Duda (1972–) became president as the candidate of the right-wing Law and Justice Party. Many critics see him as an authoritarian who is moving Poland away from democracy. In particular, he has totally undermined the independence of the judiciary.

APARTHEID IN SOUTH AFRICA

How were the Boer Wars important for the origins of South Africa?

The Boer Wars were conflicts between the British and the Afrikaners (or Boers, who were Dutch descendants living in South Africa) at the end of the nineteenth century in what is today South Africa. The first war, a Boer rebellion, broke out in 1880 when the British and the Afrikaners fought over the Kimberley area (Griqualand West), where a diamond field had been discovered. The fighting lasted a year, at which time the South African Republic (established in 1856) was restored.

But the stability would not last long: In 1886, gold was discovered in the Transvaal, and though the Afrikaner region was too strong for the British to attempt to annex it, they blocked the Afrikaners’ access to the sea. In 1899, the Afrikaner republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal joined forces in a war against Britain. The fighting raged until 1902, when the Afrikaners (the Boers) surrendered. Part of the British strategy had been to round up Afrikaner women and children and put them in concentration camps. Over 27,000 died in the camps.

For a time after the Boer War (also called the South African War), the Transvaal became a British crown colony. In 1910, the British government combined its holdings in southern Africa into the Union of South Africa. In 1948, the system of apartheid was created, leading to an unequal society with whites at the top and blacks at the bottom.

In 1961, the land became the Republic of South Africa.

What was apartheid? What was the antiapartheid movement?

Apartheid was a system of strict racial segregation in the country of South Africa. (The word “apartheid” means “separateness” in the South African language of Afrikaans.) Under apartheid, which the Afrikaner Nationalist Party formalized in 1948, minority whites were given supremacy over nonwhites. The system further separated nonwhite groups from each other so that mulattoes (those of mixed race), Asians (mostly Indians), and native Africans were segregated. The policy was so rigid that it even separated native Bantu groups from each other.

Blacks were not allowed to vote even though they were and are the majority population. Apartheid was destructive to society and drew protests at home and abroad. But the South African government adhered to the system, claiming it was the only way to keep peace among the country’s various ethnic groups.

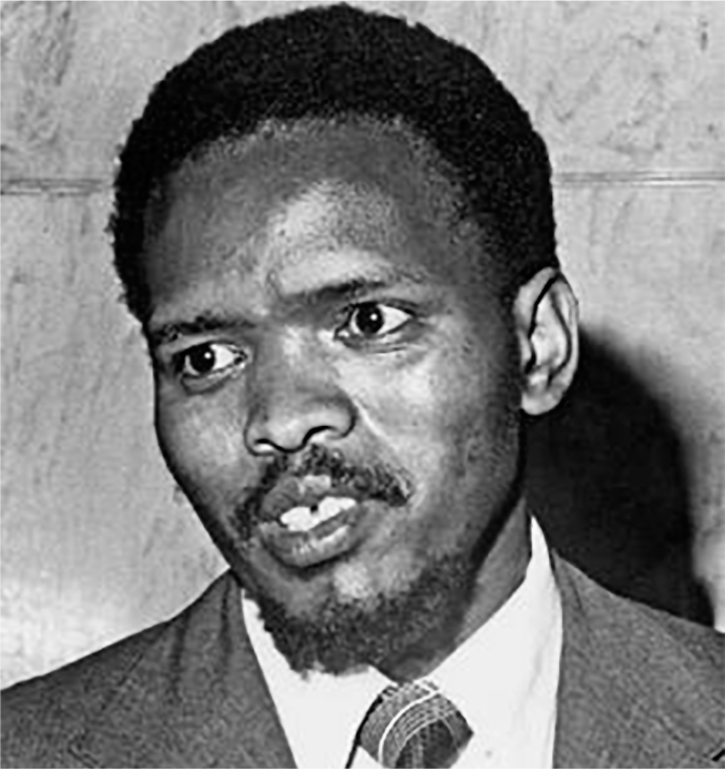

Who was Stephen Biko?

Stephen Biko (1946–1977) was a black leader in the fight against South African apartheid and white minority rule. In 1969, Biko, who was then a medical student, founded the South African Students’ Organization, which took an active role in the black consciousness movement, a powerful force in the fight against apartheid. Preaching a doctrine of black self-reliance and self-respect, Biko organized protests, including antigovernment strikes and marches. Viewing such activities as a challenge to its authority and fearing an escalation of unrest, in August 1977, the white government had Biko arrested.

Stephen Biko founded the South African Students’ Organization, which actively fought against the injustices of apartheid.

Within one month, he died in prison. Evidence indicated he had died at the hands of his jailers, a revelation that only cemented antigovernment sentiment. Along with Nelson Mandela (1918–2013), who was imprisoned in South Africa from 1962 to 1990 for his political activities, Biko became a symbol of the antiapartheid movement, galvanizing support for racial justice at home and abroad.

What was the Soweto Uprising?

The Soweto Uprising referred to a protest by South African black school-aged youths that began on June 16, 1976. The youths protested the introduction of Afrikaans, a Dutch language, into their schools. They associated Afrikaans with the government’s support of apartheid. More than 20,000 students participated in the protest, which resulted in more than 170 deaths.

June 16 is now a public holiday, called Youth Day, in South Africa.

South African president F. W. de Klerk shakes hands with Nelson Mandela at the 1992 World Economic forum. Two years later, blacks were eligible to vote, and de Klerk was replaced by Mandela.

How did apartheid end?

Protesters against apartheid staged demonstrations and strikes, which sometimes became violent. South Africa grew increasingly isolated as countries opposing the system refused to trade with the apartheid government. The no-trade policy had been urged by South African civil rights leader and Anglican bishop Desmond Tutu (1931–), who led a nonviolent campaign to end apartheid and in 1984 won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. During the 1980s, the economic boycott put pressure on the white-minority South African government to repeal apartheid laws. It finally did so, and in 1991 the system of segregation was officially abolished.

