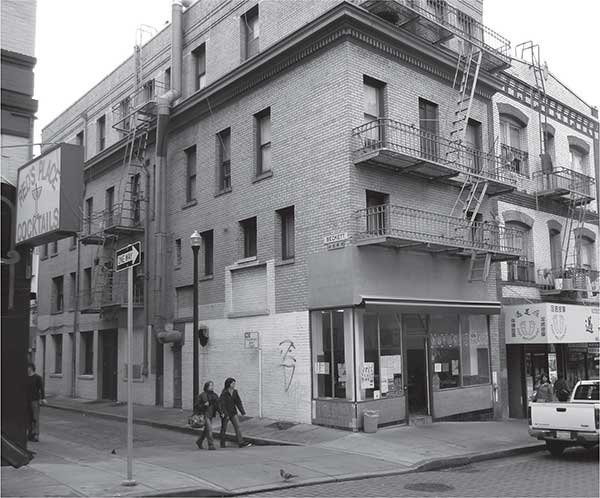

Standby dishes continue to warm the hearts of old Chinatown kids to the present day. Photo by author.

6

HOME COOKING, RESTAURANTS AND TAKEOUT

GREAT MEMORIES OF YUMMY FOOD AND LOVE

Late hours at work might not have allowed every family member to be present for the evening meal, but in Chinatown, the call to dinner was the time of family togetherness. Whether the meal was taken in relative silence as mandated by the father or if it was fairly open with kids and adults chattering away simultaneously, there was a feeling of family unity at the table. The sense of community was heightened by the fact that food was shared. Dishes were set in the middle of the table, and diners reached for what they wanted when they wanted it. Sometimes, a family member would use his or her chopsticks to helpfully place something onto another’s plate or rice bowl. It was face-to-face time, and nobody read a newspaper or listened to a radio or tried to sneak a peek at the TV. The TV or radio would have been turned off, anyway.

A FEW OF OUR LEAST FAVORITE THINGS

Green Milk and White Gobs

Growing up, each Chinatown baby boomer had food that was his or her favorite. There were also those items that were less than favorites. The list of what the Chinatown boomers did not enjoy eating, while not extensive, reflects the general childhood aversion to vegetables. One such out-of-favor vegetable (although not true for everyone) was foo gwa, the bitter melon.

Standby dishes continue to warm the hearts of old Chinatown kids to the present day. Photo by author.

The foo gwa is roughly the size and shape of a cucumber, but it is a much brighter green, and the thick and waxy outer skin is wrinkled or ridged. It was most frequently slit open, scraped clean of seeds and sectioned to be stir-fried or made into soup. Melody Chan Doss-Wambeke, who grew up at the foot of Telegraph Hill in North Beach, still shudders a bit when recalling the melon’s taste: “Of course, our least favorite dish was probably the healthiest one for us: sautéed bitter melon! Mom made it often with beef and black bean sauce. The sauce helped a lot, but no matter how it was cooked it always lived up to its name and stayed bitter!”78

Jack Woo, a retired pharmacist, stated:

My least favorite food as a kid was bitter melon. Gradually, though, as I got older it became my favorite. I guess it was because Mom just kept cooking it and I somehow developed a taste for it. Now I always order it when I visit Chinatown. Another favorite when I was a kid was cow brains in soup. I don’t eat it anymore, though. Cholesterol! My go to comfort food during high school and college was hom-yue gee-yuk beng. It’s made by mincing a piece of pork butt with a cleaver, spreading it as a thin patty onto a platter, placing some dried salt fish in the middle of the diced meat and steaming it all. Put it over rice and…yummmmm…it really gets your appetite going.79

Many who eat bitter melon agree with Jack and say that it is an acquired taste.

While none has nearly as strong a taste as foo gwa, the following have a place on the childhood list of least favorites: broccoli, green beans, spinach and various Chinese choy, or green leafy vegetables.

While saying nothing about his own preferences, a former schoolteacher remembered a childhood episode involving his younger brother and some stir-fried gai lan choy. Although it is a leafy green, it is sometimes called “Chinese broccoli,” because its flavor is supposedly similar to that of broccoli.

My brother was about six years old at the time, and we were at the dinner table. Dad was at work, so it was me, my brother and sister and my mother. The rule was that we were all to stay at the table until everyone was finished. Usually it wasn’t a problem. Well, that night, my brother decided that he just didn’t like stir-fried gai lan choy and refused to eat it. My mother gave him the spiel that, until he did, we would just sit at the table and wait.

My brother picked some of the gai lan up and dipped it into his milk. My mother said that she didn’t care what he did with it; he was still going to have to eat it. I was irritated because I wanted to go watch TV, but the sight of my brother’s milk turning green made me laugh. That made my mother snap at me to be still. My brother continued to hand dip his gai lan choy into his milk. Our mother glared at him and said that he was also going to have to drink all his milk as well. My brother continued dipping and dunking his gai lan. Green-tinged milk was splattering all over the table. Finally, our mother decided that enough was enough, and she started shoving soppy gai lan into my brother’s mouth and holding her hand against his lips so that he had to swallow. I was bursting with laughter, and my eyes were so watery that I couldn’t see. Finally, my mother said that she had had enough and we should all just get out of her sight.

A graduate of Galileo High and former special education teacher remembers her moments with a food that she found to be less than savory: “I remember the only food that I could not eat as a kid was these white gobs of flour in a soup. I’m not quite sure what you call them! We had them once at my grandma’s with my cousins. We couldn’t chew them and we couldn’t swallow them whole. Spitting them out would have been gross and someone might come by to make us eat them anyhow. So we tossed them out the window. Needless to say the street outside grandma’s apartment was covered with all these big white splotches that we thought looked a lot like giant pigeon droppings!”80

GIRLS JUST WANT TO HAVE FUN

“I Got Some to Stick on the Ceiling”

Some may find a dislike for bok choy surprising, since the leafy green has found its way to popularity in many stores and markets across America.

Once disdainful of her veggies, Nanette Lim said: “I chewed my bok choy, but I couldn’t swallow it. I would spit it out and play with it. Then I would try to see how high I could toss it. I got some to stick on the ceiling. This was when I was in early grade school.”81

In another case of “I just know what I like and what I don’t like,” another now-grown Chinatown girl agreed with Nanette: “Bok choy was the worst!” She recalled that it was served often and remembered gagging on it as she was forced to swallow it, anyway.

