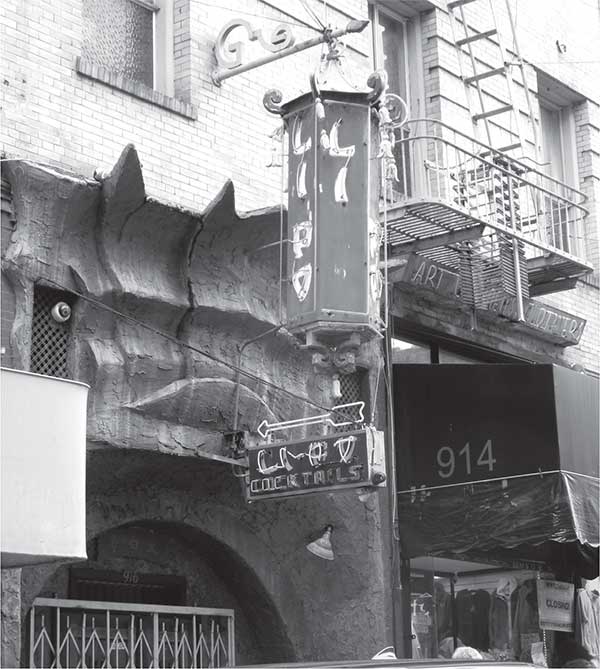

The Li Po bar has been around since the 1930s. Travel Channel star Anthony Bourdain recently fell in love with its famous mai tai. Photo by author.

3

THE LONELINESS OF BEING GAY

“I COULD HAVE BEEN A DUTIFUL CHINESE SON AND FAKED IT”

Darryl Eng was born in 1947 at San Francisco’s Chinese Hospital.42 His family lived in various locations within easy walking distance of Chinatown, and his father at one time or another owned several small businesses there. His mother was an ABC, as was the majority of her side of the family. Although he was born in China, Darryl’s father arrived in San Francisco at a very early age and remained in the city for the rest of his life. Practically all of Darryl’s older relatives on his father’s side were born in China. His family spoke the thlay yip dialect of the Toishan area of China.

Although Chinese was spoken frequently in Darryl’s home, his parents never talked about China. According to Darryl, his father never even talked about his own father, who was a prominent figure back in China and who was also the founder of one of Chinatown’s community newspapers, the Young China. Of his father, Darryl said:

My dad had an orchard near Isleton in Sacramento County, which is where one of his uncles had a tomato cannery. Some of my aunts on Mom’s side would go to work at the facility during the summer canning season to help out and to get away from the city for a while. I heard this sort of information through the talk of aunts and uncles. I wasn’t close to my parents, and there was never very much that was shared to me by either of them. One thing about them is that they were “anti-Chinatown,” which I think is odd, because we shopped there, ate out a lot there and my father made regular rounds there as a wholesale liquor sales representative.

The Li Po bar has been around since the 1930s. Travel Channel star Anthony Bourdain recently fell in love with its famous mai tai. Photo by author.

After starting school, Darryl began to turn completely away from things Chinese. He had quickly observed that English rather than Chinese was to be the language of choice and that American history, culture and values were the norm. He quickly adapted. It was not long before he favored hot dogs over the traditional Chinese sausage lop cheung, sometimes called the “Chinese hot dog” by many ABCs of the time. Darryl also preferred to see himself as a cowboy hero like television’s Roy Rogers or Hopalong Cassidy far more readily than as Wong Fei-Hung, the martial-arts champion of the oppressed seen almost weekly in the Chinatown movie houses. Darryl even openly rebelled against the Chinese lessons he was sent to take.

I went for lessons from Dung Seen Sang, who had been a teacher in one of Chinatown’s regular Chinese schools. She offered the lessons in a lobby space within her apartment building that was located on Montgomery Street just off of Broadway. This building of single-occupancy rooms was not luxurious or fancy, but it was far nicer than a lot of similar places found in Chinatown. There were several others in the class. Our parents had chosen Dung Seen Sang because she was willing to teach us in our own village dialect of thlay yip. The regular Chinese schools taught in Cantonese (and eventually in Mandarin), which would have been difficult and confusing for us.43

Chinese Central High School, Jung Wah Hok Hau and the Chinese Six Companies. This is a former 1970s Chinatown anti-bussing “Freedom School.” Photo by author.

So, there we would be at her building to take lessons in the basics of speaking, reading and writing. While she spoke in our family dialect, which we understood perfectly well, we were just, as they say nowadays, “not that into it.” I remember once when we gently unscrewed the light bulbs of our study area so that when she turned the switch on there was no light. We fed off one another, and we began to do this somewhat regularly. The reward was that she would be totally perplexed and cancel class. Another time, we climbed up to the roof and were playing around when we were spotted by someone’s mother who lived nearby. She reported us all to our respective parents, and boy, did we get it!

