The Angel Island Immigration Center did not welcome the Chinese so much as attempt to bar them from entry. Photo by author.

7

FRANCES AND CHERYL

DISCOVERING CHINATOWN THROUGH MARRIAGE

Two non-Asian women who met and would become sisters-in-law offer their views about San Francisco’s Chinese American community. The two women, one of whom subsequently divorced her spouse, married brothers who were born in Chinatown. They describe their experiences with their Chinese American family as well as with their discoveries in Chinatown. Since the couples moved away from California after marriage, the two wives were only rarely together at the same time at the home of their Chinese in-laws.

FRANCES MATHEWSON-LEONG, CHINESE BY MARRIAGE

“It Was Sometimes Uncomfortable to Be with the Leongs. And to Think, I One Day Became One”

Frances Mathewson lived in an apartment with a roommate in San Bruno after moving to the Bay Area from Riverside in the early 1970s to enroll as a graduate student at San Francisco State College.107 She first met her husband-to-be, Glenn Leong, in one of her classes. The two of them happened to sit next to each other. Frances had not known anyone who was Chinese before she started her coursework at State. Her only previous experiences with a Chinese American or ABC had, coincidentally, been with another classmate whom she had earlier sat beside in another class, Dennis Woo. Frances and Dennis became friends and went on several dates. Although they had enjoyed each other’s company, a relationship did not develop, and they eventually went their separate ways.

Frances remembers that she had been attracted to Dennis because he was a nice guy rather than because he was Asian. Her experiences with Dennis left her comfortable to explore a friendship with her new Asian classmate Glenn. While both of her Chinese American friends struck her as thoroughly Americanized, she could not help but wonder if they might show significant cultural or behavioral traits that were specifically Asian. She simply did not know what to expect. Neither Dennis nor Glenn seemed to be much different from any of the Caucasian boys she had dated or had as boyfriends earlier.

Gradually, Frances found herself attracted to Glenn and enjoyed his company enough to begin thinking of him as a boyfriend. That progress in the relationship soon led to the inevitable meeting of his parents. Glenn had briefed Frances with the information that his mother was an ABC who was a bit old-fashioned and that his father, born in China, had come to San Francisco through the Angel Island Immigration Station when he was eighteen. He reassured Frances that they both spoke English, although his father did so with a fairly heavy accent. Glenn also told Frances he had a brother and a sister living at home. Glenn was almost ten years older than his brother. The two younger Leongs were a year apart in age and still in high school.

Glenn took Frances first to meet his father at his workplace: the National Dollar Store on Fillmore Street. Mr. Leong was the store manager. It was close to noon, so the three of them went to lunch. They all walked across the street to a small restaurant in Japan Town.

Glenn’s father was nice. He shook my hand and smiled as he did so. I do not remember what we talked about…it probably wasn’t anything important, but I was relieved that Mr. Leong appeared cheerful and sincere about everything we had to say. He had a pretty heavy accent, and sometimes I couldn’t understand what he was saying. In the end, it didn’t matter. I was just happy that he seemed to be sincerely interested in me. I also had never had Japanese food before, but with both Glenn and his father explaining it to me and helping me to order, everything turned out fine. Until he got transferred to the Dollar Store in Richmond, Glenn and I would often stop by the Fillmore store to meet his father for lunch at Japan Town. Those were always pleasant times for me, and I would learn so much about the Chinese in America during my increasingly detailed conversations with Mr. Leong.

AN ANGEL ISLAND IMMIGRATION STATION ADMISSIONS INTERVIEW

“His Face Was Flushed, So He Must Have Been Lying”

Frances learned a lot about Glenn’s father through the chats that she shared with him during their Japan Town lunches. Even Glenn admitted that he had not heard some of his father’s stories before. Frances was fascinated by what Mr. Leong had to tell her about his earliest days in the United States.

I always knew about immigrants coming to America through Ellis Island in New York Harbor, but until I met the Leongs I had never heard of things like paper sons or Angel Island. Glenn told me that his dad had entered through Angel Island, but he never explained or offered any details. I don’t think he really knew that much about it. I didn’t know that Chinese were not allowed into the United States except under very strict provisions until 1943, and I was really surprised at how harsh the conditions were for Asian immigrants, who had to be cleared through on that island in San Francisco Bay.

I was amazed at how a lot of Chinese managed to get in by using false papers. That’s how I found out what “paper son” means. It’s basically where someone already in the U.S. legally takes money from someone in China to claim him as a “son” for immigration purposes. The immigration officials tried to catch people sneaking in by interviewing everybody about their supposed family backgrounds. I was glad that Mr. Leong was not a paper son, but I felt really bad for what he had to go through.