White South African leader F. W. de Klerk (1936–), who was elected in 1989, had been instrumental in ending the apartheid system. In April 1994, South Africa held the first elections in which blacks were eligible to vote. Not surprisingly, black South Africans won control of Parliament, which in turn elected black leader Nelson Mandela as president, and de Klerk was retained as deputy president. The two men won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 for their efforts to end apartheid and give all of South Africa’s peoples full participation in government. In 1996, the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a panel headed by Desmond Tutu and charged with investigating the political crimes committed under apartheid, began work. Its investigations continued into 1999, with many findings proving controversial.

U.S. POPULISM, PROGRESSIVISM, AND THE LABOR MOVEMENT

What was populism in the late 1800s and early 1900s?

Populism was a commoners’ movement that was formalized in the United States in 1891 with the founding of the Populist Party, which worked to improve conditions for farmers and laborers. In the presidential election of 1892, the party supported its own political candidate, James B. Weaver (1833–1912). Though Weaver lost, the Populists remained a strong force. In the presidential election four years later, they backed Democratic Party candidate William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925), a self-proclaimed commoner who was sympathetic to the causes of the Farmers’ Alliances, and the National Grange movement as well as the nation’s workers. (The National Grange movement promoted the economic and political interests of farmers. It still exists; its website is nationalgrange.org.)

Bryan lost to William McKinley (1843–1901), and soon after the election, the Populist Party began to fall apart, disappearing altogether by 1908. Nevertheless, the party’s initiatives continued to figure into the nation’s political life for the next two decades, and many populist ideas were made into laws, including the free coinage of silver and government issue of more paper money (“greenbacks”) to loosen the money supply, adoption of a graduated income tax, passage of an amendment allowing for the popular election of U.S. senators (the Constitution provided for their election by the state legislatures), passage of antitrust laws (to combat the monopolistic control of American business), and implementation of the eight-hour workday. Since the early 1900s, political candidates and ideas have continued to be described as populist, meaning they favor the rights of and uphold the beliefs and values of the common people.

What was the Progressive movement?

The Progressive movement was a campaign for reform on every level—social, political, and economic—in the United States. It began during the economic depression created by the financial crisis called the “Panic of 1873” and lasted until 1917, when America entered World War I (1914–1918).

During the first 100 years of the U.S. Constitution (1788), federal lawmakers and justices proved reluctant to get involved in or attempt to regulate private businesses. This policy of noninterference had allowed the gap to widen between rich and poor. The turn of the century was a time in America when early industrialists amassed great fortunes and built fantastic mansions, while many workers and farmers struggled to earn a living.

In urban areas, millions lived in overcrowded tenement buildings in which the living conditions were often squalid. Millions of immigrants were entering the country, and many found it impossible to lift themselves out of poverty. Observing these problems, progressive-minded reformers, comprised largely of middle-class Americans, women, and journalists (often called “muckrakers”), began reform campaigns at the local and state levels, eventually affecting changes at the federal level.

Progressives favored many of the ideas that had previously been espoused by the Populists, including antitrust legislation to bust up the monopolies and a graduated income tax to more adequately collect public funds from the nation’s well-to-do businessmen. Additionally, Progressives combated corrupt local governments; dirty and dangerous working conditions in factories, mines, and fields; and inner-city blight. The minimum wage, the Pure Food and Drug Act, and Chicago’s Hull House (which served as “an incubator for the American social work movement”) are part of the legacy of the Progressive movement.

When did the U.S. labor movement begin?

It began in the early 1800s, when skilled workers, such as carpenters and blacksmiths, banded together in local organizations with the goal of securing better wages. By the time of the Civil War, the first national unions had been founded—again by skilled workers. However, many of these early labor organizations struggled to gain widespread support and soon fell apart. But by the end of the century, several national unions, including the United Mine Workers (1890) and the American Railway Union (1893), emerged.

In the last two decades of the 1800s, violence accompanied labor protests and strikes, while opposition to the unions mounted. Companies shared blacklists of the names of workers suspected of union activities; hired armed guards to forcibly break strikes; and retained lawyers to successfully invoke the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890) to crush strikes.

However, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act was being misused. The act was designed to break up large corporations. Now, it was being used against unions, which was not the intent of the lawmakers who had passed the Sherman Act.

In the early decades of the 1900s, unions made advances, but many Americans continued to view organizers and members as radicals. The climate changed for the unions during the Great Depression (1929–1941). With so many Americans out of work, many blamed business leaders for the economy’s failure and began to view the unions in a new light—as organizations created to protect the interests of workers.

In 1935, the federal government strengthened the unions’ cause in passing the National Labor Relations Act (also called the Wagner Act), protecting the rights to organize and to bargain collectively (when worker representatives, usually labor union representatives, negotiate with employers). The legislation also set up the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which is supposed to penalize companies that engage in unfair labor practices.

Unions grew increasingly powerful over the next decade, and by 1945, more than one-third of all nonagricultural workers belonged to a union. Having made important gains during World War II, including hospital insurance coverage, paid vacations and holidays, and pensions, union leaders continued to urge workers to strike to gain more ground—something leaders felt was the worker’s right amid the unprecedented prosperity of the postwar era.

But strikes soon impacted the life of the average American, and consumers faulted the unions for shortages of consumer goods, suspension of services, and inflated prices. Congress responded by passing the Labor-Management Relations Act (or the Taft-Hartley Act) in 1947, which limits the impact of unions by prohibiting certain kinds of strikes, setting rules for how unions could organize workers, and establishing guidelines for how strikes that may impact the nation’s health or safety are to be handled.