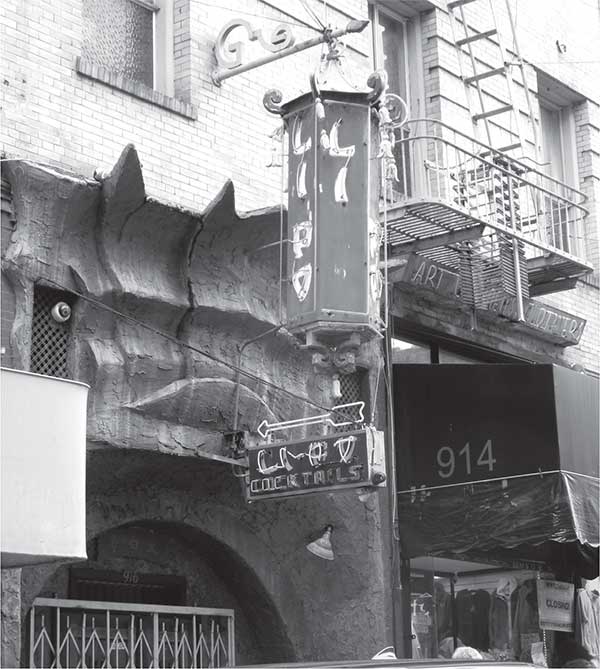

Chinese school instructional chart. Reciting loudly pleased the teachers, even if not everyone understood what they were shouting. Ken Cathcart Collection. Courtesy of Schein and Schein.

This sort of thing went on for close to a year. We sometimes actually sat through our poor teacher’s lessons and behaved, but other times we were unruly enough to put her completely out of sorts. Eventually one set of parents decided that they were wasting their money, and all the rest followed suit. So much for learning Chinese!

CIRCLING BACK

“I Needed Something…an Identity”

Over the years, however, Darryl has become the “most Chinese” of all his siblings and cousins. He has relearned the language, which he speaks very well, and he is thoroughly knowledgeable about his family’s native cuisine, traditions and customs. His renewed grasp of his heritage has so impressed his cousins that they often call on him for advice or assistance with things like recipes, Chinese New Year celebrations, red egg and ginger parties, wedding practices, bai sun and more.

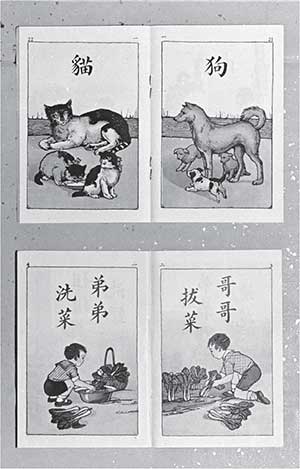

Up on the roof. Mom’s laundry and flower garden, Dad’s chicken and pigeon roosts, kids’ play space. Ken Cathcart Collection. Courtesy of Schein and Schein.

Darryl’s return to his roots began in his late teens or early twenties. The journey was certainly in full bloom by the early 1970s, when Darryl landed a job with the State of California not long after finishing his time in the army. He was now in a position of sufficient financial stability to begin what has become a lifelong passion: collecting Chinese art and antiques. In addition to the reconnection to his past, Darryl has said that his collection of quality items, all well studied and researched, was to serve as an investment for the future. Darryl’s plan was that if ever he should need money in later life, he would be able to sell items from his collection. Now retired, Darryl’s home is filled with impressive and beautiful Chinese antiques and decor. The home is very well appointed, and most of his furnishings fully serve for the daily functioning of his household rather than to merely grace the premises as objets d’art as in a museum.

Darryl characterizes his collection as follows: “I do have good Chinese things in the house. Only a few of my pieces are museum quality, a few are close to museum quality and the rest are just quality. I have a scroll with a Chinese lady painted onto it and a vase that I was told bears Ming markings that are museum quality. Some of my items that are close to museum quality include a set of chairs and several bowls or vases.”

