Matter, though divisible in an extreme degree, is nevertheless not infinitely divisible. That is, there must be some point beyond which we cannot go in the division of matter.…I have chosen the word “atom” to signify these ultimate particles.

—John Dalton1

FROM ALCHEMY TO CHEMISTRY

For over two thousand years, the atomic theory of matter had no empirical confirmation. Nevertheless, the model of particles moving around in empty space was fundamental to Newtonian mechanics and the scientific revolution that followed. Finally, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, experiments in chemistry began to provide indirect evidence in support of the atomic picture.

Chemistry grew, at least in part, out of the ancient art of alchemy, which was characterized by attempts to transmute base metals into gold or silver. However, alchemy as practiced from the Middle Ages well into the seventeenth century was motivated by more than a desire for instant wealth. Alchemists sought a magical substance called the “philosopher's stone” that they hoped would be the key to transforming imperfect, corruptible substances into that which is in a perfect, incorruptible state. It was thought that the philosopher's stone would cure illness and even generate immortality. It was the “elixir of life.”

Alchemy was practiced in ancient Egypt, Greece, India, and China, and flourished in medieval Europe and the Arabic empire. Indeed, the Islamic scholar J bir ibn Hay

bir ibn Hay n (ca. 815), known in the West as Geber the Alchemist, created much of what we now regard as the laboratory practice of chemistry while he practiced alchemy.2 Note that the word alchemy is a combination of the Arabic al (the) and the Greek chimeia (chemistry).

n (ca. 815), known in the West as Geber the Alchemist, created much of what we now regard as the laboratory practice of chemistry while he practiced alchemy.2 Note that the word alchemy is a combination of the Arabic al (the) and the Greek chimeia (chemistry).

Everywhere alchemy was practiced, it was closely tied to the indigenous religious and spiritual systems. It was not science as we know it today. While the Catholic Church generally rejected those occult beliefs not part of its own dogma, alchemy found approval from several popes as well as from Martin Luther (1483–1546) and other Christian leaders. Pope John XXII (1244–1334) was a practicing alchemist. The famous scholar and saint, Albert the Great (ca. 1200–1280), who tried to reconcile science and religion, was a master alchemist. He passed on his knowledge to his student, the even more famous scholar and saint Thomas Aquinas, who wrote several treatises on alchemy.

In England, Henry VIII (1491–1547) and Elizabeth I (1533–1603) actively supported alchemy. Queen Elizabeth provided funding for one of the most prominent alchemists in history, John Dee (1527–1608). Dee was not only an alchemist but also an accomplished mathematician and astronomer whose positive contributions to these fields, notably celestial navigation, were diminished by his obsession with magic.3 In 1582, Dee claimed an angel gave him a crystal ball that enabled him to communicate with spirits and foretell the future. The actual crystal can be viewed in the British Museum in room 46 of the Tudor collection.4

Alchemy was a strange combination of empirical pseudoscience and mysticism. Alchemists had a vast knowledge of how various materials behave when mixed with other materials and heated. One of the favorite materials was mercury, or quicksilver. Since it looked like silver, it was a good candidate to aid in the manufacture of that precious metal. Indeed, if you dissolve mercury in nitric acid and then mix in some lead, a silvery residue appears. However, the residue turns out to be not silver but quicksilver. What happens is the lead reacts more strongly with the nitric acid, and so the mercury leeches back out.

The endeavors of alchemists could certainly be labeled as “experiments.” However, these experiments were not performed very systematically, and reported observations were usually couched in codes and arcane language to keep any knowledge gained secret, which is an important difference with real science. Although thousands of volumes of alchemic literature going back centuries were in circulation, virtually all of it was useless gibberish.

Although Isaac Newton is immortalized for his physics, he spent more of his time on and wrote more words about alchemy than physics. In a fascinating book titled Isaac Newton: The Last Sorcerer, author Michael White writes:

Like all European alchemists from the Dark Ages to the beginning of the scientific era and beyond, Newton was motivated by a deep-rooted commitment to the notion that alchemical wisdom extended back to ancient times. The Hermetic tradition—the body of alchemical knowledge—was believed to have originated in the mists of time and to have been given to humanity through supernatural agents.5

It never occurred to Newton, the great mechanic and atomist, to take seriously the atomist view of life as being purely the result of the mechanical motions of particles. Newton regarded the philosopher's stone to be the elixir vitae, the miraculous substance of life.