The first national union of note was the Knights of Labor, founded by garment workers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1869. Recruiting women, blacks, immigrants, and unskilled and semiskilled workers alike, the Knights of Labor’s open-membership policy provided the organization with a broad base of support, something previous labor unions, which had limited membership based on craft or skill, lacked. In other words, open membership meant that any worker could join. Previously, unions were organized by industry, such as railway workers and garment workers, or by trade, such as carpenters and laborers.

The official seal of the Knights of Labor bears the motto: “That Is the Most Perfect Government in Which an Injury to One Is the Concern of All.”

The Knights of Labor set its objectives on instituting the eight-hour workday, prohibiting child labor (under age fourteen), instituting equal opportunities and wages for women laborers, and abolishing convict labor. The group became involved in numerous strikes from the late 1870s to the mid-1880s.

At the same time, a faction of moderates within the organization was growing, and in 1883, it elected American machinist Terence Powderly (1849–1924) as president. Under Powderly’s leadership, the Knights of Labor began to splinter. Moderates pursued a conciliatory policy in labor disputes, supporting the establishment of labor bureaus and public arbitration systems; radicals not only opposed the policy of open membership, they strongly supported strikes as a means of achieving immediate goals—including a one-day general strike to demand implementation of an eight-hour workday.

What happened in Haymarket Square in Chicago?

In May 1886, workers demonstrating in Chicago’s Haymarket Square attracted a crowd of some 1,500 people. When police arrived to disperse them, a bomb exploded, and rioting ensued. Eleven people were killed, and more than 1,000 were injured in the melee.

For many Americans, the event linked the labor movement with anarchy. That same year, several factions of the Knights of Labor seceded from the union to join the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The Knights of Labor remained intact for three more decades before the organization officially dissolved in 1917, by which time the group had been overshadowed by the AFL and other unions.

How old is the AFL-CIO?

The roots of the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), today a federation of national unions, date to 1881, when the Federation of Organized Trade and Labor Unions was formed, representing some 50,000 members. It reorganized in 1886 as the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and elected Samuel Gompers (1850–1924) president.

Unlike the open-membership policy of the Knights of Labor, the AFL determined to organize by craft. At the outset, its member unions included a total of 140,000 skilled laborers. Gompers had been active in labor for more than two decades. Once chosen as president of the AFL, Gompers remained in that office until his death in 1924. During this nearly forty-year period, he shaped the labor federation and helped it make strides by determining a general policy that allowed member unions autonomy.

Unlike the Knights of Labor, which pursued long-term goals, the AFL focused its efforts on specific, short-term goals, such as higher wages, shorter hours, and the right to bargain collectively (when an employer agrees to negotiate with worker/union representatives).

In the 1890s, the AFL was weakened by labor violence, which evoked public fears. A July 1892 strike at the Carnegie Steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, turned into a riot between angry steelworkers and Pinkerton guards. The militia was called in to monitor the strike, which five months later ended in failure for the AFL-affiliated steelworkers. Nevertheless, under Gompers’s leadership, membership of the AFL grew to more than one million by 1901 and to 2.5 million by 1917, when it included 111 national unions and 27,000 local unions.

The AFL-CIO headquarters is located in Washington, D.C. Representing about twelve million employees and retirees, the AFL-CIO is the largest federation of unions in America.

The federation collected dues from its members, creating a fund to aid striking workers. The organization avoided party politics, instead seeking out and supporting advocates regardless of political affiliation. The AFL worked to support the establishment of the U.S. Department of Labor (1913), which administers and enforces statutes promoting the welfare and advancement of the American workforce, and the passage of the Clayton Anti-Trust Act (1914), which strengthened the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890, eventually delivering a blow to monopolies.

The CIO was founded in 1938. In the early 1930s, several AFL unions banded together as the Committee for Industrial Organizations and successfully conducted campaigns to sign up new members in mass-production facilities, such as the automobile, steel, and rubber industries. Since these initiatives (which resulted in millions of new members) were against the AFL policy of signing up only skilled laborers by craft (the CIO had reached out to all industrial workers regardless of skill level or craft), a schism resulted within the AFL. The unions that had participated in the CIO membership drive were expelled from the AFL. The CIO established itself as a federation in 1938, officially changing its name to the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

In 1955, amid a climate of increasing anti-unionism, the AFL and CIO rejoined to form one strong voice. Today, the organization has craft and industrial affiliates at the international, national, state, and local levels, with membership totaling in the millions.

Who were the Wobblies?

The Wobblies were the early radical members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a union founded in 1905 by the leaders of forty-three labor organizations. The group pursued short-term goals via strikes and acts of sabotage as well as the long-term goal of overthrowing capitalism and rebuilding society based on socialist principles. One IWW organizer proclaimed that the “final aim is revolution.” Their extremist views and tactics attracted national attention, making IWW and Wobblies household terms during the early decades of the twentieth century.

Founded and led by miner and socialist William “Big Bill” Haywood (1869–1928) and mine workers agitator Mary “Mother” Jones (1830–1930), the IWW aimed to unite all workers in a camp, mine, or factory for the eventual takeover of the industrial facility. The union organized strikes in lumber and mining camps in the West, in the steel mills of Pennsylvania, and in the textile mills of New England. The leadership advocated the use of violence to achieve its revolutionary goals and opposed mediation (negotiations moderated by a neutral third party), collective bargaining (bargaining between worker representatives and an employer), and arbitration (third-party mediation). The group declined during World War I (1914–1918), when the IWW led strikes that were suppressed by the federal government. The organization’s leaders were arrested, and the organization weakened. Haywood was convicted of sedition (inciting resistance to lawful authority) but managed to escape the country. He died in the Soviet Union, where he was given a hero’s burial for his socialist views.