For the most part, Chinatown seafood dishes, whether cooked commercially or at home, are well prepared, nutritious, tasty and well liked. As with any food, however, not everyone living in Chinatown found fish or other table fare taken from a watery habitat completely enjoyable. Among Chinatown’s food for sale were snails. These could usually be found in pans of water set out on the sidewalk. They have been characterized as rubbery in texture and a bit spicy in taste.

One woman recalls an adolescent misadventure with the little mollusks that were called teen law. They were often served at her father’s family association. As a child, she and her friends used to have races to see who could eat the most the fastest. She stated that she once competitively slurped them “until I puked.” She added that, from that point onward, she lost her taste for teen law. An acquaintance recalled the unhappy experience of slurping on a snail, only to get a mouthful of teeny little shells. She, too, lost her taste for teen law.

Another girlhood memory comes from Marilyn King: “I never had a least favorite dish, but the weirdest thing I ever tried to do was unsuccessfully try to smash a fish’s eyeball. My mom told me to stop because some people like to eat it.”82

MORE ON THE WHITE GOBS

“They Were Hard to Chew and They Had a Texture I Can’t Describe”

The mystery gobs such as those once tossed out of grandma’s window were subsequently identified by a one-time Chinatown resident who once helped his mother prepare them.

The white gob stuff was called tong yuen. It was pureed sweet rice that was then drained dry in a porous sack. I remember forming the little balls when I was little. It was a winter item that my mom made with chicken broth, turnip slivers and dried shrimp. She topped the broth off with scallions and parsley. You can also make the sweet version of it with melted down Chinese rock candy.

Us Boomers need to learn the old recipes and hand them down to our kids. Otherwise they and all these stories will just be lost.83

Tong yuen is a type of mochi, a Japanese rice ball that has existed since the pre-Christian era. Among the Chinese of more recent times, it is eaten on the first day of winter as a symbolic means of keeping the body warm. The handmade gobs or balls are dropped into hot chicken broth to be fully cooked. The size of each of the balls depends on the preference of the person making them. Dislike for the little white balls has not been limited to childhood.

One-time state employee Darryl Eng said: “I remember eating some recently that were the size of a meatball. Each one took up the entire space of a Chinese soup spoon. They were pretty hard to chew and they had a texture that I can’t really describe. All I can say is that I didn’t like them as a kid and I don’t like them now. They’re pretty hard to swallow. We called them ‘yawn,’ for ‘round thing[s].’”84

Having grown up as a second-generation ABC whose parents were not much into the more traditional Chinese foods, JuJu Lee recalled her first experience with tong yuen as a newlywed: “About those gobs of flour; my parents were born here, so I never had them. Newly married…I went over to my in-laws and my mother-in-law says, ‘Try this; it’s yummy!’ I put it in my mouth and could not swallow that dough ball. Despite wanting to impress my mother-in-law, I had to spit it out into a napkin while she was not looking. I then fished all the others out of my soup to slyly drop into my hubby’s bowl. The soup by itself was fine.”85

Irene Dea Collier, who learned to cook at an early age by her mother’s side, offered an explanation of the yawn or tong yuen as best she knew:

The yawn are a traditional thing for the winter solstice. The date is never exact, but it’s usually on the twenty-first, twenty-second or twenty-third of December. They are specifically round, because the shape is symbolic of unity. You’re supposed to gather as a family and eat them together. There are all kinds of variations; some are colored, others have bits of filling in them and some are sweetened. There are also different ways you can eat them; singly, as many as you want or a big one followed by some small ones. Chinese history and culture are so long and so diverse that I don’t think there is much in the way of specific rules for yawn anymore. The date is important, and sharing with family is important, but I just keep things simple and make the basic village version that my mother did.86

SOME ENDURING FAVORITES

“Great Memories of Love and Yummy Food”

Large numbers of those who grew up in Chinatown during the 1950s and ’60s will swear that there is nothing in the way of food that they did not like. As adults, they now claim that it was all good but are usually hard-pressed to name any specific favorite. Nonetheless, when asked, memories do not take long to conjure up dishes and foods such as mom’s or grandma’s joong that more than one ABC has called a “Chinese burrito,” homemade rice noodles called fun, New Year’s Monk food called jai and much more.

Sophia Wong remembered the wide, flat rice noodle rolls of her youth: “My favorite as a kid was the steamed cheung fun that my grandmother made from scratch. She would liquefy water soaked rice in the blender and then let the resulting rice liquid slow drip into a bowl. She would then pour a thin layer of it onto an old pie pan and add beef filling (to steam). Great memories of love and yummy food. We kids would all sit in the kitchen and wait for the cheung fun. Oh! My least favorite thing was probably plain tong yuen.”87

Grandma’s jai, prepared to be eaten together with one’s extended family at the start of the Lunar New Year celebration, has also been fondly remembered. While the homemade versions will always be held most firmly in the hearts of those who grew up in Chinatown, the dish has gained popularity and can now be readily found in Chinese vegetarian restaurants.

The name jai is derived from shortening the dish’s name lohan jai, which means “Buddha’s delight.” Since it has been around for a long time and because not every one of the many traditional ingredients is always available, there are many versions of the dish. According to several modern-day chefs:

Eating jai on the first day of the New Year symbolizes purification of the body. In general the ingredients represent good luck. Some have specific attributes. Several such as the black fungus (fat choy), lily buds (jinzhen), and gingko nuts (bai guo) all symbolize wealth as well as good fortune. Additional blessings come from the vegetarian nature of the dish. Since not killing animals is a good deed, the kindness is rewarded by good fortune. Using knives, a tool often used to kill for food on the first day of the New Year, is bad luck. Jai which involves a reasonable amount of cutting or slicing must be prepared beforehand during the old year. It is also a requisite to take extra care not to drop loose ingredients onto the floor while preparing jai unless the plan is not to clean them up. Sweeping a floor on the first day of the New Year is equivalent to sweeping out all of a house’s good fortune.88

Lifetime San Francisco resident Melody Chan Doss-Wambeke remembered a favorite that her mother made: joong (also pronounced and spelled doong). Joong are quantities of rice blended with a variety of ingredients, wrapped in lotus leaves formed into a squarish shape with sharp corners, held together by string and steamed.