During his interview, Glenn’s father told me that he was asked about the arrangement of houses in his home village, the location of the village well and the distance to the nearest market. He told me that when asked about the color of the main door on a particular house, he answered, “red,” but was immediately told that he was wrong and that it was actually green. As far as he knew, that was the only question that he missed. After the interview, which lasted over an hour, Glenn’s father was told that his face was flushed so he must have been lying. He was only seventeen years old at the time, and he said that he was really nervous but was telling the truth. The immigration personnel did not believe him, and he was not initially granted entry. Eventually, the well-to-do San Francisco family that Glenn’s grandfather worked for as a cook and houseboy vouched for Mr. Leong, and he was allowed in to San Francisco and the United States. This was in about 1934.

The Angel Island Immigration Center did not welcome the Chinese so much as attempt to bar them from entry. Photo by author.

Bunks in the male detention barracks at the Angel Island Immigration Center. Photo by author.

A former Angel Island immigration inspector recalled the general nature of an interview:

We started by getting the data on the applicant himself: his name, age, any other names, and physical description. Then we would ask him to describe his family: his father—his boyhood name, marriage name, and any other names he might have had, his age, and so forth. Then we would go down the line: how many brothers and sisters described in detail— names, age, sex, and so forth. Then we would have to get into the older generations: parental grandparents; then how many uncles and aunts and they had to be described. Then the village: the district, how many houses it was composed of, how arranged, how many houses in each row, which way the village faced, what was the head and tail of the village. Then the next door neighbors. Then describe the house: how many rooms and describe them. What markets they went to…we had to get the main details of [the home] and how the family slept, what bedroom each occupied. Sometimes it would take three or four hours to examine each one.

Major discrepancies would be cause for deportation. For example, if an applicant said his village consisted of ten houses and five rows, two houses in each row and the alleged father said 30 houses and ten rows…or if the applicant said his father had three brothers and the father only had one brother. It was a question of testing them on family history. I don’t see how we could have handled it in any other way in the absence of [more or better] documentary evidence. When a person came in from a little village, who would know them? There was just one way of finding out if the family belonged together as it was claimed and that was by testing their knowledge of their relationship.108

Frances met Glenn’s mother one weekend at the Leongs’ house, which was on Tenth Avenue in the Richmond. She mainly remembers that she was pretty nervous about it. Things went reasonably well, and Frances admits that her own nervousness made her feel more uncomfortable than she probably needed to. Glenn and Frances eventually moved in together. They rented an apartment near Ocean Beach in the Sunset. Frances does not think that either of Glenn’s parents had any difficulty with it.

It seemed odd to me that Glenn’s mother never addressed me by my name for about two years. Glenn said something about how Chinese families were rarely openly affectionate and that family members usually addressed one another by title or by whatever each person’s standing in the family was rather than by name. He even told me that his father called him “Boy” a lot while he was growing up and that he sometimes slipped and still did that. His mother was American born and had to be American enough to be comfortable calling me by name. On the other hand, I only ever addressed Glenn’s parents as Mr. or Mrs. Leong.

Although I spent more time with his father than with his mother during the early part of my relationship with Glenn, Mr. Leong was still pretty reserved in a lot of ways. Between my own observations and what Glenn would tell me, I understood that conservative behavior was just a Chinese cultural thing. It wasn’t customary for them… the Leongs or any other Chinese…to be expressive, or personal or emotional. This was the opposite of my own family, so it was sometimes uncomfortable to be with the Leongs. And to think, I one day became one! The Leongs always asked about my parents, though, and I always felt good about that.

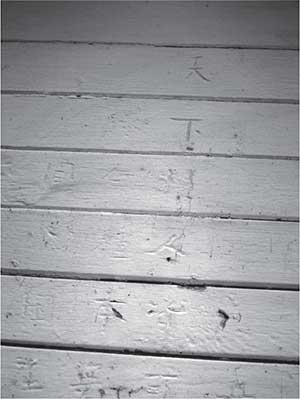

Hand-carved poems decrying the harsh conditions endured by hopeful immigrants being held on Angel Island. Photo by author.

VISITING CHINATOWN

“I Loved It”

As Frances and Glenn grew closer together, she took increasing pleasure in seeing and experiencing Chinese culture as it was to be found in San Francisco and as Glenn and his family practiced it. Frances had determined early on that Glenn was, at best, only nominally interested in being Chinese. She simply saw him as another American, and that was how she knew that he preferred it. She was happy, however, that he would take her to Chinatown and show her the “native” side of it.