The IWW never rose again to the prominent status of its early controversial days. Today, although much smaller in size, the IWW continues to promote its original goal of organizing workers by industry rather than trade. (Its website is iww.org.)

Who was Eugene Debs?

Eugene Debs (1855–1926) was a radical labor leader who in 1893 founded the American Railway Union (ARU), an industrial union for all railroad workers. Debs was a charismatic speaker, but he was also a controversial figure. In 1894, workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company, which manufactured railcars in Pullman, Illinois (near Chicago), went on strike to protest a significant reduction in their wages. Pullman was a model “company town,” where the railcar manufacturer, founded by American inventor George W. Pullman (1831–1897), owned all the land and buildings and ran the school, bank, and utilities.

In 1893, in order to maintain profits following declining revenues, the Pullman Company cut workers’ wages by 25 to 40 percent but did not adjust rent and prices in the town, forcing many employees and their families into deprivation. In May 1894, a labor committee approached Pullman Company management to resolve the situation. The company, which had always refused to negotiate with employees, responded by firing the labor committee members. The firings incited a strike of all 3,300 Pullman workers. In support of the labor effort, Eugene Debs assumed leadership of the strike (some Pullman employees had joined the ARU in 1894) and directed all ARU members not to haul any Pullman cars.

Trade unionist, political activist, and socialist Eugene Debs was a founder of the Industrial Workers of the World and ran five times for president of the United States.

A general rail strike followed, which paralyzed transportation across the country. In response to what was now being called “Debs’ rebellion,” on July 2, 1894, a federal judge ordered all workers to return to the job. When the ARU refused to comply, U.S. president Grover Cleveland (1837–1908) ordered federal troops to break the strike with the justification that it interfered with mail delivery. The intervention turned violent.

Despite public protest, Debs, who was tried for contempt of court and conspiracy, was imprisoned in 1895 for having violated the court order. Debs later proclaimed himself a socialist and became leader of the American Left, running unsuccessfully for president as the Socialist Party candidate in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920.

He was arrested again in 1918 after giving a speech in Canton, Ohio, in which he criticized the U.S. war effort and entry into World War I. He was convicted of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 because he compared the draft to slavery and told members of the crowd that they were no better than mere cannon fodder. (The Espionage Act took away the right of free speech for saying anything negative about the war effort.) President Warren G. Harding (1865–1923) commuted his sentence in 1921. Today, the life of Debs can be explored at the Eugene V. Debs Museum in Terre Haute, Indiana.

What happened at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911?

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory occupied the top three floors of a Manhattan office building. (The building still stands as the Brown Building at 23–29 Washington Place in Greenwich Village. A “shirtwaist” was a woman’s blouse.) The factory was one of the most successful garment factories in New York City, employing some 1,000 workers, mostly immigrant women. But the conditions were hazardous: The space was cramped, accessible only via stairwells and hallways so narrow that people had to pass single file; only one of the four elevators was regularly in service; the cutting machines in the workroom were gas-powered; scraps of fabric littered the work areas; the water barrels (for use in case of fire) were not kept full; and the no-smoking rule was not strictly enforced. Many exit doors were locked. In short, it was an accident waiting to happen.

On Saturday, March 25, 1911, fire broke out. A total of 146 garment workers—mostly immigrant women aged fourteen to twenty-three—died. However, smoke and fire were not the only causes of death. In the panicked escape, people were trampled, fell in elevator shafts, jumped several stories to the pavement below, and were killed when a fire escape melted and collapsed.

Poor working conditions in New York City’s garment district led to the tragedy of the 1911 Triangle Shirwaist Factory fire that killed 146 people. It became a rallying cry for the labor movement.

The disaster became a rallying cry for the labor movement. Tens of thousands of people marched in New York City in tribute to those who had died, calling attention to the grave social problems of the day. New York State enacted legislation, and New York City created ordinances calling for fire-safety reforms in factories, including the requirement to install sprinkler systems. The incident illustrated the importance of government regulation to create safe working conditions in factories.

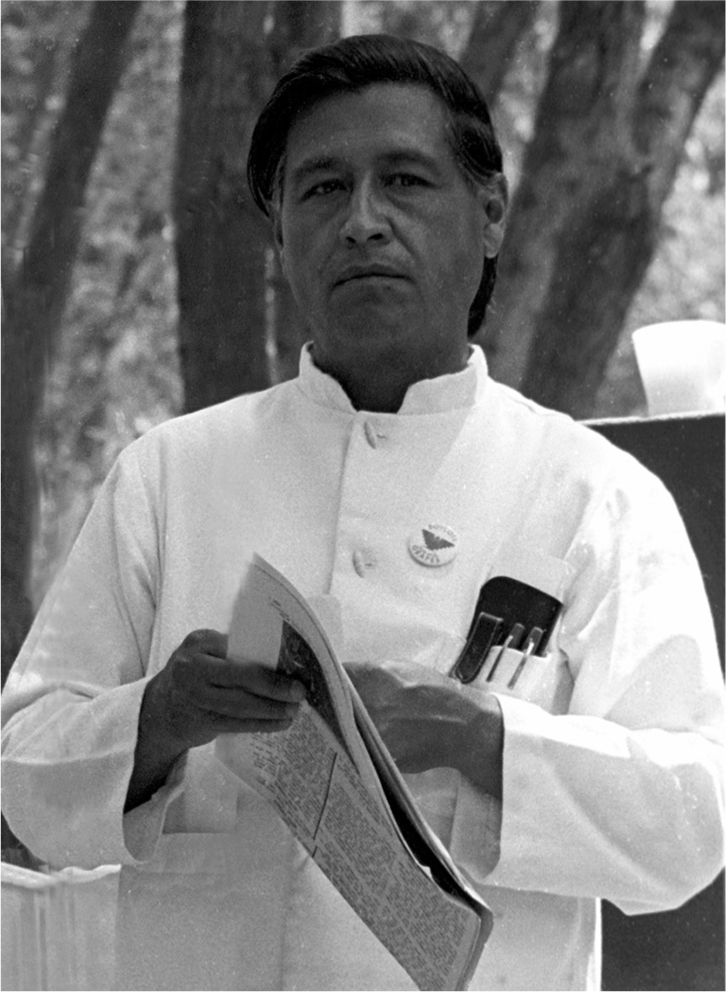

Who was Cesar Chavez?

