Why Do They Vote That Way?

In January 2005, I was invited to speak to an organization of Democrats in Charlottesville, Virginia, about moral psychology. I welcomed the chance because I had spent much of 2004 as a speechwriter for John Kerry’s failed presidential campaign. Not a paid speechwriter—just a guy who, while walking his dog every evening, mentally rewrote some of Kerry’s ineffectual appeals. For example, in Kerry’s acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, he listed a variety of failures of the administration of George W. Bush and after each one he proclaimed, “America can do better” and “Help is on the way.” The first slogan connected to no moral foundation at all. The second one connected weakly to the Care/harm foundation, but only if you think of America as a nation of helpless citizens who need a Democratic president to care for them.

In my rewrite, Kerry listed a variety of Bush’s campaign promises and after each one he asked, “You gonna pay for that, George?” That simple slogan would have made Bush’s many new programs, coming on top of his tax cuts and vast expenditures on two wars, look like shoplifting rather than generosity. Kerry could have activated the cheater detection modules of the Fairness/cheating foundation.

The message of my talk to the Charlottesville Democrats was simple: Republicans understand moral psychology. Democrats don’t. Republicans have long understood that the elephant is in charge of political behavior, not the rider, and they know how elephants work.1 Their slogans, political commercials, and speeches go straight for the gut, as in the infamous 1988 ad showing a mug shot of a black man, Willie Horton, who committed a brutal murder after being released from prison on a weekend furlough by the “soft-on-crime” Democratic candidate, Governor Michael Dukakis. Democrats have often aimed their appeals more squarely at the rider, emphasizing specific policies and the benefits they’ll bring to you, the voter.

Neither George W. Bush nor his father, George H. W. Bush, had the ability to move audiences to tears, but both had the great fortune to run against cerebral and emotionally cool Democrats (Michael Dukakis, Al Gore, and John Kerry). It is no coincidence that the only Democrat since Franklin Roosevelt to win election and then reelection combined gregariousness and oratorical skill with an almost musical emotionality. Bill Clinton knew how to charm elephants.

Republicans don’t just aim to cause fear, as some Democrats charge. They trigger the full range of intuitions described by Moral Foundations Theory. Like Democrats, they can talk about innocent victims (of harmful Democratic policies) and about fairness (particularly the unfairness of taking tax money from hardworking and prudent people to support cheaters, slackers, and irresponsible fools). But Republicans since Nixon have had a near-monopoly on appeals to loyalty (particularly patriotism and military virtues) and authority (including respect for parents, teachers, elders, and the police, as well as for traditions). And after they embraced Christian conservatives during Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign and became the party of “family values,” Republicans inherited a powerful network of Christian ideas about sanctity and sexuality that allowed them to portray Democrats as the party of Sodom and Gomorrah. Set against the rising crime and chaos of the 1960s and 1970s, this five-foundation morality had wide appeal, even to many Democrats (the so-called Reagan Democrats). The moral vision offered by the Democrats since the 1960s, in contrast, seemed narrow, too focused on helping victims and fighting for the rights of the oppressed. The Democrats offered just sugar (Care) and salt (Fairness as equality), whereas Republican morality appealed to all five taste receptors.

That was the story I told to the Charlottesville Democrats. I didn’t blame the Republicans for trickery. I blamed the Democrats for psychological naiveté. I expected an angry reaction, but after two consecutive losses to George W. Bush, Democrats were so hungry for an explanation that the audience seemed willing to consider mine. Back then, however, my explanation was just speculation. I had not yet collected any data to support my claim that conservatives responded to a broader set of moral tastes than did liberals.2

MEASURING MORALS

Fortunately, a graduate student arrived at UVA that year who made an honest man out of me. If Match.com had offered a way to pair up advisors and grad students, I couldn’t have found a better partner than Jesse Graham. He had graduated from the University of Chicago (scholarly breadth), earned a master’s degree at the Harvard Divinity School (an appreciation of religion), and then spent a year teaching English in Japan (cross-cultural experience). For Jesse’s first-year research project, he created a questionnaire to measure people’s scores on the five moral foundations.

We worked with my colleague Brian Nosek to create the first version of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ), which began with these instructions: “When you decide whether something is right or wrong, to what extent are the following considerations relevant to your thinking?” We then explained the response scale, from 0 (“not at all relevant—this has nothing to do with my judgments of right and wrong”) to 5 (“extremely relevant—this is one of the most important factors when I judge right and wrong”). We then listed fifteen statements—three for each of the five foundations—such as “whether or not someone was cruel” (for the Care foundation) or “whether or not someone showed a lack of respect for authority” (for the Authority foundation).