Newton's alchemy was far more careful and systematic than most of the alchemists preceding him, as befits his reputation as the greatest scientist of all time. However, he was still a man of his time, with a strong belief in magic and the supernatural. He despised the Catholic Church, agreeing with the radical Puritan view that it is the antichrist, the devil, and the “Whore of Babylon” of the book of Revelation. He had little more use for the Anglican Church, and although he was Lucasian Professor at Trinity College, Cambridge (the position currently held by cosmologist Stephen Hawking), he dismissed the Trinity as inherently illogical and a corrupt contrivance of the Church.6

Besides Newton's real science and his alchemy, he spent huge amounts of time trying to extract dates for the fulfilling of the prophecies of the Bible, and alchemic history somehow aided in that task. He predicted that the Second Coming of Christ would be in 1948.7 I don't think that followed from the laws of motion.

This is not the only place where Newton's spiritual beliefs impacted his science. For example, he believed the patterns of motion of the planets in the solar system could not be explained scientifically and so God continually adjusted these motions.8

While Newton was dabbling in the occult, his contemporaries, notably Robert Boyle, were in the process of transforming the magical art of alchemy into the science of chemistry. Thus, Newton truly was the “last sorcerer.”

Despite the mystical aspects of alchemy, its experimental practitioners nevertheless accumulated considerable factual knowledge and developed many of the methods that became the modern experimental science of chemistry. As the new science of physics came into being in the seventeenth century, so did the new science of chemistry. Here the key figure was not Newton, who, as we saw, was still mired in the mystical arts, but Boyle. While still doing alchemy himself, in 1661 Boyle published The Sceptical Chymist, where he distinguished chemistry as a separate art from alchemy and medicine.

Boyle was very much an atomist and mechanical philosopher. He introduced what we now call Boyle's law, which says the pressure and volume of an “ideal” gas are inversely proportional for a gas at a fixed temperature. This would form part of the ideal gas law that, as we will see below, would later be derived from and provide empirical evidence for the atomic model.

THE ELEMENTS

Practical chemistry is an ancient art. After all, metallurgy goes back to prehistoric times. A copper axe from 5500 BCE has been found in Serbia. Many of the other metals—gold, silver, lead, iron, tin—that were mined and smelted in ancient times are now identified as chemical elements. When their ores were heated to very high temperatures, they separated out from the rest of the materials in which they were embedded. However, the elements could not be reduced further—that is, until the twentieth century.

Similarly, irreducible substances such as sulfur, mercury, zinc, arsenic, antimony, and chromium were identified for a total of thirteen elements known prior to the Common Era, although they were not recognized as elementary at the time. By 1800, thirty-four elements had been identified, with another fifty uncovered in the nineteenth century. The twentieth century added twenty-nine more elements, of which sixteen were synthesized in particle accelerators. At this writing, five more have been synthesized in the current century. Norman E. Holden of the National Nuclear Data Center at Brookhaven National Laboratory has provided a history of the elements recognized up to 2004.9

Still, prior to the eighteenth century, the ancient belief was widely held that these irreducible materials were not in fact elementary but composed of fire, earth, air, and water. Then, in France, Antoine Lavoisier (1743–1794) showed that water and air were not elementary substances but instead were composed of elements such as hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. He identified oxygen as a component of air and responsible for combustion, disproving the theory that bodies contain a substance called phlogiston that is released during combustion.

Making precise quantitative measurements, Lavoisier demonstrated that the total mass of the substances involved in a chemical reaction does not change between the initial and final state, even though the substances themselves may change. This is the law of conservation of mass that, more than a century later, Einstein would show must be modified because mass can be created and destroyed from energy. This effect is negligible for chemical reactions, and, after Einstein, mass conservation was simply subsumed in the more general principle of conservation of energy.

