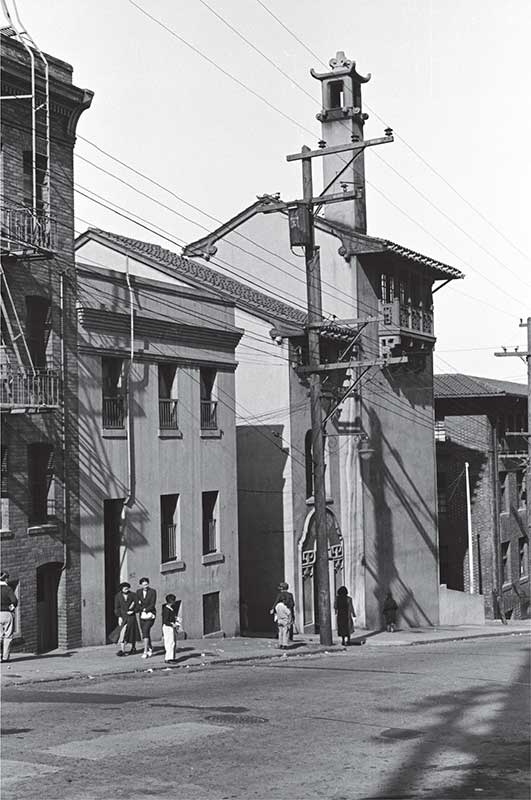

Former entrance to the Chinese Hospital, where many Chinatown kids were born. The entrance was removed when the hospital was remodeled. Photo by author.

1

DUAL CULTURES AND IDENTITY

“I WAS TOTALLY CONFUSED”

By the late 1950s and early ’60s, many postwar ABCs were reaching their teen years. Approaching or already in junior high or high school, their cultural orientation and national identification had gravitated strongly toward those of mainstream America. A great number of these ABCs had already begun to lose fluency in their parents’ and grandparents’ native Chinese. Outside of school, the media—radio, television, cinema, popular magazines and daily newspapers—pushed them even further away from the “old country” and its ways and into the broad embrace of the United States. There were fun and innocent things associated with America: Mickey Mouse, sock hops, hula hoops and rock ’n’ roll. There were also darker things: teen angst, identity crises and racial ambiguity. For no small number of the ABCs, the matters of race and identity that first entered their consciousness during childhood remained to be figured out into their college and post-college years and beyond.

STILL A BIT DIFFERENT

“Our Physical Appearance Could Not Be Hidden or Denied”

A former Chinatown kid, now well over sixty years old and retired, looked back at who he was and what he thought he might one day become.

Former entrance to the Chinese Hospital, where many Chinatown kids were born. The entrance was removed when the hospital was remodeled. Photo by author.

My father came over from China when he was eighteen years old. My mother, however, was an ABC. Except for my paternal grandparents, there was nobody from my father’s side of the family to have much influence on me. Of the people I grew up with in and around Chinatown, some, like me, had one ABC parent and one born in China. Others had both parents being ABC, and there were still others whose mother and father were both born in China.

I mention this because I think that having an ABC parent made me feel a little more American and less Chinese than some of my friends and schoolmates might have. We never talked about it that I can remember, but I always thought that I could tell which of the people my age that I knew tended to be “more Chinese” or “more American.” I very strongly identified with the most typical American childhood heroes of television and the comics: Roy Rogers, Superman, Hopalong Cassidy, Dick Tracy and others. None were Chinese, of course. I didn’t think too deeply about it as a child, but I innately sensed that they and I were different and that maybe I wouldn’t grow up to be a detective or a cowboy.

Baby boom! Nurse with a baby in the Chinese Hospital nursery, October 1949. Eight other newborns are visible. Author’s collection.

Television shows had some Chinese characters, but I never cared for any of them. There was a butler character on the situation comedy Bachelor Father and a cook on the Western drama Bonanza. A Walt Disney series that I liked about teenaged pals Spin and Marty at summer camp also had a Chinese cook. My paternal grandfather was a cook and butler (houseboy), and my maternal grandfather was a cook as well. I never saw them in the same way that I saw the characters on television. I hated the TV guys. I was embarrassed by them. They were portrayed as silly at best and outright stupid at worst.

I remember one day when I was listening to a Giants baseball game on the radio, and I was just sitting by the radio while tossing a baseball up and down. My father walked by and said, “Ah! There he is! The Chinese Willie Mays!” I was flattered that my dad would acknowledge me like that, but I knew very well that there were no Chinese major-league players. Playing ball with friends at the North Beach Playground, we would sometimes announce to each other, “I’m Mickey Mantle!” or “I’m Stan Musial!” It was what we felt and even what we believed, but our physical appearance could not be hidden or denied. Major-league baseball and a lot of other things probably weren’t going to be for any of us. For my part, I suppressed that reality, but I still rarely deviated from feeling more American than Chinese.

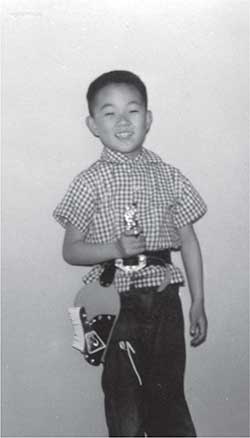

Inspired by his Wild West heroes, a seven-year-old cowboy brandishes his trusty six-shooter. Author’s collection.