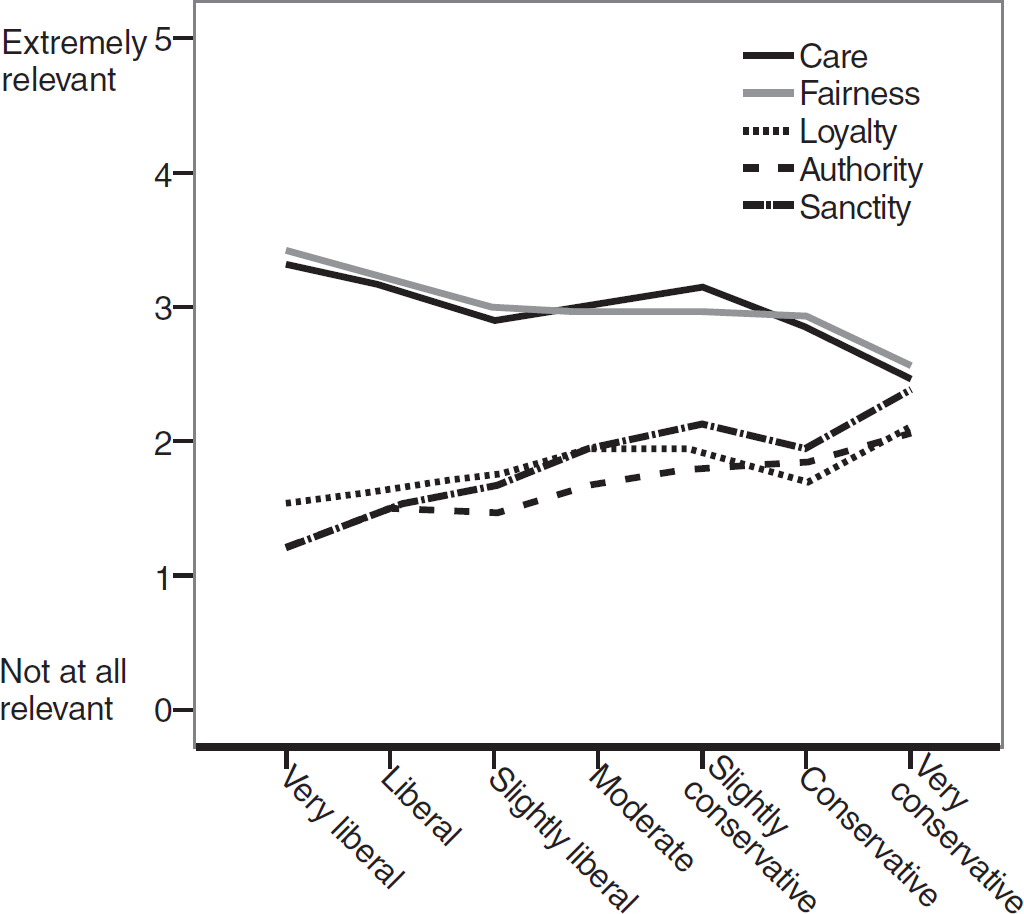

Brian was the director of ProjectImplicit.org, one of the largest research sites on the Internet, so we were able to recruit 1,600 subjects to fill out the MFQ within a week. When Jesse graphed the data, he found exactly the differences we had predicted. I’ve reprinted Jesse’s graph in figure 1, which shows responses from people who said they were “very liberal” on the far left, and then moves along the political spectrum through moderates (in the middle) to people who self-identified as “very conservative” (on the far right).3

As you can see, the lines for Care and Fairness (the two top lines) are moderately high across the board. Everyone—left, right, and center—says that concerns about compassion, cruelty, fairness, and injustice are relevant to their judgments about right and wrong. Yet still, the lines slope downward. Liberals say that these issues are a bit more relevant to morality than do conservatives.

But when we look at the Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity foundations, the story is quite different. Liberals largely reject these considerations. They show such a large gap between these foundations versus the Care and Fairness foundations that we might say, as shorthand, that liberals have a two-foundation morality.4 As we move to the right, however, the lines slope upward. By the time we reach people who are “very conservative,” all five lines have converged. We can say, as shorthand, that conservatives have a five-foundation morality. But can it really be true that conservatives care about a broader range of moral values and issues than do liberals? Or did this pattern only arise because of the particular questions that we happened to ask?

FIGURE 1. The first evidence for Moral Foundations Theory. (Adapted with permission from Graham, Haidt, and Nosek 2009, p. 1033; published by the American Psychological Association.)

Over the next year, Jesse, Brian, and I refined the MFQ. We added questions that asked people to rate their agreement with statements we wrote to trigger intuitions related to each foundation. For example, do you agree with this Care item: “One of the worst things a person can do is to hurt a defenseless animal”? How about this Loyalty item: “It is more important to be a team player than to express oneself”? Jesse’s original findings replicated beautifully. We found the same pattern as in figure 1, and we found it in subjects from many countries besides the United States.5

I began to show our graphs whenever I gave lectures about moral psychology. Ravi Iyer, a graduate student at the University of Southern California, heard me speak in the fall of 2006 and emailed me to ask if he could use the MFQ in his research on attitudes about immigration. Ravi was a skilled Web programmer, and he offered to help Jesse and me create a website for our own research. At around the same time, Sena Koleva, a graduate student at the University of California at Irvine, asked me if she could use the MFQ. Sena was studying political psychology with her advisor, Pete Ditto (whose work on “motivated reasoning” I described in chapter 4). I said yes to both requests.

Every January, social psychologists from all over the world flock to a single conference to learn about each other’s work—and to gossip, network, and drink. In 2007, that conference was held in Memphis, Tennessee. Ravi, Sena, Pete, Jesse, and I met late one evening at the hotel bar, to share our findings and get to know one another.

All five of us were politically liberal, yet we shared the same concern about the way our liberal field approached political psychology. The goal of so much research was to explain what was wrong with conservatives. (Why don’t conservatives embrace equality, diversity, and change, like normal people?) Just that day, in a session on political psychology, several of the speakers had made jokes about conservatives, or about the cognitive limitations of President Bush. All five of us felt this was wrong, not just morally (because it creates a hostile climate for the few conservatives who might have been in the audience) but also scientifically (because it revealed a motivation to reach certain conclusions, and we all knew how easy it is for people to reach their desired conclusions).6 The five of us also shared a deep concern about the polarization and incivility of American political life, and we wanted to use moral psychology to help political partisans understand and respect each other.

We talked about several ideas for future studies, and for each one Ravi said, “You know, we could do that online.” He proposed that we create a website where people could register when they first visit, and then take part in dozens of studies on moral and political psychology. We could then link all of their responses together and develop a comprehensive moral profile for each (anonymous) visitor. In return, we’d give visitors detailed feedback, showing them how they compared to others. If we made the feedback interesting enough, people would tell their friends about the site.

Over the next few months, Ravi designed the website—www.YourMorals.org—and the five of us worked together to improve it. On May 9 we got approval from the UVA human subjects committee to conduct the research, and the site went live the next day. Within a few weeks we were getting ten or more visitors a day. Then, in August, the science writer Nicholas Wade interviewed me for an article in the New York Times on the roots of morality.7 He included the name of our website. The article ran on September 18, and by the end of that week, 26,000 new visitors had completed one or more of our surveys.

Figure 2 shows our data on the MFQ as it stood in 2011, with more than 130,000 subjects. We’ve made many improvements since Jesse’s first simple survey, but we always find the same basic pattern that he found in 2006. The lines for Care and Fairness slant downward; the lines for Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity slant upward. Liberals value Care and Fairness far more than the other three foundations; conservatives endorse all five foundations more or less equally.8

FIGURE 2. Scores on the MFQ, from 132,000 subjects, in 2011. Data from YourMorals.org.

We’ve found this basic difference no matter how we ask the questions. For example, in one study we asked people which traits would make them more or less likely to choose a particular breed of dog as a pet. On which side of the political spectrum do you suppose these traits would be most appealing?

-

The breed is extremely gentle.

-

The breed is very independent-minded and relates to its owner as a friend and equal.

-

The breed is extremely loyal to its home and family and it doesn’t warm up quickly to strangers.

-

The breed is very obedient and is easily trained to take orders.

-

The breed is very clean and, like a cat, takes great care with its personal hygiene.

