WHY NEUROSCIENCE?

In order to get to know who you are and how you work, you need to metaphorically open the hood and look in at the engine. Freud, who originally wanted to be a neurologist, had to guess what was going on inside because in those days the only way you could study the brain was by hanging around a corpse. A dead brain is not ticking so it doesn’t help. Now we can look in and see how neurons connect to different areas of the brain and watch the electrical and chemical power working throughout to create our thoughts, dreams, hopes, memories, emotions—everything.

We are the result of those connections, those chemical exchanges and of regions communicating with other regions. Some people believe this thinking is too reductionist and say disapprovingly, “Is that all we are?” I feel we should be saying, “Oh my God, I am all this?” Because what we are is so complex and extraordinary; how our brains work makes every other invention and accomplishment look like learning to fold a napkin.

For me, this has been the greatest aha! moment to end all ahas in my life so far. When you begin to grasp how every part of your brain has a function (valuing, thinking, moving, feeling), when you realize it’s the subtle (and not so subtle) differences in our brain biology that make you you and me me, you’ll go aha! too. Then you’ll think, “We absolutely must have the instruction manual for this thing,” and you might even start stalking neuroscientists like I did.

As far as reality checks go, it can’t get better than having a look at the real thing. Each one of our brains looks fairly similar when you crack us open, which to me is so comforting; to know I’m not alone and that we are all brothers under the skin. No light versus dark souls; just a dull pink. The best news of all is that we have reached a point in our development as a species where we can choose how our brains will react to events so that we’re not held entirely captive by our old habits and biases, programming, and mental blind spots. Most people don’t know that this self-regulatory part comes with the package. We’re born with this ability but sadly this information isn’t imparted to the public (perhaps it wouldn’t sell as many books as Seventy-Five Shades of Grey).

When you learn how to use your mind as it can be used, you might even feel that elusive thing called happiness or peace. Yet what is known so far in terms of brain science doesn’t seem to trickle down to the masses, nor does the public seem to want it to trickle. Scientific information about the brain is based on hard evidence from a number of sources, including, most recently, advances in neuroimaging. These provide vivid pictures of the brain’s components and associated functions. Neuroscience as a subject is still on the nursery slopes for the most part, as it is extremely complicated, but scientists have already learned a huge amount about the functions of our brains and the different areas involved when we add numbers, speak, make decisions, remember, hear, see, and stay busy. If you doubt the empirical evidence but you do believe you’ve seen a UFO, please put this book down. It is not for you.

By watching how our thoughts affect the structure of the brain, we’re learning new ways we can consciously reshape our own brains. Self-regulation means we can actually rewire our own brains by moving activity from one region to another, switching on diverse hormones that can stimulate us or calm us down.

In my opinion, learning this ability to self-regulate is the posttherapy zeitgeist. It has become the new holy grail of our time. Evidence of how the brain changes can be seen in brain-imaging scanners, and the results are published in scientific journals. Why isn’t this the hottest news in town? You meet people who insist they know how the world works and themselves by how they feel. It’s like insisting that the world is flat because they feel it is. I know change is painful to us all; old ways are always being replaced by the new. Soothsayers suddenly found themselves out of a job and alchemists were made redundant because people stopped needing their pigs turned into gold, or whatever it was they did. Someday we will laugh our heads off when we remember that a doctor didn’t look inside your brain before he wrote you a prescription. I’m not saying that by simply looking at an image in a scanner we’ll know everything there is to know, because it is true that who we are is also the result of our interactions with our parents, our environment, our learning, and our culture. So to get to the bottom of the twenty-first-century problems we find ourselves facing, we’ll need not only to learn about the basic functional architecture of the human brain but also our personal story and our evolutionary story.

Here, based on scientific evidence, neuroscience, and evolution, are some answers to the questions raised in Part 1. Enjoy.

WHY THE CRITICAL VOICES?

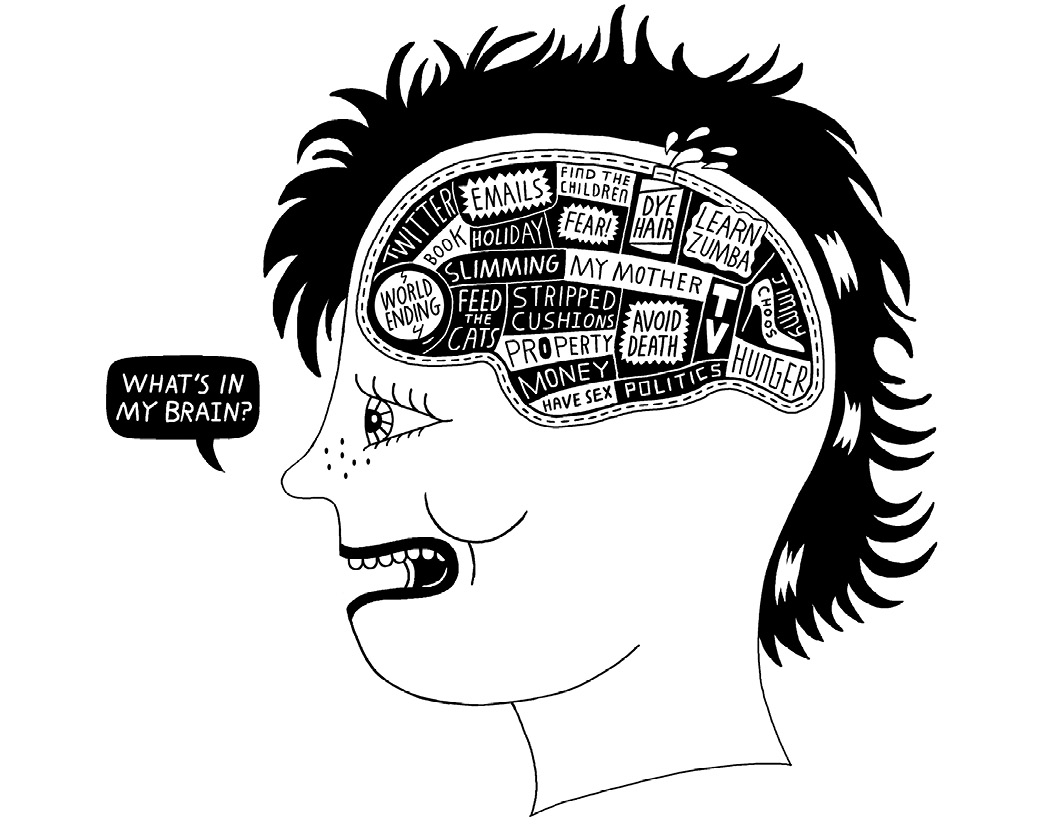

We have this proclivity for negative, nagging voices in our head because of that old fly in the works, survival. Every cell in us wants us to last long enough to pass our genes to the next generation, then we can go to hell as far as they’re concerned. Part of our brain still thinks it’s four hundred million years ago so that we’re on the constant lookout for predators who once killed us. Even in a resting state your brain is still tracking the horizon because back then there was so much lurking and we could do something about it, like run. Now, it’s not enough to just run from what we perceive as threatening; we’re helpless in the face of twenty-first-century danger: economic bedlam, out-of-control climate, and far-away countries that might be hiding bombs. No wonder we’re stressed.

This is why we’re overvigilant with paranoid feedback: “Look out for that . . . Don’t screw up . . . Those people hate you.” You’re reacting just like your cat that hunches his back and hisses, but you’re hunching with words. It’s the anxiety that keeps you on your toes. Close your eyes for a second, take your eye off the button, and you’re lunch. You can see why a glass half empty is our natural state.

The brain detects negative information faster than it does positive. We are drawn to bad news. When something is flagged as a negative experience, the hippocampus (responsible for consolidating memory) makes sure it’s stored in an easy-to-reach place for future reference. If you whistled a happy tune and just thought lovely thoughts, you’d probably be hit by a truck pretty quickly and find yourself as road kill. This negative bias primes you for avoidance and fear, but when you direct it at yourself, it can bring you to your knees with depression.

WHY DO WE NEVER HAVE ENOUGH?

Science tells us that the reason we “want” is that we are driven by a chemical in our brains called dopamine, and when we get something we want, we reward ourselves with a hit of it, which creates a buzz, a kick, a thrill. It’s like cocaine (which I never tried but heard about from other people, I won’t name names, but I was told it is the same high). If you lust after something very badly (say a pair of shoes) and then manage to buy them, you get a dollop of dopamine, which motivates you to immediately start planning how to get the next pair. (This insane version of forward-planning was handed down from when we foraged for nuts or whatever we foraged for hundreds of millions of years ago. We’d find nuts, eat them, and then immediately start making mental roadmaps of where to find other nuts in a similar terrain to the one we just scored. We probably didn’t even notice we were eating the nuts because we were so busy thinking about our next forage.)

But back to shoes. These days with the ants in your pants from the dopamine, you’ll need to find out how and where to get more shoes so you’ll begin to close in on shoe-rich environments—that is, malls. You’ll start sniffing around Jimmy Choo shops and might even empty your bank account to buy some, and the more you make that connection between malls and buying Jimmy Choos, the more entrenched and deeper that habit gets. After a while even if you just smell a Jimmy Choo shoe, your dopamine will run riot. If you go to a fancy dinner party and someone is wearing a Jimmy Choo shoe, you’re now so primed to “get shoe” that you might gnaw her foot off to get that buzz of excitement back again. With dopamine it’s the craving; that’s what drives you, not the actual shoe. It’s the chase—the thrill of the hunt driven on by cues in the environment that predict the next shoe around the corner. Dopamine does not always generate pleasure but impels you to seek rewards. You can be a very unhappy addict.