By the time the nineteenth century opened, chemistry had expunged itself of alchemy, and laboratory chemists focused on careful analytical methods to build up a storehouse of knowledge on the properties of both elements and the compounds that were formed when they combined. The data eventually led to the periodic table of the chemical elements. Proposed in 1869 by Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, it hangs on the walls of all chemistry classrooms today.

THE CHEMICAL ATOMS

In a lecture before the Royal Institution in 1803, John Dalton (1766–1844) proposed an atomic theory of matter that was really not that much different from that of the ancient atomists:

- All matter is composed of atoms.

- Atoms cannot be made or destroyed.

- All atoms of the same element are identical.

- Different elements have different types of atoms.

- Chemical reactions occur when atoms are rearranged.

- Compounds are formed from atoms of the constituent elements.

However, Dalton did have hard, quantitative evidence—from his own experiments and others’—that provided an empirical basis none of the earlier atomists had available to them. He put these together in A New System of Chemical Philosophy, published in 1808.10 Dalton did not, however, assume that the atoms were necessarily particulate in nature.

In 1806 French chemist Joseph Proust (1754–1826) proposed what is called the law of definite proportions, which says that when two elements combine to form a compound, they always do so with the same proportion of mass. For example, when hydrogen and oxygen unite to form water, they always do so in the mass ratio of 1 to 8. Dalton added that the ratio is always a simple proportion of whole numbers, that is, a rational number. This is called the law of multiple proportions.

However, Dalton insisted that the ratio was always the same number for the same two elements, while evidence accumulated that frequently two elements combine into more than a single whole-number ratio. He defined the atomic weight as the mass of an atom in units of the mass of hydrogen. That is, hydrogen is assigned an atomic weight of 1. Dalton assumed that the water molecule is HO, and this implied that the atomic weight of oxygen is 8. With the discovery of hydrogen peroxide, Dalton's assumption implied that its formula was HO2. However, it was eventually figured out that water is H2O (“dihydrogen monoxide”), hydrogen peroxide is H2O2, and the atomic weight of oxygen is not 8 but 16.

Today the atomic weight is defined to be exactly 12 for the carbon atom that has a nucleus containing six protons and six neutrons surrounded by six electrons: C12. This definition is unfortunately anthropocentric. We humans just happen to have a lot of carbon in our bodies.

Various isotopes of carbon exist with different numbers of neutrons in the nucleus. With this definition, the atomic weight of the hydrogen atom is not exactly 1 but 1.00794. However, 1 is sufficiently accurate for our purposes. Atomic weight is also referred to as atomic mass, molecular weight, or molecular mass. I will simply call it atomic weight, even in the case of a molecule composed of many atoms.

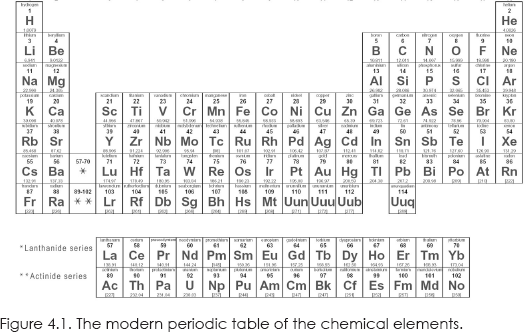

If you look at the periodic table, you will see that the ordering is not by atomic weight. The order number is called the atomic number and in constructing the table, Mendeleev moved some elements around so that they also fell into place based on their chemical properties. Thus we have elements with similar properties arranged vertically, with the very chemically active elements H, Li, Na, K, and the like in the first column and the inert elements He, Ne, Ar, Kr, and the like in the nineteenth column. Actually, the older table that you will still see in some classrooms had just eight columns; the modern table has been expanded to nineteen columns, as shown in figure 4.1.11 It would not be until the chemical atoms were found to have a substructure, which quantum mechanics explained, that the science underlying the periodic table would be understood.