Irene Dea Collier did not speak any English when she was brought to San Francisco by her parents at the age of five. She learned quickly, however, and she was soon often taken for ABC by her friends and schoolmates. She remembered a part of the quintessential rite of passage of becoming a teenager: “We had in the 1950s Chinese American teenagers becoming just American teenagers. In Chinatown we had Topps Fountain, we had the Chinese owned and operated soda fountain Fong-Fong. We had kids running around in purple jackets and slicked-back hair looking like Elvis Presley.”1

THE CULTURAL DIVIDE

“We’re Chinese and You’re Chinese-American”

Shawn Wong was born of immigrant parents in the United States. The family lived in Berkeley, and Shawn was familiar with San Francisco’s Chinatown of the 1950s and ’60s. Because Shawn’s father worked for the U.S. military, the family frequently had to move from base to base both within the United States and abroad. Shawn’s schoolmates and friends often were other dependents of civilians contracted to the armed forces or the children of military personnel. Few of these other children were Chinese. Shawn said:

My mother used to tell me, “We’re Chinese and you’re Chinese-American.” I had no idea what that was. I didn’t know what the difference was. My mother would wear Chinese dresses—cheung-sam. My mother and father would speak Chinese to each other at home and, here I am, this little boy who wanted to be Willie Mays. I wanted to be Roy Rogers, “The King of the Cowboys.” I didn’t think of myself as being Chinese; I thought of myself as being just like any other American kid. I think I just had to figure it out on my own. Your parents are always telling you, “Be proud you’re Chinese,” you know and, of course, yeah, yeah, right, Mom! That doesn’t help me out in the schoolyard.2

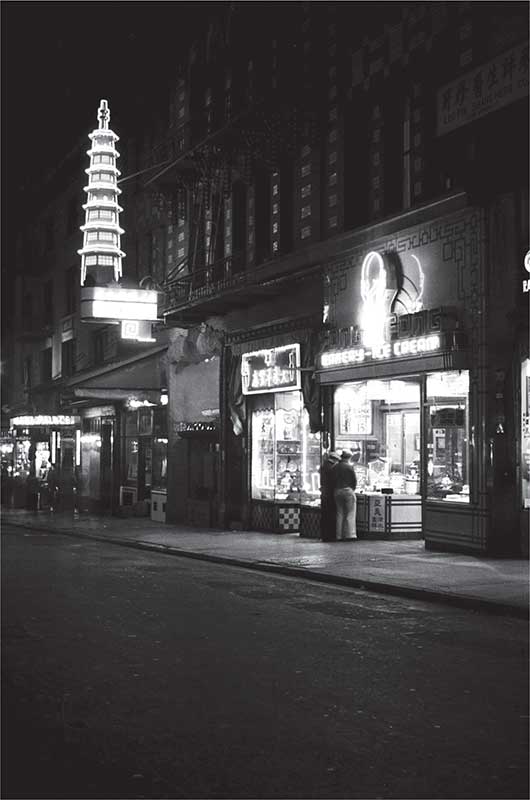

Fong-Fong (1935–1974) offered burgers, hotdogs, Cokes and ice cream, which included “Chinese” flavors such as ginger and lychee. Ken Cathcart Collection. Courtesy of Schein and Schein.

GROWING AWARENESS

“It Was Racial, Right?”

As Chinatown’s kids became old enough to understand movies, those films that were to make the deepest impressions on them were the ones aimed at the teenaged audience. One such film was West Side Story. Based on an original Broadway production from 1957, the film version came out in 1961. It was a national success and won ten Academy Awards. It was as wildly popular in San Francisco Chinatown as it was anywhere else in the United States. The story was an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet set in modern times. The plot featured ethnically divided teen groups, young love and racial tensions, represented by a rivalry between the groups and a star-crossed attempt at interracial romance.

The themes and the more serious undercurrents represented by the film were not lost on its young Chinese American viewers. Brad Lum of San Francisco’s Chinatown said: “It [the movie] was racial, right? Puerto Rican against White. It was kind of what we had to relate with. It was the ‘Sharks’ against the ‘Jets.’”3

Reverend Norman Fong remembered going to see West Side Story a total of six times:

We always walked out of there snapping our fingers [as the actors had done in one of the film’s featured dance sequences] thinking that we’re tough and “we bad.” The sixties was turmoil everywhere in the world, but for us Chinatown kids it was life shattering. We had to go [to schools outside of Chinatown] and we faced racism for the first time. Growing up in Chinatown everyone’s Chinese; everyone knows each other and then all of a sudden we realized that other people did not like the Chinese. I’m proud to be Chinese; I’m not embarrassed; I’m not ashamed. Maybe my parents’ generation had to be, they were beat on too much. But for me; I’m born here, the next generation; I’m not gonna take it. After West Side Story and all those movies, everybody learned. Sometimes you have to organize and fight back, then they leave you alone.4

Norman described a personal experience linked to his fervent notions about “not just taking it” and “organizing and fighting back.” One day, while just a grade-school student, Norman felt that his teacher was labeling or belittling the Chinese, and he chose to speak out.

I went to Jean Parker [for grade school] where all the kids are Chinese but the principal and the teachers were all white. For me it was a time of racism. I got in trouble in the fifth grade. The teacher was making fun of the Chinese and I said, “Shut up!” to the teacher. So in the fifth grade I got expelled from school because I told the teacher to shut up. She was saying that the Chinese were good cooks and laundry people. Now, my dad was a cook, by the way, but I felt there was a little bit of a misunderstanding about why the Chinese ended up in those areas. So I said, “Shut up!” My mom was head of the PTA so it was very embarrassing. I felt that racism was a key issue in the 50s and the 60s. The Chinese community was not really that well respected.5

Years later, Norman would be able to smile about this incident as he witnessed the student outcry and strike at San Francisco State College for substantive and more truthful representation of the Chinese and other minority races in higher education.

BILINGUALISM AT ITS CHILDISH WORST

Mrs. Horse Shit

Despite their youth and the sheltered community in which they lived, Chinatown’s kids harbored a few of their own cultural insensitivities toward the adults who ran the schools they attended.