My favorite was my mother’s joong. I recall that she spent days combining glutinous sticky rice with finely diced Chinese sausage (lop cheung), salt pork, peanuts, dried shrimp, and other Chinese ingredients that she wrapped in dried leaves (which were sold in long strips in Chinatown produce shops for their specific use as joong wraps). She would make about 40 or 50 of them at a time to distribute to family and friends in the early summer. Of course she had her own secret family ingredients that she added. I have tasted joong from restaurants but they never taste like my mother’s version.89

In some instances, one-time Chinatown kids have tried to make their own versions of a favorite dish that they could no longer find. One difficult-to-locate dish if one lives where there are few other Chinese is Peking duck.

A sampling of favorites once handmade by mom or grandma: joong, dumplings and cheung fun. Photo by author.

Joong: sticky rice, meats, nuts and flavorings wrapped in lotus leaves. Photo by author.

Cookbooks stipulate that the main ingredient be “one fresh whole duck from Chinese Market or poultry shop.” If one is not in a Chinatown, the more realistic option would seem to be “one frozen duck encased in plastic wrap from Kroger or Safeway” followed by the principal instruction, “Allow to thaw.”

One Peking duck lover who relocated to the Midwest missed it so badly that he persuaded his teenaged daughter to collaborate with him on an effort to cook their own. They started with a solidly frozen supermarket bird imported from Canada.

The recipe didn’t look particularly complicated. The main trick, I thought, was to try to be as authentic as possible. We first had to hang the duck to dry in the open air breezes. That really wasn’t so hard; I just put a little noose around the stub of the thawed duck’s neck and let it dangle from a conveniently placed hook under the eaves of my roof. When I sent my daughter to check on it an hour or so into the process, she dashed into the house screaming that it was covered by flies. Sure enough, when I looked, all I could see was a jiggling mass of black slowly twisting at the end of its tether. Not wanting to waste a seven-dollar duck, we shooed and brushed the flies away, brought the duck into the kitchen and rinsed it off. We then took it to the basement, reattached it to a joist and put an oscillating fan nearby. We placed a pan underneath the bird to catch any drippings. There wasn’t any sense inviting roaches or ants. It worked fine, and not a single fly bothered our duck.

Later, while the duck roasted, my daughter took on the task of making the thousand-layer buns that are eaten with it. A large part of the success of the buns comes from the technique more than from the recipe. Whatever recipe she followed worked out very well, as the buns were white, warm, moist and fluffy.

Whole Peking duck made at home and served with hoisin sauce. Photo by author.

CHINESE RESTAURANTS

Good, Cheap, Fast and Portals for Immigration

A Chinese chef recently interviewed on television asked why French cuisine, but not any Chinese equivalent, could often command premium pricing at upscale restaurants. The answer might lie in the fact that, from its earliest origins in the United States, Chinese cooking was not designed to be haute cuisine so much as everyday fare for the common person. A majority of the Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in America were bachelor laborers. Strict immigration restrictions barred Chinese women from entry to the United States. The men worked long and hard hours and, lacking wives who might normally prepare meals for them, resorted to either making their own meals or paying other bachelors to cook for them. The men gradually forged homes in the overcrowded neighborhoods to which they were restricted. With time, these isolated enclaves evolved into self-sufficient communities that included inexpensive and basic eateries. The larger and more vibrant of these communities grew into Chinatowns. The pre–World War II Chinatowns of large cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York and Chicago and in smaller cities throughout the country were not long in being discovered by mostly young and adventurous Americans. These non-Chinese were especially attracted to the inexpensive, exotic, tasty and efficiently prepared Chinatown dishes. They appear to have established the standards by which commercial Chinese food is now generally judged.

One of the reasons there are so many Chinese restaurants, whether in Chinatown, the suburbs or shopping malls and plazas, goes back to the former immigration restrictions placed on Chinese. One of the loopholes in the laws of exclusion was created in 1915. It granted special immigration privileges for merchants. Owners of businesses including export-import firms, laundries and restaurants could later sponsor relatives back in China for legal entry into the United States. In the case of restaurants, there were restrictions that served to block “hole-in-the-wall” or makeshift operations that would only nominally be recognized as restaurants. An aspiring restaurant owner/operator would be granted merchant status only if his establishment could meet specific guidelines defining it as a “high grade” restaurant. These rules, designed to prevent a massive flow of individuals claiming to be restaurateurs, were less than foolproof, and many Chinese found ways around them.

Groups of hopeful immigrants back in China would pool money and send one of the investors or partners to lay the groundwork of setting up a restaurant that met the “high grade” requirement. Over the course of time, each investor-partner would take turns as manager or operator of the business and thereby earn full merchant status. The restaurants could not operate in a vacuum, of course, and they would all eventually establish networks with non-Chinese businesses that ranged from restaurant equipment suppliers to food vendors. The white connections of the Chinese business owners would, as much for the benefit of their own businesses as for the needs of the Chinese, often testify to immigration officials as character witnesses on behalf of hopeful immigrants.

Chinatown’s restaurants served to stimulate the economies of both Toishan in China and in San Francisco and the Bay Area. A fair portion of money earned through restaurant operations was sent back to the villages. It helped to supplement family incomes back in the old country and was often put to use for improvements to the villages in the form of schools, roads or water-distribution systems. Nearer to Chinatown, money made its way into city and county tax coffers as well as onto the ledgers of ancillary businesses in the form of black ink.

In San Francisco of the 1950s and ’60s, there were essentially two types of Chinatown restaurants. Those like Johnny Kan’s on the Grant Avenue thoroughfare catered to tourists and celebrities. Locals would usually frequent places like Kan’s only for special occasions like a wedding or a red egg and ginger celebration that called for a banquet. The everyday eateries that took care of the average Chinatown resident were spotted throughout the neighborhood’s streets and miscellaneous alleys. These were the humbler restaurants that offered modest meals at equally modest prices. Some of the places favored by the locals also hoped to attract tourist dollars. These restaurants and cafés featured standard menus that offered dishes designed to appear to be Chinese for the non-Chinese palate. Stapled to or tucked within these menus would be a mimeographed sheet written in Chinese characters with the day’s real Chinese food.

A PLACE FOR THE OLD-TIMERS

Their Roast Pork Melts in Your Mouth

The New Lun Ting Café at 670 Jackson Street sits directly across Beckett Alley from Red’s Place. Red’s, a bar, and the New Lun Ting, commonly called the Pork Chop House by Chinatown old-timers, are neighborhood landmarks. Longtime residents recognize the two businesses as always having been a part of the community. They are a part of a fading era. In the face of economic and social change, these are the types of places that the Chinatown Community Development Center would like to see preserved. Both have been designated as San Francisco legacy businesses: long-established institutions that contribute to the history and culture of their neighborhood.