Whenever we went to Chinatown or the Chinese part of Clement Street, I loved it. It was a new world that was being opened up to me. I reveled in the fact that I was not just another tourist spending a part of a vacation afternoon going through Chinatown’s streets and shops. I really enjoyed the little stores, places to eat and movie theaters. And the food stalls on Stockton Street made me feel as if I were in a market somewhere in China. There were a lot of familiar things, of course, but there were so many things that I had never seen or even imagined before. As time went by, it was fun to look at some of the Stockton Street produce, meats, prepared foods and snacks and know that I had eaten some of them and liked them! Often I would be the only non-Chinese person in some of the places we went to. I didn’t feel odd or out of place. I just enjoyed it so much. I remember going to the movies, and people, especially the young kids, would just look at me. I felt like a Chinatown insider. This was especially true when Glenn would point out places he went to or where he played when he was younger, or where his friends used to live. I just thought it was all very cool.

One of the first times I ever had dim sum was in the Hang Ah Tea House. It was in a narrow alley and it was a dive, but in the good sense, like when a place is really something unique and you get a special feeling just being there. Glenn ordered, of course, and I don’t think there was anything that I didn’t like. One time, shortly after that, I tried my hand at making some dim sum, since I had really begun to enjoy eating it. I even made my own cha-siu from scratch for the steamed cha-siu bow [pork buns]. I made bok-tong-go [sugary rice gelatin], because Glenn told me he had always liked it, siu-mai [meat dumplings] and a few other things. I wasn’t trying to prove that I could be Chinese or something. I have always enjoyed cooking, and I thought it would be fun and challenging to try to make something that was so exotic to me. Glenn told me that he thought it all turned out pretty well, and he expressed admiration for what I had done. I was pretty pleased, of course. Dim sum is very involved and even complicated to make. It was also totally foreign to anything I had ever tried before in a kitchen.

Well, when I took some to the Leongs, I was disappointed that Mrs. Leong seemed a little critical. I’ll admit that she was trying to be kind, but I was bothered nonetheless. Glenn explained that all Chinese take their dim sum very seriously and they do not tolerate even the slightest imperfection. He said that his mother just “slipped” into her “Chinese mode” out of habit. I think he was just trying to cover for her.

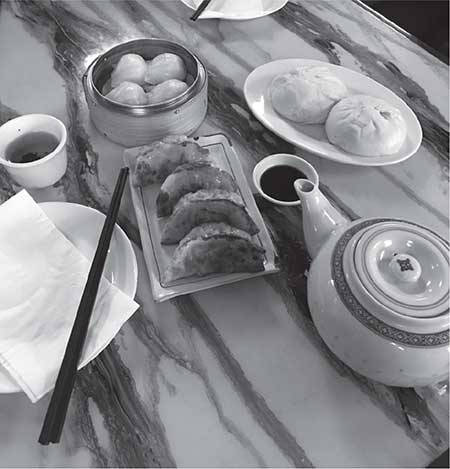

Dim sum. Payment used to be calculated by the number of steamer baskets. Some clients would hide or toss them out windows. Photo by author.

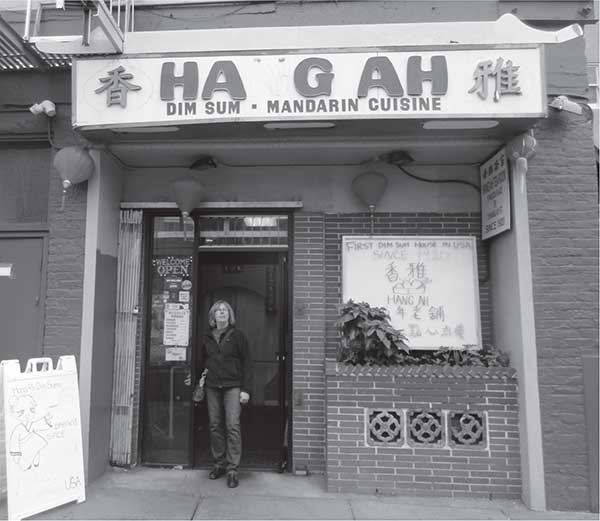

Hang Ah restaurant is the oldest continually operating dim sum establishment in San Francisco. Established in 1920. Photo by author.