If, on the other hand, you don’t get the shoes, the dopamine decreases in your system so you start to get feelings of withdrawal similar to going cold turkey from a drug; you get all itchy and scratchy like everyone does in Breaking Bad. It’s like we have a meth lab in our basement. You’re informed about this by a part of your brain called the basal ganglia, which acts as a thermostat, registering stimulation coming in from the senses. Once the hunt becomes less novel you lose that motivational “oomph.”

At first, the basal ganglia is your best friend; it gets you high, you’re cooking with gas, you want to party but when you can’t get enough, boom, you’re a junkie on skid row. We are our own walking pharmacies shooting ourselves up with homemade chemicals. This constant need for a fix to make you feel good prompts you to pursue rewards over and over again and strengthens the behavior that made you want to get them in the first place. It’s a vicious circle.

So the reward system is necessary for your survival; you can use it for positive effect in order to increase your motivation for the healthy feeling of satisfaction for a job well done. But it can also push you so much into overdrive that it will run you ragged in your desire to achieve the unachievable. We need to be aware of each of our individual tipping points to differentiate between when we are on a high of creativity and production and when we are burning the engine. Our culture promotes an endless need for fulfillment to always want what the next guy has, even though the effort might kill us.

A LITTLE HISTORY OF HOW THEY FOUND OUT WHAT’S WHERE IN THE BRAIN

Having answered some of the questions raised in Part 1, I am going to name names as far as the mechanisms of the brain go, so that when I discuss mindfulness in Part 4 you’ll see how you can intentionally change the physiology of your brain (neuroplasticity) and thereby regulate your thoughts and feelings.

In 1861, the French anatomist Pierre Paul Broca opened the brain of a patient (after he was dead) who could speak only the single syllable tan. That’s all. Imagine going on a date with this guy—repetitive or what? Anyway, Broca noticed a lesion growing toward the back of the frontal lobes and suspected this damage might be the cause of the speech problem. Broca decided that this must be the area responsible for speech and called it Broca’s area. Tan couldn’t argue. All he could say was, “Tan tan tan.” A tragedy.

• • •

After that it was like a gold rush. Everyone started to open everyone’s head to find out what part was responsible for what. They all wanted to get a piece of the action and name some real estate in the brain after themselves. It has never been a dream of mine to have a tumor named after me, but the next guy to get famous on discovering a lesion was Wernicke who, in 1876, found an area below Broca’s area and he claimed that damage to this area was why one of his patients (another dead fellow) couldn’t string words together. He knew the words but could not create a sentence that made sense. So his patient would say “catfoodgaloshesheadmakecakeonmyhands.” Obviously, he couldn’t argue with Wernicke, so this area became known as Wernicke’s area. To recap, Broca was the discoverer of the “no speech” area and Wernicke was in charge of the “not being able to string a sentence together” zone. It’s a good thing the two patients never met. It would have been a dull party.

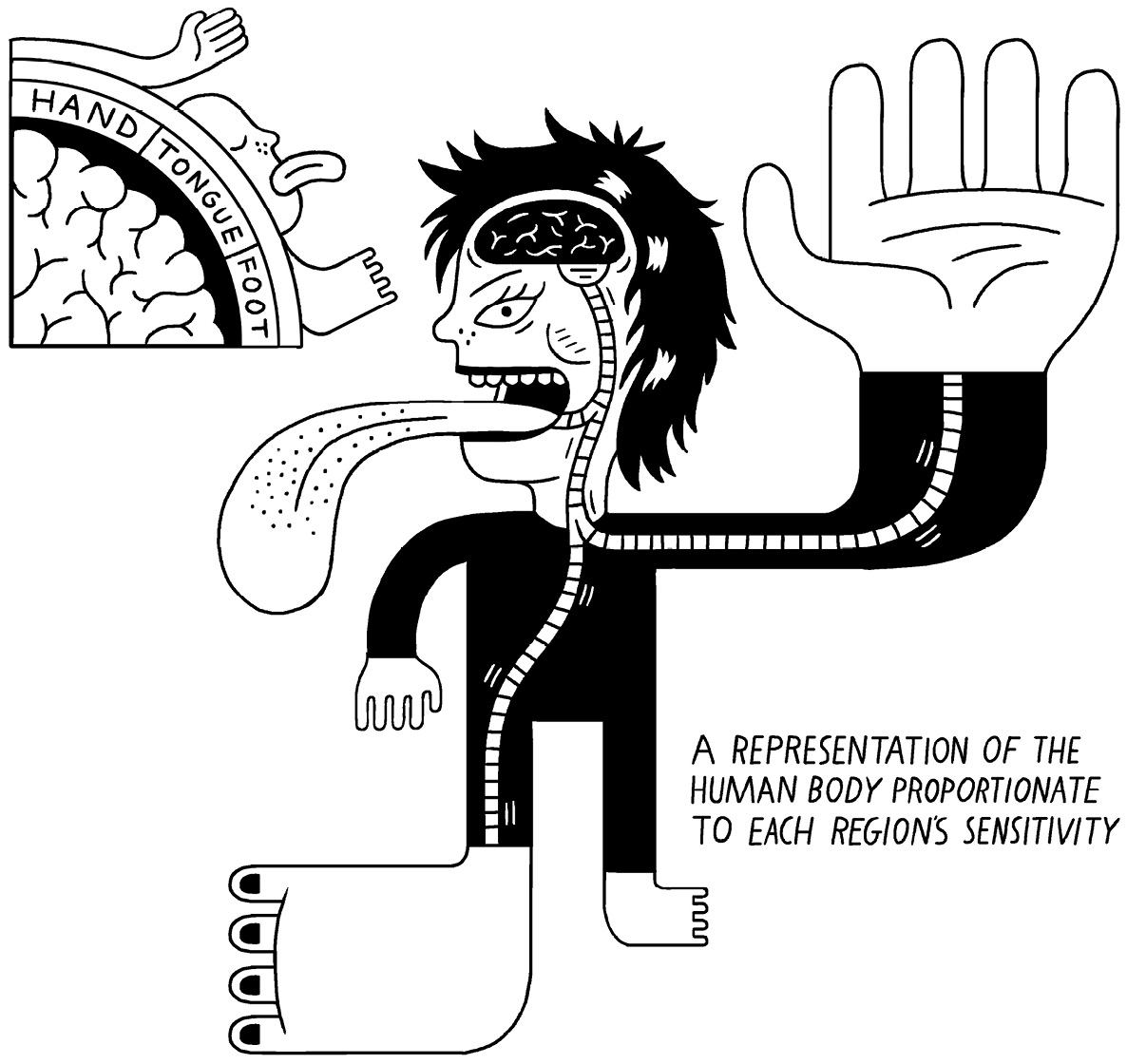

From this, neuroanatomists went into a frenzy and found that right across the top of our brain, from ear to ear, all humans have a somatosensory cortex where the brain receives signals from points on the surface of the body and registers them as touch. God knows how they found this out. I don’t even want to know, but this is where the brain registers the sensation from every part of the body. So if you stuck a pin in the area in your brain that represents your third toe you would feel pain in your third toe. In this somatosensory cortex there is a whole map of every region of your body not in the order of your parts from your head to your toes, but rather in order of what areas are the most sensitive.

This goes for every single area on your skin: an elbow area, thumb area, and genital area all have plots of real estate up in this somatosensory cortex where they can be felt. The size of the area relates to how many nerves you have in the specific region; the genital area and land of tongue are huge, because they are highly sensitized, while elbowville is not so huge. The county of shoulder—teeny. It’s as if your body parts are getting bigger plots if they’re used; genitals and tongue the size of Texas, armpit is Chattanooga.

If you had your foot amputated, you would still feel it in the foot neighborhood of your brain, thanks to a syndrome known as “phantom limb.” And if certain parts of your body become injured or diseased, neurons will grow to compensate for the missing part. What I love most is the fact that because the areas for the genitals are near the area for the feet in the somatosensory cortex, some people have reported that they feel they’re having an orgasm in the area of a missing foot. Once these discoveries about the brain’s wiring were made, all such bizarre syndromes started to make sense.

After this, neuroanatomists found and investigated movement maps of the brain. One such map was the motor cortex, which runs from one ear over the top of your brain, like headphones, and each point controls a different part of the body. So rather than receiving incoming sensations like in the somatosensory cortex, the motor cortex sends signals out, telling certain areas to move. If you stick a pin in the motor cortex area for your knee, your knee will twitch. If you stick the pin in the hip zone, the hip twitches; it may be possible to stick pins in certain parts of someone’s head and make them walk like a chicken.

But back to science. It was also discovered that if you stuck a pin in one area of a person’s cortex and his finger twitched, that if you then stuck a pin in the exact area of another person’s motor cortex, his finger might not twitch but his lip would. This is proof that each person is not created equally. Your cortical maps are all different sizes, depending on which part of your body you use the most and the least; the more developed parts have larger corresponding brain regions.