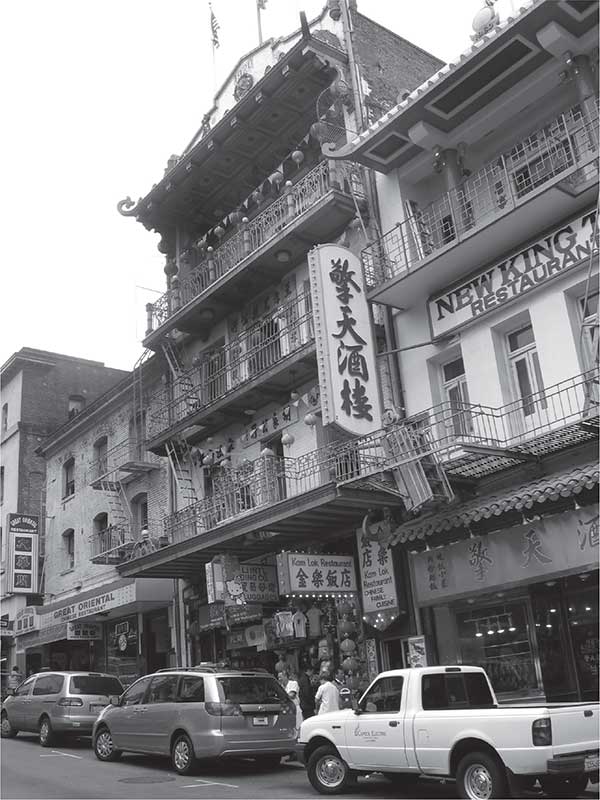

Waverly Place, one of Chinatown’s busiest and most colorful alleyways. Photo by author.

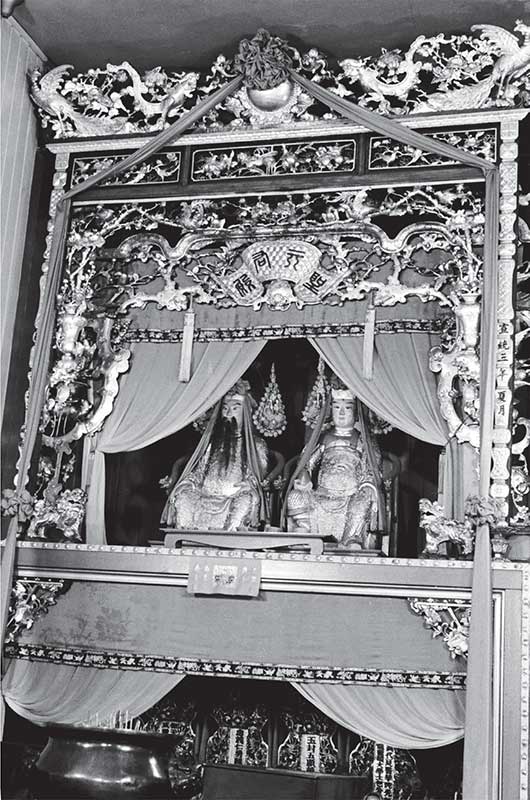

Interior of a Chinatown temple. Possibly Tin Hau (“Empress of Heaven”) Temple in Waverly Street, founded in 1852. Ken Cathcart Collection. Courtesy of Schein and Schein.

Darryl adds that the following list of items would have been earmarked for sale had a bad financial situation befallen him.

Ivory carving held onto by Darryl Eng as “an investment for the future.” Photo by author.

Some of the good quality things include two sets of rice bowls that are late nineteenth century, a zodiac set that is porcelain/ceramic and some bowls or vases. They were a nice investment in that I paid fairly little for them and over time they have increased a lot in value. I could also have sold some scrolls, Chinese opera gowns or rugs. On top of all that, I also bought gold jewelry years ago, and I have at least a pound’s worth of it scattered in various hiding places around the house. I’m retired now and I’m financially secure, so I don’t have to think about pawning anything to raise money anymore.

With no apparent need for any form of financial liquidation, Darryl has instead begun to slowly gift items from his household to the younger members of his family as a legacy of their original culture.

THINGS NOT UNDERSTOOD

“I Felt Alone and Unwanted and Unloved”

Darryl explained the path of his eventual coming full circle from full rebellion to once again embrace what it is to be Chinese. It was a long and at times difficult process.

I think it was in my late teens or early twenties, but I am pretty sure that I really started getting back to being Chinese after I got out of the service. It was in the early ’70s, and I was working for the state in Southern California. Having been born and raised in San Francisco, living near Chinatown and being fairly close to certain cousins and adult family members back there, I was a little out of my element in Southern California. I wasn’t miserable or unhappy, and I was perfectly fine at work, but I would come back often to San Francisco to visit relatives or to take part in birthdays or Chinese New Year celebrations and things like that.

Of course, I needed a place to stay whenever I came to the city. My mom had passed away in the mid-1960s, and my father’s was just not a place I wanted to go to. I wound up staying regularly with my Aunt Susan, who was my mother’s eldest sister, and her husband, Uncle Frank. Over time, I became very close to them. They became the parents that I had always craved but never had. I remember as a child, going to see the Disney movie Cinderella, and as I watched it, I felt alone and unwanted and unloved just like she did. I asked myself if I weren’t adopted, and all through it, I just kept thinking that I must be just like that little girl [Cinderella].