Mexican American farmworker Cesar Chavez (1927–1993) was a labor union organizer and spokesperson of the poor. Born in Arizona, his family lost their farm when he was just ten years old; they became migrant workers in California, where farm production—particularly of grape crops—depended on temporary laborers. Chavez knew the migrant worker’s life intimately, and, as a young man, he began working to improve conditions for his people. In 1962, he organized California grape pickers into the National Farm Workers Association.

Cesar Chavez was a key leader in organizing farmworkers in California. The state honors him annually on Cesar Chavez Day, which is March 31.

Four years later, this union merged with another to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC). An impassioned speaker known for squishing bunches of grapes in his hands as he delivered his messages, Chavez went on to lead a nationwide boycott of table grapes since growers had refused to accept the collective bargaining of the UFWOC. By the close of the 1970s, California growers of all crops had accepted the migrant workers’ union, known since 1973 as the

United Farm Workers of America (UFW). Like Martin Luther King Jr., Chavez maintained that nonviolent protest was the key to achieving change.

Migrant farmworkers continue to play an important role in the American economy. There are perhaps two to three million farmworkers in America who do work such as handpicking fruits and vegetables. The work is typically physically hard, involving long hours and often unhealthy or dangerous working conditions. Despite some success of workers’ unions, many migrant workers still work in harsh conditions for low wages.

Migrant farmworkers are one of the key reasons that many of the fruits and vegetables we buy are not very expensive.

What is “right to work”?

In a union shop, any new worker who is employed has to join the union and pay dues to support the union. The union must protect the worker’s rights, and the worker receives the benefits of better wages and working conditions negotiated by the union. In the twenty-seven states that have right-to-work laws, unions cannot negotiate contracts with company managers to require new workers to join the union.

Although “right to work” is often promoted as a freedom issue—that a new worker should be free whether or not to choose to join a union—the real reason for right-towork laws is to weaken the power of unions to fight for better pay and better conditions for workers. Right-to-work laws reduce union membership and reduce the dues money that supports the unions. However, in right-to-work states, the workers who do not join the union and pay union dues still get the benefits that the unions fought for, such as better pay and union help in settling problems between a worker and employer.

How is the labor movement doing today?

The labor movement in the United States has been struggling for decades. The main reason is that so many unionized jobs have been shipped overseas, where the labor is much cheaper. The NAFTA agreement (1994) sped up the process. Also, many companies have moved their factories to right-to-work states, where unions have less power.

Furthermore, many businesses have worked hard to keep unions out. For example, the largest business employer in the United States is Walmart, with over 1.5 million workers. However, Walmart has worked very hard to keep those workers from unionizing. Also, political forces, especially conservative voices, have worked to sour many people’s attitudes toward labor unions.

Lastly, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is an agency of the federal government that is supposed to protect workers’ rights to organize. Under Republican administrations, however, it has often promoted the interests of businesses while neglecting the rights of workers.

What are the gains made by unions that benefit most workers?

Unions fought very hard for better working conditions and pay, yet many people, including many nonunion workers, have benefited from them. Here is a list of some of the benefits that unions have provided:

• The eight-hour workday

• The forty-hour work week

• A two-day weekend

• Safe working conditions

• The right to not be fired arbitrarily

• Health insurance

• Retirement benefits

• A banning of child labor

• Good wages so one can enter the middle class

As mentioned above, many good union jobs in America have disappeared as manufacturing has shifted overseas. In most places where these jobs have gone, the workers do not have the benefits listed above. Many of the manufactured goods that Americans consume are made by workers whose rights are not protected. That is why the labor of these workers is so cheap and why the goods we buy are so cheap.

COUNTERCULTURE, CONSUMERISM, AND THE ENVIRONMENT

What was the Beat movement?

The post-World War II era bred unprecedented prosperity and an uneasy peace in the United States. Out of this environment rose the Beat generation, alienated youths who rejected society’s new materialism and threw off its “square” attitudes to reinvent “cool.” The Beat generation of the 1950s bucked convention, embraced iconoclasm, and attracted attention. Mainstream society viewed them as anarchists and degenerates. But many American youths listened to and read the ideas of its leaders, including writers Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Jack Kerouac, whose novel On the Road (1957) was the bible of the Beat movement.

The “Beatniks,” as they were dubbed by their critics, believed in peace, civil rights, and radical protest as a vehicle for change. They also embraced drugs, mystical (Eastern) religions, and sexual freedom—all controversial ideas during the postwar era. Beat writers and artists found their homes in communities like San Francisco’s North Beach, Los Angeles’s Venice Beach, and New York City’s Greenwich Village. The movement merged—or, some would argue, gave birth to—the counterculture movements of the 1960s, including the hippies. Beat literature is the movement’s legacy.

Young members of the counterculture of the 1960s and early 1970s were often referred to as “hippies.” They were opposed to war, advocated free love, and experimented with sex, drugs, music, and art.

Who were the hippies?

Most hippies of the 1960s and 1970s were young (fifteen to twenty-five years old), white, and from middle-class families. The counterculture (antiestablishment) movement advocated freedom, peace, love, and beauty. Having dropped out (of modern society) and tuned in (to their own feelings), these flower children were as well known for their political and social beliefs as they were for their controversial lifestyle. (Some hippies were called “flower children” since they saw the flower as a symbol of beauty, peace, and natural simplicity.)