The man who discovered this was a real hero of neuroplasticity: Michael Merzenich, a postdoctorate fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

He found that if you’re a pianist and you practice moving your fingers up and down scales, hour after hour, day and night, more neurons would grow in the motor cortex of the finger area of the brain and expand its topography. I used to have a piano teacher who slammed the lid down while I was playing if I made a mistake, which is probably why I confess to war crimes whenever I see a piano. If you were a flamenco dancer you’d have more real estate in the toe area of your brain. Someone who licked stamps for a living would obviously have a larger tongue terrain. Do you see where I’m going with this?

When you’re building up clusters of neurons by habitually moving certain parts of your body, it’s like building muscles when you pump iron. In both cases the movement gets easier and more automatic because that area gets stronger. Of course, neural exercise doesn’t give you bigger pecs or a six-pack, so you have to choose brain or brawn. It’s very rare to have both. (See Arnold Schwarzenegger.) But there’s more than one way to be attractive and looks aren’t everything, or so I tell myself.

WHAT’S GOING ON IN YOUR MIND?

First let me say we’ve come such a long way from where we started. From a one-celled amoeba, a tiny pinheaded thing clinging onto a rock, to an evolutionary orchestrated masterpiece; our brain, which looks like a three-pound piece of tofu. This jellylike substance has more horsepower than every supercomputer that ever was, squared. It has two hemispheres and various lobes, each of which plays a crucial role. Zapping throughout our inner landscape are approximately a hundred billion neurons, electrically transmitting information, sending it at the speed of light throughout our whole nervous system. These hundred billion neurons can have anything from ten thousand to a hundred thousand branches or dendrites or connections (for the less bright), and every time you learn and experience something, they get better at firing, and the wiring gets denser, creating a serious forest of brainpower. I have heard it said that the brain is capable of more connections than there are stars in the universe (how they counted this I have no idea and maybe they’re making it up). It’s hard to believe that each and every one of us carries this equipment, even reality TV stars. What a waste.

And yet we still have many glitches; we are not Homo perfectus yet, far from it. We all basically have similar problems since we share the same plumbing. We all have cracks. We just hide them from each other.

Our brain has been shaped by evolutionary pressure over time to provide our bodies with ever more efficient ways of surviving and reproducing. It is designed to process all information for the purpose of living on, it doesn’t care about happiness—it has things to do, places to go. So you may want to just swim with dolphins for the rest of your life (and some do) but most of us are primed to be busy: to go get, to provide food on tap and a roof over our heads in order to be able to get the best mate possible for gene purposes. (Google “trophy wives and sugar daddies.”)

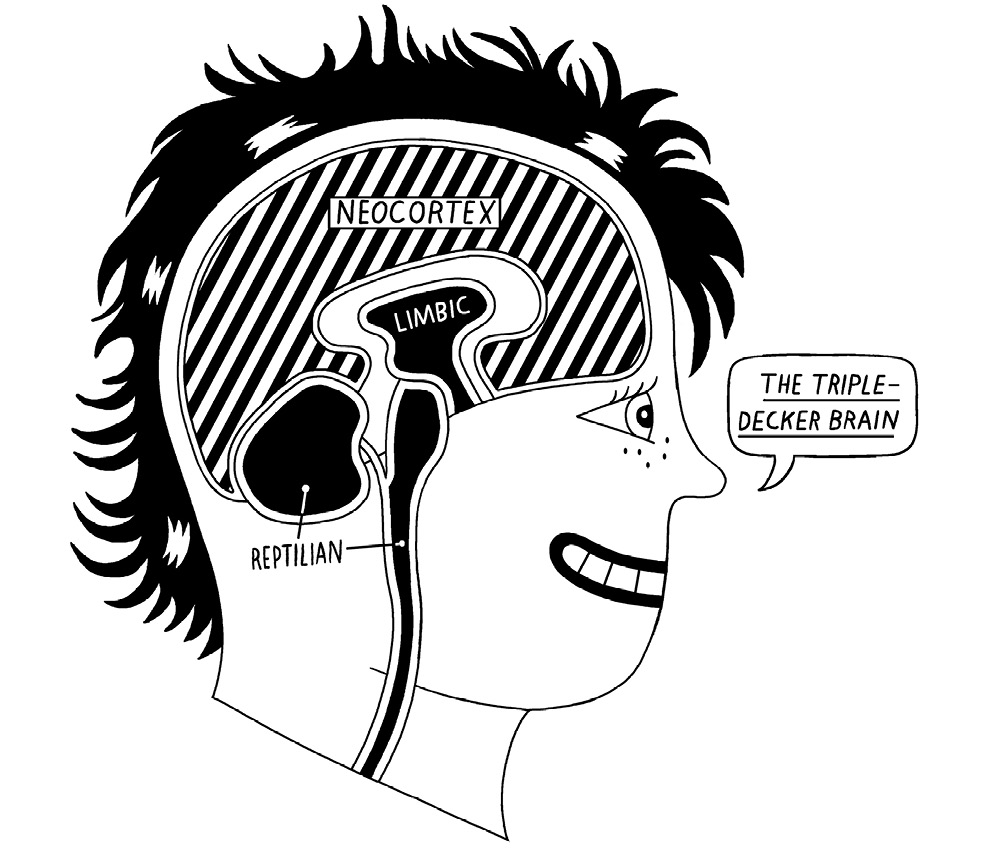

THE TRIPLE-DECKER BRAIN

The cause of much of our confusion is that we actually have too many brains in our heads. Three to be precise. Starting with the oldest brain, the other two newer ones are outside it like Russian nesting dolls; a brain within a brain within a brain. Unfortunately our old reptilian brain didn’t get absorbed; it’s still in there squashed with the newer models, like a relative you can’t get rid of.

This ancient brain, developed about four hundred million years ago, is called the brainstem; it is the “duh” part of the brain. It prompts us to mate, kill, and eat, which is perfect if you’re living in a field or working at Goldman Sachs.

Then around 250 million years ago, the paleomammalian brain (but that’s way too long a word), or limbic system, came online; that’s where we, unlike reptiles, were motivated to bond with and nurture our offspring, rather than eat them. (Not such a bad idea when you think about school fees.)

During our neomammalian phase, about five hundred thousand years ago, we grew a superior brain, the prefrontal cortex; the executive brain, El Capitano. This provided us with the tools for self-control, consciousness, awareness, language, and self-regulation. Also for rational, strategic and logical thought; math; and morality. It is the gatekeeper to the primitive brain, so if you suddenly want to eat without a fork, it will inform you that it isn’t such a good idea. Same with peeing in public. The brain tripled in size in the last three million years (which of course is a blink in the history of us), and we suddenly got the ability to feel sorry for each other and acquired cooperation skills like group hugging. (See New Age.)

This mishmash of three brains, called the lizard-squirrel-monkey brain, all trying to function at once is one reason why we’re nuts. This is why there are women who read Heidegger but who also want to screw the plumber.

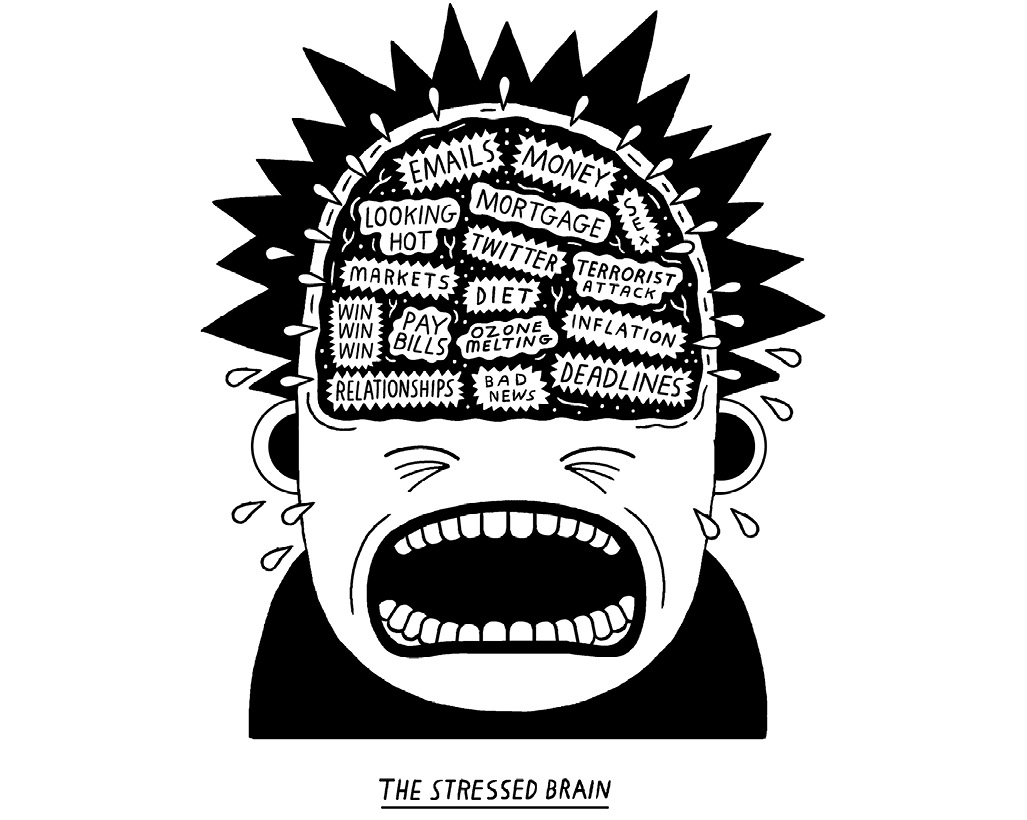

I will explain where things may have started to go wrong for us: errors thanks to evolution. Millions of years ago, when we were ancient man, as I have said, we were perfectly fine and at one with our environment (no one had panic attacks or OCD). When we met a predator and felt danger or a threat, we’d fill up with our own adrenaline and cortisol to take on our foe. Kill or be killed. Have lunch or be lunch. After the ordeal was over, we’d defuel and the chemicals would go back to normal.