Then there were the Chinese movies. I was initially worried that I wouldn’t like or understand them, but it wasn’t long before I became a big Shaw Brothers fan. It really helped that there were subtitles in English as well as in Chinese. We usually went to sword-fighting and martial-arts films. The costumes and settings were historical, and I guess that I would roughly compare that kind of film to the American Western. My favorite actor of the 1970s was David Chiang. And my all-time favorite movies are Heroes Two and Five Shaolin Masters. I became a big Bruce Lee fan, also; but David Chiang and the two Shaw Brothers films I mentioned are the tops for me. I liked Alexander Fu Sheng, too. It took a while for me to find them, but once I did, I made it a point to buy the Shaw DVDs, and I still have them. I went to the Great Star Theater on Jackson Street most, but I also remember the Sun Sing Theater. Glenn never took me to a musical or any of what he called the “girly movies.” I guess I don’t miss what I don’t know. I couldn’t get into those salty preserved plum snacks or the melon seeds that Chinese people munch on at the movies, though. But going for siu yeh [snacks or good-old Chinese comfort food] afterward was the best!

I enjoyed the orange pie at Uncle’s on the corner of Waverly and remember that a slice of pie and coffee came to a quarter in the early ’70s…a dime for the coffee and fifteen cents for the pie. Glenn always liked Sun Wah Kue for its apple pie, but for some reason, I never cared for the place. I also remember eating tomato beef chow mein, or its variant with curry at the Jackson Café. Chow fun was another favorite of mine. A couple of times, we would just pop into one of the places that had ducks and siu-yuk and cha-siu hanging in the window to buy a half pound of something to snack on while walking down Grant or Stockton. A couple of times, Glenn would coach me on how to say things, and I would go in by myself to get our snack. I thought it rude one time when a counter woman laughed at what I said. I knew that she understood me. I wouldn’t have laughed at her English.

OLD CHINESE LADIES IN LARGE GROUPS

Raw Terror

After about four years of dating and living together, Frances and Glenn got married. Settling into married life and forging closer ties to her in-laws, Frances remembers how Glenn’s mother would spare her no detail about her battles with the older immigrant women who had come to San Francisco in the late 1960s or early 1970s.

Since Glenn’s mother had never learned to drive, she depended on the San Francisco Municipal Bus System. She would often take the bus from work to Chinatown in order to do her food shopping on Stockton Street. Whenever she was at the produce stalls, she always said that she felt besieged by her fellow shoppers. She called them “pushy” because, according to her, whenever she was at one of those sidewalk produce shops, “loudly gabbing, shabbily dressed and rude old hags” would push her aside and snatch whatever fruit or vegetable she was looking at “practically right out of my hands.” She repeatedly stated that they acted like “a bunch of ignorant peasants who thought they were back in their old villages.”

After her shopping or other Chinatown errands, Mrs. Leong would have to get back on the bus to get home. She seemed to enjoy complaining about it so much that I thought it was a little funny. She would say things like, “Those damn peasants are so uncivilized! They don’t wait their turn to get on the bus. They just push and shove. They don’t care if they step on you or knock you down!”

Even though she spoke Chinese a lot and acted Chinese in certain ways, Mrs. Leong was thoroughly American. She sometimes complained about how frustrating it was for her to understand some of her coworkers in her office building who were recent immigrants from Hong Kong. They would only speak Cantonese to one another, which Mrs. Leong couldn’t understand. She would go on to me about how they were so unwilling to act more American. I thought it was pretty funny.

Since neither Glenn nor Frances had a car, they also relied on the bus. Looking back, Frances remembers it all too well. Thoughts of the number 30 Stockton bus, ever so slow and ever so crowded as it lurched its way through Chinatown, still evoke the raw terror that only hordes of hissing, cackling and scrabbling Chinese harpies could produce as they elbowed, stomped and shoved their way past any and all unfortunate or foolish enough to stand before them. It seemed to a bewildered and overwhelmed Frances that these women—dumpy and diminutive, dusty and disheveled—were in a constant struggle for survival. To her, they all bore the hardscrabble look of people who had always been forced to fight for every little thing they could get just to get by.

MORE PAPER AND ANGEL ISLAND AGAIN

Mrs. Leong’s Father Paid a Matchmaker in China

Unlike her husband, Glenn’s mother did not have much to say about her childhood or adolescence. Whenever Frances asked her about it, she would get noncommittal responses such as, “Oh, you know. I just went to school, played with my friends and then got a job and got married. There’s nothing special to tell.” Frances’s curiosity had been piqued by her father-in-law’s stories, and she could not help but wonder if there might not be something as interesting about Mrs. Leong and her side of the family. Since she was always comfortable talking with Glenn’s aunts, uncles and cousins, she managed to slowly learn quite a bit about her mother-in-law and her family.