Hippies opposed American involvement in the Vietnam War and rejected an industrialized society that seemed to care only about money; they favored personal simplicity, sometimes living in small communes where possessions and work were shared, or living an itinerant lifestyle, in which day-to-day responsibilities were few if any; they wore tattered jeans and bright clothing usually of natural fabrics, grew their hair, braided beads into their locks, walked around barefoot or in sandals, and listened to a new generation of artists, including the Beatles, the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Bob Dylan, and Joan Baez.

The hippie movement was in part shaped by the U.S. military draft. Hippie calls for freedom were often in opposition to the draft of young men to fight in the unpopular Vietnam War.

Some hippies were also known for their drug use. Experimenting with marijuana and LSD, some hoped to gain profound insights or even achieve salvation through the drug experience—something hippie guru Timothy Leary (1920–1996) told them was possible. New York City’s East Village and San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood became havens of this counterculture. The movement began on American soil but was soon embraced elsewhere as well—principally in Canada and Great Britain.

What happened to the hippies?

The conflict in Vietnam ended, flower children grew older, drugs took their toll on some, and by 1980 (and the advent of AIDS), the idea of free love fell into disfavor. Still, a few continued to lead an alternative lifestyle, while at the opposite end of the spectrum, others bought back into the establishment. Still others adapted their flower-child beliefs to the ever-changing world around them and got on with their lives, working at jobs and raising children in the most socially and politically conscious way possible.

What was Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical?

Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical was the popular rock musical that caught the spirit of the time. With the book and lyrics written by Gerome Ragni and James Rado and music written by Galt MacDermot, Hair opened on Broadway in 1968, with songs about race relations, love, sex, drugs, the military draft, air pollution, Vietnam, and astrology.

Act I ended with a very brief scene of the cast onstage in the nude. The scene reflected the freer attitudes toward sexuality of the period. The scene may have also been a ploy to draw bigger audiences, who came to see the nude scene, or because of the controversy about the scene.

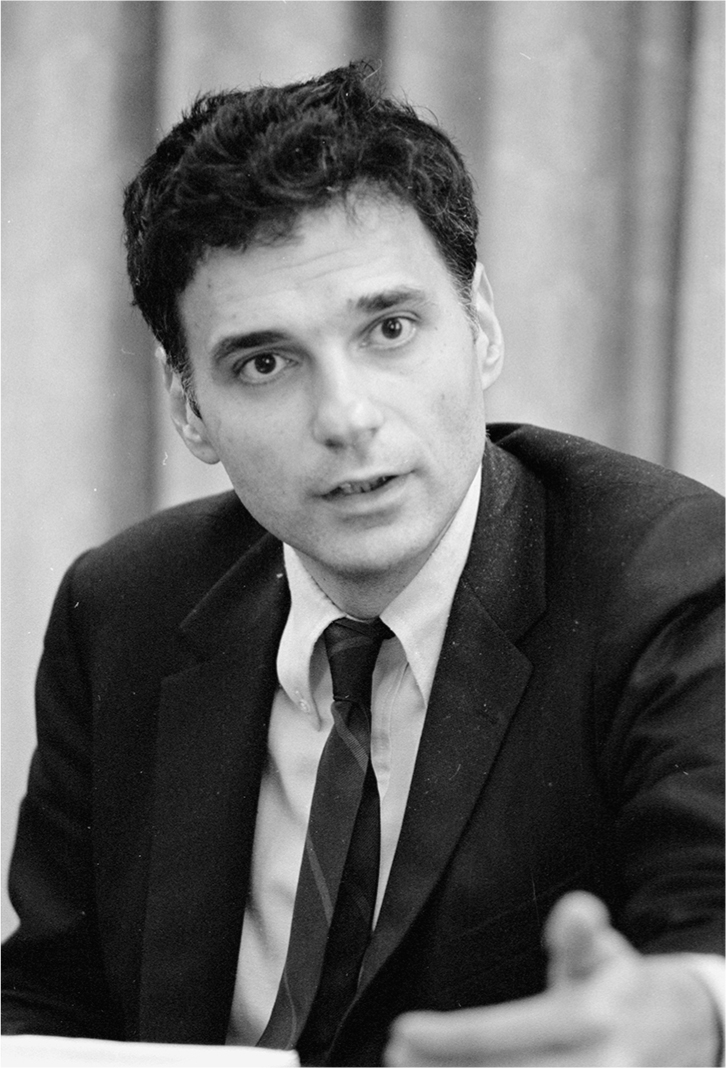

Who is Ralph Nader?

Ralph Nader (1934–), an American lawyer, has become the best-known consumer advocate ever. He has even run for president several times. With the help of his research team, called Nader’s Raiders, he wrote the landmark book Unsafe at Any Speed in 1965; it charged that many automobiles were not as safe as they should be or as consumers had the right to expect them to be. In part, the book was responsible for passage in 1966 of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, which set motor vehicle safety standards. Nader continued his watchdog work, founding the Public Citizen organization, which researches consumer products, promotes consumer awareness, and works to influence legislators to improve consumer safety. (Public Citizen disassociated itself from Ralph Nader after his 2000 run for president.)

Ralph Nader (shown here in 1975) has been a dominant force in the consumer-protection movement. An attorney, author, lecturer, and former presidential candidate, he is best known for fighting for carsafety regulations.

Who were some advocates for consumers before Ralph Nader?

While Nader may be the most recognizable face of consumer advocacy, the movement’s roots predate his activism. As the consumer age dawned at the end of the 1800s and early 1900s, when mass-production techniques came into wide use, some observers decried industry standards (or lack thereof) that put the public who used their products at risk. The muckraking journalists of the early twentieth century disclosed harmful or careless practices of early industry, raising awareness and bringing about needed reforms. The practices attacked included things such as poisons put in foods and so-called medicines. Upton Sinclair (1878–1968) penned the highly influential novel The Jungle (1906), revealing scandalous and unsanitary conditions at meat-packing plants.