The problem these days as modern man is that when we perceive danger, adrenaline shoots into us but because we can’t kill a traffic warden or eat a real estate agent, the juice never comes back down. We’re in a constant state of red light alert, like a car siren that drives you nuts.

Because we can’t kill people who anger us, we have all this pent-up rage. To make things worse, when language came online, about seventy thousand years ago, we started to use words to describe those constant feelings of alarm, so everything was perceived as an emergency. Now, it wasn’t just, “Oh, there’s a sabre tooth tiger,” it was, “Oh, I forgot to send that email,” “Everyone hates me,” “My thighs are too fat,” “I didn’t get invited to the Christmas party.” This is what drives us mad: the never-ending voices.

The thing that helped us survive in the past (our alarm system) now gives us nervous breakdowns. Someone said, “Man was built for survival, not for happiness.” Sorry to be the bearer of bad news but our pets are happier than we are. Cats, happy happy. Dogs, happy happy. Human beings, screwed. Completely screwed.

A LITTLE ABOUT STRESS

These days we are more likely to die in different ways from our ancestors. We (in the West) no longer have to worry about scarlet fever, bubonic plague, or cholera. In the 1900s, the big diseases were tuberculosis, pneumonia, and influenza. A person living through World War I was more likely to die of flu than in battle. Now because we’re living longer and better than ever before, we slowly fall apart.

Out on the savanna, our physiological responses were perfectly suited to deal with stressors (run from the big animals with big teeth). These days we can’t just run from what drives up our anxiety and stress: mortgages, money problems, looking hot, relationships, and deadlines. Evolution did not set us up to suffer Jurassic Park levels of stress, day in and day out; that’s the bitch of living at today’s pace.

You say, “Oh, come on, you lightweight, we can deal with stress, bring it on.” It isn’t the stress that makes you sick or even your risk of being sick. Stress increases your risk of getting diseases that make you sick, or if you’re already sick and you add stress, you can kiss farewell to your natural defenses. The fact we can’t switch off our alarm is what makes us vulnerable. So here’s my point: stress-related diseases are disorders of excessive stress responses. (Take it or leave it.)

With mindfulness, you learn to regulate these chemicals, intentionally increasing the ones that promote health and happiness and decreasing the ones that don’t.

As I said before, you can be the creator of your own stress without any outside influence. As soon as you even think about stress, a whole cascade of reactions happen: Your thalamus (the relay station of your brain) sends out a wake-up call to your brainstem; signals are sent to all your major organs and muscle groups, getting them ready for fight or flight; and your adrenal glands release the stress hormones. Cortisol suppresses the immune system to reduce inflammation from any injuries and stimulates the amygdala to keep you vigilant, which produces even more cortisol. It also suppresses activity in the hippocampus, reducing your memory so that you think about only what you did last time you had a similar emergency. Eventually, the actual neurons in the hippocampus (where some of your memory is stored) will burn out; the more you stress the blanker you’ll get. Ever study insanely for an exam and the next day go blank? You’ve burned out your memory for the sake of a test.

This chemical also stops your digestion and the urge to have sex. (Although there are some people who like to have sex during a hurricane.) Thinking about sex or eating during a disaster would only make things worse. Another chemical, epinephrine, increases your heartbeat so it can move more blood and dilate your pupils (to help you find your foe in the dark). All this is useful if you’re actually in danger. If you’re not actually in a life-or-death situation and those chemicals can’t stop pumping through you, they will wreak havoc on your body and brain. Excessive chemicals eventually inhibit your immune system (the defense against infections and illnesses), making you vulnerable to viruses of every shape and size. They will lower the production of serotonin (making you feel listless and joyless as in depression) and can eventually, if they remain virulent, contribute to heart disease, hardening of the arteries, type 2 diabetes, obesity, infertility, premature aging, and certain cancers. Inadvertently stress will destroy you both mentally and physically unless you change the way you think about it and relate to it.

With mindfulness, you learn to regulate these chemicals, intentionally increasing the ones that promote health and happiness and decreasing the ones that don’t.

PARTS OF THE BRAINS: THE EASY-TO-UNDERSTAND VERSION

“Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start.” I like to quote Julie Andrews when discussing neuroscience. The pattern of how neurons or cells are wired together determines the way we think. Whatever we experience mentally is a result of the different combinations of neurons. As I said earlier, each neuron can link up with ten thousand to a hundred thousand neighbors and make connections. The parts that join up are branches or dendrites (which receive incoming information) and axons (which send signals).

The inside of your head could be compared to Las Vegas, where every experience, sensation, thought, and feeling corresponds with billions of electrical lights zapping on and off like a stadium wave on a gigantic electric grid. Your ability to do everything—including your dreams, hopes, fantasies, fears, and most of all your ability to read this book—is created by neuronal connections, chemicals, and specialized regions in your brain calibrated by your genetic history, your development, the society you’re born into, and of course, Mommy and Daddy.

Neurons transmit information to each other via electrical impulses not dissimilar to those used to jolt Frankenstein’s monster up from the gurney and make him kill people. When a neuron fires, an electrochemical wave ripples through it, on its way to signaling the next neuron.

You may have learned this at school, but I will remind you that the neurons don’t actually touch each other; between each of them is a tiny gap, called a synapse, across which chemicals are passed (called neurotransmitters). When neurons become excited through enough stimulation (because of a thought or experience), an electrical wavelet fires down the length of the cell to activate or inhibit the neurotransmitters. At the other side of each gap are little receptors, like flowers opening to pass the chemicals across the synaptic cleft and lodge in the next neuron. Once they cross over they create an electrical zap that sends an electrical message to the next neuron. This is how neurons communicate with each other through electrical and chemical impulses—and those babies can go from speeds of two to twenty miles per hour. The whole process is not dissimilar to a game of hot potato but electric. Just think, all this is going on inside your brain, right now and you’re just lying there without knowing it. You should get on your knees and thank evolution.

Learning is about new neurons connecting together; memory is made possible by those changes happening over and over again to embed the new pattern. When neurons fire many times because you’re memorizing a new fact and you study it again and again, your synapses are actually changing their shape to speed up receptiveness and increase the firing, making them more efficient at passing information in the future. Learning has happened because of the synapse changing shape, and the longer the shape is retained, the longer you hold that information. Use it or lose it. If you repeat a mode of thinking or behaving, the pattern of the neurons becomes strengthened. Neurons that fire together, wire together. When they don’t fire, the connections eventually just shrivel and die like the Wicked Witch of the West melted when they threw water on her.

Your average neuron fires five to fifty times a second, meaning there are zillions and zillions of signals traveling inside your head right now carrying snippets of information. The nervous system moves information exactly like your heart moves blood. All those zillions of emails zapping around in your head are what define the mind, most of which you will never be aware of. The number of possible combinations of a hundred billion neurons firing or not firing is ten to the millionth power, or one followed by a million zeros. (I’m just trying to show you there’s a lot going on in your head.)

As more and more complex skills became part of your repertoire, from rubbing sticks to make fire to building a rocket, more and more neural cells connect and grow, and these dendrites or connections become stronger and stronger and more and more synchronized in their firing patterns. If you learned Mandarin, you’d get a whole set of synchronized neurons in the language department, or if you take up banjo, a whole bunch of neurons are lighting up in your brain in your finger area on the somatic map in your brain. Whatever you’re doing or thinking about is reflected in areas lighting up in your brain, and you can watch this firework display during brain scanning.

Everything that happens, every thought, feeling and perception you have, changes your brain, and those changes are how you learn things, from bowling to dumping your boyfriend. However, the brain isn’t just a mass of unspecialized information processors; it has distinct regions that do specific jobs.

Neurons (with their shooting neurotransmitters) form into pathways and multiple networks with specialized functions and via these pathways the regions are able to communicate with each other, the way a subway system works going from station to station. All information processed by the brain is nothing more than electricity passing through neuron after neuron with little squirts of juice across their gaps. (Not very glamorous sounding, I know.)

Genes

Genes hand you a deck of cards; how you play them is up to you.

I can hear you ask, “What about genes? Don’t they play a part in all this?” No one knows how much your genes contribute to make you who you are or how much your experience shapes you. Nature (referring to genes a person has inherited) or nurture (influenced by environmental factors)? It’s a toss-up. Genes hand you a deck of cards; how you play them is up to you. A gene is a unit of hereditary information linked to one or more physical traits: leg length (I’m furious I will never go down the catwalk with what I’ve got), blond hair (another thing I wished I had), and larger lips (a must for my modeling career). Your genetic code (the blueprint of you) is contained in your DNA and informs each and every cell where to go (which is why your ear doesn’t grow out of your foot), so your DNA is like a traffic cop, directing trillions of cells, determining what each cell actually becomes, and killing off those that make a wrong turn.