Mrs. Leong’s father was a paper son who first entered the United States in 1903 while he was still a teenager. One of Glenn’s cousins who is very into the family history sent me a copy of an immigration department document about their maternal grandfather. Part of it reads as follows:

“Wong Hung Fong [is] the minor son of Wong Si Fong and that said Wong Si Fong [is] a merchant lawfully domiciled and resident in the City and County of San Francisco, State of California, and engaged in business therein as a member of the firm of Nom Sang Lung, & Co., which said firm is engaged in buying and selling and dealing in merchandise at a fixed place of business, towit—at No, 900 Stockton Street, in the said City and County of San Francisco.”

The man who would become the father of Glenn’s mother as well as several aunts and uncles was a paper son who listed his paper father’s home village of Nam Lok as his own. His actual village was Fong Han. Rather than Wong, his real surname was, in fact, Lew. Unlike his father, Glenn’s mother did not elaborate on how her father’s Angel Island interrogation went. It is apparent, of course, that he learned about Nam Lok village well enough to quickly gain entry.

His mother did, however, tell Glenn stories about her childhood to entertain him when he was very young. He passed some of them on to Frances as best he could. She recalled one of them:

Mrs. Leong’s father had eight children who survived by his first wife. Mrs. Leong was the second-youngest one. When she was just three, her mother had become severely ill with tuberculosis and asked to be allowed to return to China so she could be buried on native soil. Her eldest brother, who was fourteen at the time, and one of her sisters, who was eight, accompanied their mother on the trip. Glenn’s grandmother died just one day out of Hong Kong, however, and his future aunt and uncle stayed in China for a year before returning to San Francisco in 1930.

When Glenn’s uncle and aunt arrived back in San Francisco, his grandfather decided that he had too many children and too little money with which to care for them. The two youngest ones, Glenn’s mother to be and her younger sister, were sent to an orphanage.

Glenn’s mother and aunt were sent to what is today called the Gum Moon Women’s Residence and Asian Women’s Resource Center at 940 Washington Street in Chinatown. When Glenn’s mother and aunt went there in 1930, Gum Moon (meaning “Golden Door” in Toishan Chinese and founded in 1868) was still known by an earlier name, “The Oriental Home.” It was a full-time orphanage that kept girls until the age of eighteen. The girls would attend school outside of Gum Moon but earn their room and board by working around the residence. The older girls also helped with the younger ones. Over the years, Gum Moon’s mission has evolved with changing times and community needs, but its general philosophy of providing aid, education and spiritual guidance to women and children with neither a family nor means of self-support has remained constant.

Frances continued:

Mrs. Leong, even though she was older than the sister she was with, could not adjust to being at Gum Moon. She cried all the time, and the staff members were at wit’s end. Eventually, the family’s oldest daughter, only in her early teens, made a commitment to her father, Glenn’s grandfather, to personally take care of her distraught little sister. This aunt was already tending to her other five siblings, so she thought that one more wouldn’t make that much of a difference. Since her other sister seemed all right with living at Gum Moon, she was left there. Glenn’s senior aunt, however, did make it a point to pick her youngest sister up every Friday evening so that she could be with the rest of her family on weekends.

Meanwhile, Glenn’s grandfather paid a matchmaker in China to find a replacement wife who would come to San Francisco to help care for his children. He stipulated that the woman should be older and neither any longer capable of bearing children or having any young children of her own. The match was made sight unseen, and the woman traveled to San Francisco as a paper daughter. She was to marry Glenn’s grandfather once she cleared through the immigration process at Angel Island.

There were two problems, however. The first was that Glenn’s grandfather’s prospective new wife turned out to be a far younger woman than was expected. The second problem was that she somehow could not keep the information that she had studied for the immigration interrogation straight. She was detained on Angel Island for about a year. As Glenn’s grandfather still had nobody to help with his children, Glenn’s youngest aunt stayed at Gum Moon.

Glenn’s grandfather quickly married his paid-for bride once she got free of Angel Island. She soon became pregnant, and the arrival of her first American-born child was followed by four more. Some ten years after her stepmother’s arrival in San Francisco, Glenn’s grandfather asked the aunt who was still living at Gum Moon and twelve years old by then if she wanted to return home. Her eldest siblings were married, and several others, Glenn’s mother among them, were old enough to care for themselves. There were, of course, three young stepsisters and two even younger stepbrothers to consider. Glenn’s aunt figured that she would wind up having to care for them and decided that Gum Moon was a far better option. She stayed at her “home” away from home until she graduated from high school and found a job as a secretary for a company located in downtown San Francisco.