The public was outraged; upon reading Sinclair’s work, President Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) ordered an investigation. Finding the novelist’s descriptions to be true to life, the government moved quickly to pass both the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in 1906. Industry watchdogs continued their work in the early decades of the century. For instance, in 1929, Consumers’ Research, Inc., was founded, and in 1936, Consumers Union (now Consumer Reports) formed; both independent organizations test and rate consumer products. (The monthly magazine Consumer Reports can be read online or in the print version.) Such consumer advocacy has served to heighten public awareness, compelling many industries to make changes and improve the safety of products in general.

More consumer-protection laws were enacted in the 1960s and 1970s. Under President Barack Obama (1961–), an effort was made to strengthen consumer protections, especially against such things as predatory loans, for-profit universities that give inadequate educations yet leave students with large debts, and high interest rates on consumer debt.

Under the administration of President Donald Trump (1946–), there has been a systematic effort to remove many regulations that protect consumers. The Trump Administration, seeing government regulation as bad for business, has ignored over a hundred years of history where the U.S. government has regulated industries to encourage good business practices and restrain businesses that make profits by taking advantage of consumers. For example, the Trump Administration wants to remove the number of government inspectors at meat-packing plants. It has also removed regulations against predatory lenders and predatory for-profit universities.

What is the Kyoto Protocol?

It was an environmental agreement signed by 141 nations that agreed to work to slow global warming by limiting emissions, cutting them by 5.2 percent by 2012. Each nation has its own target to meet. The protocol was drawn up on December 11, 1997, in the ancient capital of Kyoto, Japan, and went into effect on February 16, 2005. The United States is not among the signatories due to American officials saying that the agreement is flawed because large developing countries, including India and China, were not immediately required to meet specific targets for reduction. Upon the protocol’s enactment, Japan’s prime minister called on nonsignatory nations to rethink their participation, saying that there was a need for a “common framework to stop global warming.” Environmentalists echoed this call to action.

What did Silent Spring have to do with the environmental protection movement?

The 1962 book Silent Spring, by American ecologist Rachel Carson (1907–1964), cautioned the world on the ill effects of chemicals on the environment. Carson argued that pollution and the use of chemicals, particularly pesticides, would result in less diversity of life. The best-selling book had wide influence, raising awareness of environmental issues and launching green (environmental protection) movements in many industrialized nations.

What is the Paris Agreement?

The next international agreement to take action to slow global warming and climate change was the Paris Agreement, also known as the Paris Accord, adopted in 2015. The agreement calls for nations to take significant steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to take steps to prepare for the effects of climate change. By 2015, 195 countries—the vast majority of countries—had signed it.

In 2017, the Trump Administration gave notice that the United States would leave the Paris Agreement. President Donald Trump has repeatedly denied that climate change is happening and has called it a “hoax.” (There is a delay in withdrawing built into the agreement, which means the United States cannot withdraw until perhaps late 2020.)

Demonstrators march in the city of Bayda, Libya, during the summer of 2011, the time of the Arab Spring, when multiple nations saw despotic governments overthrown or drastically changed.

Unfortunately, many of the countries who signed the Paris Agreement have not taken enough action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to the levels pledged in the agreement.

(Global warming and climate change will be discussed in more detail in the “Disasters” chapter.)

What is the Arab Spring?

The Arab Spring was a movement in the Middle East that began in 2010 seeking to bring about revolutionary change and a more democratic environment in countries such as Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Yemen. The protestors sought to rally against government repression and suppression of social media communications.

The first wave of protests began in Tunisia in December 2010 and then spread to Algeria, Jordan, and Egypt. Protests in Libya led to the removal of longtime repressive leader Muammar Gaddafi (1942–2011). A protest in Lebanon in December 2011 led to a significant increase in worker wages. Time magazine named “the Protester” its Person of the Year in December 2011 partly as a result of the Arab Spring movement.

However, there was reaction to these calls for reform and democracy of the Arab Spring, and in the wake came what some have called the “Arab Winter,” with civil war and/or more oppressive governments in the countries involved. (Only Tunisia has made progress toward democracy.)

THE ANTISLAVERY MOVEMENT TODAY

Is there slavery today?

Yes, slavery continues into the twenty-first century. Estimates range from twenty-one million to forty-six million enslaved humans in the world today, with perhaps ten million of these being children. (At the time of the American Civil War, there were four million enslaved people in America.) It is often called “human trafficking.” It is impossible to get exact numbers because there is no precise definition of slavery. Also, since slavery is illegal, much of it is hidden, making it difficult to count how many slaves exist. Making it worse is that enslaved humans are cheap today: they can be bought for as little as $90. Humans are enslaved mostly so the enslavers can make money.

Men, women, and children, especially in developing countries, are forced into labor in sweatshops and fields and into prostitution in brothels. In desperately poor regions of the world, families sell their children into slave labor and forced prostitution.

Sex trafficking is one type of slavery. It is estimated that between 10,000 and 50,000 women and girls are trafficked in the United States each year.

What are the typical types of slavery today?

There are several common types of slavery today:

• Bonded labor (debt bondage)

• Domestic servitude

• Sex trafficking

• Child labor

• Forced marriage

• Government-forced labor

• Prison labor

Bonded labor (debt bondage) is the most common form of slavery of people. These are people forced to work to pay off debts. They cannot leave until the debt is paid, which often never happens. Making it worse is that in many places, economic forces give people so few choices that they end up deeper in debt. This often results in unpaid debts being passed on to future generations.