CCDC executive director Norman Fong is a regular at the Pork Chop House. Of it, he says:

Chinatown was once a bachelor society, a condition brought about by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Restaurants catered to those single men who were more likely to eat alone than to gather in large family groups at a banquet table. The Pork Chop House is one of the last of that kind of place. Its roast pork brings back memories of food that I can still enjoy today. Their roast pork melts in your mouth. It might cost a fortune somewhere else, but it’s really good old Chinatown food. And it’s been the exact same since I was a kid, and no one knows the secret to their gravy. I used to pay a quarter for the roast pork when I was younger, and it still isn’t that much at eight dollars today.90

One of Chinatown’s legacy businesses: the New Lun Ting Café (called the “Pork Chop House” by faithful regulars). Photo by author.

The Pork Chop House menu is eclectic. It represents a blend of two cultures that epitomizes life in 1950s and ’60s Chinatown with what once was loosely defined as “Chinese-American Food.” Among its 2017 offerings are Thai fried rice with ground meat ($8.25), teriyaki roast pork with onions over rice ($8.95), ham and cheese with spaghetti ($8.25) and Shanghai noodle with pork, chicken or beef ($8.25). All include soup, a dumpling, a jiggly square of red Jell-O topped with a tiny dollop of whipped cream and coffee or tea.

The restaurant’s top three requested items are the above-mentioned roast pork platter, oxtail stew and beef tongue with gravy. It is doubtful that any baby boomer ABC could rank these enduring favorites.

FOOD, FOOD, FOOD

“Pay No Attention to the Cholesterol!”

Ken Sproul first visited Chinatown as a child with his mother in the 1950s. He recalls how she would look over things in the food markets, pick some of them to take home and experiment in order to create what she thought could be reasonably called “Chinese food.”

The Chinatown of my youth was Cantonese. As new immigrants have arrived from other parts of China and Asia, the food, the language and the non-tourist portions have evolved. In addition, parts of the Richmond and Sunset have become an extension of the city’s Asian community and in some ways are more “authentic” than portions of Chinatown.

The Chinatown of my youth offered strange and often delicious foods and smells, fascinating produce, live fish and fowl, maybe even turtles and frogs, all destined for some dish or another. Food stores had dried things of unknown origin: fish, fungi, roots, spices, and even reptiles. Drug stores had boxes and bins full of medicines and remedies that didn’t come with printed dosages. We experimented with dried fish and shrimp, but most of all, with dried mushrooms and fresh produce.

The meat and fish markets not only had cages of birds and tanks of fish from which you could directly purchase them dead or alive. They also had cuts of meat and parts of animals on display that were lessons in dissecting. I didn’t know that pigs had so many parts; both exterior and interior.

The vegetables on sidewalk stands ran the gamut from the familiar to the totally unknown. Melons, eggplants, citrus fruits, beans, and greens came in a bewildering array of styles and shapes with very little in the way of descriptions or identification. Sometimes we would just buy and experiment.

The best part of the food markets were the places with prepared foods. Ducks and squabs hanging in the windows, salt chicken and the king of the hill: whole roasted pig. It was always a glistening golden brown that you could buy by the piece or by the pound. A magician with a cleaver would turn it into bite-sized pieces to fit into a carry-out carton. A whole duck would be reduced to fit into a quart sized container filled with juices. Pay no attention to cholesterol! Take it home and eat, but if you put it in the refrigerator it may look a little less appealing in the morning.

Outdoor produce shop on Stockton Street. Produce arrives fresh early every morning, and the best of it is quickly sold. Photo by author.

There were also steam tables with rice, noodles, squid, chicken, fish, shrimp and duck. With everything smelling great all were a great temptation. Bakeries with a range from steamed pork buns to almond cookies were the last stop.91

GREAT FOOD FROM GREAT OLD PLACES

The Best from the 1960s

Former Chinatown resident JuJu Lee provided a list of her favorite dishes from the 1960s along with the restaurant of choice in which she or her family once ordered each. All of the food and all of the restaurants were much simpler and more basic in nature than their modern-day versions. Not a single one of the old-time Chinatown dining spots played music or had a television set for diners to watch as they ate. Conversation-based social interaction was the order of the day. Most of the listed restaurants are gone, although one of the best known, Sam Wo, recently reopened at a new location. JuJu calls her list “The Best from the 60s.” 92

• Tomato beef chow mein from the Chinese Kitchen.

• Beef casserole with raw egg from Jackson Café.

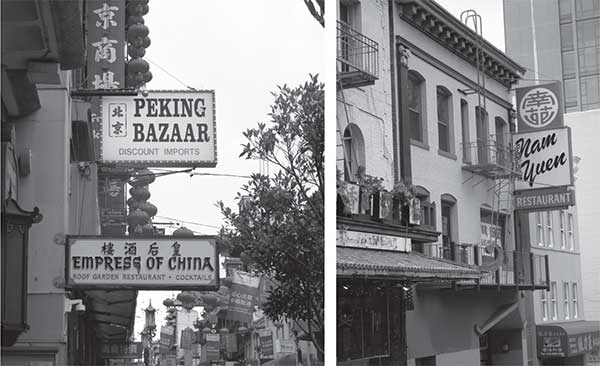

• Op gun yee fu wonton from Nam Yuen.

• Sam see fun (with abalone, chicken and cha siu) from Kum Hon.

• Beef gon won ton from Sai Yon.

• Gai bow from Yung Gee.

• Cold noodle roll with pork from Sam Wo.

• Custard pie from Sun Wah Kue.

Sun Wah Kue featured Chinese and American food and was located on Washington Street between Stockton and Grant, right by Ross Alley. Most Chinatown folks went there for the American fare that included three-course lunches or dinners centered on main dishes such as roast beef, pork chops or beef tongue. All were accompanied by Parker House–type rolls and pats of real butter on a tiny chilled platter. Breakfasts included bacon and eggs, omelets and waffles that came with individual portions of maple syrup in little spouted ceramic cylinders.