We found that people want dogs that fit their own moral matrices. Liberals want dogs that are gentle (i.e., that fit with the values of the Care foundation) and relate to their owners as equals (Fairness as equality). Conservatives, on the other hand, want dogs that are loyal (Loyalty) and obedient (Authority). (The Sanctity item showed no partisan tilt; both sides prefer clean dogs.)

The converging pattern shown in figure 2 is not just something we find in Internet surveys. We found it in church too. Jesse obtained the text of dozens of sermons that were delivered in Unitarian (liberal) churches, and dozens more that were delivered in Southern Baptist (conservative) churches. Before reading the sermons, Jesse identified hundreds of words that were conceptually related to each foundation (for example, peace, care, and compassion on the positive side of Care, and suffer, cruel, and brutal on the negative side; obey, duty, and honor on the positive side of Authority, and defy, disrespect, and rebel on the negative side). Jesse then used a computer program called LIWC to count the number of times that each word was used in the two sets of texts.9 This simple-minded method confirmed our findings from the MFQ: Unitarian preachers made greater use of Care and Fairness words, while Baptist preachers made greater use of Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity words.10

We find this pattern in brain waves too. We teamed up with Jamie Morris, a social neuroscientist at UVA, to present liberal and conservative students with sixty sentences that came in two versions. One version endorsed an idea consistent with a particular foundation, and the other version rejected the idea. For example, half of our subjects read “Total equality in the workplace is necessary.” The other half read “Total equality in the workplace is unrealistic.” Subjects wore a special cap to measure their brain waves as the words in each sentence were flashed up on a screen, one word at a time. We later looked at the encephalogram (EEG) to determine whose brains showed evidence of surprise or shock at the moment that the key word was presented (e.g., necessary versus unrealistic).11

Liberal brains showed more surprise, compared to conservative brains, in response to sentences that rejected Care and Fairness concerns. They also showed more surprise in response to sentences that endorsed Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity concerns (for example, “In the teenage years, parental advice should be heeded” versus “…should be questioned”). In other words, when people choose the labels “liberal” or “conservative,” they are not just choosing to endorse different values on questionnaires. Within the first half second after hearing a statement, partisan brains are already reacting differently. These initial flashes of neural activity are the elephant, leaning slightly, which then causes the rider to reason differently, search for different kinds of evidence, and reach different conclusions. Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.

WHAT MAKES PEOPLE VOTE REPUBLICAN?

When Barack Obama clinched the Democratic nomination for the presidential race in 2008, I was thrilled. At long last, it seemed, the Democrats had chosen a candidate with a broader moral palate, someone able to speak about all five foundations. In his book The Audacity of Hope, Obama showed himself to be a liberal who understood conservative arguments about the need for order and the value of tradition. When he gave a speech on Father’s Day at a black church, he praised marriage and the traditional two-parent family, and he called on black men to take more responsibility for their children.12 When he gave a speech on patriotism, he criticized the liberal counterculture of the 1960s for burning American flags and for failing to honor veterans returning from Vietnam.13

But as the summer of 2008 went on, I began to worry. His speech to a major civil rights organization was all about social justice and corporate greed.14 It used only the Care and Fairness foundations, and fairness often meant equality of outcomes. In his famous speech in Berlin, he introduced himself as “a fellow citizen of the world” and he spoke of “global citizenship.”15 He had created a controversy earlier in the summer by refusing to wear an American flag pin on the lapel of his jacket, as American politicians typically do. The controversy seemed absurd to liberals, but the Berlin speech reinforced the emerging conservative narrative that Obama was a liberal universalist, someone who could not be trusted to put the interests of his nation above the interests of the rest of the world. His opponent, John McCain, took advantage of Obama’s failure to build on the Loyalty foundation with his own campaign motto: “Country First.”

Anxious that Obama would go the way of Gore and Kerry, I wrote an essay applying Moral Foundations Theory to the presidential race. I wanted to show Democrats how they could talk about policy issues in ways that would activate more than two foundations. John Brockman, who runs an online scientific salon at Edge.org, invited me to publish the essay at Edge,16 as long as I stripped out most of the advice and focused on the moral psychology.

I titled the essay “What Makes People Vote Republican?” I began by summarizing the standard explanations that psychologists had offered for decades: Conservatives are conservative because they were raised by overly strict parents, or because they are inordinately afraid of change, novelty, and complexity, or because they suffer from existential fears and therefore cling to a simple worldview with no shades of gray.17 These approaches all had one feature in common: they used psychology to explain away conservatism. They made it unnecessary for liberals to take conservative ideas seriously because these ideas are caused by bad childhoods or ugly personality traits. I suggested a very different approach: start by assuming that conservatives are just as sincere as liberals, and then use Moral Foundations Theory to understand the moral matrices of both sides.

The key idea in the essay was that there are two radically different approaches to the challenge of creating a society in which unrelated people can live together peacefully. One approach was exemplified by John Stuart Mill, the other by the great French sociologist Emile Durkheim. I described Mill’s vision like this:

First, imagine society as a social contract invented for our mutual benefit. All individuals are equal, and all should be left as free as possible to move, develop talents, and form relationships as they please. The patron saint of a contractual society is John Stuart Mill, who wrote (in On Liberty) that “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.” Mill’s vision appeals to many liberals and libertarians; a Millian society at its best would be a peaceful, open, and creative place where diverse individuals respect each other’s rights and band together voluntarily (as in Obama’s calls for “unity”) to help those in need or to change the laws for the common good.

I showed how this vision of society rests exclusively on the Care and Fairness foundations. If you assume that everyone relies on those two foundations, you can assume that people will be bothered by cruelty and injustice and will be motivated to respect each other’s rights. I then contrasted Mill’s vision with Durkheim’s:

Now imagine society not as an agreement among individuals but as something that emerged organically over time as people found ways of living together, binding themselves to each other, suppressing each other’s selfishness, and punishing the deviants and free riders who eternally threaten to undermine cooperative groups. The basic social unit is not the individual, it is the hierarchically structured family, which serves as a model for other institutions. Individuals in such societies are born into strong and constraining relationships that profoundly limit their autonomy. The patron saint of this more binding moral system is the sociologist Emile Durkheim, who warned of the dangers of anomie (normlessness) and wrote, in 1897, that “man cannot become attached to higher aims and submit to a rule if he sees nothing above him to which he belongs. To free himself from all social pressure is to abandon himself and demoralize him.” A Durkheimian society at its best would be a stable network composed of many nested and overlapping groups that socialize, reshape, and care for individuals who, if left to their own devices, would pursue shallow, carnal, and selfish pleasures. A Durkheimian society would value self-control over self-expression, duty over rights, and loyalty to one’s groups over concerns for out-groups.