FULL INCLUSION AS A FAMILY MEMBER

“I Really Enjoyed Those Times”

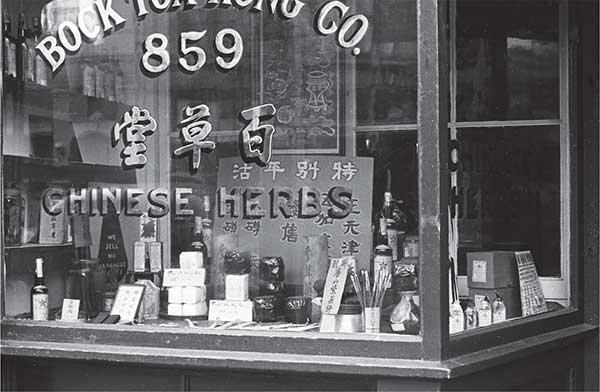

One of the more interesting things that happened to me as a Leong was when I had a bad case of gastrointestinal discomfort while visiting the family. I was very uncomfortable, and there was no way I could hide it. Everyone was concerned, and when I explained that I had been feeling badly for several days, Mr. Leong told me to get my coat on, because he was going to take me to get something for my problem. We rode the bus all the way into Chinatown from the Richmond District, and we wound up in a dingy and pungent-smelling little storefront place that was an herbalist shop. After the bus ride and the walk from the bus stop to the shop, I was feeling a little worse than even before, so I don’t remember much of what happened. Mr. Leong said a whole lot of things in Chinese while pointing at me. The old Chinese guy behind a counter filled with odd-looking things looked at me and nodded a lot. He then hustled around pretty quickly to pull stuff out of this drawer or that one or out of one cabinet or another and finally had a pile of what looked like dust, dirt, twigs and bark on a square of paper. He spoke more Chinese with Mr. Leong, wrapped everything up into a little bundle and out we went. Back at the house, Mr. Leong had me sit to rest while he boiled up the mix from the herbalist. It neither smelled good or bad, but it certainly had a distinctive odor. Glenn finally came in with a teacup and told me to drink it all down. I looked at it with some doubt, and Glenn stepped a few steps back and repeated that I had to hurry up and chug it. I did. It wasn’t long before I was feeling better. Except for not feeling well, it was really a fun and exotic adventure for me.

The Leongs went out for dinner a lot, and Glenn and I often went with them on weekends. I really enjoyed those times, because Glenn’s father, who was the family head and in charge of ordering, always selected authentic dishes. Most Chinese dishes were authentic to me because I had never had any of them before. Mr. Leong never picked anything off the menu just for me, and that made me feel like I was fully included into the family. It even made me feel a bit Chinese. Conversation became easier, too. The Leongs spoke in a blend of only Chinese, Chinese and English within a single sentence and English only. They spoke English to me, of course, but the way they were so quickly and naturally able to switch words and phrases back and forth made me feel that I was always fully engaged in whatever discussion we were having.

The greatest moments of acceptance for me were my graduation from medical school and the red egg and ginger party that the Leongs gave for our daughter Amy. Glenn explained that the red egg and ginger party was something that every Chinese family would have done and that it was not just for Amy or for me per se. I understood that, but the underlying sensation that I had through it all was that I was being acknowledged and acceptance was being conferred on me for providing the family with a daughter. The party was filled with lots of talking, laughing, smiling and even some hugging, so the celebration was really very special to me.

I did not go to medical school in California, so when Mr. and Mrs. Leong and Glenn’s aunt who had lived at Gum Moon and her husband drove all the way from San Francisco to my graduation, I was extremely flattered. By that time, Mr. Leong, who suffered from weak lungs and heart problems, was not walking much and had to use oxygen. He was not in too much distress, but it really moved me that he as well as the others would make the effort to see me graduate. For me, it was a final acknowledgement and a proof of my worthiness to them as a full daughter. After the graduation ceremony, we went to one of the local Chinese restaurants for a celebratory meal. The menu had Chinese as well as English on it, and Mr. Leong, in his usual role, did the ordering. It was an enjoyable meal. Walking out, Mrs. Leong said that she thought the food was good but not quite as good as it would have been back in San Francisco’s Chinatown. I thought back to the episode with my dim sum and smiled.

Doctor’s office, clinic and pharmacy, all in one spot. Ken Cathcart Collection. Courtesy of Schein and Schein.