Sun Wah Kue’s cash register was right by the restaurant’s entrance. It was a large, manually operated beast of a machine that rang whenever opened; it sat behind a cage of gilded bars. There were family booths made of worn but polished wood panels to the left side of the restaurant. Every booth featured a patterned gray-hued marble top table large enough for about four adults and an equal number of kids. The main dining room was filled with circular tables for four that were also topped with gray marble. To the right of the dining room was the counter, topped in the same marble found throughout the restaurant, to which swivel stools were attached. The large stainless-steel coffee makers and glassed-in pastry shelves occupied the wall beyond the counter. Coffee was served in heavy beige-colored ceramic mugs for a dime a cup. The house special baked goods included the above-mentioned custard pie along with apple pie, orange chiffon pie (it was just called “orange pie”) and sugar donuts.93 As late as 1970, a pie to go cost ninety cents and the sugar donuts were a nickel each. Customers could elect to take two different types of half pies for the same ninety cents as for a whole one. There were also cakes, a memorable one of which was the Peanut Cake. It was a three-layered yellow type with white frosting generously sprinkled with crushed roasted peanuts.

Leland Wong, a longtime Sun Wah Kue patron, recalled stopping by just prior to its permanent closure: “One of the last times I walked in there it was pretty sad. Upstairs was leaking water into the restaurant and there were buckets to catch the water. The store was open as usual, but I don’t think the restaurant part was serving food anymore.”94

Jackson Café was on Jackson between Grant and Kearny. It had a long counter that extended along the left-hand side and bench-seated booths that went down the right-hand side. The cash register, a smaller, simpler and more modern device than the one at Sun Wah Kue, was behind a glass counter filled with candy and gum for sale. Except for its Chinatown ambience, the café easily resembled a typical American coffee shop of the 1950s and ’60s. Like Sun Wah Kue, Jackson Café served both Chinese and American food. Unlike Sun Wah Kue, however, most of the diners at Jackson Café preferred to order Chinese or the hybridized Chinese American rice platters that were a throwback to the exclusionist bachelor days. The beef casserole listed previously as one of “the best from the 60s” was one of the café’s popular rice plates. It cost about one dollar in the ’60s and came with all the oolong (black) tea that one could drink. Other such plates that featured the main ingredient heaped upon a generous portion of white rice included beef stir-fried in oyster sauce (or with greens), oxtail, roast pork and beef tongue. All were nicely drenched in sauce or gravy. In the evenings, there always seemed to be several single men at the counter quietly having their rice plates for dinner. Two American dishes that a Jackson client remembered as his all-time favorites were veal cutlets and fried chicken.

Pretty much any of the other “best from the 60s” Chinese dishes could be found at Jackson Café. In the mid-1960s, a two-dollar order of tomato beef chow mein, always made with fresh tomatoes as well as onions and green peppers, would easily satisfy four fairly hungry people. A curry-flavored variant of this chow mein was also very popular at Jackson and other restaurants throughout Chinatown. Another chow mein favorite from Jackson was the sang gai see chow mein that, as indicated by its name, was made with fresh shredded chicken.

Gai bow were a chicken-filled version of the more famous cha-siu bow, or roast pork bun. Both came in either a steamed or baked version. Steamed gai bow bore a red dot of food coloring on their tops to distinguish them from the lookalike pork buns. The ingredients for the bread were essentially the same as for any yeast roll: yeast, flour, a bit of sugar and possibly some shortening. Another bow variant was the lop cheung bow, filled with the sausage of its name. The sausage is a hard and dried pork-based product.

The sausage’s appearance is dark maroon-brown, variegated with grayish white globs of tasty fat, and it is shaped like a thin cigar. Appearance and questionable healthiness were never deterrents to the popularity of lop cheung. It has also been called fung-cheung (fung means “wind”). Back in the villages, the sausages would be hung in the open air to cure. Lop cheung bow, a little hard to come by in the present day, were easily distinguished from their roasted pork or chicken variants by their oblong shape.

Sam yee fun was three-flavored (or three-ingredient) stir-fried fun. Fun is a generally thick and wide rice noodle. One of its oldest and most popular versions is gnau-yuk chow fun—fun stir-fried with beef, soy sauce and onions. In the case of the listed “best from the 60s” version, the ingredients or flavors were stir-fried slices of abalone, chicken and cha siu.

One former Chinatown kid said: “I have always loved a good simple beef chow fun. I have tried to cook it at home but, even with the right ingredients which are pretty basic, it is hard to do right. I don’t have a wok and I think that is the key. I have read where it is supposed to be cooked over really high heat, in a well-seasoned wok, and with just the right amount of oil. All I have is an electric stove and flat nonstick pans, so if I really want decent chow fun, it’s off to a restaurant.”

Noodle rolls, also called cheung fun, can be served either hot or cold. The word cheung refers to “guts” or “intestines,” because the rolls look a bit like lengths of pig intestine. Popular in practically all dim sum places, it can be made with any variety of ingredients to include dried shrimp, ground beef, vegetables or roast pork. It can also be served plain. Cheung fun of practically any variety was a staple of Chinatown’s old Sam Wo restaurant.

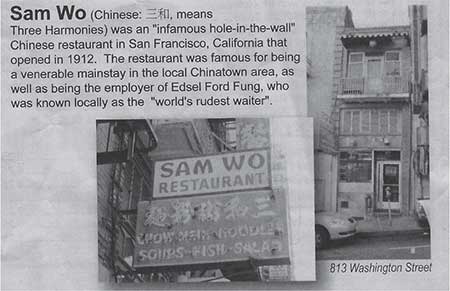

Sam Wo was a longtime Chinatown go-to place for families seeking comfort food, called siu yeh. The restaurant stayed open until 3:00 a.m. and always did a great takeout business. It was on Washington Street between Grant and Kearny and opened just after the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. It was only about ten or twelve feet wide and was three stories high. The kitchen was on the ground floor, and customers walked up stairs just to the right of the door to get to the dining areas. Since the restaurant was so narrow and crowded, food orders had to be sent up from the kitchen by a dumbwaiter. The dining rooms had marble-topped tables surrounded by stools. A former customer said:

Everything about Sam Wo was basic, but good and no-nonsense. They served chow mein, chow fun, wonton, jook [rice porridge]…all the things we loved to eat in Chinatown. It was always good, with quick service and very inexpensive. Back in the ’50s and ’60s, the waiter or waitress didn’t waste time talking or setting the table. They asked what you wanted, came back with it and a pot of oolong tea, put it all in front of you with a pair of chopsticks and, if your dish called for it, a soup spoon and left you alone. I hated it when sometime in the late ’60s or early ’70s, the place got discovered by lo-fahn (non-Chinese). They would come in crowds and line up down the street just to get in. Then it got written up in tourist books and things got really bad. The out-of-towners didn’t even know what to order. Before all that, I never had to wait to get in even if the place only could seat about thirty or forty people. I went one time in the ’70s when I saw that there was no crowd and ordered my old standby: tomato beef chow mein. It was awful! They were using canned tomatoes.