Genes create proteins, and they can turn that gene expression on and off, up and down. In the brain, gene expression influences levels of neurotransmitters, which influence functions like intelligence. This is why some people get A’s without working for them (I hate them). Or they influence memory, for those who win quiz shows about general knowledge (I hate them too).

The environment also influences gene expression, so how your brain works and who you become depends on diet, education, and the color of your wallpaper.

We have around thirty-one thousand genes, and they don’t all get switched on, no matter what Mommy and Daddy passed on to you. Good news for those of you with crazy parents. You might be just fine, depending on your experiences. Some behavior is more heritable than others; you might start off with some genes loaded for depression, but they don’t just switch on without environmental input. No one knows if you become you because of nature or nurture; it’s a combination of what you’re born with and how you live your life.

In our early years we are vulnerable to bad environmental experiences, so Mommy and Daddy can seriously damage your gene expression. Each baby is, in the first five years of her life, at the mercy of her parents’ download . . . and they got their downloads from their parents . . . and all the way back to the baboon and beyond. (It’s a miracle we’re not still swinging from trees. Next time you see royalty, just picture their forefathers squatting in the bush.)

The brain is divided into four lobes. Form has function and I’m going to tell you about it, at least all that I know.

Just a note, the brain is much, much more complicated than my humble descriptions; many regions overlap in their functions, and cognitive neuroscientists spend their days figuring out what each of the specific regions do. In a way, they’re still in the dark and so am I. The following is just a broad sketch—so if you’re a neuroscientist don’t bite my head off or any one of my lobes.

FOUR LOBES: EACH LOBE HAS A RIGHT AND LEFT SIDE

Occipital Lobe

The occipital lobe is responsible for most of our visual processing. We don’t actually see the world through our eyeballs; instead light shines through the retina and sends projections to different groups of neurons in the occipital lobe, each one specialized to interpret various components of visual information. For example:

Orientation

Shape

Light and shade

Face recognition

This lobe works in conjunction with other regions (parietal and temporal lobes) that are organized into streams of visual information, such as the “what” pathway determining if it’s a chair, cow, or your mother and a “where” pathway telling you, in your house, in the yard, on your face.

So, contrary to popular belief, it’s not your actual eyeball that sees the world; you have a whole production company in the back of your head beavering away, producing a movie, creating the illusion that what you see is real. It’s a film called Reality rather than actual reality. So many things are going on back there in the occipital lobe, and this is how you can remember a face or a scene and say, “Oh yes, I remember who you are, didn’t I marry you ten years ago?”—something I’ve been known to say to my husband. Now I know why.

Temporal Lobe

The temporal lobes, located around the ears, gives you surround sound (auditory perception) and provides you with your ability to comprehend language and meaning (hello, existentialists), carries out emotional processing (in the amygdala), and is the home of specialized “explicit memory” centers such as the hippocampus. When there’s a strong emotion during an experience, chances are you won’t forget it thanks to structures in your temporal lobe. Say on your tenth birthday you saw a horse fall off a cliff and you became hysterical. That magic photo opportunity will be locked in your long-term memory thanks to the temporal lobe. Emotional memories stick the longest. That’s why when you’re memorizing history in school, you should picture yourself in the Battle of Hastings and pretend to lose your legs. You won’t forget it then, I promise.

Parietal Lobe

The parietal lobe integrates sensory and visual information, so that you can navigate with a sort of internal compass to tell you where you are in space and give you a sense of being in your body. It then coordinates your movements in response to objects and tells you where and what they are, constantly updating the information as you move and interact with the world. This navigation system is a must to stop you from crashing into the furniture.

Frontal Lobe

The largest of the brain’s structures is the frontal lobe. It is what makes (most of) us civilized and creates our personalities; it is the big boy of mental ability. This is the seat of our emotions and allows us to understand how someone else is thinking and feeling. It can plan a whole scenario so we can rehearse an outcome before we initiate it. Among its list of accolades are some of these babies:

Decision making

Problem solving

Judgment

And, best of all, emotional impulse control or self-regulation

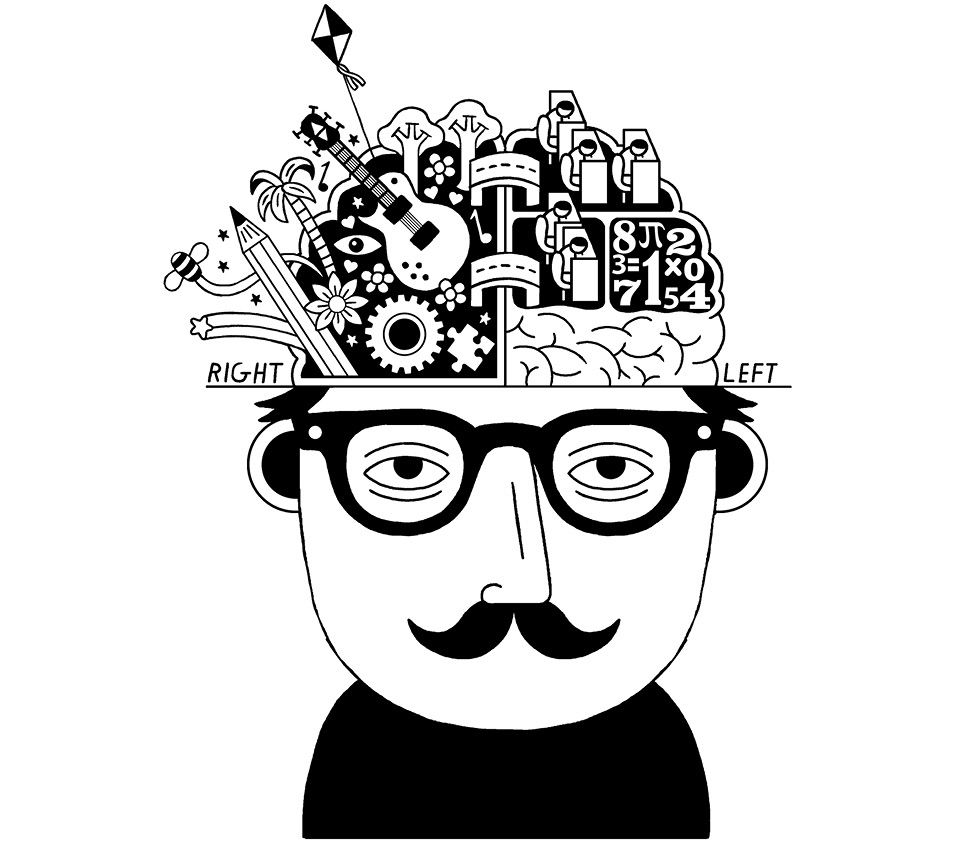

RIGHT AND LEFT BRAIN

Corpus Callosum

The two hemispheres are connected by the corpus callosum, a bridge made of a densely packed band of nerve fibers shunting information back and forth and facilitating a continuous dialogue between the two halves; if this didn’t exist, your left side wouldn’t know what your right side was doing (and could play very cruel tricks on it). Luckily, it can seamlessly create the illusion that you are the result of one brain rather than two. Each hemisphere controls the movement in the opposite side of the body.

Contrary to popular myth, the right brain is not just the female feeling part of the brain and the left, the macho business side. It’s more complicated than simple ladies’ and men’s signs on restroom doors: These two sides took hundreds of millions of years to develop, and evolution wouldn’t come up with something that flimsy. The two sides share many features, and yet at the same time each side has specialized processing systems. Each side seems to compensate in strength for what the other lacks. The right isn’t good at grammar so the left is spectacular at it. The right is touchy-feely to get the big picture, while the left is better at reading, writing, and doing arithmetic and sweats about the details.

Perhaps from early in our evolution one side had to have narrow focus to find food (left) while the other side (right) had to be on the lookout, vigilant at watching out in case we were jumped.

Some Skills of the Right Side

Not great at grammar or vocabulary but fantastic at picking up intonation and accent

Creative

Intuitive

Skilled at putting pieces together (great at puzzles)

The home of autobiographical memory—the story of you

Picks up metaphors and jokes

All the information from the right is then sent to Lefty for interpretation.

Some Skills of the Left Side

Linear

Logical

Able to plan

Accurate and able to think literally and retrieve facts

In charge of vocabulary

The area responsible for those internal voices (boo hiss)

The narrator of your ongoing personal life story

The region where list-making lurks (boo hiss)

The left side is more densely woven with closely packed neurons, making this side better at doing intense, detailed work. These left-brainers are brilliant but can be very boring people. If there’s too much left-brain, analytical, and logical thinking, you may not be a very warm and cozy individual. They make great businesspeople but are not always great fun. Asperger’s-like symptoms (though less pronounced) are an advantage for these folks who need to focus on one particular thing and everything else can go to hell. Some people think this gift of pin-size focus is an asset in the information age. Left-brainers can sit for hours staring at a screen and nothing outside interferes.

Ideally the two hemispheres work together and make a perfect couple—that is, if the right gets a vibe that there is something dangerous outside then the left defines what it is. Creating a coherent narrative of your own life story involves the integration of the two hemispheres. Too much in the left you’ve got a boring accountant, too much in the right you get someone who talks to angels and probably can’t pay the phone bill on time.