Although practically all Chinatown kids grew up fully bilingual in Toishan Chinese and English, many were quick to lose their Chinese language skills once they began to attend school. Some originally spoke only Chinese at home, while others used both languages. In a home where the family could speak either English or Chinese, it was not unusual to hear words from both languages intermingled within a single sentence, such as “Nay tai movie, sic mut snacks, ah?” for “What snacks did you have (earlier) at the movies?” When among friends and classmates, the youngsters’ preferred language was always English. With each passing year, the ABCs’ Chinese skills would become increasingly diminished. Still, the language, however little or however imperfectly retained, was something that would never fully disappear. One Chinatown ABC remembers some dual-language fun from his days at Washington Irving School in the 1950s.

Washington Irving third grade, 1957. The two boys at the lower right are the class’s only non-Chinese students. Author’s collection.

The average kid knows practically all the swear words he is ever going to use as an adult by the time he starts school. Bilingual kids have the advantage of knowing duplicate sets of such vocabulary. There is one word that may or may not actually be a “bad” word in Chinese, although it certainly is in English. The Toishan version of it roughly bears the tone of the western musical note of E or “mi” of “do re mi” and is pronounced “see.” “See” spoken as the note E in Toishan Chinese means “shit.” It was the context of using “see” in a conversation that determined if it was acceptable or not. If talking matter-of-factly about having or not having gone to the bathroom, it was alright. It was also proper to report that while visiting the zoo, one had seen a monkey sitting in a pile of it. It was perfectly fine and even a little bit funny to say something like, “The baby’s diaper was full of it and, boy, did it smell awful.” It would be a far different and impolite matter, however, to suggest that someone should go and eat some of it.

At Washington Irving, my K–6 school, we American-born Chinese very much enjoyed wordplay with “see.” There was a teacher of Italian descent named Mrs. Lagomarsino who had no real faults except, unknown to any Italians, her name. And this was only in the minds of young Chinese American school kids. We would call her “Lago-MA-SEE-no” when she was out of sight with great stress on the middle two syllables. “Ma,” in a certain tone not duplicated by the musical scale, is a horse. So, behind her back, she was “Mrs. Horse Shit.” Then there was the principal, a fearsome man of huge proportions to whose office we would never wish to be sent. His name was Mr. Orsini. We very privately referred to him as “Mr. OR-SEE-ni.” With the “see” part clear, the “or” made it a verb, as in to make some or to take one.

Another Washington Irving teacher was Miss Fotinos. Her Greek name provided us with no opportunities to degrade it by blending it phonetically with Chinese. We would probably not have done so, anyhow. She was one of the school’s kindest and most popular teachers. Still, that did not stop our clever little minds from having some good laughs at her expense.

One afternoon, during a geography lesson, Miss Fotinos was helping us locate and identify various bodies of water on a map. “Here, between Africa and the Middle East lies the Red Sea,” she said, tapping the appropriate spot with a pointer. This was instantly and simultaneously translated by thirty little minds as “red shit.” Thirty little voices exploded with laughter. “What’s so funny?” asked our totally perplexed teacher. The fact that she had expressed puzzlement made it all the more hilarious to us. More laughter. “Come on!” she urged, “what’s the big joke?” Seeing that our hilarity had not spoiled her overall tendency of being good-natured merely egged us on even further.

The laughter eventually stopped, but knowing a thing or two about geography, we sat on the edge of our seats and braced ourselves. “Well, here in the Mediterranean,” and she left it at that to our disappointment, “is Sicily, where the still-active volcano Mount Etna can be found.” Miss Fotinos paused, let her eyes sweep the room and then visibly relaxed. “Now up here, further north,” we got ready for it, “by Russia, is the Black Sea.” If not from Etna, an eruption nonetheless ensued. “What’s going on!?” Unabated hilarity. Tap, tap, tap! The pointer hit the nearby blackboard. “C’mon, tell me!” We stopped cold. Tell her? We looked at one another as if to ask, “Are you gonna tell her, cuz I’m not!” We sat still and tried to hide our smiles as we wiped tears from our eyes and bit our lips. We were feeling a little sorry for Miss Fotinos. “May I continue, please?” she asked. “Yes, Miss Fotinos,” we contritely replied. It would not be for a few days before we worked our way across the Pacific to the Yellow Sea.

FURTHER MISADVENTURES FOR NORMAN FONG

“Let’s Get the Chinaman!”

Two years after the incident at Jean Parker, Norman Fong was assigned to attend Francisco Junior High School, one of the places that he earlier described as a “school outside of Chinatown.” Francisco was within walking distance of Chinatown, but being in North Beach, it was in the midst of a residential area populated by many Italian Americans. The following experience between Norman and a group of Catholic school students who were about the same age as him left its mark on the seventh-grade Chinese American boy.

While I was in junior high I got in trouble with the Italians who didn’t like the Chinese. I got beat up. My first day going to Francisco Junior High, which is in North Beach, I remember walking across Washington Square [a public park directly across the street from Saint Peter and Paul Catholic Church and the Salesian Boy’s School]. I was a happy kid in Chinatown, right? The world is all Chinese then you gotta go to North Beach. I meet the Salesian boys as I’m walking by and they tied me to a fence and said, “Let’s get the Chinaman!” So they water balloon tortured me…can you imagine those water bombs? Wham! Wham! Wham! And I got so angry. That was my first introduction to racism.

There was a movement in North Beach: D.A.C. for Damn All Chinamen. “D.A.C.” was spray-painted all over North Beach Playground. And I got beat up a few times by those boys just because I’m walking alone, which is not that smart.6

LOOKING TO FIT IN

American Enough or Chinese Enough?

Racial confrontations such as those described by Norman and even more severe ones were not the only source of emotional (or physical) growing pains with which Chinatown kids had to wrestle. There was also the confusion that often led to frustration about their sense of self. As a youngster, Norman Fong’s good friend Tommy Lim had once said that he “hated” being Chinese and that all he really craved was to “fit in.” Retired CPA Ron Jung had said of his first day of school that his was the “only foreign face” in the entire classroom. Even to the present day, he remains uncertain if he is “American enough” or “Chinese enough.”