I showed that a Durkheimian society cannot be supported by the Care and Fairness foundations alone.18 You have to build on the Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity foundations as well. I then showed how the American left fails to understand social conservatives and the religious right because it cannot see a Durkheimian world as anything other than a moral abomination.19 A Durkheimian world is usually hierarchical, punitive, and religious. It places limits on people’s autonomy and it endorses traditions, often including traditional gender roles. For liberals, such a vision must be combated, not respected.

If your moral matrix rests entirely on the Care and Fairness foundations, then it’s hard to hear the sacred overtones in America’s unofficial motto: E pluribus unum (from many, one). By “sacred” I mean the concept at the heart of the Sanctity foundation, which you can see operating in nearly all religions. It’s the ability to endow ideas, objects, and events with infinite value, particularly those ideas, objects, and events that bind a group together into a single entity. It's the ability to make something holy, and then feel anger when someone desecrates what you and your group revere. The process of converting pluribus (diverse people) into unum (a nation) is a miracle that occurs in every successful nation on Earth.20 Nations decline or divide when they stop performing this miracle.

In the 1960s, the Democrats became the party of pluribus. Democrats generally celebrate diversity, support immigration without assimilation, oppose making English the national language, don’t like to wear flag pins, and refer to themselves as citizens of the world. Is it any wonder that they have done so poorly in presidential elections since 1968?21 The president is the high priest of what sociologist Robert Bellah calls the “American civil religion.”22 The president must invoke the name of God (though not Jesus), glorify America’s heroes and history, quote its sacred texts (the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution), and perform the transubstantiation of pluribus into unum. Would Catholics ever choose a priest who refuses to speak Latin, or who considers himself a devotee of all gods?

In the remainder of the essay I advised Democrats to stop dismissing conservatism as a pathology and start thinking about morality beyond care and fairness. I urged them to close the sacredness gap between the two parties by making greater use of the Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity foundations, not just in their “messaging,” but in how they think about public policy and the best interests of the nation.23

WHAT I HAD MISSED

The essay provoked strong reactions from readers, which they sometimes shared with me by email. On the left, many readers stayed locked inside their Care-based moral matrices and refused to believe that conservatism was an alternative moral vision. For example, one reader said that he agreed with my diagnosis but thought that narcissism was an additional factor that I had not mentioned: “Lack of compassion fits them [Republicans], and narcissists are also lacking this important human trait.” He thought it was “sad” that Republican narcissism would prevent them from understanding my perspective on their “illness.”

Reactions from the right were generally more positive. Many readers with military or religious backgrounds found my portrayal of their morality accurate and useful, as in this email:

I recently retired from the U.S. Coast Guard after 22 years of service….After I retired, I took a job with [a government science agency]. The [new office’s] culture tends more towards the liberal independent model….What I am finding here is an organization rife with individualism and infighting, at the expense of larger goals. In the military, I was always impressed with the great deeds that could be accomplished by a small number of dedicated people with limited resources. In my new group, I am impressed when we can accomplish anything at all.24

I also received quite a few angry responses, particularly from economic conservatives who believed I had misunderstood their morality. One such reader sent me an email with the subject line “Head up ass,” which he explained in this way:

I vote republican because I’m against other people (authority figures) taking my money (that I work hard for) and giving it to a non-producing, welfare collecting, single mother, crack baby producing future democrat. Simple…You’re an over educated “philosopher” with soft hands who gets paid to ask stupid questions and come up with “reasonable” answers….Go drop some acid and read some Jung.

Another angry reader posted to a blog discussion his own list of the “top fifteen reasons that people vote Democrat.” His number one reason was “Low IQ,” but the rest of his list revealed a lot about his moral matrix and its central value. It included the following:

-

Laziness.

-

You want something for nothing.

-

You need someone to blame for your problems.

-

You’re afraid of personal responsibility or simply not willing to accept any.

-

You despise people who work hard for their money, live their own lives, and don’t rely on the government for help cradle to grave.

-

You’ve had 5 kids from 3 different men and you need the welfare check.

These emails were overflowing with moral content, yet I had a hard time categorizing that content using Moral Foundations Theory. Much of it was related to fairness, but this kind of fairness had nothing to do with equality. It was the fairness of the Protestant work ethic and the Hindu law of karma: People should reap what they sow. People who work hard should get to keep the fruits of their labor. People who are lazy and irresponsible should suffer the consequences.

This email and other responses from economic conservatives made me realize that I and my colleagues at YourMorals.org had done a poor job of capturing conservative notions of fairness, which focused on proportionality, not equality. People should get what they deserve, based on what they have done. We had assumed that equality and proportionality were both part of the Fairness foundation, but the questions we used to measure this foundation were mostly about equality and equal rights. We therefore found that liberals cared more about fairness, and that’s what had made these economic conservatives so angry at me. They believed that liberals don’t give a damn about fairness (as proportionality).

Are proportionality and equality two different expressions of the same underlying cognitive module, as we had been assuming? Are they both related to reciprocal altruism, as the biologist Robert Trivers had described it? It’s easy to explain why people care about proportionality and are so keen to catch cheaters. That follows directly from Trivers’s analysis of how we gain by exchanging favors with reliable partners. But what about equality? Are liberal concerns about political and economic equality really related to reciprocal altruism? Is the passionate anger people feel toward bullies and oppressors the same as the anger they feel toward cheaters?

I looked into what was known about the egalitarianism of hunter-gatherers, and found a strong argument for splitting apart these two kinds of fairness. The desire for equality seems to be more closely related to the psychology of liberty and oppression than to the psychology of reciprocity and exchange. After talking about these issues with my colleagues at YourMorals.org, and after we ran some new studies on various kinds of fairness and liberty, we added a provisional sixth foundation—Liberty/oppression.25 We also decided to revise our thinking about fairness to place more emphasis on proportionality. Let me explain.

THE LIBERTY/OPPRESSION FOUNDATION

Humans are, like our primate ancestors, innately equipped to live in dominance hierarchies that can be quite brutal. But if that’s true, then how come nomadic hunter-gatherers are always egalitarian? There’s no hierarchy (at least among the adult males), there’s no chief, and the norms of the group actively encourage sharing resources, particularly meat.26 The archaeological evidence supports this view, indicating that our ancestors lived for hundreds of thousands of years in egalitarian bands of mobile hunter-gatherers.27 Hierarchy only becomes widespread around the time that groups take up agriculture or domesticate animals and become more sedentary. These changes create much more private property and much larger group sizes. They also put an end to equality. The best land and a share of everything people produce typically get dominated by a chief, leader, or elite class (who take some of their wealth with them to the grave for easy interpretation by later archaeologists). So were our minds “structured in advance of experience” for hierarchy or for equality?