PARTS OF THE BRAIN: PART TWO

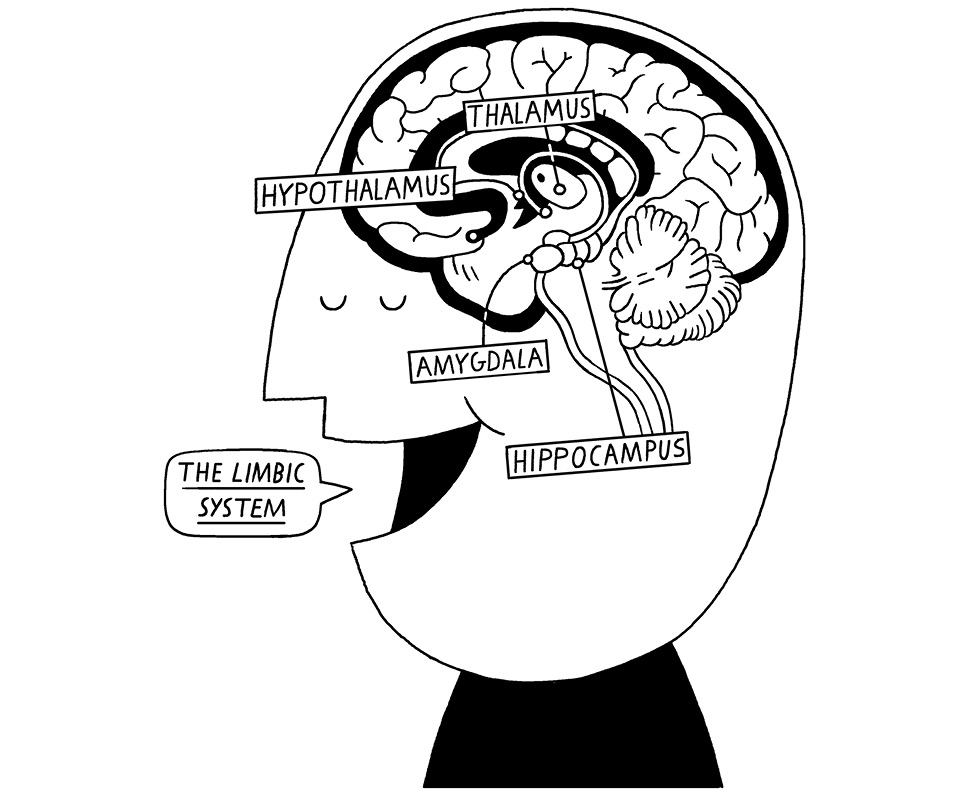

Right under the corpus callosum is the limbic system, the more ancient mammalian part of the brain. This part is good news for survival and motivation and bad news for civilization. Too much reaction from the limbic and not enough prefrontal cortex keeping you in check, and you might turn out to be a thug or similar.

A Few Parts of the Limbic System

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is involved with the translation of conscious experience into bodily processes; you think, then you move. It’s also involved in hormone regulation. Here are a few of the processes controlled by the hypothalamus:

Hunger

Thirst

Body temperature

Blood pressure

Sleep

Thalamus

The thalamus makes a wake-up call to the brain stem (the duh part of the brain), sending signals to all major organs and muscle groups (like a call center that redirects incoming traffic to the appropriate area) and, if need be, gets you ready to rumble or run. All sensory information (except smell) is passed and processed through the thalamus. It’s thought to be involved in consciousness because if you lose power there, you’ll find yourself in a coma.

Hippocampus

Shaped like a seahorse, the hippocampus works like a search engine to locate and retrieve other memories quickly and smoothly, like a great secretary who knows where all your life is filed away.

Amygdala

The emergency alarm of the brain, the amygdala, sends responses to various parts of the body from emotionally relevant information. It coordinates physiological responses to get you ready to fight or run and makes sure you remember it for next time.

A Few Parts of the Frontal Lobe

Prefrontal Cortex

The “higher part” of the brain is the prefrontal cortex. It helps with assessing and choosing the correct social behavior (it’s the “pinky up” part of the brain when you have tea at the Ritz) and has numerous other talents:

Higher thinking (planning, reasoning, judging)

Self-regulation

Impulse control

Anterior Cingulate Cortex

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is the overseer of attention. It monitors predictive errors and conflicts, such as the distance you are from your goals. It is the basis of working memory; a workspace where you can gather information and solve problems and make decisions. It’s also where actions are planned. The ACC comes into its own when you:

Gather information

Solve problems

Make decisions

Plan actions

Fulfill your intentions

Self-regulate

The ACC doesn’t develop until you’re between three and six years old; this is probably why kids have hissy fits.

Orbital Medial Prefrontal Cortex

The orbital medial prefrontal cortex regulates information from the external and internal worlds, especially in relation to reward. Its inhibition function can say, “Whoa boy,” to the amygdala before it sends out the full alarm to “kill or run” or other embarrassingly primitive reactions, such as defecating on the carpet or having sex in an elevator. Using these reins makes you polite even when you want to chew someone’s head off.

Somatosensory Cortex

As mentioned earlier, the somatosensory cortex is a region in the brain that has a map of all your body parts. The map isn’t in order from your toes, knees, and thighs up to your head. It’s in the order of which parts are the most sensitive, so the lips are right next to the genitals (an R-rated anatomical joke).

Insula

All those internal “vibes”—the feeling of butterflies flapping their wings in your stomach or knives in your heart—come from the insula. This area gives you a visceral weather report from inside. If you sense these feelings and link them with the ACC, you can then reflect on them and consciously make a decision if you want to pull the reins or not. (I’ll be discussing this later because the ACC is responsible for self-awareness and regulation, which are strengthened by the practice of mindfulness.)

Cerebellum

The “small brain” at the tail end of the big brain leading to the spine is the cerebellum, which is in charge of balance, posture, and coordination.

Basal Ganglia

The basal ganglia is an area involved in motivation, motor selection, and action. It controls everything from big muscle movements to the flicker of the eyes caused by surprise, novelty, cravings, or drive. It uses our memories and translates them into motivation and then action. If it were to be removed, you’d be more like a doormat. (Don’t try that at home!)

The Chemicals That Make You Who You Are

You know the expression “It’s just the hormones talking?” This is usually said in a derogatory way to women who are having their period. Just because I have threatened people with a buzz saw through their car at this time of the month, I am categorized as hormonal. But ha-ha, it’s not just us. Men, children, even pets are at the mercy of the hormones that dictate their moods. When you fall in love, it’s not because someone sprayed fairy dust on you, it’s just a hormone within that has been switched on. Think about sex. That’s OK I’ll give you a few minutes. It gets complicated, but to give you an idea, when a thought occurs it sends a message to your thalamus, which emails the pituitary gland, which in turn phones the adrenal, which sends hormones responding to the original thought. Maybe we’re all just different recipes; recipes with legs. When someone asks how you are, you should just hand him or her a list of your ingredients. This is far more accurate than a star sign if you ask me.

Here are some of those ingredients and their main functions. There are more than one hundred different agents known to serve as neurotransmitters and many of these have different functions in different regions of the brain.

Serotonin

Serotonin is the feel-good chemical. People who have a lot of this in their systems aren’t people pleasers. They feel good just being themselves. I have very little of this; I have to buy it over a counter. Your doctor can prescribe an antidepressant, so you don’t have to suck it out of a friend’s neck if you’re low on it. It can turn anxiety into serenity and optimism, but it also affects other areas: appetite, blood pressure, and pain levels.

Dopamine

As I’ve said, dopamine motivates you to seek rewards. Cocaine does the same thing, but it’s more expensive. Dopamine switches on (the basal ganglia lets you know you’re running low) when you anticipate getting what you want, which is why the chase tastes better than the kill; it lights up under the scanner when we know we’re just about to get our object of desire. Experiments on rats have shown that they’ll give up food, sex, and rock and roll just to get a hit of dopamine. That’s how good it feels, and rats are no fools.

Those driven, ambitious, A-type personalities are high on (perhaps among other things) their own dopamine, so they keep it on a constant drip, always seeking situations that jack it up a notch.

Noradrenaline

Noradrenaline is also called norepinephrine. It influences sleep and attention; it excites, alerts, and arouses. This is your “get up and go” hit. It starts your heart racing and blood rushing, but too much noradrenaline, and you find yourself in fight-or-flight mode. When a squirrel lifts its little head and jerks it around to look for trouble, he’s on norepinephrine.

Acetylcholine

A shot of acetylcholine would make you whizz through university exams; it promotes attention, learning, memory, and neuroplasticity and is critical for control of muscles by motor neurons (it also keeps your heart pumping, so you don’t want to go to empty on this chemical). When acetylcholine is released, near the brain stem, it enables neurons that are activated to strengthen their connections to one another.

Endorphin

Endorphins reduce pain and stress and create a sense of whoopee! by suppressing shame, vigilance, and self-criticism so now you can dance on tabletops in your underwear with a flower in your nose.

Oxytocin

When oxytocin switches on, you’ll feel all cozy and milky like the perfect mommy. Very important to have while raising children; without it you’ll want to run in the other direction when they make noise. When you reach out and touch someone, your oxytocin is lactating. Those with a lot of oxytocin could be described as cuddly, wanting to take care and metaphorically breastfeed everyone. In the queue of life they’re always at the back taking care of others. (I have very little of this drug.)