Former Sam Wo customer Marilyn King bemoaned the loss of her onetime favorite stir-fried noodle dish, gon lo mein: “Sam Wo’s gon lo mein had a distinct flavor. I think it came from being cooked with a combination of sesame oil and oyster sauce. I don’t know where we can get anything even close to that any more. I met a cook once who cooked it and eventually became a part owner of Jackson Café. When he made beef gon lo-mein for me at his own restaurant in San Mateo I thought I was in heaven. Unfortunately, he passed on within a year. His son tried to duplicate the dish, but it was not the old school way and taste.”95

JuJu Lee, a well-experienced aficionado of Chinatown lo mein, said: “It’s hard to believe that not many can replicate the old school style of Cantonese cooking. Simple flavors. Good fresh ingredients. Good oil and not smothered in garlic or hot sauce.”96

Sam Wo remained in operation until 2013. It was shut down for health and safety reasons that the owners found too expensive to address. Back in the heyday of the baby boomers’ Chinatown, the deficiencies identified at Sam Wo, health and safety notwithstanding, were not uncommon in practically all of the neighborhood’s eateries. Sam Wo was reestablished in a new location on Clay Street between Grant and Kearny in 2015. It has attempted to keep many of its old favorites on the menu.

In Chinatown, fresh seafood was never a problem, either in restaurants or at a market. Some markets on or near Grant Avenue featured outer walls that were actually the fronts of fish tanks. Live fish swam behind the thick glass; all a shopper needed was to identify a specific fish before it was scooped out with a net, popped on the head with a wooden bat and sold. Live crab or snails were often placed in pans or buckets on the sidewalk in front of a store. Fish that had already been killed, some of them cleaned or even fileted, could be found neatly stacked on crushed ice inside the store.

Pictures and history of Sam Wo from the back of its 2015 takeout menu. Photo by author.

One former Chinatown kid recalled a family recipe made from fresh-caught fish. The resultant dish is a traditional one that is supposed to be eaten on the seventh day of the Lunar New Year celebration. The women of the family—mother, aunts and grandmother—would make a raw fish salad with pickled ginger, scallions, fried rice noodles, cilantro, sometimes preserved black eggs and lettuce. The dish would be topped off with lemon juice squeezed all over it.

Preserved black eggs have been called “100-year old eggs.” The weathered and aged appearance that they take on is due to the preservation process. They look very much as if they had been around for as much as a century. In reality, the aging of the eggs can last as little as several weeks. The eggs are packed in clay mixed with other ingredients that allow for biochemical processes to occur that ultimately produce a black-colored product of strong and pungent flavors. These eggs can be from chickens, ducks or quail and can be eaten alone or used for flavoring.

CHINATOWN TAKEOUT

Like a Proto–Panda Express, but Better

A general characterization of the typical Chinatown family of the postwar period would likely include the descriptions “always busy” and “having little money to spare.” Moms and dads often worked long hours for low earnings, and the kids could usually be found helping out in a family business after school. If not working or attending Chinese school, older kids were frequently charged with caring for younger siblings and helping with household chores that sometimes included making dinner. The presence of shops and restaurants that made and offered good food to go at reasonable prices went a long way to offer some downtime for families around the dinner hour.

Several markets such as the Ping Yuen Supermarket (not associated with the nearby and similarly named housing projects) sat about midblock on Grant between Broadway and Pacific. It offered pre-cooked dishes from what could be called its “deli section,” set behind a well-heated glass counter. Shoppers could order full-course dinners of complete dishes of vegetables, meat, seafood or fowl. Cooked white rice and desserts were also available. While Chinese families did not traditionally serve dessert, the American custom could not be ignored. One of Ping Yuen Supermarket’s signature dessert dishes was a peach tart that had a pie-like crust upon which a canned peach half was placed. A swirl of whipped cream completed the delicacy, which came in an appropriately miniaturized foil pie pan. Ping Yuen may have also been the first place in Chinatown to offer baked cha siu bow. While the steamed versions found throughout Chinatown cost about a dime, the much larger Ping Yuen baked bow were sold for a quarter. Despite the greater cost, they tended to sell well as much for the novelty as for their larger size and generous and perfectly moist filling. Instead of just plain cha siu, the Ping Yuen bow included bits of onion, celery and other little things.

There were also small kitchens with a storefront that operated solely as takeout places. One such was the well-liked and versatile Chinese Kitchen. Several of its former customers remembered that it was on the corner of Mason and Pacific and that the Powell–Mason cable car line ran right past it. It was for takeout or delivery only, and some believe that it was opened by Johnny Kan (owner-operator of Johnny Kan’s in Chinatown and Ming’s in Palo Alto). One of its old customers thought that it was the first Chinese takeout place in the country and that they made your food to order. This former patron added that it was the prototype for the drive-up, takeout, fast-food chain currently seen everywhere: Panda Express. Chinese Kitchen’s most consistently cited favorites were (in no order) tomato beef chow mein, won ton and gon-lo-mein.

There were also the clandestine takeout spots. Many restaurants had side doors that opened up to alleys. Most of these doors went directly to the kitchen, and they were usually at least partially opened to help keep down the heat from the stoves. People in search of prepared food would go to these spots, catch the attention of a worker and place an order. In some cases, this would be a legitimate transaction, but in others, it was a means of extra income for the kitchen staff. “I really liked the ‘covert’ or ‘contraband’ Won Ton from Sun Hung Heung restaurant. The kitchen helpers sold it out the side door on Wentworth Place. They gave it to you in recycled cans, but if you brought your own pot, it was always a little cheaper.”97

Another takeout regular recalled: “My mom used to bring her own pot with lid to Sun Tai Sam Yuen restaurant for soup. It sustained our family of four for a week!”98

Yet another bargain-seeking diner-in-a-hurry recalled that practically everybody in his family would go to Sam Wo for either jook or won ton and that they always brought their own containers. He spoke fondly about taking the train to Santa Cruz for the day once or twice each summer with his parents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Leaving from the station at Third and Townsend Streets, the train was called “The Suntan Express,” and it stopped right at the beach and boardwalk. The family’s picnic lunch was always jook bought ahead of time from Sam Wo. One of his mother’s saddest moments was the time she forgot to take her jook container from the train after it returned them to San Francisco. She went on and on about how her container was the perfect pot for jook and how anything else she used after it was lost just wasn’t the same. She went so far as to say that even the jook tasted different after that.