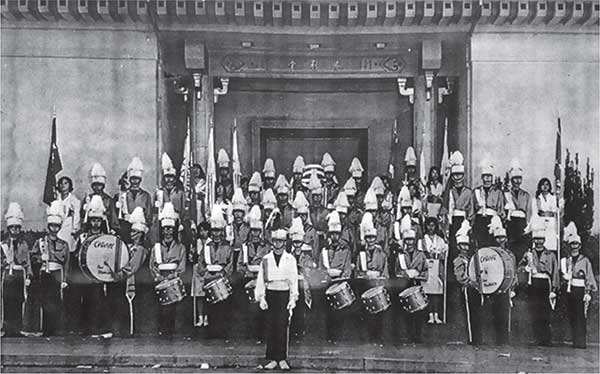

Prewar American Legion Cathay Post Drum and Bugle Corps. The photo includes five relatives of fourth-generation ABC Steve Tong. Courtesy of Steve Tong.

The Cathay Post Drum and Bugle Corps updated to “all-American” uniforms in 1963. Courtesy of Jack Woo.

Referring to how he viewed himself as an adolescent, Norman said: “I was probably totally confused. Because of the split culture. I guess because, you know, speak English only in the morning (at school); speak Chinese only in the late afternoon (in Chinese school or at home).”7

The arrival of the relatively novel martial-arts genre of Chinese films in Chinatown’s theaters in the early 1960s brought considerable relief to many of Chinatown’s identity-challenged adolescents. Television and comic books, wildly popular in Chinatown as anywhere else, were bereft of any Chinese characters (or others who bore Asian features) that were not buffoons or villains. This was especially clear in the case of post–World War II comics, in which exaggeratedly caricaturized “Japs” were often depicted as “rats” or “yellow skinned monkeys.”

These films from Hong Kong and Taiwan, often set in historical times, were replete with attractive costumes and sets. The plots were typically straightforward demonstrations of right against wrong, but the films were far more fast-paced and action-packed than their closest American counterpart, the Western. The always handsome or pretty Chinese good guys, as likely to be a female heroine as a man, bravely and fiercely confronted foes in fantastically choreographed scenes. The battles, fought barehanded or with swords, never failed to include superhuman flips, twists and circus-like acrobatics. The more fantastic human feats included special effects that provided actors with the ability to run across water, leap backward over rooftops or snatch flying poisoned darts out of the air.

Chinese Central High School class photo, 1965. Back row, right: future California state senator Leland Yee. Courtesy of Jack Woo.

Jack Woo in his Chinese school marching band. Jack says he enjoyed the band far more than he did classes. Courtesy of Jack Woo.

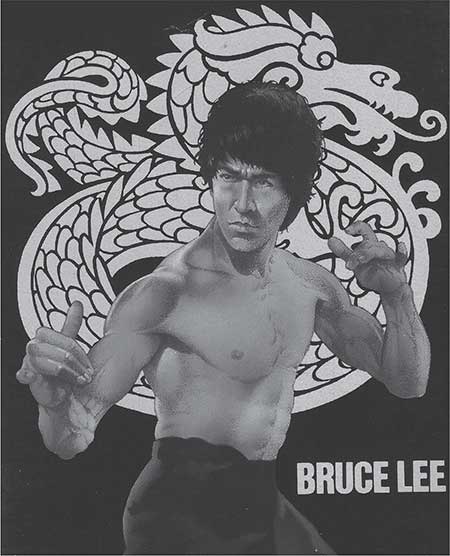

The films offered more than a momentary escape from reality. They provided a morale-boosting glimpse of self-worth and individual potential. Norman Fong and his friends began to see themselves in a more positive light. “On the English side you don’t see any Chinese-American heroes. Not one. And then on the other side, go to Chinese movies and see Gung-fu stars.8 It was good that I had some role models.”9

According to Brad Lum, Chinatown boys began to sign up for kung fu training because they had finally found heroes like themselves that they could emulate: “The sword fighting epics came to Chinatown. That’s when we all got hooked and went down to the Sun Sing and Great Star. And we all signed up to learn Kung-fu at that time. That really kind of brought it [our sense of self] up a notch. Eight-Eighty. It was just an address [for the kung fu studio founded by grandmaster Wong Jack Man at 880 Pacific Avenue] and it wasn’t the name of a gang but that’s what ended up happening: they called us the ‘Eight-Eighty Boys.’”10

Norman Fong, one of the 880 Boys, added:

All of us kids hung out here at the 880. This is where we made pretend that we were Gung-fu stars. Friday nights, you could see everybody here. Maybe a hundred guys. And then sometimes we would come out here [onto the sidewalks in front of or just beyond the studio] to practice…just practicing you know? And sometimes we would even fight each other and sometimes it would even hurt, man! Eight-Eighties; it was fun! It was guys hanging out and we feel good about ourselves.11

The self-affirmation motivated by the films did not affect only boys. Looking back to her younger days living in Chinatown, Amy Chung remembered being amazed and impressed at seeing Chinese persons portraying roles that had hitherto been absent in her life. “Dragon Inn, I think it was called in English and it was really the precursor to all those Gung-fu movies.12 And what really impressed me was the fact that the hero to this movie was female. She was amazing. Little toughie.”13

Film star Bruce Lee. Other Chinatown film role models included Cheng Pei Pei, Ivy Ling Po, Jimmy Wang Yu and David Chiang. By author from VHS box art.