The problem with my parents was that by the time I was eight years old my mother noticed that I was showing signs and behaviors of gayness. This was a real blow to her. At that time, it was illegal to be gay. On top of that, as a boy, the automatic and unshakeable expectation was for me to produce a son. Not only would my parents be blessed with a grandson, but there would be an heir to the family name and fortune. Well, since I actually am gay, there wasn’t going to be any chance of that. While the failure to live up to those expectations was mine, Chinese culture places the burdens of a son’s shortcomings fully upon the parents. I, therefore, had brought shame and disgrace to all. I suppose, in afterthought, I could have been a dutiful Chinese son and faked it. I could have gotten married, sired a son and then have a gay lover on the sly.

Well, going back in time to my childhood, I was only eight and had no idea whatsoever that I was being anything [other] than my normal self. My parents were not long in turning their backs on me. Many years later, I asked one of my aunts why she thought my parents didn’t love me. She astounded me by telling me that, faced with the possibility of me being gay, my mother had considered sending me for the type of electroshock treatments that in those days were believed to be curative.

Washington Street has long been home to many specialty shops and restaurants serving Chinatown’s residents. Photo by author.

ON BEING CHINESE AND BEING HAPPY

“Uncle Frank and Aunt Susan Didn’t Care about Any of That”

Well, Uncle Frank and Aunt Susan didn’t care about any of that. They were welcoming, accepting and loving. They have since passed, but I will always cherish and honor their memories. Over my numerous short-term stays with them, I gradually began to gravitate more toward the Chinese culture. Aunt Susan was an ABC, and Uncle Frank was born in China, but he was a World War II veteran who had landed at Normandy for the D-day invasion in 1944. Nonetheless, they were really very traditionally Chinese. Their house was furnished and decorated in a Chinese style, and they always cooked Chinese food. Uncle Frank was the cook, and he was really good at it. Of course, while visiting them I couldn’t let myself just sit in the kitchen talking and not offer to help. I gradually went from doing the simple things like washing rice or cutting veggies to learning Uncle Frank’s techniques and recipes. Through all the cooking and talking about this and that, I also began to absorb more of the language. Uncle Frank spoke sam yup, and Aunt Susan spoke thlay yip, so that was interesting and fun. The two dialects aren’t all that different, but they’re different enough. Of course, I also began to pick up on traditions, holidays, celebrations and all that sort of thing.

Uncle Frank and Aunt Susan liked to host the entire family for a big Chinese New Year celebration every year. Over time, and as they got a bit older and slower, I learned enough to make bigger and better contributions to the effort. It really was a lot of fun for me, and of course, the warmth, closeness and joy that I experienced with Uncle Frank and Aunt Susan just meant so much to me. I have carried on their tradition since their passing, and I think I do it as much as an honor to them as I do for the significance of New Year itself. I do love having the family over for it, but I’m getting older myself, so I may only do it for another year or so.

There was still something missing, however. I was gay, and I certainly couldn’t go around showing that part of me. I am not in the least bit ashamed of it now, of course, but my upbringing was certainly not what led me to my current conclusions and feelings. Not only had I been an “outlaw” for it, but my own family had ostracized me because of it. I also began to feel less strongly American as I might have at one time. After all, there was my physical appearance. I look fully Chinese. There is no white in me at all. Furthermore, I couldn’t help but resent the type of discrimination and racism that so many of my forbearers had had to endure. One of my uncles used to tell me stories about how Chinatown residents could not step foot beyond the boundaries of their neighborhood. To venture beyond Broadway Street, for example, invited violence, and there was not going to be any police intervention against it.

So who was I and what was I? I needed something. I needed an identity. Being Chinese is what I chose. I look in the mirror and that is absolutely what I am. And I think about my dear Aunt Susan and Uncle Frank. Uncle Frank actually condemned my father’s attitudes and behaviors toward me. So, I love them forever, and all that they were to me and all that they showed me that was Chinese is what I have happily chosen to be.

Still, I do not believe in every single thing that is Chinese. I pick and choose. I mainly do what I like and just let what I don’t like go. It’s time for me to be myself and to do what makes me happy. Take the matter of bai sun, honoring one’s ancestors, for example. My parents used to make me do it in the springtime, which was when my birthday is. Imagine, celebrating a child’s birthday at a cemetery! Well, I don’t do bai sun for anyone except for Aunt Susan and Uncle Frank. And I make sure to bring fresh flowers to them whenever I am in town. They deserve it, and I will love, cherish and honor them in the traditional way until I myself die.