For hierarchy, according to the anthropologist Christopher Boehm. Boehm studied tribal cultures early in his career, but had also studied chimpanzees with Jane Goodall. He recognized the extraordinary similarities in the ways that humans and chimpanzees display dominance and submission. In his book Hierarchy in the Forest, Boehm concluded that human beings are innately hierarchical, but that at some point during the last million years our ancestors underwent a “political transition” that allowed them to live as egalitarians by banding together to rein in, punish, or kill any would-be alpha males who tried to dominate the group.

Alpha male chimps are not truly leaders of their groups. They perform some public services, such as mediating conflicts.28 But most of the time, they are better described as bullies who take what they want. Yet even among chimpanzees, it sometimes happens that subordinates gang up to take down alphas, occasionally going as far as to kill them.29 Alpha male chimps must therefore know their limits and have enough political skill to cultivate a few allies and stave off rebellion.

Imagine early hominid life as a tense balance of power between the alpha (and an ally or two) and the larger set of males who are shut out of power. Then arm everyone with spears. The balance of power is likely to shift when physical strength no longer decides the outcome of every fight. That’s essentially what happened, Boehm suggests, as our ancestors developed better weapons for hunting and butchering beginning around five hundred thousand years ago, when the archaeological record begins to show a flowering of tool and weapon types.30 Once early humans had developed spears, anyone could kill a bullying alpha male. And if you add the ability to communicate with language, and note that every human society uses language to gossip about moral violations,31 then it becomes easy to see how early humans developed the ability to unite in order to shame, ostracize, or kill anyone whose behavior threatened or simply annoyed the rest of the group.

Boehm’s claim is that at some point during the last half-million years, well after the advent of language, our ancestors created the first true moral communities.32 In these communities, people used gossip to identify behavior they didn’t like, particularly the aggressive, dominating behaviors of would-be alpha males. On the rare occasions when gossip wasn’t enough to bring violators into line, the community had the ability to use weapons to take them down. Boehm quotes a dramatic account of such a case among the !Kung people of the Kalahari Desert:

A man named Twi had killed three other people, when the community, in a rare move of unanimity, ambushed and fatally wounded him in full daylight. As he lay dying, all of the men fired at him with poisoned arrows until, in the words of one informant, “he looked like a porcupine.” Then, after he was dead, all the women as well as the men approached his body and stabbed him with spears, symbolically sharing the responsibility for his death.33

It’s not that human nature suddenly changed and became egalitarian; men still tried to dominate others when they could get away with it. Rather, people armed with weapons and gossip created what Boehm calls “reverse dominance hierarchies” in which the rank and file band together to dominate and restrain would-be alpha males. (It’s uncannily similar to Marx’s dream of the “dictatorship of the proletariat.”)34 The result is a fragile state of political egalitarianism achieved by cooperation among creatures who are innately predisposed to hierarchical arrangements. It’s a great example of how “innate” refers to the first draft of the mind. The final edition can look quite different, so it’s a mistake to look at today’s hunter-gatherers and say, “See, that’s what human nature really looks like!”

For groups that made this political transition to egalitarianism, there was a quantum leap in the development of moral matrices. People now lived in much denser webs of norms, informal sanctions, and occasionally violent punishments. Those who could navigate this new world skillfully and maintain good reputations were rewarded by gaining the trust, cooperation, and political support of others. Those who could not respect group norms, or who acted like bullies, were removed from the gene pool by being shunned, expelled, or killed. Genes and cultural practices (such as the collective killing of deviants) coevolved.

The end result, says Boehm, was a process sometimes called “self-domestication.” Just as animal breeders can create tamer, gentler creatures by selectively breeding for those traits, our ancestors began to selectively breed themselves (unintentionally) for the ability to construct shared moral matrices and then live cooperatively within them.

The Liberty/oppression foundation, I propose, evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of living in small groups with individuals who would, if given the chance, dominate, bully, and constrain others. The original triggers therefore include signs of attempted domination. Anything that suggests the aggressive, controlling behavior of an alpha male (or female) can trigger this form of righteous anger, which is sometimes called reactance. (That’s the feeling you get when an authority says you can’t do something and you feel yourself wanting to do it even more strongly.)35 But people don’t suffer oppression in private; the rise of a would-be dominator triggers a motivation to unite as equals with other oppressed individuals to resist, restrain, and in extreme cases kill the oppressor. Individuals who failed to detect signs of domination and respond to them with righteous and group-unifying anger faced the prospect of reduced access to food, mates, and all the other things that make individuals (and their genes) successful in the Darwinian sense.36

The Liberty foundation obviously operates in tension with the Authority foundation. We all recognize some kinds of authority as legitimate in some contexts, but we are also wary of those who claim to be leaders unless they have first earned our trust. We’re vigilant for signs that they’ve crossed the line into self-aggrandizement and tyranny.37

The Liberty foundation supports the moral matrix of revolutionaries and “freedom fighters” everywhere. The American Declaration of Independence is a long enumeration of “repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of absolute Tyranny over these states.” The document begins with the claim that “all men are created equal” and ends with a stirring pledge of unity: “We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” The French revolutionaries, similarly, had to call for fraternité and égalité if they were going to entice commoners to join them in their regicidal quest for liberté.

The flag of Virginia celebrates assassination (see figure 3). It’s a bizarre flag, unless you understand the Liberty/oppression foundation. The flag shows virtue (embodied as a woman) standing on the chest of a dead king, with the motto Sic semper tyrannis (“Thus always to tyrants”). That was the rallying cry said to have been shouted by Marcus Brutus as he and his co-conspirators murdered Julius Caesar for acting like an alpha male. John Wilkes Booth shouted it from center stage at Ford’s Theatre moments after shooting Abraham Lincoln (whom Southerners perceived to be a tyrant who prevented them from declaring independence).

FIGURE 3. The flag of Virginia, illustrating the Liberty/oppression foundation.

Murder often seems virtuous to revolutionaries. It just somehow feels like the right thing to do, and these feelings seem far removed from Trivers’s reciprocal altruism and tit for tat. This is not fairness. This is Boehm’s political transition and reverse dominance.