CHERYL’S SPOUSE, IN-LAWS AND NEW FRIENDS

“To Me, They Were Just Like Anyone Else”

Cheryl is in her early sixties.109 She grew up in East Oakland in a mixed neighborhood of whites, blacks and Latinos. There were no Asian families nearby, however. Although they were well aware of Oakland’s Chinatown, Cheryl and her family never saw a need to go there. It would not be until she was in her mid-twenties that she would meet her former husband. He was born in 1956 at Chinese Hospital, and Cheryl was born at Stanford a year later. Cheryl remembered:

I was working in San Francisco as a legal secretary, but I lived in Oakland. I liked shopping in San Francisco’s downtown partly because it was so close to where I worked. I met my ex-husband in Macy’s on Geary Street. He was a sales assistant in the bedding department, and I was looking for some bedding. Neither of us was dating anyone at that time, and we hit it off and began to go out. He was full Chinese, but that had nothing to do with why I was attracted to him or liked him or eventually married him. I didn’t see him as unique or extraordinary because he was Chinese. In fact, he eventually introduced me to several of his coworkers who were also Chinese Americans. After more than thirty years, I am still friends with one of them because we were both legal secretaries and runners and we would often meet to go running and train for races. We talked about everything and anything, but it was the usual girlfriend-type things. Our different ethnic backgrounds were of no consequence at all.

Clearly, after I met and became involved with my ex-husband’s family, I saw or was introduced to things that were Chinese. They often had authentic family-style Chinese food, which I had really never had before. There were frequent Sunday night dinners at their home that were prepared from ingredients that my mother-in-law and father-in-law acquired in Chinatown. There is very little of it that I didn’t like. Well, there were a few things like chicken feet that I just couldn’t get into. My brother-in-law would taunt me at restaurants with them. He also delighted in teasing me with sea cucumbers, which I once made the mistake of asking him about. Oh, a whole steamed fish with head and eyes all in place was sort of gross to me, too. I was quite taken by my father-in-law insisting on eating just the head and tail because he wanted the rest of the family to enjoy the best parts of the fish. My husband’s parents spoke Chinese to each other a lot at family dinners, and I had no idea what was being said. Very often, I would ask my husband, but his Chinese had gotten so bad that he could only pick up an occasional word or two. It left me pretty frustrated. The house had a lot of Chinese furnishings and artwork in it, but I never looked at any of it as “foreign” or “Chinese.” To me, they were just like anyone else that I knew and liked.

CHINESE ART AND HISTORY

“I Was Really Fascinated by Everything He Told and Showed Me”

From very early on, Cheryl found her father-in-law to be a very interesting person. He had only gone through the equivalent of two years of high school before arriving in San Francisco from China at the age of seventeen prior to the start of World War II. He spoke English with a Chinese accent, but that never bothered Cheryl. She remembered:

Sidewalk shoppers on Stockton Street, with one of the four Ping Yuen housing projects in the background. Photo by author.

Jade belt fastener in the likeness of a mother dragon with her baby. Photo by author.

I became interested in Chinese history and culture because of my father-in law. He was a very kind person, and I always felt comfortable with him. He liked to show me the artwork that he had in the house. He especially loved to talk about jade. He would show me how a good piece of jade was translucent, and if you looked closely, it would have tiny crystals throughout it. He would explain how his jade art pieces were made and what they were originally used for or what they symbolized. He did the same thing with the many ivory pieces that he had as well. My brother-in-law once asked me if his dad was boring me. I told him, “No.” I was really fascinated by everything he told and showed me.

My father-in-law loved to show me pictures from his many art books. He would talk for hours about a painting, for example. I learned so much about artists, styles of painting or calligraphy and the different Chinese dynasties and historical periods. I think the one thing that captured my attention and imagination about all these things was the sincere and loving way in which they were told to me. Over the years, I think that I have forgotten a lot about these things, but I will never forget the openness and fondness that my father-in-law showed to me through his talks about Chinese art and history.

I went to Chinatown and Clement Street regularly with my in-laws for shopping trips. It surprised me at first how they would be very careful about what store they went to for certain things. There was always the “best place for produce” or the “only decent shop for chicken” or such-and-such a bakery for certain types of dim sum. It seemed like a lot of trouble to me, but I gradually got used to it. It seemed more fun or more of an adventure than going to Safeway for one-stop shopping. I learned to appreciate that different places did have different quality things; even if they were the same sort of things. Now I shop that way as well. I have my favorite spots for each of the things I need. I will only go to a supermarket for paper goods or cleaning supplies.