Many of the martial-arts film actors, whether male or female, also appeared in films set in modern times. These included romances, dramas and musicals. Amy spoke about how she felt the influence of some of her favorite actresses when they performed in films set in the current times:

Living in Chinatown you were kind of on the fringe; you weren’t really mainstream. What I remember from [actresses] Jiang Pui Pui and Siu Fong Fong was that they were people I could relate to. With the go-go boots and the A-line skirts and the hip-huggers; that whole generation of [Chinatown] teenagers emulated those [Chinese film] girls. Obviously we all had that kind of clothes, but you never quite look like everybody else [who were not Chinese] at school. I mean, obviously we would never look like Twiggy or Penelope Tree [popular British fashion models of the 1960s]. Seeing somebody dressed in A-line skirts and acting very independent and apparently cool; it just spoke to us.14

PURPOSE AND DIRECTION

“An Ethnic Awakening”

Irene Dea Collier is now happily retired from a long career as a middle school social studies teacher in the San Francisco school district. As a teacher, she was a strong advocate for a more ethnically accurate and inclusive school curriculum and a voice for the protection of minority teachers’ rights. Irene recalled the onset of the ’70s, when most of Chinatown’s baby boomers had already finished high school:

When we went to college, there was suddenly an ethnic awakening. Everyone wanted to find out who they were. And we had to just figure it out.

For me, an accumulation of things might have surged into my conscious mind at the time. The way I was once told that I did “not belong” at the Woolworth’s lunch counter when I was twelve, or the way some of our high school teachers looked down on us for being Chinese, or the lousy wages my mother got for making highly priced clothing that was sold in big-name downtown department stores all sort of kept nagging at me.

A friend once said that he thought I was always a sort of quiet or timid sort of person. I don’t think that’s true. I think that I’ve always expressed myself freely and openly. Even when I was a child back in our village in China, I would run around barefoot and scream as loudly as I could about things I didn’t like. The village ladies all knew who I was for it, too.15

Despite being retired, Irene keeps busy. She has said that she wants to “slow down.” But in the very same breath, she adds, “But my conscience rises up to say that I need to do useful things. I should continue to contribute.” Irene recently took a break from working on a middle school reading list that she wants to make more inclusive, with titles by Asian American authors, to reflect on a lifetime of striving to be a force for positive community improvement, growth and development.

In college, I participated in the strikes at San Francisco State. Among the things that we wanted were courses that were inclusive and accurate in depicting all the things that non-European immigrants did to help get our country to where it is today. I had been in a class on the history of immigration where a classmate and friend asked the professor, “What can you tell us about the contributions of the Chinese to America?” The response was that they were “not significant.” We were angered, irritated and just thoroughly pissed at that. Eventually, the administration paid enough attention to our insistence that it offer courses on Asian American studies, Latino or Chicano studies and “black studies.” “Black studies” are now African American studies. The first of these courses were poorly organized and taught by people who weren’t really professors, but eventually they improved and became a part of the accredited curriculum.

After I graduated, I got credentialed and went into teaching. It wasn’t long before I saw a need for more non-Anglo teachers in the city’s system. I mean, where was there any balance in such a multicultural city as San Francisco when the majority of schoolteachers were white? Furthermore, whenever the budget needed trimming, the nonwhite teachers were always the first ones to be let go. Since it was the ’70s, they were typically recent hires and the old policy of “last hired, first fired” was used to justify their dismissals. As a member and later as the president of the Association of Chinese Teachers, or TACT, I fought against anything like that. I went before the board of supervisors and argued that these teachers, no matter that they were the most recently hired, filled specific needs that would go unfulfilled without them. They were retained. I also pushed for dual-language programs and more ethnically inclusive reading lists. I fought against Muni’s attempt to raise bus fares for students from a quarter per ride to seventy-five cents. A lot of kids in the schools live in poorer neighborhoods. I myself wasn’t so far removed from that very situation. A dollar and a half every day to get to school and back would have been a major financial strain on struggling families.16

FROM STRIKER TO ASSOCIATE DEAN

“By Any Means Necessary!”

Like Irene, Laureen Chew was a student at San Francisco State during the 1968–69 student strike. Although she had entered college as a quiet, somewhat naive girl still in her teens, Laureen was harboring past resentments that were soon to bloom. Increased awareness and sensitivities to the needs of their communities caused disparate groups of students—ABCs from Chinatown, members of the black and Hispanic communities and Native Americans, among others—to coalesce on campus to voice their concerns. Speaking in 2007 from her on-campus office and as the associate dean of the College of Ethnic Studies, Laureen looked back to her student days, when the cry across campus was, “On strike! Shut it down!”

We were many groups that formed the (broader) Third World Liberation Front, so there were different student groups; so I was part of one group. The organization evolves because different individuals got involved with TWLF…and then…they all needed their own individual group to be responsive to. I think that the main thing people forget was that the activities were not only on campus, but also off campus. Academia at that point didn’t have anything that we now call community service learning, community involvement so many of the students found it to be our responsibility to be connected with the community as well as with the campus.

The strike didn’t happen until I was about a junior. I had befriended another Chinese American girl who started to go to organizational meetings with the Black students and then the other Third World students. Then she goes, “You gotta come with us!” And I go, “No!” Of course, I went and we did have many similar experiences in the sense of a cross ethnic group.

My father had a business in Chinatown. And then it all came together in my mind. I had noticed that any time a white customer had a problem in Chinatown with the way we did our job…especially in the family laundry when my father was in the front they would say things like, “Oh, you stupid Chinaman! You lost my sock again! What the ‘f ’ is wrong with you people?” And I didn’t understand. My father’s reaction to it was really weird; he was like “Hahaha! Yeah, I’m so sorry!” He would just kind of laugh it off. And I’m in the back folding the laundry and getting like pissed off ! I wanted to say something. I couldn’t because I didn’t know what to say.