If the original triggers of this foundation include bullies and tyrants, the current triggers include almost anything that is perceived as imposing illegitimate restraints on one’s liberty, including government (from the perspective of the American right). In 1993, when Timothy McVeigh was arrested a few hours after he blew up a federal office building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people, he was wearing a T-shirt that said Sic semper tyrannis. Less ominously, the populist anger of the Tea Party relies on this foundation, as shown in their unofficial flag, which says “Don’t tread on me”.

But despite these manifestations on the right, the urge to band together to oppose oppression and replace it with political equality seems to be at least as prevalent on the left. For example, one liberal reader of my “Republicans” essay stated Boehm’s thesis precisely:

The enemy of society to a Liberal is someone who abuses their power (Authority) and still demands, and in some cases forces, others to “respect” them anyway….A Liberal authority is someone or something that earns society’s respect through making things happen that unify society and suppress its enemy. [Emphasis added.]38

It’s not just the accumulation and abuse of political power that activates the anger of the Liberty/oppression foundation; the current triggers can expand to encompass the accumulation of wealth, which helps to explain the pervasive dislike of capitalism on the far left. For example, one liberal reader explained to me, “Capitalism is, in the end, predatory—a moral society will be socialist, i.e., people will help each other.”

You can hear the heavy reliance on the Liberty/oppression foundation whenever people talk about social justice. The owners of a progressive coffee shop and “cultural collective” in New Paltz, New York, used this foundation, along with the Care foundation, to guide their decorating choices, as you can see in figure 4.

The hatred of oppression is found on both sides of the political spectrum. The difference seems to be that for liberals—who are more universalistic and who rely more heavily upon the Care/harm foundation—the Liberty/oppression foundation is employed in the service of underdogs, victims, and powerless groups everywhere. It leads liberals (but not others) to sacralize equality, which is then pursued by fighting for civil rights and human rights. Liberals sometimes go beyond equality of rights to pursue equality of outcomes, which cannot be obtained in a capitalist system. This may be why the left usually favors higher taxes on the rich, high levels of services provided to the poor, and sometimes a guaranteed minimum income for everyone.

FIGURE 4. Liberal liberty: Interior of a coffee shop in New Paltz, New York. The sign on the left says, “No one is free when others are oppressed.” The flag on the right shows corporate logos replacing stars on the American flag. The sign in the middle says, “How to end violence against women and children.”

Conservatives, in contrast, are more parochial—concerned about their groups, rather than all of humanity. For them, the Liberty/oppression foundation and the hatred of tyranny supports many of the tenets of economic conservatism: don’t tread on me (with your liberal nanny state and its high taxes), don’t tread on my business (with your oppressive regulations), and don’t tread on my nation (with your United Nations and your sovereignty-reducing international treaties).

American conservatives, therefore, sacralize the word liberty, not the word equality. This unites them politically with libertarians. The evangelical preacher Jerry Falwell chose the name Liberty University when he founded his ultraconservative school in 1971. Figure 5 shows the car of a Liberty student. Liberty students are generally pro-authority. They favor traditional patriarchal families. But they oppose domination and control by a secular government, particularly a liberal government that will (they fear) use its power to redistribute wealth (as “comrade Obama” was thought likely to do).

FIGURE 5. Conservative liberty: car at a dormitory at Liberty University, Lynchburg, Virginia. The lower sticker says, “Libertarian: More Freedom, Less Government.”

FAIRNESS AS PROPORTIONALITY

The Tea Party emerged as if from nowhere in the early months of the Obama presidency to reshape the American political landscape and realign the American culture war. The movement began in earnest on February 19, 2009, when Rick Santelli, a correspondent for a business news network, launched a tirade against a new $75 billion program to help homeowners who had borrowed more money than they could now repay. Santelli, who was broadcasting live from the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, said, “The government is promoting bad behavior.” He then urged President Obama to put up a website to hold a national referendum

to see if we really want to subsidize the losers’ mortgages, or would we like to at least buy cars and buy houses in foreclosure and give them to people that might have a chance to actually prosper down the road and reward people that could carry the water instead of drink the water. [At this point, cheers erupted behind him]…This is America. How many of you people want to pay for your neighbors’ mortgage that has an extra bathroom and can’t pay their bills? President Obama, are you listening? [Emphasis added.]

Santelli then announced that he was thinking of hosting a “Chicago Tea Party” in July.39 Commentators on the left mocked Santelli, and many thought he was endorsing an ugly dog-eat-dog morality in which the “losers” (many of whom had been tricked by unscrupulous lenders) should be left to die. But in fact Santelli was arguing for the law of karma.

It took me a long time to understand fairness because, like many people who study morality, I had thought of fairness as a form of enlightened self-interest, based on Trivers’s theory of reciprocal altruism. Genes for fairness evolved, said Trivers, because people who had those genes outcompeted people who didn’t. We don’t have to abandon the idea of Homo economicus; we just have to give him emotional reactions that compel him to play tit for tat.

In the last ten years, however, evolutionary theorists have realized that reciprocal altruism is not so easy to find among nonhuman species.40 The widely reported claim that vampire bats share blood meals with other bats who had previously shared with them turned out to be a case of kin selection (relatives sharing blood), not reciprocal altruism.41 The evidence for reciprocity in chimpanzees and capuchins is better but still ambiguous.42 It seems to take more than just a high level of social intelligence to get reciprocal altruism going. It takes the sort of gossiping, punitive, moralistic community that emerged only when language and weaponry made it possible for early humans to take down bullies and then keep them down with a shared moral matrix.43

Reciprocal altruism also fails to explain why people cooperate in group activities. Reciprocity works great for pairs of people, who can play tit for tat, but in groups it’s usually not in an individual’s self-interest to be the enforcer—the one who punishes slackers. Yet punish we do, and our propensity to punish turns out to be one of the keys to large-scale cooperation.44 In one classic experiment, economists Ernst Fehr and Simon Gächter asked Swiss students to play twelve rounds of a “public goods” game.45 The game goes like this: You and your three partners each get 20 tokens on each round (each worth about ten American cents). You can keep your tokens, or you can “invest” some or all of them in the group’s common pot. At the end of each round, the experimenters multiply the tokens in the pot by 1.6 and then divide the pot among the four players, so if everyone puts in all 20 tokens, the pot grows from 80 to 128, and everyone gets to keep 32 tokens (which get turned into real money at the end of the experiment). But each individual does best by holding back: If you put in nothing while your partners put in 20 each, you get to keep your 20 tokens plus a quarter of the pot provided by your trusting partners (a quarter of 96), so you end the round with 44 tokens.