Glutamate

Glutamate is the brain’s CEO as far as exciting the neurotransmitters and forging links between neurons via the synapses. It’s the most stimulating neurotransmitter for learning because it changes the way synapses work, thereby making it easier and more likely for them to fire. The more they fire the more engrained new knowledge becomes. The parts of the brain that use glutamate to communicate the most are the cortex and the hippocampus. Take out the hippocampus (a scientist did this by accident to one unfortunate guy) and you have around a thirty-second memory. (See Goldfish.) No glutamate and you can’t lay down any new memories at all. Knock out the genes for glutamate receptors in mice and you get mice who will never find the cheese again. (I’m not suggesting you really do that.) If you give mice more glutamate receptors you get supermice that are going for their second PhD.

Vasopressin

Vasopressin supports pair bonding, attachment, and monogamy. It decreases aggressiveness in males and turns them into caretaking and intimacy-seeking creatures who write Valentine’s Day cards and stay faithful. We should put vasopressin in their food.

Testosterone

Without testosterone you can kiss good-bye to an erection. Trust me, I know these things.

Cortisol

I talked about cortisol before; it is your friend and foe. It can get you going, put a tiger in your tank, or debilitate you.

• • •

As I mentioned, things are much more complex than I’ve described because these chemicals affect you in different ways, depending on where in the brain they’re switched on. For example, Parkinson’s disease patients have too little dopamine in an area of the brain that controls movement. If you increase their dopamine, the shaking stops but now there’s too much dopamine in other parts of the brain so you’ve got a guy who’s suddenly addicted to gambling or sex. Now he’s not shaking but he’s broke and making eyes at you. You see the problem? For depression it’s not as simple as increasing your serotonin because if you pump it in, it’s like cluster-bombing; what’s effective in one area may damage the next. Neuroscientists are still in the dark about antidepressants because how can they research what happens to neurons when there are hundreds of billions of them? (Like finding your contact lens in the Sahara.)

MEMORY

Here’s where knowledge of the brain gets fuzzy: around memory. Neuroscientists are unable to identify where memory is located in the brain; it seems it’s everywhere. If the amygdala is persistently stimulated or there’s a big enough shock, the synapses change shape, making them more sensitive to fear stimuli, and you’ll feel fear faster next time something similar happens to scare you. If the motor cortex is stimulated enough by firing neurons in that region you’ll learn the skills to whack a tennis ball or ski like an Olympian. Pain is learned through overstimulated neurons in the somatosensory cortex so, by merely touching something, the sensation is more easily triggered, magnifying the agony. So memory is the result of long-term potentiation causing the neurons to be more readily fired.

Most of the understanding about memory comes from either brain accidents or traumas. There was a guy named H.M. who, when he was nine years old, fell off his bike. He was fine for a while, but by age twenty-five he had started having severe seizures. To find a way to alleviate these episodes, the surgeon took out both the right and left sides of his hippocampus; no one had ever done that. He seemed fine but for a tiny problem: Whatever he did, he couldn’t remember that he had done it before. He’d eat and not know it and eat again. Each time he met someone it was as if it was the first time. (No short-term memory.) If you were a comedian this man would be your ideal audience. It became clear that you need your hippocampus to convert short-term memory into long-term memory. What was amazing was that he could remember everything before the accident, so his long-term memory was intact. Clearly memory is stored in other parts of the brain.

There are two major kinds of memory processes—explicit and implicit.

Explicit Memory

Your explicit memories are stored in the hippocampus and medial temporal cortex and include facts, events, people, and places. You need to make a conscious effort to recall these memories—for example, when was your first kiss and where? For me it was in my closet with God knows who . . . I was stoned. (I hope it was a person and not a shoe.)

Implicit Memory

Implicit memories are unconscious memories: When you learn to ride a bike, you’re firing off clusters of neurons that help you pedal and balance, and every detail becomes automatic so you don’t have to think back to remember them. Implicit memory is stored in various places in the brain; movement is stored in the motor cortex and cerebellum, and the memory of certain emotions is stored in the amygdala.

For the first eighteen months of our lives we encode only implicit memory: smells, tastes, sounds, bodily, and emotional sensations. The brain combines similar events and constructs mental models from repeated events. If Mommy hugged you repeatedly during childhood, you’d start to expect it whenever you saw her. This information is then embedded in your synaptic connections, which ultimately shape your brain so whenever you see Mommy or someone who looks like her, you’re primed to expect that hug. (I find these people particularly irritating, and even worse, they want a hug back. I am going to make a T-shirt that says “No Hugs.”)

Your hippocampus pulls together separate images and sensations from implicit memory, like pieces of a puzzle, into pictures of factual and autobiographical material.

In order to couple the details of an experience with an emotional kick, the hippocampus has to work with other limbic areas like the amygdala—this is why you’ll never forget the smell of the sea on the night your boyfriend threw you off a cliff.

When images and sensations stay in implicit memory and aren’t integrated by the hippocampus they remain disconnected from the past. This could explain the way you have flashbacks from traumatic experiences because you can’t identify the fear and panic as belonging to the past.

Autobiographical Memory

As time goes on, you collect and condense more and more episodic memories into larger files along a timeline. At this point you can start to tell funny or sad stories about different times in your life, compare various experiences, and create a narrative. As you elaborate these multiple episodes you eventually have yourself an autobiography; now you can write a book about the story of your life (whether anyone will buy it is a separate question).

How Memory Works

The mind is always recording whether you’re awake or asleep. We sometimes dip into our consciousness and maybe pick out a few random words or snippets of thought and embroider them together to form a tale. This random fishing in thoughts does not actually reveal who you are. I apologize to any Freudians reading this but scrutinizing the minutiae of your thoughts is like studying your feces through a microscope. If you learn about yourself from that, good luck to you.

Whenever you use memory, you’re retrieving it from storage in the various parts of your brain working together to create the remembered event. It uses the emotional impact—your fear, joy or shame—to color how you’ll remember something. The image is imprinted by what you felt. Also, your feelings in a situation will be as different from the next person as your fingerprint. This is why so many people remember the scene of a crime differently. We are all biased in terms of how we bring up the past. Each time a memory is recalled, it is an amalgamation from various sections of the brain. If you call it up again and again you get versions of old versions like an elaborate game of telephone, and each time it becomes more distorted.

Our brains collect images from the moment we’re born and file them away as either safe or dangerous. Whenever we see someone or something, we dive into our memories to see who that person or scene reminds us of. In our visual cortex there is a region for face recognition. Its job is comparing who’s in front of you with faces you recall from the past. All of this happens in a billionth of a second and is under the radar, so we don’t realize how biased our judgment is when we meet a new person, making bigots and sexist pigs of us all. So if I meet a slightly obese, older woman with dyed red hair and wire-rimmed glasses, I will probably be hostile because my grandmother looked like that and always took out her false teeth in front of my friends. This poor woman won’t know why I’m treating her like a leper.

The whole brain works as a unit to keep you alive. Isn’t that heartwarming? Someone cares. You. Each of these parts of your brain individually wouldn’t know what to do and would be just a lump of uselessness but all together they are more complex than the universe and beyond. (See Star Trek.)

If, say, you’re walking in the jungle and there’s a curvy thing on the ground. In the first few tenths of a second light bounces off the curvy thing and is sent to the occipital cortex where it’s registered, then for further processing the image is sent to the hippocampus (the filing cabinet) to evaluate if it’s a threat or an opportunity. If the hippocampus gets a slight feeling this squiggly thing could be dangerous, it sends out a “jump-now-check-later” message, which informs the amygdala, which in turn rings the alarm, “Emergency, emergency.” This warning notifies your fight-or-flight neural and hormonal systems, and at that point your reproductive and digestive organs shut down because, as I’ve said, the last thing you need to do when you’re about to be obliterated is to eat or procreate. Almost immediately, blood and oxygen drain from your brain to shoot into your arms and legs to get you ready for fight or flight. Your heart speeds up, your breathing accelerates. Your memory and any clear thinking are obliterated because all your glucose and blood have left the building and are heading out to your peripheries.

Meanwhile the slow prefrontal cortex has been yanking information out of long-term memory trying to figure out if it’s a stick or a snake. It may register that no one else around has panicked and, after a few more seconds, access the neurons it needs to fire into the pattern that informs you it’s a stick. How about that for teamwork? Eventually this experience works its way to the language centers but not until much later, so in the height of panic you have no words. It takes about 240 milliseconds for you to even start a grunt. And then let the swearing begin.

How You Developed

Evolution plays its part in creating an experience-dependent brain in that you are born inside out (don’t panic, it all works out) so when you’re only a one-month-old embryo, your outer layer of cells folds inward, forming your brain stem, and this is why our insides were once literally connected to the outside. The DNA instructs the neurons on which area they should migrate to. They then connect to each other, based on your experience, and that ultimately will determine how your brain is shaped. Only the strong and often-used neurons survive, and the rest die off, like sperm that don’t make it through the big swim.

Somehow every single cell has to know if it’s a cell for your nose or part of your toenail and find its way to that particular area. No GPS, no nothing. Can you imagine that kind of a challenge? Trillions of cells trying to put together the puzzle of all your parts; what makes you you. It would be like rush hour, squared. What are the chances that you come out vaguely normal and not looking like a Picasso with three breasts coming out of your forehead? I wouldn’t bet on the odds. And let’s say you form the full complement of limbs and digits and a brain that works; now you depend on your parents (two descendants of a one-celled amoeba) to fill your tiny empty brain with the first spoonfuls of knowledge; teaching you to talk, walk, think, feel, flirt, and freak out. This is why each of us, each generation, has to struggle with this universal quandary: What are we supposed to be doing here?