Once we were ready to strike the saying was, “By any means necessary.” It’s a very Maoist saying. Many of us were Maoist ’cuz it was time to be a Maoist and to be a communist and to be anything out of the ordinary, especially the right or the middle; we were totally the left. We were labelled radical for nothing. I mean, I didn’t care. My mother would have cared; my father would have killed us. But me? We really didn’t care what the consequences were.17

Once the strikes were at their height, law enforcement was brought onto campus and things got heated. Laureen remembers:

I don’t know where all these cops came from. They had the Tac Squad… horses…they just surrounded us. I know this guy, he was a friend of mine, and he was three persons in front of me and they just started swinging their batons. I saw his head get bashed and it was horrific. I almost passed out! I was screaming, “Get him outta there!” I was trying to pull him in, but it was people on top of people. It was horrible. That bloodshed that day. I just don’t understand how those people could do that. But they did. And we stood there for hours waiting to get booked and put in the paddy wagon for downtown.18

Laureen found herself at the downtown jail along with hundreds of her fellow protestors. She continues to express disappointment that her belief in truth and accuracy on the part of the government or the media was glaringly absent when events as she saw and understood them were at best not reported at all and at worst misrepresented.

The day we got busted they took us down to Bryant Street. There were 400 people there, except the men and the women were on different floors. And when we were in there, people were still protesting. They were screaming, “On strike! Shut it down!” The whole building shook. Well, before I knew it they were trying to quiet us down. First, they shot a gun to scare us, but it was shot in the air so it didn’t scare us and we kept on yelling. I didn’t because I was like, “Forget it.” The next thing I know I was sitting on a bench and this huge blast of water knocked me from my seat up against the wall. Certain women had their arms and legs broken. I was totally wet and scared.

And so we decided to hold a press conference the next day. And every channel came.19 We told our side of the story as to how mistreated we were. And it was cruel to have seen people get hurt like that. And I was like, “Finally! They’re going to tell our side of the story on TV.” Later when I was out of jail I turned on every channel. Well, they had very little except CBS, Channel 5. And they had the Sherriff’s Department come on and that was the only thing they showed. Not our side of the story. Well, the Sheriff ’s Department said that these women were defecating on the floor and we did not use high pressure hoses, we used garden hoses to clean it up. And no one was hurt. The only people that recorded it accurately was KQED.20

Mark Zannini had many good and close ABC friends from Francisco and Galileo who introduced him to their activities, experiences, families and homes in or near Chinatown. Mark relished the opportunity to learn about and take part in the things that his ABC friends liked. While he did not take more than an observer’s role in any of the Asian American activist movements of the late 1960s and early ’70s, he nonetheless felt that he had gotten close enough to them to want to offer his thoughts from those years.

I believe that our Galileo graduating class of January 1966 was, in my own words, “The Last of the Squares.” We had in Chinatown what I relate to as a version of the experience depicted in the film, American Graffiti. Ours, I felt, was to be the last time high school and graduation would feel as it did in the era prior to the revolutionary ’60s. I had many friends in the graduating class that followed mine in June of 1966 who were already starting to reflect the cultural changes that came with the rise of the Hippie movement in San Francisco: colorful clothes, changing hair-dos, Peace buttons on their jackets. However, pictures of our class in the 1965 yearbook show barely a trace of Beatle haircuts or mod clothes—especially among the ABCs. Styles were either tending towards “getting ready to grow up and go to college and on to marriage and business” or “still hanging in the hood, working at the gas station and playing pool.” There were small hints that some in our class might embrace aspects of the coming revolution that included the response to the Vietnam War, recreational and at times dangerous drug use, and the Women’s Lib movement. Another cultural trend that was to affect my friends from Chinatown was the practice of “shacking up”—living together without getting married. This was shocking enough in middle class White America but in Chinatown it was a huge challenge to people whose cultural history practically equates family to religion. Some in my class who were going steady married in one or two years after high school but much fewer in comparison with the period just a few years before.

In the next three years I would see and experience a cultural revolution in Chinatown that was both similar and quite different from what was happening in San Francisco at large and the nation as a whole. In Chinatown the influence of what the Black Panthers were doing was felt in the establishment of activist groups such as the Leeways and the Kearny Street Workshop. Alex Hing and others started the Red Guard which was an even more flagrant and radical cultural response. Reactions to the Vietnam War ranged from open anti-war attitudes to young men who acted patriotically by volunteering in the military. Drug use was becoming common; casual marijuana and some experimentation with psychedelics, but also street drugs such as Quaaludes and tranquilizers were having their effects. Rising ethnic pride and the popularity of Bruce Lee brought Chinese martial arts out of the cultural closet and into the public consciousness and established a new image of masculinity. The classic Mao jacket and cloth gung fu shoes became common items of garb. The image of Chinese Americans as seen by the broader public was being transformed from the too long-held stereotypes of inscrutability, subservience and deviousness portrayed in Hollywood movies. Other popular as well as the seemingly positive clichés were also being altered: not all ABCs were studious and obedient sons and daughters. My ABC friends were finding themselves and living lives independent of their families and the old traditions that had been with them since they were born.21

A majority of Chinatown’s high schoolers graduated from Galileo (viewed from Polk Street). Inspired by its namesake, the school has its own observatory. Photo by author.

PRESERVING THE CHINATOWN COMMUNITY

Organizing and Fighting Back

Since the days of his youthful struggles, Norman Fong has become a highly respected figure throughout Chinatown, and he has lived by his own words to organize and “fight back.” Norman’s has been a responsible and reasonable voice that advocates for his Chinese community. Over the past thirty years, Norman has remained in Chinatown, where he has been creating youth programs, working in neighborhood planning and empowerment and advocating for affordable housing. He is also the present-day executive director of the Chinatown Community Development Center (CCDC).