THE CHEMICAL OPPOSITION

That is not to say that the model of atoms and the void was accepted without opposition during the nineteenth century. In fact, the opposition was fierce, especially in France. Many chemists, philosophers, and even a few physicists were far from convinced of the existence of atoms. In an 1836 lecture before the Chemical Society in London, French chemist Jean-Baptiste Dumas (1800–1884) said, “If I were the master, I would outlaw the word ‘atom’ from science, convinced as I am that it goes far beyond experiments.”12

The objection of Dumas and his fellow antiatomists of the time was basically that no one had ever seen an atom or a molecule. Henri Sainte-Claire Deville (1818–1881) wrote: “I accept neither Avogadro's law, nor atoms, nor molecules, nor forces, nor particular states of matter; I absolutely refuse to believe in what I cannot see and can even less imagine.”13 Deville didn't have much of an imagination.

Another French chemist named Marcellin Berthelot (1827–1907) was a dedicated antiatomist who also held a government position that enabled him to suppress the teaching of atomism in French schools well into the twentieth century. As late as the 1960s, governmental decrees required that chemistry be taught through “facts only.” Authors of textbooks complied by relegating the atomic theory to an afterthought, reminiscent of today's America where many high-school textbooks and teachers still present evolution as “just a theory, not a fact.” It is also reminiscent of the Church's order to Galileo to teach heliocentrism as just a theory.

THE PHILOSOPHICAL OPPOSITION

Nineteenth-century theologians had little to say about atomism. The deism and atheism of the seventeenth century had pretty much fizzled after the bloody failure of the French Revolution. The age of reason in Europe was replaced by the romantic movement in literature and art, and by the “Great Awakening” when Protestantism in America turned away from theology and tradition toward emotional and spiritual renewal. The Thomas Jeffersons, Benjamin Franklins, and Denis Diderots were gone, and no one except scientists thought much anymore about science. As today, most scientists preferred it that way. Nineteenth-century atomists were mostly religious believers who stuck to the physics and chemistry and ignored Epicurean atheism. But that did not make Epicurean atheism go away.

Once chemistry was clearly separated from alchemy, it could join physics, which was already fully materialistic as a science that could be pursued independent of one's religious inclinations. Some antiatomists, such as Dumas and Duhem, were fervent Catholics but did not base their arguments on metaphysics.14

The same could not be said about biology. Darwinian evolution certainly caught the attention of educated clergy but was not especially noticed by the general public until the early twentieth century. The role of atoms in evolution also had to await further developments, in particular the discovery of the structure of DNA, which did not occur until 1953.

Several philosophers in the early nineteenth century strongly opposed atomism, notably Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) and Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860). Their objections were based on metaphysics as well as skepticism about the physics.

Hegel's metaphysical objections followed from his notion that reality cannot be separated into parts. And to Hegel, atomism was metaphysics:

Since even today atomism is favored by those physicists who refuse to deal in metaphysics, it must be reminded here that one cannot escape metaphysics, or, more specifically, the reduction of nature to thoughts, by throwing oneself into the arms of atomism, since the atom is itself actually a thought, and consequently the apprehension of matter as composed of atoms is a metaphysical apprehension.15

As historian Bernard Pullman points out, since its inception the atomic theory has been dogged by a criticism expressed by Aristotle, Cicero, and even Newton that was brought up again by Hegel: How is it that the latent properties of complex compounds form from atoms just bouncing off one another in the void? It would take quantum mechanics to answer that.16

Schopenhauer's objections were based on his strange philosophy of “the world as will and representation,” of which I could never make any sense.17 So let me just use his own words:

Matter and intellect are two interwoven and complementary entities: they exist only for one another and relative to one another. Matter is a representation of the intellect; the intellect is the only thing, and it is in its representation that matter exists. United, they constitute the world as representation, or Kant's phenomenon, in other words, something secondary. The primary thing is that which manifests itself, the thing in itself, in which we shall learn to recognize will.

As for atomism, Schopenhauer is pitiless. He calls it

a crude materialism, whose self-perception of originality is matched only by its shallowness; disguised as a vital force, which is nothing more than a foolish sham, it pretends to explain manifestations of life by means of physical and chemical forces, to cause them to come from certain mechanical actions of matter, such as position, shape, and motion in space; it purports to reduce all forces in nature to action and reaction.18

Despite all these philosophical objections, the physics and chemistry of atoms would emerge triumphant.