Each person sat at a computer in a cubicle, so nobody knew who their partners were on any particular round, although they saw a feedback screen after each round revealing exactly how much each of the four players had contributed. Also, after each round, Fehr and Gächter scrambled the groups so that each person played with three new partners—there was no chance to develop norms of trust, and no chance for anyone to use tit for tat (by holding back on the next round if anyone “cheated” on the current round).

Under these circumstances, the right choice for Homo economicus is clear: contribute nothing, ever. Yet in fact the students did contribute to the common pot—about ten tokens on the first round. As the game went on, however, people felt burned by the low contributions of some of their partners, and contributions dropped steadily, down to about six tokens on the sixth round.

That pattern—partial but declining cooperation—has been reported before. But here’s the reason this is such a brilliant study: After the sixth round, the experimenters told subjects that there was a new rule: After learning how much each of your partners contributed on each round, you now would have the option of paying, with your own tokens, to punish specific other players. Every token you paid to punish would take three tokens away from the player you punished.

For Homo economicus, the right course of action is once again perfectly clear: never pay to punish, because you will never again play with those three partners, so there is no chance to benefit from reciprocity or from gaining a tough reputation. Yet remarkably, 84 percent of subjects paid to punish, at least once. And even more remarkably, cooperation skyrocketed on the very first round where punishment was allowed, and it kept on climbing. By the twelfth round, the average contribution was fifteen tokens.46 Punishing bad behavior promotes virtue and benefits the group. When the threat of punishment is removed, people behave selfishly.

Why did most players pay to punish? In part, because it felt good to do so.47 We hate to see people take without giving. We want to see cheaters and slackers “get what’s coming to them.” We want the law of karma to run its course, and we’re willing to help enforce it.

When people trade favors, both parties end up equal, more or less, and so it is easy to think (as I had) that reciprocal altruism was the source of moral intuitions about equality. But egalitarianism seems to be rooted more in the hatred of domination than in the love of equality per se.48 The feeling of being dominated or oppressed by a bully is very different from the feeling of being cheated in an exchange of goods or favors.

Once my team at YourMorals.org had identified Liberty/oppression as a (provisionally) separate sixth foundation, we began to notice that in our data, concerns about political equality were related to a dislike of oppression and a concern for victims, not a desire for reciprocity.49 And if the love of political equality rests on the Liberty/oppression and Care/harm foundations rather than the Fairness/cheating foundation, then the Fairness foundation no longer has a split personality; it’s no longer about equality and proportionality. It is primarily about proportionality.

When people work together on a task, they generally want to see the hardest workers get the largest gains.50 People often want equality of outcomes, but that is because it is so often the case that people’s inputs were equal. When people divide up money, or any other kind of reward, equality is just a special case of the broader principle of proportionality. When a few members of a group contributed far more than the others—or, even more powerfully, when a few contributed nothing—most adults do not want to see the benefits distributed equally.51

We can therefore refine the description of the Fairness foundation from its original formulation in Moral Foundations Theory. It’s still a set of cognitive modules that evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of reaping the rewards of cooperation without getting exploited by free riders.52 But now that we’ve begun to talk about moral communities within which cooperation is maintained by gossip and punishment, we can look beyond individuals trying to choose partners. We can look more closely at people’s strong desires to protect their communities from cheaters, slackers, and free riders, who, if allowed to continue their ways without harassment, would cause others to stop cooperating, which would cause society to unravel. The Fairness foundation supports righteous anger when anyone cheats you directly (for example, a car dealer who knowingly sells you a lemon). But it also supports a more generalized concern with cheaters, leeches, and anyone else who “drinks the water” rather than carries it for the group.

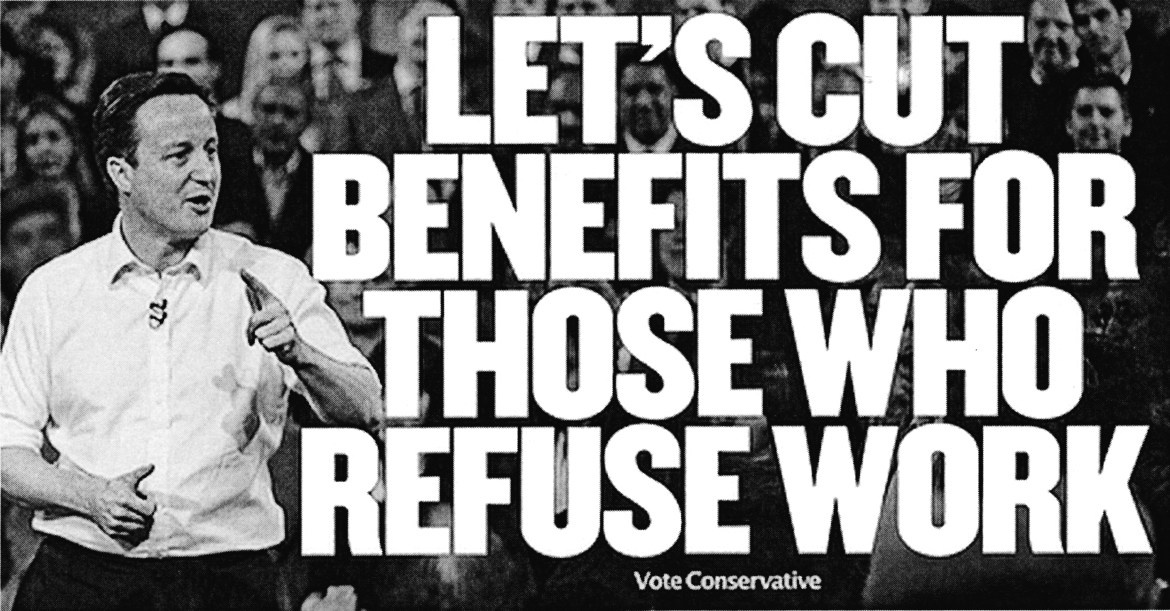

The current triggers of the Fairness foundation vary depending on a group’s size and on many historical and economic circumstances. In a large industrial society with a social safety net, the current triggers are likely to include people who rely upon the safety net for more than an occasional lifesaving bounce. Concerns about the abuse of the safety net explain the angry emails I received from economic conservatives, such as the man who did not want his tax dollars going to “a non-producing, welfare collecting, single mother, crack baby producing future democrat.” It explains the conservative’s list of reasons why people vote Democratic, such as “laziness” and “You despise people who work hard for their money, live their own lives, and don’t rely on the government for help cradle to grave.” It explains Santelli’s rant about bailing out homeowners, many of whom had lied on their mortgage applications to qualify for large loans they did not deserve. And it explains the campaign poster in figure 6, from David Cameron’s Conservative Party in the United Kingdom.