Norman became interested in community service early in his life. As a youngster, he was familiar with Cameron House and the Presbyterian Church in Chinatown. Like many generations of Chinatown residents before and after him, Norman participated in many of the Chinatown-oriented youth activities offered by Cameron House: sports, arts, camping and carnivals. He also understood that Cameron House was an organization dedicated to support and benefit the Chinese American community that surrounded it.

When he was a boy, Norman’s family lived on the very edge of Chinatown. One day, the building occupied by the Fongs was sold. The family was evicted, and none of its members had the least idea about what to do or where to go. Cameron House stepped up to their assistance, and so did the Presbyterian Church. They helped with temporary shelter and supplied basic services until their resettlement efforts met success. The abundance of kindness and support given to him and his family made a lasting impression on Norman.

As a way of repayment, young Norman volunteered to help with the Cameron House and Presbyterian Church community outreach activities. He participated in a food delivery program to people living in Chinatown single-room-occupancy tenements. These places were, and remain, perpetually crowded, dark and insalubrious. The tenants have to share kitchens and bathrooms that are down the hall from their rooms. Norman continued to work with Cameron House throughout his high school years and ultimately became day camp director.

Currently a parish associate with the Presbyterian Church, Norman has undertaken the support of the current Chinatown community as his primary life’s goal. He said: “My mother was American born, and my father came through the immigration station on Angel Island. My mother was born in 1919, and she lived her entire life in Chinatown. When she was older, I promised her that I would always do all that I could to preserve her neighborhood and help make it a good place to live.”22

Cameron House (far left) was a fun place with games, sports, carnivals, camping, leadership skills and spiritual growth. Ken Cathcart Collection. Courtesy of Schein and Schein.

Amy Chung, another ABC from Chinatown, has also been active with the Chinatown Development Center. Her background in law and real estate helped her spend over two decades as a vice chair for International Hotel Senior Housing, Inc., where she concentrated on resisting the forces of neighborhood gentrification that would have displaced many of Chinatown’s residents and businesses. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, the original International Hotel on Kearny Street became the focal point of a landmark struggle for fair and affordable housing in Chinatown.

The hotel had been standing since 1909. By the mid-1960s, it was one of the few places that the city’s aging and mostly male Filipino population could call home or neighborhood. Practically all of what had once been Manilatown, the Filipino equivalent to neighboring Chinatown, had been bought, bulldozed and rebuilt as part of San Francisco’s Financial District. Residents feared that similar encroachments into Chinatown would not be long in coming.

The final outpost of the once-thriving Filipino American community was sold and slated for demolition. Investors purchased the I-Hotel in 1968, and two years later, a former executive director of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency was quoted as saying, “This land is too valuable to let poor people park on it.” The almost two hundred residents were given notices of eviction. Asian American students at UC Berkeley and SF State were galvanized by the type of ethnic awakening mentioned by Irene Dea Collier. Many of these students had enrolled in the Asian American studies courses created in the aftermath of the 1968–69 strikes at San Francisco State. They rekindled their involvement with the campus-based Third World Liberation Front. The principle most strongly espoused by both coursework and the Front was that of returning to one’s community to work and, if need be, fight for justice. The cry of “Save the I-Hotel” was born, and as Irene Dea Collier said, many of the young Asian Americans seeking further and deeper meaning in their cultural origins took action. Protests and demonstrations led to court fights that tied up the eviction and demolition process for years. Finally, in August 1977, police broke through a cordon of vociferous protestors to enact the long-delayed evictions.

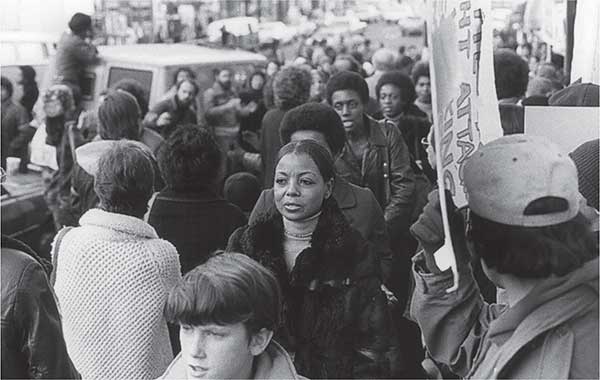

Heightened social awareness throughout Chinatown led to protests against the eviction of International Hotel residents in 1970. Getty Images.

The building was soon demolished. The Chinatown kids of the 1950s and ’60s who had organized, fought and gave no small measure back to the community that fostered them were ultimately rewarded, however. A new International Hotel was completed some quarter of a century after the demise of the original. The current hotel, built in partnership with the Archdiocese of San Francisco and the community, includes slightly over one hundred units of affordable senior housing and became the new location of Saint Mary’s Catholic School, which had been formerly located on Stockton Street.

Recently, Norman Fong very likely echoed the pride and sense of accomplishment of many when, standing in Portsmouth Square (in the neighborhood’s heart), he spoke about Chinatown: “This square is where it all began. The Chinese community fought to save this neighborhood and it’s the first Chinatown in the whole country. This is where Asian Americans began. Right here!”23

Norman’s ongoing youth-oriented programs at the CCDC have included alleyway renovation and beautification and hands-on support efforts for the elderly and economically disadvantaged. Still, neither Norman nor Amy nor any number of former Chinatown kids has any illusions about the future of their old home and neighborhood. While it is far less family oriented than it was in the 1950s and ’60s, it still remains densely populated, with an estimated seventeen thousand residents, about 50 percent of whom live in cramped single-room quarters reminiscent of those of the old International Hotel. The fight to keep rents affordable will continue in the face of pressures from the ever-expanding and neighboring Financial District.