Domestic servitude happens when one is employed in a home as a maid, nanny, or caregiver of the elderly or infirmed but is unable to leave the situation. These people are often immigrants who were lured into jobs with promises of education, which are never fulfilled. Domestic workers in these situations often become victims of sexual and physical abuse.

LGBTQIA RIGHTS

What is meant by LGBTQIA?

The abbreviation stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Queer (or Questioning), Intersex, and Asexual. The I and A were more recent additions in an attempt to include all people.

When did the gay rights movement begin?

On June 28, 1969, New York City police raided a gay bar, the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village in Manhattan. At that time, one could be arrested for being gay or being in a place that catered to gays, so few bars openly welcomed gays. Cross-dressing was also illegal. The Stonewall Inn was one of the few places that welcomed gays and lesbians, drag queens, transgender people, male prostitutes, and homeless youth. The bar was run by the Mafia, who had paid off the police to leave it alone. The police did occasionally raid the Stonewall Inn, but usually, the bar knew in advance when they were coming.

However, on that June evening in 1969, when the police showed up, the patrons of the bar, tired of police harassment, resisted. The situation quickly got out of hand, and a riot ensued. More protests and rioting took place the next day as people began to organize to fight for their rights.

This was the beginning of the gay rights movement, and this is why gay pride parades take place in June each year across the country and around the world. The first gay pride marches took place in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles on June 28, 1970.

Harvey Milk is shown sitting at the desk of Mayor George Moscone of San Francisco. He filled in for the mayor for a day but was usually serving in his Board of Supervisors position.

The 1969 event has been called the Stonewall Uprising. The PBS 2010 documentary Stonewall Uprising tells the whole story.

Who was Harvey Milk?

Harvey Milk (1930–1978) was an activist and politician. He was the first openly gay elected official in California. He had moved to the Castro District of San Francisco in 1972, an area where many gay and bisexual men lived. In 1977, he was elected a city supervisor in San Francisco.

One of his accomplishments was to get a law passed and to change attitudes so that dog owners would clean up after their dog. Harvey played a key role in fighting for gay rights, and as a city supervisor, he fought for legislation to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Tragically, Milk and San Francisco mayor George Moscone were shot and killed by a former supervisor, Dan White, a troubled man. Harvey Milk became a martyr for the cause of gay rights.

Milk is a 2008 film biography of Harvey Milk, who is played by Sean Penn.

What is the Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDoR)?

November 20 is a day to remember and memorialize transgender people who have been murdered as a result of transphobia. The murder of transgender people is a problem worldwide. In the United States, there were twenty-four such murders in 2018 and twenty-four in 2019.

What is the AIDS Quilt?

The quilt was started in 1985 to draw awareness to the AIDS epidemic and also to remember those who died of AIDS. It is made of 3’ x 6’ panels. Each is created by friends, partners, or family members of those who died of AIDS. It is also known as the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. There are over 48,000 panels. The AIDS quilt web page lists upcoming displays of portions of the quilt.

The quilt played an important educational role in the early part of the AIDS epidemic. It helped lead to a more honest discussion of the scale of the illness.

OTHER RECENT MOVEMENTS

What is the Me Too or #MeToo movement?

The Me Too movement fights against sexual assault and sexual harassment. The phrase was originally created by activist Tarana Burke (1973–) in 2006. She is a survivor of sexual harassment.

In 2017, as multiple accusations of sexual crimes were made against film producer Harvey Weinstein (1952–), the Me Too term became a hashtag on social media. The goal of using the hashtag was to make people aware of the many, many victims of sexual harassment. The movement has spread worldwide.

What is the Occupy movement?

The Occupy movement was an international movement designed to address social and economic disparities and to make the economic power structure more equitable. The Occupy movement used the slogan “We are the 99 percent,” signifying that the power structure and financial empires of world governments serve the interests of the extremely wealthy 1 percent of the world.

Occupy movements or protests occurred throughout the world. For example, 200,000 people protested in Rome, Italy, in October 2011 against economic conditions. Occupy Wall Street, which took place in the Wall Street District in New York City’s Zuccotti Park in September 2011, marked the movement in the United States.

Occupy movements sprang up in various cities across the United States. Occupiers camped out on government property, carrying signs and creating symbolic tents to send the message that they will occupy government land until the government responds to the financial wrongs and abuses of the country.

However, in the United States, the occupy encampments were spied on by authorities such as the FBI and then closed by police. Many members of the movement saw this as proof that the ruling elite had the power to suppress free speech and the right to assemble to protest.

What is the Black Lives Matter movement?

The movement began in 2013, when the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was used after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who had shot and killed African American teen Trayvon Martin in February 2012. The movement gained national attention after its demonstrations following the 2014 deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City. Both black men were killed by white police officers.

The intent of the movement is to draw attention to frequent deaths of African Americans and, in particular, those who die at the hands of police officers.

What is the Tea Party movement?

The Tea Party, formed in 2009 and named for the Boston Tea Party of 1773, has been vocal in calling for lower taxes and reduced government spending. In particular, the Tea Party opposed the policies of President Barack Obama (president from 2009 to 2017), such as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) and the Affordable Care Act. In particular, Tea Party members opposed the increasing federal debt. Over the next years, they held numerous rallies and protests and got a number of Tea Party supporters into Congress.

Although many supported the election of Donald Trump in 2016, reducing the federal debt seems no longer to be an issue, as the debt has climbed to record levels. In July 2019, Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky declared the Tea Party dead, as the U.S. government debt kept growing.

What is the Southern Poverty Law Center?

The Southern Poverty Law Center is a nonprofit organization that uses the courts to fight white nationalists and extremist groups. It also works to identify and track hate groups and educate citizens about the growing presence of these groups. The center identified 940 groups in 2019. (The list of these groups can be found on its web page, https://www.splcenter.org/.)