KUO WAH: ONE OF THE OLDIES

The Premier Restaurant in Chinatown

Very few of those born and raised in Chinatown have forgotten the old Kuo Wah restaurant. It had been established during the prewar era, so by the time the boomers came along, it was already a thriving place that was popular with the neighborhood’s families. It was open from 10:30 a.m. until 3:30 a.m. An old menu from either the 1940s or ’50s shows that a full dinner for one ranged in price from just $1.00 to $2.50. The items ranged from reasonably traditional Chinese dishes (chow yuk, bird’s nest soup and wonton) to those concocted largely for the tourist trade (sweet and sour pork and egg foo young, for example). Won ton was helpfully described on the menu as “Chinese ravioli.” The dollar meal would include soup, chow mein, fried prawns and rice. The banquet table–sized dinner for seven cost $22.00 and included bird’s nest soup, chicken wrapped in paper, chicken with cashew nuts, “Yangchow” fried rice, mushroom chicken chow mein, egg rolls, fried prawns and sweet and sour pork. Additional diners beyond seven would be charged an extra $0.25 per person.

Andy Young, the grandson of the original Kuo Wah owners, recently contributed his memories about the restaurant:

My grandfather Chin Mon Wah and his childhood friend Chin Kwok Yuen purchased the building in the late 30s. They remodeled it to house the Kuo Wah café at 942 Grant Avenue which served American style food. The part of the restaurant that was 946–950 Grant Avenue served Chinese food. The Lion’s Den nightclub was in the basement and its entrance was at 942. This is where the bar was located at the time. The Lion’s Den had shows featuring Chinese performers who would sing, dance, and tell jokes just like at the mainstream nightclubs of the era. The Gum Mon Hotel still remained in the building’s upper two floors.

Sometime after World War II, I’m guessing the late/mid 50s the Lion’s Den ceased to exist due to the changing times and became a dining room. Its bar was relocated to the main dining room which served American food. Many politicians, heads of state and dignitaries were hosted. We have the names of the signatories to the United Nations Charter written in Chinese characters from when my father hosted them when they met in San Francisco in 1945. The Kuo Wah, I’m told, was the premiere restaurant in Chinatown and was known world-wide.

In the early 60s my father undertook major construction. The Lion’s Den basement, main floor Kuo Wah café, and second floor hotel rooms were remodeled into a single restaurant called the Kuo Wah restaurant instead of “café.” The second floor hotel rooms were cleared to make way for a 300+ person dining room. An outdoor courtyard was created at the front entrance of the building so that diners could sit out on nice days to eat or have cocktails. Between ’65 and ’68 there was a nightclub in the basement called the Dragon-a-go-go which featured local bands. The group that I remember the most is The Whispers. They still tour. We also hosted lunch once a month for a “Theater in the Round” where Hollywood stars that were in town met the press. I have pictures of Bette Davis, Rip Torn, Elaine May, Mike Nichols, Buster Keaton and others. The general theme of the place was that of an old rustic Chinese village. We sold the restaurant in 1975 to investors. They rebuilt it once again to make a Hong Kong style dim sum eatery.99

MISTER JIU’S: SOMETHING NEW

A Symbol of Hope and the Next Generation of This Neighborhood

Unless they have immediate family, usually an aging parent, still living in the neighborhood, many of those who grew up in Chinatown do not visit it much anymore. They cite the congestion and lack of parking as primary reasons why they stay away. Distance and the heavy Bay Area traffic deter those who have moved down the peninsula or to the East Bay. Those who remained in San Francisco also say that Chinese restaurants and groceries are just as plentiful in the Richmond and the Sunset. Several blocks of the Richmond’s Clement Street have become what might be called a “satellite Chinatown.” Even in neighborhoods where there is no significant number of Chinese or Chinese American residents, there are often shops, groceries and restaurants that can satisfy their needs.

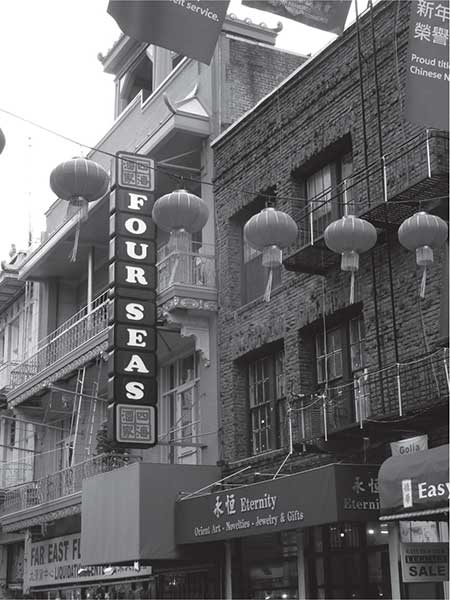

Restaurateur Brandon Jew has been uncomfortable with the changes that he sees in San Francisco’s Chinatown. He misses the presence of a closely knit and family-oriented neighborhood. He is particularly concerned that demographic and economic changes may bring about a downfall to Chinatown such as has already devastated similar communities across the country and even in Canada. Jew fears that once-thriving Chinese and Asian American communities in Los Angeles, Seattle, Vancouver, Chicago, New York, Boston, Philadelphia and elsewhere have become “ghost towns.” In response to these concerns, he recently opened a new restaurant, Mister Jiu’s, at the site of one of Chinatown’s longtime stalwarts: the Four Seas. Brandon spoke about his enterprise: “To me this restaurant is hopefully going to be a symbol of hope and the next generation of this neighborhood. I think for a long time, a lot of other Chinatowns like L.A. or even Vancouver, they’re becoming like ghost towns. The Chinese community doesn’t really live there anymore. There’s something I thought was special about this neighborhood. It’s continued to be a place for immigrants to reside in. The restaurant is a place to celebrate the history and the vibrancy of this neighborhood.”100

Brandon’s family background is familiar to that of many boomer ABCs. His father was born in Toishan, and his mother’s family was from Long Du, to the north of Toishan. His parents came to the United States in the 1920s to join one of Brandon’s grandfathers who, he assumes, used fake papers for entry. Brandon recalls trips to the Chinatown markets with his mother when he was a child. He maintains vivid images of the crowds of shoppers standing shoulder to shoulder as they pushed and pressed against one another in competition for what each deemed the “best” ingredients for that evening’s dinner. He states that a large part of his inspiration as a chef comes from the way things were in his childhood—the way Chinatown was in its postwar glory days. He strives to carry out and express the traditions of his parents through what he hopes to do at his restaurant.