THREE VERSUS SIX

To put this all together: Moral Foundations Theory says that there are (at least) six psychological systems that comprise the universal foundations of the world’s many moral matrices.53 The various moralities found on the political left tend to rest most strongly on the Care/harm and Liberty/oppression foundations. These two foundations support ideals of social justice, which emphasize compassion for the poor and a struggle for political equality among the subgroups that comprise society. Social justice movements emphasize solidarity—they call for people to come together to fight the oppression of bullying, domineering elites. (This is why there is no separate equality foundation. People don’t crave equality for its own sake;54 they fight for equality when they perceive that they are being bullied or dominated, as during the American and French revolutions, and the cultural revolutions of the 1960s.)55

FIGURE 6. Fairness as proportionality. The right is usually more concerned about catching and punishing free riders than is the left. (Campaign poster for the Conservative Party in the UK parliamentary elections of 2010.)

Everyone—left, right, and center—cares about Care/harm, but liberals care more. Across many scales, surveys, and political controversies, liberals turn out to be more disturbed by signs of violence and suffering, compared to conservatives and especially to libertarians.56

Everyone—left, right, and center—cares about Liberty/oppression, but each political faction cares in a different way. In the contemporary United States, liberals are most concerned about the rights of certain vulnerable groups (e.g., racial minorities, children, animals), and they look to government to defend the weak against oppression by the strong. Conservatives, in contrast, hold more traditional ideas of liberty as the right to be left alone, and they often resent liberal programs that use government to infringe on their liberties in order to protect the groups that liberals care most about.57 For example, small business owners overwhelmingly support the Republican Party58 in part because they resent the government telling them how to run their businesses under its banner of protecting workers, minorities, consumers, and the environment. This helps explain why libertarians have sided with the Republican Party in recent decades. Libertarians care about liberty almost to the exclusion of all other concerns,59 and their conception of liberty is the same as that of the Republicans: it is the right to be left alone, free from government interference.

The Fairness/cheating foundation is about proportionality and the law of karma. It is about making sure that people get what they deserve, and do not get things they do not deserve. Everyone—left, right, and center—cares about proportionality; everyone gets angry when people take more than they deserve. But conservatives care more, and they rely on the Fairness foundation more heavily—once fairness is restricted to proportionality. For example, how relevant is it to your morality whether “everyone is pulling their own weight”? Do you agree that “employees who work the hardest should be paid the most”? Liberals don’t reject these items, but they are ambivalent. Conservatives, in contrast, endorse items such as these enthusiastically.60

Liberals may think that they own the concept of karma because of its New Age associations, but a morality based on compassion and concerns about oppression forces you to violate karma (proportionality) in many ways. Conservatives, for example, think it’s self-evident that responses to crime should be based on proportionality, as shown in slogans such as “Do the crime, do the time,” and “Three strikes and you’re out.” Yet liberals are often uncomfortable with the negative side of karma—retribution—as shown on the bumper sticker in figure 7. After all, retribution causes harm, and harm activates the Care/harm foundation. A recent study even found that liberal professors give out a narrower range of grades than do conservative professors. Conservative professors are more willing to reward the best students and punish the worst.61

FIGURE 7. A car in Charlottesville, Virginia, whose owner prefers compassion to proportionality.

The remaining three foundations—Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, and Sanctity/degradation—show the biggest and most consistent partisan differences. Liberals are ambivalent about these foundations at best, whereas social conservatives embrace them. (Libertarians have little use for them, which is why they tend to support liberal positions on social issues such as gay marriage, drug use, and laws to “protect” the American flag.)

I began this piece by telling you our original finding: Liberals have a two-foundation morality, based on the Care and Fairness foundations, whereas conservatives have a five-foundation morality. But on the basis of what we’ve learned in the last few years, I need to revise that statement. Liberals have a three-foundation morality, whereas conservatives use all six. Liberal moral matrices rest on the Care/harm, Fairness/cheating, and Liberty/oppression foundations, although liberals are often willing to trade away fairness (as proportionality) when it conflicts with compassion or with their desire to fight oppression. Conservative morality rests on all six foundations, although conservatives are more willing than liberals to sacrifice Care and let some people get hurt in order to achieve their many other moral objectives.

IN SUM

Moral psychology can help to explain why the Democratic Party has generally had so much difficulty connecting with voters since 1980. Republicans understand the social intuitionist model better than do Democrats. Republicans speak more directly to the elephant. They also have a better grasp of Moral Foundations Theory; they trigger every single taste receptor.

I presented the Durkheimian vision of society, favored by social conservatives, in which the basic social unit is the family, rather than the individual, and in which order, hierarchy, and tradition are highly valued. I contrasted this vision with the liberal Millian vision, which is more open and individualistic. I noted that a Millian society has difficulty binding pluribus into unum. Democrats often pursue policies that promote pluribus at the expense of unum, policies that leave them open to charges of treason, subversion, and sacrilege.

I then described how my colleagues and I revised Moral Foundations Theory to do a better job of explaining intuitions about liberty and fairness:

-

We added the Liberty/oppression foundation, which makes people notice and resent any sign of attempted domination. It triggers an urge to band together to resist or overthrow bullies and tyrants. This foundation supports the egalitarianism and antiauthoritarianism of the left, as well as the don’t-tread-on-me and give-me-liberty antigovernment anger of libertarians and some conservatives.

-

We modified the Fairness foundation to make it focus more strongly on proportionality. The Fairness foundation begins with the psychology of reciprocal altruism, but its duties expanded once humans created gossiping and punitive moral communities. Most people have a deep intuitive concern for the law of karma—they want to see cheaters punished and good citizens rewarded in proportion to their deeds.

With these revisions, Moral Foundations Theory can now explain one of the great puzzles that has preoccupied Democrats in recent years: Why do rural and working-class Americans generally vote Republican when it is the Democratic Party that wants to redistribute money more evenly?

Democrats often say that Republicans have duped these people into voting against their economic self-interest. (That was the thesis of the popular 2004 book What’s the Matter with Kansas?.)62 But from the perspective of Moral Foundations Theory, rural and working-class voters were in fact voting for their moral interests. Their morality is not just about harm, rights, and justice, and they don’t want their nation to devote itself primarily to the care of victims and the pursuit of social justice. Until Democrats understand the Durkheimian vision of society and the difference between a six-foundation morality and a three-foundation morality, they will not understand what makes people vote Republican.