Norman spoke for more than a few when he emphatically offered the following statement: “I love serving my home community of Chinatown and San Francisco!”24

The American Planning Association named Chinatown as “One of the ten great neighborhoods in America.” The APA, a nonprofit organization, says that its mission is to advocate “excellence in planning, promoting education and citizen empowerment, and providing our members with the tools and support necessary to meet the challenges of growth and change.”

A LITTLE MORE ON IDENTITY

“This Is Me!”

Parents usually spent weekdays at work, so it was both convenient and logical that grandma should help out. Quite a few of Chinatown’s kids were reared by a grandmother who grounded them in the ways and traditions of China. Some of their own children have been likewise nurtured by a grandmother. Ngin-ngin is the thlay yip (say yup) variant of Toishan Chinese for paternal grandmother, while paw-paw refers to the maternal grandmother.

One former Chinatown kid who was born at the Chinese Hospital was cared for by his ngin-ngin, who watched after him for about a year before he was old enough to start school. He remembers that his grandmother’s daily conversations with him, along with some of her more fantastic stories, taught him how to speak Toishan Chinese fluently. This same grandmother taught him how to write a little in Chinese.

My grandmother showed me how to write in Chinese. She taught me quite a few of the basic words, among them man, woman, good, big, mountain, gold and the numbers from one to ten. These characters were fairly easy for me because the most challenging one only consists of six strokes of the brush, pencil or pen. Chinese characters can be learned by memorizing the order of each of the strokes required to create them. If she had been able to spend more time with me, I am certain that I would have learned a great many more characters. I would not be able to spell “mountain”—an easy three-stroke Chinese character—in English for another two to three years.

The youngster’s grandmother entertained him with many stories in Chinese.

One of my grandmother’s stories was a scary one about an evil dragon. She said that when she was little the family home and those all around it was tormented by a huge and mean dragon. People would not go out at night because they were afraid. The dragon had eaten some people, and nobody wanted to be its next victim. One day, according to my grandmother, she was out walking on the nearby mountain. She heard noises around the bend, and when she turned the corner, there stood the dragon. My grandmother began to cry and she shut her eyes. She had some oranges with her, however, and she held one out at arm’s length with her eyes still closed tight. She felt a powerful rush of wind and thought she had just been eaten. She stood still for a long time and finally opened her eyes. The dragon was gone. Nobody saw him again, but whenever there was an earthquake, everyone knew that it was the dragon twisting and turning in his underground lair.

It was a great story for me as a child. I told it to my own daughter when she was at that age when sitting on Dad’s lap for a story was so much fun for her. I told it in English, of course. I could never, no matter how hard I try, tell it in Chinese. My grandmother was a huge early influence on me, and I remember her with great fondness. I feel badly sometimes that I let the things about China that she talked so lovingly about just become irrelevant to me in my life as an American.

Sherry Pang is a fifth-generation Chinese American and native San Franciscan. Happily married and with two grown children, Sherry talked about being Chinese or Chinese American:

When my children were young they stayed with their paternal grandma during the day. She spoke to them in Chinese. I think my son still understands quite a bit but he has to answer her in English most of the time. In our own home we don’t do very many traditional Chinese things and I don’t know how to make the different foods that are part of the Lunar New Year celebrations.

Grandma doesn’t force her traditions on us or the grandchildren, but there are certain things she would ask us to do, like visit the cemetery on the appropriate dates for the honoring of ancestors. If she asks us once and the answer is no, she won’t pursue it. We generally go because she doesn’t ask that much of us and it makes us happy to be able to take her.

Cake, ice cream and an American-style birthday celebration, 1952. Author’s collection.

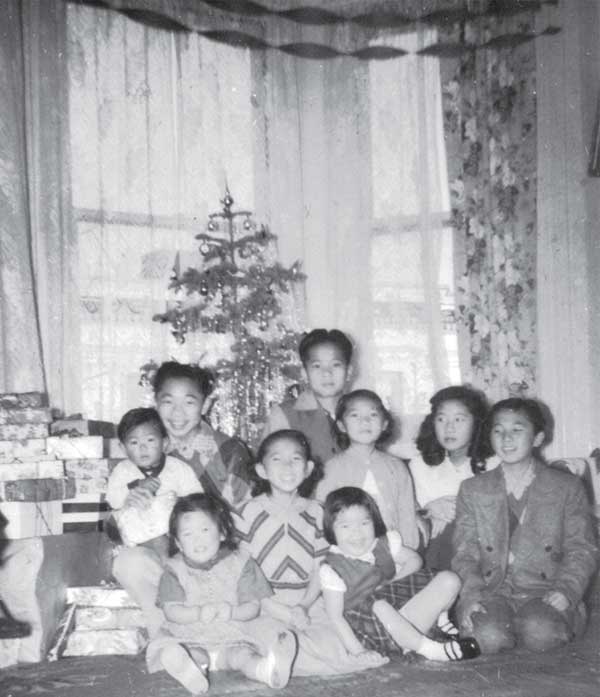

Christmas with gifts from Santa at Grandfather’s Chinatown flat, 1949. Author’s collection.

It doesn’t bother me that we are not traditional Chinese. If we eat Chinese food at home, my husband is the one who makes it or we bring it over from grandma’s house. When I ask my son what he thinks we ought to do when he gets married, he says that we should have a Chinese banquet because we’re Chinese. Sometimes I feel we are floating in the middle between being Chinese and being American, but on a personal level, this is not a problem for me.25

Cecilia Wong comes across as being very much Americanized as she expresses herself with considerable certainty about her feelings: “I have a new boyfriend now and he’s Chinese. And I was over at his apartment and I opened the (kitchen) cabinet and inside is fish sauce, and soy sauce, and he had oyster sauce. I suddenly felt like, ‘This is me!’ I feel comfortable. This is what I want. My ex-boyfriend; he had baked beans and ketchup in his cabinet. And I eat those things as well, but it’s just different. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life with half of me missing.”26