The Four Seas Restaurant was a favorite Chinatown family banquet venue for half a century. Photo by author.

Number 28 Waverly Street. Formerly the back of the old Four Seas, it is now the front of the new Mister Jiu’s. Photo by author.

Two longtime favorite family restaurants. New places throughout the Bay Area have opened, so many old-time ABCs no longer visit Chinatown. Photos by author.

We’re looking at doing red egg parties. To have a space that we can host parents to have a red egg party for their kid, those are the kinds of celebrations I want to continue for our culture. If we are able to do a wedding here, that would be cool, too. In general, I think we’re looking to just have a place that people can celebrate in. And we hope that people will come here to celebrate the food and the neighborhood, and the history of this neighborhood, and the future of this neighborhood, too.101

AMERICANIZATION THROUGH DESSERT

Blum’s Koffee Krunch Kake Is to Die For

For Chinatown baby boomers, dessert was not a part of most meals. Dessert was simply not a “Chinese thing,” the squares of red Jell-O from places like Sun Wah Kue or New Lun Ting notwithstanding. To be sure, there were numerous bakeries that produced goods such as pies and cakes, but these were often what afternoon callers would bring to the homes of their hosts. The bakery items would then be served with coffee during general conversation. A major exception was when there was a birthday celebration. In such cases, a cake from places like Eastern Bakery, Sun Wah Kue, Ping Yuen (supermarket) or elsewhere in Chinatown would be served, complete with candles and ice cream.

One bakery outside of Chinatown that was known to many of its residents, both young and old, was Blum’s. There were several of them, but the nearest and most convenient was at Union Square. It was a small shop in which clients could sit with coffee over baked goods. Most just popped in to get something to go. The last of the Blum’s closed in the 1970s. Its trademark cake, the one most revered by those living in Chinatown, was its Koffee Krunch Kake. It was a simple concoction. An airy sponge cake was baked with the flavors of vanilla and lemon. Heavy whipped cream was then applied between its layers as well as on top and all around the sides. It was then covered with crushed pieces of Blum’s signature coffee crunch candy.

Cooper Chow recently wrote:

You can still get the old Blum’s Koffee Krunch Kake at Japantown. Walk into the Super Mira Market at the corner of Sutter and Buchanan Streets and turn right. Single slices sell out by noon or earlier, but a whole cake to go is available all day. They are made daily by Tom Yasukochi, an 80 year old pastry chef. I have heard that Mr. Yasukochi learned how to make the cake 40 years ago from a former partner who was a former Blum’s candymaker.

My mom used to get a whole Koffee Krunch Kake from Blum’s for super special occasions like when relatives came to town from Phoenix. Otherwise she would regularly get strawberry shortxcake, apple pie, or custard pie from the old Ping Yuen Supermarket near the corner of Grant and Pacific. Eastern Bakery still makes a Coffee Crunch Cake, but I can’t compare because I’ve never had it. It was always Blum’s Koffee Krunch Kake for us back in the days. It was to die for.102

Eastern Bakery’s coffee crunch cake. Some Chinatown kids claimed it was better than the original Koffee Krunch Kake from Blum’s. Photo by author.

The old Eastern Bakery sign. Faded, chipped and rusty, it was recently replaced by a new look-alike. Photo by author.

Annie Leong Lum stated: “I have good memories of those cakes. I used to buy the coffee crunch from Blum’s until they closed. I tried Eastern Bakery’s version but it wasn’t as good. Chinatown’s coffee crunch cake has always been too light, airy, and not sweet enough. I also tried Japantown’s once many years ago and if I remember correctly it was very good. Yum! I think I need to make a trip there to satisfy my craving.”103

EGG ROLLS, EGG FOO YOUNG AND MORE

We Asked If It Was Really Chinese

In talking about his new restaurant, Chef Brandon Jew commented that there were some classic old Chinatown dishes that he hoped to perhaps reinvent. He stated that, in the case of many dishes, there was never a true recipe to begin with. One dish he mentioned was egg foo young. “Most of those who grew up in Chinatown were well aware of things like egg foo young, sweet and sour pork, egg rolls, chop suey, and the host of other things that they never ate at home. Those were, for the most part, tourist foods, or not real Chinese food. That did not keep some from trying them and even enjoying them.”104

P.J. Leong, a former educator from San Francisco’s Chinatown, was very clear about her favorite but probably never-served-in-China Chinese food. “Sweet and Sour Pork! That fried pork with sauce! It was such a treat to go to a red egg and ginger party buffet because they served ‘gwai lo’ [white man] foods there. We didn’t get sweet and sour at home. I still like it, but now I get the sweet and sour chicken! And a friend told me that her favorite is also sweet and sour pork made perfectly. She complained that most that are cooked nowadays are always soggy and coated with sauce. If anyone knows a place that has good sweet and sour; let us know!”105

A cousin of Darryl Eng’s recalled a home-cooked meal that his father once made:

My dad was born in China. He was a fun-loving person who enjoyed doing fun and nice little things for us kids. One day he said that he was going to make us something special for dinner: egg-foo-young. We asked if it was really Chinese, and he said something like, “Of course it is! I’m making it and I’m Chinese and you’re going to eat it and you’re Chinese, right?”

We watched him beat up a bunch of eggs, slice bean sprouts, green onions and cha-siu. He then pan fried it all until he had a stack of them on a plate. He then put them in the oven and told us to go play. He would call us when they were ready. A short while later we were at the table, each of the three of us and my parents with an egg-foo-young on our plates. I think we had forks instead of chopsticks. They looked fine, but I wasn’t totally comfortable for some reason as I took my first bites. It took me a few moments, but I figured it out. “Can I have some catsup?” My dad brought it to me and laughed, “Ah; you’re just too American!”106