How Our Brains Grow

Reptiles lay some eggs or just stand and deliver and move on; without sentimentality they walk away to mate again somewhere with anyone who happens to be mounting them at the time while they’re munching on some lawn. Then the baby automatically knows how to swim, slither, trot, or fly away. We are born knowing nothing and just lie there in our own mess till someone lifts us out of it and bothers to change our pants. They (animals) need no manual, they just know things. Compared to other primates, humans are born far too early for their brain to be mature. (If we could stay in our mother’s womb for the brain to fully develop we’d be in there twenty-four months.) The only reason we come out at nine months is because our heads wouldn’t fit through the birth canal if we stayed in there and would end up doing some serious damage to Mommy; she would probably never walk again and sue us for personal injury. You know that scene in Ben-Hur where they tie each of a man’s legs to an elephant and then scream, “Giddy up?” That’s how Mommy would feel.

The genes build the scaffolding of your head in-vitro but once outside Baby has only his basic amphibian brain, just enough to keep his heart and breathing going and that’s about all. But it’s not all bad news. Evolution can be smart sometimes, and because we come out so undercooked the development of our brain depends on external experience. We have so much to learn once we’re out so we need that external stimuli to develop, which is a blessing because it would be impossible to learn shorthand or Ping-Pong while we’re inside the womb. This is a very clever idea because no one knows where you’re going to be born, and you need different skills depending on the area and culture you plop out into. If you’re born in the Sahara, it would be good to have a structure that would make you proficient in camel straddling or if you’re born in New York, it’s more helpful if you develop the motor skills to honk and scream at other drivers. We have so much learning to do. (This is called neural Darwinism.)

By age three, the baby’s brain has formed about a thousand trillion synaptic connections. At that point, the baby has the equipment to speak any language in the world. Its ears, tongue, and mouth are primed for any sound or accent that may be needed depending on where it’s born. The sounds around you shape your tongue and palate, so the first sixteen months will determine your accent. If you’re German, you will probably make that sound in your throat that sounds like you’re about to bring up phlegm.

Before you learn to speak, your brain is like a wad of chewing gum so any language is possible to learn with the perfect accompanying accent, and unless you become an impressionist, you’ll be stuck with it. You better learn fast at this point because after the first two months half your neurons drop dead.

The right hemisphere has a higher rate of growth during the first eighteen months, which establishes the basic structures of attachment and emotional regulation. During the second year of life, a growth spurt happens in the left hemisphere. We learn to crawl, then walk, and then there’s an explosion of language skills such as saying “poo, poo.” The hands and eyes become more connected to visual stimuli and vocabulary develops, so now we can demand things like a rattle on ice with a splash of vermouth. The language areas are activated by about eighteen months after birth and babies begin to develop self-consciousness, recognizing themselves in a mirror. This is the birth of the concept of “I” when you get that feeling that you are you, if you know what I mean.

As Baby matures, neural circuits, guided by the environment, connect. As sensory systems develop, they provide increasingly precise input to shape neural network formation and more and more complex patterns of behavior. Now Baby can draw like Rembrandt. Movements and emotional networks connect with motor systems so you can spit in someone’s face because they have pissed you off. Now all the wires of behavior, movement, sensory experience, and emotions connect and feed each other information, like wires in a complex phone system. Right and left hemisphere integration allows us to put feelings into words. This linking up of right and left hemispheres is accomplished through Mommy and Baby eye contact, facial expressions and speaking “goo goo,” which is called “motherese.” (Some single women use it with their cats.) The baby imitates Mommy and so he or she learns how to put feelings into words. Then when Mommy rocks the baby, her hormones are released, making baby feel safe. A game of peek-a-boo activates the baby’s nervous system by the fine art of surprise and leads to cascades of biological processes enhancing Baby’s excitement. Peek-a-boo is not just an aimless activity, it is a brain grower. So forget chess and sudoku; just jump out at someone from behind a door—you’ll be doing them a big favor, upping their IQ by thousands.

The memory of how Mommy is with Baby influences the baby’s physiology, biology, neurology, and psychology. How the brain grows is affected by how she put you down, held, smiled, ignored, or forgot you; she is the uber-regulator, the big boss of brain development. The neural clusters for social and emotional learning are sculpted by Mommy’s attunement with Baby. She grows these neurons in the baby by making direct eye contact with her left eye to Baby’s right eye. This is why Mommies usually hold babies in their left arm so this eye contact is made easier. When they gaze into each other’s eyes, their hearts, brains, and minds are linking up. These face-to-face interactions increase oxygen consumption and energy. Also, holding the baby in this position means it can hear Mommy’s heartbeat. Seeing her loving face looking down on Baby triggers high levels of endogenous opiates so he experiences pleasure in later social interactions by the positive and exciting stimulation from Mommy.

Babies are built to engage and respond to the world.

If the mother is too connected, this affects Baby and later he might feel people are encroaching on his space. If, on the other hand, she is too disconnected, he might in later life feel abandoned and become a comedian looking for constant attention. If the mother soothes the terrified baby, he learns to regulate his own fear. The mother’s face shows him what is safe and what isn’t. If she shows fear or any negative state, the baby internalizes it. If she expresses depression or shows an expressionless face, the baby, not being able to think something is wrong with the mother, believes he is the cause and so has a greater chance of having depression or some other mental dysfunction himself, while keeping an idealized image of his caretaker; his survival depends on her. Babies are built to engage and respond to the world. If they don’t get a response, they stop engaging with the world and can become emotionally frozen.

The holding and separating that are repeated by mother and child help the baby to self-regulate throughout his life while he learns how to care for himself. When the mother over-holds you can soon see the results; every Jewish boy’s first novel is about mothers who never let go.

Neuroplasticity

As I said right at the beginning of this book, it was thought about ten years ago that, gene-wise, you’re hardwired from birth; imprisoned by your DNA. But now science has broken that shackle; change is possible well into old age. It was thanks to a scientist named Michael Meaney that the idea of genetic determinism was toppled like the Berlin Wall; here one day, gone the next. His experiments on rats showed that the way a mother treats her babies determines which genes in the offspring’s brains are turned on and which are turned off, demonstrating that the genes we’re born with are simply nature’s opening shot. If maternal behavior changes, the genes change. Fearful baby rats were put with nurturing mother rats and were licked rather than ignored and their actual genetic expression changed, proving we’re not held captive by our genes. (I wouldn’t have wanted my mother to lick me but perhaps it would have made me more positive and loving. Who am I to say?)

All this applies to humans in that if you inherit genes that give you a more aggressive, depressive, or anxious nature but if your life, especially your early life, exposes you to empathetic people, those negative genes may never be expressed and their makeup altered.

The brain changes continuously by every sight, sound, taste, touch, thought, and feeling.

As I lead you into Part 4, I just want to remind you that the brain changes continuously by every sight, sound, taste, touch, thought, and feeling. Experience and learning remodel new circuits (neurogenesis).

We do know some of our ingredients and what they do, and maybe in years to come we’ll be able to carry around some kind of recipe that will allow us to change who we are day by day. We might decide we want to take a tablespoon of oxytocin and dribble in some dopamine to make us feel good about finishing our homework.

But for right now, the practice of mindfulness gives you some of the utensils that help you turn something you burned and destroyed into something that tastes good and feels soothing inside.

ONE LAST THING

Before I move on to Part 4, I just want to bring your attention to how misguided we are in insisting the external world is exactly as we see it. Much of what you see out there is manufactured by your brain, painted in like computer-generated graphics in a movie; only a very small part of the inputs to your occipital lobe comes directly from the external world. The rest comes from internal memory stores and other processes. Think of the area in your visual cortex, a projection room creating what’s out there from incoming information. In actuality we see the world in single snapshots, and it is a part of your brain that makes it seem like it’s constantly moving. There are about seventy separate areas working to create a cohesive picture of the world; one part contributes color, another movement, another edges, another picks up shapes and another shadows. There is no single part that gets the whole picture. And in completely different zones, the images get a name, or an association or an emotional tag.

Sorry to be the bearer of bad news again; we live in a virtual reality. Think of The Wizard of Oz—you’re being run by the guy behind the curtain. You get clips that randomly come into your consciousness—never the whole film. So while you’re getting these fleeting clips to make you feel that’s all that’s going on, a trillion things without you knowing it are going on right now inside you.

When you wake up in the morning, you remember who you were the day before because of billions of neurons, electrically zapping around the brain, working around the clock to make you believe you have unity and keep you wanting to exist.

Another thing your remarkable brain is doing is keeping your heart beating more than a hundred thousand times per day. That’s forty million heartbeats per year, pumping two gallons of blood per minute, through a system of vascular channels about sixty thousand miles in length or twice the circumference of the Earth. Should I go on? (Skip the rest of this if it gets too much.) Just now a hundred thousand chemical reactions took place in every single one of your cells. Multiply those hundred thousand chemical reactions by the seventy to hundred trillion cells that make up you. (I couldn’t do that but maybe you can.) So while your body’s doing its thing, you could be using your mind to bring you calm and happiness. What a segue to introduce you to mindfulness.