SOME VERY SPECIAL MEMORIES

“You Have Always Been Like a Daughter to Me”

I got along well with both of my in-laws, but after my father-in-law passed away in 1981, things really changed between my mother-in-law and me. She became much more open than ever before. She was even very willing to share personal or intimate things with me. I thought that she had become lonely without her husband and with all of her children grown and out on their own. Our relationship was a very positive one, and instead of being my mother-in-law, she started acting like a friend. I felt badly for her, of course, that she had lost her husband, and it felt really good to grow closer to her. I missed my father-in-law terribly as well, so I felt that I understood how she must have been feeling.

We would go out shopping or out to lunch, and I always felt as if I were with one of my younger girlfriends. We talked and laughed a lot about silly things. She would stop by my office and surprise me with dim sum from Chinatown and just to say hello. She would often say that she was just out taking bus rides and shopping in Chinatown or at her favorite downtown store, the Emporium. Not long before she suffered a stroke, she called me to say that she was downtown and lost. She was trying to find my office to visit me but couldn’t remember the address or the building. She had been to See’s to buy me some candy and she wanted to stop by, but she was confused. I was extremely busy at work, but I talked to her and got her to describe where she was so I could go find her. I was able to locate her pretty quickly, and she calmed down and told me how much she appreciated what I had just done. I walked her to the nearest stop for the 38 Geary and watched her get on the bus that would take her home. I called her before leaving work late that afternoon and was relieved that she had made it and seemed to sound all right.

I had been divorced from her son for quite a while when this happened, but I felt that I should call him about it. He made sure that she got a medical evaluation, and over time, he would contact me to keep me updated about her medical progress.

Cheryl continued to visit her former mother-in-law at her now-empty home in the Richmond District. She would drive over either after work or on weekends several times a month. Cheryl enjoyed it that the two of them continued to maintain an especially special bond. Cheryl laughed as she recalled a time when they had gone out of state by car to visit her former brother-in-law and his family:

It was before the divorce, and my ex-husband, my mother-in-law and I were driving from our home in New Jersey to visit my then brother-in-law and his family in South Carolina. It was winter, and there was a storm, and we were driving at night. Snow was blowing, the road was slick and everyone was driving really slowly. My ex was asleep in the back seat and my mother-in-law had never learned to drive, so I had been behind the wheel for a long time, and we were on the interstate, so there was nowhere to stop. Whenever she got nervous, which was a lot, my mother-in-law would snack on things like cookies, candy, chips or some of those yucky dried and salty Chinese things I couldn’t ever get used to. That night, she was eating Cheese Puffs because being in a car in the snow at night was not something that she had ever really experienced before. She asked me if I were nervous while driving, and I told her that I was. She told me to take some Cheese Puffs, but I told her that I couldn’t. I had to keep my eyes on the road and I needed both hands for driving. She asked me that if I wanted, she could feed me. At first I said “No,” but the low visibility, my tiredness and the sound of her rattling bag and crunching Cheese Puffs made me change my mind. So there I was with my entire body stiff and nervous trying to steer us through darkness, snow and ice while eating Cheese Puffs being hand-fed to me by my Chinese mother-in-law.

Cheryl sometimes found the friendship with her mother-in-law burdensome after her father-in-law’s passing. She felt that the older woman might have been developing a dependence on her. Her word for it was “clingy.” Nonetheless, their friendship never wavered.

I was up at her house not long before my mother-in-law became seriously ill, and she took me upstairs to her bedroom. She went over to her jewelry box and came back with two jade bracelets that I had never seen before. They were the ring type that so many Chinese women wear on their wrists. One was plain, but the other was very beautifully adorned with finely worked gold bands. I would never claim to be a jade expert, but my fatherin-law’s past talks had provided me with a good eye for it. These, I knew, were very fine pieces. Coming from a much older Chinese woman, I also appreciated that they were very special. My mother-in-law handed them to me and told me that she wanted me to have them. I was stunned and was hesitant to accept them. She pushed them into my hands and said, “Yes. I want you to take them because you have always been like a daughter to me. Take them.” That made me get all teary.

Cheryl has since remarried and lives in the Berkeley Hills with her husband. The couple has also reconnected with her former brother-in-law and his wife, Frances. Cheryl no longer jogs because of what she calls “bum knees.” She and her husband enjoy golf, bird watching and travel. Cheryl admits that, sometimes, when she happens to look across the Bay at night, she can’t help but think of how she once was “almost Chinese.”